PART THREE

SELF-DEFINITION IN HELLENISTIC ART

Introduction

Andrew Stewart

Hellenistic consumers of what we now call "art" lived in a society that was riven with internal tensions. Alexander had changed the Greek world forever, but the polis was still there; its norms were still intact and its institutions still functioned. Even its most treasured possession, its political freedom, was often explicitly guaranteed by the kings who had now inherited Alexander's legacy of empire. Yet such guarantees only showed how much things had changed since the fourth century: as Aeschines observed, even during Alexander's own lifetime, the Greek poleis were now beholden to the victor and subject to his whim (3.132-134). Demetrios of Phaleron put it even more harshly: Lady Luck had given the Macedonians the whole world, until such time as she decided to change her mind (Polybius 29.21.1-6).

Hellenistic art registers this state of affairs in a number of ways. Archaic and Classical Greek art had developed their characteristic forms in the service of the independent polis, and its genres—the temple, the athlete statue, the gravestone, the votive relief or picture, and so one—were closely bound up with the polis's needs. Now, not only did the sheer extent and diversity of the Hellenistic kingdoms have a fragmenting effect upon the hitherto fairly unified traditions of architecture, sculpture, painting, and the minor arts, but the appearance of new patrons, from kings and courts to half-Hellenized Levantines or Bactrians, encouraged the appearance of new, often diametrically opposed, modes and styles. Finally, to compound the confusion, the fourth-century masters had already achieved such a daunting command of ways and means that many traditional genres were now all but closed to further development.

The papers of Professors Smith and Zanker, and Professor Ridgway's

response to them, assess the impact of this situation upon two classes of Hellenistic sculpture, the portrait and the gravestone. These were public monuments, a context in which the self-image of Hellenistic men and women was most self-consciously developed and presented. In keeping with recent thinking in the history of art, these papers do not ask how this or that aspect of Hellenistic self-awareness, achieved elsewhere by another process, is reflected in the works they address. Instead, they treat these portraits and gravestones as cultural forms in their own right, as loci in which and through which Hellenistic men and women came to understand and cope with the circumstances in which they lived. Using literature and inscriptions alongside the monuments, they introduce us to that rich constellation of practices and artifacts which the Hellenistic world developed in order to codify, perpetuate, and project its ideas and its values.

Professor Smith's paper begins by reminding us of two crucial developments in late Classical culture: the increasing separation of roles in the citizen body of the polis, and the simultaneous elaboration of visual languages of dress, coiffure, gesture, and posture that could speak to these roles. Yet in the early Hellenistic cities, these languages have to include not merely the traditional citizen audience in their address, but another: the kings and their friends. Philosophers and orators take on the roles of defenders of the polis and standard-bearers for its values, and their portraits increasingly come to register their self-importance in these roles. Meanwhile, the kings develop a language of power, one based on forms that had long been traditional for divine or heroic beings, but now incorporating subtle distinctions that identify them as "first, last, and in the middle, the most excellent of men" (Theokritos 17.3-4).

Juxtaposed in city squares or sanctuaries, as they so often were, the two iconographies must have had a much sharper effect upon the observer than, seen in isolation, they do today; opinions would be polarized and ethical distinctions reinforced. Further work in this field might profitably focus on the ongoing effects of such lack of closure, taking what historians of sculpture have hitherto tended to see only as internal stylistic or iconographic developments, and rethinking them as products of the tensions generated by the continuing tug-of-war between these two poles of Hellenistic society.

Professor Zanker's paper returns us to the immediate confines of the polis proper, tackling two interrelated and oft-debated issues: the existence of local schools of sculpture in particular regions or cities, and the existence of local cultural traditions. In the case of Hellenistic Smyrna, he shows that the one predicates the other: that certain local cultural norms were sufficiently powerful to invite concretization in the city's fu-

neral monuments, and sufficiently distinctive to enable us to read them at two thousand years' remove.

The value system that he disinters shows not only considerable continuities with the Classical period but also a considerable degree of adaptation to the realities of life in the Hellenistic; the reliefs themselves mix tradition and novelty to present us with an intriguing picture of a society that is deeply conservative and self-conscious about the image it projects, in death as in life. (In a welcome aside, Professor Zanker remarks that the virtues these reliefs celebrate are civic, not class virtues; this is not the bourgeoisie alone that speaks in these monuments, but the whole polis collective.) Yet such conservatism is not total and unalloyed: women, for example, are dressed in the up-to-date fashions that identify them as sex objects par excellence, even while their poses and gestures remain eloquent of feminine modesty and decorum. The epigrams, too, offer a counterpoint—perhaps even a safety valve—to the overall self-repression of the images, in their open evocation of personal grief and pain.

Professor Ridgway offers further nuances to both of these papers. She correctly remarks that the situation vis-à-vis the gravestones is more complicated than one might think: dates are insecure and distribution not quite as tidy as appears at first sight. In addition, she emphasizes one more distinctive feature of the stelai: their borrowings from the repertoire of Classical and Hellenistic votive reliefs. They thus emerge as quasi votives to the dead, and on this plane link up With a class of monuments that are amply attested by inscriptions but have almost totally vanished today: the free-standing naiskoi with statues of the dead in the guise of Hermes, Demeter, and other gods and heroes before which cult was offered to the dead.

She further notes that the issue of the superhuman also obtrudes into the territory covered by Professor Smith's paper, and produces instances in which the fault lines between the various genres of public portraiture may not have been so clear-cut as we would like to suppose. As ever, our analysis will have to cope not only with the all but crippling losses we have sustained in the material record, but with the incredible diversity of the Hellenistic world, its variety from kingdom to kingdom, from region to region, from city to city, and last but not least, from person to person.

Kings and Philosophers

R. R. R. Smith

This paper looks at the meanings of different styles of portrait statue in the early Hellenistic period—in particular at portraits of kings and philosophers.[1]

By the later fourth century there had evolved a whole range of portrait styles that could be chosen in order to express a person's position and role in life. It is remarkable with what ease we seem to be able to distinguish, often with no documentation, athletes, orators, philosophers, and kings (fig. 1). I want to look quite simply at how and why this should be so and what roughly it means. What was the purpose of the visual stereotypes we are inclined to take for granted?

First, a word on the functions of the statues and on portrait style. Extrinsically, portrait statues were expensive, imposing, lifesize bronzes that functioned as the most highly valued currency in the benefaction-and-honors system of the Hellenistic city, and we hear a lot about them in literature and inscriptions.[2] Honorific statues were the most important concrete symbols of the honor or time with which cities repaid benefactors. Kings were the most powerful benefactors and so received the most statues—being bronze, however, few have survived. Philosophers received few statues. Some of these were public statues, but probably more were quasi-public, set up in their academies and schools, often at their deaths.[3] We have many major examples (partly) preserved in excellent Roman copies.

[1] I am very grateful to the late P. H. yon Blanckenhagen for discussing this paper with me. It grew out of my work on royal portraits and develops an argument sketched in R. R. R. Smith, Hellenistic Royal Portraits (Oxford, 1988), chap. 11 (hereafter cited as HRP ).

[2] Discussed at length in Smith, HRP , chap. 3.

[3] Public statues: (l) Zeno: Diogenes Laertius 7.6; (2) Epikouros: Diog. Laert. 10.9; (3) Chrysippos: Pausanias 1.17.2 and Cicero De finibus 1.39. Statues in schools: (1) Plato: Diog. Laert. 3.25; (2) Aristotle: Diog. Laert. 5.15, 51; (3) Straton?: Diog. Laert. 5.64; (4) Lykon: Diog. Laert. 5.69.

Intrinsically, a portrait statue expressed key defining aspects of its subject: that is, where he or she stood in the broad scheme of things. This was its visual function. I think that we are now beyond worrying about whether these people really looked like this. The point is they wanted to and no doubt tried to. What we call portrait style is made up of both art and real life. Life contributes the externals of real appearance—beards, hairstyles, clothes. We are all familiar with the potency of these aspects of self-presentation in life. Art simply makes the chosen self-image convincing and coherent.

I am concerned here with the late fourth and third centuries, the heyday of the kings and philosophers. Normal practice has been to treat all the portraits as a single phenomenon and to arrange them in one line of chronological development. There was some formal development in third-century portraits, but more significant, I think we will see, are the different portrait modes that correspond to different historical categories of person. What I want to do is to connect the most important changes and differences to broad historical circumstances, in particular the problematic relationship of the kings and the Greek cities.

In the early Hellenistic period, the Macedonian kings were a new form of political power outside and above the city-states, and a major theme of early Hellenistic history was the difficult relationship between city and king. The relationship was negotiated by a variety of means. The kings used diplomacy and benefactions. The cities offered honors and cults to the king, and their philosophers were tireless in offering free advice to kings in kingship treatises that prescribed correct royal behavior. Most of the philosophers we know about had defined their views on kingship in such a Peri basileias treatise. The philosophers were the city's intellectual spokesmen in its ideological confrontation with the kings.

I want to look first at the range of portraits used by leaders inside the cities, then to look outside, at kings and dynasts, to see what factors and ideas molded the various ways they were represented.

Philosophers and City Politicians

The evolution of portraits in the Classical city can be seen as the creation of image styles for the different kinds of public roles emerging in Greek society. In the fifth century there had been just two main categories: youthful athletes and bearded elder citizens, whether writers or states-

men. Writers and generals, for example, were not essentially different kinds of political being. A striking lack of visual differentiation between poets and generals was recently made plain when a fifth-century portrait type, long thought to be of the Spartan general Pausanias, turned out, in an inscribed example, to be in fact the poet Pindar.[4] This shows how far fifth-century writers and politicians used the same visual identity.

In the fourth century there began major separation of public roles in society, for which were created recognizably different modes—general, orator, philosopher. I look first at the philosophers, then come back to the politicians.

