One—

Youth and Student Years

The Tanner's Son from Tapiau

Lovis Corinth once remarked that nature has a way of placing a budding artist in the environment most likely to nurture his creative instincts.[1] He made this statement while reflecting nostalgically on his own childhood, although he was fully aware that the real circumstances of his early years had provided him with little opportunity for artistic growth. Indeed, in a diary entry for May 8, 1925, about two months before his death, he confessed with undisguised regret, "I did not have a good upbringing. In fact, it was one of the worst possible. Those who are brought up better have no idea what effect this has on a child. . . . Not that I want to blame my parents. They did not know any better."[2] There is no question that Corinth's brusque demeanor—frequently offensive to those who did not know him—as well as his continuing self-doubt and his determination to succeed resulted from a childhood that had made him deeply insecure.

Corinth's ancestors, originally perhaps native to the Salzburg region, had settled in East Prussia in the early eighteenth century. They were peasants and artisans in the villages of Lindenau, Moterau, and Neuendorf and in the small town of Tapiau, about twenty miles east of Königsberg. Most of them tilled their own land or operated family workshops. The painter's father, Franz Heinrich Corinth, had grown up to be a farmer. But as the youngest of four sons he had no claim to his parents' property, which, in keeping with local tradition, was to be passed on to his oldest brother. He might have continued working on the family farm had not frictions between the brothers forced him to seek his fortune elsewhere. At eighteen he volunteered for military service and later found employment as secretary to the mayor of Tapiau. Eventually he acquired an estate of his own by marrying a widow. He was twenty-eight years old when he and his cousin Amalie Wilhelmine Opitz exchanged wedding vows on October 2, 1857. The bride was forty-one and the mother of five teenage children. In addition to a sizeable portion of land, she

owned a tannery, much neglected by her first husband but potentially profitable and suitable for expansion. Franz Heinrich soon developed such shrewd insights into the technical and managerial needs of the tanning business that he quickly transformed the shop into a lucrative enterprise.

Amalie Wilhelmine Opitz was the daughter of a prosperous shoemaker from Tapiau. Her first husband, thirty-seven years her senior, had treated her cruelly during eighteen years of marriage, leaving her disillusioned and emotionally withdrawn. After his death the task of raising her children and looking after her property had taught her to be self-reliant. Even in her new marriage she retained absolute control of household affairs and demanded strict obedience from everyone. Franz Heinrich, occupied with supervising the farm and managing the tannery, did not interfere with her domestic regime. Although the relationship between husband and wife was fairly congenial, it too was overshadowed by a conflict that caused Amalie Wilhelmine unending misery and led her to suppress her feelings still further. The sons of her first husband saw Franz Heinrich as an intruder on their property rights and greeted him with malice and hatred. They attacked him physically and even threatened the life of their little stepbrother. "There was no harmony in our house," Corinth wrote in his memoirs. "Besides, everyone was older than I! They were barbarians in the true sense of the word."[3]

Corinth, the only child of Franz Heinrich and Amalie Wilhelmine, was born in Tapiau on July 21, 1858. At his baptism on August 8 in the Protestant church there he was given the names Franz Heinrich Louis, the third name in honor of his paternal grandmother Louise Stiemer; relatives and friends of the family usually called the boy Luke or Lue. Given the tense, awkward relationship between Franz Heinrich and his stepchildren, the development of a close bond between the young father and his own son was inevitable. The father comforted the boy when he was frightened and ill and eagerly ordered a flute from a Königsberg shop when Louis wanted to learn to play a musical instrument. Franz Heinrich hoped that his son would have the university education he himself had been denied. Corinth's mother, in contrast, cared little about the boy's schooling. She was satisfied if he knew how to distinguish the good from the bad and, when necessary, taught him the difference with the aid of a whip. Her hopes for his future centered on the purchase of a small farm, where he could carry on the family tradition without interference from his bickering stepbrothers. Louis often watched his mother as she sat for hours silently spinning or working the loom. There seems to have been little spontaneous communication between the two; only many years later did Corinth understand that when his mother occasionally "forced"

him to hug her, it was because she needed affection.[4] "Deep inside we all felt a great yearning to love," he recalled. "But this love was never allowed to be expressed. Rather, it was hidden out of fear of revealing too much tenderness."[5] Late in his life he acknowledged the pernicious effect on him of such a childhood:

I have been unhappy throughout my life. From the beginning there was the secret war of my stepbrothers against me, a continuous strife and quarrel over the fact that they had received no education. Secretly they even threatened to kill me. The memory of this situation from my childhood has remained with me to this day. I have always felt a certain respect toward the more privileged classes. Yet my disposition did not allow me to love anyone. On the contrary, everyone considered me rather repulsive and crude on account of my ill-bred barbarity. I envied those who possessed a cheerful temperament or greater ability than I. A burning ambition has always tormented me. There has not been a day when I did not curse my life and did not want to terminate it.[6]

Corinth wrote repeatedly about his childhood. His autobiography includes diary entries written when advancing age and political turmoil often gave rise to despair, as indicated by the passage just quoted, as well as recollections of a more lighthearted nature. In addition, he wrote an amusing, partly fictionalized, autobiographical account, Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben . These "legends," first published in 1908, feature one Heinrich Stiemer, a pseudonym for Lovis Corinth. The opening pages of Corinth's Gesammelte Schriften (a compilation of articles, some originally published in Kunst und Künstler, Pan , and several Berlin newspapers), moreover, contain brief recollections of his boyhood in Tapiau. But the Selbstbiographie remains by far the most important source of information on Corinth's family and childhood. The first three chapters deal at length with the painter's youth and years of study. Written between 1912 and 1917, they were apparently planned from the outset for publication. In their careful exposition and stylistic unity they contrast with the later chapters, which retain the form of the diary found in Corinth's desk after his death. Written between November 1918 and May 8, 1925—a time when Corinth, increasingly subject to despondency, questioned the meaning of his life and work—these entries offer an invaluable key to his complex personality.[7]

Corinth's recollections of his childhood are rich in anecdotes and lively descriptions of his parents' home, the barns, the stables, and the tanning pits where bloodstained hides were prepared for processing into leather. We read of animals being slaughtered, their carcasses skinned and broken open, dis-

charging litters of opalescent, steaming entrails. Greedy chickens drink voraciously from pools of blood in the yard adjoining the stables and the tannery. Even when the boy was still too frightened to watch the actual killing, a dead animal held no particular terror for him. Rather it fascinated him like a strange and bizarre toy, as when he once occupied himself by poking the eyes out of the head of a freshly slaughtered pig. Written with the painter's sensitivity for evocative details, these recollections frequently speak of Corinth's intoxication with physical force. Years later, slaughterhouses and butchers' stores continued to interest him. They form part of an iconography of aggression and violence found throughout his oeuvre.

Beyond the stables and workshops as well as in them Louis found much to marvel at. The Corinth home stood near the divergence of the river Deime from the mightier Pregel, where the latter continues its separate course to the Baltic Sea. There Louis watched steamers carrying travelers to and from the seashore and slow-moving Lithuanian onion barges on their way to the Königsberg market. Yet nothing pleased him more than to spend his time cutting silhouettes from paper and making caricatures. Friedrich Wilhelm Bekmann, an elderly carpenter who frequently helped Corinth's father with chores, had taught him how to draw all sorts of animals and human figures, and Corinth fondly remembered the old man many years later as his "first teacher in art."[8] Another friend, Emilie, the one-eyed daughter of one of the women supervisors employed in the state prison located in the remains of an old castle across the river, lived with her mother upstairs in the Corinth home. Emilie sometimes unrolled for Louis a carefully guarded family treasure, a reproduction of the equestrian statue of King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia, and told him of the monument that stood on the parade grounds in Königsberg. Emilie, according to Corinth, first aroused in him a love for pictures, and he began to examine the crudely painted allegories on the target disks that some of his parents' friends and relatives had won at shooting matches in the nearby village of Wehlau and displayed proudly in their homes. He also admired the frescoes on the vaulted ceiling of the Tapiau church, which filled him with awe. Once he even had the good fortune to watch a painter at work on a landscape study by the river.

When Louis was not yet six, in the spring of 1864, he went to school in the one-room schoolhouse in Tapiau. He quickly learned to read and write, but arithmetic never ceased to confound him. Despite supplementary lessons, he had to repeat one class. Corinth's father remained nonetheless determined that his son receive the training required for university study and at Easter

1867 took the nine-year-old to Königsberg and enrolled him at the Kneiphöfisches Gymnasium.

