Thelma & Louise as Screwball Comedy

Peter N. Chumo II

The elements are familiar: the killing, the robbery, the flight from the police, the high-speed car chase. It is little wonder that many critics see Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise as an outlaw film. However, it also displays key elements of a screwball comedy, of which the "road screwball" is an important subgenre (best exemplified by It Happened One Night , 1934) whose themes include

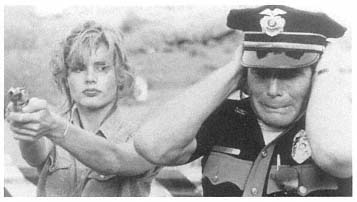

Role reversal: Jason Beghe as the state trooper

escaping the constraints of authority for the freedom of the open road, playing out different roles, and ultimately shedding one's old identity for a new one.

While outlaw films like Bonnie and Clyde and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid have scenes of deadpan humor, these moments generally do not suggest the self-awareness or growth typical of the smart, witty screwball heroine. In Thelma & Louise , however, when J.D. suggests that Thelma's husband is an "asshole," and Thelma agrees, "He is an asshole. Most of the time I just let it slide," we see a classic screwball heroine assuming a certain control over her life while also maintaining a sense of irony toward her childish husband.

Liberation and growth through role-playing—distinctive features of the screwball tradition—figure prominently in Thelma & Louise , especially in Thelma's robbery of the market, her personal turning point when she casts aside all inhibitions, takes on the persona of an outlaw, and gains a new sense of freedom. She uses the theatrical "robbery speech" that J.D. has taught her, but does not become a copy of a male outlaw. Rather, she makes the role her own and adjusts the robbery to suit her own tastes when she asks for a couple of bottles of Wild Turkey, which has become her favorite drink on the road. Thelma, then, sheds her identity as a timid, even childlike housewife by relying on her own instincts and creativity within the outlaw role. Although Thelma's crime initially shocks Louise, she soon gets caught up in the fun, and their laughter and sense of exhilaration as they drive away from "the scene of our last goddamn crime!" (as Louise enthusiastically puts it) solidifies them as a screwball couple having fun with their outlaw personae, goofing off on the road, and taking control of their lives in the process.

In the encounter with the state trooper, a wisecrack defuses a potentially violent moment as Thelma, holding a gun on the officer as he explains that he has a wife and kids, advises him, "You be sweet to 'em, especially your wife. My husband wasn't sweet to me. Look how I turned out"—the smart, sassy lines of a screwball heroine who has a sense of humor about her situation. Instead of a disturbing confrontation, we have a prank (they lock the officer in his trunk) and sharp, funny dialogue, more akin to the fun of a screwball couple defying authority (perhaps Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby ) than outlaws at odds with society in general.

While Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis have entered the pantheon of great screwball couples, their sense of freedom poses a generic problem, since the screwball couple normally achieve a clarity of vision that enables them to be reintegrated into society. As a female screwball couple who have no desire to return to their old lives and are actually being hunted by male society, Thelma and Louise cannot follow this pattern, but the film itself finds a way of going beyond the usual screwball marriage. Finally surrounded by police and choosing to drive over the edge of the Grand Canyon rather than be captured, Thelma and Louise first kiss and then clasp hands in a mystical marriage that distinguishes the film as the most unique screwball ever made—not simply because it presents a marriage of females but because it is a transcendent, not a social, marriage and ultimately an apotheosis, a mythic flight into forever.