Robert K. Bonine and the Production of Actualities: 1906-1907

Although fiction films were the Kinetograph Department's principal product, the Edison Manufacturing Company still continued to produce a significant number of actualities during 1906 and the first half of 1907. Here a simple division of labor was generally observed. Porter's filmmaking energies were directed almost exclusively to the production of acted "features," while Robert K. Bonine traveled around the country and to the new U.S. territorial possessions, where he took actuality subjects. His films were sold primarily to traveling motion picture exhibitors then taking refuge in the travelogue, old-time stereopticon lecturers finally incorporating films into their programs, and exchanges servicing vaudeville theaters retaining a residual interest in travel scenes and news topicals. Hale's Tours and similar shows also provided a significant market during 1906.

Shortly after the earthquake in San Francisco on April 18, 1906, Bonine went to the West Coast and filmed the remains of the destroyed city, including Panorama Russian and Nob Hill from an Automobile and Dynamiting Ruins and Rescuing Soldiers Caught in the Fallen Walls . Thirteen short subjects were put on sale, and film exchanges and exhibitors were informed that "any selection of subjects may be joined together. Every film is provided with an Edison announcement plainly describing each scene and greatly adding to the interest and value of each picture."[83] The earthquake's news value was such that Edison sold between twenty-two and sixty-eight copies of these films, in many cases to exchanges that rarely purchased news films.

After photographing the San Francisco devastation, the Edison cameraman traveled south and filmed Flora Fiesta, Los Angeles on May 22, 1906. The San Francisco disaster had created concern about dangerous earthquakes in Southern California and the week-long festival was designed to refurbish the city's image. A quarter of a million people reportedly attended the flower fete

"in perfect May weather, beneath an amorous sun, tempered by deliciously cool winds from the sunset sea." According to the Los Angeles Times , the 250,000 saw the most memorable sight of their lives, and "the day was, from every point, the greatest in the city's history."[84] Bonine was probably hired by local businessmen who wanted the parade filmed for promotional purposes. If so, their efforts were not notably successful, since Edison sold only three copies in the next nine months.

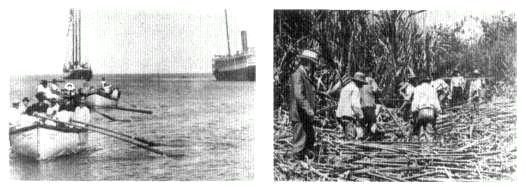

After completing his obligations in Los Angeles, Bonine returned to San Francisco, where he received an invitation for a Hawaiian film trip. On May 28th, he cabled the Hawaiian Promotion Committee that he would come.[85] Three days later he left for the islands, where he had earlier taken films for the Biograph Company. His original intention was to travel on to Japan, but Hawaii lured him into a protracted stay: he did not head back to the mainland until August 14th.[86] Cooperating with, and probably subsidized by, the islands' local railroad company and their promotional committee, he photographed a series of short films under the rubric Scenes and Incidents Hawaiian Islands . Subjects included Hawaiians Arriving to Attend a "Luau" or Native Feast ; Shearing Sheep, Humunla Ranch, Hawaii ; and Panoramic View of Waikiki Beach, Honolulu .[87] On his way back home, Bonine filmed in Yellowstone National Park during the late summer.[88] Sales for Bonine's Hawaiian subjects averaged ten to twelve copies over the next six months. A Trip Through the Yellowstone was offered as a 735-foot feature and sold twenty-one copies; some of these must have circulated among nickelodeons that were short on product and/or looking for respectable "educational" subjects that might appeal to middle-class patrons and local authorities. While individual scenes of Yellowstone were sold in 75- to 140-foot lengths, only one or two copies were generally purchased.

With Bonine away on his trip, Porter almost certainly was needed to take Scenes and Incidents, U.S. Military Academy, West Point and films of local sporting events such as The Vanderbilt Cup and Harvard-Yale Boat Race . These sold between three and eight copies. On July 31, 1906, he also filmed Auto Climbing Contest , which took place at Crawford Notch, New Hampshire. It was sponsored by the Bay State Automobile Association and photographed for Percival Waters at the request of the Keith organization. Alex T. Moore subsequently indicated that these subjects were acknowledged money losers and only made to please important customers.[89] Such films found their way into theaters on special occasions, but were ill suited to the rental system that had sprung up, since topicality limited the period over which an exchange could realistically expect to recoup its investment.

In March 1907, four months after President Roosevelt's trip to the Panama Canal, Bonine accompanied Alfred Patek, former managing editor of the Denver Times , and Frank Webster, another Denver newspaperman, to Panama, where he took films and slides of the Canal Zone under their supervision. Scenes

Robert K. Bonine's films of Hawaii.

showing life on the isthmus and the canal's construction included Panorama of Old French Machinery ; U.S. Sanitary Squad Fumigating a House ; and "Making the Dirt Fly. "[90] Once again Bonine took a number of slides and films about a specific subject around which exhibitors could construct programs.

