PART II—

SEVEN TOWNS

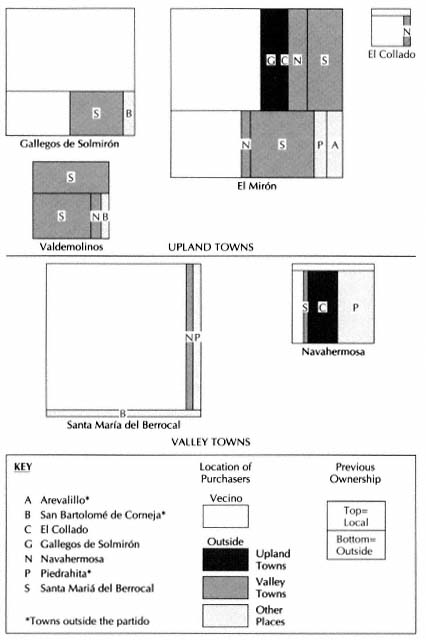

The first part of this book has studied the course of royal policy toward agriculture in the second half of the eighteenth century. It observed the failure of Carlos III's attempts to increase the number of small farmers and the modifications in the philosophy of agricultural reform and the demands of the royal fisc that culminated in the disentail of ecclesiastical properties under Carlos IV. The second part aims to be a parallel study of the evolution of rural society and agriculture at the local level. Its subject is seven communities in the provinces of Salamanca and Jaén, two provinces in distinct parts of Castile that experienced high levels of disentail. In each community it will analyze the farming patterns, the social structure, the level of income of the communities as a whole and of the occupational sectors within them, the economic relations with the outside world and their effect on local conditions, and the power structures. When possible, it will indicate the direction of evolution, especially of the population, the agricultural patterns, and income. For each community it will then observe the process of desamortización and relate it to prior conditions and current developments. This part thus proposes to describe, in these individual cases, the local reality that royal policy sought to improve and the effect on the local reality of the execution of the royal decrees. One may then form some judgment of the accuracy of the perceptions of the king's counselors and of the wisdom of their policies. The developments in seven towns can also suggest conclusions on the wider evolution of Spanish agriculture and rural society at the end of the old regime. These conclusions can be put to more general

tests in Part 3, which deals with the provinces of Salamanca and Jaén as a whole.

Within these provinces, I selected for detailed study rural communities in which the Madrid records show that there were numerous sales and for which the provincial archives have full or nearly full records. The two major sources at this level are the catastro, or survey of individual and institutional property and personal income, executed in the provinces of Castile in the 1750s under the direction of the Marqués de la Ensenada and the archives of the contadurías de hipotecas founded by Carlos III in 1768.

Undertaken to make possible the substitution of a single tax on income to replace the complex tax structure of Castile inherited from the Middle Ages and the Habsburg era, the catastro is one of the most extensive sources in existence for social history in the early modern period. Its basic feature is a series of town-by-town surveys conducted under the guidance of royal agents. Where preserved these town surveys are bound in volumes, with several volumes for each place unless it was tiny.[1] The first part, known as the respuestas generales or autos generales, consists of answers to forty questions covering the geographic limits of the town; the number and kinds of buildings; the crops raised and their average price; the different qualities of land in the town and their average yield; the income from livestock, forests, and other natural resources; the amount of tithes, seigneurial dues, royal taxes, and other impositions on the town; and the number of people engaged in each kind of occupation, with their daily wage or annual income. This part is followed by the libro personal de legos and the libro personal de eclesiásticos. These are lists of all the individuals in each household, the first of laymen and the second of households headed by an ecclesiastic. They provide the name and occupation of the heads of household (male or female) and a list of all others in the household with their relationship to the head of household. Frequently all personal names are given and the ages of all males. Much miscellaneous information is also preserved in these volumes, but it varies from town to town. They are invaluable sources for studying family size and structure and its relation to social class and occupation. The third main part of each town's catastro, the most extensive, is formed by the libro maestro seglar and the libro maestro eclesiástico. These give household-by-household and institu-

[1] See Matilla, Única contribución, 77 n. 64, for a list of those provinces where the volumes are in existence. It records Jaén as missing, but this is incorrect; most of the volumes are available.

tion-by-institution surveys of all the property, real and animal, in the town. They give the name and occupation of the owner, followed by his livestock (pigs, sheep, goats, and larger animals, not dogs, chickens, and small animals), his houses, and his fields. Individual income from official positions, professions, and commerce is also listed, but not from daily wages and sale of the products of handicrafts (the latter information appears in the respuestas generales). Real properties are identified by their location within the town limits (property that the vecinos owned in other towns would be listed in their catastros) with the names of owners of adjoining properties, number of rooms and size of buildings, extent and quality of fields, number of trees in orchards, and so forth. Municipal and ecclesiastical properties are surveyed in equal detail (the latter in separate volumes), and the volumes can be hundreds of folios long.

The planners of the catastro took pains to keep the records of lay property (including municipal property) separate from those of ecclesiastical property. The latter records served the crown well when Carlos IV began the disentail of the endowments of obras pías. They are also useful to the historian, for they make possible the identification of the properties sold and their place in the economy of the town. Furthermore, they can be presumed to be fairly accurate, because the volumes were read aloud at town meetings that often lasted more than a full day and were then certified as correct by the leading vecinos. It would have been difficult for any privileged person to falsify his record unless he had the town completely under his thumb. In only a few cases have I found properties sold that do not appear in the catastro.

The other main source at the provincial level is the records of the contadurías de hipotecas. By a pragmatic sanction of 1768, Carlos III ordered each cabeza de partido to establish an oficio de hipotecas under the charge of the notary of the municipal council. It was to keep a record of transfers of real property and liens on property. These offices later became known as contadurías de hipotecas. In the nineteenth century their name changed to registros de propiedad, as they are known today. From my experience, as late as 1969 the registry of sales or transfers of property with these offices was voluntary, and the archives indicate that the contadurías were not very active until the beginning of disentail, when they were ordered to record the sales. Most of their records from 1799 to 1808 concern the disentail. The registros de propiedad took over their records, and recently care of them has been assigned to the provincial historical archives.

Not all their records have been preserved in either Jaén or Salamanca

province, but those that do exist give vital information for the study of the process of disentail under Carlos IV at the local level. They furnish synopses of the notaries' records of sales, providing the name and domicile of the former owner and the buyer and a description of the property that usually makes possible its identification in the catastro. Information that is vague or incomplete in the Madrid records is here specific. Furthermore, the records are kept by town; thus they make relatively rapid a process that would be almost interminable if one had to search for the original deeds of sale of a certain town in the records of all the notaries who might have executed them, even if none of them had been lost. Unfortunately, some buyers were lax about registering their titles, so that there is no assurance that the contadurías provide a complete record of sales of any one town. Sales turn up in the Madrid archive that they do not list; nevertheless, without them it would be very difficult to recreate the process of disentail at the town level.

Finally, when they are available, one of the most valuable sources for information on local economic activity is the parish tithe rolls. In the second half of the eighteenth century, the prelates of Salamanca began to require the parish tithe collectors (cilleros ) to keep accounts of the payments made by each farmer, instead of noting only the total of the various crops collected in the parish each year, as had been the prevailing practice. This reform lets us see not only how many people were farming in a town but how much each one harvested. We can draw an economic pyramid of the farmers and locate in it those persons who bought property in the disentail. Unfortunately few parish tithe rolls (tazmías ) seem to have been preserved, and those that have been are hard to locate since they are uncatalogued in the shelves of the village churches or the homes of the incumbent priests. Two were already known in Salamanca province, those of La Mata and Villaverde, both close to the capital, and an extensive search on my part through the south of the province unearthed a third, in El Mirón (today in Ávila province). I chose these three towns to study because of the completeness of the information on them. I selected a fourth, the rural estate of Pedrollén, as an example of a different kind of region and community.

In Jaén province, as probably in most of Andalusia, where parishes were large, the ecclesiastical authorities farmed out the collection of tithes to private individuals. These tithe farmers (administradores ) contracted to pay fixed amounts of money or crops to the religious institutions entitled to receive the tithes and collected the payments due from the farmers, keeping as their profit the difference between what they col-

lected and what they paid. In bad years their profit could turn to loss, and they had to demonstrate in bidding for the contract that they had the financial resources to be able to absorb losses. What accounts may have been kept of payments by individual farmers were in the hands of the administradores and have most likely been lost or destroyed. I found no trace of any and therefore I selected three towns in different parts of the province for which we have catastro and contaduría records, where a considerable amount of land was disentailed and which were not too large to be manageable. They are Baños, Lopera, and Navas de San Esteban del Puerto.

These seven rural communities run the gamut from a large estate through small villages to a town of nearly two thousand people. For simplicity I refer to them all as towns, begging the indulgence of sticklers for definitional accuracy. Let us turn first to the towns of Salamanca, which are smaller than those of Jaén and for which I have fuller information.

Chapter VII—

La Mata

The city of Salamanca is built on a group of low hills on the northern bank of the Rio Tormes some distance upstream from its confluence with the Rio Duero. The Duero is the major river of the northern meseta, and the Tormes is its main tributary from the south, bringing waters from the northern slope of the massive Sierra de Gredos. An impressive Roman bridge of twenty-six stone arches crosses the Tormes at Salamanca, a witness both to the volume of the river at its height and the secular importance of the city as the center of a rich agricultural region.

The urban skyline stands out above the valley, marked by the two cathedrals, the new one of the sixteenth century with the older Romanesque one tucked in its shadow, and the numerous convents and parish churches, so many that Salamanca has been known familiarly as Little Rome. Lying lower and less visible are the buildings of the university and associated colleges, mainly of the Renaissance. Under Felipe V, a more worldly age, the heart of the city was torn out to create the Plaza Mayor, a large open square surrounded by a four-storied building with arcades and shops on the street level and apartments above. The city hall dominates its northern side. The Plaza Mayor is a beautiful example of early modern city planning and a reflection of the wealth pouring into the metropolis in the eighteenth century, for it rivals the older Plaza Mayor of Madrid in size and surpasses it in elegance.

