The Mask As Metaphor

The Teotihuacán Tlaloc

When we turn from the Valley of Oaxaca to the Valley of Mexico, we move from the realm of Cocijo to the territory of Tlaloc, his younger but far better known "brother." While representations of Cocijo are found as early as Monte Albán I (500-300 B.C.), no full image of the mask of Tlaloc has been found before the Tzacualli phase at Teotihuacán (A.D. 1-150). Significantly, that first, almost sketchlike image appears on an effigy urn,[132] numerous examples of which are found in the archaeological record throughout the history of the Valley of Mexico. Often associated with burials, these urns no doubt had a ritual function since they are similar to those frequently depicted in the hands of painted and sculpted images of Tlaloc; in these depictions, the urns are the containers from which the waters are dispensed by the god, an obvious visual reference to the pan-Mesoamerican mythic attribution of the rains to the urns of the rain god. It is a measure of the fundamental importance of the concept being represented that this early "sketch" reveals, except for its lack of fangs, the mask's essential symbolic configuration, which was to remain the same, in form as well as meaning, through violent social upheavals for 1,500 years until the Conquest and which, we suggest in the final section of this volume, continues to exist in somewhat modified form even today. Thus, that mask of the rain god we call Tlaloc, its Aztec name, "clearly constitutes one of the most generally accepted cases of long-term iconographic continuity in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. Nearly every student appears to regard the earlier images [i.e., those of Teotihuacán] as directly ancestral to the historic Tlaloc" identified by the Spaniards at the time of the Conquest.[133]

As with Cocijo at Monte Alban, the essential

features of Tlaloc coalesced to form that composite mask during the transition from the Preclassic to the Classic period, a stage marked

in central highland Mexico . . . by the coming of age of the largest city of pre-Columbian America, Teotihuacán. It was the dominant political and religious center in the Basin of Mexico for more than five centuries, during which time it exerted far-reaching influences that radiated in various directions over ancient trade routes as far as the Maya area.[134]

The development of that city and its far-flung relations with other areas of Mesoamerica is fundamentally bound up with the symbolic elaboration of the mask of the rain god which moved over those trade routes to appear throughout Mesoamerica[135] as the symbol of Teotihuacán, which was "emphatically the city of Tlaloc."[136] Like Cocijo, Tlaloc was essentially related to lightning and through lightning to both power and the orderly passage of time, as the central image of the god we will discuss demonstrates. Holding a flowing urn displaying the mask of Tlaloc topped by the year sign in one hand and a lightning symbol in the other, he effectively relates sustenance, time, and power in a single compelling image. Through the mask of that god, the massive material entity that was the city thus acknowledged its indebtedness to the world of the spirit, which provided both the order and the sustenance through which its life was maintained.

That Tlaloc can be seen to have been symbolically and conceptually, although not visually, identical to Cocijo strongly suggests their common derivation from an Olmec model, and there are other strong suggestions of Olmec influence at Teotihuacán. "One cannot avoid the impression that in many respects, particularly the abundance of shells and other coastal symbols, the entire Teotihuacán complex was in a sense what might be termed 'Gulf oriented"' as a result of the O1mec "inspiration,"[137] but the precise way in which that inspiration manifested itself in the transition from the Olmec were-jaguar through the village cultures to the Tlaloc of Teotihuacán, often associated symbolically with those "shells and other coastal symbols," is not completely clear. As we have shown, the Olmecs, through relations based fundamentally on trade, exerted a profound influence on those village cultures, an influence that in Oaxaca resulted in the fusion of Olmec with indigenous beliefs and iconography in general and in the development of the Cocijo mask in particular.

There is some evidence of similar developments in the art of the village cultures presumably responsible for the development of the urban center of Teotihuacán:[138] a number of images suggest the Olmec were-jaguar and prefigure the Tlaloc mask. A late Preclassic "proto-Tlaloc effigy" urn from Tlapacoya,[139] for example, displays a distinctly O1mec mouth, a result of the Olmec influence in the middle Preclassic. [140] And, as Grove points out,

a Middle Preclassic goggle-eyed Tlaloc face exists among the paintings at Oxtotitlán cave. A more tenuous example occurs at the extreme top of the Cerro de la Cantera, Chalcatzingo, while several other Tlaloc paintings, also possibly Middle Preclassic, exist at the same site, ... suggesting that the goggle-eyed Tlaloc visage is part of the indigenous altiplano belief system which in the Middle Preclassic had fused with the [Olmec] belief system penetrating into the altiplano from the Gulf coast.[141]

The coexistence of such Tlaloc-related images with clearly Olmec art at each of these sites marks a point of fusion of the Olmec were-jaguar with the indigenous god-mask since none of the Tlalocs are full representations of the later mask[142] and since the Olmec were-jaguar does not exist in highland art after this period. The bulbous or "goggle" eyes, probably a symbolic feature indigenous to the Valley of Mexico or the result of Zapotec influence, which Grove sees as characteristic of Tlaloc's mask, are also found on the composite masks of other gods at Teotihuacán, indicating that they do not identify Tlaloc unless they are present on a mask with Tlaloc's mouth, a mouth clearly derived from the Olmec were-jaguar.[143] Thus, the Tlaloc mask exemplifies the fusion of indigenous and Olmec motifs, but it also illustrates the complexity of the iconographic systems involved.

And there is another form of complexity that makes understanding the development of the mask of the rain god in the Valley of Mexico difficult. While the art of Teotihuacán with its constant visual references to water surely indicates that "the cult of the rain god was supreme,"[144] not all of the masked figures associated with water and fertility in that art are clearly Tlaloc, although some have features more closely related to the Tlaloc mask than others. The situation has provoked the predictable controversy among Mesoamericanists. Many scholars, especially those in Mexico, hold to the view that all iconographic motifs related to water are also related to Tlaloc. This includes such seemingly diverse elements as "the jaguar, serpent, owl, quetzal, butterfly, bifurcated tongue, water lily, triple-shell symbol, spider, eye-of-the-reptile symbol, cross, and the year sign."[145] Kubler, despite his unwillingness to identify these traits by the Aztec name Tlaloc of over a thousand years later, holds a similar view. At Teotihuacán, he says, "the rain-god cluster is most common, with five or six variants in the representation of the deity, under reptile, jaguar, starfish, flower, and warrior aspects."[146] Pasztory, however, has suggested that such all-inclusive categories "are cumbersome in their breadth."[147] As she demonstrates in her study and as we will demonstrate in a somewhat different way below, it is possible to be more precise:

there is a particular mask with a particular combination of features which can be identified as the essential Tlaloc.

But it is not a simple matter of agreeing with Pasztory and disagreeing with Kubler and the Mexican scholars. The complexity arises from the fact that both are correct. In the case of the rain god, for example, a particular image fusing symbolic references to all of the facets of the world of the spirit for which his mask stands as the metaphor can be identified as central to the grouping of images of Tlaloc to be found in the art of Teotihuacán, but, significantly, there are many variants of this essential Tlaloc mask, all of which were no doubt seen at Teotihuacán as aspects of the god. These aspects of the unitary Tlaloc as well as the aspects of the other gods of Teotihuacán were depicted in stone carvings, ceramics, and paintings, but nowhere were they more beautifully detailed and colorfully rendered than in the murals decorating the inner and outer walls of the city which delineated the full spectrum of the supernatural as it existed for the Teotihuacanos. Of course, relatively little of that spiritual art has been preserved; we must try to imagine its magnificence from the fragments remaining.

