Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr.: Tapestry of Life

Interview by Pat McGilligan

No matter their résumé of accomplishment, the American (one is tempted to say "distinctly" American) scriptwriters Harriet Frank Jr. and Irving Ravetch have maintained a stubborn privacy. Throughout their careers, they have refused interviews and dodged publicity. The press kit for their most recent motion picture did not contain a photograph of them, and the studio was hard put to supply one. They make clear their preference to let the work speak for itself—and indeed, it is a formidible body of work.

At first, they worked, not as a team, but as lower echelon writers at MGM, beginning in the mid-1940s; then came salad days of studio assignments, westerns, and melodrama, up through the mid-1950s.

A team since 1955, they have consistently tackled difficult and unusual material. They have written provocative adaptations of William Faulkner's novels and dipped into the worlds of William Inge, Larry McMurtry, and Elmore Leonard. In their diverse screenplays, they have excoriated poverty, racism, poor labor conditions, and social neglect. Closely collaborating with the director Martin Ritt, they wrote an impressive run of eight quality features over thirty years.

Once a year, the Hollywood branch of the Writers Guild names a recipient of its highest accolade, the Laurel Award. Typically, only one Laurel Award is given annually. In 1990, Frank and Ravetch (together often referred to as the Ravetches) received that tribute of their peer group, joining the company of such previous eminences as Dudley Nichols, Robert Riskin, Billy Wilder, Nunnally Johnson, John Lee Mahin, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Preston Sturges, Richard Brooks, Samson Raphaelson, Paddy Chayefsky, and others—including Horton Foote and Ring Lardner Jr. in this volume.

Ravetch and Frank are the rare example of a Hollywood screenwriting team who met and married on the job, and not only have they stayed married, but in time they have become successful, as well as "very amiable," collaborators.

After a year of letters, phone calls, evasions and delay, in 1990 Ravetch and Frank agreed to talk about their careers. The interview took place at their hilltop home above Laurel Canyon in Los Angeles, filled with art, sculpture, fabrics, books, prints, and paintings. According to an admiring profile of their residence, "Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr.," by Michael Frank, in Architectural Digest (April 1990), the equal collaborators "part company when it comes to their house, which is filled with a varied collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European antiques, and is exclusively—

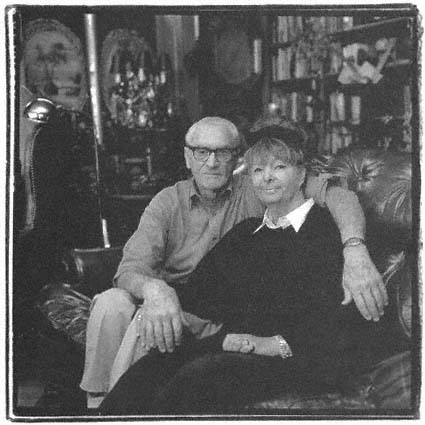

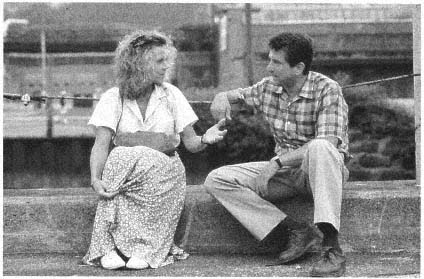

Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. in Los Angeles, 1993.

(Photo by William B. Winburn.)

and passionately—Frank's domain. Collecting has been her lifelong hobby. It began, like her love of movies, in Portland, Oregon, where her Aunt Beck ran an antiques shop. As a small girl, she fell in love with a Dresden rose jar, which her aunt let her pay off at ten cents a week."

Doubtless, the interview was like one of their writing sessions—the team disagreed vehemently at points, leavened disagreement with humor, finished off each other's sentences, topped each other's jokes.

This interview took place when their longtime friend Martin Ritt, director of their last release to date, Stanley and Iris, was still alive. "Since Stanley and Iris, " Irving Ravetch reported, "we've written an original screenplay on the life of Katherine Mansfield, but the world is apparently not eager to witness the story of a major short story writer who died an agonizing death from TB. For the moment, it joins some other unproduced work of ours on a shelf, but I do feel that one day its day will come.

The Difficult Family of Minnie Valdez, our first—and last—venture into the land of TV pilots, we shall not, at this moment, speak of."

Harriet Frank Jr. is always working on a novel, one of her "human comedies," and has published two to date. As for her husband, he has no interest in trying to write one. "I've never written any prose at all," Irving Ravetch said. "I have no sense of the rhythm or tone."

A collection of three of their best scripts was published in 1988, Hud, Norma Rae, and The Long, Hot Summer: Three Screenplays by Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr., with an introduction by Michael Frank (New York: Plume).

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Novels by Frank include Single and Special Effects.

Published screenplays include Hud, Norma Rae, and The Long, Hot Summer: Three Screenplays by Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr.

Academy Award honors include Oscar nominations for Best Screenplay for Hud (adaptation) and Norma Rae (adaptation).

Writers Guild honors include nominations for Best Script for The Long, Hot Summer and The Reivers, and the award for Best-Written American Drama for Hud. The Ravetches received the Writers Guild Laurel Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1988.

Harriet, you got your start through your mother, who worked at MGM in the 1930s and 1940s. Her name was also Harriet Frank? . . .

