The Verisimilar Code

Describing the operation of the verisimilar code in the Biographs presents a more daunting task than describing the histrionic. Because the verisimilar code was intended to mimic reality and create individual characterizations, one cannot turn to mechanical formulations and prescriptions such as are found in the histrionic-code instruction manuals. Nor can one evolve general categories, illustrating each with examples, as with the histrionic code. But the discussion of the theatrical verisimilar code in the previous chapter, in conjunction with the recent work of film scholars, can point to the key characteristics of the verisimilar code in the Biograph films. As we have seen from looking at the verisimilar code in the theatre, byplay and props formed an important part of this performance style. In addition, as Gunning, Thompson, and Staiger have all asserted, use of the face and eyes constituted an extremely important component of the new style of acting in the cinema, which makes sense given the differences between the two media.[6]

The New York Hat (1912) seems a particularly appropriate starting point for the discussion of the verisimilar code, because its inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art's circulating Griffith collection made it quite well known. As one of the few Biographs in common circulation, The New York Hat contributed to Griffith's reputation among film scholars as the originator of "subtle, restrained" acting. It also features Mary Pickford, one of the "Griffith actresses" whom posterity has judged to excel at the new style, and Lionel Barrymore, a Broadway-trained actor in one of his first film roles. Both Barrymore and Pickford have scenes in which the characters' thoughts are revealed through a combination of gesture, expressions, glances, and props, so that we can begin our discussion with a look at two sequences that combine all the key components of the verisimilar code.[7]

Just before her death, Pickford's mother writes a letter requesting that her minister, Barrymore, buy her daughter an occasional gift. Barrymore buys Pickford the fancy New York hat of the title. The town gossips immediately begin to circulate slanderous rumors, and Pickford's harsh father tears up the hat. All ends happily as the misunderstanding is cleared up, and Barrymore and Pickford seem destined for a rosy future.

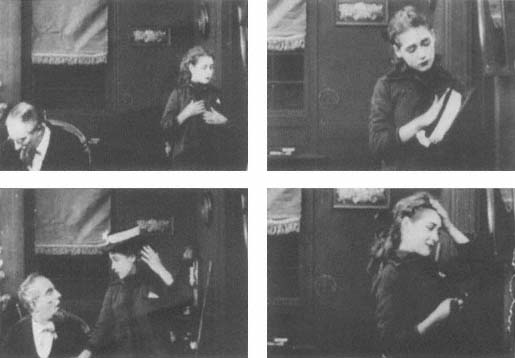

The New York Hat: The verisimilar code.

In the second shot of the film, Barrymore opens the mother's letter and the packet of money that accompanies it. As he reads the letter, his mouth opens in surprise. He picks up the money with a thoughtful expression and looks straight out, almost at the camera, while holding the money. He looks at the letter again and laughs. Placing his hand flat on the desk, he mouths "I'll do it." He nods his head "yes" and looks at the letter again while smiling.

In a four-shot scene, Pickford examines her old hat, decides it won't do, and asks her father for a new one. In the first shot, the standard three-quarter shot of 1912, the father sits at his desk on the left and Pickford stands on the right side of the frame, her right hand at her side and her head slightly tilted as she looks up at a mirror on the wall next to her and straightens her jacket. In a cut to a medium shot, Pickford takes a hat off the wall and brushes off the top with a sad expression. She puts the hat on, examines her reflection, and glances in the direction of her father. An intertitle states, "Daddy, can I have a new hat?" In three-quarter shot again, Pickford stands with one hand out to her father and the other touching her hat, but he gestures her away. In another cut to medium shot, Pickford takes a pair of gloves from a hook near

a mirror, and straightens the mirror. She arranges the gloves in her left hand, smiles, and looks in the mirror. Looking doubtful, she takes the hat off, hangs it up, and shakes her head. Again she looks in the mirror, looks at the gloves, smiles and smooths her hair with her hand. Even without the intertitle, Pickford's performance clearly establishes her character's decision to ask for the hat and her shifting emotions, as she first tries to make do with the old hat and then decides to do the best she can without it.

Although the various elements of the code all work together to externalize mental processes, as in the above example, one can better understand the actual operation of the verisimilar code by isolating, insofar as possible, each component. We start by examining several examples of byplay, the small, realistic touches the actors called "bits of business," which are the performance equivalents of Barthes's realistic effect.[8]

The God Within (1912) with Henry Walthall, Lionel Barrymore, Blanche Sweet, and Claire McDowell, recounts the intertwined fates of two couples. Barrymore seduces Sweet and leaves her pregnant, while Walthall's wife, McDowell, announces to her husband that she too is expecting a child. McDowell dies in childbirth, Sweet's baby is born dead, Sweet acts as a wet nurse to the motherless child, and all turns out well as Walthall and Sweet form a family at the end. The acting of the principals is verisimilarly coded, and all four employ bits of business in their interchanges with other characters.

