2

The Postwar City, 1945–1966

St. Petersburg, Petrograd had gone for ever. This was Leningrad. It had inherited many things from the other two, but it had its own substance, its own personality. . . . One no more felt like calling Leningrad "St. Petersburg" or "Petrograd" than one felt like calling Stalingrad "Tsaritsyn."

—Alexander Werth, 1944

Reconstruction

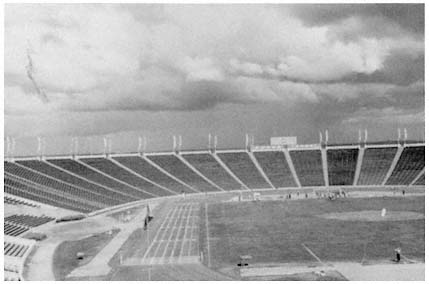

After March 1943, the city's fortunes began to improve, and the Finno-German blockade was lifted in January 1944. Later in 1944, when the city was fully liberated, the State Defense Committee in Moscow announced a plan for rebuilding Leningrad.[1] Recognizing that the population had fought and died for their "Peter," as residents affectionately called the city, the framers of the 1943–1947 reconstruction plan abandoned the previous effort to shift the city core southward and reasserted the primacy of Leningrad's historic center. For example, October 30 Prospekt once again officially became Nevskii Prospekt (while International Prospekt was also renamed, in honor of Stalin).[2] In 1945–1946 more than 700 million rubles were invested in the city's reconstruction, with 1.6 million square meters of housing erected in the traditional city center, as well as low-rise structures in the Primorskii Prospekt, Avtovo, Bol'shaia and Malaia Okhta, Shchemilovka, and Prospekt Stachek districts (see Map 10).[3] Gas heat was introduced on a large scale for the first time, and water and sewage systems were upgraded.[4] Two large victory parks were opened on Stalinskii Prospekt (the 250-acre Moscow Victory Park) and on Krestovskii Island (the 470-acre Maritime Victory Park).[5] The 1950 dedication of the 100,000-seat Kirov Stadium on that island marked the culmination of Leningrad's reconstruction period (see Figure 14).[6]

The placement of the massive Kirov Stadium along the Gulf of Finland reflected a new set of spatial priorities enunciated for the first time in a new 1947 general plan developed by a team of architects led

by Nikolai Baranov. The 1947 plan carried forward the city's development beyond the original postwar reconstruction period. Its overall conception for future development in Leningrad had several components that would dominate local city planning efforts for decades. In it, for example, Baranov set forth his pet notion that Leningrad should, at long last, become the true maritime city Peter I had initially envisioned.[7] He would later claim that the original idea for the city's "face to the sea" dated from the work of eighteenth-century architect Adreian Zakharov.[8] The 1947 general plan also anticipated new transportation facilities, with a major airport south of the city near the eventual site of today's Pulkovo airport.[9]

Despite these very real achievements, however, the final document—as with all Soviet general city plans of the period—largely ignored major social and economic trends then shaping the city's destiny. These forces rendered Chief Architect Baranov's plans fanciful and obsolete almost as soon as they left his drawing board. To fully appreciate how this was the case, it is necessary to review the entire postwar period down to the 1980s—a period of sweeping social and economic change in Leningrad.

Social Change

To begin with, a major social and demographic transformation was afoot. By September 1945, Leningrad's wartime population had doubled with the arrival of rural in-migrants (coming from such regions as Iaroslavl', Kalinin, Saratov, and Sverdlovsk oblasts) and demobilized soldiers (see Map 1).[10] In other words, a large number, perhaps even a majority, of the city's residents had not lived in the city before the outbreak of hostilities, had only limited personal or familial ties to the city, and, as a rule, had fewer work skills at the beginning of this migratory process than did the city's prior inhabitants.[11] It would take another decade and a half before prewar population levels would be achieved, but, by as early as 1945, Leningrad was becoming primarily a city of migrants. Such disproportionate reliance on migration as a source for new population magnified the demographic chasm created by the horrific civilian losses of the blockade.[12] Among the most visible manifestations of this intense social change have been the "feminization" and aging of the city's inhabitants throughout the postwar period.[13]

Fortunately for local economic and civil leaders, Leningrad continued to attract significant numbers of migrants well into the 1980s, with net annual increases through the 1960s and 1970s running mostly in the 20,000 to 40,000 range, so that the city's population has continued

Map 10.

Major postwar construction projects.

Figure 14.

Kirov Stadium.

to grow at a rather robust pace.[14] This ability to attract migrants reflects in large measure a general transfer of population from the Soviet countryside to urban centers. Nationally, each year from 1951 to 1974, an average of 1.7 million people moved from country to city.[15] Until very recently, this national pattern was magnified in the Northwest Economic Region around Leningrad (see Map 1), where demographer Grigorii Vechkanov had found that 70 of 100 school-age residents in selected rural districts left home to pursue educational opportunities in towns and cities.[16] This large-scale out-migration from nearby rural areas may finally have come to an end during the 1980s, although more data are necessary to verify a trend.[17]

National or even regional trends do not suffice to explain the city's continued attractiveness to migrants. The city's migrant profile demonstrates several rather singular characteristics. In the late 1970s, for instance, much of the city's in-migration consisted of young people attracted by Leningrad's numerous and, by reputation, high-quality educational establishments.[18] By decade's end, over a quarter-million students from all over the USSR were enrolled in the city's institutions of higher learning.[19] The possibility that many students manage to stay in the city after graduation is suggested by available data on the skills and educational levels of the population. These data indicate that the number of specialists in Leningrad with higher or specialized secondary education doubled between 1965 and 1980 alone.[20] Moreover, the city's

general level of educational achievement remained well above the national norm down through at least the 1970s.[21]