Frank: She was a story editor. That's why I'm Jr. She functioned as an editor on a lot of scripts, and she was consulted by a lot of directors.

Ravetch: She was a Scheherazade. Obviously, [the studio executives] Louis B. Mayer or Eddie Mannix were very rough types who did not sit down over the weekend to read Crime and Punishment. Her job was to read these immense novels and find the movie story in them, roughly, and then tell an hour version to the whole [production] board, so they could decide whether to buy the book and make the picture. She was brilliant at it. I know for a fact that six months later a producer would call her, having gotten stuck on the third act of some script, and say, "Could you come back . . . do you have your notes on the original story you told us?" She would review her notes, come down, and tell the story again, and they would straighten the script out.

What was her background?

Frank: She did some short-story writing. She had a radio program in Portland, Oregon, during the Depression. She was a lecturer. Very bright. And a very good editor. When the Depression struck, she came to California and got involved with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a story editor.

And brought you along?

Frank: Nepotism.

What about your father?

Frank: He was a shoe business tycoon.

Tell me a little about your parents, Irving.

Ravetch: My mother was born in Safed, in Palestine. My father was born in Berdichev, a town which is famous for its Jewish mystics, in Russia, in the Ukraine. I was born in New Jersey.

Frank: And your father was a rabbi?

Ravetch: I was a rabbi's son. I learned how to write, because a poor rabbi mobilizes his entire family to help. My job was to write bar mitzvah confirmation speeches for the young men when they reached thirteen. Each speech began the same way, I'm afraid: "Today, I am a man . . . "

How did you get to the West Coast?

Ravetch: Because I was dying of asthma. I had double pneumonia every single winter in the East, and the doctors told my family to get me out here, either to Arizona or California. They chose Los Angeles.

You both attended UCLA?

Ravetch: We went to UCLA at different times. Hank and I—Harriet—actually met at MGM. MGM was so fabulously wealthy that they could afford to run what they called a Junior Writing Program, in which they literally trained junior writers. There were thirty or forty of us.

How long did that program last?

Ravetch: It lasted for years. Hank was a junior writer; I was a short subject writer, which was quite a good training. Please make that distinction [between us]. For example, there was a short subject series I worked on called Crime Does Not Pay . . .

Frank: Talk about a checkered past . . .

Ravetch: Out of which came people like [the actor] Robert Taylor. After our training period, we graduated to being senior writers, almost imperceptibly. It was [the producer] Pandro Berman who gave me my first chance one day, harnessing me with an older writer on a project called Before the Sun Goes Down. This was the MGM prize novel of the year [by Elizabeth Metzger Howard (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1946)]. So fabulously wealthy was MGM that the studio would select what they considered the best novel of the year and award it a prize: their version of the English Booker prize. This year—I think it was '45—it was Before the Sun Goes Down. That was my first major screenplay and my first job as a senior

writer, in collaboration with an older man, Marvin Borowsky—a fine fellow, a good writer.[*]

Did Borowsky actually teach you things, or was it more a case of learning by doing?

Ravetch: Learning by doing. He treated me as an equal.

What had you been studying at UCLA?

Ravetch: English lit.

MGM officials would roam through UCLA and pick out interesting people?

Ravetch: They had some method of scouring the universities to find likely young people, but as Hank says, she got her job through nepotism, pure and simple; she makes no bones about it. I got my job because I was already a pretty proficient radio writer. After I went to college, my asthma got me out of the army, and I got my first job at KNX radio station, around 1942-ish. I wrote patter for western singers—for between numbers.

Frank: What a sordid past you—we—have . . .

Where did you meet? At an MGM story conference?

Frank: Aw, it's very romantic . . .

Ravetch: You want the story? I saw this lovely creature, and she was up the hall, about fifty yards. I knew a chap in the office next to her, so I went to him and said, "A deal: I give you fifty dollars, you give me your office." He said, "Done and done." So I paid for the office next to her and courted her on L. B. Mayer's time.

Some writers I've spoken to say that the writer's table at MGM was bunk; others say it was glorious hobnobbing. Which was it?

Frank: It wasn't the Round Table, I can tell you.

Ravetch: Neither of us were at the writer's table very much. We were talking marriage, so we went off the lot practically every day.

Frank: I remember some common agonizing about how we were overlooked and [how] our vast talents were underexploited.

Ravetch: We bitched a lot.

Frank: And we played word games a lot. There was a sort of camaraderie.

What kinds of things did you work on as a junior writer? Did you often work in tandem with senior writers?

Frank: No. The studio would just hand you scripts and say, "Do something about the dialogue," or "We're not satisfied with the storyline." Since we were

* Among Marvin Borowsky's screen credits are Pride of the Marines and Big Jack, Wallace Beery's last film. According to Variety, before coming to Hollywood in 1940, Borowsky worked for the Group Theatre as stage manager for Elmer Rice, and for the Theatre Guild as playreader.

all underpaid and eager, we took whatever was handed to us. We worked on many scripts—sometimes with credit, sometimes without. Finally, when we got slightly long in the tooth and beyond the status of juniors, then we announced, "We're no longer junior writers. We think we are senior writers and should be paid the minimum."

MGM said, "That's fine . . . "?

Frank: No. The studio fired both of us. When we came back from our honeymoon, we were out of jobs. I went in and asked them why. Well, they said it was "economics," and so on. I said they hadn't read any of my scripts and it was reprehensible, and I walked out. They were deep-sixing the whole program.

