The MTA's First Decade

In announcing the "Grand Design" in 1968, MTA leaders had said that Phase I would be entirely completed in ten years—if there were no delays. But delays there were, due to conflicting priorities among MTA, New York City, and suburban officials, between mass transit and highway proponents, between upstate and downstate voters. By 1978, there were significant improvements in the quality of rail and bus service in the 12-county MTA region, but there were important offsetting minuses as well—fares that had risen sharply, and inaction on most of the new lines that had been proposed in 1968.

On the positive side, the deterioration in the region's commuter services had been halted, and significantly reversed on some rail lines. The Staten Island line now had new rolling stock in place of its forty-five-year-old cars, the subway system and the Long Island rail system had more than 600 new cars each, and the New Haven, Hudson, and Harlem lines also sported new commuter cars and other modest improvements. Bus services in the region were stabilized, and in Nassau County the MTA's efforts had reversed the long-term decline in ridership.[101]

On the other hand, in order to meet continuously rising costs, fares had increased substantially since 1968. Although such increases affected rail and bus services throughout the region, the rate of increase was particularly notable on New York City's subway and bus lines, where fares rose from twenty cents to thirty, then thirty-five, and then fifty cents, bringing agonized cries from riders and local officials.

Moreover, while electrification, air conditioned cars and other improvements had some favorable impact on service quality, they did not meet the expectations of commuters, or even of MTA and state leaders. Here the "loss leader" was the Long Island Rail Road. In the late 1960s, Ronan and his aides had distributed to LIRR commuters their plans for the coming decade—including a table showing dramatic reductions of 40 to 50 percent in running time between Long Island stations and Manhattan. But in 1978, the actual timetables were essentially the same as a decade earlier, and some trains even took longer to reach Manhattan.[102] In the summer of 1978, equipment failures

[100] On these developments in Washington, see for example Edward C. Burks, "U.S. to Open Hearings on Rail-Transit Bill," New York Times, July 25, 1977; Ernest Holsendolph, "White House May Let Cities Decide on Transit Funds," New York Times, November 25, 1977; Albert R. Karr, "Mass Transit Gets Short Shrift," Wall Street Journal, December 30, 1977; Message of the President, January 26, 1978; Terence Smith, "Carter Calls for $50 Billion Highway Program With Increased Share for Mass Transit," New York Times, January 27, 1978; Edward C. Burks, "Howard, Roe Say Carter's Transit Bill Does Not Allot Enough Funds for State," New York Times, February 6, 1978; Edward C. Burks, "Carter Signs a Record 4-Year, $51 Billion Bill for Roads and Transit," New York Times, November 8, 1978.

[101] See MTA, Annual Report—1976, pp. 6, 12–13, 17, and MTA, Annual Report—1977 (New York: January 1979), pp. 6–19.

[102] Based on a comparison between the MCTA's original table, distributed in 1966 or 1967, and LIRR timetables in use in July, 1978. A study of LIRR running times, comparing 1903 and 1976, indicated that in general rail travel between Long Island stations had been faster in 1903 than in1976. See Irvine Molotsky, "Audit Disputes L.I.R.R. On-Time Records," New York Times, November 18, 1978.

A typical story circulating among LIRR travelers in the 1970s was the following bit of gallows humor: Seeing a man lying on the LIRR tracks, apparently bent on suicide, a rescuer rushes forward and then notices a loaf of bread in the man's hand. "Why the bread?" he asks. "I was afraid," replies the would-be suicide, "that I might starve to death before the train comes along."

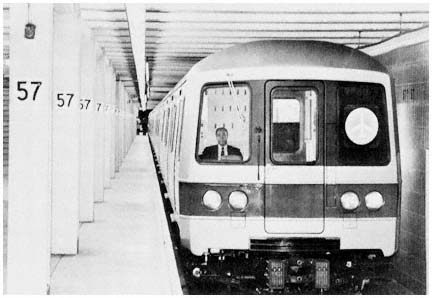

One of MTA's new subway cars operating on the

express line between mid-Manhattan and Kennedy Airport.

