Wendell Mayes: The Jobs Poured over Me

Interview by Rui Nogueira

Wendell Mayes was born on July 21, 1918. He came from Carruthersville, Missouri. He went to several colleges—Vanderbilt, Johns Hopkins, Central College of Missouri—without graduating. He became interested in the standard writers—Hemingway, Steinbeck, Dos Passos, Fitzgerald—and began writing in their styles until he discovered his own. He took up writing as a serious career after World War II, though never as a journalist. He first tasted real success in the days of live television and sold original teleplays in substantial numbers during the early fifties.[*]

| ||||||||||||

* This interview was transcribed by Gillian Hartnoll.

Wendell Mayes on the set of Go Tell the Spartans.

|

|

Television credits include the telefilms Savage in the Orient (1983) and Criminal Behavior (1992).

Academy Award honors include an Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium for Anatomy of a Murder.

Writers Guild honors include a nomination for Best Script for Anatomy of a Murder.

My first screenplay was with Billy Wilder, who brought me from New York to Hollywood for The Spirit of St. Louis in 1955. The great problem with the film was we had a man sitting in an airplane by himself, and the problem was how to sustain the interest in the story. I think it was a picture that was made thirty years too late, and I think it should have been called "The Lindbergh Story" or something like that, because when they put it out as The Spirit of St. Louis, everyone seemed to think it was an old musical, and they didn't know what the Spirit of St. Louis was.

There was something unusual about the way I was employed by Billy Wilder. He's a great bridge player, and he read a man called Goring on bridge at the time. He had had one writer working on The Spirit of St. Louis, and they had either disagreed or the writer got sick or something, and he was looking for a writer. And he was reading Colin Goring on bridge, and right next to the column was John Crosby's review of one of my television plays. He read that, and he called up New York and said, "Let's hire this fellow Wendell Mayes." So if he hadn't been a bridge player, I would never have been employed.

Billy Wilder's a writer, and we simply wrote a screenplay together, in a room together, walking around, talking it out, We would write a scene just as you would imagine a scene would be written. I would say, "Suppose he says this . . . ," and Billy would say, "Yeah, let him say that, and then he says . . . " It isn't the best way in the world to write, and it doesn't work for everybody, but it does work for Billy Wilder. We would scribble it down on a piece of paper, then call in a secretary, and she takes it out and types it, and then we look at it. That's the only collaboration that I've ever had. Everything else I've done by myself.

I wrote a picture that was before its time, which slipped by quite unnoticed. It was called The Way to the Gold, with Sheree North and Jeffrey Hunter, directed by Robert Webb. It was an interesting picture, but the studio and the people who publicize pictures didn't understand that it was a comedy. They thought that it was a big melodrama, so it slipped by.

Then I had a western, that I think was a superb western called From Hell to Texas. It was done by Henry Hathaway, with Don Murray and a darling actress called Diane Varsi, who very shortly thereafter quit films because she started a breakdown. Henry Hathaway is very easy for a writer to work with. He's absolutely dreadful for actors to work with: he's probably the toughest son of a bitch in Hollywood. He is tough for a reason: Hathaway is not the most articulate man in the world, and he maintains control of his set and of his crew and his actors by being cantankerous and rather cruel sometimes. He knows what he's doing; he isn't doing it out of hand. He's doing it deliberately because this is the way he's discovered he can work. It isn't true with a writer. He's a very gentle man when you sit down with him in a room to write. He doesn't feel that he has to browbeat you. I haven't come across a director who didn't make it as easy as possible for me to write. They actually try to conform to the way the writer works, rather than make the writer conform to some way they want him to work.