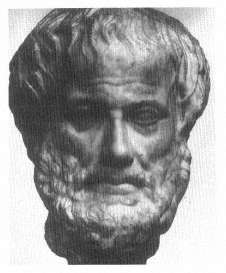

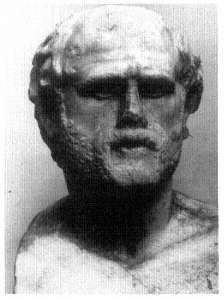

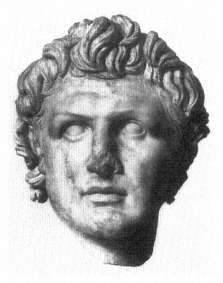

The notion of the man of thought, separate from the executive man, goes back to the portrait of Sokrates. The idea appears partly formed in the portrait types of Plato and Aristotle (fig. 2a)[5] and is brilliantly worked up in the retrospective portrait of Euripides, already in the 330s (fig. 2b).[6] This is a dear representation of the idea, current in the fourth century, of Euripides as the philosophical poet.[7]

The great period of the philosopher portrait was the third century, when it reached its widest range of expression. Instead of placing the relevant heads in a chronological line, it is worth asking what connection the considerable variation of philosophic portrait styles has to the orientation of the different schools. We miss a lot of potential subtlety here due to gaps in our secure identifications. But we can distinguish, I think, two major strands: on the one hand, the Cynic-Stoic image, on the other the Epicurean.

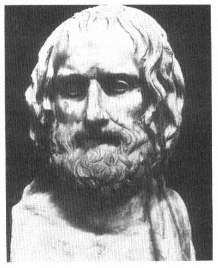

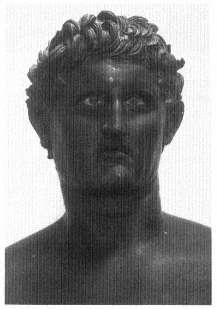

The Cynic is the most typically "philosophic" image, well expressed in the Hellenistic Antisthenes portrait (fig. 2c):[8] long, unkempt hair; straggling beard; crumpled, decaying features—expressive of an ostentatious disregard for vain appearances the better to concentrate on inner thought and moral purity. The Stoic founder Zeno was a radical of this kind, and Stoic self-representation came clearly to be modeled on that of the Cynics.

[4] G. M. A. Richter, Portraits of the Greeks , abridged ed., R. R. R. Smith (Ithaca, N.Y., and London, 1984), 176-180. See now R. R. R. Smith, "Late Roman Philosopher Portraits from Aphrodisias," JRS 80 (1990): 132-135, pls. 6-7; J. Bergemann, AM 106 (1991): 157-158.

[5] Aristotle (Vienna): G. M. A. Richter, The Portraits of the Greeks , 3 vols. (London, 1965), 173, no. 7, figs. 976-978 (hereafter cited as POG ). Sokrates and Plato: Richter, POG , 109-119, 164-170.

[6] Euripides (Naples): Richter, POG , 135, no. 13, figs. 717-719.

[7] Euripides unusually sophos : Plato Respublica 568a and Aischines 1.151; the skenikos philosophos : Athenaeus 4.158e, 23.561a. Gf. L. Giuliani, Bildnis und Botschaft (Frankfurt, 1986), 139.

[8] Antisthenes (Vatican): Richter, POG , 180, no. l, figs. 1037-1039.

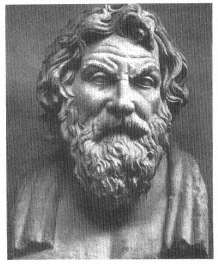

In the portrait of the Stoic Chrysippos (fig. 2d)[9] we have the most developed or intensified representation of this morally uplifting contrast between outer bodily decay and the vitality of the inner mind. More specifically, we may perhaps interpret this as a representation of Stoic pneuma , "vital breath or energy," and its connection with Stoic logos . We are shown that part of the universal mind that was lodged in the mortal sage Chrysippos.

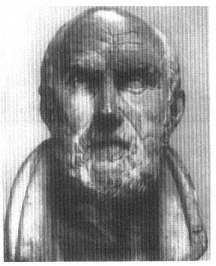

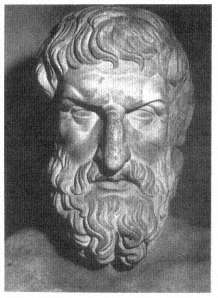

The Epicureans used a quite distinct philosopher style. Two features stand out: good grooming and sameness. First, sameness. The portraits of the three school leaders, Epikouros, Metrodoros, and Hermarchos, cultivated a clearly related image type—a sort of philosophical dynastic likeness (figs. 3a-c).[10] This portrait homogeneity surely reflected both the close-knit or "family" structure of the school and the fixed nature of Epicurean doctrine. Epicurean thought was codified by the founder and remained unchanged to a quite unusual degree.

Second, grooming—a feature of Epicurean appearance noted in antiquity, explicitly in contrast with Stoics and Cynics.[11] The Epicureans have a well-ordered, harmonious appearance, with artfully arranged beards and hair. This is combined with a certain air of distance or hauteur, very different from the more "humble" Cynic-Stoic image. The Epicureans seem less concerned to take an overtly "ethical" stance. The two "Junior" leaders have regular, rather bland features and a kind of placid impassivity which is intended, I think, as an expression of modestia beside the Master. The Epikouros portrait is more vigorous; its aggressive knitting of the brows is a strong ideal element that represents the Master's superior intellectual deinotes .

Next to the philosophers, on the same wavelength, as it were, but further along the band, come the city politicians: the orators and generals. They have shorter, more well-kempt beards and neater hairstyles, and use a more dynamic, outgoing posture, expressive of executive capability. Good examples are the orator Aischines and the general Olympiodoros (figs. 4a-c).[12] They are presented as mature in years but with-

[9] Chrysippos (British Museum): Richter, POG , 192, no. 9, figs. 1118-1120.

[10] Epikouros and Metrodoros (Capitoline Museum): Richter, POG , 195, no. l, figs. 1149-1150, 1153 = 201, no. l, figs. 1230-1232. Hermarchos (Budapest): Richter, POG , 204, no. 16, figs. 1306-1309. See also V. Kruse-Bertoldt, "Kopienkritische Untersuchungen zu den Porträts des Epikur, Metrodor, und Hermarch" (Diss. Göttingen, 1975); B. Frischer, The Sculpted Word: Epicureanism and Philosophical Recruitment in Ancient Greece (Berkeley, 1982); and esp. H. Wrede, "Bildnisse epikureischer Philosophen," AM 97 (1982): 235-245.

[11] Alciphron Epist . 3.19.3. On this and other contrasts between Stoic and Epicurean self-presentation, see esp. F. Decleva Caizzi's paper in Part Five.

[12] Aischines (d. 314) (Naples): Richter, POG , 213, no. 6, figs. 1369-1371. Olympiodoros (active ca. 300-280; portrait known in single copy in Oslo): Richter, POG , 162, figs. 894-896.

out the insistence on aging and mortality seen in many philosopher portraits.

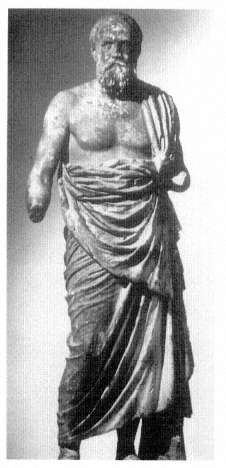

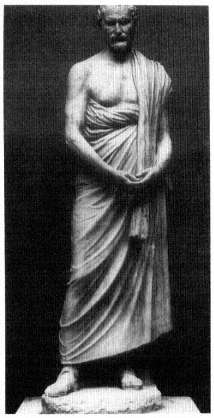

Between the Aischines and the philosophers—that is, in portrait conception—stands the remarkable Demosthenes (fig. 4d).[13] This was a posthumous statue set up in 280, and, with hindsight and probably as a deliberate reaction to the Aischines, it injects into the orator-politician image a whole layer of philosopher iconography. Demosthenes wears a simple himation with no tunic—a clear borrowing from philosopher images (cf. figs. 1c, d). The statue has a plain, "artless," four-square stance and conveys an internalized air, one of troubled introspection. It is a central monument for understanding the visual self-identity of the early Hellenistic city.

Portraits of early Hellenistic city leaders, then, spread across a spectrum from politicians to different kinds of philosophers. A nameless statue in the Capitoline (fig. 1d)[14] provides a full philosopher figure to set at the other end of this spectrum from the Aischines. It was a flabby, aged body, draped in a himation, with a tousled, aggressive portrait head. The figure has bare feet and so is perhaps a Cynic. Although to be read as opposed in this way—well-dressed orator-about-town (Aischines) versus scruffy thinker (Capitoline statue)—the politician and philosopher have things in common, showing they belonged to the same polis environment. They breathe the same civic air. Most important are simple identifying externals, like beards and himatia—these were basic signs of being a city person rather than a royal or court person. They also share some expressive features, like apparently real age and individualizing physiognomies. They are both essentially "ethical" portraits that emphasize the human and moral worth of their subjects.

Kings

From the same time but quite separate are the portrait images of Alexander and the kings (figs. 5, 6). The kings created a quite new mode of portrait image, one that seems designed to express the essentials of their new style of kingship. We may examine its main components as follows: (l) external attributes, (2) the royal portrait head, (3) the royal body or figure.

A royal statue could wear and hold a variety of royal and divine at-

[13] Demosthenes (Copenhagen): Richter, POG , 219, no. 32, figs. 1398-1402.

[14] Richter, POG , 185, figs. 1071 and 1074 (under "Menippos," but unidentifiable).