Ravetch: They were retrenching.

Frank: They do that periodically while they are building an extra swimming pool for themselves. It wasn't until I went to Warners that I was really considered a senior writer. After being fired, I got a job as a full-fledged adult writer at Warner Brothers, and Irving . . .

Ravetch: For a period, I just stayed at home and wrote original western stories.

When you were in college, studying English literature, what were you thinking of doing—was it always movies?

Ravetch: Absolutely. I was hooked on movies from the age of seven, from the time I saw The Cisco Kid with Warner Baxter. I knew I had to be in that world. It was a siren song.

You weren't going to act or direct—you were always going to write? It was that cut and dried?

Ravetch: There was a long period when I was going to be a terrific actor—and a playwright—but movies were always part of the equation.

For you, Harriet, it was more of a natural progression?

Frank: I think so. I was led to it because of my mother.

Ravetch: Harriet was a very good short story writer, early on—and wrote upwards of one hundred stories for the Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, and other magazines. She kept me alive during the early years of our marriage.

What kinds of stories did you write, Harriet?

Frank: Comedies. I don't know how I moved from comedy to stories of social conscience . . .

The short stories were something you did to stay alive professionally after leaving MGM?

Frank: I did a little short story writing on Warner Brothers' time. At Warner Brothers, I had to write tough dialogue for a fight picture with Dane Clark [Whiplash ], and cowboy talk for Errol Flynn [Silver River ]. Strange jobs got offered to me at Warner Brothers—but serious and well-paid jobs, too. I pursued them for a while. Then, as I did more screenwriting, I did less short story writing.

How did you get typed or channeled, early on, into westerns?

Ravetch: That may have been my doing, because the western landscape moved me, even as a child. Maybe it was the grim, bitter, eastern winters as opposed to the sight of that glorious sunshine flooding the plains, which I saw in the movies. I wanted to try westerns, and I did. For a long time, I wrote only western originals and had no interest in doing the screenplays. Just sold the original stories. And I was also trying to do a play.

On Broadway?

Ravetch: I did try, two or three times. Bombed, ferociously.

Why did you have that schizophrenia—writing westerns on the one hand and Broadway plays on the other?

Frank: It's called making a living on the one hand and aspiring on the other. (Laughs. )

Ravetch: Also called working . . .

Frank: When we formally decided to collaborate, we left westerns behind.

What about Ten Wanted Men, Run for Cover . . .

Ravetch: Vengeance Valley . . .

Those were all westerns, right?

Frank: Let me put it to you this way: we weren't very picky in those days. What was presented was written.

Ravetch: (Laughs.) Right.

How many years had gone by before you started working on every script together?

Ravetch: We didn't collaborate for the first ten years of our marriage.

What led you into collaboration?

Frank: Affection and loneliness.

Sometimes that can lead people away from collaboration.

Frank: He would go down the hall to one room, and I would go to another, to be confronted with two sets of problems. Suddenly, one evening, we said to each other, "This is nonsense. Let's try it together." Happily, we've been doing it ever since.

Ravetch: It was a happy decision.

Frank: It's a very amiable collaboration.

Were you learning gradually how to become storytellers? Was it a developmental process? Was this the point in your careers when you felt you had it?

Frank: (Laughs. ) Not then, not now. I don't know . . . how does anyone learn their craft? It's like learning to swim: you get thrown into the swimming pool, you paddle around and nearly drown, you reach for the side, and eventually, you learn.

Harriet's primary influence was obviously her mother. How about for you, Irving—something that was imprinted upon your storytelling?

Ravetch: My influences were Noël Coward, George Bernard Shaw, Ferenc Molnár, and [Henrik] Ibsen, because I wanted to write plays. I studied them

very, very carefully, took them apart, and put them back together. I read them, studied them, acted them, and used them.

Do you still refer to them in your thinking nowadays?

Ravetch: No. That's part of another life.

Frank: That's for pleasure.

Does that list stimulate any comparisons for you, Harriet?

Frank: I was an English major, and I loved to read. I'd like to say Jane Austen was an influence, but heaven forfend that I should do so. It's just the things that pleasure you as you read . . . I don't know that you learn your craft that way. I have a sense that we were thrown into the studio system, and we went by the seat of our pants, by instinct, and by a modicum of luck and happy circumstance. It's all very up for grabs.

Were there veteran Hollywood writers, early on, that you either admired or talked to, who seemed to you to be exemplars?

Ravetch: We liked foreign movies a lot. I preferred French and Italian movies to American movies, because I think our interest lies mainly in character, rather than in driving the story forward.

Frank: Foreign movies seem to take the time to pause and discuss the ambiguities and complexities of life, whereas American producers were always telling us—

Ravetch: "Keep your film moving . . . "

Frank: Always telling us, "Get on with it . . . "

Ravetch: So that so much was lost. It was an impoverished form for us, in many ways, the [American] movies of the 1940s and '50s.

Frank: Whereas we loved [Ettore] Scola, [Vittorio] De Sica, [Marcel] Pagnol, [Ingmar] Bergman.

Ravetch: I think our favorite movies are most like novels. Oblomov [a 1980 Russian film, directed by Nikita Mikhalkov] is a good example.