My first film that received notice was The Enemy Below, directed by Dick Powell with Bob Mitchum. It was not a financial success for some reason, although on television it has become one of the big pictures—but it got good critical notices. Its original ending was better. You remember where the German captain is on the submarine surrounded by fire, and the character played by Mitchum brings him across on a rope? All the men were off the ship but these two men. Now these two men were burnt-out cases, both of them. They are not there for any reason except that they have to be there. The moment Mitchum gets hold of him [the German], and starts pulling him aboard, the ship blows up, and at that point, you pull back to watch this tremendous explosion, and you keep pulling back until there's nothing left for the audience to see but the great, vast, empty sea with a little group of boats floating on it. The point was Dick and I both felt that these two characters were men who had no reason to live. There's much more feeling if they should die, one finally trying to help the other after killing him. But the studio said, "No, you like both of them. You can't kill them. It'll disappoint the audience." Nothing. So we had the ending with them standing smoking a cigarette on the back end of the destroyer, something like that. One of those things one must do.

Then I did a picture that wasn't so good, except it had an interesting idea that we were not allowed to follow through on—again with Mitchum and Dick Powell—called The Hunters. It was about a man who loved war, but we had a problem trying to sell a hero who loved war. I know The Hunters was supposed to be an adaptation, and the novel was an interesting novel. I was

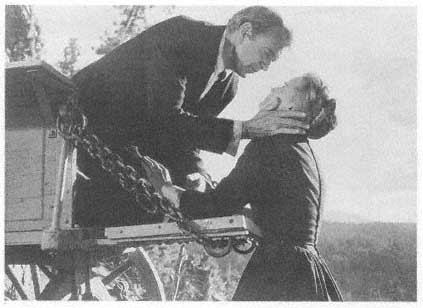

"A woman's film rather than a man's": Gary Cooper and Maria Schell in Delmer

Dave's film The Hanging Tree.

called in on it, actually, in desperation, because they had a starting date, and they really didn't have a script to shoot; and while we used the title, what I wrote was from start to finish an original screenplay. There wasn't anything else to do, because the novel could not be adapted. It was too internal. They do make mistakes in Hollywood in buying material. They will buy a novel that is terribly internal, and the only way you can really do it is if you have a voice-over explaining what the character is thinking. In doing a film, your characters can't think; they can only speak or move, and you've got to tell the story with their voice or their movements. What they're thinking, nobody knows.

Then I had a western—I think it was Gary Cooper's last western—called The Hanging Tree, directed by Delmer Daves. Daves is a writer himself. He's very easy to work with, a very sweet man. Cooper wasn't very well, and I know that he had great trouble riding a horse at the time, because he had something wrong with the hip; so they kept him off the horse as much as they could. It was the only western that I think that I've ever seen that was a woman's film rather than a man's film—Maria Schell playing the blind heroine was marvelous.

Gary Cooper was a very interesting, a very complex man. He was not a simple person at all. I think he was one of the best actors film has ever had. I

don't think anybody recognized it, even though he won—I think—two Academy Awards.[*] Henry Hathaway was the first to point out things to me about Cooper, before I even worked with Cooper. He said, "Everything Cooper does is original. He thinks about it. You have to watch it to realize what makes Gary Cooper on film. You don't just stand him up there; it's things that he does." He said he had Cooper in a film, and there was a gunbelt hanging on the wall; and Cooper's direction was to go over and take the gunbelt off the wall. In the rehearsals, Cooper kept fooling around with it, and Hathaway said, "Coop, what are you doing? Just take it off the wall." And Cooper said, "I want to take it off my way." So Hathaway said, "All right, do it your way," and Cooper fooled around with the belt for a few minutes and said, "Okay"; and they rolled the cameras, and he walked over an instead of grabbing it off the wall, he took two fingers and he placed them under the belt and he lifted it off the wall. Hathaway said no one in the world but Gary Cooper would have done that. That was why he was so original. Those who say that Gary Cooper hesitates over his lines because he doesn't know them are lying. He was a professional, like John Wayne. Cooper and James Stewart—both have a great sense of timing in dialogue. It's more recognized, and I think it's easier to recognize, in Stewart than it was in Cooper, but Cooper was highly original at the delivery of lines. He knew what he was doing.