Except for summer vacations, which he spent in Tapiau, Corinth lived for the next seven years with his mother's sister. His aunt, the widow of a shoemaker, was avaricious, aggressive, and crude. Although Corinth learned to appreciate her sarcastic humor, he despised her character. Since she was more interested in having Louis chop wood and attend to other menial chores than in having him memorize Greek and Latin, his scholastic performance left much to be desired. Although the school authorities suggested repeatedly to Corinth's father that he change the boy's environment, the advice, strangely enough, went unheeded. The dichotomy between Louis's home life and his life in school set him apart from his refined and well-groomed fellow students, who from the very beginning laughed at his pronounced East Prussian dialect. Although he soon forced himself to speak only High German, he remained an outsider, masking his insecurity with sullen and aggressive behavior. Without the companionship of friends and caring relatives, he devoted most of his free time to drawing. This was also the only subject in which he excelled at school.

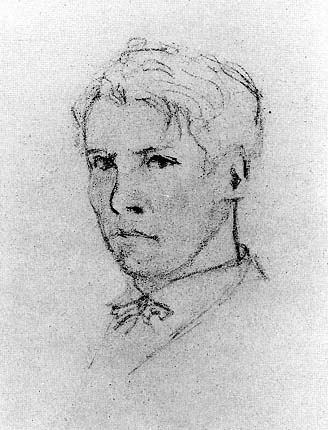

Some of his earliest drawings still survive. They include a caricature of one of his teachers supervising the boys in the rainy schoolyard and other drawings inspired by lessons in ancient history and illustrations in his school-books. Awkward and crude, these drawings hardly indicate a precocious talent. As an adult, however, Corinth cherished these juvenilia. They largely escaped his self-critical destruction of many of his student works and other early paintings. Evidently wishing to document the genesis of his creative activity, he preserved many and as late as 1915, at the height of his career, gave one of them, a drawing illustrating the death of Alexander the Great, to his then eleven-year-old son Thomas as a Christmas gift.[9] One early drawing stands out for its superior conception and execution. This is a self-portrait (Fig. 1) done sometime in 1873, when Corinth was either fourteen or fifteen.[10] Relying primarily on contours and a few skillfully placed accents to define such details as the nose and eyes, Corinth seems to have captured his likeness with deceptive ease. The features are close to the picture surface and dominated by the apprehensive yet challenging gaze. The look is that of a youth who knows doubts but is sustained by stubborn resolution. Perhaps the death of Corinth's mother on April 6, 1873, helps to account for the serious expression. At any rate, this self-portrait marks the beginning of a fascination with his own image that was to persist throughout Corinth's career,

Figure 1

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1873. Pencil, 8.9 × 7.6 cm.

Private collection.

frequently prompted by an event of some autobiographical importance. With the possible exception of Rembrandt, Max Beckmann, and Egon Schiele, no other artist has been so fascinated with his own image.[11]

In the spring of 1876, having taken eight years to complete six grades at the Kneiphöfisches Gymnasium, Corinth asked his father's permission to leave school three years prior to his expected graduation and enroll in the Königsberg Academy instead. Franz Heinrich was disappointed, but his kindness did not permit him to interfere with his son's own plans for the future.

By the time Corinth was admitted to the Königsberg Academy, at Easter 1876, the circumstances of his life had changed markedly. Following the death

of his wife, Franz Heinrich Corinth sold the property in Tapiau, paid his stepchildren their share of their mother's estate, and invested the remaining, still substantial, capital in a number of houses in Königsberg. He himself moved to the city in 1876, sharing with Louis a spacious and pleasantly furnished apartment at Tragheimer Pulverstrasse 25. Henceforth he was to take an avid interest in his son's career, supporting him generously and encouraging him in every way possible.

At the Königsberg Academy

As might be expected in a provincial capital as remote as Königsberg, the artistic milieu was undistinguished. The municipal painting gallery featured copies after Italian and Netherlandish masters from the fourteenth through the seventeenth century, on loan from the royal painting gallery in Berlin, and a small group of German, Flemish, and Dutch works—including paintings attributed to Holbein, Brouwer, and Frans Hals—that had been left to the city by a former mayor, Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel.[12] The gallery's contemporary art reflected the taste and discretion of members of the Königsberg Artists' Association. Since 1833 this organization had sponsored the biennial exhibitions at the Königsberg Castle and was responsible for acquiring modern paintings for the gallery's permanent collection. The works purchased over the years were mostly history and genre paintings, including pictures by Paul Delaroche, Ary Scheffer, Karl von Piloty, and Franz von Defregger. Since the 1870s the municipal gallery had been housed in the art academy, and the collection served as a convenient supplement to studio instruction.

The academy itself was founded in 1842 by order of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, replacing a drawing school that had been in operation since 1790, superintended by the academy in Berlin.[13] The teaching program of this drawing school was based on that of the private Parisian ateliers: students began by copying engravings and reproductions of drawings and then proceeded to drawing, first from plaster casts and, finally, from the live model. Anatomy, geometry, and perspective were also taught. This was still the curriculum (augmented only by instruction in painting) when Corinth attended.

Unfortunately, the full extent of Corinth's activity during his years at the Königsberg Academy cannot be known because he destroyed so many of his early works. "Nobody thinks of buying these crazy products of a young man, or . . . of accepting them as gifts," he wrote in 1917 in a letter to Alexander Koch, the editor of Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration .[14] Thus no drawings or paintings of the nude model from this time have come to light. And there is little

additional evidence of what may be called student work in the strict sense of the term, since all of Corinth's paintings and most of the drawings that have survived from this time originated outside the classroom. They indicate at best that Corinth was a serious student who applied himself diligently and soon developed a keen power of observation.

Corinth's memoirs, similarly dominated by accounts of extracurricular activities, reveal nothing of his attitude toward the teaching program at the academy. He later remembered his years there as the happiest of his youth, largely because he discovered then the joys of a harmonious home life and found friends who knew how to surmount his habitual reserve. "No student was considered competent," he wrote, "unless he was also a notorious drinker. We soon developed great mastery in the consumption of alcohol. . . . All my new friends drank . . . until we could no longer tell which one of us could hold the most."[15] While at the academy Corinth set a pattern of social behavior he would follow in his early adult life.

Relations among the teachers at the academy were less congenial than those among the students. Because the school lacked effective leadership, petty rivalries among the faculty developed into bitter intrigues. The academy's first director, the history painter Ludwig Rosenfelder, had retired in 1874 after more than thirty years of service, and Max Schmidt, a landscape painter who had previously taught at the Weimar Academy, was temporarily entrusted with administering the school. For six long years, however, the Prussian Ministry of Education was unable to decide on a permanent successor to Rosenfelder. Meanwhile, the various faculty members hoping to be appointed to the vacant post regarded one another with suspicion.

Corinth's first teacher at the academy was Robert Trossin (1820–1896), a pedantic copper engraver well known for meticulously reproducing paintings by Van Dyck, Guido Reni, and Murillo as well as several contemporary masters. He taught the antiquated method of drawing after model books by Bernard Romain-Julien, the French painter and lithographer, and lithographs by Josef Kriehuber, the Viennese portraitist. Corinth remembered Trossin as patient and tenacious:

"Not too pitchy!" That was his favorite expression whenever a student had used too much black chalk. Trossin was a member of the old guard, . . . it was said that he could even boast of having been awarded a Russian medal. He had engraved Guido Reni's Mater dolorosa , and legend had it that copying the figure's neck alone had taken many months of hard work.[16]

Figure 2

Lovis Corinth, Carousing Lansquenets , 1876.

Pen, 18.4 × 24.1 cm. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1957/224).

Johannes Heydeck (1835–1910), one of Rosenfelder's former students, taught drawing after plaster casts and the live model as well as painting. Like his teacher, Heydeck specialized in history paintings in the manner of Louis Gallait and Edouard de Bièfve, Antwerp painters whose works were first shown in Germany in 1842 to unprecedented acclaim. Corinth was enthralled by the extravagant staging and rhetoric of such compositions and by the care lavished on the smallest detail. He particularly admired Rosenfelder's chef d'oeuvre in the Königsberg municipal painting gallery, The Surrender of Marienburg Castle to the Mercenary Captains of the Teutonic Order in 1457 (1857; present whereabouts unknown): "Suits of armor, flowing robes, velvet draperies, and the way the Grand Master holds the key to the fortress in his veined hand. . . . these were my motifs around 1876."[17]

Carousing Lansquenets (Fig. 2), a pen-and-ink drawing, testifies to Corinth's early enthusiasm for historical subjects. Although the date and signature were added much later, the drawing was apparently done soon after Corinth began his studies at the academy. The faulty anatomy of the figures indicates

Figure 3

Otto Edmund Günther, The Gambler , 1872.

