2. Some Modes of Excelling

Let us step away from the vertiginous chasms of speculation about historical causation and turn our attention back to Paris in the Age of Revolution and to the lives and work of some of the most accomplished people of that place and time. To examine these models of excellence biographically and taxonomically, that is, in the context of the separate evolutions of their respective arts, has been the purpose of the first half of this study. To examine their modes of excelling situationally, in the context of the general social and cultural characteristics of Paris in the Age of Revolution, will be the purpose of the second half. Such an examination may reveal the outlines of an unplanned, underground community.

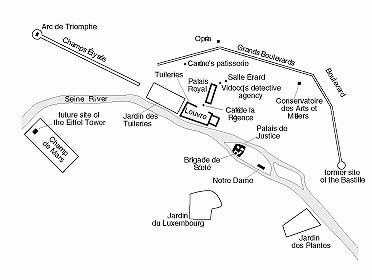

Public spaces of Paris in the Age of Revolution

6. Mounting Spectacles

On his wedding day, Rameau’s nephew hired all of the players in Paris of the hurdy-gurdy, a quasi-automatic stringed instrument then in fashion, to accompany him and his bride through the streets of the capital. He did this in spite of his poverty and his repeated claims that the only reason human beings did anything was to put food in their mouths.[1]

Rameau’s nephew’s wedding anticipated the French Revolution, when this anonymous ditty appeared and gained immediate popularity:

Il ne fallait au fier Romain,

Que des spectacles et du pain;

Mais au Français plus que Romain,

Le spectacle suffit sans pain.

The proud Roman used to require,Clearly the experience of food shortages during the Revolution only partly explains the quatrain; one must also take into account an extraordinary profusion of public spectacles, a profusion that continued after the Revolution ended.

Nothing but spectacles and bread;

But the Frenchman beats the Roman,

Living on spectacles without bread.[2]

Three interrelated historical trends contributed to this development. First, over the course of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, many formerly private activities took place increasingly often in public locations and in front of audiences. Second, after their activities had become public or while making them public, people in a wide variety of occupations began to attract and appeal to audiences by emphasizing those aspects of their activities immediately striking to the eye or ear; in short, their activities took on the character of spectacles. Third, the publishing industry grew extremely rapidly after 1789, and the publication of ever more advertisements, reviews, and descriptions of public spectacles accelerated the growth of the latter in turn. The whole world seemed to be mounting spectacles.

| • | • | • |

“The publicization of social life” is how one might summarize in a phrase a manifold and variegated but unidirectional change undergone by French society and culture in the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries. “Publicization” was the process of the private becoming public, just as “privatization” is the process of the public becoming private. Privatization may refer to people’s either ceasing to participate in certain activities, withdrawing from the social and political in favor of the individual, or continuing to do the same activities but transferring them to a setting away from general scrutiny. The Western world has experienced both kinds of privatization in the late twentieth century. In the United States, fewer and fewer people have voted in elections, a form of withdrawal from public life. In France and other countries of Western Europe, certain economic activities have been transferred from the government—back—into private hands. But the eighteenth century was an age of publicization. Activities that had formerly been restricted to only a few people or to widely dispersed people, who had conducted them in their own residences or in other places with severely limited access, were opened up to or taken up by large numbers of people and conducted in concentrated groups meeting in nonresidential sites, sites of relatively free access and often established for the specific purpose of carrying on one particular activity.

In the United States, Alexis de Tocqueville is best known for De la démocratie en Amerique, but in France he is equally well known for L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution. In the latter book he shows that in some important ways the French Revolution did not break with the past as decisively as the revolutionaries and most observers, whether friendly or hostile, believed it did. For example, the centralization of power, so brutally completed by Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety, had actually been underway for centuries and “the Revolution consummated suddenly…what would have been consummated gradually, by itself, in the long run.” [3] Likewise, in its advancement of the publicization of social life the Revolution only accelerated an already well-established trend.

The Revolution abolished privilege—privus lex, or private law—and created a republic—a res publica, or public thing. It replaced a system based on the special political and legal prerogatives of a few people acting apart with a system based on the political will and legal equality of masses of people acting in common. In Les Origines intellectuelles de la révolution française, Daniel Mornet contends that a spirit of debate and criticism gradually permeated the educated classes of French society during the eighteenth century and that this permeation was one of the causes of the Revolution. At the same time, the arena of argument gradually expanded. An ever greater number of people began discussing an ever greater variety of social concerns, concerns that formerly they had either not had or not expressed, but had relinquished to the king and his ministers. Mornet also found cafés in Paris, academies in the provinces, and public lecture series, literary societies, libraries, Masonic lodges, and newspapers throughout France proliferating in large numbers during the eighteenth century. The French were respiring the increasingly charged atmosphere of critical discourse in these increasingly numerous and, to varying degrees, public places. The progress of the spirit of debate was taking place in tandem with the progress of publicization. Meanwhile, power remained concentrated in the private hands of the king. But in 1789 King Louis XVI suddenly and unwittingly gave political form and impetus to the intellectual movement by convoking the Estates General, a three-tiered assembly that had not met for 175 years and that consisted of elected representatives of every social class. The French Revolution, writes Mornet, was one “in which if not the majority, at least a very large minority, more or less enlightened, discerned the faults of a political regime, articulated the profound reforms it wanted, and then converted public opinion little by little and acceded to power more or less legally.” [4] Mornet may or may not convincingly demonstrate a causal connection between the general diffusion of critical discourse in France and the outbreak of the French Revolution, but he does demonstrate the publicization of that discourse during the eighteenth century, and the publicization of political power after 1789 is incontestable.[5]

Economic activity also underwent publicization during the eighteenth century. The Bourse, the Paris stock exchange, was founded in 1724. Even large business ventures had formerly been undertaken by an individual or at most a few capitalists, but in the eighteenth century they began to be financed through shares sold to the public. And these transactions were assigned to a fixed public site in, successively, an old palace, a church, the Palais-Royal, and finally today’s Bourse, a building erected in the early nineteenth century for just this purpose. According to the economic historian Ernest Labrousse, “from 1750, and particularly from 1780, joint-stock companies spread, into coal mining, metallurgy, spinning, banking, and maritime insurance. The Journal de Paris and the Gazette de France published the quotations.” [6]

The French Revolution accelerated the publicization of economic activity by abolishing craft guilds, licensed monopolies, and internal tariffs. The Old Regime’s guild system had privileged the craft masters, who ruled all the workers in the craft—that is, regulated their apprenticeship, admission, and promotion, their practice of the craft—and also maintained their exclusive right to practice the craft. The Old Regime’s system of licensed monopolies had given the holders of monopoly patents, or privilèges, the exclusive right to engage in certain activities in certain places; for example, the Académie Royale de Musique, generally referred to as the Opéra, had the exclusive right to give public performances of music in Paris. The Old Regime’s system of internal tariffs had privileged local producers of goods. The revolutionaries’ abolition of these three systems of economic regulations opened a whole range of craft, business, performance, publication, and market opportunities to a broad public.

Paris was becoming a public city in the eighteenth century. Several of its largest outdoor open spaces took shape then. The Champs Elysées was extended and lined with trees in the 1710s and again in the 1770s. The Champ de Mars, first a military parade ground, later also used for civilian gatherings, was laid out, and the Jardin du Roi, the royal botanical garden, later renamed the Jardin des Plantes, was doubled in size, both around mid-century. The Jardin du Luxembourg was expanded by the revolutionaries and then expanded again by Napoleon. Both the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Jardin des Tuileries, which had been opened to the public in the late seventeenth century, were enclosed in walls until the early nineteenth century, when Napoleon ordered the walls demolished and replaced with less-forbidding grillwork.

