PART THREE

THE DANCE OF SYMBOLS

Chapter Twelve

The Civic Ballet: Annual Time and the Festival Cycles

Introduction

To bring Bhaktapur's symbolic order to coordinated life, a temporal system and a patterning of events within the tempos of that system are necessary. There are in Bhaktapur two large classes of symbolic enactments that tie together public space, individuals, social units, deities, and time into a larger assemblage. In these enactments, the various matters that we have dealt with in earlier chapters become elements in a civic performance . Social roles, significant space, the complexes of meaning represented by deities, priests, and modes of worship emerge and become realized m these performances, which, like their constituent aspects, follow traditional patterns. The first class of these civically significant enactments are the rites of passage, the samskara s (app. 6), whose sequence is determined—often with considerable leeway in their exact timing—by the stages of the life cycle, fine-tuned through astrological considerations. In Bhaktapur these rites entail references beyond the individual and household to the patrilineal extended family, the phuki , and beyond that to some larger civic units (primarily the twa : and the mandalic[*] area pitha ). But the samskara s’ central importance is in defining the individual in relation to household, extended family, and, with marriage, to an allied kin group within his or her status level. Their relation to the larger city is secondary, and for the most part simply emphasizes the phuki ’s relation to neighborhood and Mandalic[*] Segment, as all phuki worship does. It is the second class of temporally

coordinated ritual enactments that are the true civic enactments. That group is primarily constituted by those activities that take place in the city following the dictates of the calendar. These include practices that are appropriate—in many cases necessary—for particular days of the week, of the lunar fortnights or of the solar month. However, at the center of our concern in this study are those events whose occurrence depends on the annual cycle itself. This particular temporal set, the yearly events, has special urban emphases and uses in contrast to the smaller and larger cycles.[1]

Many of these annual events are associated with feasts encompassing one or another social unit, and are designated as nakha cakha (Kathmandu Newari, nakha: cakha: ), literally "to feed and associated activities."[2] "Nakha cakha " may be glossed with appropriateness by "festival," with that word's connections to "feast" and "festive." The term "festival" also works well for some of the other major and public events of the year, particularly if "festival" is extended to include some restrained, minor, or routine "celebrations." However, there are other significant annual events—a day for the protective rubbing of bodies with oil, a day on which the moon should not be viewed, and so on—for which the term is inappropriate. Hindu calendrically determined events include two sorts of events that, although distinguished by classical terminology, are blurred in actual usage. These are vrata events and utsava events. "Vrata " implies a "religious duty," and is used often in Bhaktapur in the strong sense of "religious or ascetic observance taken upon oneself, austerity, vow, rule, holy work such as fasting and continence" (Macdonell 1974, 304). The other term, "utsava, " indicates, traditionally, "festival or holiday." Gnanambal, in a report on surveys of Indian "festivals," notes that the term "vrata " has a wider usage in many parts of India to include "festivals," especially where fasting is a necessary element (Gnanambal 1967). There is, nevertheless, in usage, he adds, a "faint distinction" of vrata and utsava as evidenced by the presence of the two terms in many parts of India. Kane (1968-1977, vol. V, p. 57) also remarks on the difficulty of using the termino-logical distinction for discriminating actual events.

The annual events we will consider contain among them elements of vrata and utsava and sometimes of neither, and we will use various glosses for them, all meaning no more than "calendrically determined event of general civic importance." During the course of the year in Bhaktapur there are some seventy-nine of these, and as on some days there are more than one and as, in contrast, a few last for two days,

there are a total of seventy-four days each year during which some part or all of the city is involved in one or another such event. This is in addition to weekly and monthly activities during the course of the year, as well as the pilgrimages and mela s or "fairs," taking place elsewhere in the Valley (or beyond) every year or every few years in which people in Bhaktapur may participate.[3] These gross enumerations are, however, misleading as our discussions in later chapters and a more refined enumeration in chapter 16 will indicate. Later chapters will provide a clearer view of the types and density of calendrical events in Bhaktapur.

The calendrical events, derived from South Asian tradition and the Kathmandu Valley's long history, are, like the supernatural members of the city's pantheon, of interest to us primarily not as a collection of witnesses to that history but as aspects of an ongoing, meaningful contemporary urban life. We will say something, if only in passing, about each calendrical event, but we will treat certain events at much greater length, and among these we will be most particularly concerned with what we call the "Devi cycle" and its climaxes in Mohani, the Autumn Harvest festival sequence, and in the related performances throughout nine months of the year of the Nine Durgas troupe. The events we emphasize are, evidently, those we take to be of particular integrative importance.

The Calendar

Bhaktapur, typically of South Asia, has both a solar annual calendar and a lunar one.[4] While the great majority of festivals are determined by the lunar calendar, there is one major festival sequence (Biska:, the solar New Year sequence) and one other annual event which are determined by the solar cycle. The lunar year is normally divided into twelve lunar months. The lunar month begins on the day following the new or dark moon, which ends the previous month.[5] The Newar lunar month is divided into a first "bright" half, corresponding to the waxing of the moon, and ending with the full moon; and a second "dark" half, corresponding to the waning phase of the moon and ending with the new moon. The bright fortnight is called tumla ; the dark fortnight, khimla .[6] To designate individual lunar fortnights, terms for the dark half and light half of the lunar month—ga and thwa , respectively—are added to the name for the particular month. The name of the month is itself a compound including the morpheme la , meaning lunar month. Thus the

TABLE 2 LUNAR FORTNIGHTS | ||

Month | Newari | Sanskrit |

October/November | Kachalathwa | Kartika |

November | Kachalaga | |

November/December | Thi(n)lathwa | Marga |

December | Thi(n)laga | |

December/January | Pohelathwa | Pausa |

January | Pohelaga | |

January/February | Sillathwa | Magha |

February | Sillaga | |

February/March | Cillathwa | Phalguna |

March | Cillaga | |

March/April | Caulathwa | Caitra |

April | Caulaga | |

April/May | Bachalathwa | Vaisakha |

May | Bachalaga | |

May/June | Tachalathwa | Jyestha[*] |

June | Tachalaga | |

June/July | Dillathwa | Asadha |

July | Dillaga | |

July/August | Gu(n)lathwa | Sravana[*] |

August | Gu(n)laga | |

August/September | Ya(n)lathwa | Bhadra |

September | Ya(n)laga | |

September/October | Kaulathwa | Asvma |

October | Kaulaga | |

"Thwa " is the waxing fortnight, ending with the full moon. "Ga" designates the waning fortnight, ending with the new moon. | ||

first lunar fortnight of the lunar year, Kachalathwa, means the bright or waxing fortnight (thwa ) of the lunar month (la ) of Kacha, which is followed by Kachalalaga, the dark fortnight (ga ) of the month of Kacha. Table 2 lists Bhaktapur's lunar fortnights, the Sanskritic equivalent months, and the approximate correspondences of the fortnights to the Western year. The table does not include the intercalary period, which has to be added every third year to adjust the lunar to the solar year, and which does not usually affect the ritual calendar.

The full-moon day, which ends the bright lunar fortnight (the first half of the month), is called punhi , and the dark or new-moon day, which ends the dark fortnight is called amai[7] The other days of each lunar fortnight are given ordinal numeric Sanskritic names, with the

exception of the fourteenth day of the dark fortnight, whose Sanskrit name, caturdasi , is usually replaced by the Newari term "ca:re ". The lunar days are called tithi . Although they vary in length (from about 21.5 to 26 hours), they are, for most purposes, made to correspond to ordinary solar days.

The solar year, which is of very much lesser importance for the ritual cycle, contains twelve months. The names of these months are the same as for the Lunar months,[8] although there is, perhaps, a tendency to use the Sanskritic forms more for them. The days of the solar year, gate , begin at sunrise. They are arranged in a seven-day week deriving, as the solar calendar in general does, from the same sources thus sharing some of the same astral references as the Western days of the week. The occasional necessity of relating the solar and lunar years requires a complicated set of rectifying conventions that are not relevant here.

