3—

The Concept of Urban Catalysts

As we argued in the preceding chapter, the changing stances in European urban design theory in the past few decades have offered inadequate guidance for American cities. In particular, existing urban design theories do not indicate how to achieve the goals associated with them in an American context. Perhaps because of their origins, most of the theories seem to assume a central government with the political and economic power to implement the development envisioned. In the United States such an assumption is not justified except when federal programs like urban renewal or Operation Breakthrough or the Interstate Highway System or urban homesteading appear. But federal programs cannot be counted on to support urban design efforts consistently and should not form the basis of urban design theory for America. At most, the urban designer can use federal programs occasionally, at particular times and in specific situations.

American designers and developers have often tried to implement aspects of these European visions by using American political and financing tools, including tax increment financing (the tax on increased land value), municipal write-offs of land acquisition costs, tax deferrals, tax abatements, mortgage guarantees, profit sharing, incentive zoning, and so forth. Nonetheless, American urban design typically lacks appropriate, American, visions of cities. In short, European theories offer ideals of limited applicability and few tools for implementing them. Pragmatic America offers a changing set of tools but no theory appropriate for America. We need a different way of looking at the problem of reconstituting America's center cities, a different vision.

We do not argue with existing European-based concepts; in fact, we recommend, pragmatically, adopting many European urban values. But note: it is the values , not the forms associated with them, that we commend. The following values derived from European cities and European-based urban design theories constitute the givens of good urbanism, not only in Europe but in America:

1. Mixed activities are basic to cities.

2. Buildings (and the spaces they form) are the natural increments of urban growth.

3. New urban growth must recognize the context provided by past construction.

4. A major goal of urban design is the shaping of public open space, including meaningful street space.

5. Streets must accommodate various forms of transit and enhance pedestrian activity and movement.

6. Transportation systems should be rational.

7. Urban places should be varied to enhance the activities associated with them: housing, neighborhood shopping, major retail, civic, and so forth.

8. Citizens should have a role in shaping urban settings.

But even as we commend the values, we diverge sharply from the tenets of both European idealism and American pragmatism in considering how to implement urban design ideas. We suggest that urban design for center cities, instead of being conceived as the process of implementing one or another ideal image of the city, using various available tools, is more appropriately thought of as a process of arranging catalytic reactions. There should be no ultimate vision for the urban center, either functionalist, humanist, systemic, or formalist. And a tool box of implementation techniques should not simply be left open for use anywhere at any time. Rather, there should be a sequence of limited, achievable visions, each with the power to kindle and condition other achievable visions. This would be urban catalysis. Visions for the new urban center should be modest and incremental, but their impact should be substantial, in contrast to the large visions that have been the rule, with their minimal or catastrophic impact.

The metaphors guiding urban design theory to date have been inadequate. Organismic and mechanical metaphors ("heart of the city," "the city is a tree—or semilattice," "organism," "mechanism") are of limited use as guides to architectural and urban design decisions. We find the chemical/catalytic analogy to be more useful and versatile. An urban catalyst might be a hotel in one city, a shopping complex in another, a transportation hub in a third. It could be a museum or theater. It could be a designed open space or, at the smallest scale, a special feature like a colonnade or a fountain.

An urban catalyst has a greater purpose than to solve a functional problem, or create an investment, or provide an amenity. A catalyst is an urban element that is shaped by the city (its "laboratory" setting) and then, in turn, shapes its context. Its purpose is the incremental, continuous regeneration of the urban fabric. The important point is that the catalyst is not a single end product but an element that impels and guides subsequent development.

Urban catalysts are dynamic; they act and have effects. In contrast, functionalist architecture may be conceived as a physical model for cities; humanist design, as a stimulating setting for human activities; systemic design, as a network of communication; and formalist design, as an

embodiment of urban archetypes. Each one has a limited scope and vision. Each suggests that cities should have a single underlying nature. By contrast, urban catalysts are capable of molding a city in any of several ways, none of them dictated by a single-minded vision.

Though the metaphorical use of the word catalyst is widespread in urban design and planning literature, the concept of urban catalysis has value beyond the suggestiveness of the metaphor; in fact there is an analogy between the chemical process of catalysis and mechanisms of successful urban design and urbanism. Often those who talk about catalysts refer to vast developments—Gruen's Fort Worth Plan and Pei's Boston Government Center plan were intended as catalysts; but we propose that urban catalysts are better thought of as smaller elements—a building, a fragment of a building, a complex of buildings, or even a report or set of guidelines. Although renewal and revitalization schemes for cities are often touted as catalysts, many of these schemes remain inert and have little impact. They do not cause the promised urban reactive change. Sometimes the term catalyst refers to economic processes, typically an infusion of funds that leads to other infusions of funds, or, at a gross scale, it means that one development makes additional developmental projects look like good investment risks. Mere change, however, just adding development to development, does not assure good design or rewarding urbanism, nor do mere investments in redevelopment, as countless renewal schemes demonstrate.

The subtleties of the catalytic concept and its power to help us understand the interaction of urban design and other factors are usually overlooked. Architecture, too, is catalytic. Not only infusions of capital that incidentally produce new buildings and reconstructed streets but buildings themselves can be catalysts, ensuring the high quality of urban redevelopment. Urban design quality is determined at the scale of buildings, not balance sheets.

Catalysis involves the introduction of one ingredient to modify others. In the process, the catalyst sometimes remains intact and sometimes is itself modified. Adapted to describe the urban design process, catalysis may be characterized as follows:

1. The introduction of a new element (the catalyst) causes a reaction that modifies existing elements in an area. Although most often thought of as economic (investments beget investments), catalysts can also be social, legal, political, or—and this is our point—architectural. The potential of a building to influence other buildings, to lead urban design, is enormous.