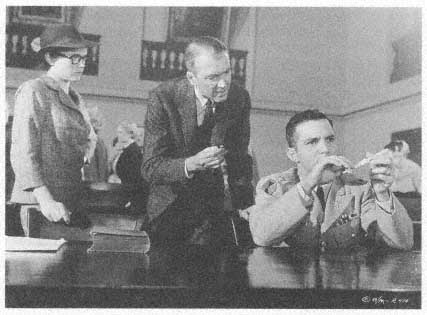

Then I did Anatomy of a Murder for Otto Preminger. It was a good movie. I think it was one of my best screenplays. And I did two other pictures for Otto—Advise and Consent and In Harm's Way. I wrote another script for him, but it never did get off the ground, not because of the script, but actually because the rights to the material were confused—that was Steinbeck's Cannery Row.[**] So it sits on the shelf, but maybe some day it will be made.

No one was cast when I started working on Anatomy of a Murder. Stewart was cast after it was written. Lana Turner was cast and then stepped out, and Lee Remick came in. It was written without any actors in mind.

I didn't know Otto when he called me from New York. I don't really know how he got on to me or why he employed me. But he called me from New York and asked me if I'd read a novel called Anatomy of a Murder [by Robert Traver[***] (New York: St. Martin's 1958)], and I said, "No, but I will read it." And I read it and called him back, and I said, "I think it's a filmable motion picture." So he called my agent and made a deal, and I went to New York and met Otto there and started to work on it.

* Gary Cooper won Oscars for Best Actor for Sergeant York and for High Noon. In addition he received a special Academy Award in the 1960 ceremony shortly before his death.

** Cannery Row was made into a film in 1982, the directorial debut of screenwriter David S. Ward (The Sting ).

*** Robert Traver is the pseudonym of John Donaldson Voelker.

From left, Lee Remick, James Stewart, and Ben Gazzara in Anatomy of a Murder.

When I work with Otto, we discuss over a period of time, say, the first fourth of a screenplay, where we want to go with it; and then I will go off and sit down, and I will write the first fourth. Then I come in and Otto reads it and we discuss it again and we get the construction and the arrangement of scenes to please both of us. Then we move on to the next fourth of the story. I've never gone through a whole screenplay with Otto and then gone off to write, because Otto doesn't like to plan that far ahead—and actually, I don't either because sometimes good things come without planning step-by-step straight through a screenplay. With other directors, I have gone off and written a screenplay and handed it to them. They've asked for certain changes, and that was it. Otto's very good from a writer's point of view. Unlike many directors and producers, Otto does not make up lines when the writer isn't there. He will call the writer and say, "Look, I need a line of dialogue here." One of the things that drives a screenwriter absolutely crazy with many producers and directors is that they won't call the writer; they will simply toss in ad lib lines of dialogue that are almost invariably absolutely dreadful, that the characters wouldn't say. It isn't really done quite so much anymore. They used to hate the writer, and the moment they got the screenplay, they used to say, "Get off the

lot; we don't want you around bothering us." Nowadays, a writer out here has a good deal more respect and a great deal more money.

I've never worked as a contract writer. That was before my time. I've always worked on one specific film for a flat fee. But I've never been driven to write fast just to get the money. I suppose there are writers, particularly in television today, who crash the stuff out as fast as they can and then rush onto something else; but the flat deals paid writers now are very substantial, and they're usually paid enough to work a year very comfortably.

Advise and Consent was actually a rather close adaptation for a very good reason. It was [based on] a very big best seller [by Allen Drury (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1959)]; and when you sit down to adapt a best-selling novel, you do feel that since ten million people have read the novel, they must like it, and they want to see what they've read. So we made a great effort to try to translate that book to film. The introduction of most of the characters by the phone is not in the book, but we had to introduce a great many people very fast in order to start the thing. What was on film was very close to what was in that novel, and I don't mean dialogue necessarily, because very few novelist write dialogue that actors can speak. It was the same thought that was in the novel but not in the same words. We put in the scene with the ambassador's wife visiting the Senate chamber, which was not in the novel, very obviously for the European audiences, because if you talk about a Left and Right in Europe it means something entirely different from Left and Right in the Senate.

