Part Two

In which there is great progress in finding informants, in getting closer to them, and most of all in understanding them through the use of indigenous categories. In which also there are many dead ends, as in trying to find weavers; and distractions, as in trying to keep the household running efficiently, dealing with the death of a family member, and using police contacts to advantage.

6. A Shift in Technique

During my first months in Banaras my problems, however, were less of interpretation than of getting to know people. I became panicky as Sawan passed me by, followed by the next monsoon month of Bhadon, and still I had located almost no “cultural activities.” I went to talk to my local guide and everybody’s mentor, Dr. Suryanath Gupta. Dr. Gupta always had a mysterious, satisfied expression implying a knowledge of many things that would never get shared simply because you couldn’t ask him about them since you didn’t know what things they were. You could guess at random, as I did, and sometimes hit the mark. When I asked about the Ramlila, Dr. Gupta became suffused with excitement and talked rapidly for hours. Or, when you missed, as when I asked about the indigenous system of wrestling in akharas, he could look as grumpy as a child and say something like, “Oh, a lot has been written on that already,” or, regarding the culture of a particular community, simply, “No such thing exists.” But all these idiosyncrasies aside, Dr. Gupta was one of the most knowledgeable people in Banaras on the subject of the city’s social and cultural life.

He told me that at that very time an important mela, or fair, called Sohariya Mela was in progress, so called because it lasted sixteen (solah) days. It was based at Lakshmi Kund (one of the many artificial tanks, or water reservoirs, in Banaras), centered on the worship of Lakshmi, and was the occasion for the display of handicrafts by the potters of Banaras, who rivaled one another in their production of toys and especially of images of Lakshmi for the mela. It sounded fascinating. But the third general rule I discovered about fieldwork (after the ones about legendary places losing their charm and people in the same mohalla being unknown to one another) was that the description of an event is very different from the direct experience.

To begin with, I had no idea what a mela was, apart from the expectation of dust and cheap stalls where everything could be bought for a few pice—both ideas derived from a short story by Premchand read in my school days. I had been to the Nauchandi mela in Meerut as a child, but all I remember is grown-ups around me saying, “Let’s go to Cozy Corner!” My imagination had soared, and I had expected scones for tea, perhaps cakes and macaroons. I was reading Enid Blyton’s school adventures at the time and relished words like “marmalade,” “fruitcake,” and “pie.” Cozy Corner turned out to be the exact opposite of all its name suggested, a completely desi, or indigenous (in the worst sense), place, almost dirty to my anglophile eyes. The grown-ups ate hot, greasy pakora-fritters.

There is an easy way to find out where something is, and accordingly I took a rickshaw and directed, “Lakshmi Kund!” As soon as vendors and balloon sellers appeared, I hopped off. Again, my timing was wrong. It was the middle of the day and the magic was gone. I was to find it very different when I came again the next year with three women all bearing trays to worship Lakshmi, arriving in the evening and staying on as darkness fell. But this first time, because I was keyed up with expectation, because I was still so ignorant, and because it was the middle of the day, I found nothing.

There were stalls on either side of the lane from about a furlong before the tank to the tank with its neighboring temple. Most of these were manned by children, their parents being busy with more productive work. Children take over many stalls around mid-day as mothers wash and cook, fathers bathe and eat, and youngsters are made to sit still after school. The stalls all sold clay products, mostly images of Lakshmi and a variety of toys, with some toys like the Ramlila bow and arrow already making an appearance, Ramlila being next on the festival calendar. The variety was not as great as it seemed at first sight. After I had exclaimed over a little clay T.V. set and bought a few other charming oddities, there was no attraction in the stalls. I made some effort to find out from the children where they lived, who made the toys, how, and so on, but they were really not the people to ask and did not relish being interrogated. I have found it awkward to approach children as informants on the whole because it is difficult for me to weigh their interest against their indifference and to talk on their level. My worst moment was when I started having a good time with a group of five or six dusty little boys on a street near Lohatiya, beginning to understand their game, their fun, and their personalities. Before departing I wanted to write down their names and where their homes were, driven by my familiar greed to know one more person that I could come back to later. Then I made the gigantic blunder of presenting each with a coin for a treat. Like wildfire the word spread over rooftops and through dusty galis, “Get your name written and receive a coin! Come and get paid for your name!” I have never made a less dignified retreat.

After plodding through all the lanes of the Lakshmi mela, I thought that I should at least enter the temple at the center of it all. There were a few worshipers here, along with bathers at the tank, and a little more to observe. But once inside, I could feel everything floating away from me. The old uneasiness I feel in temples came back, along with questions not to be resolved by mythology: “What is this? Who is this? What do I do? Why is everyone doing what they do?” I also never know what to focus on as observer in a temple and try to take in everything at once: the architecture, the sculpture, the ritual, the social drama…After this experience of my first mela, I was truly at a loss and in need of conversation. I had heard of Vishwanath Mukherjee for some time; an amateur author, historian, and ethnographer, he seemed to vie with Suryanath Gupta for the position of greatest expert on Banaras. I sought him out at his place of work, the Indian Medical Association, where he was on the editorial board of Apana Swasthya (Our Health). I prepared a list of questions for him, of which one was, “What is a mela?”

Vishwanath Mukherjee was confused by my topic, popular culture. Like most people I talked to in the beginning, “culture” meant for him the great musicians and writers of Banaras, and “popular culture” was a contradiction in terms. He kept listing for me all the “great” people I should speak with, and they still weigh on my conscience as a task never accomplished. I kept trying to elucidate my purpose to him. When I told him that I had been to a mela but could not comprehend it, and that I had heard of others like the Nakkatayya but couldn’t guess the sense of them, he seemed to perceive a logic. He never did tell me about melas, but we came to another milestone in my research.

“You know the most special thing in Banaras?” he said that first day. “People like to go on picnics.”

“Picnics?” I asked incredulously. “Yes, they go outside, cook, and eat.”

“Since when has this been going on?” I questioned, convinced that it was a thoroughly middle-class activity, at best learned downward through “trickling” or “seepage.”

“Since always. Banarasis have always loved to do this,” he answered complacently.

“And does it continue?” I persisted, wondering why, if he was correct, I had come across no sight or mention of this activity.

“It was popular till 1947.” I discovered later that most people used 1947 as a landmark in their memories to denote some major change during their lives. Or they would say, “twenty-five to thirty years,” implying 1947, or simply, “Azadi ke samay se” (“Since Independence”). They meant, as it would turn out after further questioning, within one generation, or within their living memory, that they had been familiar with something in their youth but that their children were not.

The lead that Mukherjee gave me was confirmed in the most direct way possible less than a week later. I was talking to Ramji Sahgal, owner of Khatri Medical Hall in the heart of Chauk, as well as a textile store across the street and a store of dried fruits and fruit drinks. When he had a visitor, instead of regaling the person with the usual tea, he would offer, say, a glass of apple juice—but unlike the customary tea offered at each visit, his refreshment was limited to the first visit because it was so much more exotic, special, and expensive, or so it was in my case. Ramji Sahgal is a scion of one of the old, established families of Banaras, not one of the rais, or aristocracy, but on the fringe. He is active in his community and is founder-member or secretary of assorted cultural organizations such as Nagari Natak Mandali (Association for Nagari Theater), Ved Vidyalaya (School for Vedas), Sangeet Parishad (Music Club), and so on. He speaks in a reserved, somewhat pompous way, as befits his position—which I have always found best defined by his location, that is, sitting in his open-fronted shop, exactly where the galis turn for the famed Manikarnika cremation ghat, governing the vista of what is therefore the most crowded, interesting, and important part of Chauk. I made friends with him because of his location.

On that day, after a great deal of interesting talk, I put the question to him, “What are the leisure activities of the people of Banaras?”

He replied promptly without a moment’s thought: “Bhang chhanana (straining bhang, the local narcotic), washing your clothes with soap, and bahri alang jana (going outdoors).” Amazingly, he managed to look pompous and dignified even as he said this.