Oil on canvas, 40.8 × 48.0 cm.

Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar.

a lack of experience in life drawing; the hatchings and crosshatchings, painstakingly applied, are a legacy, no doubt, of Trossin's copying method.

Corinth's plans to become a history painter in the tradition of Rosenfelder were short-lived, however, for his interest was soon given a new direction by Otto Edmund Günther (1838–1884), a graduate of the academies of Düsseldorf and Weimar who joined the Königsberg faculty in 1876. Günther's early works include a number of historical compositions, but he had long since turned to genre painting, deriving his subject matter almost exclusively from the everyday life of Thuringian peasants. He was especially fond of themes that allowed him to explore anecdotal byplay and frequently applied the melodramatic rhetoric of history painting to such situations as the one he depicted in The Gambler (Fig. 3). In this painting a young peasant woman has come with her infant to the inn to fetch her husband, who has just lost at cards. The conception and general composition of the painting recall works by Ludwig Knaus and Benjamin Vautier, Düsseldorf artists who practiced a similar ethnographic genre. Although Günther's tonal palette differs from the lively colorism of Knaus and Vautier, the meticulous still-life elements in the picture are yet another legacy of the Düsseldorf school.

In Königsberg, Günther was originally appointed to teach painting, but he soon assumed responsibility for some of the advanced drawing classes as well. He was the youngest member of the faculty, and his approach differed markedly from that of his colleagues. Seeking to expand the experience of his students beyond the confines of the academy's curriculum, he founded a junior artists' association, where they could work independently, exchange ideas, and engage in mutual criticism. He also encouraged them to work as much as possible out-of-doors and to heighten their visual perception in a familiar milieu by choosing subjects in the Königsberg market and the harbor. Corinth's memoirs include a vivid account of the mornings he spent in the slaughterhouse by the river Pregel. There he sketched and painted, oblivious to the pushing and shoving of the butchers and the sounds of the animals collapsing beneath cracking axes, his eyes fixed firmly on the movements of the men and on the colors: the reds and fatty whites of raw meat and the purple, shot through with glistening mother-of-pearl, of the entrails hanging in clusters from iron posts.[18] Günther's informal teaching method and easy-going manner appealed to Corinth: "For me Günther was an excellent teacher. Even more important, he was like a fatherly friend. Clever and sparkling with wit, he drew me, the awkward and suspicious youth, close to him."[19]

Not surprisingly, Günther had a profound effect on Corinth's early development, both directly and indirectly. In the summer of 1876 he persuaded Corinth and several other students to travel to Thuringia, where he introduced them to some of the leading painters of the Weimar school, including the aged Friedrich Preller, who in his youth had enjoyed the support of Goethe. A visit to the studio of the landscape painter Karl Buchholz, a quiet, introspective man, impressed Corinth, who called him "the genius of that Weimar period." Corinth remembered seeing in Buchholz's studio many of the small pictures contemporary critics had praised as depictions of nature "in her morning gown."[20] Buchholz's landscapes of the 1870s are indeed poetic, though faithful, descriptions of the Thuringian countryside, their basic structure unvarying. The artist rarely, and then only sparingly, introduced human figures into his landscapes, although he usually implied human presence with a pictorial space that seems to adjoin the viewer's own. One of the landscape drawings Corinth made during his journey through Thuringia (Fig. 4) is similar in conception and evidently bears more than an accidental resemblance to Buchholz's quiet pictures. Technically the drawing is superior to the contemporary figure composition in Hamburg (see Fig. 2). Corinth's attention to the details of the half-timbered houses is matched by his care in observing the boulders in the foreground and the masonry of the bridge. The bridge leads

Figure 4

Lovis Corinth, In Thuringia , 1876. Pencil,

26 × 36 cm. Private Collection.

Photo courtesy Bernd Schultz.

Figure 5

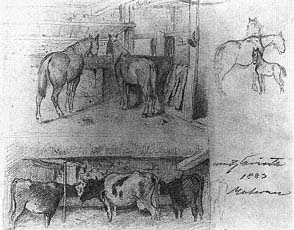

Lovis Corinth, The Barn , 1879. Pencil, 19.5 × 27.3 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.,

Rosenwald Collection (B-19562).

Figure 6

Lovis Corinth, Kitchen Interior , 1880. Pencil, 27.0 × 31.7 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.,

Rosenwald Collection (B-19567).

toward a compositional center that is reinforced by the shadow under the roof at the left and the repeated diagonal roof lines on the right. The careful execution suggests that the drawing may have been intended for one of the academy-sponsored competitions usually held at Christmas time, when outstanding portrait and figure studies and landscape drawings were selected for special awards.

Other works from Corinth's early student years are more specifically indebted to Günther's example. It did not take much persuasion to make the budding artist seek his inspiration in the East Prussian countryside, familiar as he was with the life and customs of the local peasants. He drew two barn interiors (Fig. 5), one occupied by horses, the other by cows, during a visit to his aunt and uncle's farm in Moterau in 1879. The signature and the incorrect date of 1883 are later additions; the lower half of the drawing was in fact a study for a small painting of a cow barn (B.-C. 2) dated 1879. Kitchen Interior (Fig. 6), drawn the following year when Corinth was back in Moterau painting portraits of his uncle and aunt (B.-C. 5, 6), like The Barn , lacks spontaneity. The awkwardly diffident style of both drawings typifies this stage in Corinth's development. The individual objects and forms are cautiously circumscribed by reinforced contours; hatching and crosshatching indicate modeling. Delicate modulations, partly exploring the grainy texture of the paper, unify the composition, whose pervasive tonality resembles that of Günther's

Figure 7

Lovis Corinth, Seated Peasant and

Other Sketches , 1877. Pencil, 26.1 × 20.0 cm.

National Gallery of Art, Washington,

D.C., Rosenwald Collection (B-19571).

dusky interiors. The drawing of a seated peasant (Fig. 7), dated June 26, 1877, more specifically suggests the figures that inhabit Günther's genre paintings. Here the fastidious drawing method is evident in the repeated sketches of the hands and in the portrait sketch in the upper center of the sheet, where the textures of hat, face, and shirt collar are all carefully distinguished.

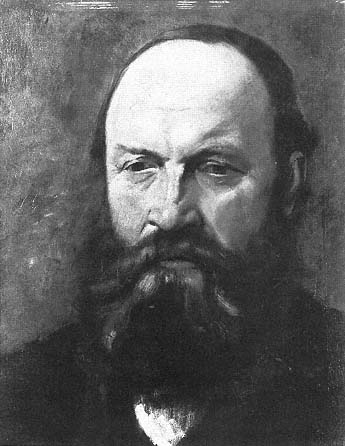

The same attention to detail is found in the few paintings that survive from Corinth's years at the Königsberg Academy. They consist of a forest interior (B.-C. 1) conceived in the manner of Buchholz, the Cow Barn (B.-C. 2) already mentioned, and four portraits, including the ones he painted of his uncle and aunt in Moterau—all from the last two years at the academy. The small painting in Hamburg of an unidentified man (Fig. 8) exemplifies these early studies in oil. The averted gaze and inanimate expression indicate that Corinth grasped the sitter's image primarily in its characteristic form and appearance; the extreme close-up view allowed him to explore physiognomic details fully. The modeling is smooth and reveals a thorough understanding of the interaction of facial muscles and bone structure.

Figure 8

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of a Man , 1879. Oil on canvas on panel,

39.5 × 31.0 cm, B.-C. 3. HamburgerKunsthalle, Hamburg (2630).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

Corinth's studies in Königsberg ended abruptly in the spring of 1880 when Günther resigned from the academy. From the beginning Günther's popularity had irritated his colleagues, and as his following continued to grow, they accused him of catering to the school's best students to gain the coveted position of academy director. Rather than endure such strife, he decided to return to the Weimar Academy, but not without assuring his devoted students of the best possible further training. Some followed him to Weimar; others went to Berlin. Corinth, on Günther's recommendation, was admitted to the studio of the celebrated Franz von Defregger at the academy in Munich.