Frank: My Life As a Dog [1985], a recent one, was meandering—it didn't have any immense story thrust—but it had a marvelous sense of worldview from a child's perspective.

Ravetch: The equivocal, the undefined . . .

Frank: It had a tapestry. It would pause. It didn't have to fall all over itself. It just presented itself, the way a novel does.

That's certainly one of the things that is wrong with this generation of Hollywood scriptwriters. Your generation of screenwriters was more literate. They were bookish. They knew books, read books, and loved books.

Ravetch: I must tell you that I personally, have a difficulty with the idea of movies—which I can't call films, incidentally—being an art form at all.

Frank: I don't. C'mon!

Ravetch: When one examines the Russian novels, the Victorian novels—Faulkner—I have a problem.

How about when a film is derived from a wonderful book and is a perfect adaptation?

Ravetch: It lacks the language, the force, and the mystery.

Frank: I don't entirely agree. I have had experiences watching movies that I feel are as artful as a novel.

Ravetch: Harold Pinter wrote an adaptation of Marcel Proust; it would make a good movie, but it can't give you the same sense of the enigma of life.

Frank: No, but what is the French film you adore so—La Grande Illusion [1937]? That is as textured as a novel. So was Wild Strawberries [1957] and some of Scola's movies—Bread and Chocolate [1973]. There are a lot of movies that for me carry the weight of a novel.

In John Huston's [ An Open Book (New York: Knopf, 1980)], he says that a very good script, the actual script itself, if it is well written, can be read as literature. That the script, in and of itself, is a valid form of literature.

Ravetch: I agree.

Frank: And he made a movie which I admire greatly—which had the richness of a novel—The Dead [1987]. A remarkably subtle and layered and textured film.

Once you began to collaborate, there was also a quantum change in what you began to try to do—in the kind of material and the ambitiousness of the projects. Is that partly because the studio system was collapsing, and you had to separate yourselves from the system and find other things to do at that point?

Ravetch: I think it's precisely because we did start working together . . .

Frank: And because we started working with Marty [Ritt] . . .

Ravetch: And whatever faculties we had, we combined into a fresh view.

Would it be fair to say that your talent was also maturing at that time?

Frank: You won't hear me say it!

Ravetch: I know my body was maturing.

When and where did you meet Marty?

Ravetch: When I went to New York on one of my abortive playwrighting forays, a producer optioned a play of mine and gave me the choice of two directors. I picked the one who was not named Marty Ritt, and then the play turned out a terrible failure. Ever since then, I felt, "I have got to make this up"—to myself—not to Marty. So, when I came back to LA and we embarked on our first major feature with Jerry Wald at Fox—The Long, Hot Summer —I recommended Marty Ritt.

He had already directed Edge of the City [1957].

Ravetch: Right. So there was no question, or any problem, about getting him hired.

Frank: Jerry Wald, bless his heart, took us all on.

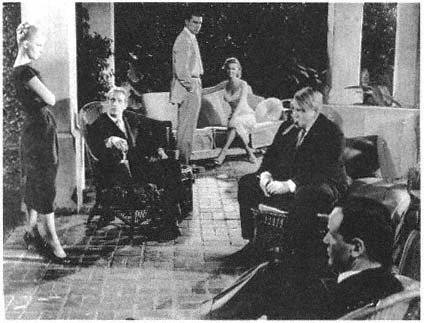

"Ten percent of Faulkner": from left, Joanne Woodward, Paul Newman, Anthony Franciosa,

Lee Remick, Orson Welles, and Richard Anderson in The Long, Hot Summer.

Wasn't Marty still on the blacklist, especially on the West Coast?

Ravetch: That problem almost immediately surfaced. I remember the day Marty took us aside and said, "Fellas, I'm not going to be able to make the picture with you. They want me to do something I'm not prepared to do." He went back east. But somehow it was straightened out very shortly thereafter, and he returned.

What was the nature, then, of your rapport with Marty?

Ravetch: The same as it was later. The immediate recognition that we were dealing with a man of principle, a man with a wonderful mind, a man who was absolutely honest and direct, a man with terrific energies and skills and abilities—to which we responded immediately. We were able quickly to learn how to speak to him in a kind of shorthand. Very shortly, Marty became like a big brother to us. He fought a lot of our battles for us. We were a gang of three.

I gather Marty was unusual to the degree that he protected his scripts—and scriptwriters.

Frank: He always protected ours. He always was very stalwart about his writers, very sympathetic to the point of view of writers and their contributions.

Did you know instantly that you were also getting a director who would prove so sensitive to actors, who would be so complementary to scripts like yours that are so attuned to characterization?

Ravetch: Yes.

Why? Was it in the air?

Frank: It was in the man. First place, because he was an actor himself, he was very sympathetic to actors, very attuned to actors, and very patient with actors. Any impatience he felt anywhere else in the world disappeared when he was working with actors. Marty was infinitely patient with actors. He was that way about writers. He was not an attack-and-destroy director where writers are concerned.

Ravetch: We've been very, very lucky. There's a little heresy involved in a screenwriter paying tribute to a producer—there have been some long, bitter fights and strikes against producers—but people like Pandro Berman, Sol Siegel, and Jerry Wald were also men who had high regard for the written word.

Frank: They were all marvelous.

Even Jerry Wald? I have heard a lot of horror stories about Jerry Wald . . .

Frank: Most particularly, Jerry Wald. Jerry Wald took a chance on us, inexperience and all.