For the citizen of Teotihuacán, that spectrum filled his every waking moment, and no doubt his dreams as well, since the city in which he lived was literally covered with painted murals and relief carvings depicting the masks of the gods and symbolically arrayed priests enacting rituals dedicated to those gods, paintings that adorned the inner walls of the apartment compounds and temples as well as the facades of buildings and pyramids. The most magnificent lined Teotihuacán's Via Sacra, the north-south Avenue of the Dead lies in front of the Pyramid of the Sun and connects the Ciudadela at the heart of the city with the Pyramid of the Moon and the Quetzalpapálotl Palace. Along this mural-lined, sacred avenue, which, as we will explain, expressed in its orientation the relationship between man and god by symbolically becoming the vertical axis that joined the world of man to the enveloping world of the spirit, the ritual processions of masked performers, symbolically costumed priests, and musicians with flutes, horns, and drums often made their way. The fragments of the murals that remain allow us to imagine the spectacular beauty and profound significance of those processions in that sacred space. At the height of its magnificence and power, Teotihuacán must truly have seemed the city of the gods that the Aztecs, its distant heirs, thought it had been. And Tlaloc, depicted in those murals in all his varying aspects, was chief among the gods of that painted city.

All that remains of that beauty and significance are the fragmentary murals,[148] but even in their present state they suggest the vitality of the spiritual thought embodied in them by their creators and their function as the "channel of communication" of that thought from the priests to the populace.[149] "Every wall is, as it were, a page out of a unique and splendid codex," which, were it intact, would "hold the key to the spiritual structure of Mesoamerica," according to Séjourné.[150] But unfortunately that "mural codex," as we might call it, is not intact. And even if it were, we would have great difficulty reading its images since they lack even the glyphic notations that accompany the images of the Maya. Lacking such explanatory glosses, we must try to understand the system underlying these images, their organizing principle, which alone can enable us to understand the relationship between them as the Teotihuacano would have, even though we can never hope to understand them in all the intricate detail meaningful only to the initiate. Interestingly, Kubler approaches the Teotihuacán mural codex in exactly this way.

Within each mural composition, a principal theme or figure is evident, enriched by associated figures and by meaningful frames suggesting a recital of the powers of the deity, together with petitions to be granted by the god. We can assume that the images of Teotihuacán designate complex liturgical comparisons, where powers, forces, and presences are evoked in metaphors and images.[ 151]

He suggests that these metaphors and images be grouped thematically to reveal their full significance, a principle that, when coupled with Pasztory's identification of specific images as central to the symbolization of particular gods, provides something like the key Séjourné mentions and indicates the extent to which the mask did function as the central metaphor in the thought of Teotihuacán. Thus, we can identify a particular mask that expresses symbolically the full range of "powers" associated with a specific god as the central image of the god and use it to understand the numerous variant forms that address particular aspects of that full range of power.

Each of the "gods" of Teotihuacán is thus really an elaborate system of god-masks in which each particular mask delineates an aspect of the supernatural continuum identified by the name of that god. The system that is each god is embodied visually in the series of variations of the central mask achieved through the permutation of several symbolic features through the range of their possible combinations, the archetypical Mesoamerican method of systematizing spiritual reality seen in its clearest form in the calendrical systems. Together, all of these variant forms must have been combined in the Teotihuacán imagination to form one mask, the true mask of the god, its essential form that could exist only in the mind—the embodiment within each human being of the world of

the spirit. Just as the multiplicity of being in the world of nature had its source in a spiritual unity and could only be fully understood in terms of that unity mysteriously existing in and through the multiplicity of the created world, so the mask of the god was imagined as a unity but depicted in all its variant forms in an attempt to capture in paint, stone, and ceramic the fullness of that elusive spiritual conception. The mask embodying the "central image" of the god was the closest actual image to the conception, which by its very nature could exist only in the minds of the seers of Teotihuacán.[152]

The first task facing anyone who would understand the Teotihuacán conception of Tlaloc, then, is the identification of a central image of the god in the art of that city. As we suggested above, Pasztory has identified that central mask by working backward from the masks we know were Tlaloc, those Aztec representations identified as such by the Spanish at the time of the Conquest. Following Hermann Beyer,[153] she selects as representative of the god those images of Tlaloc on page 27 of the Aztec-era Codex Borgia (colorplate 1), figures that have "goggled eyes and curving upper lips with fangs, who from one hand pour water from effigy vessels representing themselves and in the other hold an adze and a serpent representing lightning."[154] The images on this page of the codex serve nicely to identify the essential Tlaloc since they relate the god both to water and to the cyclical movement of time, a connection always fundamental to the rain god of the Valley of Mexico. There are five differently costumed Tlalocs, one in each corner and one in the center, which illustrate the Mesoamerican identification of time and space since, seen as a spatial image, they depict each of the four directions and the center. But seen as a temporal image, they depict each of the four points in the daily cycle of the sun and the center around which the sun symbolically moves (see p. 121). The temporal interpretation is further strengthened by the function of this page within the codex which, according to Seler, is to represent the quadripartite divisions of the 260-day sacred calendar and of the 52-year cycle[155] and thus to establish an order for the ritual life of the society. These images, then, in bringing together rain and the orderly passage of time, illustrate the Mesoamerican view of the essential order of the universe through which man's life was maintained and on which man's ritual life must be patterned. These are certainly among the most significant images of Tlaloc in Mesoamerican spiritual art, and we will return to them below in our discussion of the Aztec concept of the god.[156] It is therefore a remarkable, almost incredible, indication of the great significance of this particular image of the god that there are iconographically equivalent figures in the Teotihuacán murals painted a thousand years earlier and equally remarkable that actual effigy vessels, such as the vase we mentioned above from the Tzacualli phase, similar to those held by the Tlalocs of the murals and codices, appear continuously in the archeological record of the Valley of Mexico from the time of Teotihuacán to the Conquest.

If, at the height of Teotihuacán's glory a thousand years before Aztec priests were using the Codex Borgia's esoteric lore for divination and prophecy, we were to have wandered into the apartment compound of Tetitla not very far from the center of the city, we would have found that same image of the masked figure of Tlaloc painted on the lower register of an inner wall near the ceremonial patio of the complex containing the small pyramidal altar, or adoratorio. The image is still there today (colorplate 2a) although the painter, priests, and worshipers are gone, as are the beliefs that bound them together in their ritual activities in that sacred space. Séjourné, who directed the excavation of Tetitla, calls that image a Lightning Tlaloc[157] because it holds in its right hand an undulating spear prefiguring the lightning serpent of later times held by the Codex Borgia Tlalocs. Its left hand clutches an effigy urn with a mask identical to that of the figure holding it, an urn like those from which water pours in other Teotihuacàn images. Though the masks are the same, the headdress surmounting the mask on the urn differs from that of the figure holding it in being "a stylized year sign" made up of "a rectangular panel topped by a triangle between two volutes."[158] This clearly connects this Tlaloc symbolically with the orderly movement of time and, again, with the Codex Borgia Tlalocs as well as with other Aztec Tlalocs who often wear a similar headdress. The headdress worn by the figure holding the effigy vase is mostly gone now, but what remains suggests the plumed headdress with a rectangular headband often seen on Teotihuacàn figures related to fertility.

