Three—

Betrothal Custom and the Arnolfini Sponsalia

If the interpretation of the Arnolfini double portrait as a wedding is inconsistent with the arm and hand gestures in the painting and if the reading of the picture as a depiction of a clandestine marriage is incompatible with the harsh opprobrium and legal disabilities then associated with that practice, these difficulties disappear once the London panel is recognized for what it in fact portrays: the conclusion and ratification of the arrangements for a future marriage by a formal sponsalia, or betrothal ceremony.

The betrothal context of the picture requires an understanding of the relationship between betrothal and marriage in medieval canon law, which is initially somewhat confusing because of changes in the meaning of various words that remain in common use. "Spouse" and "to espouse," both derived from sponsalia, the Latin word for "betrothal," illustrate the problem. "To espouse" once meant "to betroth," rather than "to marry," while "spouse" was formerly synonymous with "bride" or "bridegroom" and designated a person promised in marriage, rather than one who was already married. Prior to the fairly recent establishment of a more restrictive modern usage, these and related words were used concurrently with reference to betrothal as well as marriage. Thus the Oxford English Dictionary gives, as the primary definition of "espouse," "to contract or betroth," and it also documents the use of "espousal" well into the nineteenth century to mean betrothal, rather than marriage.[1] Analogous shifts in meaning are common to corresponding words in many European languages. For example, trauen in German, trouwen in Dutch, sponsare in Italian, and épouser

in French have all come to mean "to marry," whereas formerly they meant "to betroth." Because these changes had begun to manifest themselves well before the fifteenth century, the vocabulary of marriage is sometimes ambiguous in the period covered by this study, especially when taken out of context.

Panofsky touched briefly on these matters, and his remarks, which are not so much incorrect as misleading, provide a convenient point of departure for a more nuanced discussion. According to Panofsky, in Van Eyck's time "the formal procedure of a wedding scarcely differed from that of a betrothal," and both ceremonies "could be called by the same name 'sponsalia' with the only difference that a marriage was called 'sponsalia de praesenti' while a betrothal was called 'sponsalia de futuro.'"[2] Two initial observations are in order. First, although both marriage and betrothal "could be" called sponsalia, they in fact rarely were, particularly in northern Europe after about 1200. Second, despite any superficial similarity between the two, the social and legal implications of the sponsalia de praesenti, which constituted a true sacramental marriage, were entirely different from those of a betrothal, or sponsalia de futuro, which was never more than a promise to marry at some future time.

Because the canon law of the medieval Latin church was a Roman law system, the essential element in the application of marriage law was always intent, as interpreted in light of local custom. Thus the giving of a ring or the joining of the right hands by a priest did not necessarily imply a marriage, since either might be part of some regional betrothal rite. Conversely, the verb desponsare, which in classical usage meant unequivocally "to betroth," was commonly used in medieval Latin to refer to marriage as well. What on the surface appears highly confused was usually clarified by the context. When words of the future tense were employed, as in the statement "I will accept you as my husband," the result could only be a betrothal. But if the consent was couched in the present tense, as in the phrase "I take you as my wife," a binding marriage was contracted.[3] In much the same way we have no difficulty distinguishing a proposal of marriage as a future event from the very different implications of the marriage ceremony itself, just as we would never confuse an engagement ring with a wedding ring.

Put another way, the difference between betrothal and marriage for Van Eyck and his contemporaries was of the same order as the modern distinction between the signing of a purchase agreement and the actual sale of a piece of real estate. To an outsider the two transactions might appear confusingly similar, with the same persons and their representatives concerned with the sale of the same property on two separate occasions. But whereas the second transaction transfers ownership of the property to the buyer and is normally

irrevocable, the purchase agreement, like the betrothal, is no more than a mutual promise to do something in the future. As such it can be broken if the terms agreed upon are not fulfilled, although a buyer who otherwise withdraws unilaterally forfeits the earnest deposited to establish "good faith," as we still say, using the concept of bona fides appropriated from Roman law.