The Leningrad population's steady improvement in educational attainment may help compensate for the growing proportion who receive some form of pension or social insurance payment (nearly 25 percent, or 1,064,000 people, on January 1, 1982).[22] The city's elderly may form the core of a potential poverty problem since, nationally, a high correlation may be found between the number of pensioners and the number of residents below the official poverty level, which, during the mid-1970s, was set at a monthly per capita income of about 50 rubles.[23] The strain imposed by the large number of older dependents relative to the working population of Leningrad is apparent even in the limited summary data available on Soviet city budgets. In 1975, 0.8 percent of the average Soviet city budget went to social security payments,[24] whereas in Leningrad nearly 5 percent of the city budget was consumed by such obligations around that time.[25]

Another distinctive characteristic of Leningrad's migrant population has been that it now hails from nearly every economic region of the USSR.[26] Recent migratory data demonstrate that Moscow and Leningrad now stand alone among Soviet metropolitan centers in their sustained ability to attract new population from every corner of the Soviet Union. As the national capital, Moscow remains the single most important political, economic, educational, and cultural center for the country as a whole. In the case of Leningrad, the continued drawing power of the city's educational institutions undoubtedly explains the pattern to a considerable degree. In addition, major construction projects, such as the massive Gulf of Finland dam and flood control project, attract skilled labor from across the USSR.[27]

Ethnic Diversity

Whatever the motivation for moving to Leningrad, such continued migration has not substantially altered the Russians' overwhelming dominance of the town. Leningrad is a city where over 150,000 persons have the characteristically Russian last name Ivanov, over 300 are named Maria Krasovskaia, and over 200 are named Sergei Bobrov.[28] The city's urban diversity peaked as long ago as the time of the 1897 census, when there were over 60 ethnic groups represented in the city.[29] Still, migration throughout the postwar period has brought relatively large increases not only in the city's Russian population, but also especially in the Ukrainian, Belorussian, and Tatar populations (see Tables 2 and 3 and Map 1).

Large-scale Ukrainian and Belorussian migration to the city began over a century ago.[30] The emancipation of the serfs in 1861, combined

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

with the country's burgeoning industrialization, encouraged peasants of both nationalities to move to the city. Between the 1869 and 1897 censuses, for example, St. Petersburg experienced a sharp decline in the absolute and relative numbers of migrants from the gentry of these and all other nationalities, and a concomitant increase in the absolute

and relative numbers of peasant-migrants.[31] This trend was particularly pronounced among the Ukrainians and Belorussians.

Ukrainian migration to the city was relatively low throughout the late nineteenth century, in part because of the relative well-being of the Ukrainian countryside and in part because of the existence of alternative magnets—industrializing centers in the Ukraine such as the Donbas region.[32] During the twentieth century, and especially in more recent years, Leningrad's Ukrainian population began to grow more rapidly, so that by 1979 it had come to constitute the third largest ethnic group in the city behind the Russian and Jewish populations (see Table 3).

Belorussian migration to St. Petersburg/Leningrad has remained high ever since the emancipation of the serfs.[33] This pattern is a consequence of the relatively poor rural living standards in Belorussia, as well as the region's geographic proximity to the city. Prior to the Bolshevik Revolution, Roman Catholic peasant migrants from the Belorussian countryside were drawn to Polish cities, while their Orthodox brethren moved to St. Petersburg.[34]

Recent ethnographic research helps elucidate the underlying motivations for the continuing Tatar migration evident in Tables 2 and 3.[35] Tatars first arrived in the city during the late eighteenth century and, by the middle of the nineteenth, had become prominent in trade. The city continued to attract significant numbers of Tatar migrants throughout the Soviet period until the 1980s.[36] Today's Leningrad Tatars retain a strong ethnic identity across generational and educational barriers, as evidenced in widespread fluency in their native language and observance of traditional holidays. More than half migrated from rural areas, about a quarter from multiethnic cities, and the remainder from small towns scattered throughout the Tatar ASSR along the Volga River (see Map 1).[37]

The conspicuous decline over time in the local Jewish and Polish populations reverses historic trends and can be attributed in large part to the idiosyncratic status of both national groups in the contemporary Soviet scene. Their status reflects both national and international influences rather than purely local ethnic impulses and tendencies. For example, Jewish migration during the nineteenth century was adversely affected by laws and regulations governing Jewish settlement. Consequently, the largest migration of Jews to the city came during the early Soviet period, when such restrictions were removed.[38] The decline of the city's Jewish population more recently reflects local discriminatory practices that have prompted many Jews to leave Leningrad for Moscow, Israel, or the United States. A different pattern holds for the Poles, many of whom chose to return to their homeland following the establishment of an independent Poland at the close of World War I.[39]

Economic Change

The sweeping social changes just chronicled have been reflected in and are a consequence of significant economic transformations that have been taking place in Leningrad since the lifting of the blockade in 1944. To appreciate the extent of these trends, it is important to recall that St. Petersburg long served as an industrial center of considerable significance. Despite several distinct disadvantages—the city's location on the outer edges of Russia and Europe, its adverse climate, its lack of ready access to natural resources and to markets, and so on—in its early days the capital soon developed a small, primarily state-supported industrial base oriented toward the needs of the local economy and those of the emperor's army and navy.