Behind the eighteenth-century limits of the city is a rise; over the top of it stretches to the north a broad, gently rolling plain marked by the beds of a few streams and an occasional low hill. The plain of La Ar-

muña is one of the richest grain regions in dry Spain, characterized by thick, red soil that can be plowed deeply and holds its moisture when regions of thinner cover have dried up. In the eighteenth century many nucleated villages dotted the plain, as they still do today. They lie only three or four kilometers from each other, so that the view from any of the low rises includes a number of distinct settlements, each surrounded by wheat fields, green and lush in the spring, brown and dry after the summer harvest. Communication by cart was easy from town to town and into the city.[1]

Near the center of the plain, at an altitude of 818 meters, lies the village of La Mata, about twelve kilometers due north of Salamanca. Like most of the villages of the region, in the eighteenth century it was classed as a lugar, the lowest administrative entity with its own government. Approaching La Mata one saw first a stocky granite church sitting on a slight knoll in the middle of undulating fields. The church was squat and simple, lacking the square stone tower that decorated those in neighboring villages and suggesting that this community might be less wealthy than its neighbors. Around the church and running down the gentle gradient to the southwest were the public buildings and the low stone houses of the townsmen. The casa consistorial, or town hall, faced a small square below the church and held also the town jail. In addition the town council possessed a butcher shop and a smithy, which it rented out, and a storehouse that was used as the town granary (pósito). La Mata had sixty inhabited houses and two others that were empty, thirteen barns (pajares ), eight corrals, and two more granaries (paneras ), which belonged to the church and stored the product of the tithes. In one of the houses a vecino ran a tavern, where he sold wine and a few groceries.[2]

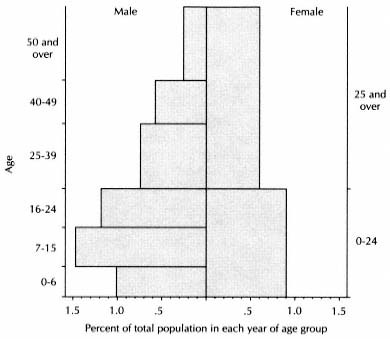

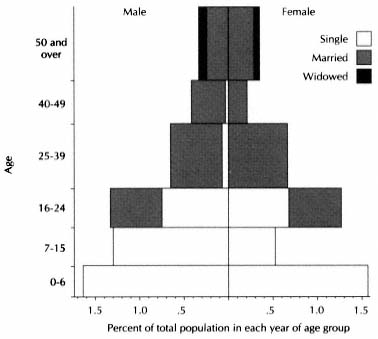

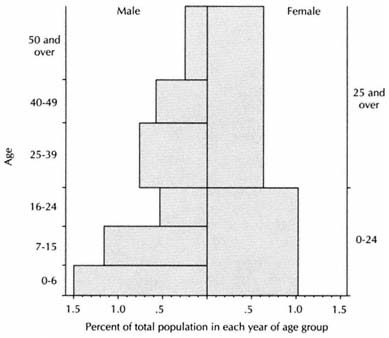

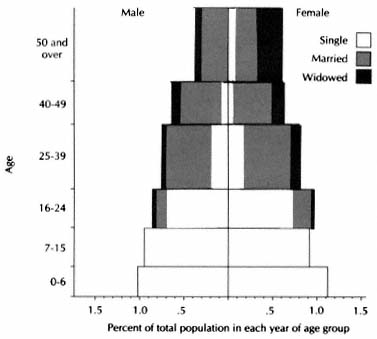

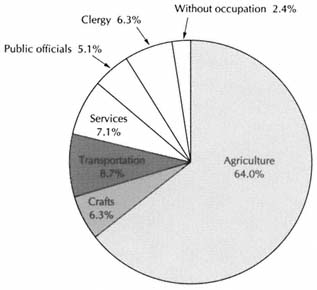

La Mata had a population of somewhat more than two hundred. According to the catastro, fifty-nine of these, including ten widows, were vecinos or heads of household. Twenty-two vecinos, including two widows, one-third of the total, made their living from farming. Twenty-three were arrieros, muleteers who transported goods for hire. A linen weaver, a shoemaker, the tavernkeeper, a schoolmaster, a surgeon-bloodletter, and the parish priest were the remaining male vecinos,

[1] For a fuller description of the geography of La Armuña, see Chapter 17 and Appendix Q.

[2] AHPS, Catastro, La Mata, libro 1421, resp. gen. QQ 22, 23, 29; libro 1419, maest. ecles., ff. 8, 48.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

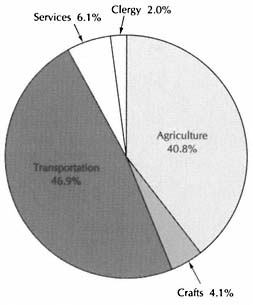

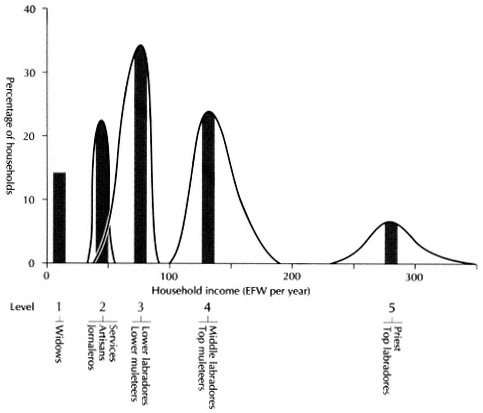

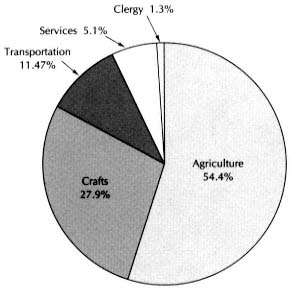

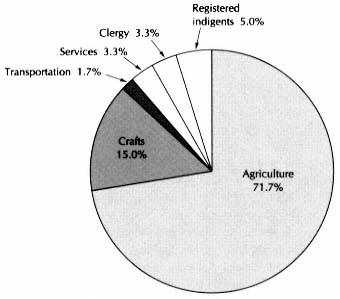

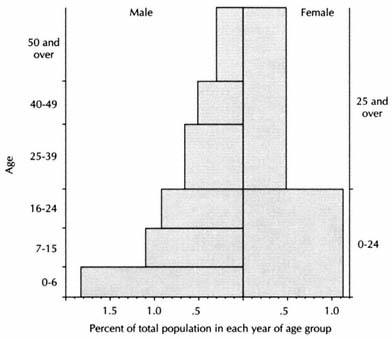

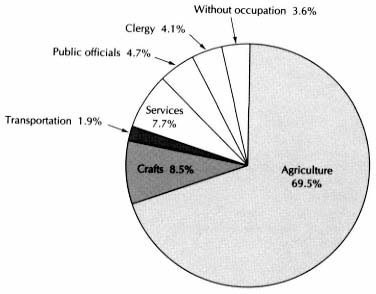

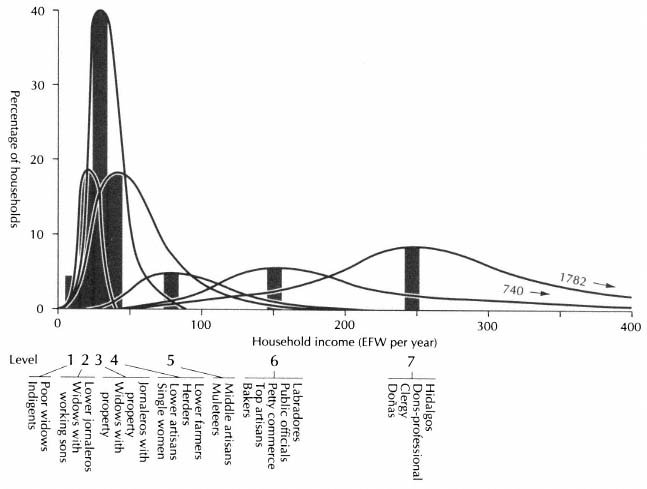

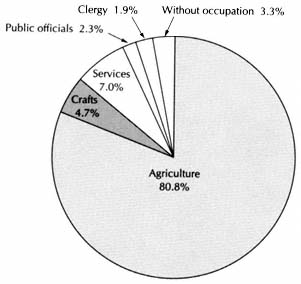

while the other eight widows had no specified means of support (Table 7.1 and Figure 7.1).

The término, or area of the town, was small; only half a league from east to west and three-eighths from north to south was what the vecinos reported to the makers of the catastro.[3] From the top of the knoll they could see similar towns in all directions. To the east La Mata bordered

[3] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 3. A legua was traditionally the distance covered in an hour's walk, about five kilometers.

Figure 7.1.

La Mata, Employment Structure, 1753

on Carbajosa de Armuña and to the west on Castellanos de Villiguera. Slightly further to the south was Monterrubio, at the foot of the small reddish hill that gave it its name, and to the northeast the twin towns of Palencia de Negrilla and Negrilla de Palencia, hardly a stone's throw apart. In addition, La Mata bordered on three despoblados or alquerías (the terms meaning literally "depopulated place" and "grange" were used almost interchangeably and indicated that a caretaker, a herder, and a few others might live there, but probably not the owner): Narros de Valdunciel on the northwest and Aldealama and Mozodiel del Camino on the south.[4] These occupied poorer land, some of it good only for grazing. So flat is the terrain, despite its gentle roll, that, even today, on clear days the vecinos of La Mata see La Peña de Francia, a sharp mountain on the southern border of the province, seventy-five kilometers away (see Map 7.1).

The catastro, dated 1753, and the register of tithe payments at the end of the century permit the reconstruction of the economic and social

[4] Ibid. Q 2.

