North to the Frontera:

A Period of Transition

Los Smith, Marquez, Castellanos, and other families left Calmallí when production in the mines declined. Although many migrants eventually

arrived at towns on the U.S. side of the border, the march from Calmallí was a long one. Some families went to the border following El Camino Real, hitting the various mining spots along the way. Others, like the Castellanos and Marquez, went first by land, then boarded company steamers that took them directly into the United States. But even these journeys were long episodes interwoven with specific landscapes, mining towns, and social interrelations.

This period was not simply a continuation of the mining circuit; rather, it was a period of transition. The towns of the mining circuit were slowly fading from importance as fewer and fewer booms followed busts. Migrants now turned to the frontera region, whose economic sustenance derived from the development of the border towns of Calexico and San Diego. As migrants crossed the border they left not only the Mexican peninsula but also the life-style of the desert. This transition is clearly visible in the last trek of the Smith, Marquez, and Castellanos families. Los Marquez and Castellanos returned more than once to the Baja mines after crossing the border, but ultimately the mines failed and the border economy accelerated, luring families across the line to settle.

Los Castellanos:

To San Diego and Back

In addition to the collapse of the mining economy, the Castellanos gave other reasons for their northward migration. Francisca states that an American foreman persuaded them to head north. Furthermore, Narcisso, who had hired a tutor for his older children, was worried about the education of his offspring. This concern too figured in the final move to San Diego.

Narcisso and Cleofas first traveled to the small town of San Regis (about forty miles north of Calmallí) where a third son, Narcisso, was born in 1904. After his birth the family crossed the desert to the Pacific landing of Santa Catarina (about fifty miles south of El Rosario), a port that fed a variety of company towns in the adjacent interior. Francisca Castellanos (my godmother) told me of the trip, which I recorded in field notes: "Nina [my godmother, Francisca Castellanos] remembers traveling by land through the desert with the family. Most of this travel was done on burro or horseback. [She remembers that] it was hot. A guide who was with them would keep his head covered with a sheet for protection against the sun. He was carrying Chicho [Narcisso], an

infant at the time" (12/17/75). "Un viejito" (a little old man), Cevero, accompanied the family from Calmallí to Santa Catarina. There at the port, along with others, they boarded a steamer, the St. Denis, which was going to San Diego. From shore small rowboats lightered passengers and cargo to the waiting steamer. The St. Denis made regular trips between the northern peninsula and San Diego, stopping at San Quintín and Ensenada before going across the international border into San Diego bay. The Castellanos arrived in 1905 and "immigrated" at the Port of San Diego.

The Castellanos' initial move across the border, however, was not permanent. In the next four years they returned twice to the Baja California mines before finally settling in the border zone. In 1906 and again in 1908 Narcisso Castellanos and the family returned to the peninsula. Both of these return trips were for the birth of children. Narcisso had insisted that all the children be born in Mexico. In 1906 Cleofas was with child and the family returned to Santa Catarina, as they had left, by steamer. From the Santa Catarina landing Cleofas, the children, and Narcisso made their way to the small mine of Julio César, some ten miles inland from the coast. There in January of 1906 a son, Tiburcio, was born. When Cleofas was well enough to travel, the family embarked again for San Diego. "As soon as my mother completed her diet we returned to San Diego" (Tiburcio Castellanos, 7/21/76). Within two years the family boarded for Santa Catarina again, this time for the birth of Ricardo. Landing once more at Catarina, the family made its way to the onyx mines of El Marmol, about fifty miles inland from the coast. That same year, 1908, the family packed up and returned to San Diego. This trip was the final one and the move to San Diego became permanent. "It was the same thing, my mother completed her diet and we returned to San Diego" (Tiburcio Castellanos, 7/21/76).

The Castellanos' return visits to the district proved beneficial because they renewed contacts with many old family friends. Los Sotelos, los Simpson, and others were still in the mining circuit. And Ramona Castellanos had the opportunity to see Ursino Alvarez, who was apparently working at the inland mine. Don Loreto tells of the romance and of the mining environment of El Marmol.

He was courting since they were down there in El Marmol. They [Los Castellanos] were also down there in El Marmol which is in a mountain area down below San Quintín.

I don't know how many years the mine lasted. They stopped

mining just like that . . . and then began again. It was a company from San Diego. A very large steamer went to the port there. The port was called Santa Catarina. It was a small pueblo with a spring. The wagons passed through there. They pulled the wagons with mules, from El Marmol to the edge of the beach. Just imagine. It took them two days. That's right.