Approaches to Meaning

In the next three chapters (chaps. 13 to 15) we will describe the annual calendrical events. We will look for aspects of form and thematic content, and for similarities and contrasts that contribute to the meaning-fulness of clusters of and subcycles of calendrical events, as well as of the entire annual collection. We will introduce here some of the issues and approaches that will concern us in our detailed presentation of the festival year.

Cycles

There are many ways of sorting Bhaktapur's calendrical events. Our first rough sorting has been into events of the solar year and of the lunar year, and then a further division of the lunar year into one set that constitutes a clearly interrelated and extremely important group, the "Devi cycle," and another, residual, lunar group. The solar calendar has only one important festival sequence, Biska:. The lunar cycle as a whole (as opposed to the clearly integrated Devi cycle) seems on the surface at least to be a mixture of miscellaneous events. We will, however, be concerned with its deeper patterns insofar as they may—or may not—exist.

Marc Gaborieau (1982) has proposed a "structure" for the Indo-Nepalese calendar that, although problematic for the Newars at least,

provides a useful point of departure for a discussion of the meaning of the overall lunar cycle. He notes that some writings on Hindu time (he cites Mus [1932-1934] and Zimmer [1951]) represent it as having the following properties: (1) each of the different divisions of time (days, years, cosmic periods, etc.) is arranged in a cycle; (2) these cycles are formally similar; (3) each cycle has a beginning and an end; (4) each cycle has a movement from order toward disorder and culminates in a state of chaos that precedes the regeneration, which will mark the beginning of a new cycle; and (5) the stages of chaos and regeneration are not considered parts of the temporal cycle, but temporary escapes from time. They represent the "axis which communicates with eternity."

Gaborieau argues that this schema is reflected in the Indo-Nepalese festival cycle. For the Indo-Nepalis, he writes, the four-month period beginning with the summer solstice—the period of the monsoon and the major work prior to the rice harvest—are considered inauspicious months, but it is also the period for the majority of the year's festivals. The period begins with the festival of Hari Sayani, the time when Visnu[*] goes to sleep for a period of four months "leaving the earth to the demons." In Gaborieau's speculation, those months are out-of-ordinary secular time. The first two months correspond to the period of disorder, the second to the period of "regeneration." The festivals during this period "manifest radical disorders and reversals followed by profound restorations of order" (1982, 16). In contrast, he argues, the eight-month period beginning with the first winter month (Marga in November/December) is an auspicious period where life follows its normal course, and household ceremonies for good luck, and prosperity, and the like, take place as do lineage ceremonies. He further argues that those inauspicious events, the disorders and reversals, that do take place during this period primarily concern the lower castes. The "cyclical mystery" of the year as expressed in its festivals is the privileged experience of the upper, twice born castes.

How far this schema is adequate for the sorting of the Indo-Nepalese festival calendar is for others to judge; the involution of festival practices, the relative secularization of most of the Indo-Nepalese groups, will make an anthropological critique difficult. In its details, this schema does not work for Bhaktapur's calendar, but for certain aspects of that calendar and with different timings, it will provide (in chap. 16) a useful point of departure for an analysis of the possible implications of the arrangement of all the components of the annual cycle within that cycle.

Whatever the internal structure of the overall annual calendar of events may be, there is the partially related question of how the meanings of the events might be affected by external cyclical events of a different order. Is there any relation of the meanings of festival events to the phases of the moon and to the sun's course and seasons beyond their clock-like uses in coordinating the cycle? The kinds of data we deal with show only scanty echoes of these cosmic events. But when we consider still another external cycle (in turn, dependent on the seasons), the rice agricultural cycle, particularly in its relation to the Devi cycle, the connections are of central importance.

Selection from the Hindu Set of Festivals

Although most of the elements of Newar symbolic life are taken from the inventions and developments of South Asian history—supplemented by some significant bur quantitatively minor Newar and Himalayan forms—there is, as we have seen in relation to the urban pantheon, a necessary selection among these elements. There are quantitative considerations—only a certain number of elements can be understood and put to use in the civic system. There are also considerations of propriety; some forms do not fit in, or are redundant, have their places filled, as it were, by other symbolic elements. As is the case with all inventories of South Asian possibilities, the list of calendrically anchored events noted in the classical literature and religious texts is very large. Kane has what is presumably an almost exhaustive list of calendrical vratas and utsava containing well over one thousand events throughout India's vast history and extent (1968-1977, vol. V, pp. 253-462). These vary in their general importance and occurrence through out historic time, space, or class of devotees.[9]

Bhaktapur's calendar selects and rejects from this group, and invents—or often pieces together from existing fragments—its own festivals. The most salient contrast of the Bhaktapur calendar for Bhaktapur's citizens is with other Newar calendars and with Indo-Nepalese calendars. Not only does the presence or absence of calendrical events in Bhaktapur reflect an active selective in relation to other calendars, but so, and often more significantly, does their local importance. Thus a festival of general South Asian importance may be present in Bhaktapur, but only in some residual and unimportant manifestation. We will consider the questions of selection and emphasis in the following chapters.

Aspects of the Analysis of Calendrical Events

When we narrow our horizon to look at Bhaktapur's various calendrical events in themselves and in their similarities and contrasts to each other, we must seek appropriate and relevant aspects for analysis and contrast. We must attend to the social and spatial units involved. What are the static and dynamic uses of those units? Which deities are made use of? Is the deity or deities moved; do people move? Where? To what purpose? Who are the human actors and audiences? What are the different sorts of actions? What are the themes and narratives portrayed and recounted? Are there narrative "plots," with conflicts, tensions, climaxes, resolutions? What kinds of symbolic forms and rhetoric are used to contribute to meaning? What kinds of themes are there in various events? What problems seem to be dealt with? How do participants seem not only to act in but also to respond to particular calendrical events? How are various city units tied together—through "parallel" devices (with various units doing the same sorts of things at the same time) or through "serial" or "interactive" devices, with some sort of meaningful movements and encounters systematically interrelating different kinds of actors and social units in the course of the event?

Such questions are in the background of our considerations of calendrical events, but we have not dealt with these issues explicitly in relation to all the calendrical events noted in the following chapters, for many minor festivals many of them are irrelevant. These various elements of festival meaning become fully relevant only in the more developed festivals, those that are more important to Bhaktapur by various criteria, which we will present in the following chapters.

A catalogue of their potential resources for generating and expressing order and meaning, in fact, is liable to make the annual events seem more exhaustively integrative and constitutive of the city's symbolic system than they really are. That task falls on selected ones. The question of which potential resources are, in fact, used or neglected by particular individual events and throughout the course of the annual cycle is an empirical one.

We will see that the events vary in importance from "trivial" to what we call "focal" events, events of central importance to the city,[10] and we will make an estimate of the relative importance of the various calendrical events as being of minor, moderate, or major importance. In the next three chapters we will lose ourselves among the trees of the annual cycle. In chapter 16 we will return to the view of the forest, and

the consideration of its differential contributions to urban order. What do these annual events do for Bhaktapur and its people? How do they do whatever it is that they do?

The Inclusion and Sequential Numbering of Calendrically Determined Events

Some arbitrary decisions regarding two issues were necessary. First, when is a day of the year that is given a particular name really to be considered an event of some civic importance and thus to be listed? In some cases, for example, a particular full-moon day, the day may be given a special differentiating name, but the activities characterizing it are no different than for other such days, the day being an unexceptional member of the, for the most part, internally undifferentiated set of twelve full-moon days. A particular day may have some special differentiating feature of very minor present importance, or be of interest in only a personal and optional way to some few individuals or households, or to some particular thar . It has been optional in some few cases whether to include or exclude an event; we have usually (but not consistently) excluded it unless there is some clear suggestion of civic importance according to our criteria. The minor processions of certain deities that we include and list among the "minor" festivals are also of very marginal importance, in this case because they have little or no present following or attendance—but they are clearly public urban events dictated by the calendar, echoes sometimes of events of some past importance and possible nuclei, in some interesting cases, for some future efflorescence.