I don't believe that the scene was in the book where [Henry] Fonda confesses to Franchot Tone as the president that he was a member of a Communist group, and Tone tells him that he must not tell the truth about this, because it is more important that he should continue his political career and follow him as president. I don't think that Fonda did go to the president, but I think that the president knew. I've forgotten what device they used in the book, but we did that largely because we felt that the character of Fonda, as we were presenting him, was a very sympathetic man, and that he was an honorable man, and that he would have done this. In the novel, he did not. The author of the novel, Allen Drury, hated the picture. He's very conservative-as a matter of fact, he's an archconservative-and Otto and I are liberals, so we didn't do justice to his conservative point of view. His character of Leffing-well, the part Fonda played, was not a sympathetic man; he was a crook. I believe that Drury was immensely more sympathetic to the Charles Laughton character. Don Murray's [character's] problem of homosexuality was in the novel, but the scene where he goes to the gay bar was mine, that was original. I did that, rather than use dialogue exposition of what the situation was, because we could show it. In the novel, someone told it. I don't think he ever encountered the man who had been his lover at all. But, still and all, it told the same story.

I was least fond of In Harm's Way out of the three pictures I've done for Otto, and this was probably because it seemed to me to be a twice-told tale. It was a war picture that had been done before, the kind of thing that had been done many times before. There were things in it I liked very much. I thought that the love story between an old admiral and an old broad came off awfully well, and because John Wayne and Pat Neal were marvelous in the roles. John Wayne's a great pro. John Wayne never blows a line. He'll come in letter perfect. The other actors will blow lines, but he will stand there patiently, wait for them to get their lines, say his in his own way.

It inhibits me to know who is going to play a part, because in a scene in which I know, for example, John Wayne is going to play a role, I will say to myself, "Well, John Wayne can't say that line of dialogue," so I won't write it. Now in In Harm's Way, John Wayne was hired after the screenplay was written. It was not written for John Wayne, and if I'd been writing it for Wayne, there are certain speeches that I would not have written, because I felt he could not read the lines. As it turned out, John Wayne was able to read the lines and read them very well indeed—so I think it was a better film because I didn't know he was going to play the role.

I wanted Wayne to die and the son to live, and Otto wanted the son to die and Wayne to live. His argument was—you can't kill John Wayne. So he won, and perhaps he's right. You can cut a leg off or an arm or an ear or something—you can maim him for life—but you can't kill him.

I wasn't crazy about Brandon de Wilde as the son. There was a good scene where Wayne first meets his son after all these years, out on a little boat where he and his son have this—actually—a conflict that they don't really talk about; you just feel that it's there. This is a good scene. Some of it I actually didn't really believe. I always find it difficult to believe anything, because it always seems so convenient to me that characters turn up in the proper place at the right time. I know audiences don't think about it, but as a writer, I think about it. I don't like things to be convenient. Maybe this is another reason why I was not terribly fond of In Harm's Way. I think some of Otto's best direction was in In Harm's Way —unquestionably, it was. Dana Andrews's admiral was really a bit, but Dana Andrews was remarkably good in it. It was not a caricature; it was a very believable officer.

I didn't much care for the Kirk Douglas character. I thought he was sort of dragged in. He had a few things that were rather good, but actually that gung ho, derring-do, flying the plane after raping the girl, somehow doesn't seem part of the story to me; it seems like something else. I could have written a picture about the character that Douglas played. If we could have done more with the character, it would have been more interesting to me.

Otto can be very stern with actors, he can actually be very cruel, he can be very loud. You see, Otto is an actor, and he has great discipline as an actor, as a director. He himself is a disciplined man, and he expects other people to be

disciplined. I think probably the thing that Otto detests most of all is an actor who is not a professional, who does not behave as a professional. A man, or a woman, is being paid a lot of money to come on the set, read some lines, do a job, and instead they want to exhibit their egos, and this Otto will not contend with. Many directors have another way of working . . . I think Richard Quine is inclined to want to charm the actors.

I had a great deal of freedom in In Harm's Way. I wrote the first screenplay, when Otto was in Europe, without him at all; and then I went to London and started to do a rewrite, and Otto shelved the project. And then I believe it was about maybe two years later that the picture began and [I] had a fresher point of view and did many things that were not in book at all. And I think we improved it for that reason, since we had quite forgotten the novel.