By about 1100, as the ceremonies and legal conventions originally associated with betrothal in late antiquity were being transformed into a new marriage rite, it became necessary to differentiate clearly between a betrothal and what now constituted a marriage. The scholastic distinction between present and future consent grew out of twelfth-century discussions that sought to resolve this problem. In contrast to the fully developed sacramental theory of the thirteenth century, according to which the marriage bond was created instantaneously as the parties gave their consent, Gratian, writing around 1140, held that the bond was not formed until after the consent had been ratified by physical consummation. This more traditional and sequential view of how a marriage was constituted did not ask whether the consent was expressed in future or present terms; once consent was given in either form, the marriage was said to have been "initiated" ("matrimonium initiatum"), with sexual union completing the process to form a valid and legally binding marriage ("matrimonium ratum"). When the marriage law of the Decretum was modernized by the promulgation of the Decretales of Gregory IX in 1234, consummation had been virtually eliminated as a significant factor in constituting a marriage, with the full emphasis now placed on consent in the present tense, which in turn was carefully distinguished from the future consent of betrothal.[4]

Since consent in both present and future was also viewed as a contract, beginning in the twelfth century a related distinction was drawn between betrothal and marriage on the basis of fides as a pledge to abide by a contractual promise. Thus the giving of fides as a promise of future marriage came to be known as fides pactionis, whereas fides as the matrimonial consent was called fides consensus .[5] Both meanings of fides have survived into modern English, albeit in largely archaic form. Since "troth" is the English equivalent of fides, "to betroth" means to give one's fides as an engagement to marry; conversely, if a bride and groom using the traditional wording of the marriage service in the Book of Common Prayer say to one another, "I plight thee my troth," they contract marriage by giving fides to each other as the matrimonial consent.

By the thirteenth century both lawyers and theologians were thus able to differentiate precisely between betrothal and marriage on the basis of these distinctions. The Summa of Raymond of Peñafort, for instance, written in the mid-thirteenth century and thereafter a

standard work on moral theology, rejects the term sponsalia de praesenti as incorrect, indicating that the proper word for marriage is matrimonium . Raymond was in this only following contemporary usage, for by the thirteenth century matrimonium was the common Latin word for marriage, with its binding obligations and sacramental associations, whereas sponsalia, if used without further qualification, was reserved for betrothal, as in Roman law. Significantly, at approximately the same time, De nuptiis ("On Nuptials"), the old rubric for the chapters on marriage in the Roman law as codified by Justinian, was dropped in canon law texts in favor of the dichotomous and more precise De sponsalibus et matrimoniis ("On Betrothals and Marriages") found in the Decretales of Gregory IX and in all the later medieval commentaries on canon law. The preferred expressions of careful writers include sponsalia de futuro for betrothal and matrimonium depraesenti for marriage, as well as the more general, but equally unambiguous, "to contract with words of the future" for the first and "to contract with words of the present" for the second.[6]

Sponsalia de praesenti nonetheless remained in common usage as a popular designation for what long survived as the normative form of marriage in some parts of the Italian peninsula. Where there was continuing political domination by foreigners, as in the south, the marriage rite "in the face of the church" was eventually adopted in one form or another, but throughout much of northern and central Italy the old Roman sponsalia ceremonies were accommodated to the new theological and legal ideas about marriage by a modification less radical than that in transalpine Europe. In this characteristically Italian rite the words of consent were accompanied by the giving of a ring, and hence the ceremony was commonly called subarrhatio anuli . As previously noted, that expression originated in the late Roman betrothal custom—mentioned also by Nicholas I—of presenting the bride with a betrothal ring as an arrha, or pledge that the promise of future marriage would be fulfilled.

By the beginning of the twelfth century this late Roman subarrhatio, or ring-giving ceremony, had been transformed into an Italian marriage rite as the result of a development similar to the concurrent evolution of the church-door marriage rite in northern Europe. And because this Italian marriage ceremony remained much closer in form to earlier betrothal rites, with the words of present consent normally being verified, at least among the upper classes, by a notary at the bride's house, sponsalia de praesenti evidently arose in popular usage as a convenient descriptive term for the ceremony.[7] But there is no question that words of consent in the present tense exchanged in this way constituted a perfectly licit, sacramental marriage as far as ecclesiastical authorities and canon law were concerned,

provided the other conditions requisite for legitimate matrimony were met. Because it is almost certain that members of the Arnolfini and Cenami families residing in Lucca during the fifteenth century would have been married before a notary in such a ceremony—which to us appears more civil than religious—any possible relationship between this archaic form of marriage still common in quattrocento Italy and what is represented in the London double portrait needs to be examined more closely.