A second problem is how to distinguish separate events for enumeration within some larger festival sequential complex, such as the autumn Mohani festival or the solar Biska:. We have dealt with this in somewhat different ways in those two cases, in large part following local conventions.

In should be noted that the sequential numbers that we use to designate festivals in the following chapters are derived from the sequence of the entire group of annual festivals starting with the lunar New Year's Day. Thus the numbering of the events in the three individual cycles indicate their position in the overall annual collection of events. (The annual festival calendar is given in summary form in app. 5.)

Chapter Thirteen

The Events of the Lunar Year

Introduction

The great majority of the annual events in Bhaktapur's yearly collection of calendrically determined events are determined by the lunar calendar. The sequence of these events constitutes a cycle in the dictionary sense of "a period in which a certain round of events or phenomena is completed, recurring in the same order in equal succeeding periods." So defined, the solar events form a cycle of their own, as their position within the lunar sequence varies from year to year. Do the events of the lunar year form a cycle in the literary sense of a group of poems, myths, tales, and the like with a common theme and, perhaps, some integrated structure? Quests for an overall structure of the events of the lunar year—such as Gaborieau's (1952), which we discussed in the previous chapter—suppose that they do form a cycle in this latter sense. One group of lunar events—which we call the "Devi cycle"—is of major and central importance to Bhaktapur precisely as a clearly integrated annual thematic cycle, taking much of its meaning and tempo from the cycle of rice agriculture, and carrying some of the most powerful "messages" in support (as we shall argue) of the symbolic integration of the city, and we have isolated it for extensive treatment in a later chapter. In the present chapter we will note when the events of the Devi cycle take place, but will defer their discussion. We may expect that some of the residual events of the lunar cycle with their historically determined calendrical position may have relatively isolated signifi-

cance. Others are related to each other and the larger cycle as smaller thematic groupings or, more significantly, in terms of formal similarities and contrasts, expressing some kind of structure or rhythm within the year.

In the chapters on calendrical events we face the problem of what to present about particular events. Any major calendrical event would in itself require special studies and a volume to describe and interpret it in something like full detail. We will present in this and the following two chapters the details necessary for the purposes of our arguments about Bhaktapur's civic religion, swollen by occasional additional ethnographic description, particularly in those events that are either unique to Bhaktapur or of special importance there.

The numbers given in brackets following the names of individual events in the next three chapters indicate the sequence of the events in the entire annual calendar. The solar events are numbered according to their position within the lunar calendar of 1973/76. Although this chapter discusses only those events of the lunar year aside from the Devi cycle, all lunar and solar events are noted in this chapter to take account of the overall collection of events (see also app. 5).

Swanti and the Lunar New Year [77, 78, 79, 1, 2]

It is the lunar New Year's Day[1] that begins the fundamental year—the sequence of lunar months, the basic calendar within which the solar events are variously located from year to year. As P. V. Kane writes, the lunar New Year "in ancient times . . . began in different months in different countries [in South Asia] and for different purposes" (1968-1977, vol. V, p. 569). At present the lunar year begins in India, for the most part, in Caitra (March/April) or Kartika (October/November). The Indo-Nepalese year begins in Caitra. The Newar lunar year begins in Kartika, a time which, in its contrast to the Indo-Nepalese New Year, is considered in Bhaktapur to be a distinctively Newar practice, and with an event, Mha Puja [1], which is considered to be a uniquely Newar event. The New Year's Day falls on the fourth day of a five-day set of events called "Swanti."

Although "Swanti" refers to the five-day sequence, it is said to be derived from swanhi , "three days," that is, the last three days of the sequence—the day before the new year, the New Year's Day and the

succeeding day.[2] Alternative scholarly names, such as Pa(n)carata, referring to the entire five days, are much less used. The festival is related to and derived from the South Asian Laksmi festival, Divali or Dipavali (the "Festival of lights"), a festival that is also associated with the lunar New Year in some other parts of South Asia such as Gujarat, where the lunar New Year is "inseparable from and part of the Diva1i celebrations" (Gnanambal 1967, 6).

The five days of Swanti are characterized by a unity of themes and significant forms. They emphasize in both form and in theme the existence and importance of relations within the household. The core reference is to the feminine—sisterly, wifely, maternal—centrality in the emotional and physical life and the economic management of the household. The supportive role of women is related to the benign goddess Laksmi, and placed in opposition to a destruction represented by the personification of death as Yama and his messengers. The Newars begin their month, and thus their new lunar year, with the bright, waxing lunar fortnight. Therefore, Swanti's first three days are at the end of the dark fortnight, ending in the dark, new moon, and the New Year's Day events of Mha Puja come at the first day of the waxing lunar fortnight of Kachalathwa.

During the weeks preceding and following Swanti there are activities in most households which set some of the context for the Swanti ceremonies. Oil lamps are placed on the ka:si , the open porch on an upper floor, which is also the principal site of the worship on the first two days of the Swanti sequence. In some households the pikha lakhu , the deified stone marking the boundary of the house, has also been worshiped during the preceding weeks as it will be in the course of the Swanti ceremonies. Family members go to the ka:si to worship swarga , "heaven." Children are expected to take important parts in this worship. In some houses during this period the individual rooms of the house are worshiped and offerings are made. Oil lamps are placed, often by children, on the pikha lakhu , in the various rooms of the house, and on the ka:si . Children, house, household, and the boundaries of the household with an encircling world are emphasized. The world encircling the household—in contrast, as we will see later, to the Devi cycle's world encircling the city—is a moral world.

These preliminary activities are echoed in the events of Swanti itself. The first two days of the sequence, which are the last two days of the lunar year, are respectively, Kwa (sometimes alternatively spelled Ko ) Puja [77] and Khica Puja [78], namely, "Crow Puja" and "Dog Puja."

Both of these creatures are understood here as "messengers" or agents of Yama, the ruler of the realm of death, as they are similarly conceived in the course of rituals following death. On the day of Crow Puja an offering is made on the ka:si . Flowers, oil-lamp wicks, incense, uncooked unhusked rice, ceremonial threads, and bits of cooked vegetarian food are placed within a mandala[*] that is drawn on the floor of the ka:si . Crows frequently come to carry off some of the food. There are no worship activities outside of the house. Kwa Puja, like all the events of Swanti, is related to the city in parallel fashion; similar units, households, are doing very much the same things everywhere throughout the city at about the same time.

On this first day of Swanti gambling begins, traditionally by casting cowrie shells and now also with card games.[3] During this period the whole city gambles. Men gamble among groups of friends[4] and fellow phuki members, and men, women, and children gamble in the household. In religious interpretation the gambling of this period is a sort of puja directed to Laksmi, the goddess of household wealth. If a gambler loses money it is an offering to Laksmi, which she will later return. If the gambler wins it is a kind of prasada , an offering to the deity that has been received and returned, a sharing in the deity's substance that affirms a dependent relationship—and a consequent protective responsibility for the now parental deity. This theme is repeated in the offering of money to Laksmi during household worship on the third day of Swanti. The festive gambling is also said to be distracting and pleasing to the messengers of Yama Raja, so that they forbear to carry off any victims, a theme that will surface again during a later day of Swanti. Gambling as a reversal of household economic order is also an "anti-structural" element of a kind that we find in several other annual events.

Khica Puja, "Dog Puja," on the second day of Swanti, is observed like the Crow Puja, except that the mandala[*] and offering are placed in front of the ground or cheli level of the house, and usually eaten by stray dogs.

On the following day, the last, the new-moon day of the waning fortnight of Kaulaga, the old lunar year ends with Laksmi Puja [79].[5] Dipavali elsewhere in South Asia is (as indicated in its name), a festival of lights. Oil lamps and wicks have been important offerings on the earlier days. On this day in Bhaktapur householders place oil lamps at each window (at least two to each side of the window) two at the main door of the house, two lamps at the door of every room, two lamps on

the ka:si , and one at the pikha lakhu . In addition, lamps are put at the door to the dukhu :, the storeroom for valuable items, which will be the site for the household puja that is performed on this day, during which offerings of light will be made to Laksmi.

