8—

Concentrating Resources in the Older Cities

Without exception, governments in the region's older cities are strongly committed to using public resources to influence the pattern of development. None has been willing to accept as unalterable the economic and demographic developments of the past three decades. Instead, every city government has sought to check the employment and population trends that have changed the fortunes of the older cities. The steady decline in the cities' share of regional employment has produced a variety of public efforts designed to retain existing jobs and attract new ones. In response to the middle-class exodus from the core, cities have devoted substantial resources to urban renewal, middle-income housing, and related programs. Zoning, urban redevelopment, and other public powers have been used to enhance the attractiveness of the older cities for upper-income households. Substantial efforts also have been made to improve poor neighborhoods through public housing, slum clearance, model cities, code enforcement, and other programs.

Underlying these city efforts to influence development have been strong political pressures. City dwellers expect their governments to do something about the erosion of jobs, inadequate housing, neighborhood decay, and declining public services. Candidates for public office amplify these concerns by holding incumbents responsible for the loss of business firms and middleclass families to the suburbs. And office holders steadfastly assert that their programs will reverse the tide, and restore the city's economic and social health. Thus, Mayor John Lindsay exuded confidence about his administration's ability to "create more jobs and a better economy in New York City," and in so doing "help the poor [and] alleviate the fiscal crisis."[1] His predecessor, Robert Wagner, was certain that city housing programs were "inducing more and more middle-class people to move back from the suburbs into the city."[2] Wagner also sought to make New York the "first city without slums."[3] The fact that neither Lindsay's economic development program nor Wagner's housing efforts had much overall impact on development trends did not dis-

[1] Quoted in Clayton Knowles, "Mayor Defends City's Economy, Calls Criticism 'Old and Tired,'" New York Times, July 20, 1966.

[2] Quoted in Steven V. Roberts, "Slums Here Held Federal Problem," New York Times, May 6, 1966.

[3] Quoted in Barbara Carter, "Biggest Slumlord on the Block," Reporter 26 (January 4, 1962), p. 28.

courage Lindsay's successors, Abraham Beame and Edward Koch, from pledging to achieve similar goals, albeit with a new set of bottles for the city's old wine.[4]

In pursuing these ambitious development goals, the older cities are severely handicapped by their limited ability to concentrate resources. Nowhere are the obstacles to concentrating resources better illustrated than in the region's major cities. As a result, several components of the "concentrating" variable are highlighted in this chapter. In particular, we examine the implications for city influence on development of:

1. the shortage of land available for development in the older cities;

2. endemic conflict within diverse populations over development goals and priorities;

3. inadequate financial resources and growing fiscal crisis;

4. the cities' heavy dependence on the states for authority and resources to undertake substantial development programs; and

5. the lack of effective integration of government agencies having responsibilities for urban development.

Before considering these factors in detail, we explore the political implications of the ambitious development goals of the older cities, and examine the role of areal and functional scope in shaping the politics of development in these jurisdictions. The analysis in this chapter draws primarily on New York City illustrations. The next chapter, which examines the efforts of the older cities to concentrate resources by creating autonomous agencies to undertake urban renewal, focuses mainly on the changing role of the Newark Housing Authority.

Goals and Resources in the Older Cities

The nature of the older cities' goals complicates the problem of concentrating resources effectively. In contrast with the development objectives of most suburbs, city goals often require substantial intervention. Suburbs rely heavily on regulating the private marketplace to achieve their main objectives—through zoning, building codes, and other local policies restricting the activities of private developers. Moreover, the overriding goal of many suburbs is negative: the exclusion of unwanted development. Cities, on the other hand, primarily pursue positive objectives. Their basic goal is the attraction of needed development, which requires more active and extensive governmental involvement than is typically the case in suburbia.

[4] See, for example, Beame's "new" economic development program unveiled at the end of 1976 in Economic Recovery: New York City's Program for 1977–1981, NYC DCP 76–30 (New York: December 1976), and Michael Sterne, "A Plan to Revitalize New York's Economy Is Offered by Beame," New York Times, December 21, 1976. To be sure, all public officials in the older cities do not share this activist perspective. One recent exception is Roger Starr, Housing and Development Administrator in the Beame administration, who has argued that New York must adjust to economic and social trends and accept a diminished role in the region and nation; see Roger Starr, "Making New York Smaller," New York Times Magazine, November 14, 1976, pp. 32–34, 99–106. Starr, however, was neither an elected official, nor a candidate at the time he expressed these views; instead he was a professor at New York University.

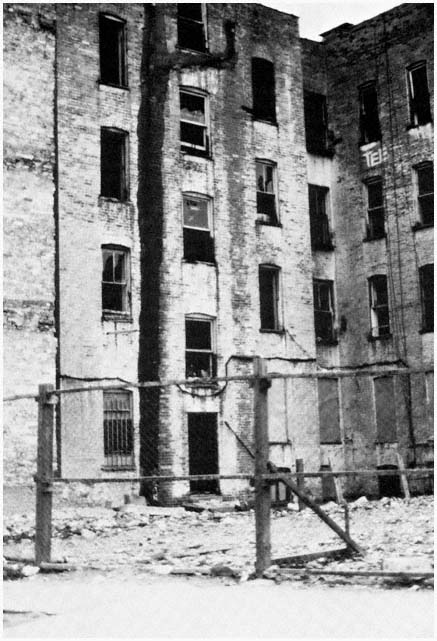

Abandoned housing in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville

section of Brooklyn, a stark symbol of the spreading

decay of vast areas of the region's core.

Credit: Michael N. Danielson

To be sure, cities rely heavily on zoning and other regulatory devices when market forces push in the same direction as city policy, most notably in the case of office buildings and luxury housing in Manhattan. With respect to office construction in the Manhattan business district, Mayor Lindsay defined his city's task as "provid[ing] office space for the corporate headquarters that already are here and want to expand and for the new companies that are interested in moving in."[5] To provide space for new office buildings, New York has been willing to adopt a limited, facilitating role, adjusting its zoning code to meet the requirements of United States Steel, New York Telephone, and other major corporations. And when zoning has been insufficient to facilitate office development, New York City has responded with other actions. In lower Manhattan, for example, the city has moved a park and closed a number of streets to provide "superblock" sites for massive new office buildings.

But most city housing programs and economic development efforts require a far more active role for government. Without substantial public involvement, private builders are unwilling to undertake low- or middle-income housing, or even luxury housing in Manhattan. By 1980, practically no apartment construction in New York City was possible without public assistance of some kind.[6] Thus, to spur the construction of housing for most of their residents, older cities must provide tax abatement, mortgage assistance, and other kinds of subsidies. In the case of industry, older cities are trying to alter rather than facilitate market forces. Zoning by itself is too passive an instrument to attract industry to the older cities. As a result, cities have developed an assortment of other policies aimed at attracting industrial development. Low-interest loans have been advanced for plant expansion and the development of new industries. City-owned land has been made available to industrial firms at bargain rates. An even more activist approach has been public acquisition and development of industrial sites, such as the Flatlands Urban Industrial Park in Brooklyn, which New York City hoped would lead to the creation of 7,000 jobs.

As development goals require more public intervention, the problems of concentrating resources intensify for older cities. Activist policies multiply the number of local agencies involved, and in the process complicate the tasks of those who seek to integrate planning, policy-making, and implementation. New programs frequently involve securing authorization from the state, and usually rely heavily on federal or state funds, all of which increases the number of involved parties and complicates the process. Intervention also typically places new demands on the city's scarce financial and land resources, and this in turn increases conflict over the city's development goals, priorities, and means of implementation.

Ability to concentrate resources also is reduced by the variety of development objectives pursued by most older cities. Multiple goals compete for scarce resources, as well as further increasing the number of participants and relationships in the development process. Nor are different goals always com-

[5] Seth S. King, "Mayor Discounts Loss of Industry," New York Times, February 19, 1967.