At the Munich Academy

The walls of Munich are covered with frescoes as with wallpaper upon which are painted red, blue, green, yellow, and rose-colored robes, . . . silk stockings, riding boots, and doublets. Here is king who takes an oath, there is a king who abdicates, and still another who signs a treaty, . . . this one gets married, that one dies. . . . And sculpture! It is unbelievable! One can easily count three thousand statues in the city. They all look alike. . . . [But] the young people of Munich amount to something. This is why I stayed so long. They are firmly determined to let go of the old bric-a-brac, and I have seen young painters spit when the conversation turned to the so-called princes of German art.[21]

Thus Gustave Courbet, in a letter to his friend Castagnary dated November 20, 1869, summed up his impressions of the Bavarian capital. The French painter had just returned from the city's first major international exhibition, which included some of his paintings along with those of Manet, Corot, and several leading exponents of the Barbizon school. Despite the widespread criticism of the "social" implications of his picture The Stonebreakers (1849; formerly Staatliche Gemäldesammlungen, Dresden), he was awarded Munich's highest distinction, the Order of Saint Michael First Class. Considering that the exhibition included nearly 4,500 works from all parts of Europe, Courbet's success was no mean feat and remains a credit to the perceptive jury. That he could both mock Munich as a stronghold of history painting and gain recognition there for his achievement indicates how the 1869 exhibition pitted opposing tendencies against each other: the dazzling historical reconstructions typical of Piloty and his followers and the visual immediacy that distinguishes not only Courbet's work but also the candid pictures of Wilhelm Leibl, whose sensitive Portrait of Frau Gedon (1868–1869; Staatliche Gemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) was included in the show. In its execution Leibl's picture resembles contemporary paintings by Manet. Yet Courbet, who considered this portrait the best German work in the entire exhibition, was no doubt thinking of Leibl when he wrote to his parents, "The young people [of Munich] paint exactly the way I do."[22]

The development of German and specifically Munich painting might have been radically altered had there been an immediate sequel to the exhibition. For there is no question that by 1869 Paris and Barbizon had seriously challenged Rome as the mecca for German painters. Between 1760 and 1840 more than three hundred German artists had studied in the French capital.[23] Although most were from Berlin, the Bavarian contingent had increased stead-

ily since about 1815. Just prior to 1869 the Munich landscape painter Adolf Lier worked with Jules Dupré, and in 1868 Hans Thoma and Otto Scholderer were in touch with the Barbizon painters and Courbet. Henri Fantin-Latour paid special homage to Scholderer when he included him among Manet's friends in the historic group portrait A Studio in the Batignolles Quarter (1870; Musée d'Orsay [Galeries du Jeu de Paume], Paris). Leibl, who formed a close friendship with Courbet during the 1869 exhibition, also accepted an invitation from the painter Henriette Browne (Sophie de Saux) to visit Paris in November of the same year. Unfortunately, the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War forced him to return home after only nine months. Many years were to pass before a similarly congenial exchange between artists of the two countries could be resumed.

The art-loving public, even after the 1869 exhibition, continued to prefer historical concoctions to works based on direct experience. Purely pictorial problems like those emphasized by Leibl elicited little interest during the "Gründerzeit," or boom period, of the 1870s and 1880s. Far more popular were the spectacular works by Piloty and the Austrian Hans Makart, whose name has become especially associated with these vainglorious years. He and his friends Franz von Lenbach and Friedrich August von Kaulbach enjoyed unprecedented financial success while Leibl and the painters of his circle had little following. Indeed, Leibl left Munich in 1873 and spent the rest of his life in the small villages of Upper Bavaria.

When Corinth arrived in Munich, painting there was dominated by two trends. The retrospective tendencies of the Piloty school were vigorously championed by Lenbach while many younger artists followed the painters in Wilhelm von Diez's circle. Lenbach's worship of gallery tones and his stereotyping of chiaroscuro effects borrowed from Titian, Rembrandt, Velázquez, and Van Dyck made him the natural spokesman for reaction. Diez, though not especially innovative himself, encouraged his students to become independent. Largely self-taught, he was an outstanding draftsman and illustrator in the tradition of Adolph von Menzel and a fervent admirer of the Dutch genre painters of the seventeenth century, whose works he had studied in the Alte Pinakothek. The narrative talent that made him a fine illustrator also determined his choice of motifs as a painter. Diez is still best known for his scenes from the time of the Thirty Years' War and the wars of the French Revolution. But his paintings, unlike Piloty's elaborate historical reconstructions, celebrate the unsung heroes on the periphery of the action, boisterous freebooters, camp followers, and peasants. Diez's studio, the most popular at the Munich Academy, attracted men as dissimilar in talent and temperament

as Leibl's friend Wilhelm Trübner; Max Slevogt; Fritz Mackensen, who later helped to found the Worpswede painters' colony; and the future theorist of the Dachau school, Adolf Hölzel, who eventually became one of the most important teachers of twentieth-century German art.

Franz von Defregger (1835–1921), whom Günther had suggested as Corinth's next teacher, had been Piloty's student and continued to work in the spirit of the aging but still influential master. He was especially famous for a type of "historical" genre painting he himself had invented. His earliest work in that genre—the one that originally established his reputation—is Speckbacher and His Son Anderl (Museum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck), painted in 1869, the first in a series of pictures illustrating episodes from the Tyrolean Peasant Wars of Liberation of 1808–1810. When Corinth came to study with him in the summer of 1880, Defregger was hard at work on The Storming of the Red Tower (1881; Staatliche Gemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich), a lively multifigure composition depicting an event from the War of the Spanish Succession of 1701–1714. Besides these historical subjects Defregger also painted a great deal of peasant genre, idealized pictures of life in the villages of his native Tyrol that have much charm and a folksy wholesomeness that suggests none of the drudgery and hardship of everyday rural existence. His romanticized conceptions, with their lively characterizations and authentic milieus, made him the most popular peasant painter in Munich in the 1880s and 1890s.

Corinth had become familiar with the range of Defregger's work in Königsberg, where the municipal gallery owned one of Defregger's pictures of Tyrolean poachers and, in 1879, had acquired a major painting from the Tyrolean Peasant Wars cycle, Andreas Hofer on the Way to His Execution (1878). Defregger was clearly well suited to rekindle Corinth's love for history painting without disturbing the reverence for nature that Günther had fostered in his students, and Günther's suggestion that Corinth continue his studies with the Munich painter must have seemed logical.

As it turned out, however, Defregger thought Corinth needed more experience in painting and suggested he make up the deficiency elsewhere. Thus Corinth remained in Defregger's studio for less than six months, entering the atelier of Ludwig von Löfftz (1845–1910), another much-sought-after teacher at the Munich Academy and one of Wilhelm von Diez's former students, in October 1880. For his own pleasure Löfftz painted fresh and spontaneous landscapes and interiors. In public showpieces like Christ Lamented by the Magdalene (Fig. 9), on which he labored for five years, however, he concentrated on meticulous modeling. In his teaching, too, he emphasized the accurate repro-

duction of each nuance of light and shade, usually to the detriment of color. According to Corinth, the models in Löfftz's studio were expected to pose for months on end:

Especially favored were old models or those who no longer had any fresh skin tones. "Ruins of mankind," we used to call them. We scrutinized their faces and tried to render them in shades of grayish green. We called such works "good in tone." Löfftz came and gave his approval whenever a student had worked in his beloved manner. "Very good in tone," he would say, or "two more years with me, and you will be an artist."[24]

Corinth painted two portrait studies of old women (B.-C. 7, 8) in this context in 1882. His recollections are corroborated by Karl Stauffer-Bern, a Swiss who studied with Löfftz in 1879 and 1880. Stauffer-Bern criticized Löfftz's excessive emphasis on modeling in a letter to his parents, March 20, 1880:

One gets somewhat intimidated by this and does not dare to make a spontaneous effort. . . . Surely, it also has an advantage, since one learns to pay very close attention to modeling, which otherwise is often neglected. Still, I believe that color should not be passed over lightly. In my study of that woman I was well on my way to losing the color altogether as I continually subdued the tone toward gray.[25]

Löfftz apparently demanded strict discipline and accepted only students who convinced him of their commitment to their work. Stauffer-Bern praised Löfftz as a dedicated teacher:

Each time he corrects, one can tell that one has learned something. . . . He completely sacrifices himself for his students, and I think his efforts are not wasted. We will hardly ever finish that nude, but I believe that we have learned a great deal by working on it and that once again we have made considerable progress.[26]

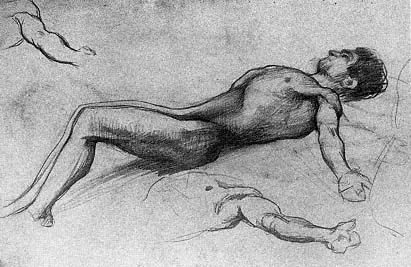

The nude that Stauffer-Bern referred to was a "crucified Christ" on which he and his fellow students worked "relentlessly."[27] Three drawings in an early sketchbook by Corinth, preserved in Kiel, suggest how common such an assignment was in Löfftz's studio: one is a nude Saint Sebastian, his upraised hands fastened to a tree; the others are "crucified" male nudes, one a preliminary study for the 1883 painting Crucified Thief (Fig. 10). The drawing,

Figure 9

Ludwig von Löfftz, Christ Lamented by the Magdalene , 1883.

