Proposals for a Natural History of Plants

Between 1550 and 1700, the number of known plants quadrupled while the number of botanical compendia declined.[2] If only to take account of discoveries, a new natural history of plants seemed a necessity in the late seventeenth century. In 1674 John Ray pointed out the absence of a "general History of Plants." He complained that in order to have the available botanical lore in a single work, it would be necessary to combine the publications of Bauhin, Columna, Alpin, Cornut, Parkinson, Margrave, Morison, and Boccone.[3] Most of the authors he cited were no longer active. But when Ray wrote, members of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris had already committed themselves to just such an undertaking as he described. One of their earliest plans was to publish a general natural history of plants.

Huygens was the first to propose that the Academy publish a natural history. The project he described was Baconian and all-encompassing, intended to investigate weight, heat, cold, light, color, magnetic attraction, the composition of the elements, animal respiration, and growth in metals, plants, and stones.[4] The Academy would assign topics to its members, who would report weekly on their findings. This stilted proposal helped convince Colbert and his advisers to found the Academy, but Huygens's colleagues modified his ideas and adopted two specific projects for the anatomists, botanists, and chemists. These were the natural histories of animals and of plants.

It was Huygens's friend Perrault who suggested in January 1667 that the Academy publish a natural history of plants.[5] Perrault too was influenced by earlier models, especially Bauhin's Pinax, which Nicolas Marchant had already begun to revise. Perrault tried to define the field and to differentiate the kinds of research required for a comprehensive study of plants. He identified two ways of studying plants: "pur Botanique et Risotome" and natural philosophy. The former studied the "histoire" of plants by "botanizing" or "herborizing," that is by collecting plants and roots and studying their external characteristics and medical applications.[6] The latter Perrault defined, in the Theophrastean and Baconian tradition, as the inquiry into the causes of medical properties of plants or of vegetable reproduction and nutrition. For such research he envisaged chemical analysis, microscopic observation of seeds and shoots, tests of theories about propagation and generation, and studies of whether sap circulates like blood.

Perrault's plan of research for the natural history was more bookish than

experimental. It was at once grandiose and modest. The Academy would treat all known plants in a comprehensive publication containing descriptions, illustrations, and a topographical index, but would take its information from existing literature. Because classification was problematic, Perrault proposed that academicians choose an existing system or dispense with one entirely. A catalogue of all known names of plants would be useful, but ancient names and descriptions could not always be correlated with modern plants. The compendium would be illustrated from watercolors painted by Nicolas Robert for the duke of Orléans rather than from life.[7]

Like Huygens, Perrault had a traditional conception of natural history. He referred to the ancients but not to the Americas, and indeed the Academy looked primarily to Europe and the Near East for unusual species, leaving American flora to the Minim Charles Plumier. As a physician, Perrault also stressed the medical merits of the project, urging academicians to correct and expand materia medica. The Academy's task was to collect useful information as efficiently as possible and make it available to the public.[8] This literary approach especially suited a society that had existed formally for only one month, as yet possessed no laboratory and little apparatus, and still used meetings to plan or debate. Perrault was also uncertain about the extent of royal patronage. A modest proposal, firmly rooted in work already begun, stood a chance of succeeding and might stimulate a more broadly conceived project, if only Colbert would authorize it.

By criticizing Robert's paintings, Perrault ultimately justified expanding the Academy's project. He showed that aesthetic criteria did not meet scientific needs. Most of the paintings did not show roots or indicate the relative size of a plant, defects that would trouble a scientist but not a connoisseur. Perrault's remedy was to add the missing roots and to depict leaves, fruits, and seeds in blank corners of the page (fig. 2). Should the Academy be allowed to commission illustrations from life, however, Perrault recommended that the artist portray the plant life-sized or provide a scale and show the important parts of plants; when the appearance of a plant changed markedly as it grew, the artist should depict both the young and the mature plant.[9]

Perrault's colleagues were not content with studying books but wanted to study nature. They would start with the literature and go beyond it. Indeed, since European botanical literature referred to only a small proportion of known plants, the greatest need was to study the new or "rare" plants. Here, too, the Academy was influenced by work begun by Guy de La Brosse and the duke of Orléans, especially since Marchant had worked

Fig. 2.

Lychnis umbellifera montana helvecita/Lychnis à umbelles.

(From Estampes; drawn by Robert, engraved by Chastillon;

photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

for the latter at Blois. But the Academy also added an experimental twist to Perrault's natural history by incorporating chemical analyses designed to explain what they were describing. This was Duclos's contribution to the project.

As director of the project, Duclos quickly put his own stamp on it.[10] To the basic elements — engravings and descriptions of plants — he added a classification according to Theophrastus's system.[11] He also expanded the descriptions to compensate for the faults of the illustrations. Descriptions of the size, parts, and products of plants would form a catalogue of characteristics that would distinguish one plant from another. He stressed for example the "carriage" or appearance (le port ) of the plant in the earth, that is, whether a plant was tall (eslevée ), or rested its branches on the earth without sending out roots from them (couchée ), or rested its branches on the earth and sent out roots from them (rampante ), or leaned (appuyée ). Duclos also demanded precise descriptions of the root, trunk, leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, and natural products such as gums, resins, or liquids.