All of these features, however, find their true significance in the mask-face they frame, and the most striking feature of that mask is the mouth with its curving, pronounced upper lip reminiscent in its prominence and stylization of the Olmec were-jaguar. Under the lip, the gum protrudes and from it come five fangs, the two outer ones long and curving back, the three center ones shorter; that these are the fangs of the jaguar is made clear in the numerous depictions of jaguars with similar fangs in the mural art of Teotihuacàn. From beneath the fangs, in place of a tongue, emerges a stylized water lily with a flower bud on either side, a symbolic motif common in the art of the Maya and one that, by its trilobed form, suggests the bifurcated tongue of Cocijo, a tongue that is, in fact, found on other Teotihuacán images of Tlaloc which lack the water lily. While that tongue is clearly the tongue of the serpent, it is also depicted

in the art of Teotihuacán on the figures of jaguars, thereby suggesting again the symbolic relationship between those two creatures. Thus, the water lily and tongue motifs relate Tlaloc to the Olmec rain god in their jaguar connotations but also to his Maya and Zapotec analogs through the Maya water lily and Cocijo's serpent tongue.[159] On either side of and slightly above the mouth are the exaggerated ear flares composed of two concentric circles which are depicted on long, narrow ear coverings attached to the headdress, ear coverings similar to those worn by San Lorenzo Monument 52 (pl. 4), the Olmec Rain God CJ. Still higher than the ear flares and directly above the mouth are the typical goggle eyes of Tlaloc, with what is perhaps the suggestion of an actual eye within them. The "goggles" are also concentric circles and echo visually the ear flares as well as the eyes of the Cocijo mask.

This, then, is the central image of Tlaloc, identifiable by its symbolic reference to the essential powers of the god and to the rain gods of the other cultures to which it is related. It is significant that this particular mask, like many of the other Tlaloc masks in the art of Teotihuacán, has been stylized to the point of depicting only mouth, ears, and eyes—a stylization with enormous symbolic overtones regarding the interaction of the gods with the world of man and nature. Since each of the forms of which it is composed are found separately in the art of Teotihuacán, each of them must be seen as individually symbolic, and their combination in a single mask results in a symbolic statement that is, at least in one sense, the "sum" of those individual meanings. If one feature were changed, as we will show, the statement would be different. Significantly, each of those separate forms making up the mask represents one of the sensory organs through which human beings relate the external reality of nature to their own inner being and, conversely, in speech and through the expressions of mouth and eyes, communicate their own inner realities to the external world. These organs and the signs that represent them in the symbolic art of Teotihuacán refer directly, then, to that liminal point at which inner and outer, matter and spirit merge, a constant symbolic preoccupation of Mesoamerican art for which the mask is the primary metaphor and one often associated, as we have shown, with the rain god. In its stylization, then, the Tetitla Tlaloc serves also as a central image of the god by emphasizing the symbolic features of his mask. It is as close as human creativity can come to rendering "the thing itself," the true image of the god, the precise delineation of that particular meeting place of spirit and matter.

Thus, the centrality of this image of Tlaloc, like that of the Codex Borgia images, results from its bringing together symbolically all of the essential qualities of Tlaloc as we know them from the tradition in which he exists: his role as rain in the provision of sustenance, his role as lightning with its implications of the power of rulership, and his role as the driving force behind the orderly movement of time. But there are countless other images of Tlaloc in the art of Teotihuacán, and those other images are variants of this central one, each, no doubt, with its own precise meaning to the priesthood.[160]

A number of those other Tlaloc images are very closely related to the Tetitla Tlaloc. One of them (colorplate 2b) is crucially and centrally placed in the border between the upper and lower parts of the Tepantitla mural (colorplate 3), which we will discuss at length, and is virtually identical to the Tetitla Tlaloc, with one important difference: instead of holding an effigy urn in one hand and a lightning-spear in the other, this Tlaloc holds in both hands effigy urns from which water flows. This iconographic shift surely suggests a change of emphasis; the Tepantitla Tlaloc is concerned primarily with the provision of rain, an emphasis borne out by the mural as a whole, which is perhaps the most extensive and intricate treatment in Mesoamerican art of a ritual involving the provision of water by the world of the spirit to maintain human life on the terrestrial plane. In addition, a profile view of the same Tlaloc, this time a full standing figure, can be seen on a mural fragment now in a private collection.[161] Since the figure is facing left, the painting emphasizes the effigy urn held facing the viewer in its right hand, and in this painting, it is quite clear that the urn is meant to symbolize a container of rain since we see streams of water pouring from it. Still other images of this Tlaloc exist with varying headdresses and holding various symbolic items in mural fragments at Tetitla[162] and at Zacuala, one of them holding a corn plant in a configuration to be repeated until the time of the Aztecs.[163] Similar Tlalocs are found on ceramic figures and figurines,[164] on painted and molded vessels,[165] and on actual effigy vessels found with burials at Teotihuacán.[166]

While all of these Tlaloc masks have a mouth whose upper lip turns under the two elongated outer fangs to join the lower lip, there is another distinctive Tlaloc mouth treatment that seems visually to be derived from merging those two outer fangs with the upper lip, resulting in a lip that looks rather like a handlebar mustache and is not connected to the lower lip, a common feature of post-Teotihuacán Tlalocs and, in fact, much more like that on the Codex Borgia Tlalocs than is the lip of the Tetitla Tlaloc we and Pasztory see as the central image of Tlaloc at Teotihuacán.[167] From beneath that upper lip extends a row of three or four teeth or fangs, usually straight and of the same length. In some depictions of that mouth, an elongated bifurcated tongue, the tongue of the serpent, emerges beneath the fangs. The serpentine tongue in these images replaces the water lily extending from the mouth of the Tetitla Tlaloc, a substitu-

tion that is no doubt symbolically significant since we know of no Tlaloc image with both a tongue and a water lily. While the water lily seems clearly to relate to the god's provision of water since it is generally found in the context of symbolic allusions to rain, the meaning of the bifurcated tongue is more complex. Pasztory sees it as connected "with water and warfare and [sees] a possible relationship with a sacrificial warrior cult,"[168] primarily because it occurs in the border of a mural at the apartment compound of Atetelco containing warriors and a number of allusions to sacrifice, one of which is a jaguar with a bifurcated tongue, a speech scroll, and what is thought to be a representation of a bleeding human heart just outside its mouth. That this is related to sacrifice seems clear, even though the precise significance of the union of jaguar, serpent, and human heart is elusive.

The connection between the Tlaloc with the bifurcated tongue and sacrifice occurs in other contexts as well, though these contexts are not connected with warfare. That Tlaloc is clearly depicted, for example, on a tripod vessel found in Burial 2 at Zacuala[169] alternating with representations of Xipe, a figure also related fundamentally to human sacrifice, in this case, however, as it is related to fertility. The same mask is depicted on a fragment of another tripod vessel[170] alternating with temples on platforms depicted so as to emphasize the stairway and temple entrance, thereby suggesting the sacrificial ritual that in later times would have taken place in precisely that sacred context. Thus, it seems reasonable to relate the tongue to sacrifice on the basis of these examples since, as we have demonstrated above in our discussion of the mask of Cocijo, the serpent is symbolically related to sacrificial blood in later Mesoamerican art, as the massive Aztec Coatlicue created by the heirs of the spiritual thought of Teotihuacán so impressively demonstrates.[171] It seems likely, then, that the serpent-tongued Tlaloc mask is to be found in contexts associated with sacrificial fertility ritual, and as we have shown, this symbolic connection with sacrifice is but one of many connections between the snake and fertility which are ample reason for providing the god of rain with a serpent's tongue.