Ravetch: More than that, we did not have the harrowing experience with him that many screenwriters did—doing seventeen versions of a script.

Frank: He wasn't in the least difficult. He was supportive.

Ravetch: I had met Jerry when he was head of production at Columbia. This was before I began collaboration with Harriet. He assigned me to do D. H. Lawrence's Sons and Lovers. As a result of that abortive experience—because that picture wasn't made until many years later, under a different script and different auspices—he was willing to take another chance.

He treated us very well. He bought the novel of The Hamlet, by Faulkner, for us. The script we turned in bore no resemblance to the book whatsoever, and he went along with that.

Did he know the difference?

Ravetch: Oh yes. We're discussing an intelligent man. He read the book and the script and the notes and the revisions—everything.

Frank: We found him very surprising—because we knew the reputation, too. He was steady, he was supportive, he fought the fights that had to be fought, he functioned as a good producer.

Ravetch: Absolutely.

Why did he come to you in the first place with a Faulkner book?

Ravetch: We brought the novel to him. Now, mind you, here's a book in which is delineated, possibly, the most evil and vicious character in American literature—Flem Snopes. We turned him around into a romantic hero.

Frank: No, no. Ben Quick was the hero . . .

Ravetch: But Flem Snopes became Quick . . . who became Paul Newman. We made him a romantic hero, so that our story would work. A pretty desperate thing to do to Faulkner. When the picture [The Long, Hot Summer ] was finished, we asked someone traveling to Jackson, Mississippi, who knew Faulkner, to ask him, with some trepidation, what he thought of it. Faulkner said, "I kind of liked it."

Frank: America's greatest writer of pure fiction.

Ravetch: The novel has fabulous elements. The character of Will Varner—the forerunner of Big Daddy—is very interesting, powerful, and all-encompassing.

Frank: The book is full of vitality.

Ravetch: There's a section in the book, which was later published as a story called "Spotted Horses," which is one of the most hilarious pieces of American literature.

Frank: Faulkner was uniquely gifted. Also, because he had been a screenwriter himself, he was a very tolerant man where other writers were concerned. He knew what laboring in the field was like. He was very realistic about letting go of his work.

Ravetch: And in spite of all the horrors we wreaked on that wonderful book, the film worked.

Did all of your Faulkner adaptations originate with you?

Ravetch: We brought The Hamlet to Jerry, The Sound and the Fury to Jerry, and The Reivers to Gordon [Stulberg]. Yes, they originated with us.

Many of our adaptations made violent departures from the originals. We began with The Hamlet and ended with The Long, Hot Summer. Possibly ten percent of Faulkner is in that movie. The only really pure adaptation we ever made—except that we invented a second act—is The Dark at the Top of the Stairs [from the William Inge play].

How about Hombre [from an Elmore Leonard story]?

Ravetch: Fairly faithful.

Frank: Pretty close.

Ravetch: The Reivers is pretty faithful, too. But with Hud, two key characters were invented: Hud himself is a minor character in the novel and is our major contribution: Alma, too, became an original character. Much of the time, we're doing a hybrid form, it seems to me. They're not adaptations, they're not originals.

Was it serendipity that Marty also happened to be fascinated by the South? And to admire Faulkner?

Frank: When we came to Marty with high enthusiasm for anything, he'd pay attention. Usually, we were on the same wavelength. In the end, we found eight subjects that we liked together. Whenever we were stirred by something, he very quickly responded.

Was serious drama, for some reason, an expression of yourselves that was more basic and truthful?

Frank: All my life, I've seen myself writing comedy. When I wrote by myself, I wrote comedy. Somehow or other, maybe related to Marty in some way, I did go into drama.

Ravetch: The various pieces by Faulkner led us to the South, and the South is the landscape where the greatest evil committed by Americans occured. It's also where there was a terrible, bloody war. So it's full of memories, an indelible, brooding, phantom of a place.

Frank: The issues that interested Marty also interested us—

Ravetch: And vice versa. We have our own social concerns. After all, Hud dealt with the greed and materialism that was beginning to take over America, and which has fully done so today. Conrack and Hombre dealt with racism; Norma Rae with the exploitation of the working man, of a great industry that so long resisted being unionized.

Frank: Those stories are just strong stories, and they also make a social comment, which we are not ashamed to make.

Ravetch: We searched out the strongest material we could find.

Frank: We sought the issues that in each instance said something important to us, or that we felt drawn to.

But it stacks up in a certain way. Marty said to me once that he liked projects with interesting characters and a good story, of course—but there had to be that extra edge.

Frank: I think we'd say the same.

Are there pictures of yours—whether directed by Marty or not—that you feel particularly fond of, or that worked out from beginning to end, very much the way they ought to?

Ravetch: Hud, Norma Rae . . . Conrack, I enjoyed . . .

Frank: I was happy with The Reivers, too . . .

Ravetch: The Long, Hot Summer— except the ending, which was imposed on us.

Frank: That happens too.

Ravetch: But we deserve the blame. Our name is on it.

What was Marty's usual involvement in the script in the initial stages?

Frank: He waited, unlike most directors. He waited and let each person do his job. He didn't have to wait too long with us. We're not too slow.

Ravetch: We're ten-week writers.

Frank: Fourteen, at the top.

Ravetch: Over the years, ten is our average.