The Jardin des Tuileries adjoins the Louvre, which may be taken to exemplify the process of publicization in indoor spaces. The Louvre—including the wing called the Tuileries, originally a separate palace, then connected to the Louvre, finally destroyed—was built over the course of several centuries by a succession of kings for their own use. During the eighteenth century, Kings Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Louis XVI allocated a series of rooms in it to the Académie Royale de Peinture et Sculpture for artists’ quarters and for the biennial Salon, the academy’s exhibition of new works. Finally, at the end of the eighteenth century the revolutionaries converted it into a permanent public art museum.[7]

Indoor public spaces, both those conceived in physical terms, such as exhibition and performance halls and cafés and restaurants, and those conceived in social terms, such as concert and lecture series and clubs and societies, proliferated all over France at an increasing rate as the eighteenth century progressed. Mornet found both literary societies and public libraries already existing in the provinces in the first half of the century. However, “after 1760, and particularly after 1770, it’s as if there is a contagion of societies” and “it’s particularly after 1770 that the number of these libraries multiplies.” [8]

Slowly during the first three-quarters of the eighteenth century and then more rapidly in the last quarter of the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century, Paris was becoming the great public entertainment capital that it still is today. In the first of these two seventy-five-year periods, large numbers of people gathered for diversion on three Paris fairgrounds, those of the Saint-Laurent Fair, which ran all summer long, and the Saint-Ovide Fair, which ran from mid-August to mid-September, on the Right Bank; and on the Left Bank the Saint-Germain Fair, one of the great fairs of Europe, which ran during February and March. The fairs offered a variety of inexpensive foods to taste and a variety of inexpensive shows to see. They fell victim to their own success, for after midcentury a sort of permanent fair grew up along the Boulevard du Temple, where one could get lemonade, coffee, or wine, see a multiplicity of games of skill, wax figures, strong men, trained animals, and demonstrations of popular science all year round, and in comfortable and attractive cafés and halls, not just temporary stands. The attractions of the Boulevard du Temple gradually extended into the Boulevard Saint-Martin and eventually became the core of the lengthy public promenade known as the Grands Boulevards. In the 1780s the rebuilding of the Palais-Royal led to the creation of another permanent fair in and around that old palace, its long wings housing cafés, pastry shops, bookstores, little performance halls and exhibition spaces, and its large courtyard serving as the meeting place for the transaction of speedier or shadier business. The heyday of the Boule-vard du Temple as a center of public entertainment lasted longer than the heyday of the Palais-Royal, which was confined to, and therefore more distinctive of, the Age of Revolution.[9]

A dramatic manifestation of the process of publicization was the spectacular burgeoning of theater. In the eighteenth century, three institutions, the Comédie-Française, the Comédie-Italienne, and the Opéra, had a legal monopoly on the professional performance of plays in Paris. Other professional groups, which gave their performances first at the fairs, then after mid-century in newly erected permanent theaters on the Boulevard du Temple, and finally toward the end of the century in the Palais-Royal, avoided the prohibition against them in various ways. Some paid the Opéra to extend its privilège to them for a specific number of years. Others exploited loopholes in the wording of the privilège, presenting plays with marionettes, child actors, or silent adult actors holding up placards containing their lines. Still others simply ignored the law and, thanks to tolerant authorities such as Lieutenant-General Sartine, the same police chief who allowed the publication of the Encyclopédie, for a while did it with impunity. In the 1760s, just as competition from the unprivileged theaters began to intensify, attendance at the Comédie-Française, one of the privileged theaters, began to set records. In early 1791 the revolutionaries abolished the system of privileges, and the number of professional theaters in Paris jumped from fifteen to thirty-five within the year. All together at least forty-five new theatres opened during the Revolution, although many closed after a short time. Amateur theater likewise expanded during the second half of the eighteenth century, spreading from the royal court to the aristocracy to the bourgeoisie to the working classes. By the end of the century, wrote a chronicler of the Paris stage, “people were acting in wine bars, in cafés, in basements, in attics, in stables, in sheds,” and amateur theatrical groups in the capital numbered more than two hundred.[10]

During the eighteenth century the population of Paris hardly grew at all, remaining between about 525,000 and 550,000. During the first half of the nineteenth century the population of Paris more than doubled, from about 550,000 in 1801 to about 1,300,000 in 1851. Seeing these demographic figures makes one think of the conventional population bomb, but learning about the multiplication of Paris’s theaters, or the octupling of its public reading rooms from 23 in 1819 to 198 in 1845, or the vigintupling of its public bathtubs from 200 in 1789 to 500 in 1816 to more than 4,000 in 1839, compels one to imagine a publicization explosion of socio-nuclear power.[11]

Virtuosity developed in these public spaces, both physical and social, that were so rapidly propagating. Chess emerged from private residences into the cafés of Paris, the first of which opened in the 1670s; by 1723 there were around 380 of them; by 1788 around 1,800; by 1807 around 4,000. Late in his life, Philidor mentioned that when he had first started playing chess in Paris cafés the game was played in a great many of them, which suggests that the momentum of its publicization may have helped to propel his own increasing interest in it.[12] With regard to virtuosity in chess, we have already observed the central role of one of the first Paris cafés, the Café de la Place du Palais-Royal, later known as the Café de la Régence.

After the outbreak of the French Revolution, restaurants and pastry shops began to reproduce as fast as or faster than cafés. The number of restaurants in Paris quintupled between 1789 and 1803, from a total of approximately one hundred to approximately five hundred, and more than quintupled again between 1803 and 1820, by which time the total had reached nearly three thousand. As for patisseries, Carême says that before the Revolution there were few, although he gives no figure, in contrast to the 258 of them in business in 1815.[13] Few historical developments are clearer than the publicization of dining during the Revolution. Whereas the aristocrats had dined in one another’s homes, the revolutionaries dined in cafés, taverns, and restaurants, and the cooks of the former became the cooks of the latter. Thus, politics carried cuisine along with it in its migration from the private to the public sphere. This development exerted a strong influence on Carême’s early career, providing him with employment opportunities in a tavern, a restaurant, Bailly’s well-known patisserie just north of the Palais-Royal, and Gendron’s equally well-known patisserie inside that public entertainment cynosure.

Before the Revolution the Opéra had a double privilège—in theater, in which it shared its public performance monopoly with two other institutions, and in music, in which its monopoly was total, at least legally. For just as rival groups of thespians found ways of circumventing the prohibition against them, so too did rival groups of musicians. Like the directors of some other theaters, those of the Opéra-Comique, where Philidor’s music first won recognition, simply paid a tribute to the Opéra. The older half-brother of Philidor who founded two early public concert series in Paris, the Concerts Spirituels and the Concerts Français, did likewise. Presenting concerts every year from its inception in 1725 until 1790, the Concerts Spirituels turned out to be the most successful series of the eighteenth century. A fugue of public concert series developed from the Opéra’s privilège in the 1770s and 1780s when music lovers organized themselves into nominally private “concert societies” to which they paid annual membership dues. Such was the origin of, for example, the Concerts des Amateurs (Music-Lovers’ Concerts), the Concerts des Amis (Friends’ Concerts), and the Concerts de la Loge Olympique (Olympic Lodge Concerts). This last series, as its name suggests, was staged by a Masonic lodge, and shows the sometimes quasi-public character of Freemasonry, for attendance at the concerts was not restricted to Masons.[14] Freemasons debated social and political issues at their meetings, and a prominent school of Revolution historiography considers these meetings precursors of the meetings of the political clubs and elective assemblies of the first French Republic.[15] Even in fields as dissimilar as music and politics, the vector of publicization was sometimes the same. Masonic lodges in Paris reproduced from half a dozen in the 1730s to 170 in 1771, remaining at about that number until the Revolution brought about their replacement by other social spaces.[16]

The advent of a public space in Europe for music, the public concert, enabled Paganini to make the leap from court attendant, his position in Lucca at the beginning of his career, to touring virtuoso, his role when he appeared on stage after stage throughout Italy and, eventually, in Austria, Bohemia, Poland, Germany, France, and Great Britain as well. In Paris he ultimately had his own public concert space, briefly, in the short-lived Casino Paganini. Liszt, born three decades later, appeared frequently in public right from the beginning of his career. The number of concert venues in Paris had multiplied so much by Liszt’s time that at least two of them, the Salle Érard and the Salle Pleyel, could specialize in piano music, becoming crucibles of keyboard skill.

A variety of small theaters and halls devoted to what are usually categorized as entertainments rather than fine arts also materialized in Paris during the Age of Revolution. Intricate automata and seamless illusions were contrived for the amusement of eighteenth-century princely courts, but the golden age of stage magic had as its setting first rented exhibition halls and then performer-designed and -owned theaters for the public, such as the Théâtre des Jeunes-Acteurs of Comte, the Palais des Prestiges of Phi-lippe, and the Théâtre Robert-Houdin.