Map 7.1.

La Mata and Its Environs

structure of this small rural community.[5] It is convenient to determine first insofar as possible the income of the different households and the total income of the village. With this economic profile before us, we can then observe how this society was evolving in the second half of the eighteenth century and what impact the disentail of Carlos IV had on the course of its development.

The makers of the catastro recorded the area of La Mata outside the town nucleus as 1,073 fanegas (480 hectares).[6] This is about 18 fanegas

[5] For the tithe records, see Archivo Parroquial, La Mata. I was able to copy this record thanks to the hospitality of the late parish priest, don Jerónimo Pablos, who made me welcome in his house for some ten afternoons in 1964 and 1969. This venerable gentleman also told me much about the town itself and the Armuña district. The pleasure of such interchanges is one of the unsung perquisites of the historian's craft.

[6] This is the total given at the beginning of maest. segl. La Mata, resp. gen. Q 10, says 1,100 fanegas but is less accurate. The local fanega was 400 estadales of 16 square varas each, or .447 hectares 1.13 acres) (ibid. Q 9). See Cabo Alonso, "La Armuña," 113.

for each of its vecinos, far below the Armuña regional average of 48 fanegas per vecino.[7] The fertility of La Mata's land, however, compensated partially for what it lacked in extent. The catastro's estimate of the productivity of the land in La Mata averages out at an annual return of forty reales per fanega. This is well above the regional average of twenty-seven; only five towns in La Armuña had more valuable land, and La Armuña was the richest district in the province. The value of La Mata's soil lay in its ability to produce first-class wheat, trigo candeal. Ninety-one percent of the término was wheat land (sembradura de secano que produce trigo ), 3 percent was devoted to rye (centeno ), and the rest was meadow (prados de secano para pasto ). None of the land in the town was barren or waste. Furthermore, both wheat and rye fields were sown every other year, whereas in most parts of arid Spain the land could produce a crop only once every three years or less often. The meadows were mowed for hay every year. Few towns in arid Spain could match the fertility of La Mata's soil.

The término was divided into many plots, very irregular in shape, scattered higgledy-piggledy across the rolling fields. The biggest plots were one of nine fanegas (four hectares) belonging to the town council and one of eight fanegas of the parish church. Altogether the catastro listed 551 arable plots and 33 meadows, which means that the average size of the first was under two fanegas and of the second hardly one. The larger holdings did not consist of larger plots but only of a greater number of them. As was common practice under such a system, the término was divided into several large fields (hojas ), and all the plots in each field were sown and harvested in the same year. In the late spring, the landscape of La Mata and its region would alternate between large patches of rippling green and others of fallow red and brown earth.

The scene had not always been so neat. Records preserved from earlier times suggest that prior to the population expansion of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when much of the region was still waste and available for pasture, farmers planted and harvested their individual plots as they wished. As more of the land of a community was put under the plow, an arrangement had to be made to feed the livestock: draft animals and sheep, both essential to the local economy. The solu-

[7] The data on the Armuña region refer to one of the geographic zones into which I divided the province for analysis (see Appendix Q). The data come from an analysis of the provincial returns of the catastro, AHN, Hac., Catastro, Salamanca, libros 7476, 7477, 7478, in each volume under letra D, "Producto de cada medida de tierra en reales de vellón."

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tion in the fertile grain regions of Castile, which could produce wheat regularly, was to establish large fields within each término, alternating between a year of grain and another of fallow, half the fields in one cycle and half in the other. After the summer wheat harvest, the fields would lie untilled through the winter, and the animals would pasture on the stubble (rastrojo ) and weeds. Fallow plowing followed in the spring, to renew the soil and retard evaporation, until time for the autumn sowing of the next wheat crop. Henceforth all farmers of a village had to follow the same pattern, called familiarly año y vez, but each farmer needed to have plots scattered through all the hojas in order to equalize his harvest.[8]

The information in the catastro provides an easy estimate of the annual harvest of La Mata, since it includes the number of fanegas there were of each quality of land and the size of crop each quality produced annually per fanega. The latter figure was obtained by halving the expected harvest because each plot was sown only every other year (Table 7.2). These figures can hardly be expected to be exact. The makers of the catastro did not survey the plots but had to accept the best estimate of their size, and it was a matter of judgment into what class of land they

[8] García Fernández, "Champs ouverts," 705–9.

assigned each plot, since there was a continuum in the quality of the soil from the poorest to the best.

A more reliable measure of the harvests is provided by the tithes (diezmos ) reported in the catastro for the five-year period ending in 1752. In describing the different plots, the catastro defined them as being planted in either wheat or rye, but in fact the tithe returns show that the farmers also planted other crops, barley, oats, algarrobas (carob beans), and garbanzos (chick-peas). The farmers paid one-tenth of their harvest of all these crops as tithes.[9]

The tithes fell into three categories. The larger part were lumped together for distribution to those institutions that were entitled to a share of the town tithe fund, the cilla . These were known as the divisible tithes, or partible . The property of certain religious institutions was exempt from tithes, and the owners required the tenants who farmed these lands to pay them a substitute for the tithes. These payments were called the diezmos privativos, or more commonly the horros, from the expression horro de diezmos, exempt from tithes. Rather than a stated proportion of the harvest, the horros were a fixed payment, such as some proportion of the rent, and were usually less than a full tithe.[10] The property of the benefice of the parish church (emolument of the priest), of the fabric (building and maintenance fund) of the church, and of a monastery and two convents in Salamanca enjoyed this privilege.[11] Finally, by a special concession, the cathedral of Salamanca received for its fabric the tithes of the fourth largest tithe payer of each parish in this region, the cuarto dezmero .[12] The horros were paid into the tithe fund, which then distributed them to the owners of the land; the tithes of the cuarto dezmero, however, never entered the tithe fund but went directly to the cathedral.[13]

The catastro recorded the average amounts collected in tithes from 1748 to 1752 shown in Table 7.3. The total harvest indicated by the reported tithes has about 17 percent more wheat and 41 percent more ryethan estimated in Table 7.2 from the size and quality of the fields and

[9] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 15.

[10] See Archivo Parroquial, La Mata, tazmía, f. 1, where horros are stated to be 1/10 of the rent of the lands of the benefice of the parish and 1/15 of the rent of other lands subject to horros.

[11] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 15 and maest. ecles., ff. 41, 48, 177 (Convento de Santa Clara), 179 (Convento del Corpus Christi), and AHN, Clero, libro 10668, f. 74 (Monasterio Nuestra Señora del Jesús, whose exemption is not mentioned in the catastro).

[12] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 15.

[13] This information is revealed by the tithe records of the end of the century, Archivo Parroquial, La Mata, tazmía.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

includes other crops as well. I shall consider the figures in Table 7.3 more reliable and proceed on this basis.

To analyze the economy of the town, one must know the combined value of the harvest of all crops. It is possible to state this in reales because the catastro gives the current local prices of each crop, but I shall convert all the crops into their equivalent value in fanegas of wheat on the basis of their prices. The fanega of wheat was the unit in which most rents were paid and a unit that remained constant, whereas prices rose and fell. To make this conversion, one calculates the total value of each crop in reales and divides the result by the price of one fanega of wheat, which at the time of the catastro was fourteen reales in La Mata. Table 7.4 shows that the average total harvest of the town was equivalent in value to approximately 4,186 fanegas of wheat (hereafter the abbreviation "n EFW" will be used for "equivalent in value to n fanegas of wheat").[14]

Information provided by the records of the nearby village of Villaverde, which will be studied next, shows that it was the custom in this region for a farmer who tilled lands outside the limits of his town to

[14] See Appendix N on the use of EFW as a unit of value. Le Roy Ladurie agrees that grain is a more reliable medium than gold or silver to measure purchasing power in the early modern period (Paysans de Languedoc, 28).

divide the tithes on the crops from these lands evenly between his parish's fund and that of the parish in which the harvest was grown. If the harvest of vecinos of neighboring villages on fields inside La Mata was the same as that of vecinos of La Mata from land they farmed outside the town limits, then the two balanced out, and the harvest indicated by the total tithes represents the gross harvest of La Mata farmers; but if one harvest were greater than the other, then the difference between them should enter into the calculation of the total income of the vecinos of La Mata. The catastro gives no information on this question, since it does not say who farmed the plots, only who owned them. One can obtain an answer from the tithe roll (tazmía), which has been preserved for the years 1762–1823.[15] Only after 1791 does this book list the names of the individual tithers and their payments of each kind of crop. For the three years 1800–1802, the average tithes given to other towns by La Mata farmers was 2.7 percent of the total tithes collected; while the average tithes paid to La Mata by outsiders for harvests collected within its limits were 2.0 percent of the total. At that time the balance was slightly in favor of La Mata, but so little that we can omit it from our calculations, especially since the situation might have been different in midcentury.

In order to estimate how much of the total harvest represented net income for the town, one must deduct the various charges against it. First among these was the seed for next year's planting. The makers of the catastro asked how much seed each quality of land needed. From the answers one can calculate the total seed requirements, keeping in mind that each field was sown only every other year. One recalls that the tithe returns showed the wheat crop to be 17 percent more than the catastro figures predicted and the rye crop 41 percent more (Tables 7.2 and 7.3). I shall assume that the seed was equally underestimated and that the requirements should be corrected upward by these proportions, as shown in Table 7.5. The requirements were then 482 fanegas of wheat and 9 EFW of rye. These data can be converted to predicted yield-seed ratios (compare Tables 7.2 and 7.5): 8 : 1 for first-quality wheat land, 7.2 : 1 for second quality, and 6 : 1 for third quality, or 7.2 : 1 overall. For rye it was 9 : 1.

The farmers also had to provide seed for minor crops. The catastro does not say how much, but the approximation will be not far off if we use the same ratio as for wheat, one-seventh of the crop. The minor

[15] Archivo Parroquial, La Mata, tazmía.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

crops were 623 EFW (Table 7.4), so that their seed was approximately 89 EFW. This brings the total seed requirement to 580 EFW, leaving a net harvest of 3,606 EFW.