Frank: Marty left us alone. He was a dream director for the screenwriter. That's not common.

If, after the first draft, there were problems, then what?

Frank: If Marty wanted changes, he said so—directly. He was very specific.

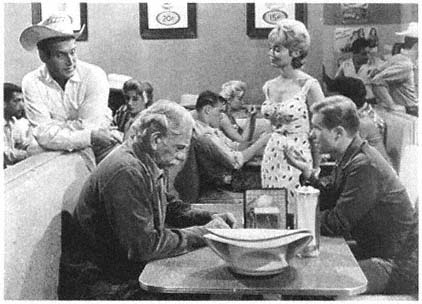

From left, Paul Newman, Melvyn Douglas, and Brandon de Wilde in Hud.

Ravetch: I must tell you that there's not been a lot of fussing with our scripts. Primarily, there is always cutting. Twenty percent is cut.

You mean you have a tendency to go on too long . . .

Frank: No, we have a tendency to come in at 120 pages, and Marty liked to shoot 100 pages, which made for a two-hour movie. So his rhythm was perhaps slower. But we did not do a lot of rewriting for Marty.

Ravetch: We have been very lucky. We have been lucky in the producers I mentioned. We've been lucky in the directors we have worked with—Mark Rydell, Vincente Minnelli, Delbert Mann, Marty Ritt, for sure. And we've been lucky in the actors we've had. Paul Newman—a good citizen. Sally Field and Jane Fonda—decent people. Patricia Neal—a superior woman.

Frank: I don't think we ever ran into an explosion of temperament. (Pauses. ) Maybe [Steve] McQueen . . . briefly.

Ravetch: It's hard to remember. We've not done a lot of rewriting. There was one occasion—when we turned in a script to Marty—and he said, "It's not dramatic." Failure! Fifteen weeks' work, and it's no good. We knew exactly what he meant, and we knew he was right. We ran out of the room and came back with another script six weeks later. Presumably, it was dramatic, because it was shot.

Frank: We can't tell you a lot of horror stories.

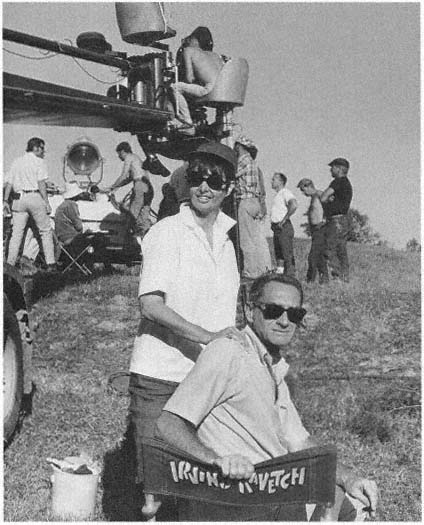

Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. at work on the set of The Reivers.

(Courtesy of Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr.)

Which script was that?

Ravetch: I think we'd better not say.

Frank: Nosey! (Laughs. )

With Marty, were you always on the set?

Ravetch: With Marty, we were on the set throughout the shooting.

Frank: Always.

Ravetch: We were there before the picture started, and we were there during postproduction. Marty Ritt had such a strong sense of himself—he was unthreatened by the presence of writers at his side.

If the script was being filmed just as you wrote it, what did you do on the set after all?

Ravetch: (Laughs. ) Not much . . .

Frank: At night, we'd talk together about the work, the performances, how we felt the movie was shaping . . .

Ravetch: Various things come up; changes are dictated by the momentum the picture achieves as it forms.

What is your relationship to the actors vis-à-vis the script?

Frank: If they had questions, they asked Marty.

Is there a wall between you and the actors?

Frank: That's not where writers belong . . .

Ravetch: The director insists that you don't speak to the actors. The chances of causing confusion arise. That's really infringing on his responsibility.

What kinds of things were you discussing at night with Marty? Physical blocking and action? . . .

Frank: No. That was really Marty's balliwick. But he would discuss with us what he hoped to achieve in a scene or its shading and shaping. It was very much like the conversations, I think, that go on in the theater between a writer and a director. It's not adversarial. It's about the work in general, and how it progresses. It's comforting to writers to have a director's ear, and in Marty's case, I think he liked having his writers there just as part of the creative process. But as far as directing is concerned or crossing the line with actors, that's really not appropriate.

I think actors sense that, about writers being present. They know that a director is actually in control of that set, of that picture. In a way, our work is done, unless something comes up that makes the actors extremely uncomfortable, and Marty says, "What can we do to help them?"

Was there a feeling around town, for a time, that you were joined to the hip of Marty Ritt?

Ravetch: No. But when we have taken other jobs and been on other sets, people have said to us, "Did Marty Ritt let you off your leash?"

Frank: We're for hire.

Ravetch: Happily!

Frank: (Laughs. ) When something's offered.

Ravetch: Norma Rae was one—it came to us from producer Tamara Asseyev.

Frank: There, again, we had producers who were very supportive. We ran into lots of static about using actual factories and the antagonism to the company coming on location [to film] and big mounting costs, but [the 20th-

Actress Sally Field going over a scene with director Martin Ritt for Norma Rae.

Century-Fox executives] Alan Ladd [Jr.] and Jay Cantor were stalwart. They stood with us shoulder to shoulder—they were marvelously supportive—men of their word. When Ladd commits to you that he is going to make a picture, he makes it, and he stands by you while you're making it.