By the late nineteenth century, the city had emerged as the focal point of one of the more powerful industrial regions in Europe. Until the Bolshevik Revolution, however, the city's industrial base continued its dependency on foreign and state capital markets, as well as on imported raw materials and finished manufactured goods brought in through its expanding port. As Steven Smith has suggested, by the outbreak of World War I, the city had come to represent a unique island of technologically sophisticated state-supported industrial production.[40] Unlike the more diversified industrial base in Moscow, St. Petersburg's industry remained heavily concentrated on such state-dependent large-scale industries as metalworking and chemical production.[41] Consequently, the city never came to hold overall sway in the Russian national market the way Moscow would.

St. Petersburg ultimately failed to retain national economic preeminence for numerous complicated reasons beyond the scope of this particular study. Certainly, the transfer of political power from the city in 1918 guaranteed Moscow's dominant position for the remainder of this century. However, other factors contributed to Moscow's relative economic power, even before the Bolsheviks moved their government. For example, by the late years of the nineteenth century it had already become apparent that St. Petersburg would not develop into an "import-replacing" city.[42] This failure was expressed in the city's historic and continuing inability to create an exuberant and productive city-region. Such areas manifest intense and diverse rural, industrial, and commercial activity tied together by the import-replacing city's overwhelming economic energy.[43] This all-encompassing dynamism can exist only when a city replaces its imports with internally produced products—a feat never accomplished on a sufficiently large scale to secure St. Petersburg/Leningrad's economic power over Moscow.

Initially, St. Petersburg's continued dependence on imported goods helped the capital emerge as a major transportation center, de-

spite its peripheral location. By 1851, Russia's first major railroad connected the capital's port to Moscow, and the next year, 38 percent (by value) of all Russian foreign trade passed through St. Petersburg (representing five times the value of foreign goods passing through the second largest port—Riga).[44] This preeminence was challenged as early as the century's end, once new rail lines linked Moscow and Odessa, Moscow and Riga, and eventually Moscow and Warsaw (and through Warsaw, directly with the heart of Europe). These developments emphasized St. Petersburg's numerous geographic limitations.[45]

Over the years of Soviet rule, Leningrad political elites and economic and urban planners have developed four distinct strategies to overcome economic and geographic liabilities:

1. Political laissez-faire . Reliance on political patronage ties to secure economic resources within the context of a decentralized, mixed state-private economy (1917–1926).

2. Skilled diversification . Reliance on a skilled labor force, an extensive heavy and defense-related industrial base, and a major light-industrial capacity to fuel economic expansion (1926–1945).

3. Consumer-oriented internationalism . Reliance on expanded consumer goods production, extensive trade with the West, and a disproportionate claim to postwar reconstruction funds to lead economic recovery (1945–1948).

4. Skilled specialization . Reliance on a skilled labor force, an increasingly specialized heavy and defense-related industrial base, and, especially since 1951, a leading scientific infrastructure combined with a reduction in light industrial capacity to sustain economic growth (1951–present).

The fourth and most recent strategy—skilled specialization—has significantly altered the contour of the city's economy to the point where a new Leningrad economic structure may be said to have emerged over approximately the past three to four decades. The focus of this study is principally on this new Leningrad as a special case of Soviet regional management. Before discussing the fourth strategy in greater detail, however, we should briefly review its predecessors.

The initial response (1917–1926) to the city's precipitous decline during the Civil War was largely political. The city's Communist Party organization remained subjugated to the whim of Comintern Chairman Grigorii Zinov'ev. Zinov'ev, who succeeded Leon Trotsky as Petrograd city soviet chairman in 1917, attempted to use his Petrograd post and power base to challenge Joseph Stalin for party leadership during the mid-1920s.[46] By 1926 Zinov'ev had lost that quest, as Stalin had members of Zinov'ev's "Left" opposition expelled from major party posi-

tions. Control over the Leningrad party organization quickly passed to a new regional party first secretary, Sergei Kirov.

Before being removed from his Leningrad posts, Zinov'ev had paid far greater attention to the care and maintenance of a loyal political machine than to the city's economic recovery. In short, his strategy, as well as that of his planners and managers, appears to have been simply not to develop a coherent response to the threat of permanent economic decline. Although Petrograd/Leningrad slowly managed to regain its population and economic base throughout the early and mid-1920s, the lack of a sustained program of economic development severely limited the scope and durability of that recovery.

Both Kirov and, following his assassination on December 1, 1934, Andrei Zhdanov, his successor as regional party first secretary, tried to build on their city's historic economic strengths (a skilled labor force, an extensive heavy and defense-related industrial base, and a major light-industrial capacity). This second Leningrad development strategy of the Soviet period (1926–1945), which conformed closely to that of the national five-year plans, catapulted the local economy into preeminence in numerous areas of highly sophisticated industrial production. By the eve of World War II, the city had reemerged as the Soviet Union's leading center for industrial innovation.[47]

The third approach to economic development proclaimed by the city's postwar leadership proved short-lived (1945–1948), quickly becoming entangled in some of the most bitter and destructive political struggles of Soviet history.[48] Leningrad elites of the period were outspoken proponents of major policy positions that subsequently failed to gain Stalin's endorsement.[49] For example, as early as June 1945, Aleksei Kuznetsov (who had replaced Zhdanov as Leningrad regional party first secretary earlier that year) argued before a joint session of the Leningrad regional and city party committees that the Communist Party should assume full responsibility for guaranteeing "normal relaxation," now that the war was over.[50] Kuznetsov repeated this theme in an address launching the 1946 Supreme Soviet campaign in Leningrad,[51] as did Zhdanov (who was now a member of the national Central Committee Secretariat in Moscow) in a remarkable address to the residents of Leningrad's Volodarskii Election District during that same campaign.[52]

While other national leaders of the period typically ignored local concerns in their election speeches,[53] Zhdanov relied heavily on his wartime experiences in the city to advocate policies designed to improve the quality of life of Leningrad citizens. The new Leningrad economy, Zhdanov argued, would be based on consumer-goods production, extensive trade with the West, and a disproportionate claim to postwar reconstruction funds. He thus linked Leningrad's resurgence

to particularly volatile leadership struggles in Moscow over the Soviet Union's peacetime relations with wartime allies and, ultimately, to his own fate.