That alternation between the serpent's tongue and the water lily is symbolically significant, but even a casual glance at the metaphoric cluster of Tlaloc masks that define the god in the art of Teotihuacán will suggest that that is not the only symbolic variation of the configuration of the mouth of that mask. An interesting example of those variations and their possible meaning can be seen in a series of four different depictions of Tlaloc on almenas, or merlons, found in varying locations at Teotihuacán. Designed to line the edges of flat roofs in the manner of battlements, such merlons would have seemed to look down on the ritual activity taking place in the patios and plazas beneath them, seemingly an ideal placement for images of the rain god.

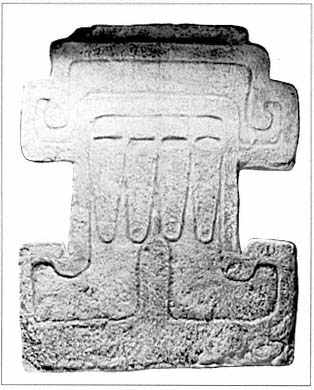

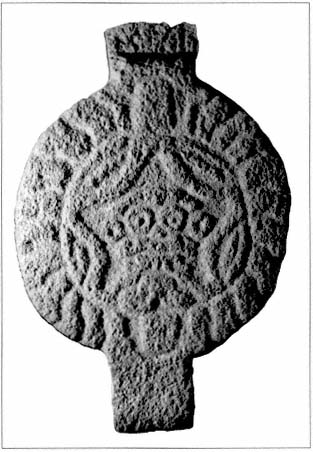

The most abstract of the four (pl. 16) is a stylized depiction of only the upper lip, fangs, and tongue of the mask, indicating clearly that that combination, in itself, had a significant symbolic meaning surely related to the mouth's function in expressing the "inner" reality of people and gods. This variant of the mouth has the "handlebar mustache" upper lip with four long fangs, all of them straight, projecting beneath it. A second version (pl. 17), which is somewhat more realistic but still quite stylized, depicts the face of Tlaloc within a starfish, one of many uses of marine life in conjunction with Tlaloc at Teotihuacán to suggest water. Though this mask also has the handlebar mustache upper lip and an exaggerated bifid tongue, the fangs differ from those on the first example; this Tlaloc has the two long, backward-curving outer fangs enclosing three shorter ones of the Tetitla Tlaloc. But it is interesting and perhaps significant that in an almost identical depiction of this same combination of starfish and Tlaloc in the border of a mural in the Palace of Jaguars,[172] the mask, in every other respect identical to this one, has the turned-under upper lip of the Tetitla Tlaloc.

And the mouth with the handlebar mustache upper lip also exists without the tongue, as can be seen on the other two merlons, perhaps the most

Pl. 16.

Stylized Tlaloc mouth, relief on a merlon, Teotihuacán

(Museo Nacional de Antropología, México).

Pl. 17.

The face of Tlaloc within a starfish, symbolic of water,

relief on a merlon, Quetzalpapálotl Palace, Teotihuacán

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

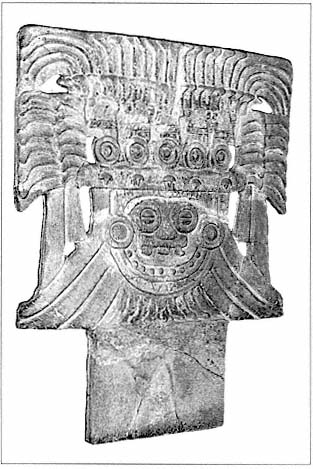

fascinating of which is the one now in the Teotihuacán museum (colorplate 4) which suggests the face of Tlaloc by displaying "goggles," ear flares, nose, and mouth on a flat surface. The handlebar mustache upper lip in this case has three long, tapering fangs reminiscent of those common in depictions of the rain god in the art of Veracruz. The lower border of the merlon might be meant to suggest a bifurcated tongue, but in place of the tongue is an unusual design suggesting vegetation, perhaps the cornstalk often associated with Tlaloc. Also depicted are the hands of the god, and from these hands drops of water fall to the world of man below, suggesting that this mask's combination of features refers to rain and fertility.

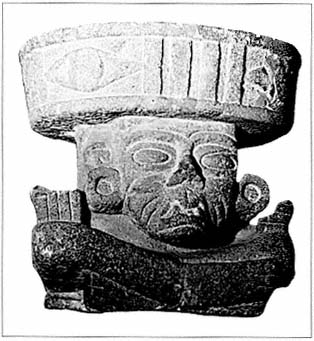

A fourth version of the mouth, somewhat more realistic still, is found on a merlon similarly displaying a headdress, goggle eyes, ear flares, and a beaded necklace (pl. 18). Though the mouth of this mask seems different from that of the preceding Tlaloc at first glance, it is essentially similar. In this version, the upper lip has become a bar, slightly raised at either end to suggest the upturned ends of the more elaborate upper lips, from which descend three short, stubby fangs, the central one straight, the outer two curved slightly back in what might be seen as a further stylization of the Tlaloc mouth. And the mouth of this Tlaloc has no suggestion of a tongue or vegetation symbol at all. That this extreme stylization of the upper lip is a significant one is suggested by the fact that it is found on both the Tepantitla and Ciudadela masks which we will examine below.

Pl. 18.

Tlaloc, relief on a merlon, Teotihuacán

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico).

These four Tlaloc masks carved on merlons, then, illustrate clearly the possibilities of variation in one of the features—the mouth—of the Tlaloc mask. The shape of the upper lip can be either turned under or curved up; the fangs, which can vary in number from three to seven, can be straight and of the same length or the two outer ones can be curved back and longer than the inner ones; and there can be a tongue or a water lily or nothing at all protruding from the mouth. A series of Tlaloc masks constructed through the permutation of the variations in each of these three features—lip, fangs, and tongue—through all their possible combinations would be very large, and when one adds the possible variations of eye and ear form, headdresses, costume, and paraphernalia, the number of possible variations of the Tlaloc mask becomes truly mind boggling. Of course, not all of these po-

tential Tlaloc masks exist in the fragmentary body of Teotihuacán art that now remains, but a significant number do, and certainly many more did exist. There are, then, many more masks of Tlaloc in the art of Teotihuacán than we can discuss here. But such a discussion, while interesting, is not necessary since the variation exemplified by the masks we have discussed, all of them clear examples of Tlaloc as almost all scholars would agree, reveals the underlying principle governing the construction and functioning of the mask and costume as vehicles of metaphorical communication in the art of Teotihuacán. Each of these potential masks formed by the permutation of symbolic features of Tlaloc is to be seen as an aspect of the unitary Tlaloc mask that could exist only in the spiritual imagination of the seers of Teotihuacán, an aspect created by combining particular features of the god to make a precise symbolic statement. Thus, it seems clear that if we are to come to an understanding of the spiritual thought of Teotihuacán, we must understand this fundamental principle by which that thought was formulated and communicated.

Such an understanding also enables us to establish the identity of a number of images that, while containing some of the features of the central Tlaloc mask, also contain others so unusual that scholars have not been able to agree as to the identity of the god being represented. The importance of establishing that identity can be seen in the fact that two of those masks are very significant symbolic aspects of the two most important and celebrated works of painting and sculpture at Teotihuacán: the Tlalocan patio mural at the apartment compound of Tepantitla and the frieze decorating the Temple of Quetzalcóatl in the Ciudadela. If we are to understand the complex symbolic meaning expressed by the interrelationship of a number of symbols in works such as these, we must understand first the masks and other symbols of which they are composed and then the symbolic meaning resulting from their combination. The individual masks, like themes in a symphony or characters in a novel, can be understood fully only in the context of the work as a whole. Perhaps because these particular masks were meant to function within such complex works, they are almost unique and therefore occupy a place at the outer limit of the continuum of masks created by varying the symbolic features of Tlaloc and have been difficult to interpret precisely for that reason.