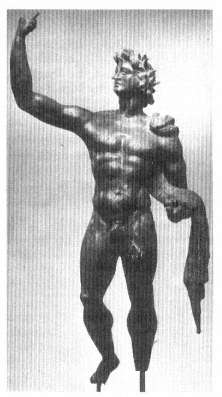

tributes, but generally there is a striking lack of emphasis on regalia. This well reflects the minimal character of Hellenistic royal ceremonial. (There seems to have been very little royal ritual associated with Hellenistic kingship.) A regular attribute of the statue was probably a spear that the figure leans on and holds with an arm raised (fig. la).[15] Originally it had simple military meaning but soon, in this pose, it became a symbol of royal power. It may allude directly to, or represent visually, the important justification of the Hellenistic kingdoms as "spear-won land."[16]

The only invariable attribute of the kings was the diadem, a band of flat white cloth worn around the head. This was not a crown, not an Achaemenid insignia, but simply a Greek headband promoted to take particular royal meaning. Someone invented an etiology for it—that it had been borrowed from the conquering Dionysos and that it symbolized victory.[17] This may represent the official view of its origins. (Dionysos was the most important divine model for Hellenistic kingship and victory its single most important legitimating feature.) The diadem soon became the single exclusive symbol of Hellenistic kingship, and, like many good symbols, it was in origin perhaps empty of precise meaning.

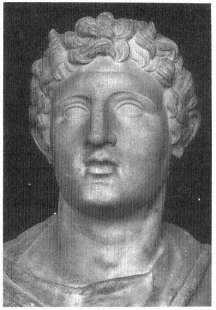

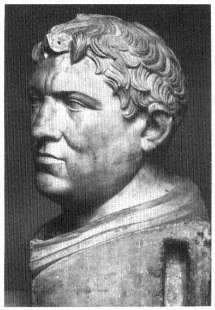

Divine attributes (like the aegis or animal horns) could be used to suggest more specifically godlike status. But they were employed only very sparingly; other, less obvious, less overt means were usually preferred. In the major portrait of Demetrios Poliorketes copied in the herm in Naples, the king wears small bull's horns which state an association with the god Dionysos (fig. 5b).[18] Images of Dionysos himself, however, generally did not wear bull's horns. Demetrios and other kings took the well-known association of Dionysos with bulls and gave it a new kind of visual prominence associated primarily with themselves—that is, the horns refer as much to the king as to the god.[19] The kings thus avoid a

[15] Bronze ruler statuette (Baltimore): D. G. Mitten and S. F. Doeringer, Master Bronzes from the Classical World (Mainz, 1967), no. 132; Smith, HRP , 154, no. 13.

[16] For a thorough examination of this concept, see A. Mehl, AncSoc 11/12 (1980/81): 173-212.

[17] This origin is recorded by Diodorus Siculus 4.4.4 and Pliny Naturalis historia 7.191. See more fully, Smith, HRP , 34-38.

[18] Smith, HRP , no. 4.

[19] It has often been thought that Demetrios' horns refer to Poseidon. The bull-horned and bull-formed nature of Dionysos was, however, much stronger in contemporary minds, especially after Euripides' Bacchae , than bull associations of Poseidon. Poseidon appears on the reverse of coins of Demetrios as a protecting deity of the admiral king, but this does not imply that the horns of the royal portrait on the obverse necessarily refer to Poseidon. In the light both of the powerful Dionysian associations of bulls and bull's horn and of the direct association of Demetrios with Dionysos in contemporary sources (for example, ap . Athenaeus 6.253d; Plutarch, Demetrios 2), a reference to Dionysos was surely the preferred meaning. For Dionysos and the bull, see esp. E. R. Dodds, Euripides: Bacchae , 2d ed. (Oxford, 1960), xi-xxv.

direct divine equation. The horns express not that the king is Dionysos but that he is like Dionysos, or has Dionysos-like powers.

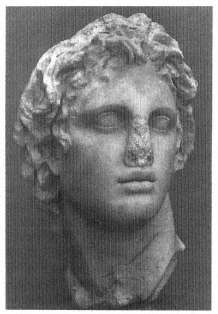

The royal head was modeled broadly on a combination of Alexander and young gods and heroes. It was intended to have a Dionysian éclat: smooth, youthful, dynamic, godlike. The early Hellenistic royal portrait refers clearly to Alexander but is careful to define itself as recognizably different (fig. 5b). Alexander portraits have the longer hair of Greek heroes, like Achilles, and the distinctive anastole of hair over the forehead (fig. 5a).[20] The early kings wear a thick wreath of hair, but it is not as long at the sides and back, and they carefully avoid the anastole , which was Alexander's personal sign.

The same can be seen in the physiognomy. The royal face draws on ideal heads of gods and heroes but is careful to avoid confusion with them, by formal adjustment or by introducing a (more or less slight) layer of individuality. The portraits define the king as like the gods but different. They forge a distinctive royal style.

Oriental influence on the Hellenistic royal image has sometimes been posited. The portraits we have, however, provide no real evidence for "interpenetration." There is little that cannot be explained in Greek terms— either in attributes or in style. For example, bulls horns are found on Mesopotamian images; but they are also used on pre-Hellenistic Greek images. Bull's horns played an important part in Greek terminology about Dionysos,[21] and we should prefer this meaning. Greco-Egyptian royal portraits[22] may seem to be good examples of stylistic interpenetration, but these images, as we can tell from their use of native hard stones and Pharaonic format, were for Egyptian consumption. The influence here is all one way: Alexandrian royal portraits may affect the traditional Pharaonic images of the king, but the reverse is hard to detect.[23]

The third-century royal portrait head had a considerable range of variation, but with clearly definable limits. We may take two aspects: (1) apparent age and physiognomy, and (2) hairstyle.

The king usually looks young or ageless—that is, about twenty to

[20] V. Poulsen, Les portraits grecs (Copenhagen, 1954), no. 31—from or reflecting an Alexander statue of the early Hellenistic period. Most recently on Alexander portraits, see the full study by A. F. Stewart, Faces of Power: Alexander's Image and Hellenistic Politics (Berkeley, 1993).

[21] See Dodds, Euripides: Batchae , xviii.

[22] Full collection in H. Kyrieleis, Bildnisse der Ptolemäer (Berlin, 1975).

[23] Kyrieleis, Bildnisse der Ptolemäer , argues this case, but to this writer not convincingly.

thirty-five, not younger, rarely older. Some kings, especially in the first generation, who were in fact in their seventies or eighties, can use a more mature image but never one near their real age. This was the case, for example, with the two great dynasty founders, Ptolemy Soter and Seleukos Nikator (fig. 5c).[24] In the Naples bronze, Seleukos has a wreath of hair and dynamic posture, signifying "king," and strong mature features, signifying "older king," but he is not near his real age (probably about sixty to seventy) at the time of this portrait.

The limiting case in the portrayal of real-looking features is provided by the nonroyal dynast Philetairos of Pergamon (fig. 5d).[25] He has a dynamic posture but short, flat hair (no diadem, of course) and heavily jowled, "unroyal" features.

Hairstyle Was a highly expressive and important variable in royal portraits. This is especially well shown by the two versions of a head from Pergamon (fig. 6).[26] The head was originally made when the sitter was still merely a prince or dynast, because (although this has not been noticed) it clearly wore no diadem in the first version. Later, a diadem and the thick wreath of hair were added separately, no doubt when he took the kingship. The circumstances well suit Attalos I in the 230s and support the traditional identification of the head as this ruler.

The adjustment dramatically alters the portrait's effect. In the second version it becomes a textbook royal portrait: smooth, ageless features; thick hair; dynamic posture. These express the Hellenistic king's unique status: like a god, like Alexander, but subtly different from both.

The same can be seen in the styling of the royal figure. There were no prerogatives in royal statue types. As far as we can tell the king's statue was most commonly naked, with or without a chlamys over the shoulder. Since both gods and athletes had been shown naked for a long time, this carried no special meaning for the kings. We have few examples, but it seems dear that the kings statue was set off subtly by distinctions of style and posture.

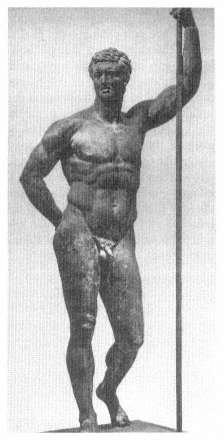

If we compare a high-quality ruler statue, like the Terme Ruler (fig. 1b),[27] and an athlete of comparable quality (lake the Getty bronze),[28] it is extraordinary that with no documentation and with so much in com-

[24] Seleukos (Naples): Smith, HRP , no. 21. Ptolemy: ibid., nos. 46-47.

[25] Philetairos (Naples): Smith, HRP , no. 22.

[26] Attalos I (Berlin): Smith, HRP , no. 28.

[27] Smith, HRP , no. 44. It does not really matter for this purpose whether one thinks the statue a Macedonian prince or a Republican dynast looking like one (so, most recently, P. Zanker, Augustus und die Macht der Bilder [Munich, 1987], 15, fig. 1). I am concerned only with the body type. There are other examples (e.g., fig. la, above), but none of such high quality.

[28] J. Frel, The Getty Bronze (Malibu, Cal., 1982).

mon—nudity and youth—it is still so easy to tell the ruler from the athlete. It is not simply due to differences in pose; this is a matter of body language. The ruler statue borrows the basic figural schemes of the athlete, but adjusts or intensifies their effect. It uses an exaggerated, athletic muscle style as a metaphor of power.

We may return and compare the city elders (figs. 2-4). The kings had, of course, to pay respect to the ideology of ethical kingship that was constantly recommended to them by the philosophers; but, for their portrait image, their visual identity, they had their own concerns: to be Alexander-like, charismatic, godlike. Morality made visual was very much secondary. It is still remarkable that there is a complete lack of significant overlap between portraits of kings and of civic leaders. Each uses exclusive defining elements in both external appearance and style. The kings are naked and godlike; they may wear a chlamys but never a himation; and they are clean shaven. The city leaders, on the other hand, are shown as mortal flesh and blood, seem always to wear at least a himation or chlamys, and have beards. Only four kings, out of well over fifty whose portraits we know, wore a beard.[29]

Some cosmopolitan city-men no doubt shaved, and we have one or two examples, most notably Menander (fig. 3d);[30] but there remains no stylistic overlap, no chance of taking Menander for a prince. We may suspect that many of the kings' adherents in the cities, the locally based Friends of the king (philoi ),[31] would have adopted this manner of self-presentation, but we cannot prove it without sure identifications. We may say that in this respect Menander was clearly presenting himself as a man of the new age. Generally, as far as we can see, the external signs of being a court and royal person versus a city and nonroyal person seem to have been used in an exclusive way. This opposition was played out from head to body. The aging, diffident statue of Demosthenes makes a deliberate contrast with the ideal assertion of power in the naked Macedonian ruler figures (figs. la, b).