I also wrote Von Ryan's Express for Mark Robson and Hotel for Richard Quine. Hotel was a big best seller and Warner Brothers employed me to write a screenplay and to produce the picture. The studio felt that Richard Quine and I would get along well together, which we did, so he came in as director. We had a terrible time casting it. It was one of those situations where the studio wants to make a picture because they need something to take care of their overhead. They had nothing shooting, so we had to move very quickly in the casting. We all recognized that it was an old-fashioned formula picture, and perhaps if we had had bigger stars, it would have gone at the box office as well as Airport [1970].

I am very fond of Hotel, but afterwards, I swore I'd never produce anything again. I took the producing job because Jack Warner was a friend of mine. When he called me and asked me to do the book, he said, "Listen, could I ask you to produce it and save me some money?" I said okay. But I found producing to be the most boring occupation I'd ever encountered. The detail that you have to be burdened with is just not worth the effort—like whether one of the actors should have pockets in the rear of his britches. And you have to be on the set all the time. Shooting motion pictures is a very tiresome job.

If you ask me what kind of person Jack Warner was, my answer will be a cliché: he was a showman. Zanuck was a showman. Harry Cohn was a showman. All these people were showmen, and that's the only way to describe them. They were in the business from the time they were sixteen years old; they grew up in it, and they had the feel and scent of show business about them, which doesn't exist now. Jack Warner would make a decision about a piece of material, not because it would make a lot of money, but because he liked it as a story. If you look at the studio's record of motion pictures, it's a fascinating record. And Jack Warner was the person that said yes to all of them.

He was also involved in the scripts. Now, that isn't true anymore. If a writer is working on a script for 20th, Paramount, or any of the studios, he never meets the man running the studio anymore. As far as I know, the man running the studio doesn't even read the scripts anymore; he's too involved with the corpora-

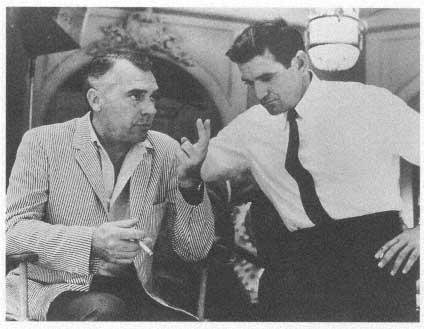

Wendell Mayes with Rod Taylor on the set of Hotel.

tion. But when you wrote a script at Warner Brothers, you dealt with Jack Warner. You went and sat in his office. He had read the script, and he had notes in the margin of his copy for you. He told you what he liked and he didn't like. Look, Jack was a very astute, hard-nosed businessman when it came to dealing with the people who worked for him. A lot of people didn't like Jack Warner. But I've discovered that the people who didn't like Jack Warner were the people who didn't get what they wanted from Jack Warner. And I was very fond of Jack Warner because he was kind to me when I was young.

I've had a lot of disappointments. In Hollywood, everybody does. But I'll tell you about my greatest disappointment. There was a producer, David Weisbart, who was a close friend of mine, who had made many pictures, all of them quite small, none of them exceptional except Rebel without a Cause [1955]—as a matter of fact, he produced The Way to the Gold, one of the first things I did. And he had this dream of making the definitive great picture about General Custer. So he said, "Would you be interested?" and I said, "How much time would you give me?" and he said, "All you want. We'll pay you for as long as you sit and write it." So I began my research, and it took me a year to get it down on paper. It was a fascinating theme—it was a Greek tragedy in a western. The forces that produced the battle, I won't even try to

tell you, but how it came about is one of the most fascinating things that you can imagine. It had never been researched properly. We sent it to [the director Fred] Zinnemann, and he called from London and said, "I'm mad about it. Will they hire me?" And they hired him, and he came over, and we began to cast and look for locations. In the meantime, they were budgeting the film. They asked for absolutely no rewrite because Zinnemann said, "This is it; we shoot"—which is very pleasing to a writer, of course. They hired Toshiro Mifune to play Crazy Horse, a great piece of casting, and they were not reaching for any big stars at all . . . he would probably have been the most prominent name in the thing. Very early on, when I started to write it, there was discussion with Charlton Heston. I had lunch with him one day, but Zinnemann didn't want him as Custer. Before Zinnemann, there was some talk of Kurosawa doing it, but it was decided that the language barriers would be just too much for this kind of massive undertaking.