2. Existing urban elements of value are enhanced or transformed in positive ways. The new need not obliterate or devalue the old but can redeem it.

3. The catalytic reaction is contained; it does not damage its context. To unleash a force is not enough. Its impact must be channeled.

4. To ensure a positive, desired, predictable catalytic reaction, the ingredients must be considered, understood, and accepted. (Note the para-

dox: a comprehensive understanding is needed to produce a good limited effect.) Cities differ; urban design cannot assume uniformity.

5. The chemistry of all catalytic reactions is not predetermined; no single formula can be specified for all circumstances.

6. Catalytic design is strategic. Change occurs not from simple intervention but through careful calculation to influence future urban form step by step. (Again, a paradox: no one recipe for successful urban catalysis exists, yet each catalytic reaction needs a strategic recipe.)

7. A product better than the sum of the ingredients is the goal of each catalytic reaction. Instead of a city of isolated pieces, imagine a city of wholes.

8. The catalyst need not be consumed in the process but can remain identifiable. Its identity need not be sacrificed when it becomes part of a larger whole. The persistence of individual identities—many owners, occupants, and architects—enriches the city.

Existing theories specify desirable but narrow ends: a meaningful public realm; or efficient and coherent organization; or personal, experiential, gratification. They do not indicate either how these ends can be achieved or that all of them have merit. At best, implementation is described in generalities: citizen participation, collective (rather than individual) investment, poetic transformation, administrative fiat, and so forth.

A catalytic theory of urban design is not an alternative to existing theories but subsumes them, accepting what they have to offer. What it does that existing theories fail to do satisfactorily is describe how to get from

29.

Diagrammatic representation of the catalytic process. Actions (represented by

hatching), whether developments, restorations, reports, or whatever, catalyze

other actions, which in turn lend impetus to others. Each action is constrained

too, so that the reaction does not destroy the city. The moderating aspect of the

process is represented by the broken lines around the hatching.

goals to implementation. Action and reaction, cause and effect are integral to the catalytic concept.

Catalytic theory does not prescribe a single mechanism of implementation, a final form, or a preferred visual character for all urban areas. Rather, it prescribes an essential feature for urban developments: the power to kindle other action. The focus is the interaction of new and existing elements and their impact on future urban form, not the approximation of a preordained physical ideal.

To explain the concept of urban catalysis in more concrete terms, we look at events in Milwaukee's downtown, in particular, the impact of a new setting for retail activity called the Grand Avenue. Milwaukee is an appropriate case study because its downtown had been declining for more than a decade. The urban center was not just inert but entropic, having dropped to fourteenth among the fourteen shopping centers in the region. The Grand Avenue quickly became the region's prime retail center, and both downtown itself and attitudes about downtown changed dramatically. The changes are not the by-product of new stimuli; there are no new factories, no mammoth construction projects, no growth industries pumping money into the local economy. Instead, the changes are the product of thoughtful strategic planning and a commitment to design quality. After this chapter looks in detail at catalytic events in Milwaukee, examples of the catalytic urban design process in other cities are discussed in chapter 4.

Until 1973, the revitalization of downtown Milwaukee was little more than sputterings, false starts, isolated and improbable visions, and a broad conviction that "it can't happen here." Land was cleared for a functionalist urban enclave (Juneau Village), only one-third of which was built. A downtown freeway loop, begun but never finished, did not satisfy the desirable (systemic) objective of linking a series of parking structures to freeways. A civic axis, inaugurated with the design for the County Courthouse, dissipated almost immediately. Incidental historic reclamations were undertaken, but they did not exert a potent influence on other developments; as a result, there was little sense of historical downtown Milwaukee. New highrise office structures rose, conceived, however, not as integral parts of a revived downtown but as objects on private plazas/podiums.

Warnings that downtown was dying had gone out as early as 1957, when Milwaukee's Board of Public Land Commissioners declared that "the vitality of the central district is threatened," and everyone believed them. What was wrong in Milwaukee was, first, attitude, a lack of will to make things happen; second, isolated rather than integrated redevelopment—revitalization efforts lacked coordinated direction; third, the absence of effective centralized power. City Hall could not revitalize the city, nor could individual corporations.

To turn Milwaukee around required a combination of corporate commitment to the city (above and beyond immediate corporate profits) and a political structure willing to support this private initiative in a variety of ways. This is not to say that corporate Milwaukee took control; rather, it

provided the focused economic and political means that could become a driving force for redevelopment. Years of miscellaneous federal, municipal, and private investment had failed to reverse the decline of the center city. Such a reversal required "a more comprehensive and continuous approach to new development—a leveraging of public and private investment in synergistic efforts." The use of corporate funds at such a scale in the traditionally public realm of development planning was new and, as is so often argued, brought a needed sense of businessmindedness. "Corporate funding of planning replaces some municipal funds . . . , but it does not usurp public responsibility or involvement."[1] A partnership of public and private interests is built.

The story of catalytic redevelopment in Milwaukee begins with a 1973 study commissioned by the Greater Milwaukee Committee. It offered a vision for a new downtown, which in turn could change attitudes. The Chicago office of Skidmore Owings and Merrill prepared the report, called "Milwaukee Central Area Study." It recommended the formation of a development corporation and the creation of a retail core with related uses.

Catalytic processes in Milwaukee began when the SOM study aroused corporate and municipal interest. This combination had the potential to attract a third element, a developer, the Rouse Company, to manage the process. According to a Rouse representative, "What we look for in rebuilding is a once vibrant area with a strong current business and civic commitment to improvement." Milwaukee now had that.[2]

When it became clear that risk capital would be needed for renewal to occur in downtown Milwaukee, the Milwaukee Redevelopment Corporation (MRC) was created. Its first, crucial, project was to remold and reshape the image of downtown. The vehicle would be an innovative center city shopping complex incorporating the best features of suburban shopping complexes with the vitality and richness of an urban center.