Conclusion

The evolution of the third-century city portraits on the one hand, and that of the royal portraits on the other, can each be understood in their

[29] Discussed in Smith, HRP , 46 n. 2.

[30] Menander (Venice): Richter, POG , 231, no. 15, figs. 1573-1576—important version, from Athens, preserving tunic and mantle from the statue. For the reconstruction of the statue, see now K. Fittschen, AM 106 (1991): 243ff.

[31] On royal Friends in the cities, see the study by G. Herman, Talanta 12/13 (1980/ 81): 103-149.

own terms. The city portraits carry on from the fourth century; the royal images are something new. But their exclusive differences also surely reflect the need for a sharper self-definition on either side of the ideological gap between the kings and the cities. In the city portraits, there is a dear stepping up of the human and "ethical" components; and this can be read in some respects as the response of the city intellectuals and politicians to the divinizing, eternally youthful images of the kings. As the kings claimed godlike status, so the cities sought to disclaim it in the portrait style of their leading citizens.

On the other side, for the kings, the realistic, "ethical" portraits of the city worthies contained ideas that they wanted expressly to avoid in their images—infirmity, mortality, a sense of moral struggle. The kings and the city thinkers, in spite of all their efforts at mediation—by kingship treatises and diplomacy—were involved in a basic ideological conflict. It is aspects of this conflict that their separate portrait styles were designed to express.

1. a.

Bronze statuette of ruler, 3d-2d cent. BC (Walters Art Gallery,

Baltimore). Photo: Walters Art Gallery.

b.

Bronze statue of ruler, 3d-2d cent. BC (Terme Museum,

Rome). Photo: DAI, Rome.

c.

Statue of a philosopher, 3d cent. BC

(Delphi). Photo: Phaidon Press.

d.

Statue of a philosopher, 3d cent. BC

(copy: Capitoline, Rome). Photo: Phaidon Press.

2. a.

Aristotle, later 4th cent. BC (copy: Kunsthistorisches Museum,

Vienna). Photo: Phaidon Press.

b.

Euripides, 330s BC (inscribed copy: Museo Nazionale,

Naples). Photo: Phaidon Press.

c.

Antisthenes, later 3d cent. BC (inscribed herm copy:

Vatican). Photo: Phaidon Press.

d.

Chrysippos, late 3d cent. BC (copy:

British Museum). Photo: Phaidon Press.

3. a.

Epikouros, 270s BC (inscribed herm copy:

Capitoline, Rome). Photo: Phaidon Press.

b.

Metrodoros, 270s BC (inscribed herm copy:

Capitoline, Rome). Photo: Phaidon Press.

c.

Hermarchos, mid-3d cent. BC (copy:

Museum of Art, Budapest). Photo: Phaidon Press.

d.

Menander, early 3d cent. BC (copy: Seminario Patriarcale

di S. Maria della Salute, Venice). Photo: Phaidon Press.

4. a.

Aischines, late 4th cent. BC (copy: Museo

Nazionale, Naples). Photo: Phaidon Press.

b.

Aischines, head of 4a. Photo: Phaidon Press.

c.

Olympiodoros, early 3d cent. BC (inscribed herm copy:

National Museum, Oslo). Photo: Phaidon Press.

d.

Demosthenes, 280 BC (copy: Glyptothek,

Copenhagen). Photo: Phaidon Press.

5. a.

Alexander, 3d cent. BC (Glyptothek,

Copenhagen, cat. 441). Photo: author.

b.

Demetrios Poliorketes, early 3d cent. BC

(herm copy: Naples). Photo: Phaidon Press.

c.

Seleukos Nikator, early 3d cent. BC (bronze copy as bust:

Museo Nazionale, Naples). Photo: Phaidon Press.

d.

Philetairos, ca. 280-260 BC (herm copy: Museo

Nazionale, Naples). Photo: AvP 7. l, pl. 31.

6. a-b.

Attalos I, 230s BC (Pergamon Museum, Berlin).

(a) Photo: AvP 7.1, pl. 31. (b) Photo: DAI, Rome.

The Hellenistic Grave Stelai from Smyrna: Identity and Self-image in the Polis

Paul Zanker

The cities of the Greek East, on the islands and along the Ionian coast, experienced a dramatic economic revival in the second century. BC.[1] They enjoyed royal protection and patronage and, at the same time, profited from the political stability guaranteed by Rome.

Kings and private donors rivaled one another in building stoas, gymnasia, bouleuteria, and theaters. But the more beautiful these cities became, the more their civic life tended to harden into ritual. Living in the shadow of such all-powerful patrons, the Greek cities tried to preserve their identity by looking back to past glory. In the gymnasium the education of youth followed the Attic model of Isokrates. Artists and writers drew inspiration from Classical antecedents.

At the same time, daily life in the private sphere was enriched as never before. Much greater importance was attached to the furnishing of a house with mosaics and paintings, expensive furniture, and silverware. Women wore elegant clothes and precious jewelry. It is as if society were seeking some compensation for the new restrictions on political life.

Although there is an abundance of preserved inscriptions, we learn little of how the populations of such cities really saw themselves. Even the longest texts speak of the same rituals that preoccupied the assembly and the council, especially the generosity of the euergetai and the honors conferred on them and on other deserving citizens. But we hear hardly

[1] This study was promoted by the Kommission zur Erforschung des antiken Städte-wesens/Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Munich. I wish to thank Professor H. A. Shapiro for the translation of this paper. The manuscript was completed and sent to the editor in autumn 1988.

anything of what concerned the individual, or of the shared values that bound individuals together.

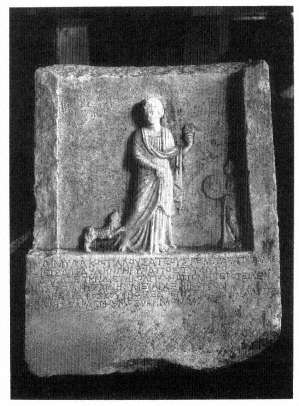

There is, nonetheless, one other rich source of original evidence as yet not really studied from this viewpoint: the countless grave reliefs of the second and first centuries. For ten years now we have had available the admirable corpus of East Greek stelai by E. Pfuhl and H. Möbius.[2] But for our purpose it is difficult to use, since the authors have arranged the reliefs strictly typologically, making the "language" of these reliefs hard to decipher. Only when grouped by provenance and in a roughly chronological sequence do they begin to speak more clearly.

The purpose of grave reliefs had always been to praise the exemplary character of the deceased, either alone or together with relatives still alive, to show their ethical qualities, accomplishments, service, and social status. The essential conformity of their visual language allows us to interpret grave reliefs as evidence from commonly acknowledged values. To some degree the stereotypical pictorial elements of the stelai should be comparable to the topoi of funerary speeches, though regrettably none is preserved from the Hellenistic period.[3] Just as in such eulogies, values are evoked in visual imagery like slogans, and certain patterns remain unchanged over long periods of time. But occasionally, historical currents that provide an interesting picture of a changing mentality seem to leave clearer traces in visual iconography than in literary texts constrained by formula.

Most Hellenistic stelai are not earlier than the second century BC , and they continue into the first. If we try to order the vast body of material roughly by city or region of origin, it is immediately evident that individual cities and areas preferred certain iconographic models and figure types, or even used them exclusively. In order to secure a firm basis for interpretation, we must consider the most important of these local groups in isolation from one another. In the limited space available here I should like to attempt this for the reliefs from Smyrna.

This choice is justified by the fact that the Smyrnaean reliefs constitute one of the most extensive groups, that they have a homogeneous nature, and that they are often of high technical quality. But, as I have intimated above, the results of such a case study must not be turned into broad generalizations, even though stelai sharing many features have been found in a variety of other cities, including Ephesos, Sardis, and

[2] E. Pfuhl and H. Möbius, Die ostgriechischen Grabreliefs , 2 vols. (Mainz, 1977-79) (hereafter cited as P.-M.). See also E. Pfuhl, JDAI 20 (1905): 47ff.; idem, JDAI 22 (1907): 113ff.

[3] D. A. Russell and N. G. Wilson, eds., Menander Rhetor (Oxford, 1981); J. Stoffel, Die Regeln Menanders für die Leichenrede (Meisenheim, 1974).

Kyzikos. In addition, the question of how the self-image tentatively reconstructed here fits into the broader cultural context of Smyrnaean society must, for the time being, remain open.