In many cases, the publicization of an activity encouraged a separation of people into performers and spectators or, where that separation already existed, encouraged a widening of it.[17] For example, when chess was taken from private residences into cafés, the best players gradually attracted other café-goers around their tables, turning the players into performers and the others into spectators. In contrast to chess, music had a long history of being played in front of an audience. Still, the distance between the musician and his audience increased with the migration of concerts from aristocratic salons to concert halls: The musician climbed onto a stage; the occasion rigidified into a formally structured event; the audience lapsed into passivity.

On the one hand, the publicization of political and economic life, culminating in the Revolution, favored the elimination of privileges and con-sequently the amalgamation of privileged and unprivileged people into a single group. On the other hand, publicization also favored the separation of people into performers and spectators, two distinct groups. And the performers, at least the most successful among them, eventually acquired a disproportionate share of wealth and power and thus became a new privileged elite. But neither wealth nor power was the basis of the privileges of the new elite’s membership. Rather their wealth, like the wealth of the new society’s entrepreneurs, and their power, like the power of the new society’s politicians, derived from their ability to please the public.

| • | • | • |

During the publicization process, in a wide variety of human activities, groups of spectators formed and swelled and separated from actors, while, reciprocally, the latter made their activities more distinctive in order to try to attract and appeal to the new, larger, and more distant audiences. Actors in the nontheatrical sense became actors in the theatrical sense, indeed actors of a particular kind of theatricality. They gave their activities éclat—brilliance, flash, fanfare, zip, flamboyance—that is, they turned their activities into spectacles.

The Revolution was a gigantic spectacle. Its principal events consisted in large part of crowds of people coming together in public, whether to demonstrate for political and economic goals in the streets, to debate and enact legislation in the new representative assemblies, to celebrate and forge national unity in parks and gardens, to drill and fight as soldiers and national guardsmen in fields, or to witness executions in town squares.

Particularly characteristic of the Revolution were its fêtes, celebratory gatherings organized by the government with programs of parades, music, speeches, banquets, dedications of monuments, and other ceremonies that took place in the Grands Boulevards, the Jardin des Tuileries, the Champ de Mars, and other large public spaces of Paris, as well as in provincial cities and towns. Assemblies of one hundred thousand or more people were not uncommon at the Paris fêtes. In La Fête révolutionnaire, 1789–1799, Mona Ozouf argues that, in spite of the variety of their occasions, a funeral, an anniversary, a military victory, or religious worship, these fêtes had a certain unity of design—the enactment of a vision of utopia—and that this design was also that of the Revolution itself.

Ozouf acknowledges her indebtedness to Jules Michelet, the great nineteenth-century nationalist historian of the Revolution, who believed, as she puts it, in the “consubstantiality of the fête with the Revolution.” But Michelet, she observes, rather than focusing on the official government celebrations, assimilated a variety of different kinds of public gatherings, especially spontaneous formations of activist crowds, into the meaning of the word “fête.” In Michelet’s view, as the Revolution unraveled, veritable fêtes devolved into contrived fêtes, fêtes staged by the government that did not reflect popular feeling, however well attended they might have been.[18]

Michelet’s view of fêtes, in turn, was influenced by Rousseau, drum major of the Revolution, who wrote in his “Lettre à d’Alembert sur les spectacles” that “the only pure joy is public joy.” In the same work Rousseau expressed his disapproval of theater and his approval of programless outdoor fêtes in which large numbers of people participate: “Put the spectators into the spectacle; make them actors themselves; allow everyone to see oneself and love oneself in others, that all may be more closely united.” [19]

But as the Revolution proceeded, fewer and fewer public assemblies were spontaneous, and in fewer and fewer of them were the crowds real participants. Public activities were superseded by public spectacles.

Jacques-Louis David is best known today as the foremost French neoclassical painter, somewhat less well known as a leading revolutionary, and hardly known at all as a designer of fêtes. Although under the Old Regime he had been accepted into the exclusive Académie Royale de Peinture et Sculpture and been given a studio in the Louvre, he still felt stifled by the patronage system of the art establishment. He turned into an outspoken advocate of the publicization of art, arguing for open exhibitions of new works and open competitions for government commissions. With the advent of the Revolution he became not only the official image maker of such important events as “Le Serment du Jeu de paume” (The Oath of the Tennis-Court) and “Marat assassiné,” but also, as one historian has called him, the pageant-master of the republic. David designed the costumes, the plaster monuments, the stage sets, the parade vehicles, and other props for several of the most important government-sponsored fêtes of the early years of the Revolution. For example, when the revolutionaries decided to transfer Voltaire’s remains to a recently completed neoclassical church that they had rechristened the Panthéon, David conceived a Roman procession for the occasion, designing with motifs from antiquity a huge horse-drawn hearse, and outfitting its attendants with togas, lyres, spears, helmets, poles topped with eagles, even a few sedan chairs. As many as one hundred thousand people, not all of them in Roman attire, marched in the procession, and perhaps another one hundred thousand watched.[20] The route was clear: neoclassicism first as art of the privileged, then as public art, and finally as public spectacle.

The revolutionary spectacle par excellence was oratory. The representatives to the new assemblies ruling France had no experience or connections in government, were unknown to the public, and did not know each other. Those who acquired fame and power did it through successful public speaking, whether in the assemblies, in the streets, or in the political clubs. The speeches judged to have made the biggest impact were reproduced in summary or at length in the many newspapers that suddenly sprang up after the abolition of privilèges. These newspapers were expedited from Paris to all corners of France, and of Europe, where they were eagerly read. Oratory, like theater, became a mania. “Who isn’t an orator?” asked Sébastien Mercier. “Who doesn’t dream of being an orator, with this great and pleasant prospect?” [21] The quality of the oratory increased with practice and with increasing danger. Immediately before and during the Reign of Terror, what one said in public determined whether or not one stayed alive, encouraging prudence in choice of words. If one kept one’s head, one kept one’s head. Nevertheless, from the obscene, wildly gesticulating, unkempt and uncouth Hébert to the erect, wigged and powdered, self-controlled in manner if not in matter Robespierre, both of whom lost theirs, the Terror was one continuous fountain of crimson prose—and, of course, blood.

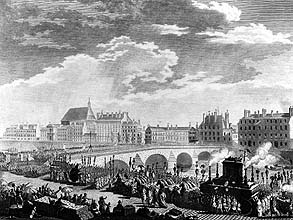

The guillotine repeated the same scene again and again, but never bored the audience. On a succession of increasingly spacious public squares in Paris, the Place de Grève, the Place du Carrousel, the Place de la Concorde, the Place du Trône, and in analogous locations around France, the whoosh, thwack, thud of the blade and head remained constant while the subsequent cheers of the increasingly large and more frequently assembled multitude grew wilder. Eighty thousand armed men lined the route between his prison and the Place de la Concorde when the deposed King Louis XVI made the short trip to his “shortening” in January 1793. After he was executed and the twenty thousand attending troops dispersed, there was jubilation and dancing around the scaffold.[22] Those who wanted to watch the enemies of the Revolution perish in greater numbers could travel to the borders of France, where a protracted series of wars against the monarchies of Europe began in 1792.

Figure 11. Two revolutionary spectacles. Spontaneous: Burning of the Pope in effigy at the Palais-Royal (top). Planned: Triumphal procession designed by Jacques-Louis David for the transfer of Voltaire’s remains (bottom). Author's collection. Photographs by J. Craig Sweat/Photographer.

Napoleon’s proclamation of the Empire in 1804 suspended public government, but not government-sponsored public spectacles. In fact, the Em-pire began with a grandiose neo-medieval ceremony in which Napoleon crowned himself emperor in the presence of the pope, a ceremony whose official representation was painted by Jacques-Louis David on a canvas thirty feet long and twenty feet high.[23] The fêtes of the Empire were predominantly military: reviews and parades featuring artillery, cavalry, and infantry in showy dress uniforms abundantly decorated with gold braid and embroidery and topped with bicorn hats, fur bonnets, Roman helmets, and shakos with tall plumes; presentations of crosses of the Légion d’Honneur and other medals; and distributions of neo-Roman regimental eagles, also the subject of an enormous painting by David, who had already used such eagles himself in Voltaire’s funeral procession.