Ravetch: Murphy's Romance was another one—Sally Field brought it to us. Stanley & Iris was brought to us by [the coproducer] Arlene Sellers. In fact, the last three pictures were assignments . . .

Frank: But it's very hard for us to get married to material. It seems to be much easier if we find something on our own that channels our energies.

What is the reason why the credits stretch out between Norma Rae and Murphy's Romance? . . .

Ravetch: Perhaps it indicates that we haven't been as enterprising of late as we were early on. We have an original which we sold to Warners, but they couldn't cast it or make it. It was called "Mixed Feelings." We have our share of pictures that aren't made.

Frank: Along with every other writer in town.

Is that an occupational hazard, or is that an occasional source of sadness or tragedy?

Ravetch: An occupational hazard.

You can shrug the failures off?

Ravetch: Oh, absolutely.

Is there any other reason why the credits slow down?

Frank: It's simply getting tougher because our subject matter is not always the kind that will strike management as being highly commercial. You have to find somebody who takes an act of faith in making a movie with you. Then there's a certain degree of just living your life—movies being one part of it— but the pleasures of life being another. As you get on in life, you want to do many other things . . . now, can I get angry and hold forth?

Ravetch: Go ahead.

Frank: I think there is a very nasty undertone in American life, where the appetite for violence is out of control. I think films cater to it shamelessly, and it feeds into irresponsible social behavior. I think that the time has come where, once in a while, whether audiences respond to it greatly or not, it is necessary to propose a different standard. It's become a sort of basic tenet of American entertainment: super violence.

Ravetch: We made a really terrible mistake with a picture called The Cawboys, in which John Wayne was killed, and the young boys who were in his charge avenged his death. The picture was never shown in some countries. I think that could happen on a more widespread basis in the Common Market in five—ten years. That will quickly put an end to the making of those kinds of motion pictures.

What do you mean, "a terrible mistake "? A terrible box-office mistake?

Frank: No. We made a terrible moral misstep, because the film shouldn't have ended that way.

Ravetch: The kids could have captured the villains and brought them in for trial. It was not necessary to have the children going out with guns and doing the killing.

Was that in the original source material?

Ravetch: No. That was our contribution. The source material had them round up the villains and bring them all to justice.

That's something you regret?

Both: Absolutely.

Ravetch: That's a major regret.

With all the present-day obstacles, do you have less of a drive to surmount the obstacles and write films?

Frank: No, I'm full of beans and vinegar. I'll take on anybody my weight, any place, any time. But at this point in my life, I don't want to do anything that I don't delight in, one way or another. Either I want to feel passionate about it on a social level or get an immense kick out of it.

Is there a reason that in the last ten to fifteen years—or at least, beginning with Murphy's Romance and continuing through Stanley & Iris—you seem to be moving away from dramatic material and getting into more romantic situations?

Frank: Maybe it's the September time of year, psychologically or emotionally. It's not that you lose your passion for social problems, but there's a deliciousness that you want to experience writing, too. Laughter is certainly part of that—an immensely gratifying part.

What is the history of your most recent film, Stanley & Iris?

Frank: It came from a wonderful book by an immensely talented writer, who is an English schoolteacher [Union Street, by Pat Barker (New York: Putnam, 1983)]. It is a very different book from the film. Her book is a story of poverty and of a group of women who live in really crushing northern England poverty—in which poverty is the enemy and the obstacle for their lives. One of them in the book is married to a man who is illiterate. It's just touched on very lightly in the novel. It is a many-character novel with varying stories—rape, marriage, being elderly and abandoned.

In this book, there is one character, Iris, who is the strong central character. She is a touchstone for the other people. Her husband happens to be illiterate. That, because it is a subject that interests us greatly, seemed to make the project very worthwhile. That was an issue we wanted to fasten on, something we found very important and moving. So we made that the focus of the story.

Who brought the book to your attention?

Frank: Alex Winetsky and Arlene Sellers, who produced it. They had found the book in England.

"An important and moving issue": Robert DeNiro and Jane Fonda in Stanley & Iris.

Did they have in mind doing what you eventually did with the story?

Frank: No, this was a small element in a much larger canvas. The book was beautifully written; the author is supremely gifted. It appealed to us on that level.

Why did they decide to come to you?

Ravetch: They knew us, and I suppose they knew we have done pictures of this kind before.

How hard was it to get people around town committed?

Frank: Not hard—because Alan Ladd is courageous. And, as we say, when he says he will do a subject, he does it.

How crucial is it, doing a picture like Stanley & Iris, to get the cooperation of people of the stature of Robert DeNiro and Jane Fonda?

Frank: Very. It would be difficult to get the film off the ground otherwise.

At what point did they commit to the project?

Frank: After the script was written.

Therefore, they had no real input into the script.

Ravetch: No actor that we've ever known has had any input into the script, with the exception of Sally Field in Murphy's Romance. She was, after all, the producer.

That's remarkable.

Ravetch: When you think of people like Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino, yes, that's remarkable.

Vincent Canby in the New York Times was one of several critics who commented negatively on the ending. What happened there?

Frank: We had what I considered a kind of delicate, offhand ending to the film, which was romantic but didn't tie everything into a neat package. The preview audiences were bewildered if they couldn't see the two characters go off into the sunset together—where, in point of fact, did they go? So we wrote a more specific ending, and I regret it because I think the original one said all that was needed.