The puja on Laksmi Puja, Day is a kind of apasa(n) cwanegu , a relatively simple non-Brahman-assisted household puja (app. 4). Among the offerings made to Laksmi there is a prominent offering of money. This is related to the idea of gambling as an offering. The worship of Laksmi in the dukhu : is associated with the hope of wealth and good fortune for the household in the coming year.

On the day of Laksmi Puja some members of the household will first go, as they do preceding all important household puja s, to the local neighborhood Ganesa[*] temple, to ensure effectiveness for the later worship. Upper-status families send a portion of the offerings of the household puja to their Aga(n) God, and, for those who have Taleju as an auxiliary lineage deity, to Taleju.[6] Aside from these minimal procedures, which are followed in all important household ceremonies, there is not—on this nor the other days of Swanti—any activities outside the boundaries of the household. There may be a special household dinner on this evening; it does not include the women who have married out of the household. They will return for a feast on the fifth day of the Swanti sequence.

Laksmi Puja is the first of the three main days of Swanti. On these three days the area between the pikha lakhu and the main doorway to the house is purified with cow dung. This represents a pathway for benevolent and protective deities to enter the house.

The fourth day of the five-day sequence, and the middle day of the focal final three days, is the lunar New Year's Day itself, the first day of the waxing fortnight Kachalathwa. This is Mha Puja [1], the one unit in the Swanti sequence that the Newars consider to be specific and special to themselves, not shared with other Nepalis. The term "Mha " (Kathmandu Newari, mha ), means "body," here representing the physical "seat" of each of the individuals living in the household. Essentially Mha Puja is the worshiping of each member of the household by the naki(n) , the senior active woman of the household.[7] In preparation for this ceremony, a mandala[*] is first drawn on a purified surface of the floor for each of the attending members of the household, as well as for any temporarily absent members who will be worshiped in absentia . Some households make mandalas[*] for pets living in the house, such as turtles and pet dogs. The mandalas[*] represent the human or animal body. Five

piles of unhusked rice are placed on each mandala[*] . They represent the five mahabhuta , "great (or major) elements." This refers to the Hindu conception of "the gross elements, earth, water, fire, air, ether; of which the body is supposed to be composed and into which it is dissolved" (Macdonnell 1974, 208). A covering of leaves is placed over these piles, and various offerings are placed on it, such as beaten rice, water, ceremonial threads, flowers, incense, and lamp wicks.[8] The naki(n) worships each member of the household, first males, then females, in order of descending age, in the same way in which the benign deities are worshiped. She repeats the same sequence for each household member. She begins by putting some swaga(n) (a mixture of husked rice, curds, and pigment; see app. 4) on his or her forehead, and then presents offerings of threads, flowers, garlands, sweets, and fruits. Next the naki(n) pours the contents of a rice measuring pot, in which have been placed husked rice, popped rice, flowers, and pieces of fruit, spilling it in three successive portions over the person's head. Next the naki(n) offers the meat and fish containing mixture, samhae . This is striking as a small sacrificial gesture to the body as deity, which is at this phase treated (albeit in a minimal fashion) as a dangerous deity. The mandala[*] , which had been drawn in colored rice powder, is swept up, sometimes before, sometimes after the samhae is given, depending on the family custom. After the puja there is a feast for members of the household. The Mha Puja is interpreted as helping to ensure long life and good fortune for the household members.

The final day of the Swanti sequence is Kija Puja [2], literally "younger brother puja ." Once again the sequence follows a general Nepalese and South Asian pattern. It is on this day in Swanti that the women who have been married out of the patrilineal household return to their natal homes. The puja is, as in many places, related to a tale about a sister who was able to protect her younger brother from death. She asked death's messenger if he would delay taking her brother until she had finished worshiping him, and until the flowers and fruits that she would present as offerings to her brother had wilted, faded, and spoiled. The messenger accepted her pious request. Through her prolonged puja , and through the presentation of special kinds of flowers and fruits that did not wilt, fade, or spoil, the sister was able to prevent Yama from taking her brother's life. Although the story and the name of the puja specify a sister's relation to a younger brother, and emphasizes her protective, "maternal" behavior, all the sisters in or related to a household worship both their elder and younger brothers.[9] During the

Kija Puja all men in the household are worshiped by their sisters, if necessary by classificatory "sisters" from the mother's brother's (paju ) family. A mandala[*] is made in front of each man, and on it are placed a number of foods and flowers that resist decay and fading. These are presented to the men by the women present, who worship them in the apasa(n) cwanegu fashion (app. 4). After the puja , brothers give sisters presents of saris and money. There is a movement of married women throughout the city, as they try to return to their natal home during this day. Sometimes, for example, for those women whose husbands live in the Terai, long journeys are necessary. For the majority of women, however, their natal homes are elsewhere in Bhaktapur, and the older women will try to return again from their natal homes to their husbands' homes at some time during the day to intercept and see their own visiting daughters. The day, and thus Swanti as a whole, ends with a feast at each house, with the returned married-out daughters participating.

The old lunar year comes to an end, and the new lunar year and its festival cycle begins with a set of calendrically specified events that center about Bhaktapur's smallest corporate unit, the household. In contrast to the extended patrilineal phuki unit with its dangerous lineage deity worshiped by Tantric and sacrificial rites, the household worship of Swanti, reflecting the focus of almost all household pujas on benign deities, becomes focused on the benign deity Laksmi, the ideal figure of the good housekeeper, and the deified members of the household, who are worshiped as benign deities—with the minor, but interesting exception of a minimal meat offering to the bodies of the household individuals. The unit emphasized throughout is the household and its members. The space is the house. The boundaries of the house and its component units are repeatedly marked during the course of Swanti. Exterior pujas are minimal—worship at the neighborhood Ganesa[*] shrine, necessary before all major household worship, and a gesture to the Aga(n) Deity in upper-status households.

The realm that is emphasized is the moral realm, the ordinary civic world of social relations. The rewards in this world and the ideal conditions for its activities are physical well-being, wealth, and security. The ultimate opposition that is emphasized to this world is here not the outside world of the demonic forces and dangerous deities beyond the borders who are the symbols of the outside in many other events (above

all, those of the Devi cycle), but death as personified by Yama and his messengers and agents. Yama, the king of the realm of death, is a moral agent. Souls of the dead go first to his realm, where the reckoning is made as to whether they will proceed to heaven, a rebirth, or hell. The emphasis in relation to death here is on the movement of soul, not as it is in the dangers of the Devi cycle on the destruction of the body—quite a different kind of problem and threat. There are other symbols of destruction in Bhaktapur's festivals—they have to do with impersonal forces external to the human moral realm. However, Yama as death is an important part of that realm. He can be resisted by affection and solidarity; he and his agents have human characteristics—they can be fooled, and distracted by gambling. When he does prevail in time, the dead individual must leave the household but continues in his identity in a way that has been determined by his moral and dharmic activities. The temporary overcoming of Yama is through the emotional solidarity of the household, and this solidarity is represented by sororal emotional support and by the exchange of gifts. This is in contrast to the ideas, symbols, and emotions relating to the solidarity of the phuki group, guthis , and larger corporate units where impersonal power in relation to dangerous deities is most central to their representation and protection.

Swanti also illustrates a symbolic movement. There is a flowing into the household of the protective power of the benign deity, and a return of the women the household had generated and who had left it. While the elementary unit of solidarity is the household there is the secondary solidarity of a parallelism of similar units. All households in Bhaktapur are going through the same sequences, and while most of this sequence is known to be Hindu, and more saliently Nepalese, one segment, Mha Puja, the day of the new year, is thought to be uniquely Newar, an event that, typically of Newar specialties, has Tantric and Yogic references added to the interpersonal emphases of Swanti, albeit in very attenuated form.

The Swanti sequence is of major importance in Bhaktapur as a "focal" household festival.

Miscellaneous Events [3-7]

The lunar year contains many individual events of varying importance that are thematically independent units, in contrast, for example, to the

thematic integration of Swanti. Their patterning and relations with other events in the cycle, if any, involves more abstractly structured relations, which we will consider in the appropriate places.