The Milwaukee Redevelopment Corporation then took three steps. First, it proposed the construction of a retail complex called the Grand Avenue, which would both recall Grand Avenue, Milwaukee's historical retail/commercial artery (now Wisconsin Avenue), and offer an interior place, a semipublic realm better than that found in any suburban shopping center. Second, the MRC listened and responded to reactions to the idea. Third, it became a leading partner in the development and a link between private and public interests and investments in the project.

What is the secret of the Grand Avenue's success? "A bold vision, the money to turn a vision into reality, and the willingness of government and business leaders to work toward a common goal are important ingredients." From the point of view of former MRC Executive Director Stephen Dragos, "What ultimately made the Grand Avenue more than just an architect's sketch was the muscle provided by city and business leaders. That they recognized the need for such a venture and believed in it enough to gain widespread support made the Grand Avenue a reality."[3] Henry Maier, for example, the city's mayor, and Francis Ferguson, head of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company, "moved heaven and

30.

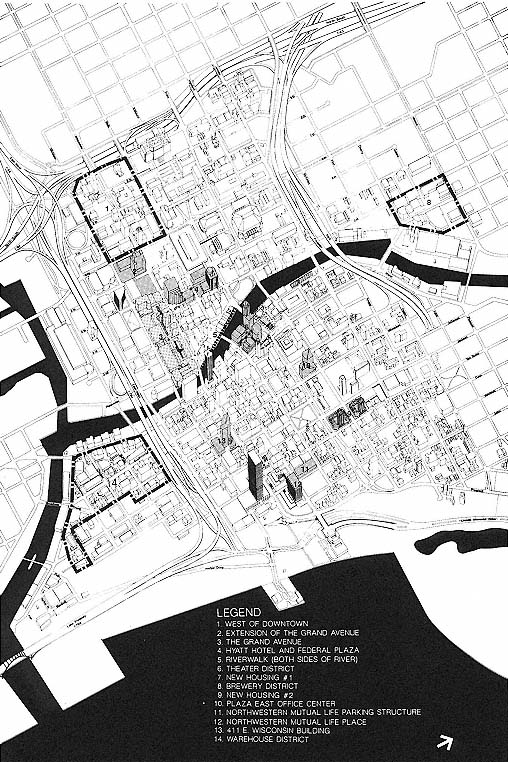

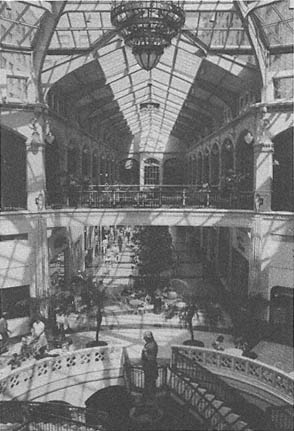

The Grand Avenue, Milwaukee. After a study in 1970 indicated that Milwaukee

needed risk capital for renewal, the Milwaukee Redevelopment Corporation (MRC)

was formed in 1973 as a limited-profit, blue-chip grouping of large firms.

Conceived by the MRC and the city in1976, the Grand Avenue concept was

reviewed in 1977, and negotiations with a developer, the Rouse Company, began in

1978. Private investment amounted to $18 million, with the Rouse Company

contributing $19.5 million. The $39-million investment of the city of Milwaukee took

the form of an Urban Development Action Grant and a tax-increment bond issue. No

new tax dollars were involved.

a.

Aerial view, looking south, shows how the Grand Avenue links

the two existing department stores at either end and incorporates

the existing Plankinton Arcade building. The tall buildings above

Boston Store in this view predate the construction

of the Grand Avenue.

b.

The scale of the Grand Avenue development is evident in this plan of

downtown Milwaukee.

c.

This section through the Grand Avenue looks north, showing the department stores anchoring

each end and the two major interior spaces—a new one (left) and the existing Plankinton Arcade.

31.

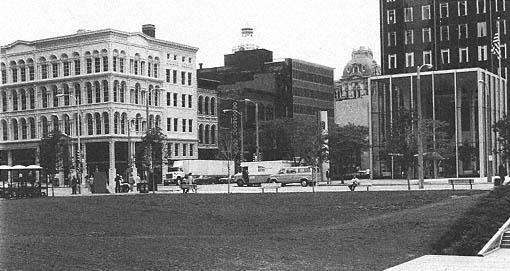

Downtown Milwaukee, showing the Grand Avenue and the location of other developments

that it has influenced.

earth to make it happen. Public officials and corporate leaders worked long hours to make The Grand Avenue the best it could be with the threat of failure looming over their labors. People put their careers on the line to support a project that conventional wisdom said first couldn't happen, and second would be a flop if it did happen."[4]

From the point of view of catalytic urban design, the success of the Grand Avenue goes far beyond the bold vision, money, and political muscle that brought it into being. The value of the Grand Avenue is only partly itself; it is equally valuable for its subsequent effects, the way it was able to catalyze other development. The section that follows analyzes this catalysis.

1—

The New Element Modifies the Elements around It

Hyatt Hotel and Federal Plaza

Even before the Grand Avenue was built, it began to have side effects. Agreements to erect a new hotel and a federal office building nearby were obtained from third parties, along with support for these efforts from the city. Thus the catalyst begins to structure a receptive environment even before it takes physical shape. Although it might appear that the hotel and federal building caused the Grand Avenue, the opposite is closer to the truth.

Skywalk System

One of the early by-products of this interaction between the Grand Avenue, the Federal Building, and the Hyatt Hotel was a skywalk system, a second-level pedestrian network to link these elements with an existing convention center and, ultimately, other parts of downtown. The system has already been extended east across the Milwaukee River, and further extensions are planned: west to the Marc Plaza Hotel and possibly east beyond the Marine Bank Building.