Oil on canvas, 114.7 × 191.5 cm. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen,

Neue Pinakothek, Munich (7723).

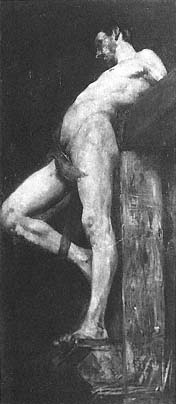

Figure 10

Lovis Corinth, Crucified Thief ,

1883. Oil on canvas,

180 × 80 cm, B.-C. 10.

Private collection, Bochum.

an example of the mise en place of French ateliers, typifies the clarifying life studies by nineteenth-century art students, who tried to unify human anatomy with a "line of action."[28] That Corinth's project originated in the classroom is even more evident in the painting than in the drawing. The complicated posture, particularly difficult to render in a foreshortened close-up seen from below, was clearly intended to present the student with pictorial problems to master in a life-size format; the theme itself was unimportant. The religious title was merely that suggested by the model's pose. Corinth painted the figure exactly as he saw it, including such awkward studio props as the footrest and the supporting strap around the right leg. Set off against the dark, opaque ground, the flesh parts are carefully modeled so as to register the slightest gradations of light and shade.

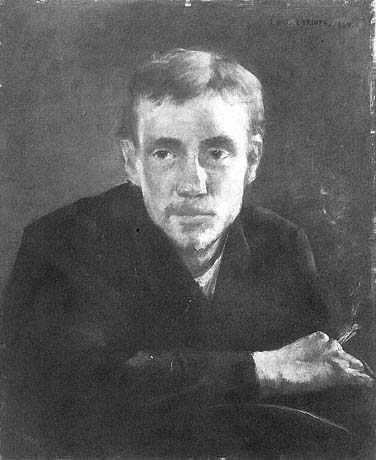

Löfftz's influence is also evident in the portrait Corinth painted of his father (see Plate 1) during a visit to Munich. Nearly life-size, it is the earliest large-scale portrait by Corinth that has survived. Touches of color, sparingly applied, enliven the pervasive grayish brown tonality of the picture. The modeling carefully explores the texture of the face and hands. There are technical flaws, such as the sitter's awkward position, which flattens him, and his unresolved relation to his surroundings. He sits not in a defined space but in front of an undifferentiated pictorial ground. Corinth's superior conception, however, more than compensates for these weaknesses, setting this painting apart from his earlier portrait studies. His attention to texture, here extended to the wineglass and rose on the corner of the table, speaks of efforts to render the characteristic material manifestation of each form. But it is also evident that the harmonious relationship between father and son and their mutual trust allowed the young painter to temper his fastidious technique with empathy. Franz Heinrich's physical proximity to the picture surface suggests a correspondingly close spiritual accord between father and son. His relaxed posture and patient expression testify to the love and confidence the two men shared.

That Corinth responded most empathetically to sitters he knew is confirmed by the eloquent self-portrait drawing of 1882 (Fig. 11). The drawing is surprising from a technical point of view, for it anticipates the forceful manipulation of the graphic medium that became typical of Corinth's more mature work; it is also his first self-portrait to emphasize keen characterization over physiognomic truth. The rugged features, for instance, belie Corinth's youth: he was no more than twenty-four years old when he made the drawing. The face rises darkly from a broad base of erratic lines that rapidly circumscribe the sketchbook, hand, and shoulders. The uneven hatchings ac-

Figure 11

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1882. Crayon, 30.9 × 25.9 cm.

Staatliche Museen, Berlin (DDR) (36/946).

centuate the forms revealed by the harsh light illuminating the face from the left. As in the self-portrait from 1873 (see Fig. 1), Corinth commands the viewer's attention by the sheer force of his gaze. Yet the glowering stare reveals an impassioned defiance only implied in the earlier drawing, in which the fastidiously groomed youth looks at us with vigilant apprehension. Corinth drew the later self-portrait as if in a state of barely contained agitation, with his hair and beard disheveled and unkempt. In none of his earlier works had he achieved a comparable unity of expressive content and form. Many years later Corinth would tell his own students that the artist's "passion to get to know himself . . . makes the self-portrait the favored means of study of any painter."[29] His own predilection for self-analysis explains why the 1882 self-portrait is one of his most independent and revealing works.

No other work from Corinth's student years in Munich shows the same freedom from academic conventions as this self-portrait. Indeed, Corinth remained largely untouched by trends outside the academy. For example, although he knew Wilhelm Trübner's paintings from the weekly exhibitions sponsored by the Munich Artists' Association in the Hofgarten arcades, Trübner's rich colorism and lively brushwork made no impression on him. If anything, as he later admitted, Trübner's work thoroughly bewildered him at this time.[30] He was certainly familiar with plein air paintings by Max Liebermann and Fritz von Uhde, for both artists were represented by major works at the international exhibition held at the Munich Glass Palace in 1883. The two outdoor scenes that Corinth painted the same year (B.-C. 15, 16), however, constitute no more than a minor effort to become engaged in similar pictorial problems. Instead, he admired Georges Rochegrosse's vividly depicted slaying of the Roman emperor Aulus Vitellius (1882; Musée Municipal, Sens), which was also included in the 1883 exhibition. And he borrowed outright the melancholy chiaroscuro of Jozef Israëls's The Widower (1880; Rijksmuseum H. W. Mesdag, The Hague) along with Löfftz's tonal manner when he painted The Conspiracy (Fig. 12) in 1884, emphasizing the descriptive and expressive function of the light that enters the dusky room through cracks in the shutter. The painting is highly ambitious not only in scale but also in Corinth's mastery of the pictorial space. Unlike the figures in Corinth's earlier portraits, the three men in the 1884 painting occupy a defined interior. Corinth's sense that one of his chief tasks in painting the picture was to articulate the interior space is evident from the calculated means he used to achieve this goal: reinforced by the repoussoir of the large dog in the foreground, the four chairs, standing at right angles to each other, serve as the primary space-defining

Figure 12

Lovis Corinth, The Conspiracy , 1884. Oil on canvas,

150 × 110 cm, B.-C. 17. Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Bruckmann, Munich.

elements. Apparently Corinth invested the painting with a specific anecdotal content only after completing it. In short, like the Crucified Thief of the preceding year, The Conspiracy , originally entitled "The Black Plot," is still a typical student work. Nonetheless, Corinth was sufficiently satisfied with it to send it to London for exhibition.