Following Zhdanov's death in August 1948, his major rivals, Georgii Malenkov and Lavrentii Beria, set in motion a large-scale purge of Zhdanov protégés in Leningrad and elsewhere. Numerous Leningraders holding national posts together with nearly all senior city and regional officials were removed from their positions, never to be seen again, in what has become known as the Leningrad Affair.[54] Beyond Leningrad, in Gorky (previously Nizhnii Novgorod), where Zhdanov had served prior to his arrival in Leningrad, numbers of leading Communists also fell victim to the "provocative Leningrad Affair, fabricated by Malenkov."[55]

The conventional explanation of the affair interprets the events of 1948 and 1949 as a consequence of Zhdanov's protracted struggle for power with Malenkov. Robert Conquest, for example, observes that the one uncontestable outcome was for Zhdanov's men to be replaced by Malenkov's.[56] The few Soviet accounts of the Leningrad purges that have thus far come to light—including Mikhail Gorbachev's mention of these events in his address commemorating the seventieth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution—are not strikingly different from that offered by Conquest.[57]

Recently, Western analysts have identified policy issues within the personal struggles of the period. Werner Hahn identifies multiple and linked areas of policy concern that might underlie the purges of 1948 and 1949: the nature of Soviet relations with the West, the possibility of reorientation of the postwar Soviet economy toward consumer industries, and the distribution of a majority of reconstruction funds to "front-line" regions such as Leningrad (as opposed to "home-front" areas to the east).[58] The precise role that any one of these issues played in the Leningrad Affair is likely to remain uncertain. Nevertheless, one should note that Leningraders' ultimately unsuccessful plans for a postwar reorientation of their region's economy were tied to improved relations with the West, a reorientation of the economy toward consumer-goods production, and a disproportionate claim to postwar reconstruction funds. In this respect, Leningrad's resurgence became inexorably linked to Moscow's leadership struggles in a particularly explosive fusion of local and national politics. This blend ultimately proved the undoing not only of several senior Leningrad political officials and scores of their protégés, but also of their strategy of economic revitalization through the expansion of consumer industries and international trade.

Following the extensive purges of Zhdanov associates during 1948 and 1949, local leaders, together with their partners and sponsors in Moscow, returned to the basic strategy of the 1930s, but with several

important variations. In many ways, this fourth approach (1951–present) was merely a modification of the growth strategy of the prewar five-year-plan periods, relying on heavy-industrial production and technological innovation. Nonetheless, the current strategy varied from its predecessors in being predicated on economic specialization rather than diversification. Moreover, since the Fifth Five-Year Plan (1951–1955), the strategies have relied more explicitly on the interaction of science and industry than in the past. This fourth approach to Leningrad's economic development—the focus of the policy studies to follow—remained in force from the 1950s through the 1970s and was incorporated into the Leningrad general plan for 1986–2005.[59]

Its durability suggests that we must assume this latest approach to economic development has in fact come to represent an accepted official view of Leningrad's role in the national Soviet economy. Although it would be misleading to identify this most recent Leningrad growth strategy with any single official, we can turn to the pronouncements of two Leningrad regional party first secretaries—Frol Kozlov, who held the post from 1953 until 1957, and Grigorii Romanov, the incumbent from 1970 until 1983—for comprehensive recitations of this latest strategy for the city's economic development. While this rhetorical device allows us to examine the period under consideration by focusing on two end points, it should in no way be taken to mean that Kozlov and Romanov monopolized leadership during the past three and a half decades. Regional party first secretaries Ivan Spiridonov (1957–1962), Vasili Tolstikov (1962–1970), Lev Zaikov (1983–1985), and Iurii Solov'ev (1985–1989), as well as scores of other local and national political leaders, have also played critically important roles in developing this present-day regional economic strategy.

Kozlov's Development Strategy

Throughout the 1950s, Frol' Kozlov, initially as city party first secretary, then as regional party second and first secretary, and later as first deputy prime minister of the USSR, vigorously advocated the reorientation of the Leningrad economy around technologically specialized industrial production. This orientation conformed with his views on the national economy; in fact, some Western analysts see Kozlov as having led coalitions opposing Khrushchev's plans to shift national resources from industry to agriculture and light-industrial production.[60] In addition to an emphasis on heavy-industrial production, Kozlov argued that, given Leningrad's extensive scientific research community and its famous industrial plant, the city could come to serve very specific functions within the overall Soviet economy: those of innovator, producer of high-quality industrial goods, and leader in

precision-instrument making.[61] To Kozlov's mind, such a growth strategy would necessitate a phasing out of the city's light-industrial capacity—a goal quite at variance with the strategy of industrial diversity followed by previous Leningrad leaders.