Jugari Na:Mi [3]

The ninth day of the bright fortnight Kachalathwa is in October/ November. This is an event in commemoration of Visnu-Narayana's[*] victory—in the form of his avatar Vamana—over an Asura king. It is a time for a pilgrimage to shrines of Visnu[*] , ideally to the four major shrines of Visnu[*] in the Kathmandu Valley, although this is now limited to a visit to one of them and often, even more conveniently, to one of the two major Visnu[*] temples within Bhaktapur. The visits may be made by a group of family members or by one person representing the family. This special day is in the context of two fortnights (Kachalaga and Kachalathwa) specially dedicated to Visnu[*] . During this period, people who wish to may worship him daily at one of the Visnu[*] temples.

People who go to the valley shrines of Visnu[*] do this along with non-Newar Nepalese, joining them in a mela . In keeping with the theme of Vamana's outwitting of the Asura, people may pray at the shrine for protection against demons, evil spirits, earthquakes, destructive rains, and the like—the nonmoral dangers that are, in the system most properly centered on and localized to Bhaktapur, the concern of the dangerous deities. From the perspective of Bhaktapur's civic religion this is an event of moderate importance.

Hari Bodhini [4]

This, like Jugari Na:mi, which it follows by two days, is a valley-wide festival dedicated to Visnu[*] , celebrated in visits to his four Kathmandu Valley shrines. This day commemorates Visnu's[*] awakening after his four-month cosmic sleep, and is celebrated throughout South Asia. It is the last day of the four-month Caturmasa Vrata (see section entitled "Ya Marhi Punhi [9]"). The Valley's activities are described in some detail by Mary Anderson (1971, chap. 20). Thousands of people from Bhaktapur usually participate in these pilgrimages, as they participate in mela s in general, for the fair-like excitement of the event. The visit is given a less frivolous justification as a fulfillment of some pledge to Visnu[*] , or in order to gain some religious merit.

Gaborieau (1982) has, as we have noted, argued that for the Indo-Nepalese, Hari Bodhini and the waking of Visnu[*] marks the end of the four-month inauspicious period in which ordinary time is mythically held in abeyance. We will return to this suggestion in chapter 16, but may note here that, in contrast with other events, it is of no internal significance to Bhaktapur, and does not mark any immediate shift in festival events. (Moderate.)[l0]

Saki Mana Punhi [5]

The day and night of all full-moon days or punhi s, that is, the last day of the bright fortnight, is the regular monthly occasion for special activities in Bhaktapur. Some individual full-moon days are differentiated in some way, as are some other monthly occasions—such as the new-moon day, the fourteenth day of the dark fortnight, and the first day of the solar month.[11] Only some of these specially named punhi s are listed in the written annual calendars; some are specially noted only because they precede an important calendrical event in the following fortnight. It is often arbitrary as to whether such relatively insignificant differentiated days should be considered as a special annual event. We have listed only those specially named full-moon days that seem associated with some activity or symbolism of more than routine differentiated importance. One of these is Saki Mana Punhi. "Saki mana" refers to the edible boiled root of a certain flower. Participation in the associated events of the day is optional. There are groups of men who go on the evening of all punhi s to various temples to play music as a religious offering. On this particular punhi evening they bring mixed grain and uncooked beans to the particular temple where they customarily play and construct an elaborate picture of the temple out of the grain and beans. This is the last day of the two fortnights dedicated to Visnu/Narayana[*] . Many people go from one shrine and temple to another, listening to music and inspecting the pictures, but the two major Narayana[*] temples are particular foci for visits and offerings. As this is a punhi evening, people also worship the moon at home, as they do on all punhi s. After the Visnu[*] and moon puja s many households eat special foods—as they do on many calendrical occasions. On this day it is saki mana , the boiled root that gives the punhi its name, and sweet potatoes. On this day, in which the household is emphasized as well as the benign deity Visnu[*] and the astral deity, the moon, there is a parallel participation of

households, not only in similar pujas , but in the eating of the same food. The movement out of the household is in a stroll to various nearby temples, which individuals, household groups, and close friends may decide to visit. There is no larger interactional civic form given to the day's events. (Moderate.)

Gopinatha Jatra [6]

This event is the first in the bright fortnight Kachalaga in November. While many calendrical events are associated with movement of people to one or another temple or pilgrimage site in a more or less haphazard manner some calendrical events are characterized by systematic and formalized movements through some unit of space. Sometimes a deity is moved through space, sometimes and more rarely devotees move to a temple or shrine, or to a series of them, in some prescribed order. Both the carrying of the deity and the more formalized movements of worshipers through the city is called, as it is elsewhere in South Asia, a jatra (from the Sanskrit, yatra , "journey, festive train, procession, pilgrimage"). These processions—most typically lead by special jatra images[12] of the focal deity carried in the arms of a priest or in a palanquin, or sometimes in an enormous chariot—move over prescribed routes. The route is often the main festival route of the city, the pradaksinapatha[*] , but for many festivals it is one of the less extensive routes within some other significant unit of the city (chap. 7). The paths by which the image and the major participants move from a temple to join the festival route are themselves conventionally prescribed. It should be noted that the extensiveness of the jatra route is no necessary indication of the importance of the festival. Minor jatras may follow the main pradaksinapatha[*] , while important ones that become foci of interest for the entire city may occasionally move only through a local area.

Gopinatha Jatra is an example of a minor jatra that follows the main city route. "Gopinatha" is an appellation of Krsna[*] . The organization of the procession is the responsibility of the temple priest, the pujari , of the Krsna[*] temple in Laeku Square. Some men of the Jyapu Rajcal (also called "Kala") thar , members of families that had been granted tenancy of land in exchange for this service, accompany the image playing flutes, drums, and cymbals. Observers are usually casual bypassers who often must ask who the deity being carried is. Bypassers often give coins as offerings to the deity, and the members of the procession give them flowers as prasada in return. (Minor.)

Bala, Ca:Re [7]

Ca:re , the fourteenth day of the dark lunar fortnight, is always special to the Dangerous Goddess. On this particular ca:re members of families who have lost someone through death during the year join other Nepalese at the great Valley shrine and temple complex of Pasupatinatha (Anderson 1971, chap. 24). The various procedures on the day—bathing, visits to temples of Siva, Bhairava, and the goddess (at her Devi pitha as Guhyesvari), all associated with various traditional and local tales—are interpreted as protecting the dead person from trouble in the afterlife of the first year, and as aiding his or her entrance into heaven.[13] Most people in Bhaktapur who have had a bereavement during the previous year try to join in this pilgrimage, which is a kind of mela . Those people who are unable to go to Pasupatinatha on that day may go to the equivalent temples and shrines of the "royal center" (see chap. 8, section entitled "Pilgrimage Gods of the Royal Center") on Bhaktapur's Laeku Square. This is one of the days within the lunar year with a central or secondary reference to "normal" death.

On Bala Ca:re a member of the Jugi thar begins to perform in Bhaktapur as Mahadeva, Siva as the "great god," performances that will continue until the beginning of the solar New Year sequence [20].

The day's major event concerns only some of Bhaktapur's people in any given year, but through their lifetimes as they become bereaved most people will take part in it. (Moderate.)

Sukhu(n) Bhisi(n)dya: Jatra [8]

This jatra begins on the fourteenth day of the waning lunar fortnight Kaulaga and ends on the last day, the fifteenth, the day of the new moon. It is special to Bhaktapur, and honors Bhimasena (in Newari, Bhisi[n] God), the special protective deity of Bhaktapur's tradesmen and shopkeepers. An image of the deity taken from the main Bhimasena temple in Dattatreya Square is carried part way around the city on the main festival route, the pradaksinapatha[*] . During the jatra procession straw mats—sukhu(n )—and piles of straw are burned along the route "to keep Bhisi(n)dya: warm." There are various legends about Bhimasena, one of the heroes of the Mahabharata epic, which are used to explain this and other details of the festival. The image is left in a protected shrine along the side of the festival route during the first night, and the procession proceeds around the remainder of the route the fol-

lowing morning. Shopkeepers and tradesmen perform sacrifices (most often of a male goat) to Bhimasena on these days and have bhwae , formal feasts, at their homes. These are nakha cakha , which include phuki members in addition to the household members, and the phuki ’s married-out women are invited. This jatra , then, is special to Bhaktapur, uses the main festival route, and involves all of Bhaktapur as a spatial unit, but concerns only one of its social components, the "sahu ," tradesmen and shopkeepers. It is the first of the year's important annual festivals taking place within the city to focus on a dangerous deity, and to entail blood sacrifice. It is the first important festival of the year to make use of—in its jatra aspect—the public civic space. (Moderate.)