The greatest spectacles of the Empire were not the fêtes of Paris and other French cities, however. They were instead Napoleon’s monumental battles, which had exotic locales for their theaters, which were the subject in France of exalted journalistic accounts and exalted pictorial representations, and which exhausted the Revolution’s spectacle of blood. As Napoleon himself said: “My power depends on my glory, and my glory on my victories. My power would fall if I did not sustain it with more glory and more victories.…A newly established government must dazzle and astonish. As soon as it stops throwing sparks, it falls.” [24] Thus, government became spectacular.

So did theater. Napoleon and his contemporaries loved theater but they adored spectacle. The emperor often attended performances of François-Joseph Talma, the foremost French tragedian of his day, engaged him in conversations about acting, and considered awarding him the cross of the Légion d’Honneur.[25] But it was Madame Saqui, the tightrope walker, whom he invited to participate in the celebrations of his name day, to entertain his soldiers in their camps, and to add variety to his military fêtes. He even summoned her to Vienna when he captured that capital. Her biographer writes:

After the collapse of the Empire, she bought a theater on the Boulevard du Temple, where her performances maintained their popularity for many years.[26]During that epoch of military glory, her great popularity increased even more when she thought of miming, on the tightrope, by herself, the battles and victories of the Empire.…Armed with a saber, she pretended to lead a furious charge whose momentum forced the imaginary enemy to retreat, or…stopping to shoot, she kneeled to fire, then fixed a bayonette on her rifle, and advanced irresistibly, or suddenly fell, as if she were wounded, flinging herself up again to plant on the pole a flag she carried wrapped around her waist.

Theater historian Marie-Antoinette Allevy summarizes the first half of the nineteenth century as “that era of French theater during which an extreme consideration was accorded, in every genre of drama, to the ‘spectacle.’” In that era, she argues, the mise-en-scène—the sets, props, costumes, lighting, and sound effects—gradually overwhelmed the literary aspects of drama—the dialogue, characters, and plot. “In the boulevard theaters, the division into acts disappeared in favor of the division into pictures [tableaux]. Ten, fifteen, twenty pictures succeeded one another in a single piece, each necessitating an appropriate decor.” It was the era of melodrama, of fantastic ruins, gothic palaces, pirate ships, nature at its wildest, the city at its rawest, of violence everywhere. “The technicians, the machinists, the decorators, the builders of props and sets exercised their imaginations to create new and original contrivances and devices: representations of the sea, of shipwrecks, drownings, fires, floods.” Like the actors, the technicians came out on stage at the end of the play to receive their applause, sometimes the loudest and longest ovations. The contemporary critic Théophile Gautier announced, “The era of purely ocular theater has arrived.” [27]

The fêtes of the Revolution contributed to this development. “We owe to Jacques-Louis David,” acknowledges Marian Hannah Winter, another theater historian, “usable scenery made to be climbed up, into and over to a degree not previously imagined. We also owe to him the marshaling and management of those hordes of extras who appeared in battle, ballroom, parade and harvest scenes, filing through the streets, squares and public gardens, and finally onto the stage itself.” Other spectacles also invaded the theater. In 1768 the Englishman Philip Astley “was the first to introduce acrobats, rope-dancers, and short mimed or dialogued scenes into what had been purely equestrian spectacles.” In 1782 he built on the Boulevard du Temple Paris’s first permanent circus—literally, “circle”; commonly, a mixed equestrian spectacle in a circular space. The Amphithéâtre Astley evolved into the Cirque Olympique in 1810 and began incorporating its feats of horsemanship and acrobatics into whole, connected stories, for example Murat, a dramatization of the life of Marshal Murat, the head of Napoleon’s cavalry. This subject allowed for the re-presentation in the heart of Paris of some of Napoleon’s most spectacular battles, the occasion of Gautier’s remark quoted above. Other boulevard theaters featured trained dogs, monkeys, lions, and tigers in their plays. Rope-dancers and mimes, led by Jean-Baptiste Deburau of the Théâtre des Funambules, expanded their vignettes into full-length dramas.[28] All this represented the French Revolution of the stage. Before the Revolution, in order to evade the restrictions imposed on them by the privileged theaters, the theaters of the fairs and the boulevards had cultivated these “lesser” theatrical arts, the arts du spectacle, as the French call them; after the Revolution abolished the system of privileges, the arts du spectacle began to take over theater proper.

Theater evolved into spectacle and/or spectacle invaded theater. Any way one looks at it, theater became spectacular. The same thing happened to painting, to science, to technology.

The incidents in the career of Jacques-Louis David that have already been mentioned indicate one way painting became spectacular. Another was through experimental kinetic picture shows, several with names ending in “-orama” (Greek for “sight”), which became extremely popular in the first half of the nineteenth century. A panorama had an outdoor scene painted on the wall of a rotunda, so that it encircled the spectators. Sometimes the spectators stood or sat in darkness and watched while lights played on the painting, animating a sunrise or a thunderstorm, or while actors used the painting as a three-dimensional backdrop. Sometimes the spectators walked around the rotunda, enhancing the three-dimensional appearance of a painting done in relief or with sculptural forms included. Louis Daguerre, before he invented photography in the late 1830s, created the Diorama, a series of large paintings on transparencies lit from behind. The transparencies were set in frames so that they could be lowered to and raised from the stage in sequence. One popular sequence depicted the eruption of Vesuvius. E. G. Robertson produced a much imitated magic lantern show called the Fantasmagorie. He entombed his theater in a disused Paris monastery where the ancient stone walls, musty smells, flickering candlelight, and the eerie strains of a glass harmonica reinforced the effect created by his projection of indistinct images, which he convinced his spectators were ghosts of their deceased relatives or of martyred revolutionaries such as Jean-Paul Marat.[29] But the revolution in this kind of spectacle did not take place until the end of the century, when the Lumière brothers invented cinematography.

The popularity and convincingness of Robertson’s Fantasmagorie owed as much to his reputation as a scientist as to his brilliant staging. For in his shows he not only raised specters but also gave demonstrations illustrating recent discoveries in acoustics, mechanics, and electricity. When Alessandro Volta, the inventor of the battery, came to Paris, Robertson be-friended him and helped him win recognition for his research on the nature of electricity by giving public lectures and expériences and a joint presentation before the Académie des Sciences, which awarded Volta a silver medal. The word expérience was ambiguous, meaning either “experiment, test,” the basis of science, or “experience, apprehension by the senses,” the basis of spectacle. Which were the expériences of Comus, who discharged electricity into gemstones and lodestones, sensitive plants and neurasthenic people, curiosity seekers and cadavers, and who presented his findings both in reputable scientific journals and in his hall on the Boulevard du Temple? Which were Franz Anton Mesmer’s expériences of “animal magnetism” that found so receptive an audience in Paris after the Viennese medical establishment had censured the inventor/discoverer of what became known, first, as mesmerism and later as hypnotism? And which were Georges Cuvier’s reconstruction of mastodons, pterodactyls, and saber-toothed tigers for museum display at the Jardin des Plantes? The popularity and convincingness of Cuvier’s public lectures, in which he predicted that comparative anatomists would soon be able to deduce the complete appearance and lifestyle of extinct animals from the discovery of a single bone, owed as much to his brilliant staging as to his reputation as a scientist.[30]

E. G. Robertson was also an early aeronaut who flew in both balloons and parachutes,[31] two late-eighteenth-century French inventions the tests of which often took place above large audiences in such public places as the Jardin des Tuileries and the Champ de Mars. But the main stage for technology was the industrial exposition, the nineteenth-century forerunner of the twentieth-century world’s fair. In France, the first Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie took place in a temporary building erected in the Champ de Mars in 1798. Ever larger and more lavish expositions took place in 1801 and 1802 in temporary buildings in the courtyard of the Louvre, in 1806 on the esplanade of the Hôtel des Invalides, in 1819, 1823, and 1827 in the Louvre itself, and beginning in 1834 at regular five-year intervals in various public spaces.[32] Technology’s successful siege of the Louvre meant its conquest of a status equal to that of fine art as a public spectacle. Everything converged in spectacle.

