Narrative Organization

Brian Henderson

Thelma & Louise has no voice-over narration, makes no use of the frequentive, and has no flashbacks or flash-forwards. Like many, perhaps most, films, it tells its story in chronological order, in what might be described as an unfolding present. What is unlike other films, however, are the ways in which Thelma & Louise organizes narrative time and the distinc-

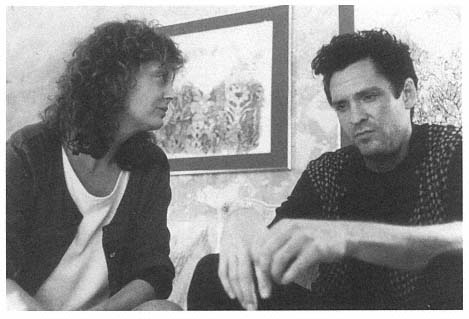

Louise with Jimmy

(Michael Madsen)

tive temporalities, fundamental to all the effects and meanings of the film, that result.

The killing of Harlan turns the lives of Thelma and Louise upside down: suddenly their relation to the past is uncertain; their future unknown. They flee to the open road, "not so much bound to any haven ahead as rushing from all havens astern" (Melville). The film itself fissures at this point, launching a parallel montage between investigating police and escaping women that is sustained until the film's-end face-off at the Grand Canyon.

The time dimensions of the title characters' flight are surprisingly indeterminate—not only the hour and the day of any given scene but also how much time is supposed to have elapsed between any two successive scenes and how long it has been since their journey began. The few clues provided are retrospective. Thelma says well after the fact that it was 4:00am when she first tried to reach Darryl by telephone—where was he? Later she tells the state trooper they hold at gunpoint that she and Louise would never have pulled a stunt like this three days ago—they seem to have been gone much longer than that. The alternation of filmic night and day usually time-orients viewers but this too is undermined, and time stretched out, by the women's driving around the clock;

Ridley Scott (right) on the set of Thelma & Louise

the Oklahoma City episode—Louise in one room with Jimmy; Thelma in another with J.D.—is their single off-road night.[1]

Fiction-film police work is often shown in a pseudo-documentary manner, sometimes even with the date and hour stamped on the beginning of scenes. However, the police scenes in Thelma & Louise are as temporally indeterminate as the women's scenes—we do not know when they take place or how much time elapses between them. How can the film sustain a floating time scheme in each of its two narrative strands? Because the two strands prop each other up: the considerable ellipses within each strand intersperse with those of the other, filling in its gaps and thereby covering for it. Thus the film-makers can break away from Thelma and Louise to the police at any time they wish and come back to them at any later point in their journey they choose. This is a worry-free formal scheme that allows the film-makers to skip what they want to skip and to show what they want to show. A single-stranded Thelma & Louise would have had to account for its ellipses, perhaps by dialogue, by time-passing montages, by dissolves, and/or by other devices: a different film.

What is the point of this scheme? It serves to immerse us radically in Thelma and Louise's divided temporality. The characters exist simultaneously in two temporal modes—a continual motion forward and a continual reflection backwards. "Go!" "Go, Go!" and "Go, Go, Go!" are words we hear frequently in the film, even, when Thelma jumps in the car after robbing a convenience store, "Go! Go! Go, Go, Go!" Each of the women has a paralyzing crisis in the course of the film: Thelma after the killing lies inert on a motel bed, then sits in a daze by the pool; Louise after the theft of the money sits on the floor of another motel room in a stupor. The solution in both cases, effected by the other character, is to get the stalled one back in the car and on the road. It is the road itself, regardless of destination, which is curative.[2]

In the other temporal mode, awareness lags behind events but comes more forcefully for that reason. (Knowledge that follows action is common in Western literature, especially in tragedy.) Louise shoots Harlan, then, addressing his sitting-up corpse, cautions him to change his behavior: "You watch your mouth." By this point, of course, he cannot speak or hear her words—Louise is temporarily denying the knowledge that will change her life. Thelma seems quicker on the uptake; when Darryl offers neither support nor trust, she understands her fate instantly. "When do we get to Mexico?" she says to Louise, in effect signing on for the long drive. Thelma's most profound realizations come later, however, reflecting her character's astonishing growth. Near the end she understands that Louise was raped in Texas some time ago and that this event still shapes her life. Thinking of the rape that she herself barely escaped, thanks to Louise, Thelma ratifies ex post facto the killing of Harlan, wishing only that she had done it herself. She then says, in the film's crowning realization, "My life would have been ruined much worse than it is now."