Credit: Metropolitan Transportation Authority

and canceled trains had begun to cause political problems for Governor Carey, as they had for his predecessor. Under pressure from the governor—whose spokesman said the railroad was in "hideous shape"—and from commuter groups, the MTA abruptly fired the LIRR president in late July. By general agreement, the LIRR was "in the throes of its worst performance since 1968."[103]

As the energy crisis grew in the late 1970s, the subways, buses and railroad lines of the MTA all experienced significant gains in ridership. But these gains, which continued into the 1980's as gasoline prices remained high, brought as many problems as benefits. MTA revenues were up; but overcrowding became severe, with hundreds of rail commuters standing during long trips from distant suburbs. The added passengers contributed to the increased delays, and at times trains bound for Manhattan were so crowded that they could not pick up passengers at the final inbound stations, leaving

[103] The shape of the railroad, and Governor Carey's political concerns (his opponent was reportedly "relishing the opportunity" to use the LIRR's problems "as a weapon" in the fall campaign) are described in E.J. Dionne, Jr., "Carey Dismisses L.I.R.R. President, Naming a Grumman Aide to the Job," New York Times, July 29, 1978; Robert D. McFadden, "Commuter Groups Offer Advice to New L.I.R.R. Chief," New York Times, July 30, 1978; Irvin Molotsky, "New L.I.R.R. Head Says He Can Be Its Moving Force" New York Times, November 27, 1978.

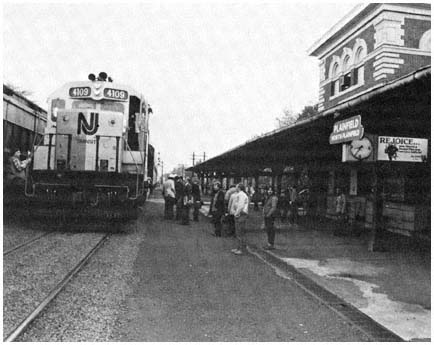

A commuter train operated by the state of New Jersey

picks up passengers at the old Plainfield station on the

former line of the Central Railroad of New Jersey.

Credit: Barbara Reilly, Staff Photographer, New Jersey Transit

weary commuters stranded. The new cars needed to alleviate the crush were not expected to arrive until 1984.[104]

Finally, the program of new construction—the centerpiece of the 1968 plan—had been largely suspended since the early 1970s, a victim of rising costs and inadequate resources. A few segments of the 63rd Street line to Queens, and of the Southeast Queens line, were completed and a few others were under construction a decade later, though they were far behind the original time schedule. Only a small part of the fabled Second Avenue subway had been started, and other projects, such as the new rail line connecting Kennedy Airport with Manhattan and the East Side transportation center in Manhattan, had never moved off the drawing boards. Nor were there prospects for going ahead with most of these projects in the near future. In 1968, the estimated costs for the new transit lines were $1.3 billion; by 1973, the total had risen to more than 2.5 billion. At that point the MTA stopped estimating the cost. In the winter of 1978–1979 the alert pedestrian could still see signs on Fifth Avenue near 63rd Street in Manhattan, proclaiming "the MTA's overall program of adding over 40 miles of new subways," but these

[104] The commuter's fate is aptly described in David A. Andelman, "Rail Commuters Angry but Resigned," New York Times, January 24, 1980.

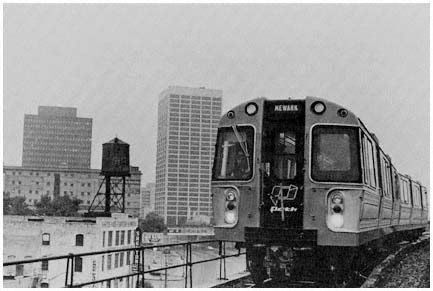

A new PATH train in Newark, from which the

Port Authority's commuter line provides service to

Jersey City, Hoboken, mid-Manhattan, and the World Trade

Center in lower Manhattan.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

were only monuments to past hopes now beyond the authority's means or realistic intention.[105]