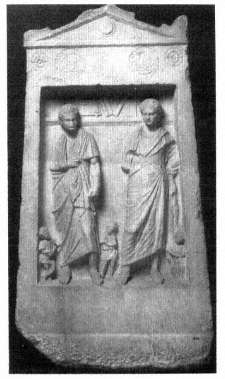

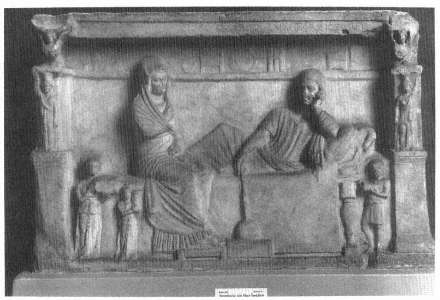

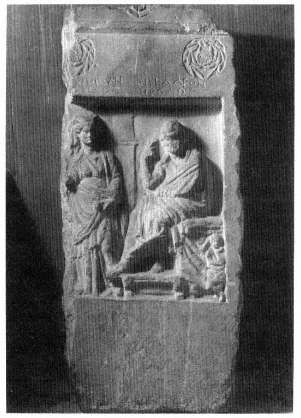

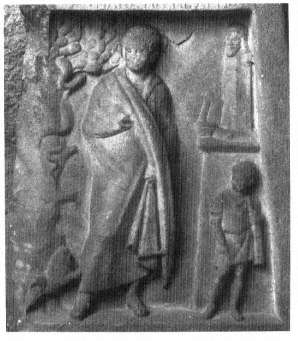

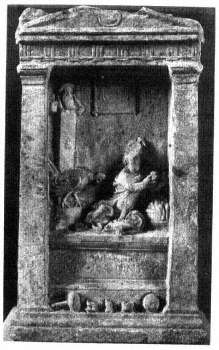

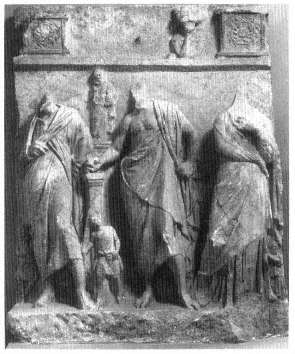

Stelai from Smyrna are relatively easy to recognize, even when the provenance is unknown or questionable. In addition to general conditions of style and iconographic peculiarities, the best criteria are the unique architecture of the stele and a remarkable external characteristic (figs. l, 2). There is an honorific wreath carved above the figures on many stelai containing the inscription  followed by a name and patronymic in the genitive. Since, however, by no means all the figures represented are so designated and the naming of the demos is always omitted in the case of children and of persons whose names are not yet given on the stele as they were still alive, it appears that this is a form of public honor for the dead unique to Smyrna, one awarded to many, though not all, citizens.[4] I cannot pursue here the interesting implications of this and also will not discuss the attribution of individual stelai. The reader may refer to the corpus by Pfuhl and Möbius and form his or her own judgment.

followed by a name and patronymic in the genitive. Since, however, by no means all the figures represented are so designated and the naming of the demos is always omitted in the case of children and of persons whose names are not yet given on the stele as they were still alive, it appears that this is a form of public honor for the dead unique to Smyrna, one awarded to many, though not all, citizens.[4] I cannot pursue here the interesting implications of this and also will not discuss the attribution of individual stelai. The reader may refer to the corpus by Pfuhl and Möbius and form his or her own judgment.

This study is based upon a body of about 140 reliefs, most of which probably belong to the second half of the second century BC .[5] A relative chronological sequence could be worked out on the basis of stylistic analysis but is not essential for the purposes of this paper. There is, however, one fact which can considerably diminish the results of this study: we have no information about the cemeteries or funerary monuments to which these stelai belonged. How did the viewer see these reliefs displayed? Did several stand side by side, as in Attic cemeteries of the Classical period? Does the standard size of the stelai correspond to a standard size of burial precinct, or were these stelai incorporated in tomb monuments of varying types that would have indicated the family's social status? At present we do not have the means to answer these sorts of questions.

[5] Following are the reliefs published in P.-M. which I assign to the "Smyrna Group" of the second and early first century BC : 109, 112, 114, 130 (?), 132, 140, 143, 145, 149, 156, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 167, 168, 169, 170, 250, 251, 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 258, 259, 260, 268, 320, 341, 343, 376, 382, 392, 395, 397, 405, 406, 407, 408, 409, 410, 413, 414, 415, 419, 434, 435, 436, 437, 443, 444, 448, 487, 505 (?), 529, 530, 531, 532, 535, 536, 539, 540, 543, 545, 554, 555, 558, 559, 564, 567, 568, 569, 572, 573, 604, 634, 640, 646, 647, 660, 662, 693, 704, 729, 730, 749, 753, 766, 798, 804, 810, 830, 831, 852, 854, 855, 858, 861, 863, 867, 868, 872, 873, 878, 899, 906, 907, 908, 918, 925, 978, 989, 990, 991 (?), 994, 1030, 1036, 1045, 1052 (?), 1096, 1102, 1430, 1432, 1433, 1436, 1439, 1440, 1450. To these may be added two stelai in Petzl, Inschriften , nos. 23 and 24; and three recently acquired by the Basel Antikenmuseum.

I

On a Classical Attic stele, family members turn to one another, the key figures often joined in a handshake. Posture and gesture become paradigms of the society's ethical norms. The various schemata of standing and sitting and the arrangement of the figures according to their status are all signs that have specific meanings. Both the dead and the living are represented, with few exceptions, with beautiful faces, "beautiful" meaning ideally proportioned and without expression.[6] The only figures that appear mourning are servant girls and slave boys. Attributes and ornament are usually omitted altogether.

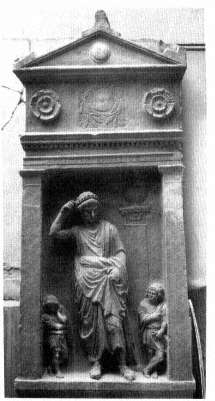

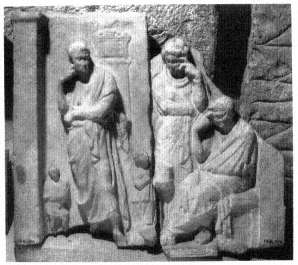

On the Hellenistic grave stelai from Smyrna (and many other cities), by contrast, the figures stand beside each other like statues, looking out at the viewer. There are clear indications that these deliberately imitate or include quotations from public honorific monuments or lavish funerary aediculae. The poses of the figures are precisely those of statues, and occasionally a socle or base is indicated.[7] In addition, the most elaborate of the stelai take the form of small aediculae.[8] In Smyrna, there are also the characteristic wreaths with the inscription

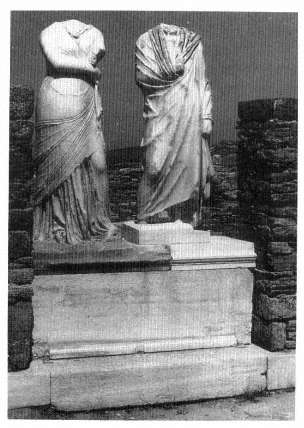

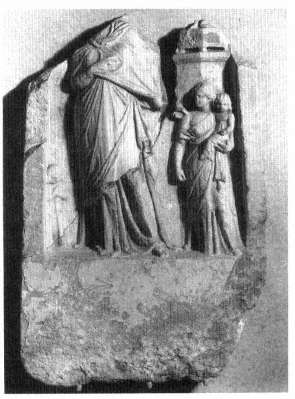

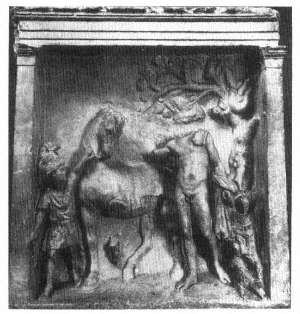

inside. This type of honor from the popular assembly may be considered a kind of substitute for the much sought-after golden wreaths conferred jointly by the boule and the demos. It transforms the tomb into a kind of small public monument. The extensive series of empty socles itself bears eloquent testimony to the important place of honorific statues in the agoras of Hellenistic cities.[9] Such a statue was the quintessential expression of public recognition by one's fellow citizens. Some people set one up in their own homes when they were denied a public one, as is evident from the case of Kleopatra and Dioskourides on Delos (fig. 3).[10] The poses match those on the Smyrna reliefs exactly, and we may conclude that the latter truly reflect the commonly accepted self-image of the free citizen.

inside. This type of honor from the popular assembly may be considered a kind of substitute for the much sought-after golden wreaths conferred jointly by the boule and the demos. It transforms the tomb into a kind of small public monument. The extensive series of empty socles itself bears eloquent testimony to the important place of honorific statues in the agoras of Hellenistic cities.[9] Such a statue was the quintessential expression of public recognition by one's fellow citizens. Some people set one up in their own homes when they were denied a public one, as is evident from the case of Kleopatra and Dioskourides on Delos (fig. 3).[10] The poses match those on the Smyrna reliefs exactly, and we may conclude that the latter truly reflect the commonly accepted self-image of the free citizen.

The pose of the body, the position of arms and head—these are the key elements of the visual language in which these figures are expressed.

[6] See, most recently, B. Schmalz, Griechische Grabreliefs (Darmstadt, 1983), with full bibliographies. There is still no thorough iconographic study of the Classical Attic grave relief.

[7] E.g., P.-M. 1 nos. 532, 831; 2 no. 1475 (from Miletos); more common on the later reliefs.

[8] E.g., P.-M. nos. 405, 415, 539.

[9] E.g., M. Schede, Die Ruinen yon Priene (Berlin, 1964), 48, fig. 57. See also W. Höpfner and E.-L. Schwandner, Haus und Stadt im klassischen Griechenland (Munich, 1986), 86, fig. 68 (Kassope).

[10] R. Lullies and M. Hirmer, Griechische Plastik , 4th ed. (Munich, 1979), pl. 279; Inscriptions de Délos , ed. F. Durrbach et al. (Paris, 1937), no. 1987.

Added to these is a rich assortment of attributes (absent from Classical stelai) which are to be read as symbols of the praiseworthy qualities of the deceased.[11] Among these attributes are male and female servants, usually also rendered in miniature. Again in contrast to the Classical grave relief, the difference in scale vividly emphasizes a difference in social status. Let us now attempt in more detail to decipher the individual elements of the pictorial language.