Jumping ahead to the period of Grigorii Romanov's tenure as regional party first secretary, we find remarkably few changes in the rhetoric of Leningrad economic development.[62] More importantly, that strategy had come to fruition (in large part because of the specific policies examined later in this volume). The realization of this growth strategy, as seen in the growing dominance of machine and metal industries, and the accompanying decline in chemicals and petrochemicals, forestry, construction material, food processing, and other light industries, is a direct consequence of industrial investment policies.[63] The achievement of this pattern must be considered all the more striking when compared to trends in the Moscow and national Soviet economies and when taking into account the demographic trends described earlier, most of which inhibit the expansion of the workforce available for service in heavy industry (see Table 4).

Meanwhile, the role of science and related services in the Leningrad economy has expanded. By the 1970s, scientific and related institutions represented the city's second largest employer, behind industry.[64] The city's scientific research establishments and institutions of higher learning employed almost one fifth of the Leningrad work-force, and the city was second only to Moscow in the number of scientific workers employed in the local economy.[65] In 1982, one in 11 Soviet scientists worked in Leningrad, and a much higher share of the country's skilled specialists were to be found there.[66]

The close interaction between the city's enormous scientific community and its powerful industrial base is apparent in an emphasis on applied rather than basic research—an emphasis reflected in the distribution of Leningrad scientific workers by discipline during the 1970s.[67] Leningrad party leaders are quick to point out that the mission of the newly constituted Leningrad Scientific Center of the USSR Academy of Sciences, which was established in March 1983 by bringing together under a single institutional umbrella preexisting academy research institutes, was to improve the coordination of basic and fundamental research on the one hand and industrial activity on the other.[68]

The increasingly close coordination of Leningrad's scientific and industrial organizations pushed the city ahead of all other Soviet industrial centers in various measures of technological innovation. According to Leonid Bliakhman of Leningrad's Institute of Socioeconomic Problems, during the mid-1970s the city led the Soviet Union on a per capita basis in the annual economic impact of the introduction of new technologies into production, the number of new types of machines

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

generated annually, and the number of newly automated production lines.[69] By the early 1980s, 9 percent of all new Soviet production technologies were being developed in Leningrad.[70] These innovations may help explain how Leningrad plants produced 10 percent of all export machinery, 52 percent of all turbines, 52 percent of all generators and 26 percent of all printing facilities, even though the city's economy constitutes but 3 percent of the Soviet Union's total national industrial capacity.[71]

The implementation of this economic development strategy contributed to the transformation of the city's industrial profile and the emergence of linkages and cooperation among local industrial and scientific organizations. In the short term, this strategy has been a success, as the city has achieved respectable rates of economic growth.[72] We should note further that such growth has occurred in part because Leningrad's dominant economic sectors (machine construction, shipbuilding, and other heavy industries) are precisely the sectors that have expanded the most throughout the Soviet Union during the past 30 years.[73] In this sense, then, the strategy may represent nothing more than the effective local implementation of national priorities. Whichever came first, the Leningrad approach or the national goals, it is clear that Leningrad benefited from central investment and growth patterns.

Spatial Consequences

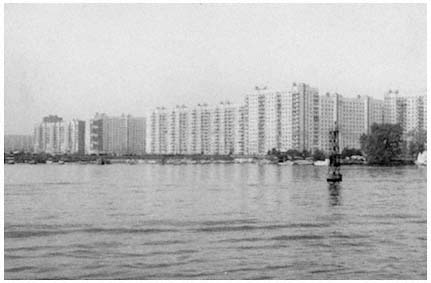

These sweeping social and economic changes of the postwar period proved to have significant consequences for the physical organization of the city and its metropolitan region long before the 1947 general plan could be revised. For example, the city's sustained ability to attract migrants, noted earlier, combined with a massive housing construction effort to meet the needs of those migrants to produce extensive urban sprawl. In 1951, an average of 3.3 families lived in each Leningrad apartment.[74] Beginning in the mid-1950s, Leningrad construction trusts, in accord with Khrushchev's housing program, began expanding the city's housing stock at an ever-accelerating rate.[75] During most of the 1970s, for example, the average per capita living space available in Leningrad grew at a rate exceeding that of other major Soviet urban centers.[76] Despite a slowdown later in the decade, it is obvious that the city has begun to approach the national average of 80 percent of all families living in their own apartments (see Figures 15 and 16).[77] At the end of 1979, for instance, a Leningrad family of four would occupy, on the average, 684.4 square feet of living space—the size of a moderate one-bedroom apartment in New York. While many North Americans or West Europeans would probably consider this inade-

Figure 15.

Apartment buildings along Nevskii Prospekt.

Figure 16.

Apartment buildings seen from the Moika River Canal

with the Pevchevskii Bridge in the foreground.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

quate, it represents an enormous improvement over the dreadful housing conditions of 1951.

Such achievements have not come without cost to the urban environment. In search of land for their gargantuan housing projects, local planners quickly turned to vacant sites beyond the city's boundaries. As the years have passed, successive layers of housing superblocks have built up, much as polyps build their coral reefs (see Table 5; Maps 8 and 10; and Figures 17–19). The city of Leningrad swelled from 323.4 square kilometers in 1957 to 570 in 1974.[78] This prodigious spatial growth transformed what had remained for many inhabitants a cozy nineteenth-century walking city of just 105.4 square kilometers in 1917 into a massive metropolitan agglomeration extending over 1,359 square kilometers in all by 1980.[79]

Unlike much of the urban sprawl in the West, local planners have relied extensively on subway-based mass transportation, rather than on the private automobile. This growth strategy inhibited the emergence of an efficient and flexible regionwide service, commercial, and cultural infrastructure. Except for Moscow and the largest cities of the People's Republic of China, no other urban center of comparable size has experienced such immense territorial expansion without reliance on the private automobile. If the historic central city could be traversed on foot, the new Leningrad of the late twentieth century must be crossed by wearisome bus, streetcar, and subway rides (see Figures 20 and 21).