[6] For a useful review of the extent of governmental involvement in housing in New York City, see Michael Goodwin, "As Housing Problems Increase, Experts See Little Hope for Future," New York Times, January 23, 1980.

patible. For example, there is no easy way to reconcile the "crucial challenges" posed in New York City's master plan of retaining the middle class while upgrading the position of the poor.[7] If upgrading the poor involves dispersing public housing into more attractive neighborhoods, as advocated by the Lindsay administration, middle-class resistance is certain to be substantial, with residents of the affected area loudly threatening to depart for the suburbs unless City Hall spares their communities from an "invasion" of ghetto dwellers. Moreover, housing programs aimed at either the middle class or the poor are bound to compete for funds and land. And housing of any kind will contend with other development objectives for these scarce resources. Consider the impact on industrial development of the urban renewal program in New York City, whose primary objective was increasing housing opportunities for affluent families. Between 1960 and 1963 alone, urban renewal claimed land containing almost six million square feet of loft and factory space.[8]

Broad policy objectives—such as retaining the middle class—may also embody difficult internal contradictions. Most of the middle-income housing built under New York's Mitchell-Lama program has been located in the outer reaches of the city, where land is relatively inexpensive and relocation problems minimal.[9] Peripheral locations were also attractive to middle-class families who wanted to separate themselves from lower-income and minority areas. Construction of large middle-income projects along the city's outskirts, however, compromised another development objective—the creation of stable, integrated neighborhoods in the older middle-class sections. The location of the massive Co-op City project in the northeast corner of the Bronx, for example, attracted large numbers of residents from the borough's Grand Concourse area who, in the words of the project's developer, were "running from changing neighborhoods."[10]

Conflicts over these middle-class objectives precipitated a "bloody fight" among city housing officials over a Mitchell-Lama project in Brooklyn. Some officials feared that such a large development on the fringe of Brooklyn "would attract many white families from central Brooklyn who felt threatened by the gradual entrance of Negro families into their present neighborhoods," and whose departure would "leave these neighborhoods highly unstable and ripe for real estate speculators."[11] Faced with this dilemma, City Hall opted for new housing—represented by the Twin Pines Village project—over older neighborhoods, on the grounds that the older "white areas are going to change

[7] See Plan for New York City, Vol. I (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1979), p. 5.

[8] See Barry Gottehrer, New York City in Crisis (New York: Pocket Books, 1965), p. 92.

[9] The Mitchell-Lama program was established in 1955 by New York State's Limited Profits Housing Act. Under the program, housing developers who agreed to limit their profits (to 6 percent of equity originally, later to 7.5 percent) were eligible for long-term low-interest loans from the city or state government, and for local real-estate tax abatement. Mitchell-Lama underwrote the construction of 120,000 apartments in New York City through 1979, with 60,000 financed by the city and the rest by the state.

[10] Harold Ostroff, executive vice president, United Housing Foundation, as quoted in Steven V. Roberts, "Co-op City Blend of Races Sought," New York Times, April 30, 1967. Co-op City with 15,500 units was the largest Mitchell-Lama development and one of the largest housing projects in the United States.

[11] . Steven V. Roberts, "Project for 6,000 Families Approved for Canarsie Site," New York Times, June 28, 1967.

Ground is broken for Co-op City in the Bronx,

the largest of the housing projects built under the

Mitchell-Lama program. Among the prominent shovelers were Robert Moses

(in the hat, second from the left), and

Governor Nelson Rockefeller (under "Governor" in the sign).

Credit: Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority

anyway. . . . [I]f we are going to keep middle-class families of all races in the city, we have to provide them with adequate housing choices. Co-op City and Twin Pines Village do that."[12] Within a few years, however, rapidly escalating construction costs and insistent pressures from established middle-class areas led to a deemphasis of new housing, and higher priorities for stabilizing and improving existing neighborhoods.

Goal conflicts in the older cities reflect the complexity of their problems, as well as the lack of proven answers to these problems and an inability to foresee all of the major implications of various policies. Conflicting priorities and incompatible development objectives also result from the responses of political leaders to diverse constituency, agency, and intergovernmental pressures. In almost every policy area, this responsiveness has led to the proliferation of objectives, which makes it extremely difficult to concentrate resources effectively. In public housing, for example, New York has set itself the impossible task of housing as many as possible of those least able to afford satisfactory shelter in the private market, providing public housing tenants with a decent neighborhood environment, and promoting racial and economic integration—while in the process maintaining sufficient political support to fund the program and secure project sites.

[12] Jason R. Nathan, housing and development administrator, New York City, quoted in Roberts, "Project for 6,000 Families."

Areal and Functional Scope

When measured against the size of the entire New York region, none of its older cities has extensive areal scope. New York City covers much more territory than the others, with an area of 300 square miles compared to 24 for Newark and only 15 for Jersey City. But even New York encompasses only 2.4 percent of the 12,700 square miles in the 31-county region. Thus, development efforts in the older cities involve relatively small areas. Moreover, most of their land is already intensively settled, leaving comparatively little for new industry or housing. In the case of open land, New York City's position is more favorable, for it has more undeveloped land than in all the region's other cities. The availability of large tracts in Queens and Staten Island for housing development in recent years permitted New York to retain a much larger share of middle-class families than was the case in Newark and Jersey City, neither of which had much land usable for low-density residential development.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Within the limited areal scope of the older cities are relatively large and diverse populations. Compared to suburbs, cities are both more intensively settled and considerably more heterogeneous. New York City's population density in 1980 was 23,601 people per square mile, compared with 1,504 per square mile for the region as a whole, and 4,603 in the inner ring where suburban settlement is most intensive. The presence of large, diverse, and densely settled populations within heavily developed and geographically contained jurisdictions inevitably intensifies conflict over almost all development issues in the older cities, which contrasts sharply with the situation in most suburbs, where small size and relatively homogeneous populations produce low levels of conflict on development questions.

Limited areal scope has external as well as internal political consequences. As in the suburbs, limited areal scope prevents the older cities from controlling or influencing significantly many activities in the region that affect their interests. But the consequences of the limited governmental influence are more important for the cities than the suburbs because "favorable" development tends to move from the core to suburbia for a host of reasons beyond the control of local government. Unlike suburbs, which generally want nothing to do with the older cities, the cities would like to influence suburban policies, particularly in order to curtail suburban actions that encourage the outward

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

movement of jobs and middle-class residents. The ability of city officials to exercise influence is severely limited, however, both by the region's political geography and by growing suburban influence in the state capitals and in Washington. When the cities and suburbs have common interests—as in aspects of the mass transit issue described in Chapter Seven—they can affect broader regional trends. But when their interests conflict, both must take the uncertain route of seeking help in the state capitals and in Washington.[13]

With respect to functional scope, city governments typically engage in a much wider range of activities that affect development than most suburban jurisdictions. In housing, for example, older cities usually are involved in public housing, rent control, housing rehabilitation, middle-income housing, neighborhood conservation, and urban renewal, in addition to the land-use and building regulation that preoccupy suburban governments. Among the region's major cities, New York has taken on the widest range of responsibilities, encompassing almost every conceivable governmental function with an influence on urban development.

Broad functional scope tends to reduce the ability of the older cities to concentrate resources. With more functions come more specialized public agencies and greater problems of coordination for the mayor and other central policymakers. The wide range of city responsibilities also increases dependence on other levels of government and on public authorities, thus diminishing the cities' freedom of action. State approval has been required for much of the expansion of city functions, and detailed state involvement is common in middle-income housing, rent control, and other policy areas. City programs for economic development, public housing, and mass transit depend heavily

[13] The impact of these efforts on state and federal policy is discussed in Chapter Ten.

on state or federal funds. Moreover, a number of city responsibilities are shared with independent agencies. New York City's government must coexist with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the Urban Development Corporation, and the Port Authority in various policy areas that affect development. In other cities, control over major functions is diluted by the existence of urban renewal agencies, community development corporations, and parking authorities. All of these problems are less severe for suburban governments and for specialized public agencies whose functional scope is narrower than that of the older cities.