East Town

Some critics of the Grand Avenue development had predicted that the area east of the Milwaukee River, called East Town, would suffer from the new commercial attraction to the west. A view of the world that assumes a finite number of shoppers with a finite amount of disposable income would have to draw such a conclusion. But catalysts, while recognizing and respecting natural limits, can unleash and coalesce energy and attract interest that is not otherwise apparent in the field. For example, the Grand Avenue has attracted custom from broader realms. Whereas downtown had been deserted on weekends, suddenly it was attracting sixty thousand people during those two days, and twenty to twenty-five thousand every weekday.[5] So instead of robbing East Town of custom, it has brought more shoppers. East Town merchants acknowledge that there has been a spillover effect; their East Town Association reported "constant sales increases month after month" after the Grand Avenue opened.[6]

32.

The emerging skywalk system. All except the extension 0to the Marc Plaza Hotel has

been built.

Riverwalk

Bridging the Milwaukee River with a skywalk to East Town not only made a symbolic and practical connection but also gave impetus to a long-standing dream of turning the Milwaukee River into an urban amenity. Earlier, incidental, efforts to address the possibilities of the river now could be linked because of a real commitment, a belief in the value and the plausibility of a riverwalk system. Design specifications for it have been written.

Apart from serving as an amenity, a riverwalk will bridge a conceptual gap between commercial Milwaukee, as represented by Wisconsin Avenue businesses, and cultural Milwaukee, represented by the Performing Arts Center on the river several blocks to the north. A riverwalk system will link these and, more important, will provide support for another byproduct of downtown rejuvenation: a theater district.

Theater District

For several years the Milwaukee Repertory Theater had been searching for a space of its own, designed for its needs. Among its options was an unused power plant on the river halfway between Wisconsin Avenue and the Performing Arts Center. The lively new configuration of downtown represented in the Grand Avenue not only made the power plant location reasonable but also unleashed a slightly grander vision of a theater complex and activity node that would be a focus for the offerings of the Milwaukee Repertory Theater as well as those of the adjacent historic Pabst Theater and Performing Arts Center. The Grand Avenue thus gave the shot of confidence needed to spur investment in a mixed-use development associated with the theater district.[7] The focus of the new theater district is an arcadelike space supported economically by residential, office, and retail uses. Called Milwaukee Center, this node is conceived as a way of increasing and enhancing nightlife downtown, thus strengthening and supporting the Grand Avenue's shopping and service activities.

Extension of the Grand Avenue

The effects of the Grand Avenue are also being felt to the west. The Grand Avenue is expected to generate its own extension by enveloping an additional city block and by making an important skywalk connection to the Marc Plaza Hotel (shown in Figure 32).

West of Downtown

Further west, interest has been kindled in improving the connection between downtown and the area around Marquette University, now separated by the expressway. Discussions have been held and plans proposed to bridge this gulf. The Grand Avenue has proved that downtown can be attractive, thus giving impetus and reassurance to those who wish to upgrade this transitional area to the west.

Warehouse District

Even before the completion of the Grand Avenue, an area of underutilized loft buildings, warehouses, and produce markets to the south had been talked about as an asset to the city. Cer-

33.

Proposed Milwaukee Center, part of the new theater district

(City Hall to the right, Performing Arts Center above).

tainly, similar areas in other cities have been transformed and made economically viable. But until the Grand Avenue catalyzed a new "can-do" attitude, no real progress was made. The Third Ward warehouse district is now, however, experiencing a renaissance.

New Housing

Further afield, the impact of the Grand Avenue and related developments has inspired confidence that housing downtown will be desired if downtown itself is desirable. A townhouse development on the river has appeared, and land belonging to the Juneau Village urban renewal project that had remained vacant since the 1960s has become the site of middle- and upper-income housing. Called Yankee Hill, this project is a joint venture of the Milwaukee Redevelopment Corporation and a private developer, Madsen, the first to follow the Grand Avenue.

Brewery District

North of downtown, plans are under way to adapt for reuse two former breweries, one of which had been lying idle for years. An earlier concept for its adaptive reuse (Figure 123) was revised and implemented.

Although one way of characterizing the catalytic process in Milwaukee is to identify the physical increments of revitalization and transformation, the developments themselves, it is equally important to recognize the transformation in attitude that the Grand Avenue has engendered:

34.

New housing along the east bank of the Milwaukee River, designed by

William Wenzler Associates, architects (City Hall in background).

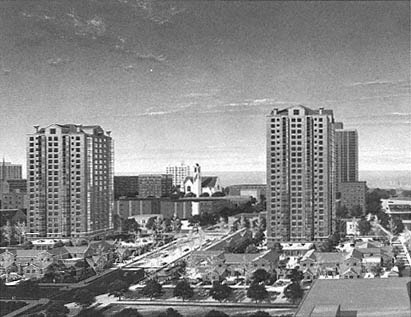

35.

Yankee Hill housing. Forty-four townhouses and two housing towers, designed

by Kahler Slater Torphy Engberg, architects. This joint venture by the Madsen

Corporation and the Milwaukee Redevelopment Corporation followed the MRC's

success with the Grand Avenue.

36.

Cartoon by Brian Duffy celebrating the Grand Avenue, published in

Milwaukee Magazine, November 1982.