One of the things that was going to be marvelous in it was: the battle occurred on June 25th, 1876 . . . the first part of the film would be fairly standard-size film, but on that day, in the middle of the film, the screen would begin to open until you're in Cinemascope for the rest of the picture.

Well, the budget came in at eighteen million, and the studio said, "Well, we'll have to shoot it in Mexico; we can't afford that much money." And this infuriated Zinnemann because he said, "How can you make a picture about Custer with Sioux Indians in Mexico. We've got to go where it happened. We've got to go to Montana." But they tried to find some locations in Mexico, and they got the budget down to fifteen million, even though Zinneman was very unhappy about it. But even that was too much, so the studio decided to shelve it because it cost too much, and they had to pay Fred off, and we went miserably back to London.

Later, there was a Custer picture in Spain, a cheap movie starring Robert Shaw. Interestingly enough, Robert Shaw was going to be our Custer. I guess he'd fallen in love with it, so that he still wanted to play Custer, regardless of whether it was a good or bad movie. Anyway, that script still sits at Fox. Maybe some day they'll make it.

I'll tell you what was attractive about The Poseidon Adventure: the money I was offered. I knew that it was going to be a big, bad, popular motion picture. I was the first writer on it. After I did a couple of rewrites, I asked the producer, Irwin Allen, to please relieve me of the job. I had done all I could. Then he brought in Stirling Silliphant. Stirling worked on it and changed it quite a bit, enough so that I think he got first credit.[*]

* Stirling Silliphant does receive first credit, followed by Wendell Mayes's name. See the interview "Stirling Silliphant: The Fingers of God" elsewhere in this volume for an additional perspective on The Poseidon Adventure.

The reason The Bank Shot [based on the book by Donald E. Westlake (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972)] turned out to be such a strange movie is because the director was Gower Champion, who had never directed a movie. I loved [Donald] Westlake's novels, and I felt that Hollywood had never truly done justice to his peculiar brand of humor in motion pictures. I was trying to do that brand of humor, something that is just slightly titled, which at first you don't realize is slightly tilted. It was a charming idea, this Westlake book, the idea of not simply robbing a bank but stealing the whole building. What happened is that Gower tried to turn it into a farce, and it didn't work. The people weren't equipped to play farce. Gower was a nice guy and a marvelous stage director; but the film simply wasn't deft, and it should have been. He held pretty much to the script but ruined what I thought was a good piece. He was the only bad experience I've ever had in my career with a director. I was bitterly disappointed.

Around the same time I was also working on Death Wish. I think the first studio involved was United Artists. Because I'd worked for Otto Preminger at UA [United Artists], Arthur Krim was a friend of mine, and through Krim, Hal Landon, the producer, sent the book [Death Wish, by Brian Garfield (New York: McKay, 1972)] to me. I was immensely intrigued with the book. I must tell you, from the moment I read it, I knew it was going to be a blockbuster because it was coming at just the right time. The outrage at crime in the streets was a big item. It didn't surprise me when I read in the papers later on—I was in London at the time of the opening—that audiences were stamping their feet and screaming in the theaters.

I had a great deal to do with how the film turned out; I could see it in my mind before I put a word on paper. I didn't stick to the book very much. I had to do an awful lot of inventing, which I must say [the author] Brian Garfield was not very happy with. But sometimes novelists are not happy, and there's not much you can do about that. I think when novelists sell to the motion pictures, they should do what Hemingway did, and just walk away and forget about what might happen to their work.