Antwerp

Early in 1884 Corinth's relationship with Löfftz seems to have deteriorated, and Corinth hurried to leave Munich. Initially he thought of going to Paris, but he dreaded the French hostility toward German visitors that followed the Franco-Prussian War. Rumor had it that a German artist wishing to get ahead in Paris would do well to deny his nationality.[31] This rumor is confirmed by the somewhat earlier experience of Max Liebermann, who lived in Paris and Barbizon from 1873 to 1878. Liebermann had a studio in Montmartre in the building where Viscount Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic—perhaps best known from Edgar Degas's 1873 painting of him and his two daughters—also had an atelier. Lepic wanted to introduce Liebermann to several French painters, including Edouard Manet, but was forced to abandon his plans when these painters resisted even the suggestion that they might share a café table with the German. Liebermann had arrived in Paris with two letters of introduction, one addressed to the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens, the other to Léon Bonnat. Bonnat received him coolly and on a second visit, only slightly more gracious, advised him bluntly: "Make the small sacrifice of having yourself naturalized, and you will be one of us." Ignoring the suggestion, Liebermann nonetheless managed to exhibit regularly at the Salon from 1874 onward, though a critic that year commented angrily that in return for the privilege the painter should have relinquished his German citizenship. To this critic it seemed "a crime to perform Richard Wagner in France and to admit Prussians to our exhibitions." As late as 1882, Liebermann, having joined the Cercle des XV, avoided its meetings so as not to provoke hostile sentiments.[32]

Against this background it is perhaps not surprising that Corinth decided instead to go to Antwerp. Some of his friends in Munich had suggested that once there, he should get in touch with a young Belgian painter named Paul Eugène Gorge. Little is known about Corinth's sojourn in Antwerp, and it seems that in later years he did not even want to be reminded of the experience. He writes in his autobiography that he came to dislike the city after about three months and found the people he met through Gorge incompatible—probably because "they belonged to a different nation," and "the genuine East Prussian simply does not mix with strangers."[33] Only for Gorge did he reserve a special word of praise, calling him a man of "charm and pure character."[34]

Paul Eugène Gorge (1856–1941), a graduate of the Antwerp Academy, was affiliated with the artists' group Als Ik Kan, founded in October 1883 by a number of Antwerp painters, including the young Henry van de Velde. Con-

ceived as an artists' cooperative to further opportunities in the art market, Als Ik Kan was not avant-garde but conservative and traditional in outlook, as the group's name, taken from Jan van Eyck's famous motto, implies.[35] Gorge, for instance, about whom little else is known, painted landscapes and interiors in soft grayish tones. His work shows the influence of Charles Mertens's early paintings, which reflect the meticulous naturalism of Henri de Braekeleer. The artists Corinth met through Gorge were most likely associated with Als Ik Kan. He may also have been aware of the more adventurous efforts of Les Vingt, who held their first exhibition in Brussels in 1884, but in any event he was not impressed by what he saw of contemporary Belgian painting.

By 1884, Corinth later said, "the time of Rubens and Brouwer and the history painters Gallait, Verlat, and Leys was over."[36] He was not entirely correct. Charles Verlat still taught at the Antwerp Academy in 1884 and was not appointed director of that institution until 1887. His advocacy of a native tradition in painting in fact set the tone for the organization Als Ik Kan until the early years of the twentieth century.[37] Though colored by negative feelings, Corinth's comment reflects his own early admiration for nineteenth-century history painting. It also suggests that he engaged in more than a fleeting dialogue with the leading masters of the Flemish baroque. Although he knew paintings by Rubens and Jordaens from the collection in the Alte Pinakothek, only on Flemish soil did these masters begin to inspire him. The four paintings he completed in Antwerp all show a marked increase in colorism and a freer handling of the paint.

In the portrait of Paul Eugène Gorge (Fig. 13) Corinth juxtaposed the grayish blue of the background with the sitter's ruddy complexion and blond hair. The paint has been applied in fluid strokes, accentuating the contrasts of light and shade engendered by a strong source of illumination just outside the picture to the sitter's left. Gorge's posture is casual and relaxed. His gentle gaze gives credence to the purity of character Corinth admired in him, which helped to forge a lasting friendship between the two men.

Still more vigorous, in both execution and expression, is Corinth's painting of a black man (see Plate 2), poetically inscribed "Un Othello" in the upper right. The shirt, painted with a broad, loaded brush in stripes of red and white, stands out boldly against the grayish black ground. The subtle turn of the torso and the figure's close proximity to the picture frame reinforce the impression of immediacy conveyed by the energetic brushstrokes. Despite the literary allusion of the title, the portrait is no more than a character study, possibly of a sailor from the Antwerp harbor; it compares favorably with Rubens's similarly sympathetic studies of foreign sailors. Although it has been widely as-

Figure 13

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Painter Paul Eugène Gorge , 1884.

Oil on wood, 56 × 46 cm, B.-C. 22. Von der Heydt-Museum

der Stadt Wuppertal, Wuppertal-Elberfeld.

Photo: Studio van Santvoort.

sumed that Corinth was directly inspired by Rubens's and Jordaens's paintings of blacks,[38] it is unlikely that he knew these works at this time since they were not on public view. The sensitive conception that the painting shares in particular with Rubens's oil sketches must simply be accepted as a case of parallelism. Wilhelm Trübner's pictures of black men, painted in 1872 and 1873, might have served as iconographic precedents. Although Corinth did not mention seeing these until many years later,[39] they could have been among the works he had pondered at the weekly exhibitions of the Munich Artists' Association in the early 1880s. But even then Corinth's portrait remains highly original, differing markedly in its forthright naturalism from Trübner's predominantly anecdotal approach.

Although Corinth spent his last month in Antwerp in the congenial company of his father, his dislike for the city continued to grow. To make matters worse, when he submitted to an exhibition in Brussels a painting for which he had entertained great hopes, it was rejected by the jury. In 1917 he still remembered his disappointment acutely. "Out of revenge," as he put it, he eventually overpainted the picture with a kitchen still life (B.-C. 68) because it continued to remind him of the rejection.[40] Fortunately, news reached him at about this time that The Conspiracy , which he had sent to London, had been awarded a bronze medal. When he later referred to the painting as his "fledgling work,"[41] he was no doubt thinking of this, his first public recognition. The unexpected success apparently gave Corinth the confidence he needed to conquer his fear of the hostile French, for he quickly determined to leave Antwerp and to continue his studies in Paris after all.

At the Académie Julian

Corinth arrived in Paris in early October 1884 and enrolled in the Académie Julian. Founded in 1868 by Rodolphe Julian, a minor painter who exhibited at the Salon des Refusés in 1863 and several times between 1865 and 1878 at the Salon proper, the Académie Julian was not an academy in the traditional sense but a place where students could draw and paint from the live model and profit, if they so desired, from an informal weekly critique. Although Julian had originally opened the school to prepare students for the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts, by the early 1880s the two schools had become rivals. The Académie Julian was especially popular among students from abroad, even though they paid tuition there whereas study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts was tuition free. Because the école was unable to admit all ap-

plicants—and because French taxpayers resented financing the training of foreigners—the Ministry of Fine Arts required foreign applicants to take a French language test so rigorous that only a few managed to pass it. Julian, by privately engaging teachers from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, including such famous pompiers as Adolphe Bouguereau, Tony Robert-Fleury, Gustave Boulanger, and Jules Lefebvre, helped foreign artists to circumvent the language test: on payment of hard cash, they could study under the école's leading masters without having to be admitted to the school itself. Moreover, because the "visiting professors" were usually also on the Salon juries, Julian's students stood to benefit substantially when they submitted their entries for acceptance to the annual Salon exhibitions.

Besides foreigners, the student body included young painters who rejected the école on principle and availed themselves of Julian's facilities because they could draw and paint there without much interference. Even at Julian's some of these students defiantly turned their paintings to the wall when the teachers came to offer their critiques. Many older artists kept returning to the Académie Julian because there they could count on having professional models to work from. According to one observer, only at Julian's did one find that "unique flesh, hearty and fair, with that particular touch of a supple glimmer."[42]

Julian's enterprise turned out to be highly successful. He eventually opened branch academies throughout Paris, including several studios for women. Over the years the foreigners at Julian's included the Russian Marie Bashkirtsev; the Englishman George Moore; the Swiss Félix Vallotton, Cuno Amiet, and Giovanni Giacometti; the Spaniard Ignacio Zuloaga; and the Finnish painter Aksel Gallén-Kallela. Among the Germans were Ludwig von Hofmann, Max Slevogt, Ernst Barlach, Georg Kolbe, Emil Nolde, Käthe Kollwitz, and Paula Modersohn-Becker. The better-known Frenchmen who attended the Académie Julian include Paul Sérusier, Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Fernand Léger.