I can't say that nothing would have happened downtown if the Grand Avenue hadn't happened—that's not true. But I don't know if people would have been as bullish about the redevelopment potential of the central city. I can tell you that the attitude in Milwaukee has changed from "The downtown is dead" to "Anything is possible and we can probably make it happen."[8]

According to John Wellhoefer, Dragos's successor at the MRC, "the success of the Grand Avenue meant a complete 180-degree turn in the sentiment about investing in Downtown Milwaukee. It used to be okay to work Downtown. Now it's a place people want to go to see and be seen."[9]

For Edmund Bacon, commenting on the transformation of downtown Milwaukee, "The real driving force of making a city become vibrant, alive and economically feasible rests in establishing in the collective mind of the people what the city can become."[10] The Grand Avenue and the chain reaction it has unleashed have created a situation in which "people want a renaissance of downtown to happen. . . . Today the general opinion is that downtown redevelopment should continue bigger and better, and that virtually anything is possible if we put our collective minds to it."[11]

All of the visions that accompany this flush of civic enthusiasm cannot be accommodated. Not everything can happen. What is important is that suddenly some dreams that had been thought unrealistic seem possible.

2—

Existing Elements Are Enhanced or Transformed in Positive Ways

This principle is manifested in two ways, in buildings and in people's behavior. In the case of the Grand Avenue, the Plankinton Arcade, which had withered in both its role and its physical condition, was refurbished and given a new life as the centerpiece of the Grand Avenue development. Previously remote from the action of Wisconsin Avenue, the arcade is now the skylit crossroads of the complex. Behavioral patterns have changed, too. Downtown in Milwaukee traditionally had meant retailing, but the range of retail activity had declined with the appearance of suburban shopping centers. In less than two years following the development of the Grand Avenue, downtown was once again the prime center in the Milwaukee retail market.

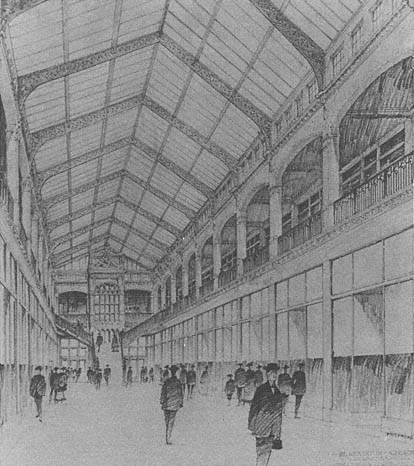

37.

Original design drawing for the long interior space of the Plankinton Arcade.

Holabird and Roche, architects, 1916.

Restoration and preservation need no justification; their utility and economic sense are proven. It is instructive, however, to identify the range of attitudes that characterized even this one revitalization project.

Restoration

The Plankinton Arcade had an architectural character and a physical organization that suited the concept for the Grand Avenue; in fact, with its interior circulation spine, it established the pattern for the whole complex. The arcade had been unsympathetically modified; it needed only to be restored.

38.

New construction respects and incorporates existing buildings.

Modification

Buildings in the block west of the Plankinton Arcade had a conventional orientation to the street and turned their backs to the service alley to the rear. Here the task was to give these buildings a dual orientation without compromising their architectural character or functional utility. The Woolworth Building required the most extensive changes. The two existing department stores needed only to add interior aisles to connect with the skywalks.

It would be misleading to suggest that nothing is destroyed in a catalytic process. At the Grand Avenue, the old (but unexceptional) Plankinton Hotel had to make way for a needed parking structure. Other, minor, commercial and office structures were also destroyed. But landmark buildings like Gimbels (now Marshall Field), the Plankinton Arcade, and Boston Store remained. The commercial flavor of Wisconsin Avenue was retained. The key to enhancing and transforming rather than destroying the context is to formulate a plan that retains and improves places characterized by good architectural and urban design; often such a plan requires a patchwork approach to development, one that incorporates existing buildings instead of cleaning the urban slate.

Sometimes social costs are associated with large developments like the Grand Avenue, but this was not the case in Milwaukee, since there was little housing in the area being developed. And, if anything, the improvements seem to have created jobs.

3—

The Catalytic Reaction Does Not Damage Its Context

Milwaukee's Wisconsin Avenue was a typical linear shopping street with surprisingly little retailing depth, in most cases no more than half a block. This configuration required long walks between shops, often in bad weather. To compete with the comfort and compact form of suburban shopping malls, shopping in a revitalized downtown would need to be consolidated and shoppers sheltered, without spurning the rest of downtown in the process.

The configuration of the Grand Avenue achieves these aims by opening many ground-floor shops to both the street and the interior concourse. Thus the Grand Avenue creates a focus adjacent to Wisconsin Avenue without destroying the traditional character of the avenue in the process.

Although they are not a characteristic of all urban catalysts, the benign edges of the Grand Avenue moderate its impact on its context. Its end points, Boston Store and Marshall Field, and most of its frontage on Wisconsin Avenue remain as they were before. The project does not extensively inject new forms; it does not dramatically disrupt downtown's established architectural character. Instead, the Grand Avenue adds space and form within the existing pattern of the city. It is noteworthy that a radical reorganization of pedestrian space could be accomplished without radically affecting the architectural character of downtown.

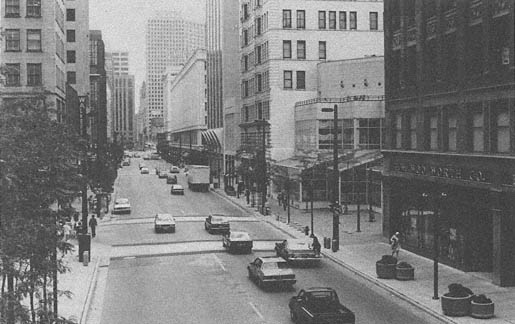

39.

The context of the Grand Avenue before construction (looking west).

40.

The context of the Grand Avenue after construction (looking east). The new Grand Avenue

entrance—the only new frontage on Wisconsin Avenue—occupies a section of North Third

Street (east of the Woolworth store).