Ya: Marhi Punhi [9]

Calendrical events are distributed throughout the year in clumps. The first two fortnights of the lunar year has a relatively high density of festivals. Now commencing with Thi(n)lathwa in November/December Bhaktapur has four lunar fortnights with only two very slightly differentiated full-moon days and a minor solar festival—a specially differentiated first day of a solar month. With the third fortnight of this period a month-long vrata , a period of special devotion important to all the Valley women, begins.

Ya: Marhi Punhi [9] is one of the differentiated punhi , or full-moon days. This particular one is related to the agricultural cycle, and is the first of a number of such festivals. Most of the other festivals connected with the agricultural cycle (this one being a significant exception) are tied together in the stories and actions of the "Devi cycle," which we will consider as a unit below. Ya: Marhi Punhi takes place at the end of the rice harvest (whose beginning was signaled in the major autumnal festival of Mohani [67-77]). At this time the rice harvest is usually entirely completed. During this day in most households a mixture of husked and unhusked rice is worshiped in the room used for storing grain. The purpose of the prayer is said to be that as the grain is used up the worshipers hope that the storeroom will be filled up again. The rice mixture is taken to represent Laksmi. A specially kind of sweetcake, ya: marhi , is presented as an offering to the deified rice, and after being left in the store room for four days, is eaten as prasada from Laksmi. Three of the cakes had been formed into images of Ganesa[*] , Laksmi, and Kubera, a quasi-deity who has little other reference in Bhaktapur and is

never worshiped at any other time, and who has as one of his legends the custodianship of wealth (Mani 1975, 435).[14] This is the traditional day for the giving by a tenant farmer of a share of the rice harvest to the owner of the land—although the share may now, in fact, be paid before or after this time. In the evening of this festival there is a nakhatya , and married-out women are invited to their natal homes for a feast in which various kinds of food special to the occasion are added to the ordinary feast menu. This is a household centered feast, and the household is reconstructed in the invitation to the married-out daughters. The deities are benign ones. The emphasis here—in contrast to the agricultural meanings of the Devi cycle—is not on the growth of the grain but in its location in the household as part of the household's prosperity. This is a significant illustration of the difference between the relations of the Dangerous Goddess (and her Devi cycle) to fertility and the benign one, Laksmi, to household management and well-being. Ya: Marhi Punhi is considered to be an exclusively Newar festival. (Moderate.)

Miscellaneous Events [10-11]

Ghya: Caku Sa(n)lhu [10] is a festival in the solar cycle that fell on the thirteenth day of Pohelathwa—late December in 1974/75. It always falls within a few days of this lunar date, and is noteworthy in that it is associated with the winter solstice and the beginning of the "ascending half" of the solar year, the six-month period during which the days progressively lengthen. It will be discussed in the next chapter. (Moderate.)

Chyala Punhi [11] is an ordinary punhi , with the addition that it is customary on this day to discard clay kitchen pots that are unusable on the neighborhood chwasa . Chyala is "a curry made from bamboo shoots, potatoes, peas and other vegetables" (Manandhar 1976, 136) which it was presumably customary to prepare on this punhi . It is an arbitrary decision as to whether to include such minimally differentiated monthly occasions in a list of annual events. (Minor.)

The Month of the Swasthani Vrata

As we have noted in the last chapter, the term "vrata " is often used in South Asia for any calendrically prescribed religious activity, but it has a stronger sense of "religious or ascetic observance taken upon oneself, austerity, vow, rule, holy work, such as fasting and continence" (Mac-

donnell 1974, 304). Noting that Nepalese calendrical events can be sorted into jatra s, mela s, and vrata s in this stronger sense, Bouillier (1982) has noted that among upper-caste Indo-Nepalese while participation m jatra s and mela s is "collective," vrata s may be individual, and done at home. She notes that those calendrical events special to women are vrata s "performed for the most part discretely within the family group" (1982, 91). Traditionally in South Asia vrata s, in contrast to many other forms of worship, were proper to persons of all caste levels as well as to women (Kane 1968-1977, vol. V, p. 51), but Kane notes that the Puranas[*] and digests of ritual procedures prescribe several vrata s that were specifically to be performed by women. Although there are differences in the participation of Newar and Indo-Nepalese women in festivals, Bouillier's remarks have some relevance for Bhaktapur. Thus, while men do participate in vrata s in Bhaktapur, the city's major special annual event special to women is a vrata , the Swasthani (Sanskrit, svasthani ) Vrata.

Pohelathwa and Sillathwa, the two lunar fortnights in January and February that begin on the day following Chyala Punhi, constitute one of a number of two-fortnight periods in Bhaktapur's annual calendar devoted as a whole to some special theme and activities. Within such periods some specific calendrical events may be connected to the theme, but others that occur may be independent of it. These four weeks are the period of the Swasthani Vrata. This is an important festival month for the women of the Kathmandu Valley of various ethnic groups. It has been studied at length by Linda Iltis with a focus on participation by Newar women (1985) and by Lynn Bennett as an aspect of her study of Chetri women in the Valley (1977, 1983). The vrata is based on a group of legends (Swasthani Vrata Katha : See B. M. P. Sharma [1955]),[15] which combines various traditional stories about Siva, Sati, and Parvati. The oldest known manuscript of this collection is in Newari (Iltis 1985, 8):

The Sri Swasthani Vrata Katha text is a compilation of 29-33 stones, some of which are unique versions of Puranic[*] stones popular in Hindu communities throughout South Asia, as well as others which are unique local legends which concern people and places m the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal, and explain the origins and benefits in rituals honoring the Goddess Swasthani.

Rooted in Newar language and culture, the worship of Swasthani has spread to other ethnic groups and cultures in Nepal via the trade networks of the Newars, and primarily through Newar scribes. . . . The Sri Swasthani

Vrata Katha text has been translated into Nepali, Hindi and perhaps Maithili.

The text is read aloud in successive portions, one each evening, in households in Bhaktapur in its Newari version. It is read traditionally by men, but its message, as Lynn Bennett emphasizes for the Chetris, is directed to women. Before turning to the actions of the Swasthani Vrata, something should be said of the text which is summarized in Bennett (1983, 274-306). The text deals with themes and especially conflicts of romantic love and arranged marriage; of sexuality and marriage; of sexual passion, jealousy, faithfulness, and duty; and of the transformation of a man, in this case Siva, from self-absorption to social usefulness through marriage. In the course of the stories, Parvati, the central human-like protagonist, must deal with these conflicts. She is able to get Siva, the man she loves, as husband through devotion and works (vrata ) dedicated to Swasthani (an appellation of the transcendent form of the Goddess), but it is her proper social behaviour, "her attention to the details of the ritual, her distribution of alms, and above all, her religious devotion [which are] stressed along with her asceticism" (Bennett 1983, 224). Bennett sums up the significance of Parvati in the Swasthani stories and their associated rituals (and in general) (ibid., 272f.):

The many contradictory elements which go into the Devi's role as perfect wife and mother are [now] apparent: she must be both sensual and ascetic: flirtatious and faithful; fertile and yet utterly pure. In the myths about her gentle aspects—most notably as Parvati—the goddess is all these things. She represents an ideal, a blending of opposing qualities which actual village women can never fully achieve. . . . In Hindu mythology [Parvati] . . . is the impossibly perfect model, embodying the contradictory values of Hinduism particularly as they affect women in Hindu patrilineal social structure. This, I maintain, is why the gentle side of the goddess is especially important to village women.