Figure 17.

View of housing superblock on Vasil'evskii Island.

Figure 18.

Minidistrict.

Figure 19.

Small Avenue on Vasil'evskii Island. Examples of the old and new styles.

Figure 20.

Pedestrians in front of the old Singer building, now the House of Books.

Figure 21.

Streetcar on Middle Avenue on Vasil'evskii Island.

And traversed it must be, for housing and population have both moved outward (see Table 6). Fleeing decrepit communal apartments downtown, both residents and recent arrivals from the countryside have filled the massive new districts ringing the former city center. As a result, the city's center increasingly is becoming a home to students and pensioners—two groups requiring less personal space—while the typical Soviet family of three (parents and a single child) are relocating further and further out (see Table 7). This trend has placed considerable pressure on the service infrastructure of Leningrad's new districts.

Industrialized Construction and Superblocks

Once one moves beyond the city's historic center into these massive new neighborhoods, Leningrad becomes a far less special—and more typically "Soviet"—city. Quite early on, postwar municipal leaders created several new institutions to streamline and improve the planning and the design of these new districts, in accord with Baranov's 1947 general plan.[80] They also sought to speed up the construction cycle. In 1955, for example, the Main Leningrad Construction Administration (Glavleningradstroi) commenced operations, with the Main Leningrad Construction Materials Administration (Glavlenstroimaterialy) following suit a year later.[81] These bodies are the Leningrad offices of the State Committee on Construction and the State Committee

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

on Construction Materials, two agencies of the USSR and the 15 union republic councils of ministers charged with responsibility for directing the construction industry throughout the nation. In Leningrad, the trusts operate within departments and main administrations of the Leningrad city soviet. They are among the largest administrative agencies of the city soviet, with the Main Leningrad Construction Administration, for example, operating nearly two dozen smaller construction

Figure 22.

Example of the new minidistrict.

firms. One such firm, the first Housing Construction Combinant (DSK no. 1) opened for business during the 1950s.[82] In short, Glavleningradstroi and Glavlenstroimaterialy are the Leningrad construction industry.

Leningrad quickly emerged as a pioneer in large-scale industrialized construction methods. The Soviet Union launched the world's most ambitious housing construction program after a July 1957 party and state decree on the further development of housing construction.[83] This effort relied on the introduction of assembly-line production of prefabricated building units. This so-called block-section construction technique, now used throughout the Soviet Union, was largely developed and perfected in Leningrad during the late 1950s and early 1960s.[84]

Widespread utilization of the block-section method produced a network of instant neighborhoods as enormous housing projects sprang up in a matter of months. These superblocks or minidistricts (mikroraion ) became inexorably linked to the introduction of new construction technology.[85] The minidistrict—a planning rather than a political unit—can be traced to the European modernist tradition (see Figure 22). It represents an effort by the architects and planners involved to create safe and attractive residential districts by removing all basic neighborhood functions from the street, streets being viewed as dangerous, chaotic, and generally inhospitable environments. Urban designers therefore anticipated that developing social amenities in self-

contained communities would make such services more convenient and accessible to larger numbers of citizens.[86] In the Soviet Union the concept evolved considerably, so that a complex doctrine concerning the minidistrict had emerged by the 1970s.[87]

Leningrad architects now generally view the minidistrict as an extension of the Petersburg tradition of grand ensembles. Few casual observers can distinguish Leningrad's standard new minidistricts from those found in Moscow and in such typical provincial cities as Sverdlovsk in the Urals and Vladivostok on the Pacific coast. A handful of experimental minidistricts that are spread throughout the city's new developments undeniably benefit from greater concern for aesthetics than do the typical residential districts in other Soviet communities.[88] Nonetheless, the emergence of industrialized construction techniques, the commitment to mass-scale housing, and the rigid control of construction agencies have generally produced mile upon mile of low-grade and unimaginative structures, both in Leningrad and elsewhere in the Soviet Union.

The 1966 General Plan

By the early 1960s many municipal officers saw that Baranov's 1947 plan had outgrown its usefulness. A new and more comprehensive plan was now needed for the effective management of the city's continuing development and growth, especially in the new minidistricts being built by a technology that did not exist when Baranov's plan took effect.[89] Moreover, the Soviet architectural community was slowly emerging from its Stalinist isolation. In 1958 the World Congress of Architects met in Moscow, and in 1960 the All-Union Conference on City Planning convened the first gathering of its kind in years.[90] These meetings mark the initiation of the post-Stalinist thaw in architecture and planning, a thaw that came just as work began on a new 25-year general plan for Leningrad's development that was to take effect in 1966.[91]

In 1966 the USSR Supreme Soviet enacted the General Plan of Development of Leningrad and the Leningrad Suburban Zone, in accordance with a draft prepared over a seven-year period by Leningrad city planning agencies—especially the Main Architectural Planning Administration—and endorsed by the Leningrad city and regional soviets and party committees.[92] The city soviet's Main Architectural Planning Administration was established to formulate not only the general plan for the city, but also various thematic and district plans that elaborate future construction in the city for up to 30 years. A parallel institution to Glavleningradstoi, the city soviet agency responsible for construction activities, the Main Planning Administration submits draft

plans for review and approval by the city soviet. At various points in Leningrad history, there has also been an office of the chief architect subordinate to the Main Architectural Planning Administration. At present, the position of chief architect is distinct from the main administration, reporting in parallel fashion directly to the city soviet's executive committee. While the chief architect is responsible for the city's architectural integrity, the Main Architectural Planning Administration has assumed full authority over the preparation of the increasingly multipurpose general plan.