Admittedly, many revitalization projects do not begin with buildings in place that remain useful and have strong architectural character—like the Plankinton Arcade and the Marshall Field store. In those projects it is not possible to leave what exists as benign edges. Nevertheless, whatever edges remain can still have an important impact, for a building or a development offers cues to what could or should follow from it on adjacent sites. Existing parking structures along Michigan Avenue, one block south, seemed to suggest that street as a site for the Grand Avenue's parking needs. Creating a major pedestrian entrance where Third Street was closed suggested a public space node there—and the design of the Federal Building responded by creating Federal Plaza. Skywalks connecting segments of the Grand Avenue suggested skywalks to extend the web of connections beyond the shopping complex. Such design cues are an important part of the catalytic process.

The responsibility for containing side effects lies not with the architects of development A but with the developers, owners, architects, and municipal overseers of subsequent developments B, C, D, and so forth. Although there is an inclination to capitalize on increased land values created by a catalyst, it is important to use the new resource imaginatively and with restraint. An excellent example of such imaginative restraint is the refurbishment of the Iron Block building a block from the Grand Avenue. The city's only remaining commercial building with a cast-iron facade, it had been left to decline. Given its corner location on Wisconsin Avenue and its proximity to the new catalyst, the Iron Block site might have been exploited. But instead a thoughtful reclamation has taken place—evidence of laudable restraint that improves the quality of downtown without sacrificing an owner's opportunity to profit from the turn of events.

4—

A Positive Catalytic Reaction Requires an Understanding of the Context

Architectural and Urban Character

There is a tendency to think of retail design in relation to suburban precedents; urban architecture, however, should be more sensitive than this. The revitalization of downtown requires architecture appropriate to the downtown, not contrived atmosphere or generic design. "There's no rationale behind a suburban transplant in the central city," says Stephen Dragos. "It won't work." To compete successfully and attract additional investment, a downtown center "has to be something that uplifts the spirit, that's superior to everything else in the surrounding area. That was our objective, so we had to get the best."[12]

The architecture of the historical center city can be differentiated from that of the suburbs through historicizing motifs. But too often these motifs are no more than pastiche. A more sympathetic response to historical architecture can be achieved by understanding its principles. For example, in the Grand Avenue the shape of the cross section is tighter

41.

Iron Block, built in 1860 (refurbished in 1984).

George H. Johnson, architect.

42.

Interior of the Plankinton Arcade, whose refurbishment

was part of the Grand Avenue development.

Refurbishment architects: ELS / Elbasani and Logan, 1983.

43.

Arcade in a new portion of the Grand Avenue.

ELS / Elbasani and Logan, architects, 1983.

and more vertical—more intensive and classically urban—than that of suburban malls.

Other elements, in concert with this intense vertical cross section, contribute to a sense of urbanity: the colonnade at the edge of the balcony lends a sense of intimacy different from the vacuousness of typical mall spaces. The pitched skylights are reminiscent of nineteenth-century skylights and give a strong sense of daylighted interior space. More specific period references are found at a smaller scale: sconces and Tivoli lights, for example.

In relation to this concern for responding to the existing architectural and urban character of downtown, the most questionable decision at the Grand Avenue was the closing of Third Street. Did this disrupt traffic in and violate the perceptions of downtown? There is no evidence that the street closure has impeded the flow of traffic, and the closure does not hamper the movement of pedestrians. In fact, it invites pedestrians, for this is the principal entrance to the Grand Avenue. Although this modification in street pattern seems not to have been excessive, violations of

the character of an existing setting remain a concern in any project that begins to restructure downtown in dramatic ways.

Composition of People and Ingredients

Whereas homogeneity is a feature of suburban malls, downtowns are distinctively heterogeneous. Thus strong efforts were made to secure tenants for the Grand Avenue to mirror the character of Milwaukee and Milwaukeeans. In fact, "Rouse actively recruited local merchants for the center in order to give the Grand Avenue a distinctly Milwaukee flavor."[13] When the Grand Avenue opened, 48 percent of the tenants were local merchants, 12 percent regional, and 40 percent national.[14]

Although there is a legitimate criticism of gentrification when it overwhelms neighborhoods and eliminates housing for low-income people, the gentrification of downtown Milwaukee has not been exploitative but represents good planning. Historical precedent suggests that a healthy downtown is one with a mix of people, shops, and activities; in too many American cities it has become the sole province of the poor. To rebuild downtown Milwaukee and make it a center for everyone again meant understanding the values of and giving certain assurances to the middle-class shoppers on whom most strong commercial areas—and certainly downtowns—depend.

Image

The Grand Avenue had to reverse the image of downtown as unsafe, the home of undesirables. It overcame this considerable psychological barrier by reintroducing stores attractive to middle-class buyers, by locating parking close to shopping, and by insisting on a high standard of design. Further, the Grand Avenue is marketed not as competition for suburban malls but as something special: "It's an experience to be here as much as it is to shop here. . . . Extra touches lend an air of spontaneity, a festival feeling that you don't always find at suburban malls," says Paula Boyd, the advertising and marketing manager.[15] It is remarkable that in Milwaukee this transformation in image was accomplished in a matter of months: "The history of The Grand Avenue proves that downtown in its bloom could be a powerful magnet to attract the suburban and urban shopper. We proved that downtown's image could be changed virtually overnight."[16] Especially remarkable, the image of downtown was transformed largely through this single development.

Parking

To compete with suburban shopping centers, the Grand Avenue had to provide even more convenient parking at an affordable price. Covered parking for 1,350 cars adjacent to the Grand Avenue assures shoppers of a short, well-lighted walk protected from inclement weather. As a result, according to a Boston Store representative, customers feel safer here than they do in suburban malls.[17] The cost of parking has been adjusted to encourage short-term shopping and to discourage long-term use by office workers or people with time-consuming business outside the Grand Avenue.

5—

All Catalytic Reactions Are Not the Same

The chemistry for urban revitalization in Milwaukee depended on several elements, first among them the configuration of traffic and traditional uses of the setting. For example, the linear character of the Wisconsin Avenue commercial district is unlike that of cities whose shopping activities have developed around an intersection or a square. And because of land costs, access from freeways, and other considerations, parking tends to be concentrated.