2

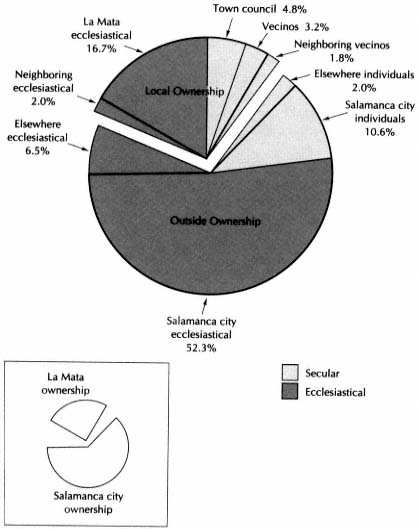

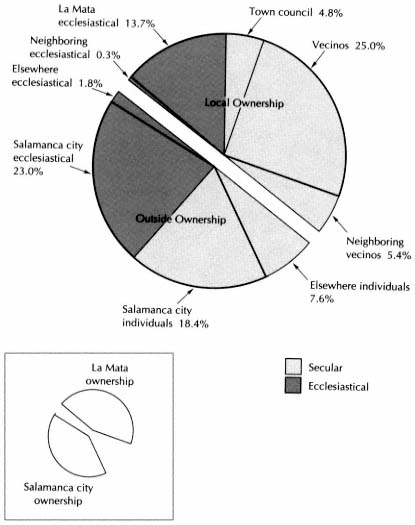

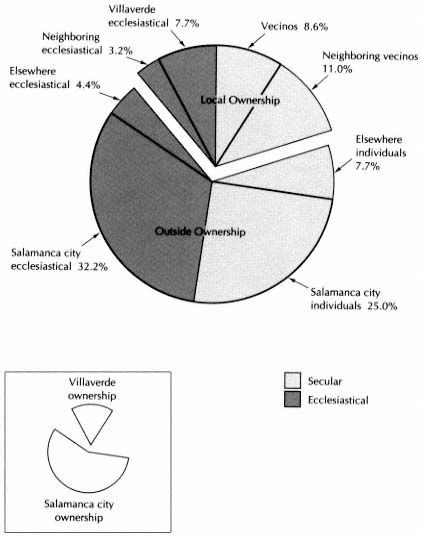

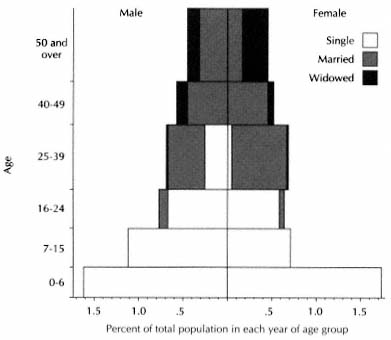

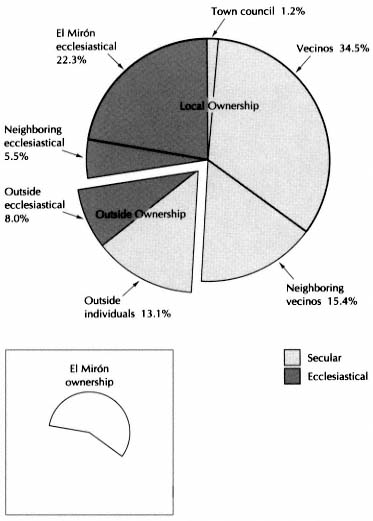

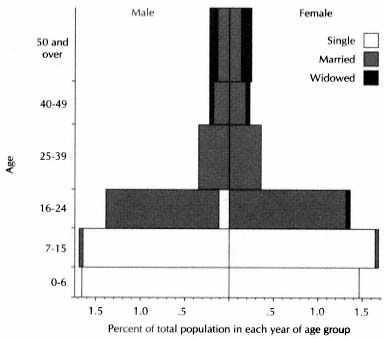

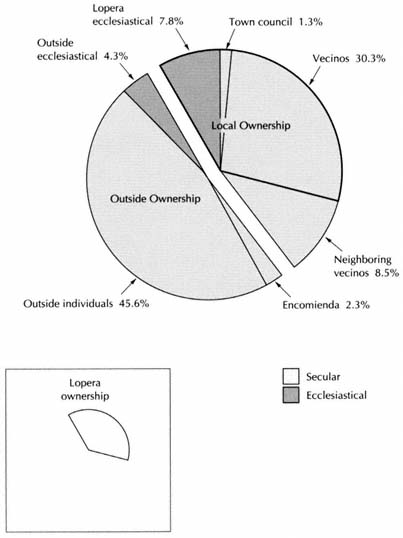

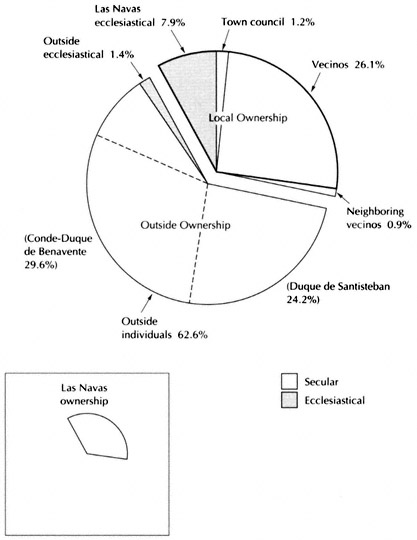

After paying their tithes and deducting their seed, the vecinos had to meet their obligations to their landlords. Although they were blessed by living in the midst of fertile fields, it was their misfortune that very little of the land belonged to them, a condition made dramatically clear by the information in the catastro. By totaling its records of the different properties of each individual and institution, one can determine the amount in the hands of the different categories of owners, in number of plots, in area, and in value. The catastro measured the value of land by the sale price of the average annual crop and the value of houses and

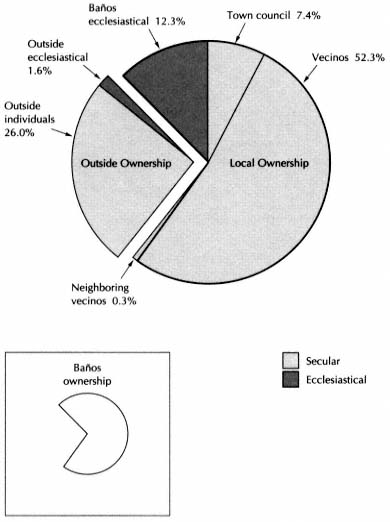

other buildings by their fair annual rent. In analyzing the structure of land ownership, I have used the value assigned by the catastro rather than the area of the holdings as the basis for comparison because it has more economic significance (Table 7.6 and Figure 7.2).

In all, the vecinos, including the priest, owned only 3.2 percent of the land in the town. The vecinos also profited from the propios, council lands that were rented to them to provide town income and were worth more than all the local private property. Adding the property of vecinos of nearby villages who lived near enough to farm themselves, one finds that about 10 percent of La Mata's land was in the hands of local residents. A larger proportion belonged to the benefice and the fabric of the parish, and the four confraternities (cofradías ) of La Mata, while a

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 7.2.

La Mata, Ownership of Land, 1753

small amount belonged to similar church institutions in neighboring villages. Among vecinos, town council, and ecclesiastical funds, about 29 percent of the land by value (it was 31 percent by area) was owned locally, but two-thirds of this belonged to religious institutions.

The situation of the buildings in the town was strikingly different. Of the sixty-two houses, lay vecinos owned fifty-three, the priest, the town

council, and the parish church one each. There were thirteen barns (pajares); lay vecinos owned ten and the priest one. Of the nine corrals, vecinos owned seven and the town council one. Based on value, altogether 91 percent of the buildings was owned locally, but because the total value of the buildings was only 7 percent of that of the land, the property in local hands still represented less than one-third of the total value of all property.

By far the largest part of the land belonging to nonresidents was in the hands of persons and institutions located in Salamanca city, and again the church held the lion's share. Ecclesiastical funds of Salamanca owned 52 percent of the agricultural land in the town. This was divided among the benefices (beneficios ) of two parish priests and four other benefices (capellanías ) attached to parish churches, the fabric of another church, five secondary schools (colegios ) of religious orders, six convents (male and female), two hospitals, and five endowments (memorias ), three in the cathedral and two in convents. An additional 11 percent belonged to individuals, lay and clerical, living in the city. Two percent belonged to individuals located elsewhere, including the Vizconde de Villagonzalo of Valencia. A capellanía of Madrid owned 5 percent of La Mata's land, and a convent in another town in Salamanca province owned 1 percent.

In sum, nonresidents owned 71 percent of the land. Or looking at the situation through the eyes of the statesmen who planned the catastro, religious institutions, both local and outside, owned 78 percent of the land. These were the hard economic facts facing the peasants who plowed and reaped the fields.

How the nonresident owners exploited their land is shown by account books of monasteries and convents in Salamanca that were confiscated when the state dissolved the religious orders in 1837.[16] These provide examples of the agreements between the ecclesiastical owners of land and those who did the actual farming. I have not seen rental agreements of lay owners, but their practices must have been similar if not identical. Contracts were usually signed formally before a notary for six- or nine-year periods, "de tres en tres," meaning that they could be renegotiated at the end of each three-year period. The tenant (rentero ) had to have a third party sign as guarantor of his payments, the fiador, usually another farmer in the town. The tenant agreed to deliver to the owner's granary in Salamanca (or elsewhere) a specified number of fan-

[16] I have used the following account books: AHN, Clero, libros 10653, 10668, 10854, 10869, 10880, 10888.

egas of first-class wheat (trigo candeal) on 15 August of each year, to care for the land, to maintain the drainage ditches, and not to sublet. Sometimes other payments were stipulated in addition to wheat: rye, barley, garbanzos, straw, firewood, and, for Christmas, chickens.[17] Monetary rents were collected for pastures and houses but not normally for arable land. The tenant was also to pay the tithes on the harvest, or the horros in lieu of tithes to those owners whose property was exempt from tithes.