As we have said, the key to resolving the difficulty lies in understanding the underlying principle by which the masks and the figures wearing them are constructed, and that principle is an extension of the method of varying individual symbolic features which accounts for the range of Tlaloc masks. The god we call Tlaloc was actually a series of variations of a central mask, a metaphoric cluster of god-masks, and there were, of course, other clusters of masks constructed in the same way to represent other gods. Just as each of the gods of Teotihuacán is actually a continuum of masks, so the complete system comprised of the totality of these god-masks is also a continuum as one god shades into another, creating the "secondary" masks we discuss below. This shading is accomplished in a variety of ways in the religious art of Mesoamerica, all of them involving the varying of symbolic details of mask and costume, and the two works of art we are now considering exemplify two of those ways.

The most complex of the two is the mural at Tepantitla. Found on the right half of the east wall of the "Tlalocan" patio, "the most sumptuously painted patio in all of Teotihuacán,"[173] this mural is really two related paintings, one above the other, framed and separated from each other by a highly symbolic decorative border. Restored and reconstructed by Villagra, whose copy of the reconstruction can be seen in the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City (colorplate 3), it is now the most complete one of six such formally similar but probably thematically different pairs that originally decorated the walls of the patio. When one looks at this pair of paintings, it is readily apparent that although the upper and lower paintings are quite different from one another, they are symbolically and visually unified by the images that form a central vertical axis for the composition as a whole.

But a casual glance would find more difference than similarity in them. The upper painting has a large central figure, either a god or an impersonator, wearing a mask and a headdress that displays a bird mask probably representing a quetzal. The figure is depicted frontally either atop or partially obscured by a base or temple platform containing a "mouth" from which streams of water are flowing. From behind the figure, seeming almost to grow from its headdress, rises a treelike form made up of entwined vines or streams of liquid. This central figure is flanked by two priests shown in profile who wear headdresses identical to that worn by the god and from whose hands flow streams of water. Behind the priests, plants, perhaps corn, grow from the streams of water flowing from the mouth in the base in front of or beneath the god. Visually, the "tree," the god, and the base, taken together, dominate the painting so completely that the overall impression is almost that of a painting of a single figure. The lower painting, however, has no such central figure but depicts a large number of small figures seemingly scattered at random over its surface. Although there is a central hill or mountain at the base of the painting containing a symbolic cave or mouth from which two streams of water flow, this painting does not concentrate the viewer's attention but rather diffuses it over the entire painted surface.

Different as the overall effect of the upper and

lower paintings is, a careful look reveals an important visual link between them as the mountain of the lower painting occurs directly underneath the central figure of the upper painting and repeats that figure's triangular form. Although the form of the god is visually more complex than that of the mountain, connecting the small triangle above the eyes of the god's headdress with the edges of the base allows one to realize the figure's essential triangularity. In addition, both the mountain and the god are a bluish gray, and both are depicted on an identical maroon ground. Furthermore, both contain a mouth or cave-shaped form from which flow waters that divide into two streams to form the baselines of their respective paintings. Thus, the repetition of the figure of the god by the upward-thrusting mountain of the lower painting provides a vertical emphasis counteracting the horizontal band created by the frame and bottom line of the upper painting which separates the two.

Strangely enough, however, the band that separates them provides visually the strongest evidence of their thematic connection, for in it, directly between the god of the upper painting and the mountain of the lower, is an image of Tlaloc (colorplate 2b) holding two vases from which flow the streams of water that make up the painting's frame. Virtually identical to the Tetitla Tlaloc, which we have identified as the central image of the god in the art of Teotihuacán, this Tlaloc functions almost as a title indicating the thematic significance of the mural, a theme repeated in the streams of liquid that make up the "tree" and symbolically flow from the hands of the priests in the upper painting and from the cave/mouths of both paintings; in the drops of water falling from the hands of the god and from the branches of the "tree"; and in the fact that the lower painting depicts the paradise of the rain god, the spiritual realm called Tlalocan by the Aztecs.[174]

Taking our cue from that centrally placed Tlaloc mask, when we look again at the vertical axis of the paintings, we see a virtual pillar of masks and mask parts, all of them variations on the theme announced by that central mask. Above the "tree" of the upper painting are two of the many profile views of the central Tlaloc mask which occur in the border framing the pictures.[175] Immediately below the "tree" is the goggle-eyed bird mask displayed in the headdress of the god, and immediately below that is the mask of the god represented by the central figure, a mask quite similar, except for the eyes, to the conventional Tlaloc mask. It is no doubt significant that while the bird mask in the headdress has the goggle eyes generally associated with Tlaloc, the mask of the god does not; or to put it another way, the two masks, taken together, display all of the individual characteristics of the mask of Tlaloc. Below the mask of the god, the mouth in the base in front of or below the god is depicted as an upper lip quite similar to the handlebar mustache upper lip characteristic of some Tlaloc masks, though not the masks of this painting. Directly beneath that mouth is the central image of Tlaloc in the frame, and this image holds two effigy vases that carry identical Tlaloc masks. Below that Tlaloc at the base of the painting is the cave/mouth of the mountain. If we include the two mouths as partial masks, there are nine symbolic masks in the vertical axis of the painting, all of them related in one way or another to the mask of Tlaloc. It is reasonable to conclude from this plethora of masks that Tlaloc provides the theme of the symbolic painting and that the variations on that theme enunciated by the variant masks serve to modify the thematic statement in order to communicate a specific spiritual reality related to the powers generally symbolized by the mask of Tlaloc.

In the light of that obvious thematic centrality of Tlaloc to the mural, it seems strange that the most dominant figure in the mural, the central depiction of the god in the upper painting, is not clearly an image of Tlaloc[176] although possessing some of that god's attributes. The mask worn by the god, like the Tlaloc mask below it but unlike the bird mask in its headdress, has a fanged mouth, ear flares, and eyes in the standard Tlaloc configuration. The Tlaloc theme is also suggested by the bifurcated tongue-like form representing streams of water which descends from the mouth—Tlaloc's serpentine tongue modified to harmonize with the numerous other representations of flowing water in the mural. These streams, like the ones below them in this painting and in the frame, contain starfish forms that, along with other representations of marine life, are linked elsewhere in the art of Teotihuacán to Tlaloc. The shape of the mouth of this mask is also related to other Tlaloc masks, but unlike the Tlaloc in the frame below whose mouth has an upper lip turned under the outer fangs, this mask has a variant of the handlebar mustache upper lip, a stylized version almost identical in shape to that worn by the Tlaloc on the last of the merlons we discussed above (pl. 18), but quite different from the mouth below it in the base. Slightly above the mouth on either side of the mask are the typical Tlaloc ear flares, each composed of two concentric circles.