Each of Julian's branch academies consisted of a group of hot, airless rooms crowded with noisy students whom a massier —a senior student responsible for sundry tasks in the atelier—was expected to restrain from the most flagrant disorder. The walls of some studios were covered with palette scrapings and caricatures; others, more decorous, were adorned with framed student drawings; still others displayed signs with such famous pronouncements by Ingres as "Le dessin est la probité de l'art," "Cherchez la caractère dans la nature," and "Le nombril est l'oeil du torse."[43]

Corinth attended the "little studios" at 48, Faubourg Saint-Denis, where his teachers were Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) and Tony Robert-Fleury (1837–1911). On his arrival he was greeted with deafening noise, followed by caustic remarks intended to unnerve a newcomer. Troubled by the attention, Corinth though it wise to keep his East Prussian origins a secret and responded to his fellow students' insistent questioning about his background and training by implying that, having studied in Munich, he was a "Bavarois." He was formally initiated into the group at an "altar" of atelier stools quickly set up for the occasion, a ceremony recorded in an old photograph.[44] A few days later he was sketched in caricature on the studio wall in the uniform of a Bavarian soldier against a red background and with bloody hands. The pithy inscription under it, "Quand même" (in spite of everything), indicated that for his French fellow students he was still a German.[45] As it turned out, however, Corinth got along well with everyone, partly, it seems, because his massive build and unmistakable physical strength commanded respect. Yet le gros Allemand , as he was called, never formed a real friendship with any of the French students. Nor did he ever mention Gallén-Kallela, who studied at Julian's at the same time. His closest acquaintances included another East Prussian, Franz Lilienthal; the Bavarian Ludwig von Zumbusch; and four young Swiss painters—Emil Beurmann, Louis Calame, Emil Dill, and a fellow from Zurich named Blaas. In his memoirs Corinth disguised the identity of his friends: Zumbusch is von Sambitsch, Lilienthal is Blumenthal, and Beurmann is probably the Swiss Mauerbrecher. Dill, Calame, and Blaas are not mentioned, although the latter two are commemorated in portrait drawings.[46]

Corinth made up his mind to remain in Paris for at least three years "to learn whatever there was to be learned";[47] even after eight years of study in Königsberg and Munich he apparently believed he could progress further only at still another academy. Moreover, he resolved to return to Germany only when he had distinguished himself at the Salon.

Although he was in Paris, Corinth remained unfamiliar with the works of the French Impressionists. He arrived too late for the memorial exhibition of Manet at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, although he was in time for the next show, the large retrospective held in 1885 for Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose pseudo-impressionist brushwork and diluted colors may have embodied for Corinth the latest word in French modernism. On his frequent visits to the fashionable galleries of Georges Petit, a veritable sanctuary of academic art, Corinth admired the fabulous naturalism of Meissonier,[48] but since he spent the summer of 1885 vacationing in the Black Forest and that of 1886 on the Baltic seacoast near Kiel, he missed Monet's and Renoir's paintings at Petit's

fourth and fifth expositions internationales . Most likely Corinth encountered Impressionism only in the extreme form of Neo-Impressionism when in December 1884, seemingly by chance, he walked into the Salon des Indépendants,[49] where he saw works by Seurat, Signac, Guillaumin, Cross, and others, including a landscape sketch of the island of La Grande Jatte, a first study for Seurat's large painting.

Corinth's unfamiliarity with Impressionism is not really astounding, for French hostility toward German artists in Paris seems to have fostered a provincialism that did much to exclude them from the inner circles of the then developing avant-garde. Max Liebermann's earlier experience in Paris and Barbizon from 1873 to 1878 was similar,[50] although he must have known of the Impressionists, especially since Lepic participated in the first historic exhibition at Nadar's in 1874 as well as in the second Impressionist show in 1876.

Corinth, at any rate, craved the recognition only the Salon could confer. Having determined to remain in Paris until he had exhibited something at the Salon and possibly won at least a mention honorable ,[51] Corinth found his inspiration in the Louvre and in the Musée du Luxembourg, then the repository of important works that the French state had acquired from the country's leading academicians. The Académie Julian, too, seemed to offer a road to success. Corinth took particular pride in having peers like René Ménard and Etienne Dinet in the studio; both men were already hors concours , having sufficiently distinguished themselves so as not to require prior approval to exhibit their works at the Salon. And he was especially delighted to discover that the young history painter Georges Rochegrosse, whose painting of the slaying of Aulus Vitellius he had admired in Munich in 1883, was working in the neighboring studio of Boulanger and Lefebvre.[52]

Robert-Fleury's impact on Corinth's development is difficult to measure. In the course of his weekly critiques Bouguereau, however, soon developed a liking for le gros Allemand and after the success of The Conspiracy in London, saw that the painting was accepted at the Salon of 1885. Corinth rejoiced at this auspicious development. He wrote in Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben :

In all of Paris there was no one happier than the East Prussian Heinrich Stiemer [Corinth's pseudonym]. He was strutting around like a dandy and intended to get himself a genuine Parisian suit. He stopped in front of every shop to see what else he might buy; . . . each window reflected his massive figure in an entirely new light. "This then is the way a man looks on his first step to fame," he kept telling himself. He was sure now that he would catch up with that fellow Rochegrosse. That no longer worried him.[53]

Figure 14

Adolphe William Bouguereau, A Nude Study for

Venus , c. 1865. Pencil heightened with white,

46.2 × 30.3 cm. Sterling and Francine Clark Art

Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts (1578).

In his autobiography he wrote that acceptance at the Salon seemed "a promise for my art in the future . . . that everything would turn out in the best possible manner."[54] Unfortunately, his painting was displayed near the ceiling. It hung so high that it seemed to him no bigger than a postage stamp— and apparently had as little effect on the public and the critics.

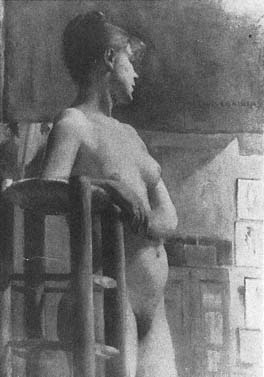

Of the twenty pictures Corinth is known to have painted in Paris, no fewer than fifteen are devoted to the nude human figure—a considerable increase over the two nudes he had painted during his preceding eight years of study, the Crucified Thief (see Fig. 10) and a half-length female nude (B.-C. 11), apparently also done in Löfftz's studio in 1883. The comparatively large number of nudes from Paris is not surprising, considering the emphasis at the Académie Julian on working from the live model. According to Hermann Schlittgen, who studied briefly with Lefebvre in 1886, "If the better works reminded one of anybody, it was Ingres. . . . to represent the nude figure as correctly as possible . . . was the goal of everyone."[55]

Figure 15

Lovis Corinth, Female Nude at Atelier Stool ,

1886. Oil on canvas, 73 × 50 cm, B.-C. 29.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

The nude was not only the focus of the curriculum at Julian's but also an important element in the oeuvre of Bouguereau, whose reputation rested on such a vast gallery of bathers and nymphs that some critics facetiously claimed he kept a studio of nudes the way others ran brothels.[56] Bouguereau continued the tradition of David and Ingres, except that he popularized the severe style of his predecessors by endowing his nudes with greater erotic appeal, an effect he achieved by allowing his models to retain a distinctly "real" look. The preparatory study for Venus (Fig. 14), one of the figures in the monumental ceiling decoration in the concert hall of the Grand-Théâtre in Bordeaux, is typical of Bouguereau's skillful combination of realism and idealization. The head is that of a contemporary woman; the body, however, is exactly eight heads tall, four each above and below the pelvic region.

Corinth's female nude of 1886 (Fig. 15) is one of several of his pictures that exemplify the careful observation of the human figure Schlittgen described. But in his drawings he generally moderated this factual approach by emulating

Figure 16

Lovis Corinth, Three Studies for

a Reclining Female Nude ,

c. 1884–1886. Charcoal and pencil,

44.7 × 29.5 cm. Kunsthalle zu Kiel.

Photo: Horst Uhr.

Bouguereau's more agreeable style. Indeed, Bouguereau specifically encouraged Corinth to attend to his draftsmanship when he offered the criticism "Ce n'est pas mal, mais ce n'est pas bien dessiné" —an admonition Corinth never forgot.[57] Three drawings on folio 23 verso in the sketchbook in Kiel (Fig. 16) illustrate Corinth's efforts to idealize the figure of a reclining female nude. The rapid sketch at the bottom of the page is followed by a rendering in the center in which the figure's contours are indicated more specifically without suppressing the model's ample forms. In the uppermost drawing the body of the nude is charted once again in successive contours, but this time a reinforced outline reduces the awkward curvature of hip and shoulder to a smoothly flowing rhythm that gives continuity and greater refinement to the model's fleshy forms. In some drawings Corinth tried to work out a system of proportions like the one Bouguereau had used for the figure of Venus. In others, such as the study of a reclining female nude on folio 24 recto of the Kiel sketchbook (Fig. 17), he employed hatching and crosshatching and the alternative method of the estompe to give the figure added relief. The generally untidy execution, Corinth's inability to render the interplay of the limbs convincingly, and his consistent avoidance of such complex anatomical details as hands and feet confirm that Bouguereau's criticism was well founded.