The tenant kept for himself all the harvest over and above the rent and tithes. These were not sharecropping agreements, for the rent was fixed. In a good year the tenant would get a larger share of the total crop than in a bad year. The account books show that tenants sometimes fell behind in their payments, usually as the result of a poor harvest. On such occasions the religious institution usually e xacted no penalty but kept a record of the amount of grain due, which the tenant paid along with the following year's rent or at the next possible opportunity.[18] Sometimes a tenant fell so far behind that his lease was not renewed, "por haberse perdido este rentero";[19] but the standard practice was to renew the lease, usually on the same terms, time after time. When a tenant died, his widow or sons would take over the contract. If the property was more than one peasant could handle, two or more joined to sign the lease, with each specifying the amount he was to pay. This was often the case when the religious institution owned lands in several towns and leased them as a single block.

The account books do not say what share of the average crop was represented by the rent. The catastro states, however, that the usual practice of ecclesiastical owners was to charge as rent a flat rate of 1 fanega of grain for each fanega of land, whatever the quality.[20] This must have been the local rule of thumb in renting land; in the twentieth century absentee owners still calculated the rent of their fields in La Armuña according to their extent, regardless of the quality.[21] A comparison of the property recorded in the catastro and the accounts of three

[17] For example, AHN, Clero, libro 10653, f. 2v.; libro 10668, ff. 50, 113.

[18] In 1802 the Convento de Corpus Christi added 9 1/2 fanegas of wheat as "costas" to the amount owed by two farmers of Calzada de Valdunciel. Their annual rent was 46 fanegas. They were 67 fanegas in arrears in 1799, and their deficit had grown to 97 fanegas in 1802 (ibid., libro 10880, f. 40). In 1803 the lease was renewed. One of the farmers was dropped but the other continued with a new partner (libro 10869, f. 76). This is the only example I observed of a penalty for falling in arrears.

[19] Ibid., libro 10854, f. 11r.

[20] La Mata, maest. ecles., f. 274v.

[21] Cabo Alonso, "La Armuña," 377.

institutions owning land in La Mata indicates, however, that the owners in practice received somewhat less than this rule would provide. The monastery Nuestra Señora del Jesús of nuns of the Order of Saint Bernard owned twenty-four plots in La Mata with a total area of 38.25 fanegas, but the account book shows that the nuns rented the holding in 1751 for 35 fanegas of wheat delivered to their door. In 1777 they raised the rent to 38 fanegas but dropped it to 30 in 1789, where it remained until 1809, when the book says the holding was sold.[22] The convent of La Concepción of sisters of the Order of Saint Francis owned twenty-five arable plots totaling 53.5 fanegas, and one meadow of little value. The rent was 37 fanegas in 1756, raised to 39 in 1781. In 1804, at the height of the great famine, the nuns renewed the agreement for only 33 fanegas, and they were still collecting this amount in 1810.[23] Finally, the convent of Corpus Christi of sisters of Saint Francis owned thirteen plots measuring 16.5 fanegas. Account books for the years 1800 through 1805 show that the rent was 14 fanegas of wheat. The sisters, however, were having difficulty collecting even this much. The tenant was behind almost a half year's rent in 1799. By 1802 the arrears were over three-fourths of a year's rent, they tripled as a result of the disastrous harvests in 1803 and 1804, and at the end of 1805 were still over two years' rent.[24] This was not the only tenant of the convent in such straits. At the end of 1802 it had thirty-one tenants in different towns, of whom nineteen were in arrears. Either the nuns were complacent landladies or they were asking more than their tenants could provide.

In all three cases the owner received less than 1 fanega of wheat per fanega of land. From 1751 to 1776 the monastery Nuestra Señora del Jesús got 92 percent of this figure; from 1756 to 1780 the convent of La Concepción got 69 percent; and from 1800 to 1805 the convent of Corpus Christi asked 85 percent but failed to get this amount. These three cases cover about one-seventh of the land owned by outsiders. Lacking other information, I shall take them as a representative sample of both secular and ecclesiastical owners and use the figure 0.8 fanega of wheat as the best estimate of the rent for each fanega of arable land, whether used for wheat or rye. The fields owned by outsiders totaled 718 fanegas, according to the catastro. The annual rent for these would then

[22] AHN, Clero, libro 10668, ff. 74, 100; La Mata, maest. ecles., ff. 152–63. The account book speaks of twenty-two tierras in 1803. Had the nuns sold two plots in 1789, when the rent went down? Religious institutions did not often sell their land.

[23] AHN, Clero, libro 10854, f. 24; La Mata, maest. ecles., ff. 164–77.

[24] AHN, Clero, libros 10880, 10869, f. 91; La Mata, maest. ecles., ff. 179–89.

have been roughly 575 fanegas of wheat. One can calculate that the expected harvest on these fields would be 2,547 EFW, so that the rent amounted to 23 percent of the harvest.

In addition, the vecinos would have rented the fields in the town belonging to the churches of La Mata and neighboring parishes. These totaled 172 and 25 fanegas respectively, and the rent on all of them would have been about 158 fanegas of wheat.

Two minor payments to the church completed the charges on the farmers. In addition to the tithes, people who grew more than meager harvests had to contribute first fruits (primicias ). These consisted of 0.5 fanega of each crop from every farmer who harvested at least 6 fanegas of that crop, and the annual average of first fruits was 27 EFW. Farmers in Castile paid also the Voto de Santiago to the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in fulfillment of a legendary vow to the saint made by the ninth-century King Ramiro of León at the battle of Clavijo. Every farmer liable for first fruits contributed to the voto 0.5 fanega of his best grain ("de la mejor semilla que coge media fanega"). In La Mata twenty-eight persons together paid 12.5 fanegas of wheat, 1 of algarrobas and 0.5 of garbanzos, or 14 EFW.[25]

3

Besides their harvest, the farmers drew income from raising various kinds of livestock. The number of animals and the selling price of their young are given in the catastro. Those born each year would represent income for their owners and for the town, whether they were slaughtered for food or sold at outside markets, except for those animals, particularly draft animals, that replaced ones that died. One can estimate the number born annually as somewhat less than would be expected today and the life span also less because of poorer nutrition and medication. The process is described in detail in Appendix K, and the calculation for La Mata is worked out in Table 7.7. It shows that the income to the vecinos from livestock was approximately 4,946 reales, or 353 EFW. The vecinos also raised an unstated number of chickens, but since they sold for 1 real each, their total value could not have been much.

From the total income from their animals the vecinos had to pay the cost of pastures. Outsiders owned meadows that according to the catas-

[25] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 15.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tro produced 40 reales per year; one can consider this their rent. Local churches owned others that brought in 8 reales. Half the year the vecinos pastured their animals in the town and half outside, probably in adjoining despoblados.[26] Within the town the vecinos had the right to graze their livestock on the meadows of the town council and after the day of San Juan, 24 June, on all private meadows, but the town council charged them 500 reales per year for the use of these meadows even though it was considered a common right.[27] One may assume that for the half year that the herds were pastured outside the town the vecinos paid more, perhaps 750 reales. Pastures thus cost the vecinos 1,300 reales per year, 93 EFW, but the town economy lost only the amount paid to outsiders, 800 reales or 57 EFW.

By assembling all this information, one obtains an estimate of the net income of the vecinos from agriculture. One must keep in mind that its reliability depends on the accuracy of the data provided by the catastro. Table 7.8 summarizes the information. The total net income of the vecinos from agriculture is 2,682 EFW.

[26] Ibid. Q 20.

[27] Ibid. Q 24.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

4

To give meaning to this figure and to clarify the agricultural economy of this small community, one must attempt to determine how this total net income was distributed among the population. Of the sixty vecinos, twenty-two, including two widows, were engaged in agriculture. Except for a mule herd (guarda de ganado mular ) and a warden of the fields (guarda de campos ), whose task would have been to keep the livestock off the crops and watch them when they were pasturing outside the town, all the others of this group were described as husbandmen (labradores) or day laborers (jornaleros), eleven of the former plus two

viudas labradoras, and seven of the latter (Table 7.1). The difference between a labrador and a jornalero was not whether he owned land or not, for only six labradores owned land and one jornalero did, but whether or not he owned a team of animals for plowing. All but one of the labradores owned one or more yokes of oxen (the other owned a pair of horses), while jornaleros had none. Since the word labrador comes from the verb labrar, to plow, possession of a yoke of draft animals was evidently the requirement for belonging to this category. The jornaleros probably worked on the land for a daily wage, as their name implies. In addition, some vecinos who were not labradores raised crops as a marginal source of income. These were called senareros, and the catastro says there were thirteen of them, including, presumably, the jornaleros and guardas.[28]

Of all these people only one could be considered an independent landowner. This was the richest layman in town, Juan Rincón, who had ten oxen and twenty-two other large animals, five arable plots, one meadow, and five houses. He owned half the land belonging to the lay vecinos.[29] He also had the largest household in the village: a wife, a twenty-year-old son, two daughters, and five children not his own called enternados, three boys and two girls, whether children of relatives or charity cases we have no way of knowing. Seven other vecinos and two children owned land, but each had only one or two arable plots or a small meadow. Except for Juan Rincón, all labradores had to rely on lands they rented to provide their livelihood, and even Rincón's fields produced too small a harvest for his family. Like the other labradores, he got most of his crops from rented plots.

The catastro does not say who rented the fields of La Mata, so that one cannot calculate directly the harvest of each farmer. One can approach the problem indirectly, however, from two sets of data, the number of draft animals each farmer had and the individual payments recorded in the tithe records of the end of the century.