Go Tell the Spartans took about eight years to get produced. I really didn't have much hope of anyone ever buying it. But I was fascinated with Vietnam and why nobody had made a picture about Vietnam. The Green Berets [1968] was a gung ho picture; it could have been World War II. Vietnam was an absolutely fascinating war, however. The political ramifications are quite fascinating because it [military involvement in Vietnam] tore this country asunder the way it tore France apart. The same thing happened here that happened there, and to an extent, this is what my story was about. It took place in 1964, shortly before escalation when all the soldiers were professional, and they were fighting the war the same way the French had fought the war, with these little outposts everywhere. A group of American advisers with a company of Vietnamese are sent to regarrison an old French garrison that was deserted in

Burt Lancaster (at left) and the troops in Go Tell the Spartans , directed by Ted Post.

1953. There is a French graveyard there of three hundred graves. Nailed on the tree is a sign in French that says: Stranger, Go Tell the Spartans That We Lie Here in Obedience to Their Laws. Now you know that exactly the same thing that happened to the French is going to happen to them. My script wasn't gung ho; it wasn't anti-American; it was, I hope, the truth and an interesting tale.

When I first submitted the book [Incident at Muc Wa, by Daniel Ford (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1967)] around town, they ran screaming. Fox ran from it. Paramount ran from it. They all ran from it. They would not make a picture about Vietnam. So I took an option on the book myself and wrote the script and started, slowly, pushing it, peddling it. I carried the option all those years. I had optioned several other things over the course of time, which I had written screenplays for, but this was the first thing that I optioned that finally did go. It was also one that I was in love with. I could see how the relationships of the people who were in the novel could be turned into a story, a war picture that could really get hold of you.

The script isn't faithful to the book at all, incidentally; but the novelist loved the movie. I sent him the script, and he wrote me a little note, saying he wished his novel was as good as my screenplay. That was very sweet of him. For one thing, in the novel there was a newswoman wandering through the story, and I eliminated her completely. I invented some characters that were

not in the novel. I made the story much more of a tragedy; the wipeout at the end [of the film] was not in the novel. And the part [Burt] Lancaster played was much stronger than in the novel. He was not a man who had been a major, for the curious reasons I gave him, all of his life. All this and more was invented.

Finally, one day, Teddy Post called me. Ted hasn't done a lot of features, he got stuck in TV; but he's a good director who has never been recognized for his real talent. He had read the script and remembered it. He was working for the American Film Company and called to ask, "Whatever happened to that script of yours about Vietnam that I read a few years ago?" I said, "I've still got it." He asked me to send it over to him, and within three days, he called back and said they're going to go for it. Just like that. The American Film Company was prepared to go with anyone they could get. Burt Lancaster was the first one they submitted it to, and he said, "Yes, I'll do it. Let's go." He didn't ask for a thing, not a single line change.

The filming was done right out here near Magic Mountain, down near a little river, and if you panned up too high, you could see Magic Mountain. They had to do extra work on the sound, because when they were shooting at night, you could hear the roar of the freeway. Some of the cast were Vietnamese refugees; some had been officers. I thought Lancaster was wonderful in it. He put up some of the completion bond himself. The picture was made for a million bucks, and I think it's better than Platoon [1986].

I had gotten into the habit of adapting already established material. Not by choice. If I had the courage just to sit down and write originals and get them on the market and try to sell them I would have, but I'm afraid I was a coward and decided the money was awfully big for these things I was being offered. And it was a period, when I first came out here, where very few original scripts were being made. The studios wanted preconceived material. There were a few occasions when the reason I did something was quite simply money, but what generally attracted me was not action, not plot, but the human relations that occur during the story. Generally speaking, I did choose material that I liked; so if some of the pictures were not very good, it's my fault.

The world changed out here in the late 1970s, and that's one reason I started to write originals. I had one original made, at the beginning of the change. I called it "Love and Bullets, Charlie." They shortened it to Love and Bullets, totally destroying the whole idea of the title. That was a [Charles] Bronson picture. I wrote a very tricky script in flashback: A man was hired to bring a gangster's moll from Switzerland back to the States, where she would confess to certain things, implicating certain gangsters. She was killed en route. The man hired to bring her back realizes, through some clue, that maybe the gangsters didn't kill her. Somebody else might have done it. So he sets out to retrace his steps. Now, in retracing his steps, someone is trying to

kill him, while in flashback, what has already happened takes place in continuos action; so what you had was a continuous action, past and present. A very interesting concept.