II

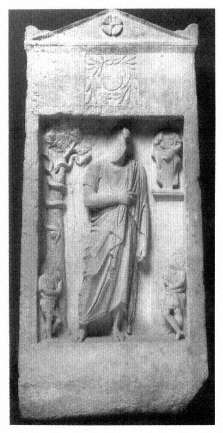

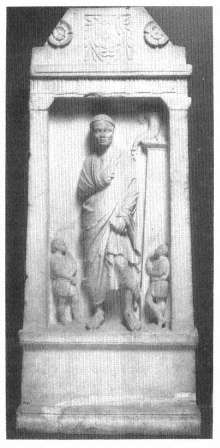

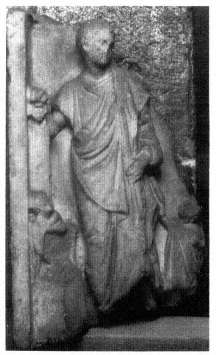

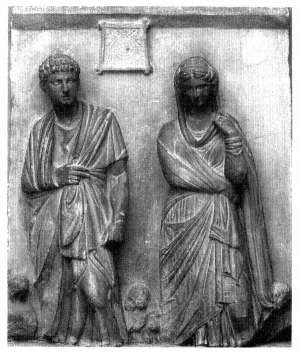

The men on the Smyrna reliefs are often depicted in a manner similar to Classical Athenians of the fourth century (fig. 4). The way the drapery falls or clings and the restrained movement match the honorary statues and grave reliefs of the fourth century, except for one interesting difference: the men now always wear an undergarment beneath the chlamys.[12] This also distinguishes them from the philosophers, who even into the Hellenistic period retain their by now stereotyped "weather-beaten" image. We may surely see in this adherence to traditional standards of conduct a conscious reference to what Greeks in many areas already saw as their past greatness.

The depiction of the standing male figure in the Classical schema, wearing a mantle, permits only a limited number of variations. The most significant of these is the pose of the arms, all the possibilities ultimately aiming at the same effect: a relaxed pose, controlled movement, expressing sophrosyne .[13] The most popular schema of the fourth century, with the right forearm, uncovered, held horizontally across the body and the right hand holding a drapery fold falling from the left shoulder, is now rarely used (fig. 4).[14] Instead, the right arm is usually tightly wrapped in the mantle (fig. 2).[15] That this arrangement is meant above all to show the arms in a position of confinement is confirmed by the equally popular pose of the left arm, and even the left hand, wound in the mantle (fig. 5).[16] This is the most powerful token expressing "restraint" in one's appearances in public. There is indeed a close correspondence here with behavior in real life, as the terracotta statuettes of

[11] E. Pfuhl, JDAI 20 (1905): 47ff., 123ff.

[12] I owe this observation to Professor B. S. Ridgway.

[13] B. Fehr, Bewegungsweisen und Verhaltensideale: Physiognomische Deutungsmöglichkeiten der Bewegungsdarstellung an griechischen Statuen des 5. und 4. Jh. v. Chr . (Bad Bramstedt, 1979).

[14] E.g., P.-M. no. 356.

[15] E.g., P.-M. no. 250.

[16] E.g., P.-M. nos. 158ff.

actors in New Comedy, playing the role of the "earnest young man," attest.[17]

Beyond this general significance, pose and stance were probably also meant to carry a more specific reference to political activity in the boule and ekklesia . This is suggested in particular by several reliefs that depict men in poses very similar to those of fourth- and early third-century statues of Aischines (fig. 2) and Demosthenes.[18] These are surely not, however, meant to invoke famous statues and particular role models,[19] but rather to praise an exemplary standard of conduct in an appearance before the demos. The particular motifs in question are the supporting of the left arm on the hip, the bending of the arms and stiffness of the wrist, and the advancing of the free leg. Demosthenes claims that his rival Aischines would imitate the great orators of the fifth century when speaking, standing still as a statue, with his hand always in his cloak.[20] The statue put up in his honor, preserved in Roman copies, seems to celebrate this public manner as a sign of self-assured competence. The motif of the lowered, linked hands, meanwhile, recalls the statue of Demosthenes. Despite considerable variations—in the statue the fingers are interlaced, while in most reliefs the right hand holds the left wrist—the message is again one of keeping the arms motionless while speaking. In the statue, however, the motif is endowed with a heightened pathos. The sculptor Polyeuktos wanted to show that Demosthenes was full of energy, that it was hard for him to remain still, but that, thanks to his own willpower, he managed to conform to the proper stance. In this way the statue may be seen as a deliberate contrast to that of Aischines.[21] The workshops that produced the grave reliefs used both motifs equally, in order to set varying accents while expressing the same basic, highly prized standards of conduct.

Unlike the women, who are always idealized and youthful, men are occasionally portrayed as individuals, even with indications of advancing

[17] M. Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theater , 2d ed. (Princeton, 1961), 94, fig. 338; idem, Ancient Copies (New York, 1977), fig. 589.

[18] "Aeschines pose": P.-M. nos. 341, 646; "Demosthenes pose": P.-M. nos. 529, 53a, 634, 1102; Petzl, Inschriften , pl. 2, no. 24.

[19] G. Lippold, Die griechische Plastik (Munich, 1950), 314, pl. 108:3; 303, pl. 108:2; M. Bieber, The Sculpture of the Hellenistic Age , ad ed. (New York, 1961), figs. 194-197, 218-221.

[20] Demosthenes 19.251f., 255; 18.129. Cf. Fehr, Bewegungsweisen und Verhaltensideale , 50ff.

[21] My interpretation is at odds with psychological readings like that of T. Dohrn, JDAI 70 (1955): 50-65. The connection suggested here with funerary reliefs cannot be used as an argument for the "tragic" interpretation of the gesture in the statue of Demosthenes. Honorific statues had their own well-established tradition and purpose—to celebrate, not lament.

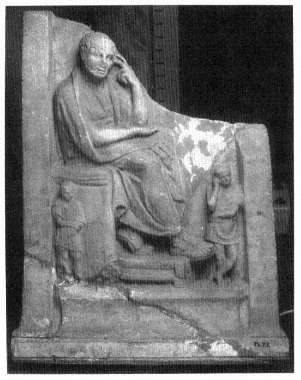

age (figs. 6 and 7, 8 and 9).[22] This is evidently a mark of distinction, as is the seated pose of older men, to which I shall return shortly. On Late Classical Attic grave reliefs one can already trace the way in which advancing age is accompanied by ever more positive associations.

Two stelai with particularly striking portraits have in the background a cornucopia on a pillar (figs. 6 and 7).[23] The single or double cornucopia is several times associated with individuals who held a priestly of-rice.[24] We may thus infer that this symbol, which is no doubt derived from the double cornucopia of the Ptolemies,[25] signifies not just a general prosperity but, more specifically, euergesia . Anyone who could buy himself a priesthood was entitled to be regarded as a benefactor.

At this point we may already suspect that the Smyrna reliefs, despite their evident dependence on more monumental honorific or funerary monuments, reflect not the self-image of a "middle class" (which I think did not exist), but rather a value system acknowledged alike by all free citizens.[26] The men on the stelai thus far considered could be said to present themselves as conservative, adhering fully to traditional behavioral norms of the Classical polis. But other elements and new figure types can change the accent and introduce into the image new standards.

Among attributes, the most important is surely the book roll. We see these often together with writing implements, tablets, and chests, on a pillar or ledge in the background (figs. 2, 10), in the hands of the nearly ubiquitous little slaves,[27] or frequently held by the men themselves (fig. 6).[28] The left hand may even be freed from the mantle for this purpose. The image, which would in later times become endlessly popular, was something new in the second century BC and, as we shall see, is of considerable interest as a symbol of the educated and cultivated man. The book roll indicates education and literary and philosophical interests. Its great popularity reflects the increased importance attached to a man's intellectual training and pursuits in the course of the Hellenistic age.[29]

[22] E.g., P.-M. nos. 156, 159, 270, 831, 855; also a recently acquired relief in the Basel Antikenmuseum, inv. BS 243.

[23] P.-M. nos. 156, 170.

[24] P.-M. nos. 170, 405, 872.

[25] N. Kyrieleis, Bildnisse der Ptolemäer (Berlin, 1975), 164. Cf. Schmalz, Griechische Grabreliefs , 238f.

[26] Even the stelai without relief decoration do not necessarily imply a lower social status, as the wreaths with honors from the demos show. Cf. Petzl, Inschriften , passim.

[27] A good example is P.-M. no. 109.

[28] P.-M. nos. 158ff.

[29] Pfuhl, JDAI 22 (1907): 113ff. On the significance of a literary education in Hellenistic Greece see H. J. Marrou, Histoire de l'éducation dans l'antiquité (Paris, 1965), esp. 152-160, 292-307, 323-336.

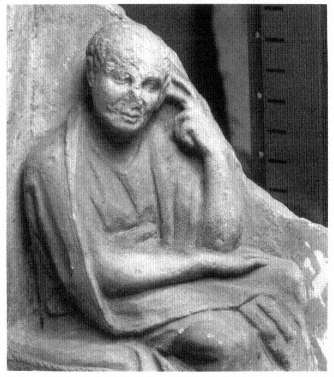

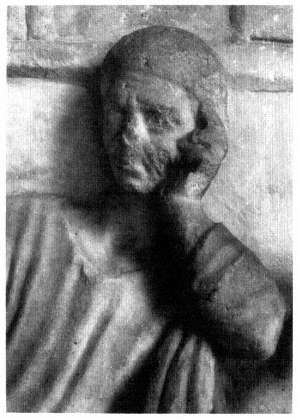

On Classical Attic grave stelai of the fourth century only women are shown seated, and once in a while old men, on account of their infirmity.[30] The Smyrna stelai likewise seem to depict the older men seated, but here the motif makes an unambiguously positive statement (figs. 8 and 9, 11). The man is sometimes shown elevated and on an elaborate piece of furniture; he is a figure of authority. On some stelai he rests his head on one hand, sunk in meditation.[31] This is not, however, a sign of mourning, as Pfuhl and Möbius believe, but rather characterizes him as a thinker. A comparison with third-century statues of philosophers shows that these were indeed the models.[32] The iconographic parallel reveals the tremendous impact of the great thinkers of the past on those in search of a new identity. On one relief, now in Winchester College (fig. 12),[33] a dignified gentleman lectures, while ticking off his arguments on the fingers of his right hand, somewhat like the familiar statue of Chrysippos.[34] His wife is depicted as a priestess of Demeter. Clearly this is a distinguished family that played a major role in public life. Having oneself portrayed as a thinker and reader was evidently considered no less suitable than the traditional Classical type, at least for older men.