In a more radical departure, Duclos added chemical analysis to the work. He planned to distill plants in order to mention in the descriptions the consistency, color, smell, and taste of distillants. He hoped to discover the chemical constitution of plants by analyzing their distillants, by testing a decoction of sap or juice in various solutions, and by studying crystals formed by condensed juices.[12] Because Duclos believed that chemical explanation of organic matter was fundamental, he made chemical analysis an integral part of the natural history of plants. Under the guise of description, therefore, he introduced inquiries that bordered on natural philosophy. In so doing Duclos set the natural history on a new and difficult footing that made the project controversial and delayed its completion.

Duclos also thought the natural history should have a regional bias, focusing on French flora. Thus, he recommended that the common French names be in the list of synonyms of plants:

And because we plan to write this natural history in the French language, it would be good to be informed about the names which the common people in the major French provinces give to each plant, so as to add them to the names used in other languages.[13]

The natural histories of plants and animals, like nearly everything academicians wrote, were published in French. The Academy intended to reach above all a French audience. First and foremost, that meant the king, the ministerial protectors, and the persons to whom they distributed the book, as a group probably unfamiliar with Latin. Duclos's interest in popular

French names for plants was controversial, however, and his proposal allied him with the "moderns" against the "ancients" and with the "realists" against the "purists." The same controversy raged in the Académie française, which ruled out of its dictionary neologisms and technical language, the very vocabulary that Antoine Furetière struggled to learn for his own dictionary. Within the Academy of Sciences Duclos had many allies, for academicians coined words so that they could write about plants in their own language, and in the 1670s French names were added to some of the plates.[14]

Duclos's request that the Academy study only French plants was less palatable, despite its advantages. Valuing experience over authority, Duclos wanted descriptions to reflect direct observation, which was possible only when the plants were near at hand. He believed that the provincial flora of France were insufficiently appreciated in scholarly circles. He wanted the Academy's project to be manageable, and he worried that plant species varied when transplanted. Academicians, however, resisted this restriction. In the late seventeenth century gardeners were proud of the exotic flowers and fruits they could cultivate, and Louis XIV's nurseries and orangerie were famous for defying climate and seasons. Connoisseurs and savants alike wanted to expand their knowledge of flora and fauna, not limit it to what was native to France. Although Duclos's proposal was formally approved, the Academy never stopped cultivating, describing, and illustrating rare plants and never limited its projected book along geographical lines.[15] The resulting lack of focus impeded the project.

The Academy accumulated proposals and smoothed over disagreements. Its corporate procedures and plans grew by accretion and ignored inconsistencies. The successive adoption of Perrault's and Duclos's proposals exhibits this tendency well: in some areas they agreed, in others they disagreed, and the Academy simply glossed over any problems of coherence between them. Where Perrault and Duclos were in harmony, they reflected a centuries-old approach to studying plants, with Perrault emphasizing illustrations, Duclos text, to convey information. Duclos also improved on Perrault, whose language had sometimes been vague. But Duclos wanted the natural history to concentrate on French flora and to include chemical analysis, which Perrault regarded as more appropriate to the natural philosophical studies of plants. In any case, when the Academy formally approved Duclos's recommendations in 1668, a basic framework for the natural history existed. The designers were Huygens, Perrault, and Duclos, but the research and writing were almost entirely the responsibility of Nicolas Marchant and Bourdelin.

Duclos quickly lost control of the project to Dodart, who entered the Academy in 1671. His statement of principles appeared in the Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des plantes , published in 1676 with Marchant's Descriptions de quelques plantes nouvelles . The books were an inconsistent introduction to the project, for Dodart discussed chemical analyses of plants at length, but Marchant omitted them from his descriptions.[16]

Dodart accepted many of Perrault's and Duclos's criteria for describing plants; he also learned from Marchant's experience of writing descriptions. He reaffirmed that the Academy's goal was to publish a description of every known plant. He agreed with Perrault and Duclos that the function of any description was to enable the reader to distinguish one plant from another. As a result, he limited descriptions to the parts of plants that served this purpose, or that helped to discover the uses of the plant, or that revealed "some particular industry of nature." When its surroundings affected the appearance of a plant, these also were to be indicated. Because the botanical vocabulary of the French language was limited, Dodart warned, academicians would coin words or borrow them from the vernacular.[17]