The remarkably traditional character of Italian marriage customs is vividly reflected in Marco Antonio Altieri's description of Roman aristocratic marriage at the end of the fifteenth century, which in its main points parallels the short account of Nicholas I written some six centuries earlier. According to Altieri, young women of noble Roman families were so sequestered that few people knew in which houses eligible females lived, obliging parents to engage a go-between, "some venerable priest or good religious," for example, to conduct the initial negotiations. Once a suitable match had been made through the good offices of the intermediary and the financial arrangements for the dowry and prenuptial gift were agreed upon, the betrothal ceremonies were formally concluded in a church, but without the bride. Sometime during the following week, the notary who had drawn up the betrothal instrument came to the house of the bride for the marriage itself. While a relative of the bride held a sword over the couple's heads, the notary verified their consent de praesenti, asking the bride and groom three times in turn whether they wished to take one another for legitimate spouses "according to the laws of the church." After they had answered in the affirmative, the groom placed a ring with his family's coat of arms on the bride's left hand as the notary proclaimed, "What God has joined together let no man put asunder." Following the ring giving, the guests congratulated the bridal couple with best wishes for concordia in their marriage. The church ceremony, deferred for as much as a year or more while the bride continued to live with her parents, was part of a ritual procession of great antiquity that brought the bride to her husband's house. On the day appointed for the nozze, as this rite with its accompanying festivities was called, the bride, wearing her bridal crown and riding a white palfrey (both emblematic of her virginity according to Altieri), was accompanied by the bridal cortège to the entrance of the church. There she was met by the groom, who led her inside for the nuptial liturgy and blessing, followed by a reminder from the priest about the "nights of Tobias." When the service was over, the bride was ceremoniously conducted to her new home.[8]

Italian service books for localities where this ancient form of marriage prevailed have no separate ordo for the marriage rite and contain only the orations and blessing of the old

Roman nuptial liturgy.[9] The evolution of the marriage ceremony proper can nonetheless be traced in notarial sources from Tuscany, if not specifically from Lucca. In the eleventh century the main preoccupation remained the traditio, or physical transfer of the wife from her father's hand to that of her husband. For example, in a Florentine marriage instrument of 1071 that shows strong barbarian influences superimposed on a Roman substratum, the father takes his daughter, described as his "mundualda"—that is, a woman whose mundium, or tutelage, he holds according to Germanic customary law—by the right hand and turns her over ("et sic dedit et tradit eam") to the groom as his legitimate wife. The groom accepts her along with her mundium and with his ring takes her to wife ("et cum anulo suo subbarravit eam"). The remainder of the document concerns the two men's reciprocal gifts of fur cloaks, an exchange that completes the transfer of the bride and her property from the father to the groom. There is no reference whatsoever to words of consent, the willingness of the bride being simply presumed, and the ceremony has no religious framework, save for an opening invocation conventional in legal documents of the period.[10]

Elements of both continuity and change are readily apparent when this eleventh-century marriage is compared with the fifteenth-century marriage rite found in a widely used notary's formulary book "according to Florentine style," which brings us reasonably close to what a marriage must have been like in Lucca during the 1430s. This vernacular order of service for the marriage of a fictive couple named Marietta and Lorenzo carries the title "Matrimonium vulgare" and begins with an exordium read by the notary, not unlike that in a traditional service book such as the Book of Common Prayer. Biblical passages relating to marriage are quoted or summarized, and "holy matrimony," as one of the seven sacraments, is declared so sacred that no one may separate husband and wife for any reason: "What God has joined together let no man put asunder." God and the saints are then invoked that the marriage may be a happy one as the couple grow in love, have the consolation of children along with every other good fortune, and, in the end, save their souls after a long life together. The words of consent take the form of affirmative answers to questions from the notary: "Are you, Marietta, satisfied to consent to Lorenzo as your legitimate spouse and husband and to receive from him the matrimonial ring as a sign of legitimate matrimony, according to the precepts of our holy mother the Roman church?" After a similar question addressed to the groom, the marriage rite ends abruptly, with no words or rubrics specified for the actual giving of the ring. Long and short sample forms for a Latin notarial instrument verifying consent in the present tense follow. The short form, entitled "Matrimony and the Giving of the Ring," epitomizes what was deemed

essential by referring in five different ways to the consent of the spouses in the course of the single sentence that constitutes the entire text: "The lady Marietta and Lorenzo have both together and between themselves with mutual consent contracted legitimate matrimony by words of present tense and by reciprocally giving and receiving the ring."[11]

Thus while the ring ceremony remained a constant element between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, it eventually became the central symbolic action, eclipsing in significance the previously more important traditio ritual. The rite also acquired a solemn religious character, based on the idea that matrimony was a sacrament contracted by the consent of the parties and administered, according to orthodox scholastic opinion, not by the officiating notary or priest, but by the spouses themselves to one another. In some places, notably in Florence, the concluding church ceremony described by Altieri and others was often omitted, but this omission is really not as surprising as some modern historians have thought, for it reflects no more than continuity with a tradition that had prevailed in the time of Nicholas I.[12]