The new image as reader or thinker was widespread in the Hellenistic cities of the East. Sometimes the philosophically inclined citizen is shown seated on a proper philosopher's armchair,[35] and even the popular type of the funerary banquet did not preclude the use of this imagery.

There is a particularly fine example from Byzantium of the early first century BC (figs. 10, 13).[36] The deceased, an elderly man with ravaged face, points to the globe, like the muse Urania or one of the Seven Sages on a well-known mosaic in Naples.[37]

The great effort of thinking may occasionally be read in the faces of these "intellectuals," and this in turn has a bearing on the problematical interpretation of Late Hellenistic portraiture. What the modern viewer perceives as exertion or even grief in these portraits is no doubt meant only as a sign of mental activity.[38] Apparently the distinguished citizen

[30] E.g., H. Diepolder, Die attischen Grabeliefs des 5. und 4. Jhs . (Berlin, 1931).

[31] P.-M. nos. 831, 852, 854, 855.

[32] Cf. the so-called Kleanths: G. M. A. Richter, The Portraits of the Greeks , vol. 2 (London, 1965), figs. 1106ff. That the "thinker" pose was already well known and popular in the third century is suggested by, e.g., Plautus Miles 209f. (ed. F. Leo). I owe this reference to Professor Hermann Tränkle.

[33] P.-M. no. 855.

[34] Richter, Portraits 2: 190, fig. 1144.

[35] E.g., P.-M. no. 854.

[36] Well illustrated in P.-M. no. 2034. See also N. Firatli, Les stèles funéraires de Byzance gréco-romaine (Paris, 1964), no. 33, pl. 8; with p. 165 (L. Robert).

[37] Richter, Portraits 1:81, fig. 316.

[38] See G. Hafner, Späthellenistische Bildnisplastik (Berlin, 1954); A. Stewart, Attika (London, 1979), figs. 17ff. and passim; P. Zanker, "Zur Bildnisrepräsentation führender Män-ner in mittelitalischen und campanischen städten zur Zeit der Späten Republik und der julisch-claudischen Kaiser," in Les "bourgeoisies" municipales italiennes aux IIe et Ier siècles av. J.-C . (Naples and Paris, 1983), 252ff.; L. Giuliani, Bildnis und Botschaft (Frankfurt, 1986), 156f.

considered this a quality as worthy of celebration as physical strength, prosperity, good breeding, and other traditional virtues. Indeed, it was only the life of the mind that the Greeks now had to offer their new masters. The steady flow of Roman pupils into the flourishing philosophical schools of Athens and Rhodes attests to the success of the Greeks in promoting this intellectual image.

III

The stelai for youths and young men help confirm what we have observed thus far. While Classical stelai celebrated both athletic prowess and ethical virtue in equal measure in their depictions of the nude youth, on Hellenistic reliefs the youths are almost always clothed, and the only figures shown naked are the little slave boys. In the second century, at Smyrna and elsewhere, there was a distinct reluctance to show a youth or young man nude, and at most a partly bared breast might indicate an ephebe.[39]Paides and ephebes often appear beside a herm of Herakles or Hermes, the standard symbols of the gymnasium and palaistra (fig. 14).[40] The deceased may rest his hand on the herm, to suggest that he enjoyed a proper upbringing and has died young. Just as for adult men, intellectual training is stressed too, in the form of book rolls and writing tablets. Artists did not hesitate to exaggerate this aspect, as in the relief of a young man whose slave opens a container full of book rolls to show the deceased person's great enthusiasm for his studies (fig. 15).[41]

On the many stelai that emphasize in this way the importance of intellectual training, it is equally clear that athletic training was no longer the primary focus of Greek paideia. The ideal of a well-rounded education first formulated by Isokrates seems now to have taken root as a universal attitude.[42]

Victories in athletic or musical competition are not represented as

[39] E.g., P.-M. nos. 140, 646. The motif is more common in other cities, e.g., P.-M. nos. 117 and 150 (Rhodes), 137 (Erythrai).

[40] P.-M. nos. 114ff. Pfuhl's interpretation of this object as a tomb marker is untenable.

[41] P.-M. no. 132.

[42] Marrou, Histoire de l'éducation , 131ff.; G. Mathieu, Les idées politiques d'Isocrate (Paris, 1925; reprinted 1966), 33ff. For the literary testimonia on sophrosyne as the highest virtue of the individual and the state, see Mathieu, Idées politiques , 129. I am indebted to Thomas Gelzer for numerous references in this area.

such, only alluded to in the form of a palm or wreath. On a particularly fine example in Oxford,[43] the deceased crowns himself with a wreath; in the background we see his tomb, an expensive monument bearing the young man's marble urn (fig. 16). Athletic achievement is now less important than the victor's proper ethical stance, which is expressed in the modest pose he assumes.

Boys and youths thus enjoy some of the same types of praise as adult men but assume a distinctly modest appearance. Typical of them are the lowered head and gaze shyly directed at the ground, as on the ephebe on the Oxford relief. This expresses their aidos , a quality to which the Classical period had attached great importance.[44] The Youth from Tralles is a particularly powerful expression of this.[45] In adult men, on the other hand, we may read the vigorous gestures and occasionally upturned head as symbols of energy.[46]

The symbol "Aidos" illustrates how even what appears to be a perfectly natural pose or stance can take on a specific meaning in the pictorial vocabulary of the reliefs.

Young people do not belong to a world of their own. At the tenderest age they are already viewed in their role as future citizens, whether men or women. Even very young gifts are already depicted as little ladies. "Sweet Nikopolis," whose epigram speaks of her "endearing whisper and gentle babbling little mouth," died at age two,[47] but she already has her own servant girl (fig. 17). Naturally, the herms, books, and tablets of the stelai for youths are nowhere to be found on those for girls.

Indeed, even for boys of rather tender years, reference is made to the paideia that they would have enjoyed, had they only lived. On the well-known relief of Amyntes in the Louvre (fig. 18)[48] a shield in the pediment proclaims his arete , while on the wall of the naiskos hangs the framed wreath which would have been his, had he lived to achieve his life's goal. The boy himself, meanwhile, plays and crawls about, like the child he is, trying to defend the fruit he holds from a hungry cock. The

[43] P.-M. no. 149.

[44] Cf. Fehr, Bewegungsweisen und Verhaltensideale , 18 nn. 108, 120.

[45] H. Sichtermann, "Der Knabe yon Tralles," in Antike Plastik , no. 4, ed. W. H. Schuchhardt (Berlin, 1965), pls. 39ff.; H. P. Laubscher, MDAI(I) 16 (1966): 125ff.

[46] P.-M. nos. 159, 161. Rather different is the ephebe in no. 160, whose musical talent is most emphasized by means of the (outside Smyrna) not infrequent element of lyre or kithara.

[47] P.-M. no. 392; cf. nos. 395, 597, 753, 749; W. Peek, Griechische Vers-Inschriften , vol. 1, Grab-Epigramme (Berlin, 1955), no. 1512; idem, Griechische Grabgedichte (Berlin, 1960), no. 228.

[48] P.-M. no. 804. See now H. von Hesberg, "Bildsyntax und Erzählweise in der hellenistichen Flächenkunst," JDAI 103 (1988): 316, fig. 3.

lively scene, however, is presented as if it were a sculptural monument, on a molded socle containing the child's name, his playthings lined up in front. This example shows especially clearly that we cannot expect a unity of time and space on the reliefs. The artists make allusion to a variety of themes and subjects and arrange the elements at hand so artfully that sometimes a seemingly deliberate narrative context results. In looking at the relief of little Amyntes we are apparently meant simultaneously to remember the child as he was in life, at play, to think of the costly monument that his parents set up to his memory, and to be sadly reminded, by the herm, shield, and wreath, that he died so young.

IV

The image of women on the reliefs is almost more stereotypical than that of the men.[49] With few exceptions, sculptors depict all women in the same pose, the so-called pudicitia type (cf. figs. l, 3, 19, 20, 21, 22).[50] This is true even of the few seated women, whose maturity, as for men, is presumably conveyed in this manner. The type enjoyed considerable popularity throughout the Hellenistic world. It must reflect the image of women at this time. But before interpreting the meaning of this statue type, I would like first to consider what it is about women that the reliefs celebrate.

A relatively small variety of attributes and iconographical tokens expresses the female virtues and qualities considered worthy of praise. Instead of a book roll a woman has jewelry or items from her toilette. Large, usually open jewelry boxes, mirrors, alabastra, and combs are displayed on a shelf or pillar in the background, or are held by servant girls. The sun hat and fan also belong here: the woman is a creature of luxury, preening and delighting in little pleasures (cf. figs. 9, 20). We never see her engaged in any activity or holding anything in her hand. The wool basket, a traditional attribute almost indispensable on the stelai (cf. figs. 1, 20), is thus no longer primarily a symbol of the housewife who actually did her housework, but evidently had a broader connotation, as a symbol of feminine virtue and obedience.[51] In fact the reliefs take great pains to make it clear that the deceased was so well off that she never had to lift a finger. Even the most modest stelai include a slave

[49] P.-M. nos. 413ff, 532ff.

[50] Bieber, Ancient Copies , 129ff., figs. 612ff. Cf. A. Linfert, Kunstzentren hellenistischer Zeit (Wiesbaden, 1976), passim, with further references.

[51] Cf. the well-known relief of Monophila from Sardis, with the accompanying epigram: P.-M. no. 141; Peek, Griechische Versinschriften , vol. 1, no. 1881; von Hesberg, "Bildsyntax und Erzählweise," 313f.

girl—usually two, though two is the limit.[52] It is as if to say, the proper household requires a staff of two, and any more would be excessive. Theokritos' poem about the women at the festival of Adonis (15, 24; 68f.) suggests that in this instance too the visual image is an accurate reflection of real life.

Just how closely the pictorial language of the stelai is able to reflect real-life situations is evident on those few reliefs that depict a woman leaving home to appear in public (fig. 23).[53] She moves slowly in her tight, elaborately draped mantle, while servants fuss over her in a flurry of activity. Parasols on the shelf conjure up the setting in our minds,[54] a picture already familiar from the world of Early Hellenistic terracottas.