In San Diego Narcisso and Cleofas joined other families that had traveled the mining circuit, and in turn they all received incoming peninsular families. Within the next decade the Castellanos traveled to Calexico where they reestablished numerous acquaintances.

Los Smith:

The Trek To Calexico

As Calmallí production dwindled and work there diminished, families dispersed and moved to other towns. Most went to mining sites within the central desert. Los Marquez traveled northwest along El Camino Real to Punta Prieta. Guillermo Simpson and family went farther north to San Fernando, and los Castellanos to San Regis. It is probable that many families went south and home. Los Smith, however, went north to the valley of San Quintín.

During the years 1906–1908, after leaving Comondú, Manuel and Apolonia Smith traveled at least four hundred miles. They moved to Calmallí, then followed El Camino Real through Punta Prieta, Laguna Chapala, San Fernando, El Rosario, and into the then small agricultural zone of San Quintín. In San Quintín they arrived at the home of Juana and Salvador Mesa. (Los Mesa had previously stopped in Calmallí, and although they had remained only a few months, this stay reinforced the two families' ties.) Hirginia Mesa, who now resides in Maneadero (about seven miles south of Ensenada), remembers the visit of Manuel and Apolonia. They had come very far and were looking for work. Manuel worked there during the harvest in the agricultural fields. Later Hirginia and her sister Paula ventured into the north and renewed ties with Manuel, Apolonia, and their children.

From San Quintín Manuel went further north to El Alamo, where a new strike had attracted people to the mines. But like other mines, El Alamo lasted only a short time. As contemporary reports illustrate:

On the western side of the plain, some forty-five miles south of Real Del Castillo, is the Santa Clara placer district and what remains of the old mining camp of El Alamo. Here, early in 1889, several thousand gold seekers converged, and Goldbaum, representing the government, helped to collect mining fees and give possession to claimants. (Lingenfelter 45 in Goldbaum 1971:52)

The rush only lasted a few months, however, although quartz mining continued in the vicinity off and on for many years. (Southworth 74, 89 in Goldbaum 1971:52)

In 1905 Nelson described El Alamo: " . . . with its vacant houses and dilapidated appearance [it was] a typical broken mining camp. There were many signs of former activity here in considerable scale, but at this time only a few men were working. New supplies were being sent in and a revival of work was being announced with the usual sanguine expectations."

In El Alamo Manuel worked the mines while Adalberto, now older, took to the campo (countryside) as a leñador . Rosa Salgado,[10] a native Palpal, Indian, who was to become part of the Smith network, recalls their arrival and also reveals the close ties that developed in the mining community.

R. Alvarez: Aunt Rosa, did you ever meet the parents of my grandfather Adalberto?

Rosa Salgado: Yes, I met them when they had just arrived from the south. At that time I was working for a lady.

R. Alvarez: Where, Aunt Rosa?

Rosa Salgado: There in El Alamo. They arrived there. They had come from the south.

R. Alvarez: Did they stay there very long?

Rosa Salgado: Yes, they stayed there a while because their father Manuel was working there. Ooh! There was a lot of people working there in the mines. He started working there as soon as he arrived. Working there in the mines. He had Adalberto with him . . . Adalberto was very young.

I have a brother and Adalberto came to the house and would invite him way up to the hills to collect firewood. They took

burros. My brother would go with him and bring firewood. Adalberto collected [firewood] and loaded the burro, and he would leave firewood for us too. Adalberto and two sisters came with the family. One, Maria, she's the one that's still alive, right? The other sister was Panchita. The two girls looked exactly the same. Then there was another boy. I don't remember what his name was. (6/18/76)

Apolonia had her fourth child, Manuel, here but lost a child, Panchita, who had come ill from Calmallí. While Panchita was ill, Apolonia sent her to los Larrinagas in Ensenada. They were kin from Comondú and they cared for her while they sought medical help. But she came back to El Alamo, where she passed away. "The girl didn't last the year. She got sick, I believe. I went with them when they buried her there in El Alamo. Such a beautiful girl. She had long braids, all the way to her waist" (6/18/76). The loss of Francisca played a strong role in the family's next move north. María states that this was the crucial reason for the move to Calexico. Her mother was grieving and wanted to be in another location.