The Shortage of Land

Intensive settlement, as indicated above, has left the region's older cities with relatively little land that is easily available for development. Few large tracts of vacant land remain in the cities, except in the more isolated parts of Staten Island and in Newark's meadowlands. Most of the remaining undeveloped land is in small parcels that are difficult to use for large-scale development. Moreover, vacant land in the older cities has usually been bypassed for good reasons—often because of difficult terrain, which requires substantial grading, large amounts of fill, or expensive pilings. Undeveloped areas often lack sewers, streets, access to public transportation, and other improvements. As a result, much of the open land in the older cities is costly to build on, or inaccessible, or both.

The lack of usable vacant land has a number of important consequences for the politics of development in the older cities. It reduces the usefulness of zoning as a means of influencing development, since zoning tends to have its greatest impact when land is initially used. Moreover, the absence of easily developed land combines with intensive settlement patterns to drive up prices, which increases the costs of acquiring land in the older cities for public housing, industrial parks, highways, and every other public project. In addition, most city development programs involve land that is already being used, usually complicating government's role even more. In urban renewal, for example, city officials have to select areas for redevelopment, secure a private developer interested in using the site, acquire the land, relocate those using the property, resell land to the developer, and improve public facilities serving the area, all within the framework of detailed federal regulations.

Intensive development also increases the number of people affected and the degree of conflict, particularly for programs of urban renewal, highways, industrial development, and other activities that require large amounts of land. In the case of urban renewal, more people are disadvantaged by the clearance of densely populated slums than will benefit from the new dwelling units. The fact that very few residents of renewal areas can afford to live in the new buildings further exacerbates discord. Large-scale private development efforts in the older cities cause similar problems. For example, the expansion plans of Columbia University and other major institutions in the Morningside Heights section of Manhattan have been steadfastly opposed by local residents. From Columbia's perspective, "the problem was a physical one. It simply isn't possible for institutions to grow the way the institutions

feel we must grow and for the residents to remain here in the same number and location they are in now. Something has to give and a considerable number of people will have to move."[14] On Morningside Heights as elsewhere in the older cities, however, local residents refused to give in without fighting for their densely settled turf, and in the process successfully enlisted to their cause political leaders who were able to limit Columbia's expansion.[15]

Conflict over scarce land means that most major development activities in the older cities are plagued by long delays. An example is New York City's experience with the Flatlands Urban Industrial Park, the city's initial venture into industrial land development. First, local residents bitterly protested Mayor Wagner's plan to condemn the 96-acre site, and work on the project was delayed while the homeowners carried an unsuccessful legal action all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Then a struggle developed between the city and black groups that wanted the site developed as an educational park complex to foster integration. After years of controversy, instead of being covered by two million square feet of factories as envisaged by City Hall, Flatlands was "a glacier of mouldy mattresses, unsprung sofas, and a strange gamut of debris," populated by "rats . . . as big as cats."[16] When construction finally began in the middle of 1966, Mayor Lindsay was reminded of the intensity of competition for land in the city as he was met at Flatlands by 1,000 black and Puerto Rican demonstrators from Brooklyn's ghettos, who chanted "Industrial Park, No; Educational Park, Yes."[17]

Lindsay sought to mollify the Flatlands demonstrators by insisting that "we can do a lot of things at once. We can do this and still build more and better schools."[18] In fact, however, the scarcity of land in the older cities guarantees that industrial land acquisition will produce conflict. Implementation of Newark's $11 million industrial renewal project in the black Central Ward was delayed for years by the litigation of property owners and the protests of affected residents and their allies, who valued new housing more highly than job development in the renewal area. In New York City's 38-acre Washington Street Market urban renewal area, conflict arose between public agencies pursuing different development objectives. In line with the original plans to develop the Washington Street site for commercial and industrial use, the Public Development Corporation urged the construction of a center for the city's printing industry, which would help to keep the industry's 165,000 jobs in the city. The Housing and Development Administration, on

[14] Lawrence H. Chamberlain, vice-president, Columbia University, quoted in Steven V. Roberts, "Columbia's Expansion to Uproot Area Residents," New York Times, November 2, 1966.

[15] The major victory of local interests over Columbia involved a proposed gymnasium on a two-acre site in a city park that separates Columbia from Harlem. Announced in 1961 and initially supported by most city political leaders, the gymnasium was opposed by a broad coalition of neighborhood and minority interests, leading to second thoughts on the part of city officials, and the plan's ultimate withdrawal in 1969.

[16] Homer Bigart, "Industrial Park Spelled D-U-M-P," New York Times, March 30, 1966. Delays also were caused by difficulties in finding a suitable developer and differences over the project between the Wagner and Lindsay administrations.

[17] See Douglas Robinson, "Mayor Walks Alone into Angry Crowd and Draws Cheers," New York Times, July 20, 1966. Flatlands finally was opened in early 1969; for a useful review of these developments, see Joseph P. Fried, "Park Opens for Industry in Brooklyn," New York Times, January 12, 1969.

[18] Quoted in Robinson, "Mayor Walks Alone."

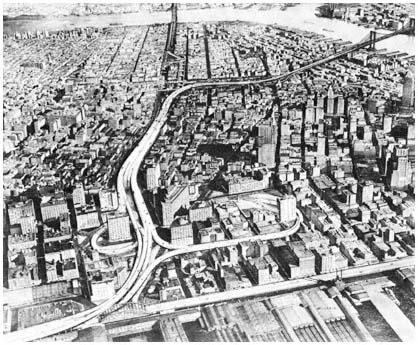

The route of the Lower Manhattan Expressway

as proposed by Robert Moses.

Credit: Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority

the other hand, argued for comprehensive development in the area, including public housing and educational facilities. As with other development projects, conflict caused delays, compounded in this instance because federal and state approvals were required for a change in land use for an urban renewal site.

Nowhere is the impact of scarce land on the politics of development in the older cities more striking than in the case of road building. Highway construction in densely settled sections of the core adversely affects far more people than in the suburbs. A single mile of Robert Moses's Cross-Bronx Expressway demolished 1,530 dwelling units in the East Tremont section of the Bronx.[19] The Lower Manhattan Expressway, another major highway designed by Robert Moses in his capacity as New York's City Construction Coordinator, would if built have displaced 2,000 families and 800 businesses with 10,000 employees along a 2.5-mile corridor between the Holland Tunnel and the Brooklyn Bridge.

As the implications of urban expressways for local neighborhoods were grasped by city dwellers, highway plans met increasingly fierce opposition in the region's core. A lengthening list of projects were shelved in the late 1960s

[19] For an excellent discussion of the routing of the Cross-Bronx Expressway through East Tremont, see Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Knopf, 1974), Chapters 37–38.

and 1970s in the face of intense resistance from local interests and responsive public officials. Successful opposition to the new roads developed sooner in densely settled sections of the cities than in the suburbs, and depended less on the environmental factors discussed in Chapter Four, although antihighway groups in the older cities were quick to capitalize on environmental considerations when ecological concerns moved to the forefront of the debate over road-building in the early 1970s.

The first major casualty among inner-city highways was the Lower Manhattan Expressway. Despite impressive support from downtown business interests, and substantial political backing from City Hall prior to the election of John Lindsay in 1965, the Lower Manhattan Expressway could not survive prolonged and well-organized opposition from residents of the area. First the opponents prevented the construction of the highway for over a decade, then they forced the city to redesign the road as a partially depressed expressway, and finally they persuaded Mayor Lindsay to abandon the project in 1969. The years of controversy and uncertainty also delayed implementation of urban renewal, middle-income and public housing, and other public and private projects in areas adjacent to the stillborn expressway.