Two servant girls always assume complementary poses, just like the two slave boys on the stelai for men (figs. 20, 22). While one looks attentively toward her mistress, the other stands immobile, waiting for her next command.[55] Sometimes the servants display their diligence in caring for the children. Nurses enjoyed a higher status and thus are depicted on a larger scale (fig. 23). A garment falling from the shoulder is a typical sign of a nurse's dedication.[56] A servants devotion reflects well on her mistress.

The children in such scenes may be distinguished from the little servants primarily by their liveliness, though otherwise they function just as much as attributes (figs. 21, 23).[57] Bearing children is a woman's duty, though no more than two are ever shown. This too may reflect a sense of propriety, when we recall that exposure of children was expected, especially of girls in prosperous families. Women rarely pay attention to their children, or even notice them. Compared with the images of intimacy between mother and child on Attic grave reliefs,[58] the different iconographic conventions of Hellenistic stelai are especially striking. Here the image of statuesque dignity is clearly more highly prized than the expression of emotion. This is astonishing, in view of the well-known preoccupation of Hellenistic poetry and art with feminine psychology.

This observation suggests a more general characteristic of the iconography of the Smyrna stelai, which is also true of most other Hellenistic

[52] P.-M. nos. 413ff.

[53] P.-M. nos. 382, 506 (from Istanbul), 545.

[54] E.g., P.-M. nos. 437, 539.

[55] E.g., P.-M. no. 414. The same is true of the two slaves regularly accompanying a man; cf. P.-M. nos. 161ff.

[56] P.-M. nos. 382, 443. The garment slipping off occurs often on little servant girls, e.g., no. 435, and on the maid looking down from above on no. 646.

[57] P.-M. nos. 419, 415, 443.

[58] E.g., Diepolder, Die attischen Grabreliefs , pl. 40. Cf. H. Rühfel, Das Kind in der griechischen Kunst (Mainz, 1984), 149ff.

funerary reliefs: the stelai are never concerned with private or personal matters, only with a public presentation embodying universally accepted norms of behavior. The stereotyped forms are the products of conscious constraints. Was it perhaps the fear of being misunderstood or committing a faux pas? Within this seemingly open commercial city on the coast was a society that must have been tightly constricted indeed.

One result of all this is a noticeable difference between the messages conveyed by the funerary epigrams and by the reliefs. Hellenistic epigrams invariably speak of personal misfortune: the loss of both children at once, the early and tragic death of a family member, most of all the grief and suffering of the survivors. The imagery of the epigrams is sometimes downright pathetic and moving. Yet everyone in the reliefs, both the deceased and their survivors, displays the expected, exemplary behavior, without a sign of grief or pain.[59]

A wealthy household is, of course, an accepted standard of success, and the world of women, itself so closely tied to the home, was better suited to expressing this idea than that of the men. One especially elaborate relief conveys the family's prosperity through a carefully rendered aedicula with Ionic columns, a doorpost with lavish curtains, and an unusually large jewelry box (fig. 21).[60] Another relief, reworked in modern times, with the addition of a modern inscription, shows, to the right of the deceased, her own rich tomb, including a statue of a siren playing a threnody on the flutes (fig. 22).[61] Epigrams praise the fine and expensive tomb monument as a token of a husband's love, a means of publicly proclaiming a wife's virtues. The stele with the heavy curtains also displays a kithara, to celebrate the dead woman's musical accomplishment, as do the epigrams.

But why, we may ask, were the pudicitia type and related forms so popular? What connotations were evoked by this type, repeated endlessly on the grave reliefs? Why did the same Hellenistic artists who often stuck quite closely to Late Classical models in rendering the men in honorary statues and grave reliefs so utterly refashion their women?

Hellenistic female statue types invariably emphasize hips and breasts, a departure from Late Classical types (cf. fig. 3). In fact, a corresponding change in proportions is evident in sculpture from the Early Hellenistic

[59] Cf. the selection of epigrams in Peek, Griechische Grabgedichte , 88ff. Among the stelai from Smyrna, P.-M. no. 1102 (= Peek, Griechische Versinschriften 1:701) is a characteristic example. A mother has lost both sons, her husband, and her brother, yet her image does not betray the slightest trace of grief.

[60] P.-M. no. 415.

[61] P.-M. no. 419.

on.[62] The eroticism is also emphasized in the draping of garments. Both the transparency of the drapery and the way it is wrapped tightly about the body produce the same effect, but they also remind us of the precious fabric and exquisite workmanship. Beauty and wealth go hand in hand. An attractive wife was surely considered among a man's most valued possessions, and it is, after all, his fantasies that shape the Hellenistic image of women. Refined and luxurious fabrics help to underline the charms of the female body and, at the same time, show off the family's prosperity.[63] We may at first wonder how the eroticism was reconciled with the well-known strict puritanical standards of conduct for married women. Certainly a glance at other Hellenistic genres, such as the terracotta dancers,[64] leaves little doubt that the erotic connotations of these forms is intentional.

But beauty in the sense of physical attraction and sensuality is but one of several qualities sought in a woman, alongside restraint, decorum, modesty (in Greek, sophrosyne, kosmiotes, aidos, eutaxia, semnotes ).[65] Pose, gesture, and expression must convey the whole range of qualities. The pudicitia type probably has nothing to do with mourning; rather, of all the Late Classical statue types, it best conveys modesty and restraint. Both arms and hands are completely hidden, which almost automatically results in a gentle bend of the head. There is literary evidence that both elements were indeed associated with behavioral norms (Plutarch Praecepta coniugalia 142). But, Plutarch goes on to say, propriety and seriousness in a woman should not lead to harshness and unfriendliness. She should be surrounded by charis , "so that, as Metrodorus [the pupil and friend of Epicurus] says, she does not, with all her virtue, make herself hateful." And indeed, these women in statues and reliefs, though looking so modest, with oblique gaze, not infrequently wear a smile (fig. 24). The paradigm of women on Classical grave stelai seems less constrained than on Hellenistic reliefs. Virtue is now more narrowly defined and is linked more directly to erotic charm. This may reflect the fact that in the second century the institutions of hetairai and pederasty had lost impor-

[62] R. Horn, Stehende weibliche Gewandstatuen in der hellenistischen Plastik, MDAI(R) Ergänzungsheft 2 (1931).

[63] On the famous vestes Coae see RE 11:1475 s.v. "Kos."

[64] E.g., a statuette from Myrina in the Louvre: Encyclopedic photographique de l'art (Paris, 1936) 2:212f.; S. Mollard-Besques, Catalogue raisonné des figurines et reliefs en terre-cuite , vol. 2, Myrina (Paris, 1963), pl. 129 and passim.

[65] Cf. J. Pitcher, Das Lob der Frau im vorchristlichen Grabepigramme der Griechen (Innsbruck, 1979); A.-M. Vérilhac, "L'image de la femme dans les épigrammes funéraires grecs," in La femme dans le monde méditerranéen , vol. 1, Antiquité , edited by A.-M Vérilhec and C. Vial (Paris, 1985), 85-112.

tance—at least in accepted ideology—while marriage and family were most highly valued.

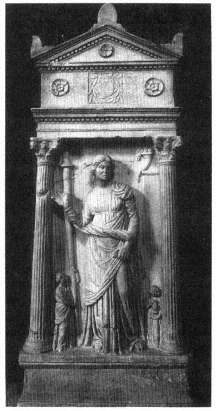

One series of stelai, for priestesses of Demeter, employs a very different, almost grandiose statue type, one that allows much freer movements of the arms (fig. 25).[66] Interestingly, this type also occurs on the Pergamon Altar. Evidently, sculptors turned to the more flamboyant repertoire of Pergamene court art to find an expression of imposing dignity.[67]

This group of Demeter priestesses really deserves a separate investigation. But for our purposes it must suffice to mention one important point, the great variation in quality. Among the twelve or so stelai in this small group is one of the finest and most elaborate of all the stelai from Smyrna (no. 405), along with several whose workmanship is rather primitive. There is an equally wide range of sizes, from no. 407, at only 88 cm in height, to the familiar relief in Berlin which, at 1.56 m, is one of the largest of all. Since all of these represent priestesses of Demeter, we cannot infer from a difference in size a difference in family wealth. Perhaps the contrasts between large and small were mitigated by the setting within the funerary precincts. In any case, as this instance makes clear, we cannot make inferences about the social status of a family from the artistic quality and size of the stele.

Married couples and other members of the family are often depicted together on the stelai, just as in Classical funerary art.[68] But whereas on the fourth-century reliefs the dead and the living turn toward one another, the Hellenistic stelai from Smyrna usually present each figure like an individual statue (figs. 19, 24). Almost all look directly out of the frame, at the viewer, and the scene of dexiosis is rarely encountered.[69] The statuary type thus precludes the possibility of depicting the family bond. One customer's dissatisfaction with the standard type is evident from the tender and moving scene on a stele found reused in the Grin-zinger Cemetery in Vienna (fig. 26).[70]

The sculptor evidently had in his repertoire no way of indicating personal emotion or tenderness, yet this is just what the patron, in direct violation of normal practice, wanted. With the awkward position of the right hand, utterly inappropriate to the figure type, the artist has tried

[66] P.-M. nos. 405-410, 529, 531, 872. Add the new relief in Basel, Antikenmuseum BS 244, and in Izmir, EpigrAnat 3 (1984): 59f, pl. 4a.

[67] Cf. the so-called Tragodia: Bieber, Sculpture , fig. 473; Horn, Gewandstatuen , pl. 18.2.

[68] P.-M. nos. 524, 539, 543, 554ff., 861, 846.

[69] P.-M. nos. 693, 704, 872ff., 1052, 1096f., 1102. Several of these should be dated in the late second or early first century.

[70] P.-M. no. 524f. Despite stylistic similarities, this is not Smyrnean.

to fulfill that wish as best he could. But this is a unique exception, and in general there is hardly any deviation from standard figure types.