But with the ear flares, the symbolic features that constitute the Tlaloc theme end. Slightly above these ear flares and directly over the mouth are a pair of eyes quite different from the goggle eyes of the typical Tlaloc mask. Somewhat smaller than Tlaloc's, these have circles representing the eyes framed by "concentric" diamonds on a horizontal band interspersed with vertical lines, giving the effect of a bar across the upper portion of the face rather than the twin circle image associated with Tlaloc. While this eye band is not at all typi-

cal of the Tlaloc mask, it is, as Séjourné points out, commonly seen as the decorative band on the braziers carried on the heads of images of the old fire god (pl. 19), known among the Aztecs as Huehuetéotl or Xiuhtecuhtli. Transplanted to the mask of Tlaloc, its purpose is clearly to link the attributes of that god to Tlaloc, a linkage supported by a number of other references to fire in the mural. The god wears what seems to be a "large yellow (fire-colored) wig"[177] and above that wig a headdress displaying a goggle-eyed bird mask also probably related to fire since an almost identical mask in four representations adorns an incensario found at La Ventilla which was no doubt used, as such incensarios typically were, to burn copal or other incense as an offering to the gods. And this bird mask is quite similar to the masks depicted both frontally and in profile on the columns of the Quetzalpapálotl Palace[178] whose relationship to the butterfly suggests a fundamental symbolic connection with fire. Thus, the masks in the upper painting seem to have as their primary purpose the connection of Tlaloc to Huehuetéotl and the unification of the seemingly opposed forces of fire and water.

That symbolic connection in the upper painting is particularly intriguing because the lower painting makes the same symbolic connection in an entirely different way. As we will demonstrate in our discussion in Part II of the relationship between the Mesoamerican perception of spatial order and the central metaphor of the mask, the cave/mountain image of the lower painting refers specifically to the cave underneath the nearby Pyramid of the Sun, a cave of enormous symbolic significance and almost certainly the scene of ritual reenactments of the coming of the rains. According to René Millon, "offerings of iridescent shell surrounded by an enormous quantity of tiny fish bones" were found in fire pits near the center of the cave, and the fires in which the fish and shell were burned as offerings were, "together with water made to flow artificially, the most essential part of" the cave's ritual, suggesting in several ways a symbolic "union of fire and water,"[179] precisely, of course, the union achieved in the mask of the upper painting. The common purpose of the two paintings thus is to depict the union of these opposed forces and to refer directly to the ritual through which man celebrated that unity. While the upper painting depicts a stylized ritual scene similar to those depicted in the later codices, many of which show priests wearing symbolic headdresses containing masks alongside a single masked god or god impersonator symbolizing the focal point of the ritual, the lower painting refers directly to the ritual use of the cave lying under the Pyramid of the Sun. It is fascinating to realize that the upper scene may well depict, relatively realistically, the ritual preceding the coming of the rains actually enacted at the mouth of that cave so long ago.

Pl. 19.

Huehuetéotl, stone brazier, Teotihuacán

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

It seems clear, then, that both paintings refer to the symbolic and ritual union of fire and water depicted metaphorically in the mask of the central figure of the upper painting. Séjourné suggests its meaning:

The dynamics of the union of two opposites is at the basis of all creation, spiritual as well as material. The body "buds and flowers" only when the spirit has been through the fire of sacrifice; in the same way the Earth gives fruit only when it is penetrated by solar heat, transmuted by rain. That is to say, the creative element is not either heat or water alone, but a balance between the two.[ 180]

And this union is also suggested by the lightning serpent often held by images of Tlaloc. In later Aztec mythic thought, that serpent was known as Xiuhcóatl and was intimately related to Xiuhtecuhtli, the god of fire. And Xiuhtecuhtli, of course, was the Aztec manifestation of the Teotihuacán fire god on whose brazier the diamond-shaped eyes of the god of the Tepantitla mural are found. Significantly, however, Xiuhtecuhtli was also associated with the calendar. He was "lord of the year" and "the god of the center position in relation to the four cardinal points of the compass,"[181] a position with important calendrical implications as we have suggested above in connection with the Codex Borgia Tlalocs. Thus, the relationship of fire and water in the mask at Tepantitla has metaphoric implications regarding both fertility and

time, and a moment's thought suggests the relationship of those two concepts in the ritual ensuring the regular coming of the rains.

A related symbolic suggestion can be seen in the presence of great numbers of butterflies in both the upper border and the lower painting. In the art of Teotihuacán, "this brilliant insect is fire,"[182] and throughout Mesoamerica fire was the symbol par excellence of transformation. It is therefore no surprise to find symbolic references to butterflies on the incensarios of Teotihuacán or to see butterflies related to Tlaloc, since for the peoples of Mesoamerica it was through the process of transformation that the world of the spirit entered into the contingent world of man, creating and sustaining life as we know it. Metaphorically, Tlaloc became rain, exemplifying the manner in which the gods transformed spirit, that is, themselves, into matter, and fire allowed man to reciprocate by transforming matter into spirit. The fire "dematerialized" the substance of the offering and allowed its essence to return to the realm of spirit from which it came, a process that reversed and thus completed the provision of sustenance for the world of man by the world of the spirit. This ritual burning sent clouds of smoke into the air, reenacting the coming of the rain clouds which would initiate another cycle of the endless process in which life was constantly poised between creation and destruction.

That the relationship between these two concepts is metaphorically expressed most precisely and economically in the construction of the mask of the central figure makes clear the reason for the departure from the conventional mask of Tlaloc by the creators of this mural. The principle underlying the construction of the mask is basically the same as the principle by which the individual masks of Tlaloc are constructed, but in this case, it is used to create a continuum of gods by combining their symbolic features. This mask illustrates the fact that the gods were not seen as precisely defined individual entities but shaded into one another as they reached the "limits" of the particular areas of spiritual concern for which they stood as symbols.

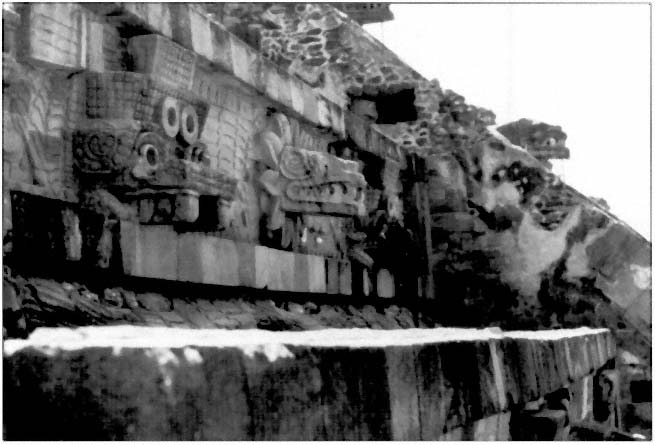

Another significant and quite unusual Tlaloc mask exemplifying the same underlying structural principle indicates that the Tepantitla mural is typical rather than a unique case. This Tlaloc is found on the decorative frieze of the pyramidal Temple of Quetzalcóatl in the centrally located compound the Spanish called the Ciudadela. The frieze (pl. 20), which originally covered the pyramid's surface, is described by Nicholson as "one of the greatest tours de force of monumental stone sculpture in world history." He sees in its "powerful, massive" carving "the essential qualities of the classic Teotihuacán sculptural style."[183] Those superlatives suggest the significance of the frieze, as does the striking thematic unity of its symbolic reliefs, which are divided into six bands, one on each of the pyramid's six levels. Each of these bands has two registers, the lower one on a sloping talud and the upper one on a vertical tablero. Unlike the talud and tablero of the Tepantitla mural, however, these two registers are fundamentally similar as both of them depict the undulating bodies of rattlesnakes. While the talud displays only the snake, on the tablero's undulating serpent are superimposed alternating full-round composite masks of plumed serpents and, strangely in the midst of all of these serpents, Tlalocs. Not only do the composite masks of Tlaloc seem out of place in this serpentine context but their abstract, geometric, "flat" appearance seems designed to call attention to their difference from the naturalistic masks of the plumed serpent which project from the frieze. And, as if to call further attention to the Tlaloc theme, depicted within the sinuous undulations of the serpents' bodies are seashells realistic enough "to permit precise zoological identification."[184]