They sent the script to John Huston, and he went for it. They flew me down to Mexico. I was down there with John for a week in his jungle compound. He loved to be the patrón, you know, and had built this strange compound that had no telephones, its own generator, with houses made of canvas that opened in the daytime. He had a whole tribe of Indians serving him. I had met him before, but I never had the opportunity to work for him. He was very enthused with the script. Then I came back to the States to work on it, incorporating his suggestions. In the middle of this time, he had an aneurysm and had to have a quick operation. Then he was off the film. They brought in another director. The changes he wanted to make would destroy what I had written. I told the producer that I would prefer to walk away. So it was rewritten, and the idea of the flashback and the double action was gone; and what audiences saw, although my name is on it for story and as screenwriter, is half of what it was.

I must tell you, I didn't come out here with any rosy ideas of being an artist. I was an actor in the theater. I didn't really know much about motion pictures. I had always known I could write. When television began to rule in the early days, I realized, when I was at liberty, that I could probably write something that could sell, and I sold the first thing I wrote. Then I sold four or five others. Then Billy Wilder picked me up and brought me out. If you collaborate with Billy Wilder, you have a career.

I was by this time well into my late thirties. I wasn't doing well as an actor. I knew if I was going to have any money, I'd better grab the chance. The jobs came fast. They were pouring over me, and they poured over me for twenty years. I could pick and choose. and there were a couple of years that I didn't even bother to work. But I never got over my love of the theater. I had great respect for motion pictures, but it was not something I had chosen to begin with. I fell into it. I'm not mocking motion pictures, understand, because I've done awfully well out here.

I haven't really done that much in the 1980s. My career was winding down anyway. The young people were coming on. The town was full of young writers fresh out of school. They could be gotten cheaply. Some of them turned out to be pretty good. Most of the writers of my generation were allowed to go to grass. There's no question that there's a lot of heartbreak among some of the older writers and directors. Happily, I was one of those that it didn't really bother, because I was quite ready to stop being hired.

The people who run the studios nowadays all seem to me to be stamped out of the same cloth. They're film-school people, and what they know is what they have been taught in film schools. I don't sense any original minds at all. I'm not saying there aren't any original minds, but in my few encounters—I'm pretty well retired, except for the things I'm writing myself; at least I'm no

longer for hire—that's the sense I have. There may be some very talented people in the studios. I haven't met them if there are.

Hollywood studios are conglomerates now. When I came out here, I got in on the tail end of old Hollywood. It was quite wonderful. What has changed in the studios now is that they simply are not happy places. The fear is tangible. There is no continuity of employment for people. The managements of the studios are icy. They don't know the people down the line like they used to. All that has changed, and I don't think for the best.

When I interviewed Wendell Mayes in October 1991, he had just gotten out of the hospital after undergoing tests and treatment. He had read the first two Backstorys, and was eager to cooperate for a session that would update his 1972 Focus on Film interview, with Rui Nogueira. Mayes told me he was in some pain and asked if I would mind if he stood for most of the interview. Yet he looked fine—handsome and radiant, with an ascot around his neck, like an actor in the winter of his years—his humor seemed good, and he was patient with my questions. When I told him that later on I would be sending a photographer around to take a portrait of him for the book, he said, "Send him around soon. At my age I might be ill. Who the hell knows, I might be dead." I thought he was kidding.

The photographer did not get to him in time. Mayes died of cancer on March 28, 1992, at age seventy-two. In later years, he had been working on some pet projects, both original ideas and adapted scripts, one of which came to fruition after his death. The ABC television movie Criminal Behavior, starring Farrah Fawcett, from Mayes's teleplay, was broadcast in May 1992. An adaptation of Ross MacDonald's The Ferguson Affair (New York: Warner, 1960), with MacDonald's male lawyer transformed into a female protagonist, it was vintage Mayes—boasting an intricate plot, raucous characters and clever situations, bristling dialogue—a terrific sign-off for a long and impressive career.—P.M.