Virtuosity converged in spectacle. Mechanicians had built automata for scientific purposes, for sale to the wealthy, for the amusement of princes. Mechanicians had also built automata for spectacles in Paris, showing them in rented rooms, at the annual fairs, and in permanent exhibition halls on the Boulevard du Temple and in the Palais-Royal. Robert-Houdin presented several inventions at the exposition of 1839 and then his automaton Writer-Sketcher at the exposition of 1844, gaining a silver medal from the judges of applied science, attention from King Louis-Philippe, admiration from the public, and a sale to P. T. Barnum.

Music and technology converged in spectacle. Adolphe Sax also won a silver medal at the exposition of 1844, for his saxhorns, instruments resembling flügelhorns. But musicians resisted using them, so he went to the army to argue for their adoption in place of French horns and bassoons in marching bands. In 1845 the Champ de Mars was the scene of a battle between an army band of forty-five musicians and a band of thirty-eight assembled by Sax, an encounter witnessed by twenty thousand spectators. Sax won the audience’s applause and a military contract. At the exposition of 1849 he received both a gold medal and a medal of the Légion d’Honneur for his new invention, the saxophone.[33]

A public concert is inherently a kind of spectacle, so it is not always easy to determine where musicianship stops and showmanship begins. Paganini made his audience wait for him while he watched from the wings so as to be able to appear just when expectation had reached a peak. While he excoriated the tales of his pact with the devil, he also exploited them. The violinist Ole Bull told of Paganini coming on stage with his long black hair, a black swallow-tail coat, and a small box in his hand:

One of the few things outside of music that made an impression on Paganini was the magic show of Bosco. As for Liszt, according to Heinrich Heine, “no one in the world knows as perfectly as our Franz Liszt how to organize his successes, or rather how to stage them. In this art, he is a true genius, a Philadelphia, a Bosco, a [Robert-]Houdin.” Robert-Houdin described his own art as that of “an actor playing the role of a magician.” According to the newspaper Illustration:He then opened the box and took out a pair of spectacles, meditated a moment, apparently considering the next move, and finally, taking the bow in his right hand, and bending a little, put the spectacles on and looked about in a complacent manner. But how changed he was! The glasses were dark blue, giving a ghastly appearance to his emaciated face; they looked like two large holes in his countenance. Raising his foot and bringing it down promptly, he gave the signal to begin. It had been announced as his last concert in Paris for the season, and a true foreboding seemed to thrill through his listeners that they would not again see that lank, angular figure, with its haggard face, or hear again the wondrous witchery of his violin.

Paganini and Liszt were among the first musicians regularly to give concerts from memory, a common practice today. Their reviewers frequently mentioned it, although there is no inherent relationship between playing from memory and the quality of the playing. But it is always more impressive to see airialists perform without a net. In popularizing the performance of pieces whose chief interest for the audience consists of watching and hearing musicians meet the challenge of their technical difficulties, Paganini with his caprices and G-string solos and Liszt with his own and others’ piano études made perhaps their greatest impact on performance practices. Scheller and Clement and Dreyschock went to such extremes that they could be dismissed, and Mozart could renounce his own youthful excesses, but the showmanship of Paganini and Liszt was so integral to their musicianship and their musicianship was of so high a caliber that despite repeated efforts by some to purge it from the Western classical music performance tradition, and a virtually uninterrupted effort by others to deny its existence there, spectacle survives, even thrives.M. Liszt is not only a pianist, he is above all an actor.…Everything he plays is reflected on his face; one sees depicted in his physiognomy everything that his music expresses and even everything he thinks it expresses. He makes movements appropriate to each piece; he has postures, gestures, and glances for every phrase; he smiles at the graceful passages, and furrows his brow whenever he hits a diminished seventh. All of this is obviously lost for those of his listeners facing his back, so that it is out of a sense of justice and so as not to be unfair to anyone that he employs alternately two pianos facing in opposite directions.[34]

Neither chess nor cooking nor crime-detection is inherently spectacular. Philidor and the Café de la Régence masters made chess spectacular by playing several games at once without looking at any of the chessboards. They did not invent simultaneous blindfold play: Three-game demonstrations given by an Arab visiting Florence in the thirteenth century, by a Syracusan in the sixteenth century, and by an Italian in the early eighteenth century are mentioned in writings of their contemporaries.[35] What Philidor, Labourdonnais, and Kieseritzky did was to translate something eccentric into something central, to make an obscure achievement into a public spectacle and to establish it as a continuous tradition that has persisted for two centuries.

Carême made cooking spectacular by disregarding the old rule that whatever a chef sent to the dining table, with the exception of containers, should be food. He made his four-foot models of classical temples, Gothic towers, Indian pavilions, Chinese pagodas, and Turkish fountains not out of the pastry cook’s traditional pastillage (“paste”) of gum tragacanth, wa-ter, sugar, and powdered starch, which are all edible ingredients, but out of a mastic (cement or putty) of gum arabic, gum tragacanth, water, sugar, powdered starch, calcium carbonate, and marble shavings! “Finally, after having made several experiments in this matter, I succeeded in compounding this mastic, out of which I constructed, nine years ago, two large trophies, which are intact today, and still as splendid as they were on the first day.” [36] Carême’s inedible edifices formed the centerpiece of what amounted to a whole program for making a spectacle out of cooking, which included increasing the number and variety of dishes served in each course, piling up garnishes on top of large roasts and whole fish with the help of hâtelets, and commissioning serving implements with neoclassical ornamentation designed by himself. Carême made his preparations less to sate the stomach than to dilate the eye.

Vidocq, who as a youth had worked for the physicien Comus,[37] strove to make a spectacle out of crime-detection. He preferred to arrest suspects in a crowded tavern, bursting in suddenly with a group of Sûreté agents and shouting orders, than to apprehend them in a less risky but more isolated location. He liked to appear at Bicêtre for the ceremonial chaining of recent convicts at the start of their long march to the galleys, a semiannual event that drew as many as a hundred thousand spectators to this suburb of Paris for a day of edifying Schadenfreude, particularly piquant for Vidocq, since twice in his earlier life he had been among the participants, whom he now took the opportunity to berate publicly. In courtroom trials, Vidocq stole the show from the lawyers, using the witness box as a stage from which to recount his feats as a detective.[38] He finally got his chance to appear on a real stage at the age of seventy when he gave demonstrations of his disguises and other detective apparatus for two seasons at a London exhibition hall. But it was only with the creation of the detective story, out of Vidocq’s career and his account of it in his Mémoires, among other materials, that a largely private activity could be approximated to a spectacle.

The necessity or desirability of appealing to the public led to spectacularism in politics, theater, art, science, technology, automaton-building, musical performance, chess, cooking, crime-detection, and many other social activities. Spectacularism involved emphasizing those aspects of an activity that had intrinsic immediate eye- or ear-appeal or adding extrinsic features to an activity to give it that appeal. An institution specifically designed for appeals to the public—that is, for publicity—already existed. Not surprisingly, the prodigious progress of publicization and spectacularism was accompanied by a commensurate development of the press, a development that can only be described as spectacular.

| • | • | • |

Spectacles and publicity both involve making something public: the former, deeds; the latter, ideas. The French Revolution had a close association with publicity since its end was to make government public and since it came about in large part through the conquest of public opinion, through a publicity campaign. Signs of an important historical development lie in the evolution of the meaning of the word publicité from “the characteristic of that which is public” or “the act of bringing to public knowledge” in the eighteenth century to “the act or art of producing a psychological effect on the public for commercial purposes” in the first half of the nineteenth century. Equally significant is the evolution of publiciste from écrivain politique, or writer on political subjects, in the middle of the eighteenth century, to journaliste, or writer of articles on political and other public events, at the end of the eighteenth century, to agent de publicité, or advertiser of public events and commercial products, in the twentieth century. These two words were imported into English as “publicity” and “publicist” during the French Revolution.[39] The French publishing industry erupted in 1789, the beginning of the Revolution and also the beginning of a permanently increased outpouring of ephemera whose reports and advertisements of public spectacles increased the quantity of the latter in turn.