In the Confessionale of Antoninus, a vernacular handbook for priests with limited formal training, these matters are explained in a way that is easy to understand. Antoninus does not use sponsalia de praesenti with reference to marriage, which he calls instead "matrimonio per parole de presenti." He further recognizes that verification of the matrimonial consent by a notary is the normal practice and notes that both sponsalitio (by which he means betrothal in the strict sense) and matrimonio may be contracted at any time of the year. In the case of first marriages, Antoninus regards the nuptial mass and blessing as an obligatory part of the nozze, or ceremonial transfer of the bride to her husband's house, making it sinful for the bride and groom to omit the church ceremony before consummating the marriage. But this rule applies only "where it is the custom to hear such a mass," clearly indicating that in some places, presumably including Antoninus's own diocese of Florence, the religious service was not considered essential. He notes, however, that the nozze may not be celebrated during Advent and Lent or immediately following Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost.[13]

A single-leaf Bolognese miniature circa 1350 (Plate 7), originally illustrating the title "On Betrothals and Marriages" from a manuscript of Johannes Andreae's Novella on the Decretales of Gregory IX, vividly portrays an Italian aristocratic marriage ceremony conducted before a notary.[14] Several figures, apparently members of the household of the bride's family, view the proceedings from a loggia or balcony above what is evidently intended to be an exterior setting, for in practice such a marriage often took place outside the house of the

bride's parents. The outside setting, like the northern church-door rite, was meant to enhance the public character of the ceremony, which the miniaturist has underscored by the presence of the crowd, including musicians, particularly the trumpeters on the right, who are reminiscent of those in the English miniature (see Fig. 18) previously discussed. It is the most solemn moment of the rite that is depicted as the groom gives, and the bride receives, the ring, symbolic of their mutual consent, while the notary embraces the couple by placing a hand on each one's shoulder, apparently just prior to some concluding formula like "What God has joined together let no man put asunder," as in the account of Marco Altieri. The high social rank of the participants is emphasized by the falcon held by one of the groom's attendants and by the presence of three bridesmaids who, like the bride herself, wear crowns signifying their virginity.[15] Purses are worn by the groom and two members of his retinue, presumably to collect the dowry agreed upon at the betrothal. The historiated initial below depicts the rite of the first kiss, yet another ceremony of late Roman sponsalia that had by now become part of the marriage proper.[16]

The notary's embracing gesture is a particularly striking feature of the miniature. Apparently a survival from antiquity, it replicates both the ancient "Concordia" gesture (see Figs. 7 and 8) and the early Christian variant of the same iconography, as exemplified by the Santa Maria Maggiore mosaic (see Fig. 9). The juxtaposition of these ancient works with the Bolognese miniature provides additional evidence that the subarrhatio anuli supplanted the dextrarum iunctio as the normative matrimonial gesture in the Italian peninsula. A comparison of the miniature and the mosaic further suggests that the notary's assumption of the father's officiating role in the Italian rite paralleled the priest's replacement of the father in the northern church-door ceremony. And because this development seems to have occurred in both Italy and northern Europe as the result of the transformation of a traditio ceremony into a sacramental rite, it serves to underscore the equivalency of priest and notary as public witnesses to the couple's matrimonial consent.

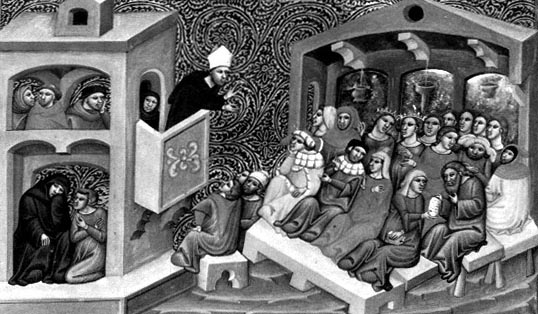

Illustrated manuscripts of Gratian's Decretum permit us to trace these Italian upper-class marriage customs one step further. When the section "On Penance" opens with a miniature depicting a quadragesimale, or cycle of daily Lenten sermons delivered by some prominent preacher (Fig. 23), a pair of these sequestered young women, now safely married by the ring ceremony, is sometimes seen sitting discreetly in the audience, still wearing their virginal bridal crowns as they piously wait for the end of Lent to conclude their nuptials with the celebration of the nozze .

Figure 23.