Near the start of the film, Barrymore comes to tell Sweet that he is leaving town. She sits alone, waiting for him, and when she hears his knock, wipes away her tears, clasps her hands in her lap, and smiles. As they talk, she stands close to him, her hand stroking his lapel, and then leans closer to whisper that she is pregnant. Barrymore rubs the back of his neck in perplexity and then gestures to the door with his thumb. As McDowell tells Walthall that she is pregnant her actions are similar to Sweet's. She takes his sleeve, fingers his collar, puts a hand on his shoulder, and whispers in his ear. When the doctor proposes to Walthall that he take Sweet into his home, Walthall scratches the back of his neck as he thinks. At the film's end, Barrymore comes to Walthall's cabin and proposes to Sweet. Walthall returns home and also proposes to her. Sweet picks Walthall, signaling her decision by taking his hand. The two men converse over the seated woman, and, as they talk, Sweet tilts her head so that her cheek touches her and Walthall's linked hands, the small gesture registering her character's fulfillment and happiness.

These kinds of small gestures can be combined to create the verisimilar equivalent of the gestural soliloquy, in which characters express intense emotions. But while the intent is the same, the nature of the gestures is vastly different. In The Lesser Evil (1911), Blanche Sweet is trapped in a boat's cabin, with only the captain standing between her and a crew of would-be rapists. She stands at the cabin door, hands around the bolt, looking upward and perfectly still except for the slight movement of her hands on the bolt. She

The Lesser Evil: Blanche Sweet fears a fate worse

than death.

then reloads the captain's gun, opens the door to hand him the weapon, then rebolts the door. She leans against the door, her right hand on the bolt and left hand to her face.

The impact of this scene admittedly depends on her expression as well as her gestures, but Biograph actors were fully capable of fulfilling Strindberg's wish that important scenes be acted with the back to the audience. To return to The God Within, Walthall has a gestural soliloquy at his wife's deathbed. His hat in his hand, he looks down at his wife and baby while he raises his hat to his mouth as if to stifle a sob. He turns his back to the camera, showing only about one-quarter of his face in profile, bows his head, and raises his hand to his eyes. After a moment, he turns slightly back, wipes his eyes, looks down again, and kneels at the bedside. He rests his head on his upraised hand while his fingers pull at his hair. Until he kneels, we do not get a good view of his face, and his grief is indicated by posture and hand movements alone.

The byplay in The God Within externalizes thoughts and emotions and delineates character. But "bits of business" could also directly establish character type or create psychological complexity. In The Broken Cross (1911), the residents of a boarding house include a gum-chewing, slovenly servant girl and a hip-swinging, eye-batting manicurist. In The God Within, Barrymore reveals his character's bravado and untrustworthiness by hooking his thumbs in his waistcoat pockets. In A Child's Remorse (1912), Claire McDowell plays a mother described by the Biograph Bulletin as having a "pettish nature."[9] She makes her entrance pushing back her sleeves and smoothing down her dress and then places her hands on her hips, posing for her husband's admiration. When he ignores her, she clenches her fists and gestures to herself as if to say "Look at me!" She then makes a sweeping downward gesture of both hands down the front of her skirt. In Friends (1912), Mary Pickford plays the darling of the mining town whom all the men admire. While awaiting her

The Way of Man: The use of a prop.

beau, she smooths her curls; when he fails to arrive, she stamps her foot impatiently. In the same film, Walthall plays a fastidious prospector-dandy, who returns from the gold fields to see Pickford. Standing at the bar before going up to her, he flicks dust off his sleeves and straightens his cuffs. Earlier, upon unexpectedly encountering an old friend, he had surreptitiously brushed away a tear, an action perhaps not consonant with the dandy image but which adds depth to his character and prepares for his later good-natured renunciation of Pickford.

Byplay also entailed the use of props. In an early example from The Way of Man (1909), Florence Lawrence portrays a woman scarred by an accident who sees her fiancé with another woman. Retreating to the next room, she leans over the back of a chair for a few seconds, her arms straight down the chair back. Then she walks slowly to front center, hands at sides, staring dully ahead. She picks up a hand mirror, looks at her reflection, puts a hand over the mirror, and shakes her head. She then puts a forearm to her forehead. With the exception of the last gesture, Lawrence does not use her customary histrionic gestures but embodies her character's thoughts through body posture, a slight movement of the head, and the look in the mirror. In a scene from The Inner Circle (1912) the use of props augments the fully developed gestural byplay of the verisimilar code. An intertitle, "The Lonely Widower and his child," precedes the film's first shot. A little girl sits in a chair in a tenement room, and her father (Adolphe Lestina) enters. He walks slowly, head bowed, and carries a flower. He looks at the child, smiles slightly, sniffs the flower and turns to look at a picture on a table behind him. His hand barely raised from the table, he extends his bent index finger toward the picture, then rests his hand on the table. The father turns to his child and offers her the flower, but she is sleeping. He straightens, looks at the picture, places the flower in front of it, rests his hands on the table, and looks up, before waking and hugging the child.