Once approved at the city level, a draft general plan must then be approved by the Leningrad regional soviet and passed as a state law by the USSR Supreme Soviet. As will become apparent in our discussion of the 1986 general plan, changes may be introduced at any stage prior to the plan's enactment as law. This review process is complicated by party oversight at every stage. Although party agencies do not have formal legislative authority, no draft general plan will be ratified by a soviet until the parallel party committee has approved it. Each review prolongs the planning process—helping to explain why it took seven years to prepare the 1966 general plan. None of these reviews are public, however, as the actual plan document is classified as secret for reasons of national security.

Once completed, the 1966 plan provided a general urban orientation to coordinate and provide direction for future regional components of national economic and technical plans—the five-year plans—during the next quarter century. Put forward and implemented under the direction of the city's chief architect, Valentin Kamenskii, the document drew explicitly on the city's planning and architectural traditions.[93] The existing historic city center was as much of a model for this new projection of Leningrad's future as were central decrees emanating from Moscow.

Seeking to create a more salubrious urban environment, the creators of the 1966 general plan shifted the focus of construction toward the Gulf of Finland. Thus, the low-lying areas near the coastline were to become the city's focal point. As noted earlier, this "movement to the sea" had first been proposed in the 1940s by Nikolai Baranov. It required the elevation of the low-lying areas by extensive landfill and flood control projects, as well as the construction of massive housing projects on reclaimed land at the western tip of Vasil'evskii Island and in the southwest.[94] The plan also provided for the development of major recreational facilities to the northwest along the Gulf of Finland. Such movement to the north and west became acceptable from a strategic point of view once the international boundary with Finland had been shifted from 22 miles away from the city to over 100 miles distant as a consequence of the Soviet victories in the 1939–1940 Winter War and World War II. More detailed plans for the city's 16 districts were

developed to further refine general planning objectives (see Map 11).

The 1966 plan enumerated eight primary objectives that deserve special attention:[95]

1. Limitation of population and territorial expansion

2. Movement to the sea

3. Creation of new districts

4. Historic preservation

5. Improvement of intraurban transportation and communications

6. Development of the city's scientific traditions

7. Improvement of transportation approaches to the city

8. Satellite cities, greenbelts, and regional planning

Limitation of Population and Territorial Expansion

The chief goals of all Leningrad plans throughout the Soviet period have included the limitation of population growth, reduction of population densities, and minimization of built-up territories.[96] Despite repeated failures on each of these fronts, the 1966 general plan continued to restate population targets that had already been overtaken or would soon be. Under the provisions of the plan, municipal officials were to limit the city's population to 3.5 million residents by 1990. Gosplan, the State Planning Committee in Moscow, also projected a ceiling of some 4 million persons tied in one way or another to the city's economy. By 1970, these figures were already surpassed.[97]

During preliminary discussions of the plan, as early as 1960, Valentin Kamenskii had identified the need to limit urban sprawl by concentrating territorial development in a few areas.[98] Provisions to implement Kamenskii's proposals found their way into the 1966 general plan. Accordingly, city officials were to contain the area of urban development within 200 square miles, of which 185 were to be in use by 1990 (as opposed to 107 square miles in 1966).[99] Moreover, the city's population was to be distributed more evenly throughout Leningrad, with inner-city districts losing population to outlying regions. To a considerable degree, this last plan projection has been fulfilled.

Movement to the Sea

By the mid-1960s, Aleksandr Naumov had endorsed various proposals to redirect Leningrad's development in the direction of the Gulf of Finland.[100] Nikolai Baranov supported Naumov's efforts, characterizing this attempt "to reorient the city and to turn it into a real maritime city" as one of the most successful elements of the new general plan.[101] In its final form, the 1966 plan provided for the widespread develop-

Map 11.

Districts (raiony) of the city of Leningrad.

ment of the regional shoreline—especially of the gulf's north shore—for recreational use.[102] This vision was based on extensive analysis of the region's geological conditions:[103]

1. The shoreline areas would have to be elevated, with bogs and swamps being drained in the northwest and southwest.

2. The best site for a new airport was to the city's south, a location that would limit population expansion in that direction.

3. The best lands for agricultural production were to the north, northeast, and southeast.

4. Urban development would have to be limited to landfill areas in previously undeveloped lands of the Neva floodplain.

On the basis of such surveys, the planners suggested that a combination of landfill and flood control—including the construction of the aforementioned dam across the gulf from Lomonosov through Kronstadt to Gorskaia—could prevent major flooding (see Map 12).[104] Accordingly, specific construction plans were developed for high-density experimental housing districts on the west end of Vasil'evskii and Dekabristov islands and along the Neva to Rybatskoe and the gulf north to Ol'gino.[105]

Creation of New Districts

Increasing population, combined with a policy of reduced population densities, created pressures for the rapid development of new housing stock in outlying areas. The 1966 general plan projected the construction of scores of new minidistricts with up-to-date cultural, economic, and educational amenities. Forty-five percent of all new housing was charted for areas north of the city, and 50 percent to the south, with the remaining 5 percent to be built in the existing city (primarily on Vasil'evskii and Dekabristov islands).[106] These apartment buildings were to be constructed in accordance with the most recent industrialized techniques in districts located in a circle around the historic city center. During the plan's first eight years 393,000 apartment units were completed and made available to 1.25 million residents.[107] But, as will be discussed later, local architects have criticized such massive construction efforts as lacking aesthetic standards.