Around 1914 Manuel and Apolonia went north with a stream of other families to the developing region of Calexico. Following the pattern established when they first left Comondú, they left El Alamo with a group of other families from the home region, As described by Maria, the surviving daughter, "Era una carpatada de familias" (It was a carpet of families). That included los Blackwell and other friends.

When the families arrived in Mexicali, they went directly across the border to Calexico. In 1910–1915 Mexicali was only a region of ranches and farms, but Calexico, across the line, was the center of activity for the Mexicali valley. There los Smith were reunited and received families from the south. Among these families were a host of kin who sought out los Smith in Calexico and reestablished close ties in a social cluster that merged with other mining families later.

Don Loreto Marquez:

El Cajon and the Mines Again

Don Loreto lived as a miner throughout his traveling through the peninsula. In the boom days of Calmallí, as in Las Flores and Santa Rosalía, he had always succeeded in working good jobs. He learned

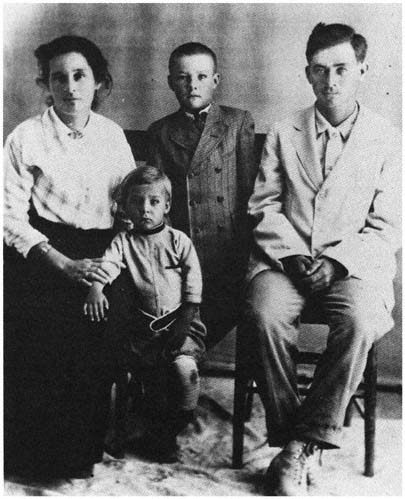

Los Smith in Calexico, c. 1915. Left to right, Apolonia Mesa-Smith, Jesus,

Manuel, and Adalberto.

(Courtesy of Flora Fernandez de Smith)

skills that he used in mining as well as later in life. He learned blacksmithing and he worked in the foundries of various towns. Around 1905, when he left Calmallí, it was not solely a departure from a job and friends. The move marked a transition into the north that would

take him and his family into the United States and that would present a new and different way of life.

The move north for Loreto Marquez was slow, as for many other individuals. He first stopped and worked in the Punta Prieta mine, which died a quick death. Forced to work elsewhere, he went to San Quintín around 1909. Then, like the Castellanos, he headed to San Diego. This initial move to San Diego was not permanent and the old life in the mines beckoned him. He returned to the mining circuit with an old "boss" and remained for six years before returning to his parents in San Diego county. The hardships of the mining life are clear in the Marquez case.

I came here to San Diego first in 1910. My sister . . . was already here. She had come from the mine down there in Punta Prieta. But we stayed there in Punta Prieta, me and my brother, my mother and father. But there was no work. We were there in the desert, that's it.

When the work ended we stayed in Punta Prieta. We were there, moving over here and over there looking for any little pebble to survive. The boss gave us whatever he could get He came from Ensenada and brought whatever little thing in the boat. And he maintained us there. I don't know what they did with the mill after the company abandoned Punta Prieta.

When they put the mill up, it was an eight-stamp mill, that's all. It was very small. The company wasn't able to work any longer because they spent so much to put up the mill. It was very costly and a lot of work.

The company brought an engineer, a German, who had been the engineer in the Port of Ensenada. He got along with everyone there. My boss, Brown, took him to Punta Prieta. And that German put up the mill. Flick was his name. Flick . . . big as hell. He was a very good person, that's for sure. Remember that when the work ended they all went to the United States. The German came up here to Los Angeles; he had a job to do around there. But we stayed there in Punta Prieta without work.

When the boat from Ensenada arrived . . . they brought us a letter for my father. The German . . . got a contract in San Quintín and he wanted my father to send us there to work with him. San Quintín is located below Ensenada. (2/18/76:13–14)

The valley of San Quintín lies approximately 190 miles north of Punta Prieta on the Pacific Coast. Along with Ensenada, the town had been a major northern port of trade during the nineteenth-century otter trade; it later became a major agricultural experiment First owned by Americans, then later by a British company, San Quintín was converted into a wheat-growing district. A large flour mill was built and dry farming of wheat was practiced for many years. Mexican, English, and American colonists began settling the region, but successive droughts brought doom to the colony. Well-conceived plans for a northern connecting railroad, for which some track had already been laid, died along with the crops.