Like Durga, of course, Parvati is worshiped and greatly revered by both men and women. But, lust as men are largely responsible for the worship of Durga and more conversant than women with the texts about her, women are more involved with the rituals and texts concerning Parvati and the other gentle forms of the goddess.

Although Swasthani is the Goddess as full creative deity, in accordance with the emphasis on Parvati as the ideal woman centrally located in the social and moral world the festival is devoted to the ordinary deities, and in the stories and in the symbolic enactments, it is Parvati's

conventional relations to the benign male deities Siva and Visnu[*] that are emphasized. The events of this month are not part of the Devi cycle. We may note here that among other valley Hindu groups there is another very important women's festival connected with the Swasthani stories, Tij, which is not observed by the women of Bhaktapur (see section on miscellaneous minor events [52-58], below).

During this month the general Valley pattern is followed. Successive sections of the Swasthani Vrata Katha are read in the household each evening during the month. Girls and women past the Ihi ceremony, and, for those who had had a "social marriage" whose husbands are still living,[16] will take part in the other ceremonies, the vrata s themselves. These "married" girls and women (in some, but not all thar s) may wear red sari s, the color of marriage sari s, during this period. Some of them fast by not eating meat. They worship Siva, usually as a linga[*] ,[17] both at home and at various designated tirthas at the riverside. While a majority, perhaps, of women remain in Bhaktapur and do not participate in the major valley pilgrimages of the period, many women do participate in the valley-wide mela (described in detail in Iltis [1985]). The motives for womens' religious activities during the period are said to be ones similar to those Bennett (1983, 276) has noted for valley Chetri women—for example, for married women, to protect their households and their husbands; for unmarried girls, to help ensure a good husband in the future.[18]

Men in Bhaktapur also participate in the festival, but what was reported as having previously been daily participation had diminished greatly by the time of this study. The foci of the men's worship were Visnu[*] and Siva, important actors in the Swasthani story. On each day of the month men would go in groups, following a leader, to bathe in the river and then on to the city's main Visnu[*] and Siva temples to do puja . The leader of the group would call out the names of Visnu[*] and his avatar s and the various names of Siva, and the men in the group, carrying banners, would chant "Hari Madya:" ("Hari" is one of the appellations of Visnu/Narayana[*] and "Madya:," that is, Mahadya:, the Great God, a major appellation of Siva.) The activities of the Swastani month end on the full-moon day, with the Madya: Jatra [14], which we will discuss below.

Sarasvati Festivals [12, 13]

Sarasvati Jatra [12] takes place on the night of the fourth day of the fortnight, and is part of a unit or sequence that includes the events of

the following day ([13], below). On the day of Sarasvati Jatra students, for whom Sarasvati is a patron deity, go to her main temple, and massage the legs of her jatra image. It is said that she has just returned from a long journey from Lhasa in Tibet, and her legs are tired.[19] In the course of the day the image, on this day referred to as "Sarasvati who has returned from Lhasa" is carried around the main festival route, in a small procession, or jatra . (Minor.)

Sri Pa(n)chami [13], which occurs the next day, continues the special worship of Sarasvati or (an alternate appellation) Sri, in common with other Nepalese Hindus. This is again primarily a festival for students and their households. The students fast by not eating meat on this day. They go to the main Sarasvati temple to pray for success in their studies. Prasada from the deity is brought back to the household to be shared. Men and women Jyapus also go on this day to the temple and pray to Sarasvati for aid in the weaving of cloth and in farmwork. People from other groups may worship her at her temple on that day, particularly those who, like the students, have or wish to have skills that require study and memory.

Jyapu bhajana groups play music at the Sarasvati temple on this day. They play special music called "Basanta" or "spring music"—although Basanta, starting in Caitra (Caulathwa), is still two months away, for this day is the traditional lunar event associated with the early part of the "ascending half" of the year, which had begun some three weeks earlier.

Sri Pa(n)chami is important to essential members of the city's society and is thus in our scale of "moderate" importance for the city.

Madya: Jatra [14] End of Swasthani Vrata

This jatra comes on the final day, the full-moon day, of Sillathwa. This day is also the last day of the four weeks of the Swasthani Vrata. This full-moon day is called "Swasthani Punhi" or "Si Punhi." The day is said to be an important event—but many of the activities previously associated with it have been discontinued. A procession honoring Siva begins at the riverside at the Khware ghat[*] and proceeds to the nearby Ga:hiti Square, where it joins the main festival route, and then proceeds around it. The procession stops temporarily at the two main Narayana[*] temples, one in the upper half of the city and the other in the lower half, then continuing its circumambulation of the festival route returns to

Ga:hiti Square, and then to the river, where it disbands.[20] This jatra takes place during the day. Previously in the evening children and adults dressed as Siva and Parvati were carried around the city in palanquins, accompanied by torches and music. Still now on this day people often perform special puja s to Siva as "Madya:" (Mahadya:, the "Great God") in their homes and to his representations as linga[*] s at the riverside. These activities are an extension of the worship of Siva lingas[*] during the course of the Svasthani month. In the evening there are household suppers in which various sweets, including special forms of sweetcakes dedicated to Mahadya:, are eaten. Traditionally 108 of these tiny cakes were presented to wives, who would then eat one hundred of them, and present the remaining eight to her husband.[21]

The themes of the previous month are summed up with this act of wifely household devotion in the context of worship of the benign deities. What is added here is a jatra that emphasizes the integration of the city through its visits to the two Visnu[*] temples, and the circumambulation of the main festival route.

The procession is a relatively small one now. Most people do not join it but go about their ordinary activities during the day. (Moderate.)

Sila Ca:re (Sivaratri) [15]

The following waning fortnight, Sillaga (in February) has only one festival event, of moderate importance for Bhaktapur as a city—although of major importance for all Shaivite Hindus.

This ca:re , the fourteenth day of the dark fortnight, is—like all ca:re —special to the Goddess, and there are as on other ca:re s special ceremonies for the Aga(n) Gods and at the temples of the Tantric deities. This particular ca:re is also devoted to Siva.[22] On this day the major valley shrine complex of Pasupatinatha becomes a center for Shaivite pilgrims from India and Nepal. Bhaktapur's Dattatreya temple is a secondary pilgrimage center at this time. Many Shaivite pilgrims from India and elsewhere in Nepal—both "householders" and sadhu s—come to Bhaktapur at this time. Some of the sadhu s are housed at one or another of the city's matha[*] s, "monasteries," for wandering Hindu renouncers, built as acts of piety by Malla kings. As we have noted, neither Dattatreya temple nor the matha s have "Newar" priests. These pilgrims (and others during the course of the year) come to Bhaktapur in a sort of benign invasion of interest to its citizens, but they are not, as such, part of the Newars' own city-centered symbolic life.

People in Bhaktapur may go themselves to the Dattatreya temple,

and, as pilgrims themselves, to the fair-like mela at Pasupatinatha. Within Bhaktapur in the evening fires are made along the roadside and in the main neighborhood squares. Many men—from thar s throughout Bhaktapur's social structure (except the untouchables)—sit by the fires all night chanting the name of Siva, some of them smoking cannabis, which is commonly smoked by Shaivite pilgrims during the festival, and which was, at the time of this study, sold by stall keepers at Pasupatinatha during the mela . The legends told to explain the fires are variants of a widespread Hindu tale associated with the day (cf. Kane 1968-1977, vol. V, p. 255). In summary, the legends recount that once upon a time a hunter caught in the woods at night sat shivering under the particular kind of tree whose wood is supposed to be burnt for the fires made that night. Siva, hearing the sounds "sh, sh" made by the shivering man, thought that the man was calling his name, and manifested himself to offer the hunter a boon. The hunter requested that he be able to stay forever with Siva in his heaven, and Siva granted his wish. The salvation of the shivering hunter under his tree, is said by some to be associated with the approach of spring when trees are beginning to bud again and that Siva who periodically destroys and recreates the world is bringing it to life again in its annual cycle of death and rebirth. There are no feasts or special household activities on this day.