In Newark, the Midtown Connector aroused the same kinds of passions as the Lower Manhattan Expressway, with the added element of racial conflict intensifying feelings in the racially divided city. Designed to connect two highways that flanked the city—Interstate 78 and Interstate 280—the 2.5 miles of road were to cut through Newark's black Central Ward, in the process eliminating almost 3,000 residential units housing 10,000 low-income blacks. Initially, the expressway was strongly supported by the city's business and political leaders, who saw the road as a means of relieving congestion, fostering economic growth, and eliminating slums. In promoting the project, Mayor Hugh J. Addonizio emphasized "the benefits Newark will derive from this undertaking," as well as "the necessity" of the road "as part of a large regional transportation network."[20] Opposition began in the affected black neighborhoods, with community, antipoverty, and church groups in the forefront. Other black interests joined in the struggle, including militant organizations like the Black Panthers. By 1970, protests against the road had escalated to the point where city leaders feared a replay of Newark's 1967 revolt, which had been triggered by black anger over the proposed clearance of a large site in the Central Ward for the construction of a state medical school.[21] Facing the prospect of another devastating conflict, city officials reluctantly capitulated to community pressure. As one explained, we "want the road, but we don't want the issue . . . [W]e're not antihighway, but we are anti-confrontation."[22]

Among other major road projects killed by the intensity of opposition in the land-scarce older cities were the Mid-Manhattan Expressway, the Bush-

[20] Quoted in Moray Epstein, "Rt. 75 Line Gets Airing," Newark News, February 28, 1964.

[21] The medical school proposal, community opposition, and the black revolt are discussed in Chapter Nine.

[22] See Douglas Eldridge, "Confidential Report Ready on Rt. 75 Plan," Newark News, February 15, 1970.

Trucks inch their way across Canal Street in the

transportation corridor that would have been

served by the Lower Manhattan Expressway.

Most of the buildings in the photo would have been

demolished to make way for the highway.

Credit: Louis B. Schlivek, Regional Plan Association

wick Expressway in Brooklyn, and the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway.[23] The Cross-Brooklyn road, which was to link the Narrows Bridge with the Nassau Expressway near Kennedy Airport, was the heart of an ambitious "linear city" scheme designed by the Lindsay administration, involving a six-mile strip of new housing, schools and other public facilities, and with commercial and industrial development to be built over the road. The attempt to market the expressway as part of a comprehensive plan intensified rather than reduced opposition, however, since even more land would be taken for the entire plan than for the road alone. Responding to widespread local opposition, legislators from Brooklyn killed the project in Albany. "The people in Brooklyn are up in arms," explained one of the borough's most influential political leaders, because "the Mayor wants to run an expressway through the heart of the residential area of Brooklyn."[24]

[23] The Mid-Manhattan Expressway, joining the Lincoln Tunnel and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, was part of Moses's plan for several elevated highways across Manhattan. The Bushwick Expressway was another Moses project, and was designed to link the Williamsburg Bridge with the Nassau Expressway. Responding to local opposition to the Bushwick road, the Lindsay administration replaced it with the equally unpopular Cross-Brooklyn Expressway.

[24] Assemblyman Stanley Steingut, quoted in Maurice Carroll, "Plans for Brooklyn RoadHalted by Mayor's Order," New York Times, March 4, 1969. Steingut was the leader of the Democratic Party in Brooklyn, and minority leader of the New York State Assembly at the time; his successful effort to block Lindsay's scheme was supported by every member of the state legislature from the borough.

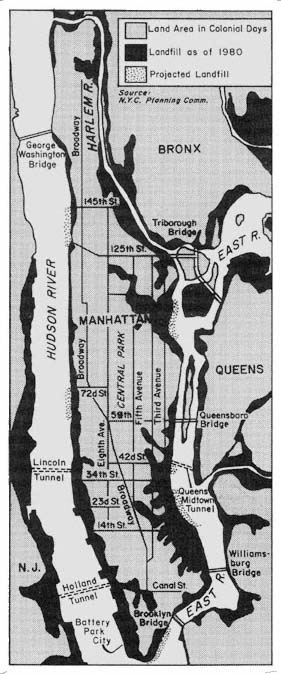

Landfill: Manhattan

and Adjacent Areas

Map 10

One way around some of the problems resulting from the shortage of turf in the older cities is the creation of new land. Over the decades, new land has been formed on both sides of the Hudson by fill and other means, as indicated by Map 10. About 3,650 acres have been added to Manhattan since the city's founding, and land reclaimed from the surrounding waters now accounts for about 25 percent of the island's area. Extensive reclamation has been necessary in the development of marine terminal areas in Newark and Elizabeth. With the growing scarcity of land, its high cost, the problems of relocating residents and businesses, and the intensity of pressures that confront efforts to change existing land uses, the creation of new land has become increasingly attractive to leaders in the older cities. "We're adding more land by means of platform development to lower Manhattan," explained Mayor Lindsay in connection with his ambitious plans for the eastern tip of Manhattan, "because we're not satisfied with the size of the island we bought."[25]

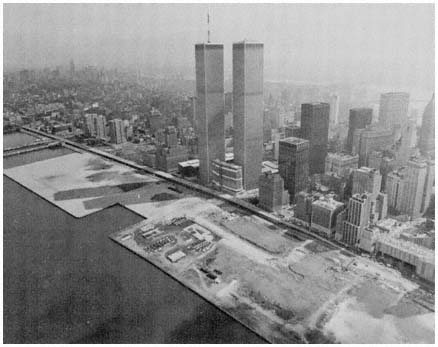

Creating new land, however, does not eliminate conflict. The very scarcity of land in the older cities almost always leads to disagreements over the use of newly formed acreage, as illustrated by the competing plans of New York City and New York State for 91 acres along the Hudson River created in the construction of the Port Authority's World Trade Center. City Hall saw the parcel as an integral part of its comprehensive and imaginative $2 billion plan for lower Manhattan. The state government wanted to develop the site as a $600 million free-standing project called Battery Park City, containing housing, office, commercial, and industrial development. Only after two years of disputes and hard bargaining did a compromise emerge, which retained the state's Battery Park concept, but reframed the project to comply with the city's general plan for lower Manhattan.

Particularly contentious has been the question of what kind of housing should be built on new land. In the case of Battery Park City, the state advocated a mix of housing to serve a broad range of income groups, while New York City favored heavy emphasis on luxury units, because of the high cost of reclaimed land and its desire to complement downtown office development with walk-to-work housing for executives. In the negotiations over the Battery Park project, the city's views on housing prevailed. Less than 7 percent of the project's units were to be for low-income families, and even this commitment disturbed Mayor Lindsay, who saw it as "equivalent to putting low-income housing in the middle of the East Side of Manhattan."[26] Lindsay's position was strongly criticized by black leaders and spokesmen for low-income groups, who assailed the city for using public money to house the rich in "the Riviera of the Hudson" while housing conditions for

[25] Quoted in David K. Shipler, "Massive Complex Planned for Platform in East River," New York Times, April 13, 1972.

[26] Quoted in David K. Shipler, "Battery Park Plan Is Shown," New York Times, April 17, 1969. Because of the high costs of landfill a unit of low-income housing in Battery Park City was about 2.5 times as expensive as the average unit constructed elsewhere in the city.

New land created from the excavation of the

World Trade Center will be the site of the

Battery Park City development.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

the poor deteriorated.[27] A similar dispute arose over the housing mix in the city's Waterside development, involving 1,450 apartments constructed on a six-acre platform over the East River. The controversy combined with financial problems to delay the project for years, before critics were mollified by an increase in the proportion of low- and middle-income apartments.