I was somewhat alarmed to feel reality slip away from me so swiftly, and to gain time I asked my formulaic question: “Has it changed? How is it changing?”

He said, Yes indeed it had changed. The first, bhang, was now too expensive; for the third, bahri alang, there was now less time and money; but the second continued to be the “hobby” (his term) of the people of Banaras.

I left, still in a daze, trying to picture Ramji Sahgal doubled over, scrubbing the shirt from his back with soap.

He was dead on the mark: soap was a valued object and a precious symbol of luxury and good living, but no amount of observation could probably have brought the fact home to me, with my preconceptions on the subject, had it not been stated to me so blandly. Many disconnected pictures fell in place: families gathered at public taps working up a joyous lather of cleansing; a Hindi movie I had recently seen where the middle-class couple comes to the verge of breaking up because the soap of the otherwise docile husband is used by the wife; the powerful advertising industry’s explicit focus on soap.

Thus I entered yet another phase of my fieldwork, in which I started what may be called a systematic search, asking everyone I met about “indigenous categories,” in this case bahri alang, soap, bhang, and water. For the uninitiated reader, bahri alang is best explained by its literal translation, “the outer side,” and refers to the activity of going outside and away. When I thought about it, “picnicking” was quite an acceptable way of putting it, though in my mind I forced an “indigenous” to prefix the “picnic.”

The next time I visited Mohan Lal, I put to him the question, “What is the manoranjan (entertainment) of you people?” His answer: “Bathing in the Ganga…exercise in the akhara…bahri alang…nahana-nipatana (defecation and bathing)…” He was one of those old men who, partly because they have been extremely energetic their whole lives and feel incapacitated with old age, develop a habit of claiming for everything that it is now finished. So Mohan Lal added, “Now everything is forgotten. Ten people would get together, go out, have bhang. Now there is no money, no interest. It’s also a lot of trouble. Liquor is quicker.”

But by that time, I had stopped taking everything informants said at face value. I could dig beneath the surface of their speech quite effectively to uncover the latent preferences and prejudices. I also learned to change my style of questioning from the innocuous, “What is ——?” or “Tell me about ——,” which failed as surely as asking a preschooler (I was to learn), “How was school? What happened today?” With indigenous categories, I had possession of a key, I felt, with which to unlock people’s minds and mouths, one which never failed at its task. The element of surprise was essential in its deployment the first time. With a new woodworker friend, for example, I turned suddenly in the middle of a conversation about something else to ask, “How many times a year exactly did you go to bahri alang?” And Tara Prasad looked at me happily and chortled, “Well, we have to go to Sarnath and Ramnagar, as you know. And then in the Navratras…It adds up to quite a lot.” With my new metalworker families I would smoothly interject into a discussion of, say, poverty, “Then there’s the going out, the bathing…soap…that must cost quite a lot.” They would express appreciation of my perspicacity and proceed to elaborate in gratifying ways. By then also, if further documentation was needed, I had my first photographs of bahri alang revelers, on their way with bhang and lota (water pot) to the other bank of the river.

7. Woodworkers

In the first weeks of my progress with “the people of Banaras” I also met Tara Prasad, who eventually became the closest friend I made among the artisans, and again I use “friend” advisedly. One fine October morning, feeling it was getting “too late”—a feeling that began coming to me more and more often—I decided to explore Khojwa. An excellent article in Aj, the local Hindi daily, had informed me that Khojwa was where the wooden toymakers lived. I had with me that day my sister-in-law, Bandana, a serious young woman doing her Ph.D. in industrial sociology at Kashi Vidyapith. With a good idea of “what sociologists do,” I did not wish to bore her, so I didn’t loiter as I would have if alone. (I expected her to tire very quickly and to ask me pointedly, “What are you searching for?” She had already put me on guard by asking innocently, “What is your universe?”) I put on an appearance of knowing my mind, alighted from the rickshaw at the first sight of wooden toys, and started talking to a young man tending a shop. It turned out to be an elaborate introduction to the industry and the people, far better than I would have had by wandering around.

The shop was called Arya Kashtha Kala Mandir, the Aryan Temple of Wooden Art, and the young man was Ram Chandra Singh. He was reading, had no customers, and was more than happy to show off his expertise and knowledge. With pity for my ignorance, which I was at pains to emphasize through word, gesture, and facial expression, he recounted the history of woodwork in Khojwa, the caste and social composition of the workers, and the nature of production. Everything was very clear except, as usual, his own family and social background. He was one of ten sons—could I have got that right?—whose names went thus: Rameshwar, Parmeshwar, Chandreshwar, Muneshwar, Gyaneshwar, Amiteshwar, Gopeshwar, Shrimanteshwar, and then, for some inexplicable reason, Raj Kumar. There was also one sister, Mina Kumari. Of course! The two glittering stars of the Bombay screen! For reasons of my own—personality, family background, academic training—I always felt awkward and unsure in probing family relationships and processes, considered the subject irrelevant, and tried to relegate it to later meetings. An hour with him felt otherwise like time well spent. The only other discomfort I experienced was in pretending I shared his taste when he began showing me the choicest examples of Banaras woodwork. Only the handmade wooden idols struck me as wonderful, utterly lifelike and charming. Who made those? Where did the ideas come from? Usually from calendars, I was informed, and my heart sank. I had expected something more “artistic” and creative. Ram Chandra then unrolled some calendars for my benefit and boasted particularly about one that he was going to order the craftsman to make next: the Panchmukhi (Five-Faced) Hanuman. I seized on the mention of the craftsman: where was he, how could I meet him? And immediately another young man, Kailash Kumar, who had meanwhile wandered in, volunteered to take me around to the craftsmen’s homes the next day.

That was how I was introduced to Tara Prasad, though I had to keep him too for another day because of Kailash Kumar’s priorities.(see fig. 5) Kailash’s uncle had a factory of stone goods in Khojwa, and, as often happened, Kailash saw me as overimpressed by Ram Chandra’s products and wanted to overwhelm me with his own. He was also educated, and doubtless full of vague ambitions, some of which I vaguely seemed to touch, being from some vague faraway place in his vague mind. I inspected the stone products: a seemingly unvarying array of candlestands, incense holders, ashtrays, oblong and round boxes for unnamed things. I tried to reason that this apparent sameness was explained by the lathe they depended on, which could only whirl the stone around rapidly like a potter’s wheel while the workers scooped with different files to mold the stone. But inwardly I accepted that it was for sheer lack of imagination. I saw some more “factories” according to Kailash’s taste, had tea and pan repeatedly, and extracted promises from everyone for hosting my further visits, all necessarily after Diwali. Most people offered to tell me the whole history of carpenters, toymakers, and stoneworkers in Banaras when I was ready (that is, after Diwali), and one grand man, Ram Khilawan, father of the ten sons, directed me to a publication, Singh Garjana, for enlightenment. This, as I immediately guessed, was the laudatory mythological history of his caste.

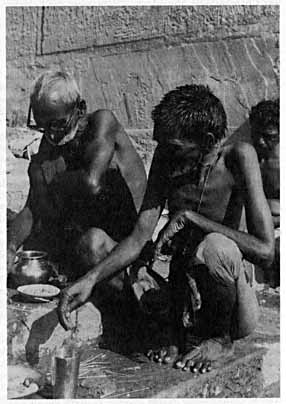

Tara Prasad (right) performing a pinda ritual

I went to Khojwa again the next day, though I almost never went to the same place two, leave aside three, days consecutively. Feeling like a thief, I took a different route, afraid to bump into those who had already assured me my work was over. Of course I lost my way and found myself returning to Ram Khilawan. It turned out to be no problem at all to meet him again, and I took one unplanned step forward in overcoming my diffidence and tendency to shy away from sudden familiarity and contact. During a brief chat he told me of what local people had drunk in the past, something called madag, made out of opium, but I felt utterly ignorant of the realm of drugs and intoxication conjured up by his talk and intuitively wished to ignore the whole subject.