This is one of the calendrical events in which the borders of the domestic moral realm is represented by means of the ideas and images associated with the benign deities. Siva responds, in his absentminded but recognizably human way, to the needs of the hunter. That response is produced by a misunderstanding, a kind of trickery, for the hunter[23] has done nothing in the dharmic moral realm to earn it. The legend, the fires in the public spaces in whose warmth some men spend the night, the smoking of cannabis, the references to and mimicking of the absent-minded and yogic Siva probes at the human outer boundaries of the moral realm.

In the day's explorations of the "benign margins" of the moral realm, neither the household nor the integrated city are directly referred to but are present as that which is being, for the moment, escaped. (Moderate.)

The Minor Festivals of Krsna[*] (Holi) [16, 17]

Cillathwa, the bright fortnight of the following month (February/ March) includes a period—from the eighth day until the full-moon

day—which in the other Newar cities of the Valley as in South Asia in general is a time for major activities devoted to Krsna[*] . In Bhaktapur the activities of the period are comparatively quite minor. The first day, the eighth, is called "Cir Swaegu" [16], which means "to erect a cir ," that is, a bamboo pole to which a banner of varicolored cloths has been attached. The practice, which gives its name to the day is, significantly, not done in Bhaktapur now (although it was, on the evidence of the name, probably done sometime in the past), although it is still done in Kathmandu (Anderson 1971, 250). In Bhaktapur the day simply introduces the week, but has no special activities of its own. In both Kathmandu and, even more so, in Patan Krsna[*] is associated with major festivals. In Bhaktapur some of these are ignored, others given only minor importance. This is an example of the selection of deities and emphases that are open to each community.

In the period between the Cir Swaegu day and the full-moon day, called "Holi Punhi," some people go in processions around the city, and throw abhir , a red powder (app. 4). The men in these processions, few in number compared to the numbers participating in the city's major jatra s, are mostly from the Jyapu thar s. Their throwing of the powder is restrained in that they are, it is said, "afraid" to throw the abhir at men of superior thar status. This is in contrast to Anderson's account for elsewhere in the Valley that "the erection of the cir pole gives eight-day license to one and all to drench almost anyone he meets, including cows and dogs, with powder of the most brilliant vermilion" (1971, 251). She reports that the traditional license of the period was being brought under control in Kathmandu because it was becoming a public nuisance.

As we have argued previously in our discussion of Krsna[*] and Rama as objects of bhakti , personal devotion, bhakti religion is antithetical to the traditional community organization that Bhaktapur's Hinduism helps constitute and support. Gopal Singh Nepali found some evidence in the phrasing of a folk song about it, that Holi (as the week-long period is called elsewhere) is a "culture trait introduced from outside [Nepal]" (1965, 338). Its popularity in Kathmandu and Patan, along with that of other Krsna[*] festivals, may attest to a relative breaking away from traditional priestly Hindu civic organization at the time of its introduction in contrast to the more conservative and traditional Bhaktapur.

On the last day of the period, Holi Punhi, [17], or, as it is also called, Krsna[*] Jatra, in Bhaktapur an image of Krsna[*] that is kept in the Taleju

temple[24] is carried around the city's main festival route. Not many people go out of their way to watch the procession. There are no other special activities on that day. (Both [16] and [17] are comparatively minor events in Bhaktapur.)

The Approach of the Season of Anxiety [18, 19]

The waning fortnight Sillaga (March) has no special events, with the exception of Pasa Ca:re [18], the fourteenth day, one of the ca:re s with special features. "Pasa " means "friend." In Bhaktapur the day is also called Pisac Ca:re, a pisaca being a ghoul-like evil spirit. In Kathmandu, where the day was traditionally the occasion for more elaborate celebrations than in Bhaktapur, the day is called "Paha(n) Ca:re," that is, "Guest Ca:re." In Bhaktapur there are special emphases on the day in the Tantric worship of tutelary goddesses required on all ca:re . Thus, in the Taleju temple it is necessary to offer an animal sacrifice to Taleju, while on most other ca:re the meat-containing mixture, samhae , is sufficient. In Aga(n) puja s people add references to the pisaca and ask for protection. Many farmers' guthis perform blood sacrifices to dangerous deities. Those people who have protective pollution-consuming deified stones, "Luku Mahadya:," in their courtyards (chap. 8), clean them on this day. The main idea on this day, is protection from vague evil forces. Anderson remarks that this ca:re comes at a time "when typhoid, dysentery, cholera and smallpox flourish with the advent of hot weather, prior to cleansing monsoon rains. It is a time of uneasiness" (1971, 264). The anxieties symbolized by spirits and the special worship of the dangerous tutelary gods, are thematically balanced by feasts in households, to which married-out women and friends are invited—hence the names "Pasa" and "Paha(n)." As Anderson puts it, "traditionally on this day homes and courtyards are thoroughly cleaned and decorated to welcome relatives and acquaintances in the hope that such a display of goodwill, generosity and mutual love will dispel evil thoughts and harmful spirits. Especially it is important to invite married daughters back to paternal homes for family feasts, that sisters may meet in good fellowship" (1971, 265).[25] (Moderate.)

Two days later, on the first day of the following fortnight, the bright fortnight Caulathwa (March/April), is the day of Cika(n) Buyegu [19], the "oil-rubbing" day. For the upper thar s, the Chathariya and above, there are no special activities on this day, but the farming thar s and

some thar s below them in Bhaktapur and in other Newar communities rub mustard-seed oil, cika(n) , on their own and their children's bodies. It is thought that this will protect them from sickness during the following year.[26] This is followed by a special household supper. (Minor.)

The themes of dangerous spirits and illness and of protection against them, which are introduced here, are the first anticipatory references in the lunar cycle to a time of the year in which a long season of disease and the critical early stages of the main agricultural cycle, the rice cycle, bringing major risks for individual and civic well-being, are approaching. These anxious themes become represented in later calendrical events (mostly within the Devi cycle) with increasing density and interrelation.

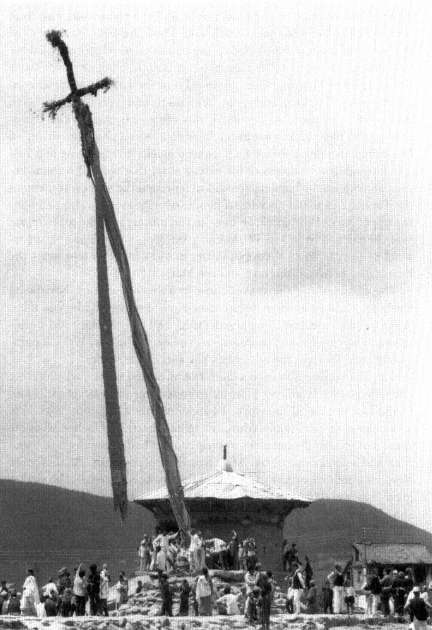

Biska:, The Solar New Year [20-29]

In 1975/76 the solar New Year sequence began on the eleventh day of the waxing lunar fortnight Caulathwa, during April. This sequence lasts for nine days, and includes several component events. We will present these in the following chapter in conjunction with the other events of the solar calendar. The sequence as a whole is of focal importance for Bhaktapur, in ways that we will specify. It centers around the dangerous deities, and is concerned with the integration of city units in the face of the passions that can destroy that unity.

The Dewali Period, the Worship of the Digu Lineage Deities [30]

The period starting on the first day of the dark fortnight, Caulaga (April) and ending some fifty days later on the day before Sithi Nakha [36], is the span during which the worship of each phuki ’s externally situated lineage deity, the Digu Dya:, must take place. Each phuki has a particular day within the Dewali period when it customarily does its Dewali puja . We have discussed the events of this period in chapter 9. The Dewali worship is to a dangerous deity through meat and alcoholic offerings. It is the most important ritual marker of the phuki (Major.)

The Minor Dasai(n) of Rama [31, 32]

In our consideration of the Krsna[*] ceremonies of Holi we had examples of ceremonial days in Bhaktapur's calendar which are of interest be-