The mill, railroad tracks, and other machinery were all that remained of the venture, and a crew was hired to dismember the mill and salvage all that was possible. Don Loreto and his brother, Doroteo, went to San Quintín as part of the salvage crew.

Well, there had been a flour mill in San Quintín, but I don't know when. A very rich company from England, owned by an Englishman, planted who knows how many sacks of wheat there. There are beautiful lands in San Quintín close to the water marsh. They built good houses and everything; they put in a train that was to go to Ensenada. They wanted to reach Ensenada with the train, to haul the flour and everything . . . Well, I'm not sure when that was because that is what people said. I don't know because I wasn't there at that time. But when we arrived, people told us that when the mill was in full swing they milled flour. We came because the German, Flick, got the contract to dismantle everything there.

Well, the German sent a letter to my father that he should take us to San Quintín to work there with him. He already knew me and my brother. Well, after we opened the letter . . . my father looked for some mules right away. He brought them and left them in San Quintín. It took us two days of traveling [about 192 miles] from Punta Prieta to San Quintín [laughing]. On mules!

When we arrived . . . he gave me and my brother a room and everything we needed to work. He had about ten or twelve men working, razing everything . . . dismantling and taking everything out.

Don Loreto stayed in San Quintín with the crew for six or seven months until the work was done. He worked as a blacksmith, making tools and various parts for disassembling machinery and for its shipping. Once the work was done, Don Loreto tells how the parts were loaded onto barges and hauled by small steamers out to a ship that would carry it all away.

The big ship that the company sent to pick up all the machinery stayed anchored outside . . . where it was deep; a ship of immense size. It came to pick up everything . . . from the shore two small steamers pulled the cargo by barge. They made only two trips per day . . . (2/18/76)

The ship took all the machinery that was inside the mill and the railroad track and platforms. [Laughing.] It took everything in only one trip! (2/18/76)

Once the work was finished, Don Loreto and his brother went north to San Diego, in 1910, and sent for their parents. The decision to move north was instigated by their boss, Mr. Flick, who had planned to take both Loreto and Doroteo to Los Angeles. But Don Loreto's immediate supervisor suggested that San Diego, where they had family, was a better destination. So they decided on San Diego, where they immediately sought out friends from the mining circuit.

We came in the Bernardo Reyes to Ensenada. We stayed there just four or five days with some acquaintances. From Ensenada we came here to El Cajon. My sister already lived here. She was the married one. (2/18/76)

When we arrived to San Diego we went to the home of los Castellanos. Narcisso Castellanos lived here, the father of the Castellanos who are from San Diego. He was already living in San Diego. We arrived there because he had always been very good to us and we were very close from down in Calmallí. . . . (2/18/76)

Loreto's old mining friend, Narcisso Castellanos, received them and took them out to El Cajon where Don Loreto's sister was living. Once settled the young men sent for their parents. Their mother and father also arrived on El Bernardo Reyes, never to return to Baja

California again. Don Loreto, however, was back in Punta Prieta before the year was out.

Life in the United States was not easy for many of the new immigrants. For Don Loreto, like others, the work was demeaning and the pay was bad, as he himself states:

And I didn't like it. The work here payed very poorly, very poorly. It was $1.25 a day. I worked with the water company of the district of La Mesa . . . you heard me mention that company . . . I worked making ditches with only a pick and shovel. For one dollar twenty-five [laughing]. A person threw his soul into that work. But I had very good work in Baja California with the boss, Mister Brown, who ran the business in Punta Prieta. Well, anyway I didn't like the work here, but I kept it up because my father and mother were here . . . They also came after we did on the Bernardo Reyes . (2/18/76)

San Diego in the early decades of the century was the major business center of both Southern California and the northern frontera. The small steamers commuted regularly between the Pacific port towns and a few went as far as the cape and across to the mainland. San Diego was still a major outfitter and center of negotiations for the business and mining efforts of the northern peninsula.

On a Saturday outing in San Diego, Don Loreto ran into his old boss's son, Kenneth Brown, who advised him of a new job his father had taken in Punta Prieta. Before the day was out, Don Loreto had contracted to work for Brown again.

I went to San Diego one Saturday night. Well, who for all my great sins, while I was in the store, I ran into my boss Brown's eldest son, Kenneth [Brown had two sons and three daughters] who was walking around the stores making purchases when I was shopping for shoes or I don't know what, when I ran into him there.