According to the catastro, the eleven labradores and two viudas labradoras owned forty-eight oxen and two horses. At the other extreme from Rincón, with his ten oxen, were three labradores and one labradora with two oxen each and the labrador with two horses. Contempo-

[28] Ibid. Q 35. The register of tithes calls the tithers labradores and senareros, or sometimes all jointly cosecheros (harvesters). According to ibid. Q 15, twenty-eight persons raised sufficient crops to pay first fruits.

[29] La Mata, maest. segl., ff. 63–70.

raries calculated that a yoke of oxen could plow 22.5 fanegas per season.[30] Since La Mata sowed its fields every other year, the twenty-four yokes of oxen were theoretically sufficient for 1,080 fanegas, a figure very close to the 1,017 fanegas of arable land reported in the catastro. One can thus hypothesize that the individual harvests of the labradores were roughly proportional to the number of oxen they owned. It is possible that they rented teams to each other or to the senareros in return for goods or services, and this would alter our results some, but the general pattern of land tilled was probably closely related to the number of yokes owned. If one assumes that two horses were equivalent to one and a half oxen, and that the senareros each averaged the share of one-half ox, the total net harvest (2,422 EFW, Table 7.8) can be divided into fifty-seven shares, each representing the output of one ox (about 42.5 EFW per ox). These shares can then be distributed among the farmers as shown in Table 7.9.

Labradores with more than one yoke of oxen had to have help to use all their teams regularly. Juan Rincón needed four men besides himself, and the others with more than two oxen needed another eight men (assuming the labradores with five and three oxen combined their odd oxen into one yoke and shared it). Only four, including Rincón, had sons in the household fifteen years of age or over. The two widow labradoras had sons above fifteen who could do their farming. The eight remaining hands would have been those of the seven jornaleros and a resident servant (criado ). The wages of these hired hands would have to come out of the net harvests of the labradores. The catastro credits the jornaleros with income of two and a half reales per day for 120 days,[31] 17 EFW. If the wages of eight men are prorated among the labradores with more than one yoke according to the number of their oxen, their net income from farming is shown in the last column of Table 7.9.

These results can be checked by using the tithe register of the end of the century. After 1791 it lists each tither by name and states how much he paid of each crop. It thus permits one to determine with considerable accuracy the relative size of the individual harvests at that time. One should use reports of two consecutive years, when all the fields would have been harvested once, averaging over the two years the percent of

[30] The "Capítulos que deben observarse en la repoblación de Salamanca," 15 Mar. 1791, Nov. rec. VII, xxii, 9, says 22 1/2 fanegas "is what a yoke of oxen can plow [in one year]." Cabo Alonso says that in the nineteenth century a yoke of oxen was needed for each 40 fanegas for a two-year cycle in neighboring Monterrubio ("La Armuña," 382).

[31] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 35.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the total harvest of each year accruing to each farmer.[32] I shall use 1801–2, when crops were plentiful. The first year sixty-seven people paid tithes and sixty-six in the second, but twenty-four of these, many of them women, contributed only small amounts and clearly were not fulltime farmers. On the other hand, two of the richest vecinos did not appear on the tithe roll. One was the fourth tither, the cuarto dezmero, whose tithes went directly to the cathedral. The other was the largest tither, the casa excusada or casa mayor dezmera. In 1571 the pope conceded to the king of Spain the tithes of the most wealthy farmer in each parish. Known as the gracia del excusado, the grant was renewed regu-

[32] The French rural sociologist Henri Mendras holds that ten years, or at least more than one rotation, are needed to determine the profitability of a farm (Vanishing Peasant, 71–72). I use one rotation here, as the only practical time span to deal with individual farmers rather than farms. Later it will become apparent that the harvests of individual farmers relative to each other changed considerably in less than ten years.

larly until the middle of the eighteenth century. During this period the crown gave the administration of the excusado to the church, and it appears to have collected these tithes along with the others. The excusado is not recorded as a separate payment in the catastro returns of the towns I have studied, whereas the cuarto dezmero is identified in that of La Mata. In 1760, however, on obtaining a renewal of the gracia del excusado, Carlos III took over its administration, and the tithes of the casa excusada would no longer have been collected with the rest of the town tithes.[33] Therefore, in establishing the relative standing of the farmers from the tithe rolls in 1801–2, one should posit a tither whose harvest is larger than any listed on the rolls, the casa excusada, and another after the next two, the cuarto dezmero.

The largest three tithers on record for 1801–2 averaged respectively 7.13, 7.09, and 6.88 percent of the total tithes recorded for the two years.[34] I shall project that the casa excusada paid about 7.20 percent and the cuarto dezmero 7.00 percent. (The casa excusada may have had a larger harvest, but I can only estimate a figure from the pattern of those below.) The total harvest was therefore 14.2 percent greater than that represented by the recorded tithes, and each individual's share was correspondingly a smaller percentage than the figures just given. Table 7.10 gives the approximate percentage of the various farmers' shares in La Mata at the turn of the century.

In 1801–2 the number of men engaged in agriculture was twice that of 1753, the date of the catastro.[35] If one assumes that one man harvested in 1753 the share of two men in 1801, one obtains the distribution of the harvest in 1753 shown in Table 7.11, and this may be compared with the distribution calculated from the number of plow teams, as shown in the table.

Despite the differences in detail, there is considerable agreement between the two estimates of the distribution of net income from harvests. Both show three labradores with harvests larger than those of the main body of farmers, and both show about half the farmers cultivating their plots as a marginal occupation. Both agree that the minimum net har-

[33] Nov. rec., II, xii, 3. See Appendix G.

[34] Since the purpose here is to compare the harvests of the different farmers, I have applied the prices of the crops stated in the catastro in order to obtain the total value of the harvest of the town and of each farmer. Prices had risen in the fifty-year interval, and the relative price of the crops may have changed; but since wheat made up about 80 percent of the total harvest, it is not misleading to use the price ratios of 1753 (see Appendix H).

[35] In 1753 twenty-eight people paid first fruits; in 1801, fifty-five did and in 1802, fifty-seven.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

vest of a labrador (first through thirteenth farmers) was about seventy fanegas of wheat. Unless the estimate for the casa excusada in 1801–2 is in great error, no single individual stood out then as the rich farmer of the town, and this fact is reflected in the projected table for 1753. It seems more likely that in fact Juan Rincón had a considerably larger harvest than the others in the way that the distribution based on draft animals indicates, although perhaps not this much larger. On the other hand, the projection is surely more accurate in dividing the lower half of the farmers into two distinct groups and is probably more accurate in showing more inequality among the lower labradores (fourth through thirteenth farmers). Despite Rincón's prominence, both tables lead to the conclusion that no individual or small group dominated the village economy. One had to go down more than half the labradores to get to those who harvested less than a third what Rincón did, even if one adopts the higher estimate of his yields.[36]

In addition to their grain harvests, the farmers profited from raising livestock. They had almost all the oxen, cows, horses, and sheep, about half the pigs, and one-quarter of the donkeys. The estimated income from these was 3,364 reales or 240 EFW (Table 7.7). Against this one should set about two-thirds of the rent of meadows, 62 EFW. The net income, 178 EFW, was 7.4 percent of the total net income from har-

[36] See Appendix I.

vests. If the size of the farmers' herds was proportional to their harvests, then we can predict that the total income of each farmer was about 7 percent more than what he received from farming. The mean of the two estimates of the income from farming plus the estimated income from raising livestock is given in the last column of Table 7.11, which represents the best available estimate of the income of individual farmers.

To translate these incomes into some concept of a standard of living, one must determine the needs of an individual measured in fanegas of wheat. Lacking direct figures, one can approach the answer indirectly from available information on grain consumption in early modern Spanish and other societies. David Ringrose provides information on the grain consumed in Madrid at the end of the eighteenth century. In 1784 a population of about 180,000 needed between 2,000 and 2,250 fanegas of wheat per day, or 4.0 to 4.5 fanegas per person per year. In 1797, a year of high consumption, 200,000 people used 2,570 fanegas a day, 4.7 fanegas per person per year.[37] Bartolomé Bennassar gives figures for Valladolid in the sixteenth century that work out to 4.2 fanegas per person per year.[38] Similar estimates for other parts of western Europe vary widely, from 5.0 fanegas of wheat per person in rural England (a contemporary estimate that a modern historian believes should be lowered to 3.7 fanegas)[39] to as low as 2.3 fanegas in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century.[40] A comparable figure to the Madrid one comes from information on Paris in the 1780s provided by the contemporary scientist A.-L. Lavoisier, which gives 3.8 fanegas.[41]

Although bread was the staff of life everywhere, local agricultural production and eating habits would vary the proportion of bread in the diet, and the Spanish rural pattern was probably more like that known

[37] Ringrose, "Madrid y Castilla," 71–72, 94–96, 121.

[38] Bennassar, Valladolid, 71–72. He estimates 234 liters of wheat per capita per year; the fanega was 55.2 liters.

[39] Deane and Cole, British Economic Growth, 63–65, quotes the estimate of Charles Smith, Three Tracts on the Corn Trade and Corn Laws (1766), of 8 bushels of wheat consumed per person per year in the wheat-growing regions of England. The contemporary bushel was 35.24 liters (0.64 fanegas). A modern English scholar, G. E. Fussel, believes this estimate too high and proposes 6 bushels (3.7 fanegas) as more likely (cited in Deane and Cole, British Economic Growth, 63–65).

[40] De Vries, Dutch Rural Economy, 172, says estimates ran from over 200 kg. to under 100 kg. per person per year (from over 4.6 to under 2.3 fanegas). De Vries also provides the estimate of 105 kg. (2.4 fanegas) for the city of Haarlem in 1733–35 (272 n. 161). A fanega of wheat weighs between 43 and 45 kg. (Porres Martín-Cleto, Desamortización en Toledo, 14–15, says 44–45 kg.; Cabo Alonso, "La Armuña" 112–13, says 43 kg.)

