Ejection of Blood

The pumping action of the heart results primarily from ventricular contraction. The atria act more as collecting reservoirs, and their

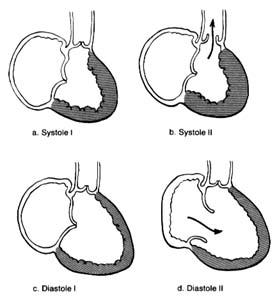

Figure 10. A ventricle during two stages of systole and two stages of diastole.

contraction accounts for only a small part of the blood entering the ventricles from the atria; most of it is sucked in by the ventricles. Since the state of contraction or relaxation of the ventricles determines the overall volume of the heart, it is customary to divide the cardiac cycle into two periods: the period of ventricular contraction, or systole; and the period of ventricular relaxation, or diastole .

During systole the beginning of ventricular contraction and the resulting first rise in the pressure inside the two ventricular chambers causes the two atrioventricular valves to close (fig. 10a ). The sudden tensing of the atrioventricular valves produces a loud noise—the first heart sound. Now the pressure can effectively build within the ventricles as they contract, until it exceeds the pressure in the aorta and the pulmonary artery, at which point the two semilunar valves are forced open and blood begins to flow into the two arterial trunks (fig. 10b ). Blood is pumped with considerable force and velocity during the first half of the ejection, and then gradually slows down. At the moment ventricular contraction ends and the period of relaxation begins (diastole), pressure in the cavities starts to fall, causing the semilunar valves to be sucked into

closed position (fig. 10c ). Closure of the semilunar valves produces the second heart sound. Relaxation of the ventricular muscle now produces a rapid fall in pressure in the two ventricular cavities, and the moment ventricular pressures fall below atrial pressures the two atrioventricular valves open widely, permitting the ventricle to fill with blood from the atria (fig. 10d ). As stated, relaxation enlarges the ventricular cavities and sucks in atrial blood; this occurs mostly during the first third of the diastole; during the middle third relatively little pressure change and flow occur. This is the period of rest, diastasis . The final third of the diastole involves the contraction of the atria, at which time the small remainder of blood (20 percent of the total volume or less) enters the ventricle from the atria. From the above description two points are clear: (1) During both systole and diastole there are short periods of time during which flow of blood ceases; these occur between the time one set of valves closes and the other opens, as shown in figures 10a and 10c . These two periods are referred to as isometric contraction and relaxation of the cardiac muscle; they are important in permitting efficient and rapid rise and fall in pressure. (2) Flow through the two sets of orifices does not occur with uniform volume and velocity; maximum flow occurs during the earliest part of ventricular ejection and ventricular filling.