Although these Tlaloc masks were obviously designed to bring that god immediately to mind, they are quite different from the central image of Tlaloc at Teotihuacán. Viewed frontally, they look like Tlaloc because they present exactly the configuration of shapes found on other masks of the rain god. The upper portion of the mask contains two pairs of concentric circles arranged in the same format as Tlaloc's goggle eyes and ear flares. Below those circles is a projecting horizontal bar, somewhat reminiscent of the highly stylized handlebar mustache upper lip, with two fangs projecting downward from its outer edges. And underneath this projection, on the same plane as the concentric circles, another upper lip appears also in the form of a horizontal bar from which project four curving fangs in a clear variant of the Tlaloc mouth. Obvious as the reference to Tlaloc is, however, the differences between this mask and the typical Tlaloc are equally striking. A second glance reveals, for example, that the "goggle eyes" are not eyes at all. The concentric circles in the position normally assigned to the ear flares are actually the eyes of the mask, and the circles above them which would normally be eyes are merely decorative embellishments placed over the skin of the forehead, the unusual texture of which can be seen within them. The mouth, too, is strange as it is actually two mouths, one superimposed on the other in the manner of a buccal mask. As in the case of the Tepantitla mask, then, we have a Tlaloc modified thematically to contribute to the symbolic statement of a complex work of art.

The point of the modifications is quite clear from a profile view of the Tlaloc mask and even clearer when one includes in that view a profile of the plumed serpent mask next to it (pl. 20) which reveals the striking fact that the eyes and eyebrows of the two masks are quite unusual and virtually identical. Both have an identically shaped round

Pl. 20.

Profile views of Tlaloc and Plumed Serpent heads on the frieze of the facade of the Ciudadela,

Teotihuacán and Plumed Serpent heads lining the stairway.

"goggle" around each eye surmounted by a large, seemingly scaly eyebrow that drops down on the outside of the eye and then sweeps back along the side of the mask to form a spiral. The similarity in the eye treatment allows one to see a similarity in the shapes of the projecting mouths although they are far from identical. In profile, then, these two masks, which seem completely different from one another when viewed from the front, are actually two versions of the same thing,[185] making clear the reason for the change in position of this Tlaloc's eyes. Through the sophisticated manipulation of frontal and profile views, the creator of the frieze was able to connect Tlaloc with the plumed serpent, known in later times as Quetzalcóatl, in order to make a complex symbolic statement that unites those two god-masks to present a larger spiritual reality; the seemingly separate gods must be seen as parts of a continuum, precisely as we saw the gods of the Tepantitla mural, although the symbolic depictions of the relationship are achieved in somewhat different ways in the two works of art. But here Tlaloc's position vis-à-vis the other god is reversed. Despite the obvious importance of Tlaloc at Teotihuacán, the serpent symbolism of the frieze as well as the plumed serpent heads that line the stairway ramps suggest that the rain god here is subordinate to the theme announced by the plumed serpent.

And what is that theme? The most obvious answer is fertility. The undulating serpent bodies, the seashells, and the masks themselves all combine to suggest that the crops that sustain man's life are themselves nourished by the water provided by the gods. In addition to the fundamental fertility associations of Quetzalcóatl and Tlaloc, vegetation is suggested both by the unusual texture of the Tlaloc mask which may well suggest corn, perhaps the reason for H. B. Nicholson's suggestion that it "may be a Teotihuacán version of a Monte Albán maize deity,"[186] and the peculiarly leaflike plumes of the serpent. In addition, a frontal view of the plumed serpent masks emphasizes the fertility-related bifurcated tongue and the jaguarlike pug nose that is depicted as an inversion of the form of the tongue. Emphasized by being framed between these two potent symbols and the front fangs on either side is the circular hole of the mouth. Such a strange emphasis on the mouth opening may well be related to the later Ehécatl, an aspect of the feathered serpent, Quetzalcóatl, who blew the winds that cleared the roads for the coming of the rain through his buccal birdmask. Mythically, Tlaloc and Ehécatl working in tandem provided man's

sustenance, and it is therefore tempting to relate this plumed serpent to that later aspect of Quetzalcóatl. From that point of view, we could see the frieze as symbolically relating two opposed forces, as did the Tepantitla mural, from the union of which comes fertility and human life. Such an interpretation is tempting precisely because it reflects the paradigmatic Mesoamerican conception of the cycle of life.

But there is another symbolic suggestion here as well, for the serpent is also the quintessential Mesoamerican symbol for sacrificial blood, and these two quite different serpent-related masks superimposed on the serpent bodies may well symbolize another unity born of the merging of opposites. Tlaloc as metaphor for the rain and the plumed serpent as metaphor here for sacrificial blood suggest the cyclical process through which life is maintained: in return for the provision of the life-giving rain by the gods, man must provide the sacrificial blood that metaphorically nourishes the gods. It is significant in this regard that atop the pyramid, "a layer of human bones beneath a layer of seashells was discovered,[187] and "shells and numerous vessels representing the water deity," the urns in which the Tlaloc of myth stored the rain, were found in burials at the base of the stairway.[188] Such an interpretation would make sense of the numerous references to fertility in the frieze and to the obvious "double meaning" of the serpents' undulating bodies.

To return for a moment to the mural at Tepantitla, not very far from the Ciudadela, it is interesting to note that despite its utterly different appearance from the Ciudadela frieze, there are remarkable and perhaps significant similarities between them. Séjourné's description of the "frame" of the mural suggests one of them. "This charming image of creation," she says, "is enclosed in a rectangle formed by two serpents intertwined and covered with signs of water and heads of Tlaloc."[189] The intertwined serpents are distinguished from each other by being different colors and thus, for Séjourné, represent different elemental forces. Similarly, the two streams that make up the "tree" rising behind the central figure of the upper painting are different colors and intertwined in such a way as to make obvious the intention to depict a union of opposites. Thus, the mural, in a manner remarkably similar to that of the frieze, depicts fertility flowing from the symbolic merging of opposed elemental forces, and the red color of one of the streams of the tree may well be a reference to the sacrificial blood by which man reciprocates for the gift of the gods.

Such an interpretation of the two works of art would place them both at the liminal meeting point of the realms of spirit and matter, that point in ritual and art where man touches god. In ritual and through art, man is able to function momentarily on the level of god and thus to bring into his world the spiritual essence of life. Significantly, both the placement of the Temple of Quetzalcóatl within the compound of the Ciudadela and the decoration of the pyramid further develop that symbolism of the meeting place of spirit and matter. Situated facing the courtyard of the Ciudadela, the positive upward thrust of the pyramid balances the negative "sunken" space of the court, a balancing repeated in the configuration of the Pyramid of the Moon and its plaza and surely the symbolic equivalent of the combination of cave and pyramid at the nearby Pyramid of the Sun. In each of these cases, the emphasis on the penetration into the upper and lower realms of the spirit defines man's position in the world of nature. As if to emphasize that theme, the stairway that led to the temple divides the face of the pyramid fronting the courtyard. The ramps on either side of that stairway are lined with plumed serpent heads like those on the frieze indicating the dedication of the temple to Quetzalcóatl and prefiguring the symbolic use of serpents to flank temple doorways and pyramid stairways elsewhere at Teotihuacán as well as by the later cultures of the Valley of Mexico. This use of the serpent to define the liminal meeting place of spirit and matter coincides with the serpent symbolism associated with blood sacrifice since it was up these pyramid stairways, after all, that the sacrificial victim made his way to the temple where his spirit was freed by the act of sacrifice to return to its home and his body, now merely matter, released to tumble back down that same stairway to be reunited with the earth.