When I knocked at Tara Prasad’s door, hungry and despondent, I discovered that he wasn’t in. His wife was illiterate and spoke only Bhojpuri. I for my part spoke “pure” Hindi and had always assumed that I would be able to follow Bhojpuri—or for that matter any “dialect” of Hindi—when the necessity arose. But this particular speaker showed me the fallacy of my simplistic and arrogant beliefs. Lilavati was crusading in her own way for the cause of those who resisted the categorization of Bhojpuri as a mere dialect and had plastered Banaras with posters, usually erasing notices in Hindi, urging, “Kewal Bhojpuri!” (“Only Bhojpuri!”). She spoke fast, with the unconcern for listeners that those little experienced in public life particularly have. Every time I tried to slow her down or to translate her words into mine, she either froze into uncomprehending silence or steamrollered right over me with her own thoughts. I had to admit to myself that I could not follow her and that she had no idea what I wanted, but I was determined to make it work. I sat ensconced on the wooden seat, she before me on the floor, and we talked to and fro for an hour, repeating much, and mostly at cross-purposes. A few things became clear, however. Tara Prasad was very sick. There was no money in the house. It was near Diwali and the wages for past work had yet to be collected. But how? Tara was too ill to go anywhere. His wife never stepped out, she did not like to meddle in all this. Why was he not resting then, where was he? He had decided to make his way to the doctor, resting and going, stopping and walking, as she put it, which I thought was wonderfully descriptive.

Very soon I was on my old track again, pleading with her to let me somehow help them. She resolutely warded off my offers, vague as they were. I’m not sure what I had in mind— perhaps finding out which route Tara Prasad had taken, following him, and helping him by the elbow to the doctor’s. I knew I didn’t have the courage or the confidence to take out some money and hand it to her. Thinking over the scenario many times in my mind, I concluded that giving her money would seem the height of insult, sitting there as I was, an uninvited and uncomprehended guest.

Even as my heart grew heavy at the hopelessness of poverty, and no less at the physical seclusion and resignation of this woman, as an anthropologist I was mentally noting “useful” facts, such as the name of the doctor patronized, one could say, by the woodworkers of Khojwa, or the economic, educational, and gender divisions that characterized Bhojpuri and non-Bhojpuri speakers. To file away information thus, even while expressing and indeed experiencing sympathy for a plight, always aroused in me the anxiety that I was reducing the situation to a drama, even a farce. Can one be detached and concerned at the same time?

Empirically speaking: yes. I was often both. I realized, however, which attitude had precedence for me. I obviously had a proclivity for detached observation: I was making a profession out of it. It took me a few more years and some well-intentioned but misguided efforts to grasp how I could also mark a well-defined space for acting on my other proclivity: to interfere in areas I designated as problematic.

My next visit to their house witnessed Tara Prasad properly medicated and restored. Displaying his unlabeled bottle of violet mixture to me like a trophy, he greeted me hospitably and in the right state of mind to take time off for conversation. As all further visits revealed, he was as busy as only the grossly underpaid piecework wage earner can be: he had to get through the first stage of carving at least ten statues every day. I could only sit by him and watch, calculating that one question per five minutes was all I should subject him to.

Tara Prasad’s home was approached by a narrow gali—six feet across—that branched off the main road of Khojwa about two or three hundred yards after the bazaar began. I could take a rickshaw till the gali; indeed I felt it was essential. The main road itself was not too broad, and walking on it could be positively dangerous, with its bullock carts, hand-pulled carts, and speeding rickshaws, all piled high with heavy sacks, heading toward the grain market of Khojwa. For Khojwa’s importance did not lie in its being the residence of woodworkers; it was known and feted as the second most important wholesale market for grain in the city, after Visheshwarganj.

The market was in South Khojwa, and I kept a distance from it for the longest time—traders and so on, after all, with their Vaishya (trading caste) values and brazenly economic motivations—until I realized what a unity a mohalla constitutes. Most of the points of interest that Tara eventually led me to, such as akharas, wrestling matches, Ramlila stages, temples, and meeting places for late night music, were located in the market, as were scores of articulate and culturally active men, all traders. I confronted yet another prejudice I had grown up with: a trader, I suppose I had imagined, was only half a real person, being engrossed in profit maximization; I discovered rather swiftly that traders were, in spite of their profession, as impressive as my artisans in their preference for living well.

No rickshaws entered Tara Prasad’s gali, nor could I bring myself to stay on my bicycle in such a narrow space—even after I started riding a bike everywhere—though everyone else in Banaras could do it to perfection. I always walked, which itself needed the elaboration of certain techniques. If a bell-ringing bike announced itself as you were walking along, you had to turn to the wall quickly and hug it, hoping that the pedals wouldn’t scratch you or the bike squish some fresh cow dung on you. Or, if you were near a step, you simply ascended it and waited at the front of a house for the bike to pass. As in Chauk, every house was raised a few steps, which helped when the place was full of rainwater, slime, mud, and washed-up garbage, but what other purpose this feature served I could not discover. A few Banarasi informants told me that it was the “seat” of the house, that houses were always built with “chairs” to sit on.

As I approached Tara Prasad’s house, I always had moments of trepidation, for just there were three or four viewing galleries: a woman selling cheap packaged foods on a little platform, a man carving in a windowless room open to the street, and a housewife and mother inevitably massaging her children out on her verandah. These would all inspect me thoroughly and, seeing me often, must have felt they had a certain responsibility toward me, for as I appeared they would announce, “Go on, they’re at home” or “Tara’s out, but Mangra’s mother is in.” If I, whose job was to meet strangers, felt the neighbors’ inquisitiveness so keenly, what did my hosts themselves feel? I sometimes wondered. Were they subjected to taunts, cross-questioning, accusations of accepting money, of being in league with the government, or simply of being made fools? All these were problems mentioned obliquely by less-willing informants; of my closer ones, none ever complained that my frequent visits caused them any trouble.

The neighbors, in any case, were clearly not malicious, simply torn by curiosity. Why did I not incorporate them into my widening net of informants and settle the matter once and for all? Even if I had done so, there would still have been “neighbors”: for every person you get to know, there are a dozen to watch you. You also have limited resources; if you concentrate on one person or family, you cannot make an equal effort to become intimate with others simply because they appear along the way, so to speak; it is a draining proposition. Most of all, I would say, I could not summon up sufficient intensity to overcome the hurdles their different personalities and situations threw up. To make one conquest itself produced a certain relaxation of tension (“Ha! I am moving to Phase II”) and weakening of effort. Then there was the element of chance—Tara Prasad had drifted into my orbit quite without planning—and the still-larger element of compatibility. Mohan Lal, Tara Prasad, and all those I got to know equally well were ordinary people in most respects but different from others in one: they had the imagination and the generosity to extend to me their friendship. By some trifling mannerism or characteristic, they had stuck out in an anonymous crowd in the first place; through some further qualities they made it possible for me to get to know them well. I did not feel the same way about most of their immediate neighbors.

I did make a conscientious effort to keep up the momentum, pushing my courage and aggressiveness to their limits. At Mohan Lal’s, my earliest visits were enough to make passers-by pause, stare, and try to overhear what this short-haired, smartly dressed young woman and the blind and deaf old man in tatters could have to say to each other. The shop itself, with its front overhanging the lane, was almost part of the public space. As for neighboring shopkeepers, it always seemed to me that they had far more leisure than was normal, and they inevitably assumed various poses in their shops that gave them the maximum view of me. Mohan Lal minded none of this, and, adding to my embarrassment, we both had to shout because of his partial deafness.

The next family I tried to get to know in Kashipura took much longer to accept me. I turned into a little lane—three feet wide—at random, and there before me in a cobbled square was a well and a chabutara (brick platform), that excellent device for outdoor recreation. All around were houses opening to the square. The one directly in front of me was the largest, and in its front room, the workshop, squatted half a dozen men working on silver, an earthy sight, if there ever was one. Their smooth-chested, muscular bodies glowing in the embers of their own fire, which rose and fell with the bellows, their bare-floored workshop with tools of all sizes on the walls, and nothing but metal in different degrees of readiness all around—no matter how I have tried to squash this crude association, the memory has always left me with the aesthetic satisfaction of having seen something totally picturesque.