[41] Philippe, "Opération pilote," 60–67: 100,940 metric tons of bread per year for six hundred thousand people.

for Madrid and Valladolid, that is, 4.5 fanegas of wheat per capita per year, than the lower consumption reported for northern Europe. This is also the per capita minimum need of a rural family of four in the eighteenth century, according to the geographer Angel Cabo Alonso.[42] One might imagine, however, that a rural community, doing harder work than an urban population and with food normally more available, would consume more per capita than people in the city. An allowance established by the Mesta for rations for able-bodied rural laborers was 1 fanega of wheat per month.[43] In southern France a similar allowance for rural labor was about 10 fanegas per year.[44] Adult males consumed more per head than a population that included women and children; nevertheless the 12 fanegas per year of the Mesta would have been generous. Let us propose that 6 fanegas of grain (3.3 hectoliters or 270 kilograms) per year, mostly wheat, was an adequate per capita allowance of grain for a population of all ages and both sexes for rural Spain in the eighteenth century.

Grain or bread, while the largest item in the individual budget, would be only part. Other items of food that the vecinos of La Mata produced—pulses and meat—have been counted in calculating their net income. Part of their harvests went to feed their livestock. In addition, however self-sufficient the village was, the peasants needed wine, oil, salt, wood for fuel, probably some additional preserved meat and maybe salt fish, items of clothing, occasionally tools and building supplies; some farmers needed to pay for the transport of their harvest to market or to their landlord's granary. There also had to be what the social anthropologists call a family ceremonial fund, savings to pay the expenses of the formalities and celebrations that marked rites of passage as well as the regular expenditures for religious ceremonies and festivals. One can estimate that the grain consumption for food represented about half the needs of a family. For a normal subsistence, then, a rural community required roughly the equivalent in income of 12 fanegas of wheat per person per year. Although only an estimate, the figure of 12 EFW can serve as a standard measure of adequate individual income, a benchmark against which to compare the conditions in our towns as we proceed. Individual families could, however, do with less, perhaps little

[42] Cabo Alonso, "Antecedentes históricos," 81–82. Cabo speaks of 800 kg. per year as the consumption of a family of four members.

[43] Le Flem, "Cuentas de la Mesta," 64. The exact amount is 1 fanega and 1 cuartillo (1/48 fanega) per person per month.

[44] Le Roy Ladurie, Paysans de Languedoc, 98: 5.6 hectoliters per capita for a travailleur de force.

more than half as much, if they went without sufficient bread, meat, clothing, fuel, and the amenities of life. And if the proportion of infants to adults in a family was high, its per capita need was also less.

From the lists of families in the catastro, one can know the average size of households in La Mata. Of labradores' households where both parents were alive, this was 5.1, of jornaleros', 3.6. The labradores not only had more children (2.6 per family compared to 1.6) but Juan Rincón's five enternados added to their average. At 12 EFW per capita, household needs averaged about 60 EFW for labradores and 43 EFW for jornaleros. The two viudas labradoras had an average household size of 4 and needed 48 EFW each. According to Table 7.11 the top thirteen farmers whose net annual income ranged down to 75 EFW had more than enough for their family needs. These would have been all eleven labradores and the two viudas labradoras. The five labradores whose net income was 190 EFW or more were prosperous, able to hire help, live at ease, and save as well—buying bedclothes, copper and brass cooking utensils, embroidered woolen garments, and amassing coins and jewelry. The large filigreed gold and silver buttons and necklaces of the Salamanca charro are famous and in a pinch would be readily exchanged for money by a cambiador at a rural fair.[45] The next four labradores, with net incomes of 105 to 140 EFW, if not wealthy, were comfortably off, and the remaining four, at 75 to 85 EFW, easily had enough for their needs. The remaining fifteen farmers were in the 20 to 30 EFW range, not enough by itself for the average family; they either were engaged in other activities as well—as senareros whose main activity was not agriculture or as jornaleros who also had wages—or were incomplete families. If the jornaleros did earn the 17 EFW with which the catastro credits them, they had enough for their households, between 3 and 4 in size., to live adequately. On the whole Ceres was kind, even generous, to the vecinos of La Mata who tilled the fields.

5

Many vecinos were not farmers, however. The district of La Armuña was one of the few in Castile that had a sizable number of muleteers, or arrieros, and La Mata, with twenty-three, had the highest proportion of arrieros among its vecinos of any town in La Armuña. Some specialized

[45] On the rural custom of putting savings into gold and silver jewelry and exchanging it for cash at rural fairs, see Fernández de Pinedo, "Actitudes del campesino," 377–78.

in the transport of local grain to nearby markets, Salamanca, Zamora, and other provincial centers,[46] while others traveled regularly on a northern route to Vitoria and Bilbao, taking wheat and bringing salt and salt cod on the return journey.[47] Among them they owned 18 mules and 152 donkeys, most of which they used in their trade.[48] The makers of the catastro estimated that each arriero worked two hundred days per year and earned 1 real per day with each donkey and 2 with each mule.[49] At this rate their total gross annual income would have been 37,600 reales, but the figure arrived at by the makers of the catastro was 33,200 reales (2,370 EFW), after allowing for animals declared not in service.[50]

Against this income, the arrieros had to charge the expenses of feeding their animals and replacing those that died. They probably occupied the pastures available to the vecinos not being used by the farmers. This represented a cost of 31 EFW. Since the animals were on the road over half the year, they also had to pay for pastures where they went.[51] These may have cost them another 75 EFW. In addition, they had to supply fodder, which they would buy since they had few crops of their own. They may have consumed a quarter of the fodder grown locally and bought an equal amount on their journeys. Barley and algarrobas were the local crops for feeding livestock; a quarter of the local production was 121 EFW (Table 7.4), so that the arrieros spent about 240 EFW for fodder. The total cost of feeding their animals was then some 345 EFW.

Owning three-quarters of the donkeys in the town, the arrieros raised those they needed to replace the ones that died, but they would have to buy a couple of mules a year from the farmers for about 550 reales.[52] Their net gain on breeding donkeys was about twelve animals (because they used their animals for traffic, they would not have bred as many young as was possible), or 240 reales.[53] Some arrieros, the catastro tells us, also traded in mules, and together they had about 800 reales a year income from this activity. Their net balance from raising and dealing in livestock was about 500 reales, or about 35 EFW.

[46] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 32.

[47] Cabo Alonso, "La Armuña," 126–27. For salt, see Klein, Mesta, 23.

[48] La Mata, maest. segl., shows this many owned by arrieros. La Mata, resp. gen. Q 32, says 136 donkeys and 8 mules used for transport.

[49] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 32.

[50] AHN, Hac., libro 7476, letra F, f. 108.

[51] The oxen of the Cabaña Real de Carreteros (Royal Association of Carters) had the privilege of grazing free on pastures along highways, but this did not extend to muleteers (Ringrose, Transportation, 104).

[52] A young male mule was worth 200 reales, a young female mule 350 reales (La Mata, resp. gen. Q 14).

[53] See Appendix K.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Adding income from traffic and livestock and subtracting the cost of feed, the balance of the arrieros was 2,060 EFW. They had their costs of doing business, but these can be considered part of their cost of living, like tools in the case of the farmers.

The number of animals each arriero owned was a measure of his relative income, with one mule bringing in the equivalent of two donkeys. The arriero with the most animals owned two mules and eleven donkeys (but he declared only ten donkeys in use), the man with the fewest had four donkeys (but said he worked with only three). Calculating an annual income equivalent to 12.5 EFW for each donkey and 25 EFW for each mule declared in service, one obtains the net income of the individual arrieros shown in Table 7.12, between 37.5 and 175 EFW per household.

The average size of the families of the arrieros was 3.5 virtually the same as those of the jornaleros. Forty-two EFW would supply each family adequately. All but one of the arrieros earned at least this much, and this man did not declare one of his donkeys in service and thus may have understated his income. Although as a group they were not so well-off as the labradores, the top third could live comfortably and have money to save.

Fewer men were engaged in services and crafts. The most respectable was the "surgeon-bloodletter," whose annual income was seven hun-

dred reales (50 EFW).[54] Less distinguished but better off was the tavernkeeper, who also acted as farrier. In the role of tavernero he made three hundred reales from the sale of wine and one hundred reales from groceries, while as herrador he was judged to earn three reales a day, say six hundred a year.[55] His income was 65 EFW. There was also a schoolmaster, but the catastro fails to record his income. The two artisans were a linen weaver, assigned three reales a day for 100 days work per year, and a shoemaker, at two reales a day for 120 days.[56] These convert to only 21 and 17 EFW, not enough to live on (they had three and four members in their families, respectively), so that these two men must have been among the senareros, who farmed part-time. The linen weaver acted as town record keeper (fiel de fechos) and received eighty reales for the job.[57] Crafts were obviously a marginal occupation in La Mata. Indeed one labrador was also a tailor, but no income is recorded from this activity;[58] while one man, evidently the son of an arriero, acted as a blacksmith (herrero ). He was paid in wheat for shoeing the oxen—twenty-two celemines (1 5/6 fanegas) for each ox—and earned 45 EFW this way. The cost of renting the smithy from the town council, 6 EFW, and of buying coal, 19 fanegas paid in kind, rendered his net income 20 EFW, a marginal sum.[59]

Farming and transport were the major activities of the town, and those engaged in them were the better-off members of the community. Except for one person, that is. Among the wealthiest men in the town was the priest, don Juan Matute. Part of his wealth was personal, patrimonial as it was called; for he owned six arable plots and a house and barn, more than Juan Rincón, the richest layman. In addition he received the income from his benefice. Fifty-five plots that measured 117 fanegas belonged to it. Most probably don Juan did not farm himself but collected the rent from both his own fields and those of the benefice, at an average rent of 0.8 fanega of wheat per fanega of land a total of 102 fanegas of wheat.[60] The property of the benefice was exempt from tithes, so that the horros went to him, 36 fanegas (Table 7.3). Finally, as beneficiado he received one-third of the partible tithes and two-thirds of

[54] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 32.