This symbolic concern with the meeting point of spirit and matter is further indicated by the location of the Temple of Quetzalcóatl within the compound of the Ciudadela, a compound that, as we will show in our discussion of the Mesoamerican perception of the sacred spatial order, stands at the central point of the grid system according to which Teotihuacán was laid out, at the intersection of the main east-west avenue and the Avenue of the Dead, which runs north and south. The Ciudadela thus marks the ultimate union of opposites by defining the center point of the quincunx formed by these two avenues, a quincunx that by its replication of the four-part figure symbolizing the sacred "shape" of space and time defines the ultimately sacred nature of the city. The central point of this quincunx would have been seen as the symbolic center of the universe, the point at which the vertical axis of the world of the spirit, symbolized here by the Via Sacra of the Avenue of the Dead, met the horizontal axis of the natural world, the east-west avenue in this case. That central point naturally would have been, as Millon believes the Ciudadela was, the "sacred setting" for the city's political center, which was, in fact and in the minds of its rulers, the center from which the influence of Teotihuacán radiated to every corner

of the known world. And for the same reason it was "the setting for the celebration of elaborate calendrical rituals" probably led by rulers seen as "the embodiment of the religion of Teotihuacán" since "the Teotihuacán polity was undoubtedly sacralized."[190] The Ciudadela was symbolically the very center, both spiritually and physically, of Teotihuacán.

We must conclude, then, that fertility was not the only issue of this symbolic meeting of man with god. As we might expect from the intimate relationship between the god of rain and the symbolism of rulership in the art of the Olmec "mother culture" as well as in the roughly contemporary Zapotec art of Monte Albán, the Tlaloc masks in this central place suggest the provision by the gods of divinely ordained rulers as well as man's sustenance. It is significant in this regard that the composite masks of Quetzalcóatl as well as those of Tlaloc both have jaguar characteristics as the symbolism of the jaguar was intimately related to rulership by both the Olmecs and the Zapotecs. But both of these masks have serpent characteristics as well, and the serpent, especially the plumed serpent, has strong connections in later Mesoamerican symbolism with rulership, a symbolism often expressed in the metaphoric connection of the serpent and lightning. We saw precisely this relationship in the art of the Zapotecs, and the Tetitla Tlaloc with his lightning spear shaped as an undulating serpent indicates that the same connection was perceived at Teotihuacán. By the time of the Toltecs, in fact, the plumed serpent is thought to have supplanted the jaguar as the symbol of kingship, and Quetzalcóatl's fertility symbolism had been relegated to Ehécatl.

But at Teotihuacán, Tlaloc was still the divine force from which the earthly ruler drew his mandate. Wigberto Jiménez Moreno characterizes what we would also see as the legitimizing role of the Teotihuacán Tlaloc nicely. He sees the ruler's authority as

deriving from the fact that he personified the god of lightning and rain, Tlaloc-Quetzalcóatl. Indeed, one source tells us that Tlaloc was a lord of the quinametin, the "giants" whom I have identified (1945) with the Teotihuacanos. This could be understood to mean that the most venerated god in the Teotihuacán culture was personified by the ruler-priest, who would appear as Tlaloc's living image.[191]

Given the Ciudadela's symbolic identity as the center of the universe and its actual role as the locus of sacralized political power at Teotihuacán, it is to be expected that the art of that compound would symbolize the divine basis of what we today call secular power. And the burials with seashells were probably related to the ritual involving the accession of a new human wielder of that essentially divine power, a man within whom the later Aztecs would say the god would "hide himself." It would be hard to imagine a better metaphor for that relationship than the shells, which had the virtue of suggesting fertility as well.

Ultimately, then, the masks of the frieze of the Temple of Quetzalcóatl symbolize the relationship between the realm of the spirit and the world of man and suggest that life is made possible in this world through the continuous intervention of that other realm. In the final analysis, what is provided is order, the order of civilized life made possible by agricultural fertility and symbolized by and inherent in the ruler; the spatial order derived from the central point "of ontological transition between the supernatural world and the world of men," a point symbolized at Teotihuacán by "the Temple of Quetzalcóatl [which] probably functioned not only as the opening toward the supernatural world of the vertical, but also as the pivot of the horizontal sociopolitical cosmos";[192] and the temporal order symbolized by the compound of the Ciudadela itself. According to Kubler, "the three groups of four secondary platforms surrounding the main pyramid in the principal court recall the calendrical division of the Middle American cycle of fiftytwo years into four parts of thirteen years each,"[193] a division that, according to Seler, is one of the primary concerns of the page on which the Codex Borgia Tlalocs are depicted.[194] In addition, within the boundary marked by these platforms, the courtyard facing the pyramid "was probably used for rituals of a calendrical nature."[195] The calendrical significance of the pyramid itself is suggested by the widely held view that it originally displayed from 360 to 366 composite masks, numbers of clear calendrical significance and a fact that would link it to the Pyramid of the Niches at El Tajín as a calendrically symbolic structure. It is quite significant from our point of view that all of these connections between the Ciudadela and the temporal order find their primary symbol in the composite mask of Tlaloc. As Roman Piña-Chan points out, "this deity can be considered the Lord of Time, of the annual cycle which nourishes vegetation and life, on the basis of the interwoven triangle and rectangle, the symbol of the year, in his headdress."[196]

Thus, it all comes together in the mask. The composite masks of Tlaloc and Quetzalcóatl on the frieze carry in their symbolism all of the meanings elaborated by the other symbols on the frieze and by the compound's structures, ritual use, design, and siting. What Henri Stierlin says of the masks of Tlaloc here can surely be extended to encompass the metaphoric construction of all the masks of the gods by the "learned clerics" of Teotihuacán:

The abstract nature of the representational modes resulted in what can only be called graphic symbols that are replete with significance for those who beheld them. In this sense it was the expression of a sacerdotal body, the

reflection of a caste of learned clerics concerned with elaborating the concepts of a pantheon in which the forces of the universe are personified.[197]

These graphic symbols recorded the speculative thought of that sacerdotal body, "a well-integrated cosmic vision" that Jiménez Moreno has likened in its sophistication to the Summa of Saint Thomas, expressing "a religious doctrine and a very coherent and harmonious philosophy [capable of] fostering the architectural, sculptural, and pictorial creations."[198] And as we have seen, the mask, especially the mask of the rain god we call Tlaloc, served as the central symbol in the elaboration and expression of that profound body of spiritual thought.

We do not know the name of Teotihuacán's Saint Thomas or, more appropriately, Aristotle or Plato, nor even the language he spoke, but the evidence compels us to acknowledge the existence of such seminal thinkers there and allows us to savor the subtlety and originality of the small portion of their thought we are able to know. The evidence we have examined here, the complex multivocality of the symbolic mask of Tlaloc, is clearly but a small part of the profound body of thought characteristic of that highly developed society, which

was unquestionably the preeminent ritual center of its time in Mesoamerica. It seems to have been the most important center of trade and to have had the most important marketplace. It was the largest and most highly differentiated craft center. In size, numbers, and density, it was the greatest urban center and perhaps the most complexly stratified society of its time in Mesoamerica. It was the seat of an increasingly powerful state that appears to have extended its domination over wider and wider areas. . . . Indeed, it appears to have been the most highly urbanized center of its time in the New World.[199]