Second, such unique ingredients as the Plankinton Arcade and service alleys parallel to Wisconsin Avenue give the Grand Avenue a configuration different from one in which stores fill whole blocks or where there is no inviting interior semipublic space. Further, the two existing department stores two blocks apart on the same side of Wisconsin Avenue argued for the linear character of the Grand Avenue. In a city with another set of existing elements, a different configuration for development would have emerged.

Third, socio-political and economic conditions were instrumental in facilitating changes. The individuals associated with the Milwaukee Redevelopment Corporation and those in city government helped both to make the Grand Avenue seem feasible and to implement it. The development of the Grand Avenue depended upon agreements to begin certain other developments, like the Hyatt Hotel and the new Federal Building. Then, too, the development probably would not have gone ahead with-

44.

Nodal, linear, and spread-form shopping centers. Stores in a cluster are the equivalent

of shops around a square; stretched out, they are like shops along Main Street. Either of

these configurations can be extended to create spread-form variations.

out tax-increment financing, which gave useful leverage: "We're taking something that doesn't exist to begin with and leveraging it to accomplish something else."[18]

In summary, center city developments must be conceived as unique collections of existing ingredients needing to be customized to satisfy new sets of requirements. Center city development calls for both idealism and pragmatism: idealism about the specialness of the place and pragmatism about making that place work in relation to contemporary traffic needs and local culture and values. This dual need calls for nothing short of a unique vision for each such urban place.

6—

Catalytic Design Is Strategic

Although much urban development is opportunistic ("Take advantage of tax credits; buy when prices are low; build what's profitable wherever you can"), better guarantees of profitability and urban quality can be had from strategic rather than opportunistic thinking. Opportunists think of the short term; strategists, of the longer term.

Goals

Catalytic urban design is based on formulas and programs, not specific plans and designs. It works not from a master plan, but from a master program. The distinction is now familiar to urban planners but is still worth repeating. Whereas a master plan specifies an end condition in the future, a master program sets more general objectives and identifies ways of achieving them. In effect, a program offers several ways to reach the objective—depending on circumstances. And it sets out intentions and methods but not solutions.

So, for example, a classic master plan establishes transportation, zoning, and land use patterns years or even decades hence and is typically inflexible in responding to changing circumstances; a master program sets out to stimulate and control development in a way more responsive to the exigencies and opportunities that appear in potentially volatile American cities. In short, a master program is flexible. The key to keeping strategic and catalytic design malleable is to have multiple rather than single-minded views of the future.

Zoning as Control, Guide, and Incentive

Stephen Dragos advised those concerned with the quality of Milwaukee's revitalization to be cautious. "Developers will jump at the chance to build near a Rouse project [like the Grand Avenue]. But Milwaukee must resist the temptation to jump at the first offer that comes along. . . . We have to ask: What do we expect? What do we want to happen?"[19]

New zoning restrictions for downtown Milwaukee are intended to direct the impact of new development strategically. Use districts have been identified: shopping, corporate headquarters, housing, government services, culture, and entertainment. Areas are designated, each with its own characteristics: shops and retail stores around the Grand Avenue; taller

buildings along the east bank of the river, lower buildings facing west from East Town; Kilbourn Avenue a "showcase boulevard," with hotels and other buildings along tree-lined walks; the brewery district near the Performing Arts Center a mix of shops, restaurants, and housing that has been converted from commercial buildings; warehouses and factories ringing downtown; housing in most of the districts. The new zoning plan assumes that riverwalks will be developed.

In addition to flexible land use considerations, design guidelines or development controls should be part of a city's strategy for shaping itself. Planners need to influence visual as well as land use design.

Sequencing Development

In the sequencing of development, as much as anywhere, the distinction between master programs and master plans is evident. Each step of a master program determines and depends upon previous stages and real events, not a scheme for a distant future. What happens and when is far more important than an image of an end product. For example, it would have been pointless to specify the Grand Avenue without predicating the Hyatt Hotel and Federal Building that made it feasible. Similarly, without the Grand Avenue and other connections, the skywalk system would make no sense; in its turn it made a riverwalk development logical. The riverwalk can eventually tie in to a theater district. And so forth.

Although such sequencing is a key characteristic of catalytic design, in fact in the urban setting events are seldom that controllable. It is probably more accurate to think of strategic design as a web of opportunities that are created and seized upon rather than as a linear development.

7—

A Product Better Than the Sum of the Ingredients

In Milwaukee the auditorium / convention center was an island. Now it is tied tightly to the Hyatt Hotel and to downtown by the skywalk system. The connections are practical, but the conceptual linkage of the disparate parts may be more important than practicality. The goal of any catalytic reaction should be not a collection of developments—so often the case in revitalization schemes—but integrative urbanism in which the parts reinforce one another and each is better for its association with the others.

Integrative Urban Architecture

Individually, few buildings in downtown Milwaukee are exceptional architecturally. But collectively they make a unique place. Marshall Field, Boston Store, Woolworth's, and the Plankinton Arcade had been separate entities. Now each is improved and more profitable because it has been related to the others in a meaningful way.

Relating these buildings has created large semipublic interior spaces where only one, the Plankinton Arcade, had existed before. In the pro-

cess, a new kind of architecture has been added to the city—yet it is not alien but has physical and visual precedents. The industrial aesthetic of the Grand Avenue design integrates turn-of-the-century glazed metal-frame systems and contemporary high-tech images.

Ongoing Catalysis

Careful redevelopment can mean economic development, which fosters further redevelopment: "The dream was to turn a somewhat dormant Downtown Milwaukee, into an alive and vibrant, moving showplace. The Grand Avenue does that. But it can do more. It can serve as the catalyst for other economic development in the Downtown area. It can be the source for hundreds of new jobs."[20] The vitality of a catalytic reaction has far greater potential than the visionless, haphazard process of opportunistic development.