[55] Ibid. QQ 29, 33; AHN, Hac., libro 7476, letra F, f. 108.

[56] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 33, and AHN, Hac., libro 7476, letra F, f. 108.

[57] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 32, and AHN, Hac., libro 7476, letra F, f. 108.

[58] La Mata, maest. segl., f. 61r.

[59] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 33, and libro personal de legos. The name recorded is Felipe Pablos; no vecino has this name. Francisco Pablos was an arriero; we do not have the first name of the twenty-four-year-old son of Geróonimo Pablos, the poorest arriero.

[60] La Mata, maest. ecles., ff. 8–41.

the first fruits,[61] and these amounted to 131 and 18 EFW (Table 7.3). His gross income was then 287 EFW. Out of this he had to pay one-third of the expenses of collecting and storing the tithes, including the salary of the cillero (tithe collector)—in 1800 these were 300 reales—rent of the granary, and incidental expenses including refreshments (refrescos ) distributed on the day the tithes were paid. The benefice's share of these expenses in 1800 was 142 reales.[62] At current prices this was about 3.3 EFW,[63] but probably salaries and rents had risen more slowly than prices, so that the cost was perhaps 6 EFW in 1753. Don Juan's net income was then about 280 EFW, at the level of the top labradores, but he most likely had additional undeclared income in the form of compensation for conducting individual services—baptisms, weddings, burials—that one cannot calculate. He lived with a boy servant aged sixteen and a girl servant and a nine-year-old nephew, whom he was probably rearing to become a priest, as was a common obligation of Spanish rural curates in the eighteenth century.[64] No doubt he was expected to perform acts of charity, but the regular expenses of the church were cared for by the fabric and. various endowments. His economic standing supplemented his religious curacy to make him the leading figure in the town, a position symbolized by the appellation "don," to which he alone of the villagers was entitled.

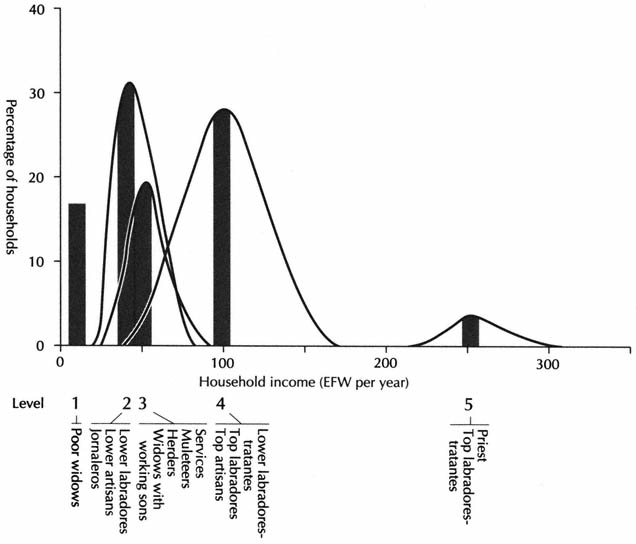

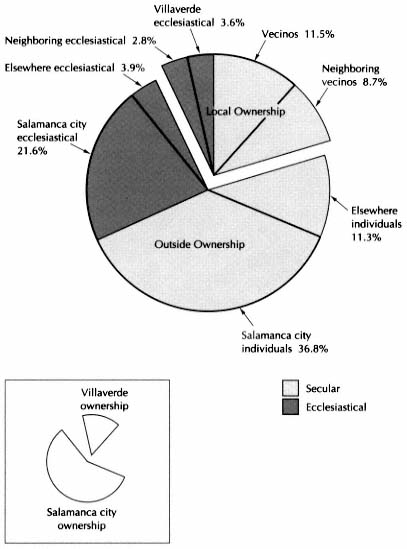

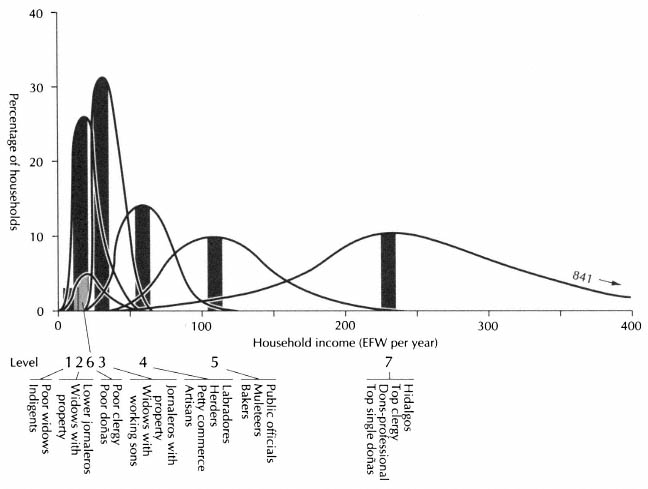

This occupation-by-occupation survey shows the relative position of the different vecinos and points up those who were most wealthy. It can be tabulated in schematic form in a "socioeconomic pyramid" (Table 7.13 and Figure 7.3). Its calculation is based, however, only on income that can be identified in the catastro and tithe rolls. Within the town many payments were made and goods exchanged of which there is no record. Someone, the catastro does not say who, earned three fanegas of wheat and forty-four reales as sacristan;[65] someone else was cillero (keeper of the tithes) and earned perhaps 15 EFW for his services. Poorer vecinos performed services for the richer ones, children did tasks for their neighbors, the town council paid men to perform the public work of the community, and gifts changed hands. The church gave charity and spent money that ended in the pockets of vecinos. Widows were not

[61] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 15.

[62] Archivo Parroquial, La Mata, tazmía (1800).

[63] In 1800 the average price of a fanega of wheat in Salamanca was 43 reales, based on thirty-six weekly returns in the Correo mercantil.

[64] La Mata, personal de eclesiásticos. On rural priests rearing their nephews, see Richard Herr, "Comentario," 276.

[65] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 25.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 7.3.

La Mata, Socioeconomic Pyramid, 1753

Note: This is a bar graph based on Table 7.13, with an indication

of dispersion. It is not a set of frequency distributions.

destitute, although no income can be assigned them. To complete the economic picture of the town and judge its overall well-being, one may look at it as a single unit rather than as a collection of discrete households and consider it in relation to the outside world.

6

The income of the town as a separate economic unit came from its agricultural production and the value added to goods and services it sold

outside. The net harvest after deduction for seed was 3,606 EFW, the gross income from livestock 353 EFW (Table 7.8). The arrieros brought in most of the income from outside. While they transported some of the local harvests and brought in goods, most of their services were rendered to others. It seems reasonable to attribute 75 percent of their gross income from haulage (2,370 EFW) to outside sources: 1,780 EFW. If three-quarters of their income from trading mules also came from outside, this was another 43 EFW. It is possible that the linen weaver and the shoemaker sold some goods outside the town, but their incomes were so small that they hardly added to the total.

Against these incomes one must charge the payments made outside the town. These included rent on the fields owned by nonresidents, on pastures in adjoining despoblados, and on pastures used by the arrieros while on the road, as well as the cost of the fodder they bought while traveling, all of which have already been calculated. It was likely that vecinos of La Mata and its church owned as much land in neighboring towns as vecinos and churches of those villages owned in La Mata, so that rent received from nearby farmers would offset the rent paid for land in neighboring towns (about 23 EFW). This amount can be subtracted from the rent paid outsiders (575 EFW; Table 7.8), while none of the rent paid to local churches will be charged against the town.

A good proportion of the payments to the church also left the town. Two-ninths of the partible tithes of Castile had been granted to the king by the pope in the thirteenth century. Known as the tercias reales, the grant was extended to all Spain and made permanent in 1487.[66] In La Mata and other places around Salamanca, these now went to the University of Salamanca by royal cession (87 EFW, Table 7.3). In addition another third of the partible tithes (131 EFW) belonged to the prestamo, a form of ecclesiastical perpetual right, whose current holder was a member of the faculty (maestre de escuela ) of the university.[67] These beneficiaries had to pay their share of the cost of collection and storage of the tithes, and this expense remained in the town economy. The holder of the prestamo was also entitled to one-third of the first fruits (9 EFW), while, as described earlier, various institutions received horros in lieu of tithes on the crops of their fields, the tithes of the cuarto dezmero went directly to the cathedral, and the Voto de Santiago to the archbishop of Santiago de Compostela through his local agent. After the local benefice took its third of the partible tithes, the local fabric received the remain-

[66] Desdevises, L'Espagne 2 : 369.

[67] La Mata, resp. gen. Q 15.

ing ninth.[68] Besides the tithes of the villagers of La Mata, its church also received those of the neighboring despoblado of Narros, which was an anexo of the parish. These totaled 97 EFW[69] and had the same destination as the partible of La Mata: five-ninths left the town. A good part of the ninth paid the fabric as well as the rent of the fields belonging to the parish church (exclusive of those of the benefice) must have been spent outside the community for supplies for the church and religious services, perhaps 25 percent (28 EFW).

Finally the village as a civil unit met specific annual impositions. Fifteen fanegas of wheat went to the city of Salamanca as La Mata's obligation under a foro perpetuo, a form of feudal dues.[70] The village also paid one fanega of wheat to the convent of Calced Trinitarians of Salamanca, "they do not know for what reason."[71] Then there were royal taxes, thirty reales (2 EFW) for the servicio ordinario y extraordinario y su quince al millar (a direct levy consented to by the Cortes of Castile under the Habsburg kings, for which most towns had since compounded at a fixed annual payment [encabezamiento]) and five hundred reales (36 EFW) for sisas, an excise tax on certain consumer goods that had also been compounded for and that the tavernkeeper now paid for the town.[72] The payments made by the town council could be met by the rent on its buildings and fields.

From this information one can strike a balance for the net annual income of the community of La Mata, as done in Table 7.14. The figure is 4,683 EFW.