I was in the uncomfortable position of standing on the ground a few feet beneath them, trying to interrupt five or six working men with no very precise query. They played deaf and dumb for a while, then I think asked each other, “Who is she? What does she want?” I was totally intimidated and would have run away if I could have, but it was easier to hold my ground. Finally, I said, “May I come in?” I was given a folded sackcloth to sit on, but work continued on all sides as usual. That first day I got little information from them, but I was content simply to sit and watch them while they decided whether it made any sense to take a few minutes off to talk to me. Meanwhile, a crowd of children repeatedly gathered at the doors and were shooed off incessantly for blocking the light and wasting the men’s time. That the males in the family were less irritated by my disturbance of their work than simply shy and distrustful of me became clearer when I started photographing the children. My camera worked as a wonderful icebreaker. The men began to laugh, joke, and talk, and though they did not look at me directly, they made me feel welcome.

It was even more difficult to get to know woodworkers because the lathe operators worked in groups in shops that were open to the street and were busy, crowded, dusty, and noisy with whirring lathes. It was always more difficult to approach a group of men than an individual, and it was nearly impossible to interrupt a group at work, especially with the deafening machines nearby. I began seeking introductions. For every person I knew, I would ask to be introduced to one more. Tara Prasad became my assistant as well as my informant. Not only did I peep into all the processes of his and his family’s life but also I could come to him with any question and, for all his resistance, pester him for an answer. Often I would simply show up and say, “Take me to so-and-so.” He would hem and haw but was irretrievably amicable enough to do it.

To the end he was uncomfortable at my “interviews.” When I requested, “Take me to your sardar, the head of the Vishwakarmas,” he literally jumped. “What do you want to ask him? What are you trying to find out?” On another occasion I asked him if he could take me to the widow of a man mentioned in my records as an important cultural patron. His dismayed, by then familiar, reaction: “What shall we tell her? What will you say?” It was useless to remind him of my project or to explain that I needed to know others as I knew his family, because he thought of me as nothing but a friend. My project had never been that clear to him to begin with, and he had relegated all knowledge of it to oblivion. Once, telling him that I simply must speak to more woodworkers but was unable to do so, I asked, Would he please introduce me to four friends? There followed an old-style anthropological encounter. I sat on the single wooden seat in Tara Prasad’s house, his friends squatted on the floor, and I asked them questions as everyone else listened in. I have never used the information I gathered there. It was a silly tactic that turned out all wrong, nor did it make Tara Prasad understand that part of me better.

It must be said that Tara was a wonderful person whom I grew to love, but he was too stubborn and taciturn and, as I was always aware, far too busy to be a good informant and assistant. The lesson I was learning with Mohan Lal was reinforced: the reluctance of people to talk, to be interviewed, to be pinned down, was really their reluctance to be objectified. I measure my growth by my increasing ability to see the validity of their side of it, to drop the effort at outright objectification, to think of my informants as friends, and to accept that most of the time my information gathering had to be indirect. Tara Prasad revealed his specialness in wandering around the city, attending music programs and such events, pursuing his own activities with me in attendance. With him I came closest to fulfilling my somewhat neurotic and perverse dream of simply following an informant around everywhere without being seen or heard.

Tara had two rooms in his house, apart from the covered nook where he carved, the little bit of space that was the kitchen, and the tin shed with swinging door that must have been the toilet. In one room lived the family: the craftsman, in his sixties, perhaps; his Bhojpuri-saber-rattling wife; and the ten-year-old daughter, at the peak of pre-adolescent shyness. The second room was kachcha, of clay and thatch, and was rented out to a young migrant latheworker from the village, together with his family. The great thing for me was that this couple had an infant daughter exactly the same age as mine, giving me an honest, un-self-conscious topic of conversation right from the beginning. I could even bring my offspring along with me, and with these credentials in my hand, they had so much less distance to cover in formulating an image of me that they could accept.

Tara worked at home except for the necessary trips to the potters-painters who garnished his toys with paint and varnish and to the shopkeepers to barter for a few pennies his strenuously crafted, magically lifelike things of pleasure and worship. His home, accordingly, became one of my “centers,” to which I could head from any place in the city, to breathe easily, talk slowly and at leisure, enjoy the restfulness of knowing that the family accepted me and had ceased questioning my purposes. My daughter took some of her first steps there and visited them at all times of the day and night, eating every kind of meal and grabbing her compulsory naps. Something about the clean-wiped, bare floor, the emptiness of the room, and the fact that everyone there did what children find preferable anyway, that is, conducted all activities on the ground, made Irfana feel in harmony with Tara Prasad’s home. I remember her sitting crosslegged on the floor, around the age of one-and-a-half, being directed by her hosts to eat from a plate in front of her. She addressed the rice and was told, “Eat the vegetables! The vegetables! They’re on top.” And little Irfana dutifully looked up at the ceiling, wondering what other surprises her mother’s friends had for her. It was only just and fitting that she should have returned to Chicago, at the age of two, fluent not in English, Bengali, or Hindi, the languages of her parents, but in Bhojpuri.

8. Weavers

My success with woodworkers and metalworkers was not easy to match with weavers, and I made four abortive attempts to enter their world before I finally succeeded.

First attempt: I had decided to eschew the deceptive mohalla of Madanpura, which people in their ignorance insisted on calling the center of silk weaving, but I was not sure where to go instead. Meanwhile I was broadening my circle of archival investigation. One October morning I visited Bhelupura Police Station to track down the police festival records I knew existed. The station officer was not in and others were not in a mood to be obliging, so I started my customary stroll in a randomly chosen direction. Immediately I saw a painter painting signs in his wooden stall, getting all the spellings wrong, with some finished portraits of local politicians and grandees standing behind him. “A painter!” My brain, as Sombabu claims it does on such occasions, started whirring. I ordered a nameplate from him and began talking to him about his work and his family. My purpose had to be explained, and as soon as I did so, he introduced me to a stout old man with a Muslim goatee in the shop of Diwali firecrackers next door. Clearly “hanging out,” this man was sitting on a wooden ledge in the sun and swinging his legs; he was exactly the kind of man I wanted to meet. He took me to his home in nearby Gauriganj, where his sons and grandson wove saris. On the way I noted other weaving establishments, including a barely visible sign deep inside a lane that would be my next stop: Hai Silk House.

With the friendly Muslim, Kamruddin Ansari, I had the old problem of not knowing where to begin. Now I asked the family about their work, how long they wove, how much they earned, and so on. Now I asked them about their family life and what it had been like in Kamruddin’s youth. “We exercised a lot in those days, daily, and ate raw chanas [chickpeas, lentils] soaked overnight after we worked out,” he said, looking at his sons. “These youngsters don’t do anything. Look at their health!” Now I asked about their festivals and was informed that Hazrat Shish Paigambar (whoever that might be) had started the craft of weaving. The most titillating information was that they were, all weavers were, Ansari. They were not Julaha (the caste name for weavers, both Hindu and Muslim, in written sources and popular usage); Julahas did “coarse work.” Some days previously Mohan Lal had told me confidentially that they, the metalworkers, were Kasera, not Thatera, as some people believed. Thateras only did “coarse work,” he had whispered in my ear.

The sons at first largely ignored me as a friend of their father’s; Kamruddin, it was clear by their demeanor, they barely tolerated, thinking him old-fashioned and simply old. After a good hour of eavesdropping on our conversation and placing me in some way, they aroused themselves from their indifference and brought me their “family” albums to survey. It turned out that they had arrangements with rickshawallas and taxi drivers, who brought loads of tourists to their doorstep to be given an inside look at silk weaving and almost certainly to make some purchases. Kamruddin’s sons had fat packets of photographs sent them by their foreign friends and a diary crammed with addresses from Japan to Hawaii, traveling westward. It was Kamruddin’s turn to look amused and indifferent.

I did not stay long after that. I didn’t fancy having my name added to the crowded rostrum of foreigners, which would probably soon have happened. As I walked away, I heard a shout, and Kamruddin caught up with me. “Don’t forget,” he panted. “Don’t forget to write in your book that I used to eat raw chanas every day in my youth!”