Aside from the ending, is what you see up on the screen what you envisioned?

Ravetch: I like the movie.

Frank: My annoyance with the critics is I hate to have what the picture is talking about lost because of their carping. It's an immensely important issue because one out of four Americans can't read.

The things that went awry, went awry. I still think it's a good love story. The two people are very attractive; they're not beating each other up; they have some human concern for each other. I'm not ashamed of the movie. I would do it again.

Ravetch: Amen.

Let's say you're starting a new script. I'm a producer. I've just brought you a great book. You've read it and agreed to adapt it. Now you're going to start. What's the drill? What time of day do you go to work?

Ravetch: We work off the first rush of energy. Nine to one. I sit at the typewriter. Hank paces. We have already made our outline of thirty-five or forty-five major scenes, all on one page.

Who does what? Who starts the ball rolling?

Frank: Who knows? It's really pretty seamless by now.

Early on, was one of you the senior partner; the other, the junior partner?

Both: No.

Does one of you have relative strengths in terms of the characters or the overall arc of the story?

Ravetch: I don't think so, the proof being that when we're finished it's often hard to distinguish who wrote what.

Frank: It's even-steven.

Ravetch: It's really a pure collaboration in the sense that we get together; we talk out problems at great, exhaustive length; we do some kind of an outline together; and every word really is collaborated on. Every word is thrown up in the air for approval—from one to the other. The script is not so much written as it is talked onto the page.

The outline has already been made over the course of a longer period of talking about the story back and forth?

Ravetch: Yes, yes. Everything flows from three to five weeks of really absorbing the material and talking about it. Going for long walks, long car rides, with pads, making notes, writing furiously behind the wheel, having car wrecks.

Do you think about things like—the story is interesting, but it needs an exciting set piece here, a fresh location there? . . .

Ravetch: I'm sure that concerns us early, during outline time, but what really concerns us is that the story is organic, cohesive, that it builds . . .

What are you thinking about principally?

Frank: The people.

Ravetch: Really, of the individuals, all the time.

Frank: Who they are, what their emotional push is, what would bring them into conflict. Their behavior.

Do you write down detailed things about the characters in terms that we never see on the screen?

Ravetch: No. We just try to know them thoroughly.

You're always just putting them into the situation?

Ravetch: We put them into the situation, the event, the conflict. How do they respond? What is their behavior, their complexities, their ambiguities, their paradoxes? Why do they differ, why do they perplex each other?

How they speak differently from each other?

Frank: That comes when we're actually writing. We don't really think about that in the initial stages, because we talk dialogue back and forth to each other [when we are writing], as if we were actors, and that's the method. We're closet actors. I'm terrible, he's good.

Okay, you start on page one. How far do you get in a day? One page, if you're lucky? . . .

Ravetch: If we're lucky, we get two. Two on the average. Three would be a fine day. It's possible that we do the three pages and then redo them again. Often, by the end of the day, we've really done three or four revisions of what amounts to the same three pages. So that by the time the script is finished, it has gone through a number of revisions.

So your first draft is very polished.

Ravetch: It is polished.

Frank: We revise as we work on our first draft—constantly. By the time we've arrived at that final page, we have gone over the script many, many times.

Do you brook any interruptions?

Ravetch: No. It's a sacrosanct period. We are very disciplined. It's an inviolable time. There are no interruptions. Beyond that, it's unthinkable that we should take a workday off. We go at it five days a week.

For the average often weeks?

Ravetch: Correct.

Is the phone on?

Ravetch: No, and if it's on, it's not answered.

Are you drinking coffee?

Ravetch: No.

No one is ever here? Marty was never here?

Ravetch: No one is here. We couldn't work with anyone in the house. With us jabbering at one another?

What happens at noon or I P.M.?

Ravetch: Whew. A good day's work.

You go off and play tennis?

Ravetch: That's right.

Frank: No. We read it over, we think about it, we talk about it. There's a little pad beside the bed at night. Lots of dinner table conversation relates to it.

Ravetch: It's true; we do go out to dinner at night with a pad and talk over the next day's work. To get a running start.

Do you have any tricks to get started the next day?

Ravetch: We don't do what Hemingway did, which is to stop in the middle of a sentence at a very good point.

Frank: I don't like to leave the day's work in disarray. If there is something that's troubling us, I like to stay with it until it's reasonably in place to be looked at with a cool eye the next morning.

Then . . . the next morning?

Frank: We begin by reading the day's work before.

Ravetch: Just read it to ourselves.

Frank: And if there's something disturbing, we go back, then and there.

When is your best thinking done?

Frank: Bathtub, for me.

Ravetch: At work. Because that energy's precious.

Frank: I'm inclined to brood when the work is done.

Ravetch: We do brood, of course: But the best work is done at the typewriter, as it happens.

How do you know when it is right?

Frank: When does anybody know it's right? C'mon!

Ravetch: It's a click.

Frank: I don't get any clicks.

You're tapping into the unconscious to begin with, so how do you know?

Frank: You make the best and most judicious appraisal of the work that you can; and you're either right, or you're wrong.

Ravetch: That sounds too judicious to me. You know because you're a professional and a craftsman.

Is the work joy or anguish?

Ravetch: The plain truth? Joy.

Frank: We like to work.