Conflicting Constituency Interests

As the conflicts over use of newly created land illustrate, the ability of older cities to concentrate resources on development objectives is severely limited by the diversity of their populations. Every major program must run the gauntlet of conflicting interests growing out of class, racial, ethnic, and sectional differences. Rare indeed is the development issue on which the demands of diverse groups are easily reconciled. Efforts to overcome the disadvantages of ghetto dwellers by integrating schools and neighborhoods hasten the exodus of white as well as black middle-class families. Blacks

[27] Percy E. Sutton, borough president of Manhattan, quoted in Shipler, "Battery Park Plan Is Shown." Sutton was the only black member of the New York City Board of Estimate during the development of the Battery Park project. Eventually, as costs for the project rose, all the low-income housing was dropped from Battery Park City.

disagree over whether priority in housing and educational programs should be given to quality or integration. A subsidized transit fare keeps lower-middle-income families in New York City, but also increases general tax burdens, thereby weakening the city's ability to compete for jobs. Affluent whites seek more housing benefits, while poor blacks and Hispanics argue that public efforts should focus on those most in need of improved shelter. Zoning and transportation policies that foster concentration favor the business district's white-collar industries but work against the interests of manufacturers, for whom the costs of congestion offer few offsetting benefits.

In the older cities, socioeconomic differences are bolstered by the spatial separation of populations along income, racial, and ethnic lines. As a result, socioeconomic and territorial interests tend to reinforce each other, as groups and neighborhoods seek to advance their interests on development issues. Spatial differentiation is more important in the cities, because these political units are larger and more diverse than the typical suburb. As indicated in Chapter Three, most suburban jurisdictions are small and encompass relatively homogeneous populations. Thus, while spatial differentiation is important among suburbs, it is not a major political factor within the vast majority of suburban municipalities. In the cities, on the other hand, the spatial separation of socioeconomic groups plays a key role in the politics of development. Local politics is far more territorial in the older cities than in most suburbs, with city councils, party organizations, and many groups based on territorial subdivisions. Political units are particularly important in New York City, whose size, diversity, and history have resulted in its division into 5 boroughs (each with its own president and party leaders), 33 city council districts, 18 congressional districts, 91 state legislative constituencies, and nearly 60 community planning units. Of the 160 local, state, and federal officials elected from constituencies in New York City, all but three represent subsections of the city.[28] As a result, a wide variety of the city's diverse social, economic, and community interests are directly represented in the various political systems that make decisions about development.

Groups also tend to play a more important role in the politics of development in the older cities than in the suburbs. Cities encompass both wider ranges of interests and larger critical masses of individuals with shared concerns than most suburbs. Group interests that can barely fill a living room in a suburb may spawn a dozen organizations in Newark or New Haven, and generate scores of social, religious, civil rights, and community organizations in New York City. The diversity of the older cities also stimulates organization for collective action, since there is much less consensus on development issues than in more homogeneous communities. As a consequence, almost any development proposal is supported and attacked by a variety of group interests—some with broad concerns, others with a very narrow focus; some with considerable experience and resources, others organized hurriedly to block a specific unwanted project. The essential process of group formation, internal organization, and political involvement is no different in the cities

[28] New York's mayor, president of the city council, and comptroller are elected citywide. The five borough presidents and two members of the city council from each borough are elected from these five large subdivisions. All other constituencies are sub-borough, with the exception of one congressional district that encompasses all of Staten Island plus lower Manhattan.

than in the suburbs, but in the older cities the range and intensity of group action on most development issues are substantially greater. Moreover, the scale of the older cities—particularly of New York—means that conflicts tend to attract other groups beyond the immediately affected area, who share interests with those directly involved. As a result, the scale of most conflicts is broadened, further compounding the problems faced by those seeking to concentrate resources on development objectives.

The communications media also play an important role in widening group involvement in the politics of development in the older cities, and especially in New York City, which, as pointed out in Chapter Five, is the primary focus of the region's largest newspapers and major television outlets. In recent years, newspapers and television have devoted increasing attention to local perspectives in highway disputes, housing controversies, and other development issues. In part because of the growing assertiveness of local groups, the press no longer covers most "improvements" from the perspective of the proposing agency, as was usually the case during the heyday of Robert Moses and the Port Authority. And particularly for television, protest activities provide inherently more interesting coverage than the unveiling of a plan. In response to growing media attention, many groups have developed considerable skill in securing coverage of their activities by reporters. The net result is more attention by the newspapers and television news programs to urban development conflicts, which tends to attract still more groups into disputes over housing projects, industrial parks, new roads, and other programs.

Group activity also is stimulated in the older cities by the high level of adversary relations in their political systems. Rival parties and factions are always ready to criticize almost any policy choice by those in power. Complex and fragmented governmental systems ensure conflict among key officials, such as New York's mayor and comptroller. Reinforcing these adversary relationships, of course, are the diverse interests of the city's heterogeneous population. As a result, unified political support rarely is achieved in the older cities for a major project or development program. Opposing groups usually can find a champion among the citywide political leadership, as well as from the elected officials who represent the particular constituency.[29]

To emphasize the role of groups is not to imply that most organizations in the older cities achieve their objectives. Nor does the wide scope of group activity mean that all interests are organized, or that some are not far more influential than others. On one end of the scale are powerful interests, such as the major real estate developers, banks, insurance companies, and contractors, with large stakes in a substantial range of development issues. Few groups in the city can match the financial clout or political access possessed by David Rockefeller of the Chase Manhattan Bank and his colleagues on the Downtown Lower Manhattan Association. Clearly such interests wield considerable influence on many questions, and they have been particularly effective when allied with powerful public agencies such as the Port Authority. But these influential interests do not always prevail in development contests. The strong backing of downtown and other business groups was insufficient to

[29] See particularly Wallace S. Sayre and Herbert Kaufman, Governing New York City (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1960), Chapter 19 and passim .

ensure the construction of the Lower Manhattan Expressway or the location of the World Trade Center along the East River.[30]

Moreover, these influential groups often disagree among themselves on major projects. A good example of elite conflict is provided by the proposed New York City Convention Center, where the contestants have been likened to "a pair of pro-historic beasts" in the form of "two great coalitions of political, real estate, and banking power . . . locked in a tail-thrashing struggle over a new $200-million exhibition center on the banks of the Hudson River."[31] And as is usually the case, the main product of intense group conflict on the convention center was delay, with City Hall unwilling to make a decision between the rival sites that would alienate the powerful groups on the losing side. "No matter what decision he makes, he'll get criticized," explained one of Mayor Beame's aides in connection with the mayor's reluctance to break the seven-year stalemate on the project. "People will say he's choosing a particular site to please this or that political supporter."[32]

At the other end of the scale in terms of political effectiveness in the older cities have been the poor, particularly the minority poor. Large numbers of low-income city dwellers are politically inactive. Meager resources, lack of education, apathy, and alienation make the poor difficult to organize and frustrate sustained political activity.[33] Until the 1960s, those responsible for making development decisions in the older cities were able to shortchange poor blacks and other low-income groups with considerable impunity. Much of the "success" of the urban renewal program in Newark and other cities, discussed in the next chapter, resulted from the inability of slumdwellers to organize effectively to defend their interests. Increasingly in recent years, however, blacks, Hispanics, Italian-Americans, and other low-income residents of the older cities have mobilized the political influence latent in a concentration of people with shared problems. And by flexing their political muscle, the poor have made planning and policymaking more responsive to their needs, while complicating even further the task of concentrating resources in the older cities.[34]

The bitter conflicts surrounding New York City's efforts to scatter low-income housing projects into middle-class neighborhoods illustrate the inter-

[30] The initial plan called for the World Trade Center to face east, toward Brooklyn, Long Island, and Europe. After extensive negotiations with New Jersey officials—whose agreement was required since the Port Authority would build the project—New York political and business leaders finally agreed that, while the gigantic structure could not cross the Hudson River to the wilds of Hudson County, it might traverse Manhattan and face west, toward Jersey City, Newark, and Trenton.

[31] Nicholas Pileggi, "How Things Get Done in New York: A Case History," New York (February 28, 1974), p. 58. Pileggi provides a fascinating look at the interrelationships and conflicts among the major private development interests in New York City and their political allies.