Second attempt: Hai Silk House was a complex of three or four houses joined together, one used for dyeing, one for weaving, and so on. Mr. Abdul Hai sat in his baithaka, literally “sitting room,” on his gaddi, literally “seat,” the term used for all those white sheets and bolster pillows set out in every place of sale and reception. Mr. Hai was a middle-level businessman, not important enough to dismiss me offhand but hopeful that there might lurk a possible business deal in our exchange. He had a Hindu accountant whom I was itching to question about what it was like to work in a Muslim establishment, but I could only get enough of his name to gather it was Hindu and could come up with no ready excuse to include him in the conversation.

Mr. Hai claimed that thirty years back he had been an ordinary weaver and by the sheer skill of his hands he had risen to his present position of owning fifteen to twenty looms. He could describe the looms and the composition of the raw material in accurate detail. Then we came to “society and culture.” “Our work was started by…” he began; “Hazrat Shish Paigambar,” I finished, peeping at my previous page of notes and thinking again, whoever he might be. Abdul Hai did not take kindly to this display of knowledge on my part. “You seem to know all about us!” he exclaimed, not amused, scrutinizing me closely. “Hey, munshi!” he brought the accountant into the conversation; “How does she know everything?” Like me, he had been aware that the munshi and I formed some kind of a twosome, both being Hindus.

I was startled, to say the least. What did he think I was? A Muslim from a weaver family, disguised as a Hindu? A government agent? A foreign spy? I couldn’t guess, but the interview was over.

Third attempt: I made at least two other misdirected attempts to penetrate the weavers’ world. The first was through the agency of a sari businessman called Seth Govind Ram (different from Govind Ram Kapoor), who invited me to the satti, the wholesale market for saris, between 4:30 and 6:30 in the evening, when dozens of weavers would come to him, as to other middlemen in the satti, to sell their wares. I went, and sat on his gaddi, and saw the weavers come. He would recall my presence occasionally and jovially announce, “And here’s a bahanji (respected sister) from Chicago who wants to find out about weaver society! Tell her something!” And a few weavers would be directed to me. Red and hot and in deep pain at the whole proceeding, I would mumble, “Where do you live? What do you celebrate? How long have you been doing this?”

Fourth and penultimate attempt: My last unsuccessful foray followed a disappointing encounter with some potters at Reori Talab. It was the eve of Diwali and the wrong time to speak to them, as I should have known. So I breezed into a shop of firecrackers on the other side of the street which had a good display and where a team of three brothers and their uncle were putting the final touches on more explosives. I thought I was collecting data on the firecracker industry until I discovered that the work was seasonal. Two of the brothers did weaving; the third carried on a trade in mutton. The youngest, as I guessed him to be by his looks and energy, escorted me inside to see his loom. None of them seemed to be married, nor did they have a mother or sisters or any kind of a “proper” family or home, but all were exceedingly extroverted. I was uncomfortable with all the obvious evidence of bachelor existence and their readiness to welcome me into it, but in those days the last thing I could do was voice my thoughts or clarify a doubt plaguing me. I just went away and never came back.

In fact, both Gauriganj and Reori Talab are weaving areas, as is Madanpura, but the real centers are in the north of the city, the wards of Adampura and Jaitpura. I finally reached Jaitpura with the help of the “contact” of a “contact.” Like Govind Ram Kapoor, he was a silk yarn dealer, but one who actually knew weavers. He himself lived in Nati Imli, and next to his house, conveniently, was located the Bunkar Colony, or Weavers’ Colony, a government-subsidized housing scheme that had made about fifty homes available to poor weavers through lottery. We went to the house of Shaukatullah, a heavy, balding man, with thick-rimmed glasses through which he peered shortsightedly, a light-hearted, amused man, and a true patriarch. He himself had retired from weaving, though he was perfectly fit as far as I could make out and evidently seemed to prefer sitting in the sun, shouting at his grandchildren, and going to the market for every little thing. The weaving was done by his two sons and a hired hand, and after a cursory look at the workshop I was handed over to “the family.”

This was no small challenge for me to face. There were at least a dozen small children, half a dozen bigger ones, and as many adults. I settled down for the morning; in those days, so aware was I of my own limitations, I saw it as essential to give four hours where one was needed, recognizing that it was not only my informants’ natural reticence that had to be overcome but my own shyness and ignorance as well. In a household setting, I was particularly lost. As soon as I had an answer to one question, I would simply nod and look sympathetic, not quite sure how to follow up. Matters of child rearing and child care? No, that subject did not quite appeal to me. How did they cook and what did they eat? Mildly interesting, but not terribly so. What work did the women do? That was clear enough: every stage of nursing, feeding, teaching, cleaning up, getting bobbins ready, and sewing and embroidery besides was before me to observe. They, in fact, asked me more direct, meaningful questions. “Where is our brother-in-law? How many nieces and nephews do we have? What do they do when you go out to work?” I am ashamed now to report that I could not even understand in the beginning that they were asking about my family, having accepted me as a sister, so unversed was I in Banarasi, and Indian, conversational rules, but as their meaning dawned on me I rushed to take advantage of the opportunity to establish rapport. They had me all figured out by the end of the morning, whereas I needed another four visits to have their “case history.” In the process, through the familiar anthropological situation of role reversal, where they were the inquirers, I the object, they guided me in necessary ways. I paid close attention to their style of conversation, their Bhojpuri-Hindi lingo, topics that startled them and those they assumed to be natural, and I assimilated and adapted rapidly.

Three things dominated my impressions on that first visit. One was the fact of overpopulation and the related fact of filth. We sat in the courtyard, a cemented ten-foot-square space between the workroom, two family rooms, and the outer wall. All around it was a narrow open drain where the children were encouraged to pee, and at least one small child to defecate. Where the older ones relieved themselves I did not discover, then or ever. The rest of the courtyard was littered with spilled food, garbage, and what must have been urine. There were flies everywhere, and I was the only one conscious of them. I was determined not to let one alight on me, seeing as I could where it must have visited the minute before. When sweets were ordered and set before me on a freshly washed platter, I became engaged in a battle with the flies to keep them away and with myself to decide what best to do with these greasy sweets. Should I gobble them up before they could be further contaminated; refuse them with the excuse that I was unwell—“But these are made of chhena (cottage cheese); they’re good for you,” was the response I had learned to expect—; or distribute them among the children in a swift, decisive move. Incapable of the last, I nibbled and suffered, eating far more than I need have because I chose the disastrous course of saying that I could not tolerate much sugar and that tea and pan instead would be “just fine.” So, I ended up being plied with the sweets and deep-fried salty snacks—since tea could not be drunk after sweet but only after salt—and tea, with an extra layer of cream on top for my special enjoyment. The second impression, then, closely linked to the first, was of overbearing hospitality.

The third, by contrast, was the impression of perfect order, as I saw the rest of the rooms. The floors were bare, without furniture or objects, everything neatly folded and stored up on ledges, grain and other food in huge tin canisters, things of daily use in rows on shelves in the wall. Every woman knew her job, no child could touch or play with anything, and there was an obvious pride in housekeeping. “How beautiful!” I could not help exclaiming.

What kind of space was the courtyard then? It seemed that a bottle of quinine or some other household disinfectant was not beyond their budget but that they simply did not care. When I recollect that I did not mention those terribly unsanitary conditions in the middle of the house when I finally wrote my book, I wonder whether I cared either. Or rather, I forced myself to care less since I was helpless to do anything about it, and maybe that was true for the women as well. Perhaps there is a direct relationship between observation of certain problems and one’s ability to do anything about them, including report on them meaningfully. I remember one informant’s words, as I stood at the head of a repulsive, stenching lane and exclaimed, “This is impossible; this will have to be cleaned up!” “This will not get cleaned up, sister,” he replied mildly; “but your eyes will get used to it.” To write on the issues of filth and the indifference to it has been on my agenda from 1981, but I have been attending to easier tasks first.