The Lesser Evil: Blanche Sweet thinks of her beau.

In this shot the gestures and props develop the portrait of the Lonely Widower announced by the intertitle, but Lestina communicates his sorrow for his dead wife with an upward glance, and his pity for his orphaned child by looking from the picture to her. This brings us to the second important element of the verisimilar code, the use of the eyes and the face. As in Lestina's case, the direction of the look often suffices to convey a character's thoughts (given the narrative context, that is). In another example from Friends , Walthall returns from the gold fields unaware that Barrymore has preempted his place in Pickford's affections. As he and Pickford embrace, he looks over her shoulder to see the picture of Barrymore she has left out. A dawning realization crosses his face, but the mere fact of his seeing the photo indicates that the character's suspicions have been aroused. In Her Father's Pride (1910), Stephanie Long-fellow and Charles West declare their love by look alone. After an intertitle, "The Inevitable," the two look at each other until she bows her head and walks away. His eyes follow her as he smiles. In another sexual interchange based on glances, this time in One Is Business, The Other Crime (1912), we see an early instance of the controlling male gaze that figures so largely in feminist film theory. Edwin August stands at a doorway admiring his wife, Blanche Sweet, who has completed dressing for dinner. His eyes sweep up and down her body as he looks her over, then smiles, and shakes his head as if to say, "You're really something!" She looks shyly away, averting her gaze.

As the trade press would have said, "You can really see the actors think!" Occasionally, the later Biographs devote entire shots to a character's thoughts, with the actors reflecting on the previous action and moving very little if at all. In Friends , after Pickford receives a visit from Barrymore she lets him out and remains motionless, her hand on the doorknob and her eyes moving from side to side. In a similar scene in The Lesser Evil , Blanche Sweet has just gotten a proposal from her longtime beau. She pauses at the front door of her house,

with her hands at her sides and her head down. She looks up slightly, smiles, then goes into the house. Nor is it only women mooning over their sweethearts who pause in reflection. In Friends , the doctor tells Walthall to wait outside while he goes inside to deliver the baby. Walthall stands for a moment with his hand on the doorknob, motionless except for his eyes moving from side to side as he contemplates his wife's fate.

One Is Business, The Other Crime contains an extended instance of the "reflection shot," as the four main characters, a rich couple (Edwin August and Blanche Sweet) and a poor couple (Charles West and Dorothy Bernard) all consider their futures. August has been bribed with a thousand dollars which West, unable to find employment, tries to steal, but Sweet apprehends him, in the process discovering the note offering her husband a bribe. West returns to his wife, and the poor couple thinks about their hopeless lot, while August, in his study, considers Sweet's demand that he return the money, and Sweet, in her bedroom, awaits his decision. In a sequence of eleven shots, the film cuts between Sweet, August, and the poor couple.

1. Sweet walks toward a chair in her bedroom.

2. August fingers the money, starts to put it down on the desk, but instead thrusts it into his pocket.

3. Sweet sits in a chair. She stares ahead, closes her eyes, slumps her head, and rests her arm on a table.

4. West arrives home, sits in a chair by the window, and makes a gesture rejecting something.

5. August takes the money out of his pocket, shakes his head and puts it back, then paces to the rear of the frame.

6. Sweet stands at the back of the frame, arms folded. She drops her hands to her sides, walks forward, yawns, shakes her head, and turns her back, brushing the back of the chair with her hand as she turns.

7. Bernard comes over to sit and talk with West.

8. August turns off the light and sits in a chair by the window, smoking a cigar.

9. West and Bernard sit at the window almost perfectly still.

10. As August sits quietly, "sunrise" illuminates the room. He gets up, takes the money out of his pocket, walks to the desk, and writes a note.

11. Sweet stands, hands on the back of the chair. She looks at the door angrily and exits.

As with the above sequence, many of the "thinking" and "reflection" shots cannot and should not be separated from the editing patterns of which

they are a part, nor, for that matter, from the entire narrative context. This is particularly the case with the reaction shot that reveals mental processes precisely through the accumulation of shots. With the 1911 films, the three-shot—point-of-view pattern began to be standardized, as several films feature sequences in which characters look through windows and then react to what they see, the reaction shot sometimes in closer scale than the rest of the film (The Chief's Daughter, Enoch Arden, His Mother's Scarf, The Two Sides ).