[32] See Steven R. Weisman, "Beame Puts Off Selection of Convention Center Site Until After Vote," New York Times, July 3, 1977. Beame's successor, Edward Koch, finally settled on West 34th Street rather than West 44th Street for the project, whose estimated cost at the time in April 1978 had reached $257 million; see Charles Kaiser, "Convention Site at West 34th Street Chosen by Koch," New York Times, April 29, 1978.

[33] See Michael Lipsky, Protest in City Politics: Rent Strikes, Housing and the Power of the Poor (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1970), particularly Chapters 6–7.

[34] See Chapter Nine; cf Clarence N. Stone, Economic Growth and Neighborhood Discontent: System Bias in the Urban Renewal Program of Atlanta (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1976).

play of these factors. Prior to the mid-1960s, public housing in New York, as in most cities, was confined to slum locations by a combination of federal policies, cost limitations, and political considerations. By locating projects in slums, political conflict over site selection was minimized, since ghetto dwellers needed the housing and other neighborhoods strongly opposed housing projects. The political key to keeping public housing confined to the slums was the role of the borough presidents, who were able to exercise an informal veto over projects in their boroughs. After a site had been selected by the New York City Housing Authority, it was submitted to the appropriate borough president for clearance. Since the borough presidents were highly sensitive to local opposition to public housing, the housing authority tended to steer clear of unacceptable sites in white and middle-class neighborhoods.[35]

Shortly after his election in 1965, Mayor John V. Lindsay attempted to reformulate public housing policy. Lindsay was determined to end "the traditional pattern of huge, sterile public housing projects, isolated physically and socially from community life."[36] In place of ghetto projects, Lindsay sought to foster racial and economic integration by moving public housing out of the slums into middle-class areas. For Lindsay and his aides, scattersite housing was a "moral imperative" dictated by the city's growing racial bifurcation.[37] It was also a response to black interests that had given Lindsay overwhelming support in his race for mayor. Under the new policy, vacant and underutilized sites in outlying sections were to get priority, and borough presidents were to be denied their informal veto over housing projects. "The Borough Presidents have a legitimate knowledge and concern about their boroughs and we intend to consult them regularly," explained a mayoral aide, "but they can't override our final decisions. Public housing has citywide implications and we have to have an overall plan for its development."[38] Lindsay's plan was backed by the borough presidents of Manhattan and the Bronx, who were black and Puerto Rican respectively, and strongly opposed by the other three borough presidents.

[35] The borough presidents exercised an informal veto because of their membership on the Board of Estimate, the more important of New York City's two legislative bodies. Each borough president has two votes on the Board of Estimate, while the mayor, comptroller, and president of the city council have four each. The borough presidents were able to maintain solidarity on most issues before the Board of Estimate through the practice of "borough courtesy," whereby each deferred to the wishes of a colleague whose constituency was directly involved in a matter before the board, in return for similar consideration when their own borough's interests were at stake. This bloc power gave the borough presidents substantial leverage on constituency issues such as site selection. For a general discussion of the political role of the borough presidents, see Wallace S. Sayre and Herbert Kaufman, Governing New York City, pp. 638–639. The role of the borough presidents in site selection for public housing is examined in Jewel Bellush, "Housing: The Scattered Site Controversy," in Jewel Bellush and Stephen M. David, eds., Race and Politics in New York City (New York: Praeger, 1971), pp. 104–106, 110–111. On a similar veto system over public housing sites in Chicago, see Martin Meyerson and Edward C. Banfield, Politics, Planning and the Public Interest (New York: Free Press, 1955).

[36] Quoted in Peter Kihss, "Housing Policy of City Changed," New York Times, July 16, 1967.

[37] Donald H. Elliott, counsel to the mayor and later chairman of the City Planning Commission, quoted in Walter Goodman, "The Battle of Forest Hills—Who's Ahead?" New York Times Magazine, February 20, 1972.

[38] Donald H. Elliott, quoted in Steven V. Roberts, "City Hall Ends Veto by Borough Presidents over Housing Sites," New York Times, May 11, 1966.

As the first step in the new approach to locating public housing, thirteen projects were proposed in 1966 for white middle-class areas in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. Reaction from the affected communities was overwhelmingly negative, with local residents angrily equating public housing with slums, crime, drugs, blacks, and neighborhood deterioration. At meeting after meeting on the scattered site projects, the message of local groups and their political representatives was always the same. "Do not change the area," pleaded a state assemblyman from Queens: "Do not give us a project. We are happy and want to stay that way."[39] At one stormy session of the City Planning Commission, several hundred opponents to scattered-site housing carried placards reading "Destroy a Community and You Destroy a City," "Low-Income Housing Breeds Slums," and "Essential Services Yes, Public Housing No."[40] Never far in the background was the threat of departure as voiced by a Bronx state senator: "This project will promote nothing but the further flight of the middle class from the city."[41]

In the face of this intense opposition, little headway was made with the scatter-site program, as the dissident borough presidents and their allies on the Board of Estimate killed most of Lindsay's proposals. In 1972, six years after the new policy was inaugurated, only one of the thirteen projects had been completed—a project for the elderly, which in New York and elsewhere has been more acceptable politically than family housing with its heavy proportion of black and Hispanic tenants. Two other projects were under construction in white, middle-class areas. And one of these—located in the largely Jewish, middle-income area of Forest Hills in Queens—was the source of an extremely bitter and wide-ranging conflict that eventually sealed the doom of Lindsay's scatter-site program.

Public housing was being built in Forest Hills in 1972 only because local groups successfully kept the project out of nearby Corona. Earlier, a deal had been struck between City Hall and the Queens borough president which switched the project to Forest Hills. Because of this agreement, the Forest Hills Residents Association and other opponents were unable to kill the project in the Board of Estimate. Local interests also failed to block the project in court, although their legal actions delayed ground-breaking until 1971. Meanwhile, the city was enlarging the size of the project from four 14-story buildings to three 24-story apartment towers with 840 units, making Forest Hills more than twice as large as the typical scatter-site development planned by the Lindsay administration.[42] By the time construction finally began, local feelings had risen to a fever pitch, and more than 500 angry demonstrators marched on the site. With the crowd shouting "Keep the ghetto out of Forest

[39] Assemblyman Sidney Lebowitz, quoted in Steven V. Roberts, "Public Housing in Middle-Class Areas Assailed," New York Times, June 2, 1966.

[40] See Emanuel Perlmutter, "Queens Borough President Among 200 Opposing New Low- Rent Housing," New York Times, September 12, 1967.

[41] State Senator Harrison J. Goldin, quoted in Steven V. Roberts, "Public Housing in Middle-Class Areas Assailed," New York Times, June 2, 1966. Goldin was elected city comptroller in 1973.

[42] The change in plans resulted primarily from the higher foundation costs incurred because of adverse subsoil conditions at the Forest Hills site. By building higher and including more apartments, these costs would be spread over more apartments, thus helping to keep the average cost per unit within federal limits.

Hills," and carrying placards declaring "Lindsay Is Trying to Destroy Queens. Now Queens Will Destroy Lindsay," rocks and flaming torches were hurled at the construction trailers.[43]

In the wake of this fiery outburst, the conflagration at Forest Hills spread rapidly, ultimately attracting a wide range of groups and elected officials. One reason for the escalation was the pervasive fear of public housing in white neighborhoods throughout the city. Another was the personal identification of an increasingly unpopular Mayor Lindsay with scatter-site housing, which was seen as another indication of the indifference of Lindsay and other "limousine liberals" to the interests of middle- and working-class whites. Most of Lindsay's numerous political enemies eagerly rallied to the defense of Forest Hills. Widespread press coverage followed in the wake of the vehement demonstrations, spreading from the local press and newscasts to network news programs and national news magazines. The conflict mobilized a wide range of Jewish groups in opposition to the Lindsay program, including the Queens Jewish Community Council, the Long Island Commission of Rabbis, the New York Board of Rabbis, the Association of Jewish Antipoverty Workers, the National Council of Young Israel, and the Rabbinical Council of America. On the other side, black groups—such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the New York Urban League, and the Architects Renewal Committee for Harlem—defended scatter-site housing, as did the New York Urban Coalition, the Queens Council for Better Housing, and one major Jewish civil rights group, the Anti-Defamation League.