This intellectual debris has been measured. Only around 310 different pamphlets were published in France in the thirteen years between 1774 and 1786, while around 220 were published in 1787 alone, 820 in 1788, 3,300 in 1789, 3,120 in 1790, 1,920 in 1791, 1,290 in 1792,…for a total of more than 13,000 different pamphlets in the thirteen years between 1787 and 1799. Similarly, only around 30 periodicals, consisting mainly of newspapers and reviews, were being published in Paris in the 1770s, while around 250 new periodicals began publication in Paris in 1789 alone, 350 in 1790, 110 in 1791, 120 in 1792, etc. But let us leave out the tumultuous late 1780s and early 1790s and look at the long-term trend. France’s first daily newspaper, the Journal de Paris, began to appear in 1777; France had eight daily newspapers in 1818, thirteen in 1827, and twenty-six in 1846. Before 1789, the French newspaper with the largest distribution, the Gazette de France, had a weekly circulation of 12,000. In 1803 the Journal des débats had a daily circulation of 16,000. In 1846 the Siècle had a daily circulation of more than 30,000, and the twenty-six dailies together had a circulation of 180,000.[40]

The initial eruption consisted principally of political works. The Moniteur universel and the Journal des débats, the two daily newspapers with quasi-official status, the first by virtue of its completeness, the second by virtue of its impartiality, both began to appear in 1789 and both continued on uninterrupted into the Third Republic.[41] The vast majority of the periodicals and pamphlets of the Revolution were short-lived and openly partisan, however. Through their publications, several partisan pamphleteers and journalists became important people who influenced the course of the Revolution. Abbé Siéyès’s pamphlet Qu’est-ce que c’est le tiers état? (What Is the Third Estate?) helped to precipitate the formation of the first legislative body of the Revolution, the National Assembly. Jean-Paul Marat’s incendiary L’Ami du peuple (The Friend of the People), published thrice weekly, contributed to the ignition of the Reign of Terror. Jacques Hébert’s irregularly appearing Père Duchesne (Mr. Earthy) spoke to the lower classes in their vernacular and encouraged their active participation in the Revolution. In contrast, the royalist Antoine Rivarol was just as unsuccessful with his thrice-weekly Journal politique national in saving the king’s head as he had earlier been with his pamphlets in promoting Abbé Mical’s talking heads and their mechanical salutation, “Vive le roi!”

The numerous political pamphlets and periodicals of the Revolution publicized its spectacles. They informed their readers of plans for various public events from fêtes to executions, and then after the events had taken place reported on how they had gone. Both the partisan publicists, with their excerpts and paraphrases of the speeches of party leaders, and the Moniteur and the Débats, with their presentation of both sides of a debate, promoted oratory. The Imprimerie Nationale (National Printing Office), established in 1791 for the purpose of publishing the legislation and official reports of the assemblies, also sometimes published the text of a speech, when the representatives of an assembly voted to award one of their number the signal honor of publicizing his contribution to the oratorical spectacle.

Popular prints made from woodcuts, engravings, and etchings and reproduced on single-sheet broadsides, whether for political or commercial ends, may have done the most to publicize the spectacles of the Revolution. Thousands of different prints were published, each of them in hundreds or thousands of copies. Through prints made from copies of paintings by Jacques-Louis David and widely distributed, his image of “Le Serment du Jeu de paume” and “Marat assassiné” became everybody’s image of those spectacles of oratory and blood, respectively. During the Reign of Terror, the Committee of Public Safety charged David with commissioning caricatures for propaganda purposes and having them printed in large numbers. David not only procured caricatures from other artists but contributed several of his own to this publicity campaign.[42] He was the Revolution’s image-maker, pageant-master, and P.R. director.

The dictator Napoleon understood the importance of public opinion better than any elected official did: “Public opinion is an invisible, mysterious power that is irresistible; nothing is more fickle, more nebulous, or more powerful.” As a result, he put a lot of energy into trying to control public opinion, by actively publicizing his own views and by keeping others from publicizing theirs. In 1800 he reduced the number of Paris newspapers that reported on politics, as most of them did, from more than seventy-five to thirteen, and in 1811 to four. He also compelled the survivors to print only favorable accounts of him and his activities. He assigned topics to journalists, outlined articles for them, and even dictated whole articles himself. His masterpieces were his Bulletins de la Grande Armée, reports from the battlefield designed for civilian consumption, many of them accounts of victories, colorful, overstated, and widely disseminated.[43] His armies were powerful, but they seemed greater than they were because of something even more powerful, the press.

France’s political leaders taught ambitious individuals in other fields valuable lessons about publicity. First, accounts and pictures of current events had a large and growing audience. Second, that audience was influenced by what it read and saw. Third, the beneficiaries of that influence were not only the actors in the current events presented but also their presenters, the authors and artists. These lessons did not go unheeded. After Napoleon’s fall in 1814, new, suspended, and underground periodicals began to emerge again, so that Paris had 150 periodicals by 1818, 350 by 1835, and 500 by 1860.[44]

Before the Revolution, only a few special-interest groups had had their own periodicals, for instance the lawyers’ Journal du Palais (Journal of the Palace of Justice), dating from 1672. As of 1827 the law and the courts were receiving, in addition to the irregular attention of the newspapers, regular coverage by ten specialized journals.[45] Vidocq’s trials figured prominently in at least two of them, the Gazette des tribunaux and the Observateur des tribunaux, and Vidocq himself received sympathetic treatment there.

The first French music periodicals just printed written music. The third quarter of the eighteenth century brought brief runs of journals containing learned essays. Then came the Almanach musical of 1775–83, which told Parisians when and where to find what music, performed and written. Almanacs were annuals, had their information organized according to the cycle of the year, and dated from the germination of printing, originally serving as guides for planting, harvesting, and other agricultural activities. F.-J. Fétis’s Revue musicale initiated regular reviews of Paris concerts.[46] The Revue musicale, founded in 1827, the Gazette musicale de Paris, founded in 1834, and the merged Revue et gazette musicale de Paris, formed in 1835, gave substantial publicity to the concerts of Paganini and Liszt.

Grimod de La Reynière’s Almanach des gourmands (1803–12) may have been the very first gastronomic periodical. In fact, the words gastronomie, gastronome, gastronomique and their English copies, although based on Greek roots, gaster (stomach) and nomos (law), were not coined until the beginning of the nineteenth century.[47] Grimod’s almanacs told what time of the year specific foods became available in Paris and also provided information about the restaurants and food shops of the capital. His Jury Dégustateur (Jury of Tasters) sampled dishes prepared in various Paris establishments and then either awarded or withheld from them a légitimation. This signified something like “legitimate,” or “according to law,” and perhaps made a certain amount of sense in that gastronomy was the “law of the stomach,” and that these gastronomes seem to have considered themselves its lawgivers. Carême, however, did not approve of the idea of culinary amateurs such as Grimod appointing themselves lawgivers to professionals: “Doubtless he had some good influence on culinary matters, but he played no part in the rapid progress which modern cuisine has made since the renaissance of the art.” [48] Grimod’s almanacs did much to publicize haute cuisine, but Carême was not among the practitioners he singled out for special praise.

Labourdonnais produced the first chess periodical in Europe, perhaps in the world, with his monthly Palamède (1836–40). When he died, Saint-Amant, who succeeded him as champion of the Café de la Régence, put out a second series of the Palamède (1841–47). When Saint-Amant went into retirement, Kieseritzky became the leading player in the café and the editor of a new chess journal, La Régence (1849–51). This succession of dual titles, champion and editor, reveals the final step in the development of the special-interest periodical into an organ of publicity, a development that proceeded from the learned journal or informational almanac to the opinionated review, with the power to make and unmake reputations, to the ambitious practitioner’s megaphone, an instrument of self-promotion.

The Age of Revolution was the infancy of special-interest periodicals as well as of national republics. Labourdonnais expressed satisfaction at having 263 subscribers to the Palamède; he judged 120 sufficient for survival. The Revue musicale had 223 subscribers in 1832. To judge from these figures, special-interest periodicals might seem to have had only lim-ited publicity power. But issues could be found in cafés, reading rooms, and other public spaces where they had multiple readers. And their readers tended to be people active and influential in the specialty; many of the readers of the Revue musicale, for example, were professional musicians, who not only satisfied but also guided the taste of Paris concert-goers.[49] In any case, the novelty and range of special-interest periodicals in Paris during the Age of Revolution testify to the breadth of the emerging belief in the power of publicity.