Building Confidence

When citizens get more than they expected from public investment, when the very image of their city is recast through thoughtful design and strategic planning, they will give more and take part more eagerly. Even as the Grand Avenue was setting economic records and turning doubters into enthusiasts, critics wondered whether it would be a catalyst that sets off other actions or a development so large that it saps the community's resources. Critics also suggested waiting to see. But Dragos and others advised a different course: this was just the beginning. It was "not a time to pull back and say, 'Well, let's wait five years to see if this works or not.' What will make it work best is to take the next steps."[21] The wealth of projects precipitated by the Grand Avenue suggests that Milwaukee did not wait.

8—

The Catalyst Can Remain Identifiable

In chemistry the catalyst often disappears or is transformed in the course of a reaction, but this is usually not the case with urban chemistry. Instead, the ingredients of rejuvenation remain and contribute to the city's unique character and sense of depth. The layers of urban experience and urban history, the collage of styles and uses characteristic of a vital center city are the essence of urbanity. In fact, one of the pleasures of the center city is to trace and reconstruct the events that have produced its distinctive character: bold street grids; riverside industry; Main Street commercialism; technological bravado in iron, steel, and concrete; proud civic structures; and so forth. Total renewal and total design are largely discredited. A collage of overlaid urban visions and of identifiably different parts, an overlapping, sedimentary record of various decades and their architects, is much preferred. Cities are richer for the variety.

From the point of view of architects, that their contributions to the city are recognizable is good for business; at the same time they get credit for weaving in rather than imposing their own personal visions. In Milwaukee, the Grand Avenue intertwines with what has come before, amending and revising but not overwhelming.

45.

Sedimentation, accretion, and layering of urban form in Milwaukee.

It is taking the dedication of many individuals and organizations to regenerate Milwaukee. Institutional, civic, and political action set the process in motion and made possible the key factor, the Grand Avenue. Although the economics and politics involved in the catalytic process are of unquestioned importance, the focus of this analysis is catalysts as a tool in urban design. Just as investment begets investment, so too does (or should) good design beget good design. Buildings do set precedents, and these matter. The Grand Avenue is thoughtfully conceived and sensitively designed, and it has the potential to inspire other development, to improve the character and the quality of subsequent work, and to link up with existing and new construction.

To understand the importance of the catalytic concept in urban and architectural design, consider what might have happened had the Grand Avenue been different, had it been conceived and built as a suburban shopping center transposed to downtown. Would it have evoked the pride suggested in Brian Duffy's cartoon (Figure 36)? Would suburbanites have been induced to change shopping patterns and drive downtown instead of to the nearest mall? Would the Grand Avenue have restructured the rankings of commercial centers in the region?

There is a danger in urban development not only of failing to have an impact but of actually inhibiting new development through inadvisable actions. A negative catalyst is as much a possibility as a positive one. A development can act like a sponge in soaking up resources and activity, depriving adjacent areas. It can fail to inspire responses. Failure to light a spark can discourage others from investing time, effort, and financial resources. Programs, strategies, and designs need to be properly conceived if dynamic, productive catalysis is to happen.

We contend both that urban catalysis was necessary to accomplish what has been accomplished in downtown Milwaukee and what is continuing to happen there and that unilateral, univalent renewal could not have met the challenge. The accomplishment is considerable:

• A unique place is emerging, a place composed of and responsive to what was there before. It is both old and new.

• It is for many a new gateway to a city they had abandoned, thus helping to restructure the image of downtown.

• It establishes precedents for other developments—precedents in design quality, precedents for thinking about existing buildings, precedents for using the city, precedents for relating interior-oriented architecture to existing streets and street life, and precedents for an integrative urban architecture that is new in the experience of most Milwaukeeans.

Master plans could not have accomplished what has happened in Milwaukee and what continues to happen there; nor could functionalist,

46.

Catalytic reactions can take several forms: nuclear (top), multi-nucleated,

serial, and "necklace" (lower left).

structuralist, humanist, or formalist urban design concepts; nor could a raw pragmatic approach. To understand events in Milwaukee as well as in other American cities requires a concept like urban catalysis.

A discussion of the chemistry of urban architecture would be incomplete without reference to the people who make it happen. The urban chemist does not stand outside the process but is integral to and influenced by it. As Milwaukee demonstrates, effective people are as important to the catalytic process as a well-conceived, appropriately staged development. People get the process going.[22] In one city a corporation executive might be instrumental, in other cities a development corporation, a highly respected individual, a popular mayor, or an alliance of citizens.

The context in which urban design strategists work is less predictable than that of laboratory chemists. A collection of ingredients used according to a proven formula will not always yield a particular product or have a reliable consequence. The predictability of the laboratory setting decreases when the lab is a city. This is not to say that urban chemistry is entirely indeterminate and unpredictable, only that it is less predictable than chemistry in the laboratory and that it is subject to subtle influences. The catalytic process does not necessarily move methodically from step A through steps B, C, and D but might bounce around in a looser (though not random) fashion before achieving a desired end. The architect and urban designer Robert M. Beckley has related this semideterminate process to that of a pinball machine. The catalyst is unleashed within a limited field, but its precise path and its accomplishments are determined in part by inexorable forces (like gravity), skill with flippers, nudges, and accident. The human ingredient of urban catalysis is evident in efforts to set the process in motion; in considered use of flippers (knowledge, money, IOUs); and nudging at the right time and with appropriate finesse. In an indeterminate context, "chemists" are needed to keep the process going.

To elaborate further the concept of urban catalysis and to demonstrate that the process works in other cities and in cities of varying size, we examine a number of other cases in the next chapter.