As the conflict widened and groups became increasingly polarized over the issue, Lindsay bowed to the mounting pressure and accepted the necessity for compromise. In naming a mediator to explore possible alternatives in Forest Hills, Lindsay conceded that "the climate is just too destructive for our city and the future of our housing programs and community stability, so that we must try yet another way to resolve this matter in fairness to all concerned."[44] Three months later Lindsay reluctantly accepted a compromise plan that cut the size of the Forest Hills project in half, which further delayed construction as the proposal was recycled through the maze of public agencies with responsibilities for public housing in New York.[45] And the high political costs of the intense group conflict over Forest Hills effectively killed Lindsay's scatteredsite program, as well as dealing the mayor a devastating political blow that contributed significantly to his decision not to seek a third term in 1973.

As more and more constituency interests are represented in the development process, political leaders in the older cities find it increasingly difficult to carry out coordinated plans to meet housing and job development needs.[46]

[43] See "Rage in Forest Hills," Newsweek 78 (November 29, 1971), p. 82; and "Fear in Forest Hills," Time 98 (November 29, 1971), p. 25.

[44] Quoted in Murray Schumach, "Mayor, in Compromise Move, Names a Lawyer to Study Forest Hills Plan," New York Times, May 18, 1972. The mediator was Mario R. Cuomo, a Queens lawyer, who later served as New York's secretary of state under Governor Carey and ran unsuccessfully for mayor in 1977.

[45] For a detailed account of the development of the Forest Hills compromise, see Mario R. Cuomo, Forest Hills Diary: The Crisis of Low-Income Housing (New York: Vintage Books, 1975).

[46] For a discussion of the impact of fragmentation in older cities, see Douglas Yates, The Ungovernable City: The Politics of Urban Problems and Policy Making (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1977).

Instead of comprehensive schemes devised by housing, planning, transportation, and industrial development agencies—singly, or preferably with collaboration across agencies—city governments typically wind up with patchwork programs aimed at satisfying the competing interests of diverse constituencies. A good example of the result of these kinds of pressures is New York's Washington Market urban renewal plan, which started off as renewal for the printing industry and wound up being "parceled out . . . in the best New York tradition [with] a community college, an industrial complex, middie-income housing with some subsidized low income units, luxury housing and office buildings—each marked off by the tidy boundaries of compromise."[47]

The Fiscal Straitjacket

Money constitutes a major constraint on the ability of all the region's older cities to concentrate resources. Large public investments are required for the cities to realize most of their ambitious development goals. Local financial resources for these purposes, however, are hard to find because the older cities have been caught in a tightening squeeze between rapidly rising costs and a stagnant tax base. Between 1957 and 1977, New York City's operating budget rose from $2 billion to $13.6 billion while the city's population was declining by 270,000, or 3 percent. During the same period, spending in Newark increased from $82.4 million to $216 million, and the population dropped 17 percent. Part of these increases in public expenditures is attributable to factors affecting all governments in the region: growing demands for public services, rising prices, and increased labor costs without corresponding increases in productivity. But an additional factor of great importance in the older cities has been the steady increase in the proportion of poor people in the core, causing welfare and other social expenditures to consume an ever-larger share of the city tax dollar.

In New York City, these expenditure trends have been amplified by the size of the local public sector, which reflects the city's huge population and intensive settlement pattern. Size increases unit costs because of the need for elaborate organizations to provide education, police protection, sanitation, and other public services. A densely settled population and the massive concentration of business activities necessitate heavy public outlays for mass transit and sophisticated fire-fighting equipment, as well as contributing to high land costs that affect all public activities. The enormous size of New York's public sector also results from the responsiveness of the local political system to human needs. New York spends far more per capita for health care, welfare, social services, and higher education than other major cities. A final factor has been the political power of the city's public employees, which enabled them to claim a steadily larger share of New York's budget from the mid-1950s through the mid-1970s.[48]

[47] "The Washington Market Plan," editorial, New York Times, August 1, 1968.

[48] These characteristics of New York City's politics are examined in Lyle C. Fitch and A.H. Walsh, eds., Agenda for a City (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage, 1970). See also Thomas Muller, "Economic Development: Dealing with Contraction," New York Affairs, 5(1978), pp. 23–36, and other articles in this issue.

Rising costs have steadily squeezed the older city's tax base, which has not grown nearly as fast as local outlays. Underlying the lack of substantial growth in city tax resources, of course, has been the departure of businesses and better-off families to the suburbs. Further complicating the cities' financial problems has been the concentration of the region's tax-exempt property within their boundaries. Governmental, educational, health care, religious, charitable, and other tax-exempt activities occupy much more property in cities than in all but a few suburbs, and the proportion of tax-exempt city land has been steadily increasing. In New York, 40 percent of all property was exempt from local property taxes in 1976, up from 28 percent in the mid-1950s. Newark faces an even more serious problem, since more than 62 percent of its land is tax exempt. Between 1968 and 1976, the number of taxexempt properties in Newark rose from 2,700 to 6,900. In addition to the city governments themselves, the large public authorities are major holders of tax-exempt property in the region's older cities. The Port Authority occupies about one-fifth of Newark's land area. In the early 1970s these facilities generated $1 million annually in lease fees, compared to $64 million if the Port Authority were taxed at the same rate as other property owners in Newark.[49]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The further city tax bases have lagged behind expenditures, the more city governments have had to raise tax rates and find new sources of income. Increasing local taxes, however, has been highly counterproductive to the cities' development goals. Tax rates which are much higher than those in the suburbs, and in other sections of the country, substantially increase the likeli-hood that businesses and middle-class residents will leave the region's cities. Nowhere is this process more advanced than in Newark, whose property taxes are the highest in the nation, reaching $10 per $100 of assessed valuation in 1976. With tax rates this high, only 88 percent of Newark's potential property tax revenues are collected, and 1.5 percent of its taxable properties is aban-

[49] On the financial arrangements between the Port Authority and Newark, see the testimony of Newark Mayor Kenneth A. Gibson and Port Authority Chairman James C. Kellogg III in State of New Jersey, Autonomous Authorities Study Commission of the State Legislature, Public Hearing (Trenton: March 12, 1971).

doned annually. Real estate taxes in New York City have not lagged far behind, increasing from $4.41 per $100 in 1964 to $8.75 in 1980.

To ease the burdens on property owners, cities have sought revenue sources less damaging to their competitive positions. Such taxes are difficult to find, as Mayor Lindsay learned in 1966 when he sought $520 million in new levies, including a city income tax applicable to nonresidents, and a substantial increase in the city's stock-transfer tax. Manhattan's business leaders reacted negatively to both proposals, arguing that raising taxes would undermine the city's ability to maintain its position as the nation's business capital. Particularly vehement in its opposition was the securities industry, whose perceived dependence on a Manhattan location had singled it out for special tax treatment over the years. Lindsay's proposed 50 percent hike in the $100 million stock-transfer tax was denounced as "misguided, short-sighted, and self-defeating" by the New York Stock Exchange, which raised the specter of departure of the security industry's 400,000 jobs and $2.5 billion payroll should the tax proposal be enacted.[50] To bolster its threat to depart, the exchange scrapped plans for a new $80 million headquarters in lower Manhattan, raised the possibility of establishing a second trading floor in New Jersey in order to avoid the New York tax on large stock transactions, and encouraged other cities and suburbs to offer alternative sites and tax advantages. In the face of these moves City Hall eventually backed down, settling for a smaller increase in the tax, and substantial tax concessions for nonresidents and for transactions involving large blocks of stocks.