Historic Preservation

The 1966 general plan emphasized preservation of the traditional city center as the focal point of Leningrad life. It acknowledged the need to preserve and to cultivate a townscape formed by "generations of Russian artists" into "one of the most beautiful cities in the world."[108] Historical preservation efforts were to extend to "Lenin

Map 12.

Projected recreational zone and greenbelt in the 1966

general plan, showing the Gulf of Finland dam.

Places," a decision that brought large swaths of the nineteenth-century cityscape under protective measures.[109] The plan also provided for major restoration efforts at satellite palaces and parks in Pushkin, Pavlovsk, Petrodvorets, Lomonosov, and Gatchina.[110] Such concerns would become more pronounced as time passed, with entire proletarian districts from the end of the late nineteenth century coming under preservation scrutiny by the late 1980s.[111]

Improvement of Intraurban Transportation and Communications

The combined emphasis on constructing new districts and maintaining the historic city center necessitated an extensive transportation improvement program. Indeed, transportation problems have emerged as perhaps the most troublesome feature of contemporary Leningrad. Residents have moved away from the central city, but major employment sites, commercial and city services, and tourist attractions are still concentrated in the historic central core. By the early 1980s, one quarter of the pedestrians along the city's main commercial axis—Nevskii Prospekt—were visitors from out of town.[112] Moreover, approximately half of the population of the city's surrounding suburbs worked in the city center.[113] All these nonresidents of the city must rely on public transportation to move about Leningrad's major urbanized areas.

From 1950 until the early 1970s, the number of passengers using the city's public transportation system doubled, the duration of an average trip increasing to approximately 30 minutes.[114] Much of this expansion occurred after the city's subway system opened in 1955, which had a substantial impact on transportation ridership patterns throughout the Leningrad region.[115]

The 1966 general plan provided for an increase in subway and private auto use and projected declining ridership on other transportation systems.[116] Consequently, the plan recommended extensive subway and highway construction programs, as well as development of improved services for the burgeoning Soviet automobile ownership. Despite these efforts, however, highways and auto service facilities have not kept pace with auto ownership.

Development of the City's Scientific Tradition

Although Leningrad's position declined after the transfer of the headquarters of the Academy of Sciences to Moscow in 1934, the city is still a vital scientific center. The 1966 general plan called for further exploitation of such scientific resources.[117] The importance of the local scientific community for Leningrad's economic development will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Improvement of Transportation Approaches to the City

The 1966 general plan proposed the construction of new port and airport terminals, as well as the rationalization of rail routes within the city limits.[118] Within a few years these new facilities began to be put into operation. The Moskovskii Station complex was expanded and modernized and plans are under way to phase out the operation of the Varshavskii Station, shifting all passenger traffic to the Baltiiskii Station less than a kilometer away. This consolidation of rail service constitutes a critical development for a city where more than 50 times as many people arrive by rail as by air.[119] Subsequent to the 1966 general plan, a new airport opened south of the city at Pulkovo, and a new passenger port for cruise ships was established at the western end of Vasil'evskii Island.[120]

Satellite Cities, Greenbelts, and Regional Planning

Leningrad planners began to emphasize the need for regional planning approaches during the late 1950s.[121] The plan ratified in 1966 incorporated this regional vision as it sought to govern land-use decisions for some 14,000 square kilometers beyond the city's traditional boundaries, including a 2,590-square-kilometer outer greenbelt free from all development and a 518-square-kilometer inner belt with only limited and strictly controlled use.[122] The plan also urged the full development of satellite centers at Kolpino, Pushkin, Pavlovsk, Gatchina, Petrodvorets, Lomonosov, Sestroretsk, Zelenogorsk, and Petrokrepost'-Kirovsk (see Map 2).[123]

This expansion of city planning to encompass the entire metropolitan area represented a significant innovation in Soviet planning efforts. It was permitted in part by the dominant role in Leningrad of planning agencies of regional-level party institutions that traditionally have sought to integrate the entire region (oblast) under their direct control. This pattern stands in sharp contrast to the situation in Moscow, for example, where city and region remain distinct political and administrative entities. Consequently, the city of Moscow has annexed more and more territory, never quite keeping pace with metropolitan expansion.

More significant, perhaps, was the Leningraders' strategy of planning for metropolitan expansion before development had occurred, thereby channeling growth into desired patterns. The emphasis on greenbelts and satellite cities reflected an awareness among planners of the need to keep ahead of physical growth.

Although planners were unable to stay ahead of the game—in large part because of their striking underestimation of the rate of increase in the region's population—the efficacy of their regional vision became

increasingly apparent with the passage of time. By the late 1970s, several leading economic planning specialists were arguing that the entire Leningrad region—an oblast, please recall, only slightly smaller than Indiana—must be considered as part of a fully integrated unit with the city itself.[124] This conception, as we shall see in a moment, came to form the core of the proposals for the 1986–2000 general plan. It now constitutes a major Leningrad contribution to Soviet urban planning practice and philosophy.

As proposals for the regionalization of planning approaches emerged over the course of the 1970s, the regional party committee took the lead in encouraging integrated plans and, by mid-decade, secured the cooperation of republican and national planning agencies.[125] Again, as we shall see, this development has since transformed all economic and physical planning efforts.