Publicity for the spectacles of virtuosity was not limited to specialinterest periodicals. Announcements, reviews, and descriptions of these spectacles also appeared in general-interest magazines, newspapers, broadsheets, pamphlets, and books. Advertisements for, and admiring reports of, Philidor’s simultaneous blindfold exhibitions in London appeared in many newspapers and magazines, including The London Chronicle, The Morning Post, The Sporting Magazine, The Times, and The World. Joseph Méry, coeditor with Labourdonnais of Le Palamède and a prolific author, published a long poem about Labourdonnais’s victory over MacDonnell in the 1834 international championship match, comparing Labourdonnais to Napoleon in Une Revanche de Waterloo (A Revenge for Waterloo). An Irish travel writer, Lady Sydney Owenson Morgan, published two books about France, the first of which, France in 1829–30, contains a precious description of a dinner prepared by Carême, at the end of which the host, M. Rothschild, “pointed to a column of the most ingenious confectionary architecture, on which my name was inscribed in spun sugar.” Heinrich Heine evoked the ephemeral quality of music through evanescent effigies:

Heine’s verbal caprice on a performance by Paganini appeared in the Revue des deux mondes, an influential review of literature, politics, and the arts, which later in the same year, 1836, published a travel piece by George Sand containing a fantasia on a performance by Liszt.[50]His body was resplendent with virile power; a powder-blue robe draped his noble limbs; his mane of black hair flowed over his shoulders in shining curls. He stood erect, firmly and confidently, like the statue of a god, and played the violin; it seemed as if all creation moved to his chords. He was the man-planet around whom the universe revolved to a celestial rhythm in a solemn ceremony. Were the beautiful calm lights that soared around him the stars of heaven? Was the sonorous harmony that radiated with their motion the music of the spheres, of which poets and seers have spoken in their visions?

The Moniteur’s report of Robert-Houdin’s show in Algeria brings us back to reality and to politics, the hard reality of colonial politics, which however was less Realpolitik than Phantasiepolitik. The report illustrates the presence of both publicity and spectacle in politics and demonstrates not only, as a report, the publicizing of a spectacle but also, in its report, the publicity power inherent in a spectacle:

The arrival of an extraordinary man working miracles had been announced in advance to the Arabs. When everything had been prepared for his expériences, the marabouts were not the least prompt to arrive. The efforts they had made to discredit this formidable competitor in the minds of their dupes would make the surprising things that were about to confound their understanding even more impressive.

It was no longer a matter of diverting and refreshing a curious and benevolent public; it was necessary to strike hard and true on crude imaginations and prejudiced minds.

On the day chosen for this astonishing expérience, the assembly was numerous. A fanatic marabout had consented to put himself in the hands of the sorcerer. He was asked to stand on a table, where he was covered with a transparent piece of gauze. Then Robert-Houdin and another person picked up opposite ends of the table and the Arab disappeared in the middle of a cloud of smoke.

At the sight of this, all the spectators fled tumultuously from the hall.…Finally, one of them, less terrified than his comrades, stopped them and said it was imperative to see what had become of the marabout. They retraced their steps and were not a little surprised to find him again safe and sound near the hall where the expérience had taken place. Pressed with questions, he told them that he had been as if drunk, unable to recall anything and unaware of how he had come to be where he was.

Today the marabouts have fallen into complete disrepute among the natives. On the other hand, the celebrated prestidigitator is an object of admiration for them.[51]

As Robert-Houdin’s Algerian show indicates, a stage performance could be, in addition to a spectacle, a vehicle of publicity. Balzac’s play Vautrin, whose eponymous protagonist and his adventures were widely known to have been based on Vidocq and his adventures, gave publicity to that detective. The play Paganini en Allemagne, which was written and performed in Paris shortly after Paganini made his début there, gave publicity to that violinist. The play La Czarine, whose plot was much concerned with the famous automaton chess player, a copy of which was made for the play by Robert-Houdin, gave publicity to that mechanician.[52] Conversely, a page could be a stage, when depictions immediately vivid to the mind’s eye of readers reproduced performances immediately striking to the eye or ear of audiences. Like theaters, printing presses are a kind of public space. Thus, while in many cases publications encouraged spectacles by giving publicity to them, they could also substitute for them.

Vidocq tried in various ways to make a spectacle of detection, but with limited success, because many feats of detection, although inherently spectacular, are necessarily performed in the absence of an audience. In order for them to become a spectacle, they had to be reenacted on the stage or translated into printed words. Vidocq did the first with his London exhibition of thieves’ tools, his own disguises, and himself, and the second with his Mémoires. Vidocq used his Mémoires to present his adventures as spectacles and to publicize them. The book sold fifty thousand copies within a year of its appearance, for its time a huge readership, or better, audience.[53] This was how detection became if not a true spectacle at least a pseudo-spectacle. The surge that the Revolution’s discharge of the press gave to the proliferation of spectacles was short-circuited in this case, so that the means of publicity lit itself up instead of lighting up a spectacle separate from itself; the publication substituted for the spectacle.

| • | • | • |

Republicanizing, performing in front of an audience, and publishing all began as efforts to bring something to the public. During the Age of Revolution, individuals in a broad range of occupations—in politics, theater, and the press as well as in chess, cooking, crime-detection, musical performance, and automaton-building—brought things to the Parisian public at a rapidly accelerating pace. Eventually the quantity of offerings made to the public reached royal proportions. For the ambitious, the effort became less one of bringing their offerings to the public than one of attracting the sovereign public’s attention. Many, the virtuosos conspicuous among them, attracted the public by magnifying the eye-catching or ear-catching aspects of their offerings. Publicization gave way to spectacle-making and to publicity, which often supported spectacle-making and sometimes substituted for it. That is how ended the reign of kings and the legally privileged and how began the reign of the public and its courtiers.

Notes

All translations of quotations from other languages into English are the author’s unless otherwise noted.

1. Louis-Sébastien Mercier, The Picture of Paris before and after the Revolution, trans. Wilfrid and Emilie Jackson (London: Routledge, 1929), p. 179; this work consists of excerpts from Mercier’s Tableau de Paris and Nouveau Paris.

2. Maurice Albert, Les Théâtres des boulevards (1789–1848) (Geneva: Slatkine, 1969; reprint of Paris ed., 1902), p. 71.

3. Alexis de Tocqueville, L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution, 2 vols. (Paris: Gallimard, 1952–53), vol. 1, pp. 95–96.

4. Mornet, Origines intellectuelles de la Révolution française, pp. 1–2.

5. Other historians have different terms for and somewhat different conceptions of the eighteenth-century development that is referred to here as the “publicization of critical discourse.”

Mornet (1933), as noted, provides much evidence of publicization, but refers to it only as “diffusion générale”; ibid., passim.

Augustin Cochin, La Révolution et la libre-pensée (Paris: Plon, 1924), distinguishes a campaign to “susciter une opinion publique” by “les sociétés de pensée” (p. xxx), a campaign he calls “la socialisation de la pensée” (title of the book’s first section).

Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger and Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1989; first published 1962), chap. 3, discusses “the genesis of the bourgeois public sphere [bürgerliche Öffentlichkeit].”

Keith Michael Baker, “Public opinion as political invention,” in Inventing the French Revolution: Essays on French Political Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 172, writes: “‘Public opinion’ took form as a political or ideological construct, rather than as a discrete sociological referent.”

Roger Chartier, The Cultural Origins of the French Revolution, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1991; first published 1990), p. 19, cites “the emergence of a new conceptual and social reality: public opinion.”

Arlette Farge, Subversive Words: Public Opinion in Eighteenth-Century France, trans. Rosemary Morris (University Park, Penn.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995; first published 1992), p. 198, concludes, “Something was emerging, something firm and solid: quite simply, the right to know and to judge, the right to expect the king to divulge his secrets.”

None of these historians, however, shows an interest in the general process of things becoming public. They all focus their attention on the formation of public opinion in politics. (Mornet and Habermas also devote some attention to the formation of public opinion in the arts, as a forerunner of public opinion in politics.) Thus their study of public things is twice narrowed, first to opinion and second to political opinion. And the development they trace is the formation of a new thing, whereas the development traced here is the transformation of old things, with, to be sure, novel consequences.