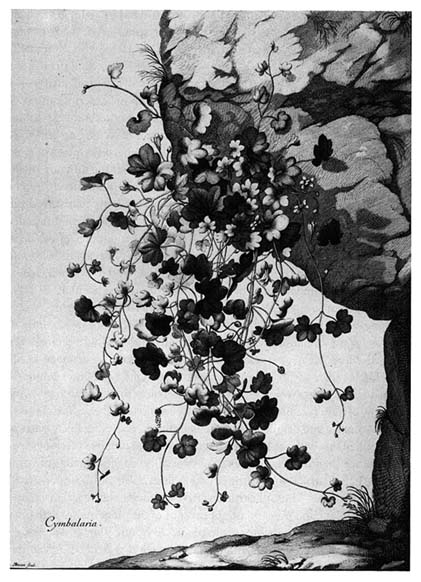

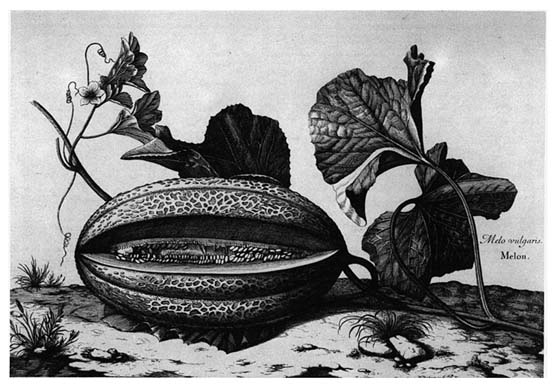

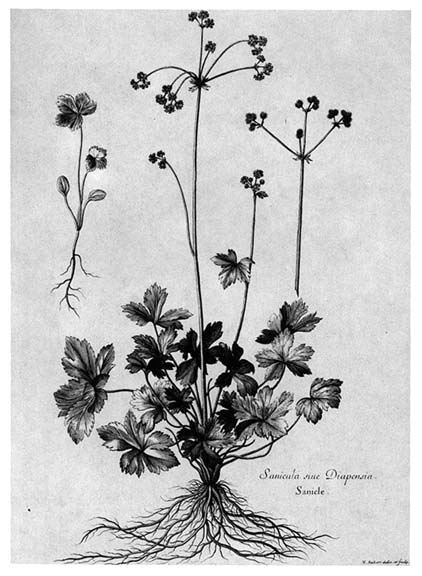

More important, the Academy was now able to commission its own drawings from life. Many of the illustrations in Marchant's Descriptions de quelques plantes nouvelles were copied from the duke's watercolors. But Dodart's Mémoires des plantes announced that the king's patronage would henceforth suffice to obtain engravings of the highest scientific standard; the Academy's artists would refer to the watercolors only if Marchant could not grow certain rare plants. The Academy would take the utmost pains to obtain accurate and detailed pictures. The engravers drew delicate parts or very small plants with the help of a microscope, and they used etchings (eau forte ) rather than line engravings (taille-douce ) to suggest shades of color (figs. 1-12). Instructions to the artists reflected Perrault's and Duclos's recommendations. Thus, illustrations would indicate the actual or relative size of each plant and portray the appearance of the plant in the earth (figs. 3, 4). They would also include a picture of the young plant, "whenever it first appears in a shape different enough to make it difficult to recognize" (fig. 5).[18]

Familiar with his colleagues' views, Dodart adopted them selectively, usually siding with Perrault. He rejected all known systems of classification, washing the Academy's collective hands of the problem that exercised Morison and Ray and whose solution later brought international fame to Tournefort.[19] Dodart shared Perrault's interest in testing methods of propagating plants and wanted to disprove the Theophrastean claim that plants could be propagated from their saps alone. Both Perrault and Dodart also

Fig.3.

Cymbalaria. (From Estampes ; engraved by Bosse;

photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Fig. 4.

Melo vulgaris/Melon. (From Estampes ; engraved by Robert;

photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Fig. 5.

Sanicula, sive Diapensia/Sanicle. (From Estampes ; drawn and

engraved by Robert; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

hoped the Academy could displace superstitions with observations, in that way teaching the public and raising the standard of knowledge about nature.[20]

Despite such similarities of approach and interest, the Mémoires des plantes was in certain respects Dodart's personal statement about the natural history. First, he affirmed the Baconian principle that one should not "condemn as false something that has not succeeded for oneself, but [instead] simply report the methods and results of one's experiments."[21] Dodart presented the Academy's raw findings, without hypotheses or conclusions. Duclos and Perrault, in contrast, expected the natural history to go beyond mere reports of experiment and difficulty. Second, Dodart introduced plant physiology into the natural history by including an explanation of how a plant grew, perhaps as an analogy with natural histories of animals that reported the development of the chick in the egg. He remained purist enough to exclude nutrition or the movement of sap from the natural history, but the cultivation of plants lent itself to analyses of germination and soils.[22] Whether or not Dodart intentionally challenged traditional definitions, no other academician had included these subjects in the natural history.

In ten years four academicians — Huygens, Perrault, Duclos, and Dodart — designed research on plants. They were inspired by earlier natural histories and by a well-established dichotomy between natural history and natural philosophy.[23] As work began in earnest, old distinctions were eroded and the fate of the project was irremediably altered by the addition of chemical analysis. Before considering the effects of that decision, however, the progress of research in all its aspects — cultivation, description, illustration, and chemical analysis — must be reviewed.