Bonine's travel films were used by exhibitors to celebrate nature both as natural beauty and natural resource. With one group of films, those on Hawaii, the photographer himself became an exhibitor, presenting his own program at several venues, including the Orange Camera Club in May 1907.[91] His Hawaiian travelogue showed the picturesque quality of this overseas territory, acquired at the beginning of the Spanish-American War. Such programs made America's distant possessions seem more concrete and desirable by featuring Hawaii's exotic, unspoiled scenery and its modest contribution to the U.S. economy.

A similar program on the Panama Canal was given by Alfred Patek, who had supervised Bonine's photography in the Canal Zone. Using fifteen Bonine films and two hundred slides (many, but not all, taken by Bonine on the same trip), he presented his program in Denver on April 23, 1907. According to one review, Patek's lecture combined "an intelligent and comprehensive review of the great canal work, past, present and future with pictures that explain better than words all the phases of governmental work in Panama and the life of the natives and the Americans who are carrying on the tremendous undertaking of our Government."[92] Such a program retrospectively justified President Roosevelt's sponsorship of Panama's 1903 secession from Columbia, which had enabled the United States to build the canal. (A treaty in 1904 guaranteed Panama's independence, while the United States acquired sovereignty over the Canal Zone in perpetuity.)[93] The Bonine/Patek films pointed toward the canal's completion, when it would be an economic and military asset. At a time when isolationist feelings were still strong, these pictures, like those of Hawaii, buttressed the principles of American imperialism.[94]

As with his Hawaii films, Bonine's scenes of Yellowstone showed Americans the natural beauty of their country and underlined the necessity of protecting it from short-sighted exploitation. One set of films was used by E. C. Culver, a veteran stage driver who had spent twenty years in Yellowstone National Park. Culver spent the off-season giving illustrated lectures sponsored by the U.S. Department of the Interior and the Yellowstone Park Transportation Company (his previous presentations had used only stereopticon slides).[95] Like most travelogues, they were designed to spur tourism and to turn nature, exempt from exploitation as natural resource, into a commodity of a different form.[96] Unlike Porter's and James Smith's earlier films of New York slums and quotidian events or Abadie's films of Europe and the Middle East, Bonine's actualities affirmed the expansionist ambitions of Roosevelt and big business. They supported the president's actions, which Porter often burlesqued.

With Edison giving nonfiction films a low priority, Bonine decided to leave the company's employ. Before he left in mid May 1907, he may have taken one other "series of about 20 motion pictures." These were shot at the Walkover Shoe Plant in Brockton, Massachusetts, for the George Keith Company.[97] The Walkover Shoe Company later distributed these films as a way to promote its products.[98] Pushed to the periphery of the motion picture business by the popularity of fiction films, Bonine became embittered. In June, shortly after he left, the cinematographer expressed his unhappiness to a Hawaiian friend:

You can't imagine the great demand there has been for moving picture films within the past year, due of course to the great number of cheap picture shows springing up all over the country, but the demand is all for "comedy" or, in other words, anything of a subjective nature, and it was the demand for this class of work that kept the place so busy and held my Hawaiian subjects back so long.

This part of the business is handled in a separate department in New York where they can secure the "talent" or actors, costumes, scenic painters, etc., but the developing and finishing is all done here at the factory. My intention was to quit with the Edison company on my return last fall, but I did not want to leave the Hawaiian subjects until they were finished and the work completed, so I remained on until several weeks ago on finishing up my Panama canal subjects.

I have resigned my position now and am making preparations to make a western trip some time quite soon and on over to the islands sometime in July, so am looking forward to seeing you again and giving you an opportunity to see the pictures I made last summer.

I have purchased a set of my Hawaiian scenes and a complete projecting apparatus with the object of giving some exhibitions and [plan to] make a number of other scenes which I was unable to get last summer as I will be much better equipped this time and able to make and finish the work, complete and exhibit it before leaving the islands.

My Hawaiian plate negatives were all put away in storage, as I was unable to do anything with them and just at present I am pushing my Panama negatives for lantern slide purposes, there being a temporary demand for them owing to a number of Senators and M.C.'s having been down there this past winter.[99]

Bonine's Hawaiian trip was part of a world tour, during which he took films for the U.S. government.[100] He eventually settled in Hawaii, where he continued his film and photographic activities until he died in Honolulu on September 11, 1923.[101] His departure from Edison virtually ended the company's activities in nonfiction filmmaking.