At Shaukatullah’s I was for the very first time in the middle of a huge—blossoming, blooming, they would have said—family, as opposed to being among the men in their workplace or with one or two members in a specific context. I made it very clear that I did not want concrete information on this or that; I just wanted to get to know them, to become intimate with them, to get to understand them. There were three or four girls seated on the ground beside me, the older women moving in and out of the rooms as they minded the cooking and children alongside, the children all surrounding me and staring, being pushed away for touching me or my bag, and the men busy with their jobs. They were the ones I really wanted to catch, but they were too elusive. The oldest son, Majid, had ordered the refreshments and stood by me to supervise their consumption, and the father, who had nothing to do, still preferred to sit apart in the sun rather than to meddle in the women’s chatter, directing occasional sallies at me: “You want to know about Ansaris. Well, even among Ansaris there are many castes!” Or: “We start working from the age of ten or twelve. We really get to know life!” All of this was delivered in a teasing, bantering way. To make the most of a situation like this, one needed the skills of a politician, or at least the experience of someone used to addressing and controlling numbers of people together—a police station officer, a school principal, or even my mother on her large estate with her staff of sixteen.

I was acutely conscious of being in a Muslim household— not awkward or nervous but simply extra-sensitive to nuances of word and gesture, again an admission of my own ignorance. I felt I had an “in” on Muslims by virtue of my Lucknow background (distant but useful to evoke), thanks to which I spoke in a way that made all language-conscious Indians exclaim, “Your Urdu is so good!” My father’s oldest brother, my tauji, who lived in Lucknow, looked in his younger days like a maulvi, and he and his brothers had all been educated in Urdu, Arabic, and Persian in madrasas. Our Kayastha family was acculturated into “Muslim” ways of speech, dress, and civility from the days when “Hindu” and “Muslim” were not distinct cultural categories at all. In times of diffidence, tauji’s image comes to mind and I feel encouraged that I can be trusted to know how to act in Muslim company. I had never actually been put to the test. All these feelings of closeness to Muslims were vague ones. The Muslims I had actually known were either nonpersonalities like government bureaucrats or those otherwise neutralized by education and life-style. As a child, my closest friends were Muslims, Shani and Tashi, whose house I visited frequently. Their food was distinct, but then so was that of every Hindu family I knew. The main difference I remember is that in their home the grandmother used the spittoon, whereas in ours only the males did.

In Shaukatullah’s family, there was much to make a Hindu observer feel at ease. The women were dressed in the “rural,” or old-fashioned, style of sidha palla, the loose end of the sari being draped over their head and right shoulder. Their jewelry was rustic and their speech was predominantly Bhojpuri, the language spoken by every caste and community in Banaras. The terms and phrases I noted down from them and other such informants bore little resemblance to the Urdu originals, and for months I did not discover the precise reference for the less familiar ones. They used Hindu imagery freely, speaking, for example, of “Lakshmi departing from the house” to mean destitution or of “filling the parting with sindur” to refer to marriage—none of which was necessarily helpful, since I was not a typical “Hindu.” I was not a Hindu observer; I was simply a naive observer. The more closely someone fit a stereotype, the easier it probably would have been for me, but these people fit no stereotypes at all. Yet, upon reflection, the fact that we moved toward mutual acceptance so quickly surely had something to do with Shaukatullah’s simple notions of brotherhood and love between all and with my vague identification with Muslims from my family’s past.

The question of the “actual” and the “proper” feeling of Hindus and Muslims toward each other continued to haunt me throughout my fieldwork. I wished to discard all idealism or romanticism about this relationship and see it for what it was. Adopting an inductive procedure of the crudest kind, I observed every instance of interaction carefully and asked everyone with whom I had dealings what their reflections on the matter were—which were also then observations to be interpreted. I usually learned more about the person questioned than about Hindu-Muslim relations. One good example of this was the owner of a watch shop whom I happened to be interviewing on the same day I had talked at length with musicians and had realized how irrelevant religious categories were in the realm of music. This timepiece expert was a sort of aristocrat, a patron of the arts, avowedly fond of music, and of course from an old, established, and wealthy family of Banaras. He told me about contemporary organizations and the patronage of music. Toward the end of our conversation, I threw in carelessly, “And how would you describe Hindu-Muslim interaction?” “Sister,” said he in his quite memorable way, “as far as I know they are not interacting at all!”

In a matter of weeks I was given the status of a daughter of Shaukatullah. When I finally took my husband to meet my new family, a ripple went through the house: the son-in-law had made his first visit. My “parents” made a ritual farewell (vidai) that day, giving me a sari, blouse and petticoat piece, and sweets, and Sombabu a hundred rupees. To cover his embarrassment, he gave what I thought was a good line. “Why me?” he asked. “She is your daughter. Give it to her.”

9. Categories and Units of Observation

In November I started tabla lessons with Pandit Mahadev Mishra. I had already planned to do so in Chicago, thinking, like Ernie on Sesame Street, that I had rhythm in my bones but that vocal music would not be such a good idea, since I had given it a try for three years with mixed success. The lessons were for fun, of course, though with tabla I had the half-serious notion of giving my sitarist husband accompaniment to practice by. I also imagined that learning something would give me access to a musician, his family, and perhaps the whole community of musicians.

This was also around the time that I became determined to nail down those elusive quarries, kajli and chaiti. These were buzz words that you heard in all kinds of situations, and I gathered that they were names for two genres of folk music. Kajli (or kajri, the l and r being often interchangeable in colloquial Hindi) was the more familiar, being alluded to in sundry written sources as a genre popular with women, a phenomenon of the monsoons, an activity associated with swinging merrily on swings hung from sturdy branches. Only the second characteristic turned out to be relevant to Banaras. I had never actually heard either kind of music, nor did I know where I might. By that time, I was spending a fair amount of time in artisans’ homes, was very close to some informants and developing other relationships further, increasing my circle of acquaintances steadily. But to know them or to visit their homes was not necessarily to discover their music—as it was also not to discover their gymnasiums, the akharas, or their picnics, the going out to bahri alang.

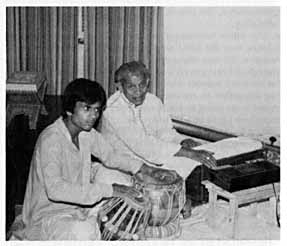

My other informants were bad, but Pandit Mahadev Mishra was the very worst informant a researcher could imagine. He was imprecise, did not believe in fact or detail, thought it boring to stick to a subject for more than a minute, let his mind wander where it would, and often stopped talking altogether to reminisce and smile privately to himself (see fig. 6). Apart from going to his house thrice a week, I also liked to bring him home on a Saturday, partly to offer him hospitality. That evening in November, as we were sitting at the tea table, the electricity went off for a long time. We sat in the dark and talked. He was relaxed and seemed pleased with the atmosphere. Pressing him gently, I asked for the umpteenth time, “Tell me about this Banarasi kajli and chaiti.” He did not, for once, brush my question aside as irrelevant—either you know it in song or you don’t; what is there to say about it? In fact, he did, in a way, because instead of saying anything, he sang some examples for me. I couldn’t recognize or differentiate them for my life. Then he told me, in one of those rare inspirations of his that always meant a major breakthrough for me, “I’ll take you to a disciple of mine. He’ll tell you all about kajli.” I promptly fixed time and place.

Pandit Mahadev Mishra singing the Ramayana

Pandit Mahadev Mishra was old even then, though it was difficult to remember that he was in his mid-seventies. He leaned heavily on his cane and walked slowly, but he was braver than I—as is every Banarasi—in trafficking a gali about three yards wide fully occupied by a fierce black buffalo. We reached the long, extended side of a one-storied house with many doors, and he called out for his disciples. There were two brothers, Dadu (Kshamanath) and Santosh Kumar, to whom I was introduced. I promised to return the next day.