"What are you doing here, Loreto?" said Brown's son, the boss's son.

"Well, nothing, I came to look around," I told him.

"Listen," he says, "do you want to go to Punta Prieta?"

"What am I going to do there?"

"My father is going again to work the mines. We're getting

ready," he said, "loading the ship and it's going to leave in three days, the ship to Punta Prieta. Do you want to go?"

"Yes," I said.

That's how I responded. That "yes." And no one here in San Diego knew anything.

Then . . . he asked me: "Don't you want an advance?"

"Yes," I said. "Why not?"

Well, there we go.

"My father has the office close to the Grand Hotel. That's where he has an office. Let's go over there."

We went there right away and I greeted the boss, Brown. And Kenneth told him, "Loreto is going with us too."

"Oh yea, that's good," he said.

Then he gave me a thirty-dollar advance. Well, I was rich. In those days everything was cheap.

That same day, in late 1910, Don Loreto purchased his gear, then went to his old friend Narcisso and advised him of his return to Punta Prieta.

"Hey, listen, Chicho."

"What are you doing here?" I told him the whole story.

"Ah, that's good," he said.

I told him, "I'm going to El Cajon. And tomorrow I'll be back and I'm going to leave this suitcase here."

"Sure," he said.

Boy, I'm telling you. I came home in the early morning so that my father could see me. And ooo! He got madder than hell . . . He got very angry. He didn't want me to go. "No, I'm going to go," I told him. "The work here isn't worth it. I'm going to work for Brown." Well, if he wanted or didn't, in the morning that next day, I left. I went to San Diego on a small train that passed by El Cajon, early in the morning. And there I went, and that's how I left. (2/18/76)

Don Loreto returned to Punta Prieta with Mr. Brown where he worked for about two years. In Punta Prieta he married Ramona Rubio and then, along with Brown, went to the island of Cedros. On Cedros Brown had been contracted as manager of a copper mine. But the

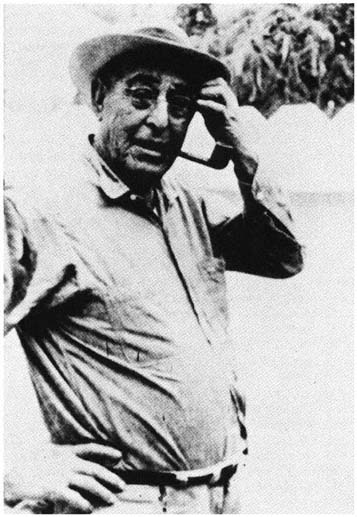

Loreto Marquez in El Cajon c. 1950. He turned twenty in 1900 while

working in the El Boleo mining concession granted to the French in

Santa Rosalía.

(Photo courtesy of María Marquez and family)

work there lasted only a short while (two years) and Don Loreto soon returned to the border again. His wife gave birth to their first child, and for their safety Don Loreto sent them to San Diego. He later joined them in 1914. Once back in San Diego, Don Loreto never left again for the south. His mining days were over, but for the next half century his closest friends continued to be those families he had met in Calmallí and the mining circuit.

The migration of los Smith, Castellanos, and Marquez through the mining circuit, from Calmallí to the frontera region, illustrates the beginning of the social relations that formed the basis of a network that was to last through the next half century. The life-style of the mines and the geographic points within the migration north formed a social landscape that was the basis for the interrelations of families and individuals making their way north. Throughout this migration these families demonstrated an internal social order that despite constant uprooting became progressively stronger as a result of the migration experience. Close ties were formed with new friends and kin, ties that outlasted even the first generation's offspring.

Various factors, including conditions in home regions, economic opportunities created by the mining booms, and changes in mine productivity, influenced the families' decision to move north and then across the border. People did leave the southern peninsula for better economic opportunities, but such moves were sanctioned by kin and friends who traveled with or received migrants in the host communities. Furthermore, in mining towns new relations were created providing greater security and further inducement for later travel north. As people traveled north, the desert towns and the work and social communities of the mines became a way of life, important in securing and producing new relationships. Calmallí was not just another mine, it was the mine and community where families met, shared births of children, social events, and friendships.

The final move to the northern border marked the end of the mining migration. Once established along the border, these families remembered the mines of the central peninsula, like their hometowns in the cape, as places important to their families for social relationships and as a basis for a shared recognition of historic, geographic, and social ties.