6. Roland Mousnier and Ernest Labrousse, Histoire générale des civilisations, vol. 5, Le XVIIIe siècle, l’époque des “lumières” (1715–1815) (Paris: P.U.F., 1959), p. 121.

7. Hillairet, Dictionnaire historique, vol. 1, pp. 294–96, 297–98, 577, 582; vol. 2, pp. 76, 602; Marie-Blanche d’Arneville, “Jardins,” in Dictionnaire Napoléon, p. 964.

8. Mornet, Origines intellectuelles de la Révolution française, pp. 306, 314–15. Mornet cites the proliferation of various kinds of social spaces in support of his thesis tracing the Revolution back to “la diffusion des idées nouvelles.” Similarly, Cochin cites the proliferation of various kinds of “sociétés de pensée” in support of his thesis tracing the Revolution back to the common organizational form of these social spaces; Cochin, La Révolution et la libre-pensée, pp. xxviii–xxxvii. But neither Cochin’s conception of “la socialisation de la pensée” nor Mornet’s conception of “la diffusion des idées nouvelles” resembles the conception of “publicization” presented here.

9. On the fairs: Fournel, Vieux Paris, chap. 3; Maurice Albert, Les Théâtres de la foire (1660–1789) (Geneva: Slatkine, 1969; reprint of Paris ed., 1900), passim; Marian Hannah Winter, “Le Spectacle forain,” in Histoire des spectacles, ed. Guy Dumur (Paris: Pléiade, 1965), pp. 1435–60; Isherwood, Farce and Fantasy, chaps. 2, 6. On the Boulevard du Temple: Fournel, Vieux Paris, chap. 4; Albert, Théâtres des boulevards, passim; Marian Hannah Winter, The Theatre of Marvels, trans. Charles Meldon (New York: Blom, 1964), passim; Michèle Root-Bernstein, Boulevard Theater and Revolution in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms International, 1984), passim; Isherwood, Farce and Fantasy, chap. 7. On the Palais-Royal: Saint-Marc and Boubonne, Chroniques du Palais-Royal, passim; Hillairet, Dictionnaire historique, vol. 2, pp. 219–22; Berthier de Sauvigny, Nouvelle histoire de Paris, pp. 379–82; Isherwood, Farce and Fantasy, chap. 8.

10. On some theaters paying the Opéra to extend its privilège: Isherwood, Farce and Fantasy, chap. 4. See also Root-Bernstein, Boulevard Theater and Revolution, pp. 45 (some theaters ignored the Opéra’s privilège), 57–62 (some theaters paid the Opéra to extend its privilège), 201 (number of Paris theaters); Nicolas Brazier, Chroniques des petits théâtres de Paris, 2 vols. (Geneva: Slatkine, 1971; reprint of Paris ed., 1883; first published in Paris, 1837), vol. 1, chap. entitled “Théâtre de l’Ambigu-Comique” (some theaters exploited loopholes in the Opéra’s privilège); vol. 2, pp. 295–302 (amateur theater in eighteenth-century Paris). On attendance at the Comédie-Française beginning to set records in the 1760s: John Lough, Paris Theatre Audiences in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957), pp. 174, 272–73. On the opening of forty-five new theaters during the Revolution: Theodore Zeldin, France 1848–1945, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973–77), vol. 2, p. 709.

11. For population figures: Chandler and Fox, Three Thousand Years of Urban Growth, pp. 17–20; Chevalier, Laboring Classes and Dangerous Classes, pp. 181–82. On public reading rooms: Zeldin, France 1848–1945, vol. 2, p. 355. On public bathtubs: Erwin H. Ackerknecht, Medicine at the Paris Hospital, 1794–1848 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1967), p. 151.

12. For the eighteenth-century café counts: Mornet, Origines intellectuelles de la Révolution française, pp. 281–82. For the 1807 café count: Prudhomme, Miroir historique, vol. 1, p. 283. For Philidor’s observation: Twiss, Chess, vol. 1, p. 150.

13. For the 1789 and 1803 restaurant counts: Grimod de la Reynière, Almanach des gourmands, vol. 1, p. 163. For the 1820 restaurant count: Zeldin, France 1848–1945, vol. 2, p. 739. For the patisserie count: Carême, Pâtissier royal parisien, 2d ed., vol. 1, pp. xli–xliii.

14. Isherwood, Farce and Fantasy, pp. 89–101; Brenet, Concerts en France, pp. 115–16, 130–33, 356–82; Young, “Concert,” in New Grove Dictionary, vol. 4, p. 617.

15. Cochin, La Révolution et la libre-pensée, pp. xxviii–xxxvii; François Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution, trans. Elborg Forster (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1981), pp. 187–91; Chartier, Cultural Origins of the French Revolution, pp. 16–17.

16. Daniel Ligou et al., Histoire des Francs-maçons en France (Toulouse: Privat, 1981), pp. 29, 67, 79–80, 164–66.

17. Cochin argues that in a “pure democracy,” whether of a “société de pensée,” of a national government such as France had in 1793–94, or of any other sort, there will always develop a division of the people into two unequal groups, a small active group and a large passive group, a few “effective militants” and “flocks of adherents.” Similarly, the present study suggests that in the publicization of an activity there often develops a division of people into performers and spectators. Cochin, La Révolution et la libre-pensée, p. 5.

18. Mona Ozouf, La Fête révolutionnaire, 1789–1799 (Paris: Gallimard, 1976), pp. 20, 38–40.

19. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “J. J. Rousseau, citoyen de Genève, à M. d’Alembert sur son article ‘Genève’ dans le septième volume de l’Encyclopédie ” (generally called “Lettre à d’Alembert sur les spectacles”), in Oeuvres complètes de J. J. Rousseau, 17 vols. (Paris: Armand-Aubrée, 1830–33), vol. 1, pp. 405 n (first quotation), 395 (second quotation). See also Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Les Rêveries d’un promeneur solitaire, in Oeuvres complètes (Pléiade ed.), vol. 1, p. 1085.

20. David Lloyd Dowd, Pageant-Master of the Republic: Jacques-Louis David and the French Revolution (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1948), passim (“Triomphe de Voltaire,” pp. 46–53); Anon., Collection complète des tableaux historiques de la Révolution française, 3 vols. (Paris: Auber, an X (1802)), vol. 1, tableau 55, facing p. 220, “Triomphe de Voltaire.”

21. F[rançois-Victor]-A[lphonse] Aulard, Les Orateurs de la Législative et de la Convention, 2 vols. (Paris: Hachette, 1885–86), vol. 1, pp. 6–8, 28–40; [Louis-] Sébastien Mercier, Paris pendant la Révolution, ou Le nouveau Paris, 2 vols. (abr., Paris: Poulet-Malassis, 1862; first published Paris, 1798), vol. 1, pp. 275–80.

22. Pierre de Vaissière, La Mort du roi (21 janvier 1793) (Paris: Perrin, 1910), pp. 61, 90, 129.

23. E. J. Delécluze, Louis David, son école et son temps (Paris: Macula, 1983; reprint, with plates added, of Paris ed., 1855), 12th unnumbered page of plates between pp. 264 and 265.

24. [Louis-Antoine Fauvelet] de Bourrienne, Mémoires de M. de Bourrienne, ministre d’État, sur Napoléon, le Directoire, le Consulat, l’Empire, et la Restauration, 10 vols. (Paris: Ladvocat, 1829), vol. 3, p. 214. See also the quotation of Heinrich Heine in chapter 4 of this volume, p. 153.

25. Las Cases, Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène, vol. 1, pp. 403–4; vol. 2, p. 408.

26. Paul Ginisty, Mémoires d’une danseuse de corde: Mme Saqui (1786–1866) (Paris: Charpentier and Fasquelle, 1907), chaps. 6, 7, 8 (the quotation is on p. 86).

27. Marie-Antoinette Allevy, La Mise-en-scène en France dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle (Geneva: Slatkine, 1976; reprint of Paris ed., 1938), pp. 2, 22, 63, 114–15; Gautier, Histoire de l’art dramatique, vol. 2, p. 175.

28. Winter, Theatre of Marvels, pp. 57 (first quotation), 176 (second quotation), chap. 9; Michèle Richet, “Le Cirque” and Tristan Rémy, “Le Mime,” in Histoire des spectacles, pp. 1520–29 and 1493–1509, respectively.