This drawing, incidentally, calls attention to a practice popular among the French pompiers . By rapidly outlining a crouching male nude in the back-

Figure 17

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude (Study for Jupiter and Antiope ),

c. 1885. Pencil, 29.5 × 44.7 cm. Kunsthalle zu Kiel.

Photo: Horst Uhr.

ground, Corinth transformed the original study of the live model, almost playfully, into a mythological composition. The mundane Parisian model has become Antiope about to be surprised in her sleep by Jupiter, who approaches in the guise of a satyr. Paintings of the nude had this particular advantage of being easily "finished" for the Salon by the addition of a few anecdotal details. Cabanel's famous Birth of Venus (1863; Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and many a naiad by Jean-Jacques Henner are no more than paintings of nude models in which minimal accessories supply the requisite iconographic context. They are descendants of Ingres's La Source (1856; Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and belong to a seemingly endless line of nudes shown at the annual Salons with predictable success. Both Löfftz's Christ Lamented by the Magdalene (see Fig. 9) and, as already noted, Corinth's own Crucified Thief (see Fig. 10) bear witness to the widespread popularity of this approach, although probably nowhere outside Paris was the custom pursued with the same verve. Bouguereau's painting of the Oreads (1902; private collection, Paris), which contains more than thirty-five such nudes, may be the most extreme example of this practice. Corinth, possibly inspired by Ingres's 1851 painting of the subject (Musée d'Orsay, Paris) as well as by Titian's problematic composition in the Louvre, the so-called Pardo Venus (c. 1535–1540/c. 1560), devoted at least six more pencil studies as well as an oil sketch (B.-C. 28) to the subject of Jupiter and Antiope. This composition may be related to the painting of a life-size

Figure 18

Lovis Corinth, Recumbent Male Nude , c. 1886. Pencil,

29.5 × 44.7 cm. Kunsthalle zu Kiel.

Photo: Horst Uhr.

"nymph" Emil Beurmann saw in Corinth's Paris studio, which he said Corinth was working on with the intention of sending it to the Salon.[58] This painting, if indeed it was ever completed, has long since disappeared. Corinth's hopes for it are suggested by his lighthearted gesture years later of repeating the composition where he concludes his account of the Académie Julian in Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben . There the recumbent nymph lies asleep as a satyr, now conspicuously goat legged and horned, approaches with manifest glee. To the ornate frame of the vignette is affixed a proud "Hors concours."[59]

Another motif Corinth was working on at this time was "a corpse of Christ on a red tile floor."[60] His brief but unequivocal description indicates his casual approach to the subject, and a preparatory drawing in the Kiel sketchbook (Fig. 18) confirms that this picture, too, was to have been an accurate, though somewhat idealized, study of a male nude whose posture would suggest the appropriate iconographic context. This drawing and the studies for Jupiter and Antiope suggest that Corinth's thematic interest was limited to a preoccupation with form as manifested in the model. Many years were to pass before he saw the human figure as a vessel of emotions whose expressive power transcended the impeccable rendition of nature as Ingres and Bouguereau understood it.

Whenever the students at the Académie Julian were not drawing or painting the nude, they were working on figure compositions that had to be completed without the aid of models. This practice allowed them to experiment with the arrangement of figures within a chosen format, to determine the distribution of light and shade, and to examine the effects of the colors they intended to use. Bouguereau, who saw to it that this practice was followed faithfully, usually posted a note near the studio door announcing the individual assignments. This might be a well-known but complex theme, such as "The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem," or something more erudite, like "The Scythian King Scylurus Admonishes His Eighty Sons."[61] Corinth's composition study of 1885, entitled Unity Gives Strength (present whereabouts unknown), derives from Plutarch's story, except that he reduced Scylurus's large family to five, a handier number.[62]

Several studies for a Lamentation, probably executed at about the same time, illustrate Corinth's efforts to achieve both variety and unity in a composition involving a similarly heterogeneous, though far less unwieldy, group of figures. They too demonstrate his continued reliance on the leading pompiers and can be traced to such prototypes as Henner's paintings The Dead Christ (1879; Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and Christ in the Tomb (1884; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille) and Bouguereau's Virgin of Consolation (1877; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg).[63]

No other works from Paris shed further light on Corinth's early development. Those he completed in the summer of 1885 and 1886 while traveling in the Black Forest and in Holstein—landscape studies, oil sketches and more finished pictures of country folk, and two plein air portraits—are of only marginal interest. Most were conceived without regard to the tastes prevailing at the Académie Julian. In two exceptions from the summer of 1886, however— compositions known only from later descriptions—Corinth adapted his recent experience of working from the live model to plein air painting. He asked several old men from a home for the aged near the village of Panker in Holstein to pose nude for him in the woods, in the guise of Pan and other forest spirits. Corinth, oblivious to the men's physical discomfort in the brisk forest air, not to mention their reluctance to comply with his unusual request, apparently took delight in the effects of the sunlight flickering across naked bodies. Perhaps the forest interior of 1886 (B.-C. 43), in which a seated nude figure can be seen from the back, originated in this context. No other visual evidence has survived either of these plein air figure compositions or of a large picture Corinth painted inside the old people's home.[64] The men were smoking and reading; the women kept busy spinning or knitting. A soft glow, reflected from a wheat field just outside the window, pervaded the room.[65] Although Corinth

destroyed these paintings because he found fault with them, in the picture of the old people's home he had returned to the pictorial problem of interacting light and interior space that had first occupied him in The Conspiracy .

A renewed interest in this problem also prompted the lively figure composition Cardsharp (Fig. 19), one of the last pictures Corinth painted in Paris during the spring of 1887. Three cardplayers in a Paris bistro challenge and threaten a cheat; a waiter and an older man look on. Corinth, who had not exhibited at the Salon since the spring of 1885, may have hoped to repeat his London success with a work that offered a similar challenge, except that now he heightened the narrative suspense by emphasizing the transitory moment of the action, as Meissonier had done in a similarly charged picture entitled The Brawl (1855; Collection H. M. Queen Elizabeth II). Corinth's care in preparing the painting is evident from preliminary drawings.[66] It is not known, however, whether he submitted the work for acceptance to the Salon in 1887. In any case, the jury rejected all his entries, dealing him a devastating blow. This "misfortune," as he later called it,[67] led him to pack his belongings and return to Königsberg. He eventually destroyed the Cardsharp , apparently for the same reason that led him to overpaint the picture rejected in Antwerp.

Despite the disappointing finale to his studies in Paris, Corinth never ceased to respect the discipline he had learned at the Académie Julian, no matter how far his work digressed from the precepts of artists like Bouguereau. In his own teaching manual, published more than twenty years later, he repeatedly emphasized the importance of studying the live model and recommended that the nude be rendered accurately, as if it were but another three-dimensional object like those encountered elsewhere in nature in landscapes, animals, and still life.[68] This advice, true to nineteenth-century academic notions,[69] also confirms the nonpsychological approach to the human figure seen in Corinth's early drawings and paintings of the nude. Besides the concept of form exemplified in the live model, Corinth passed on to his students the principles of composition he had first learned at Julian's. To illustrate the "mental gymnastics" he felt every aspiring artist must learn to do, he published one of his Paris studies for the Lamentation in his teaching manual.[70] An artist approaching the story in Genesis 37:32, where the sons of Jacob bring their father the bloodstained coat of their brother Joseph, he explained, must begin the composition by visualizing gestures and expressions appropriate to the remorse and pity each of the brothers feels in anticipation of the old man's grief.[71] Even Corinth's good friend Walter Leistikow, in an amicable review of Corinth's teaching manual when it was first published in 1908, could not forgo an aside

Figure 19

Lovis Corinth, Cardsharp , 1887.

Oil; ground and size unknown, B.-C. 50.

Painting destroyed by the artist.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

about Corinth's eccentric approach: "Today, under the banner of Impressionism and a thousand other groping efforts to come up with something new and newer still, . . . Corinth writes a painting manual just as in the good old days when the blessed Saint Academicus was still absolute ruler in the realm of art."[72] When a year earlier Corinth's student Oskar Moll had told him of his plans to go to Paris to study with Henri Matisse, Corinth had gruffly replied: "What do you want to go to Paris for? The old Bouguereau is dead, and there is nothing new."[73]