These economic and political impediments to raising local taxes resulted in annual net tax increases of only 5 percent in New York City for the years after 1960, while city expenditures were increasing by 10 to 15 percent each year. Part of this gap was closed by increased assistance from Albany and Washington, the rest by borrowing and fiscal legerdemain. New York City began borrowing to meet operating expenditures in 1965 during the final year of the Wagner administration. A heavy price was paid for this new policy, since the city's credit rating was lowered immediately by Moody's Investors Service and Dun & Bradstreet. Moody's justified its action by arguing that "there is increasing evidence that over the years the city government has tended to succumb to the pressures of special interests and minority groups, thus permitting spending to get out of hand."[51] The following year Standard & Poor's followed suit, emphasizing the city's vulnerability "to loss of taxpaying businesses and middle-to-upper income families."[52] The reduced ratings combined with a tightening money market to force New York to pay 50 percent more interest for all its loans in 1966 than it had the previous year. In 1967, Newark's credit rating was downgraded as a result of its worsening financial problems, and by 1975 the city had one of the lowest bond ratings of any major public instrumentality in the nation.

Mayor Wagner's borrowing practices were roundly criticized by the two men who would follow him into City Hall. John Lindsay railed against Wagher's financing policies throughout his successful mayoralty campaign in

[50] Keith Funston, president, New York Stock Exchange, quoted in Richard Phalon, "Funston Terms Tax Misguided," New York Times, March 4, 1966.

[51] Moody's Bond Survey, July 18, 1965, pp. 6–7.

[52] Standard & Poor's, July 25, 1966, p. 7.

1965. Abraham Beame, the city's comptroller, condemned bond financing of operating expenditures as an "unsound proposal which threatens the credits and financial standing of the city."[53] But both Lindsay and Beame turned increasingly to short-term borrowing as city budgets soared in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In order to "balance" its budgets and reassure lenders, the city "fudged its books to hide the extent of its borrowing."[54] By 1975, New York was spending 17 percent of its budget for debt service, and the city's deteriorating financial situation led to the suspension of its credit rating, an inability to market new bonds, a failure to meet existing fiscal obligations, and a dire fiscal crisis that further undermined the city's ability to achieve its many development objectives.

In the painful aftermath of the fiscal collapse of 1975, New York City struggled to develop policies that would be least harmful to its basic development goals. Higher taxes were inevitable, despite the certainty that increased taxes would speed the departure of jobs and more affluent residents. Initially the Beame administration sought to increase revenues through a heavy reliance on additional business taxes, including higher stock-transfer, bank, and corporation taxes. As in the past, business reaction was extremely negative, with major economic interests arguing that additional taxes were totally counterproductive for a city whose appeal for business investment was fading rapidly. More than three dozen large corporations had moved their main headquarters out of New York City in the years 1965–1975, and during the Beame regime one survey of corporate leaders in the city predicted "a tidal wave exodus of large corporations" unless city taxes were lowered rather than raised.[55] In response to these warnings and strong business pressures, Mayor Beame completely reversed his approach to business taxes. By 1977, Beame was advocating tax cuts as the major element in his economic development program, including repeal of the stock-transfer tax and credits for new enterprises locating in the city.[56] A year later, his successor, Edward Koch, worked

[53] Quoted in Steven R. Weisman, "How New York Became a Fiscal Junkie," New York Times Magazine, August 17, 1975, p. 8.

[54] "A Healthy Shock for City and Nation," editorial, New York Times, April 7, 1977. See also U.S. Congress, Congressional Budget Office, New York City's Fiscal Problem: Its Origins, Potential Repercussions, and Some Alternative Policy Responses, Background Paper No. 1 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975); Ken Auletta, The Streets Were Paved with Gold (New York: Random House, 1979); and Charles R. Morris, The Cost of Good Intentions: New York City and the Liberal Experiment (New York: Norton, 1980).

[55] See Michael Sterne, "Corporations Fret About New York Tax," New York Times, March 3, 1977. The survey was conducted by the Labor Committee of the New York State Senate. Similar findings emerged from a survey of business leaders conducted by the New York Times in 1976; see Michael Sterne, "Lower Taxes and Better Government Called Keys for City to Hold Industry," New York Times, May 16, 1976. The tally of corporate departures, 1965–1975, was based on the "Fortune 500"; during this decade, the number of these corporations with their headquarters in New York City dropped from 128 to 90. See "Exodus of Corporate Headquarters from New York City: What Impact?," Civil Engineering 48 (November 1978), pp. 97–98.

[56] See Michael Sterne, "Beame Proposes New Business Tax Cuts as Lure," New York Times, May 25, 1977. The stock transfer-tax was to be phased out over four years, and cuts totalling $100 million made in taxes on business property, corporation profits, commercial rents, and new equipment. New firms would be given tax credits against the city's business income tax for each job created, and real-estate taxes held constant for at least 10 years. See also Mayor Beame's program as set forth in Economic Recovery: New York City's Program for 1977–1981 (New York: Department of City Planning, DCP 76–30, December 1976).

feverishly to persuade the state to give the American Stock Exchange an "economic development" grant, and offered other concessions in order to keep the exchange from leaving the city.[57] As the final agreement that kept Amex in the city illustrates, the subsidy approach can generate large benefits for private parties and large burdens for the public exchequer. Government funds will pay for most of the $53 million capital cost for the new Stock Exchange building, with the Amex rent fixed at less than one-half the going rate in the private market.[58]

Reducing financial burdens for some classes of taxpayers inevitably places higher costs on other groups. As a result, tax benefits of this type are extremely sensitive politically, particularly in the complex constituencies of the older cities. For example, New York's efforts to stimulate the construction of luxury apartment developments through tax abatements and other subsidies, as at Battery Park City and Waterside, have been steadfastly opposed by spokesmen for lower- and middle-income groups. As the city's fiscal problems intensified, resentment mounted against the use of scarce public funds to subsidize the affluent. Similar problems arose with middle-income housing, as mounting costs and interest rates led to a steady increase in the income limits for Mitchell-Lama developments. By 1975, a program initially designed to serve families with incomes in the $6,500 to $7,500 range was accepting those with incomes as high as $50,000 annually, to the growing consternation of representatives of lower-income groups. At the same time, escalating operating costs were squeezing lower middle-income residents of Mitchell-Lama housing, many of whom refused to pay the higher charges in an effort to force an increase in public subsidies.[59]

New York City's financial crisis also left substantially fewer resources available for development projects. Capital funds for industrial parks, sewers, and other projects were cut by a quarter in the austerity budget that resulted from the 1975 financial collapse. Similarly, in nearby Yonkers, a city of 200,000 which nearly went bankrupt the same year, "the city's capital projects—longer-range plans to revive a sagging economy" suffered most in the retrenchment of 1976–1978. The fiscal crisis not only slowed physical renewal efforts; the impact was psychological as well, as the "arrested development deprived residents of the feeling that progress was being made and that Yonkers was a city on the move."[60]

[57] For a detailed study of New Jersey's efforts to entice the exchange across the Hudson, and of New York's halting responses, see James P. Sterba, "How New York Almost Lost the Amex," New York Times, November 27, 1978.

[58] See Edward Schumacher, "State Aid for New Amex Building Criticized at Legislative Hearing," New York Times, October 31, 1979.

[59] By the late 1970s, local tax abatement for Mitchell-Lama projects was close to 80 percent. The most militant tenants were the residents of Co-op City in the Bronx, whose refusal to pay increased monthly carrying charges eventually led state officials to agree in 1977 to relieve the project of $25 million of its debt to the state and city; see Joseph P. Fried, "Co-op City Leaders Arrive at Pact with State Aides on Project's Debt," New York Times, July 16, 1977. By the end of the decade, tenant resistance to higher charges had again produced acute financial problems at Co-op City, and was a major factor driving many other Mitchell-Lama projects deeply into the red. See Joyce Purnick, "Growing Deficits Peril Entire Program," New York Times, December 6, 1979.

[60] Ronald Smothers, "Yonkers, With Spending Curbed, Takes Control From State Today," New York Times, November 27, 1978.