Dadu and Santosh were tailors, urbane and mild-mannered young men, reserved and refined. They had both learned a little from Mahadev Mishra and had natural talent. Their father was an amateur poet and composer and so were they. To my eye they looked westernized, with their bell-bottomed trousers and styled shirts, but then I recalled that so had Gauri and Kishan at Vishwakarma Puja, and every other young man I had met outside his workplace or the courtyard of his home. There was in fact no question about any of these men being westernized. They were quite the opposite. The clothes they wore were part of Banaras and did not signal westernization to local people as they did to me. Dadu and Santosh quizzed me for hours about my purposes, and even then I had not awakened a sympathetic gleam in the eye or earned a nod of the head from them. We sat there cementing our relationship, chatting about Chicago, old and new times, coming back to how great a musician Mahadev Mishra was as a kind of refrain. With the sheer passage of time, I became a familiar sight at least. When they sent out for sweets and persuaded me to eat up, I thought I had become accepted. But I was no closer to discovering the meaning of chaiti and kajli.

When they did start talking about the music, I realized that there was something wrong with my phrasing of the question. No one can tell you “what” chaiti or kajli is. They would not even agree that it was “folk music” and complicated the whole issue further by telling me of half a dozen other forms that were “actually” folk music—chhaparya, purbi, bhojpuri, biraha, qawwali, ghazal—and labeling them in passing as “uncultured” and “of poor taste.” They did tell me of music akharas (“clubs”), however, of their famous leaders, and of their father’s akhara, called Jahangir. And they invited me to their Monday evening get-together in a room opposite the Hanuman temple in Khari Kuan, a few yards from where they lived.

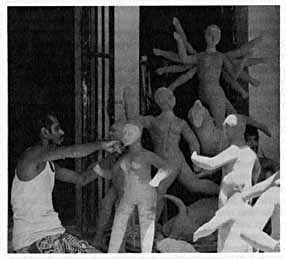

I went the next Monday, entering after the singing had begun, and was mesmerized. It was dramatic, exciting, emotional, and very, very charming. The room, about ten feet square, was bare except for an open Ramayana, a garland, and an incense stick next to it. Two main singers faced the book, and the dozen or so other men in the room were divided roughly into two groups, one on either side. Each leader had a harmonium, a lanky and short-cropped fellow had the dholak, the two-sided drum, and the rest had cymbals (see fig. 7). I entered in the middle of a loud, uncontrolled burst of singing, exposing a dozen pan-red mouths.

An informal folk music gathering with Brij Mohan, a wooden toymaker and dholak player on the right

It was the first time that I had heard live folk music close up and in the very making, and the new experience contributed to the excitement. But far more exciting was the countenance and emotion of the singers themselves, their eyes closed, their bodies swaying, their voices eager to follow the lead pitch. That Monday turned out to be the first stop in a long odyssey which took me to byways and alleys, basements and rooftops, teashops in busy lanes and even temples on hilltops outside the city, all to hear and record this music. I began comprehending what chaiti and kajli and holi were and appreciating the fine distinctions within each. Finally came a time when I felt that I knew what Mahadev Mishra had been talking about when he had said to me, “Chaiti makes the hearts of Banarasis skip and beat with excitement,” but, in all honesty, this understanding came much later, when I was back in Chicago, my headphones glued to my ears. I understood biraha less, then and now, and certainly enjoy it far less. I discovered, totally out of the blue, the other genres of khamsa, ghazal, and Ramayana (as they used the term, to designate both book and genre). The mildest thing I can say about it all was that it was never boring. Even when the tunefulness was not impressive, the circumstances certainly were. On one occasion, piles of little hand-crafted brass and copper vessels, called lotas, were piled against a wall as the two teams chorused under this gleaming backdrop. On another, a still summer rooftop was filled with woodworkers and their families from all the surrounding lanes of Khojwa to hear Mohan the pan-seller sing and Brij Mohan, the same close-cropped young latheworker I saw in my first encounter, play the dholak. In yet another instance, I was placed on a bench over a drain facing a tea-shop transformed into a clean baithaka where panwallas and chaiwallas (pan and tea sellers) congregated. Always at ten or eleven at the earliest, always too late to make my pleasure unadulterated.

I felt little surprise upon discovering how dedicated and talented so many of my brass worker, coppersmith, carpenter, and toymaker informants and their peers were. I was getting used to this cultivation of excellence by seemingly unremarkable people. Strange to say,until this time I had heard the poor spoken of at best with pity and condescension, but never with respect. Their varied interests and their attitude toward life as something to be lived to the full were my discoveries in the field. I was perhaps quietly testing to see at which rung of the economic ladder this independence and spirit ended, and beneath which were only helplessness, suffering, and subsistence, where the frail structures built by the mind, so to speak, started relating one-on-one with physical impoverishment. I rested the case (with respect and gratitude) the day I visited a rickshawalla through the agency of his artisan son. Expecting a wretched hovel, I was stunned to meet this dignified widower leading a meticulously planned existence, obviously rich in the middle of his absolute poverty, his spare time devoted to musical renditions of the Ramayana.

How I organized my late-night trips to musical performances is a matter of wonder to me today, because I don’t think I now have the energy, enterprise, and sheer daring to chase things thus to their end. I had to find escorts, of course. Coming back would be no problem, I was always assured; one of the singers could be persuaded to see me home. But to go at ten or eleven, or even at midnight, very likely to cold, dark, sleeping neighborhoods, usually by roads and lanes only halfway decent even by the light of day—all this needed determination. I formed, over the months, a platoon of “brothers,” young men like Markande the stoneworker, or Nagendra, clerk in an unknown office, who were themselves totally uninterested in the events I proposed to witness but who, having declared themselves my brothers, could not say no to me. So the person in question would bundle himself up, find me a rickshaw, and then cycle along to the destination. I would not let him go, and he had to sit, or slouch, or sleep, or whatever he could allow himself to do, till I was ready to leave. I should add that I was always conscious of my high-handedness and cut my visits to music gatherings shorter than they would have been had I been on my own.

I was always the only woman on the scene at the regular gatherings; the exceptions were the annual celebrations of shrines, called sringars, and special programs, such as the one on the Khojwa rooftop, when women and children formed the outer rings of the audience or made themselves comfortable on adjoining rooftops. I do not remember ever minding my solitude or suffering any discomfort from it. Either people ignored me—though they did not ignore my tape recorder, treating it gently and reverently as it was “filled up”—or they treated me with respect and protectiveness. “A chair, a chair! Get a chair!” was one way of expressing this, though no chair would appear out of the darkness. There was no teasing, bantering, joking, or even questioning. I think the assumption was that of course their music was special enough for me to come a great distance, leaving family and home, to hear and record it. I had not known of this great music for many reasons; my informants uniformly put it down to India’s regional diversity. Native Banarasis clearly understood that “Indian” is a term needing qualification. They matter-of-factly attributed my ignorance to my origins at variously conceptualized points lying in westerly directions. In their more euphoric moments, I was often flattered by informants: “It’s really miraculous, how you can come from outside and understand the music [or whatever other thing at the moment it was] of this city”— where “outside” for them meant not Chicago or New York but Lucknow.

10. Among the Police and Administration

I have neglected to mention my ethnographic adventures at the beginning of our stay, when we got to meet the high society of Banaras. Within our first week we went for dinner to Mr. Rishi Pratap Singh, a prominent businessman; for dinner to the Senior Superintendent of Police; and for lunch to the Superintendent of Police, Intelligence. The first was a family friend of many years’ standing, the second a subordinate of my father’s, a lively and likable person who had worked hard to help find us a house, and the third was the husband of an old school friend I had met again after many years. The reason for all these social gatherings was the transfer of the District Magistrate, the kind of event that occasioned farewell parties. The dinners took place after midnight, the lunch at only 4 p. m., all preceded by long hours of formalities, high-flown declarations of friendship, and very poor jokes. The food was the most elaborate conceivable, unbeatably expensive, and lavish, with almost every delicacy that was available in the market served at the meal. There was always soup for starters. Now if I were to serve soup with Indian food, I might hope that it would fill people up a little and make my food go further. But the guests needed no such consideration; there was always one vegetarian and one nonvegetarian table laden with dishes, and the hostess circulating: “Bhai Sahab! Bhabhiji! (Brother! Sister-in-law!) You are not eating anything!”

We were alternately revolted and saddened by it all: the poverty of taste, the vacuum of interests and purposes, the wastefulness and underlying degeneration. Yet we went to every one of these functions, without ever feeling kinder toward this society, because I reasoned to myself that my curiosity about it all could be satisfied only by personal participation. We also found it difficult to say no and could never think of satisfactory excuses in time. Yet each degrading experience made us despise ourselves for attending and resolve never to do so again.

I had perhaps an easier time of it than I could have had, because I was not obliged to sit in the drawing room in a row of ladies, enduring the jovial pressure to “finish my drink.” With the excuse of a little baby, I could retire to a quieter room to nurse Irfana, put her to sleep, or sit with her. At the Singhs’ house, the youngest daughter, Meena, was doing her lessons in the room I retreated to. She was learning by rote answers to certain questions for her General Knowledge test on the morrow. “What are stockings?” she kept asking restlessly. The subject, apparently, was festivals, and the question was “What happens at Christmas?” In that warm bedroom draped with mosquito nets, I concluded there was little connection between children’s curriculum and the social or historical reality around them. As for the problem of the language itself, Meena did not need to have trouble with “commemorate” for me to feel that there was no connection between the medium she was learning in, English, and her consciousness.

At the S.S.P.’s house, our hosts were so thoughtful as to arrange for a woman to watch our baby during the party, the wife of one of the servants, who came in occasionally to massage the mistress, help out with guests, and so on. I was delighted to have a person to talk to. Finding out about her was simple enough, but when I learned that she was a Banarasi, I grew more ambitious. “There was this Burhva Mangal mela that was held in Banaras years ago,” I told her in a confidential tone. “Tell me about the Burhva Mangal fair.” She absolutely denied any knowledge of the fair, as if the confession would jeopardize her in some way, and, shutting up altogether, sat in a bundle, probably tired and dozing. I was nonplused. Everyone else seemed to know of the fair. Was she too young? Had she been too secluded? Was she a moron? The meeting pricked in my mind as an unresolved riddle until I decided, after other similar encounters, that it was impossible to turn servants into informants. Or, for that matter, informants into servants.

I had occasion about a year later to use an informant in a serving capacity, with the idea of helping her out and saving her from worse drudgery in uncaring homes. What I discovered was this: the master-servant relationship could not be reconciled with the empathy and closing of distances aimed at in fieldwork. Once you were familiar with another’s values concerning food, spatial and temporal preferences, and devices for maintaining individuality and freedom, you could not, without considerable agonizing, order the person to conform to a different set of values. But you had to do so as a master, and indeed to condemn these very freedom-preserving devices as lazy, dishonest tricks. My quarrels with my informant-turned-servant were about things as petty as teamaking. Being perfectly attuned to the sweet, cooked tea served all over Banaras, I proceeded now to dictate the terms under which tea could be made in our home: always in a teapot with a tea cozy, leaves steeped in freshly boiling water, milk and sugar on the side, and so on. Nor could I stand it if my new maidservant brought anything preserved on a platter, in ordinary Banaras style. The very same habits I accepted as rational, legitimate features of another life-style were intolerable in my own home: it was oppressive to be made to eat and drink in ways not of my choosing under my own roof.

My poor ex-informant could not fathom the dilemma and proceeded as cheerfully as ever to supply me data regarding Banaras customs through her behavior. For example, she habitually took a couple of days off for any festival, major or minor. I knew perfectly well about the leisurely pace of Banarasis, their lightheartedness and love of holiday celebrations. But when victimized (as I saw it) by these otherwise admired characteristics, I threw a tantrum: “How can another person (me) work if the first doesn’t stick to the rules? Don’t you have a modicum of responsibility toward the task you are committed to?” and so on. Thus addressed, my subject sulked, suffered, and degenerated into a still more imperfect servant and informant. This was during my first stay in Banaras; in later visits over the years I had the good fortune (it would seem) to be in close daily contact through domestic service with men and women from weaving, woodworking, stoneworking, carpenter, biri (cigarette) making, and rickshawalla families. I learned to close my eyes to their occupational backgrounds and cultures and to acknowledge that the roles of servant and informant were not complementary. But my first round of fieldwork had such a long-term formative influence on me that I was doomed to have only inefficient control over my servants ever after that.

To return to the high society of Banaras, I was constantly trying to calculate whether the officials we supposedly knew were of any use to us at all or whether they were leading us up blind alleys all the time. They seemed utterly sincere when they promised help, as they did at the drop of a hat. Yet their offers for housing, gas, service people, introductions to informants, and shots for our child had only delayed us, and finally we obtained everything without their help. Sometimes we had actually suffered from their help, as when, through their mediation, we would meet a musician or other important person who would prefer to ignore us, classifying us as members of a despised officialdom. Then we would make an entirely new approach, in our own capacity, and woo the individual back to a neutral stance regarding us. The outstanding case was the tabla player Kishan Maharaj; he became so incensed at what he imagined were arrogant demands on our part to come and play in our house that he threatened to write about it to a local daily. We had a showdown and developed an excellent relationship after that. Most people in India, even when they pretend to be allies of the administration, harbor a deep and just distrust of officials; simple people like my artisans do not even need to pretend. If one appears on the administration’s side in class or status then one suffers the same distrust automatically. So, for us the job was clear-cut: disassociate ourselves from the rulers, not only because it made sense culturally but because it was a pragmatic research need.

In some matters, however, our police contacts were fortunate. As soon as I would ask about a particularly crowded mela or celebration, a jeep would be offered. Sometimes the offer would materialize and sometimes not. One did appear, at least, to take me to the Ramnagar Ramlila in Sombabu’s absence and to show me the Durga Pujas around the city. The immersion of the Durgas in the river the next day, a festival in its own right, was happily planned for me by the S.S.P.’s wife. My name was added to the guest list of a motor launch fitted out for Banaras VIPs, and we chugged up and down the ghats in the dusk for two hours. All the ghats were silent, dark, and primitive, except for Manikarnika, bright with funeral pyres, and Dasashwamedh, a sea of figures, where the Bharat Sewa Sangh sadhus (monks) were dancing before radiant images. I would never have guessed what it was like had I not seen it, and seen it from the boat, because I would never have found a place in the dense crowd on the ghat. The following year I used my contacts again. The police had a camp on the highest point of Dasashwamedh ghat, and with little Irfana I sat in the best spot on the promontory the whole evening, both of us soaking up the spectacle of various-sized boats carrying their Durgas out and unloading them into the river. All other immersions—Kali, Vishwakarma, Ganesh, and Moharram—I have witnessed from yet other perspectives, and I readily admit that police help has been unnecessary for them.

The first day that Sombabu was away for a prolonged time, the inspectors (station officers) of Bhelupura and Maduadih thanas visited me in quick succession to offer their assistance in my time of solitude. They could not have guessed how desirous I was to meet police inspectors in Banaras. An inspector seemed to me, before I learned differently, to hold the key to what goes on in his circle (his kshetra) and to be eminently interviewable regarding the crimes, events, persons, and general character of the area he is in charge of—a living document, as it were, a nicely detailed administration report of the present that you could cross-examine. My plans for interviews were never realized. There was always something more immediate to ask of the inspectors when I could meet them. That in itself was not easy, as my repeated visits to Bhelupura thana proved to me: the man would always be out on “tour” or unavailable for unspecified reasons. I suspected that as I grew less novel and more familiar, and also less impressive, perhaps even ludicrous because of my childish interest in ordinary, daily, common things, the inspectors concluded that it was not worthwhile to pay attention to me. On my part, I came to realize that there were people far more knowledgeable than police inspectors to interview, even regarding a kshetra, and I no longer found time to chase them. I had made some advances to likely individuals, such as the Circle Officer II, who sat in the Dasashwamedh thana, but none of them—neither he nor other officers, not even the husband of my old school friend—ever responded to my gestures of friendship. The one exception was Krishna Chandra Tripathi, but his motives were not above suspicion, as I shall shortly describe.