Quadragesimale miniature. Gratian, Decretum , Italian, fourteenth century. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale,

ms. nouv. acq. lat. 2508, fol. 286r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

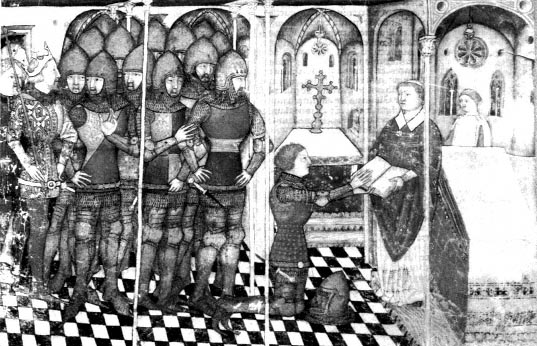

Because images like the marriage miniature of Nicolò da Bologna (Plate 7) appear as normative in canon law manuscripts, it is clearly anachronistic to take the subarrhatio anuli ceremony presided over by a notary for a secular or civil marriage, rather than a religious one, as some modern scholars do.[17] Altieri in fact refers to this domestic rite as a "religiosissimo et venerando sacramento,"[18] and the same ring ceremony is also depicted in Italian works between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries as taking place before a priest, as for example in a fourteenth-century miniature from a manuscript of Gratian's Decretum (Fig. 24), or in a woodcut representing such a marriage before a bishop in the 1514 Giunta edition of the Decretales of Gregory IX (Fig. 25), which illustrates the same title of the canon law as the Bolognese miniature in Plate 7.

An unusual Marriage of the Virgin by Niccolò di Buonaccorso (Plate 8) provides yet another variation of the type. In contrast to the conventional iconography for this subject, which localizes the event within a setting the viewer is meant to associate with the Temple precinct, Buonaccorso has generalized an exterior setting, with a fine Turkish carpet laid out on the pavement before what is evidently the house of the bride's parents, thereby

Figure 24.

Marriage scene. Gratian, Decretum , Italian, fourteenth century. Berlin,

Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, ms. lat. fol. 6, fol. 278r.

Figure 25.

Marriage scene. Decretales of Gregory IX, Venice, 1514, fol. 389v.

creating a domestic Tuscan ambience for the ceremony. His representation of the biblical narrative thus closely resembles the marriage in the Bolognese miniature, the only major difference being the substitution of the high priest for the notary. And because Buonaccorso's picture, as the central panel of a triptych, was originally flanked by panels with the Virgin's Presentation and Coronation, a fourteenth-century viewer would not have found it secular or wanting in religious sentiment.[19]

The medieval notary was by definition a persona publica competent to issue valid public instruments, which he authenticated by his signature and by drawing his distinctive signum, or sign, in the lower left margin of the document, as may be seen in the betrothal instrument in Figure 28. A notary acquired this public authority by license from the pope or the emperor, and by the thirteenth century canonists like Hostiensis and Durantis held that documents drawn up by a notary so commissioned were universally valid, even in lands not subject to papal or imperial jurisdiction. To enhance their status, notaries commonly obtained both imperial and papal authorization for their activities, and instances of this double commissioning of notaries are found even in Flanders by the fourteenth century.[20]

In Italy, not surprisingly, the notary—who often would have been commissioned by the pope himself—had long been held equal to the priest as a public witness to a couple's matrimonial consent. Alexander III, the principal papal architect of the new canon law on marriage that developed in the second half of the twelfth century, casually acknowledged this equivalency when he included among the customary solemnities of marriage the exchange of present consent "in the presence of a priest or of a notary, as is done in some places up to the present time."[21] Centuries later, Florentine synodal legislation of 1517 stipulated that no one should contract sponsalia de praesenti without first calling "his priest or a notary" to verify the consent.[22] At a time when neither ecclesiastical nor civil authorities kept marriage registers, Italian families of means understandably preferred the notary to the priest, for as a legal practitioner, the notary could also redact a notarial instrument of consent in the present tense, thus verifying that the marriage had actually taken place and completing the dossier of marriage documents he had previously prepared.

Gene Brucker's Giovanni and Lusanna, an account of a Florentine mésalliance of the mid-quattrocento, documents the role of the notary from an inverted perspective. When Giovanni della Casa, an upper-class Florentine, sought to continue his liaison with a married woman of artisanal circumstances after her husband's death, the woman's brother insisted on a marriage now that his sister was widowed. Giovanni balked at the presence of a notary at the private ring ceremony, but he did agree to have a friar come from Santa Croce to verify the consent.[23] In this way Giovanni avoided a legal record of the marriage, which

enabled him to claim later, when he wished to marry a woman of his own class, that he had not exchanged words of present consent with Lusanna. This case highlights a major difference between marriage before a notary and marriage before a priest: in fifteenth-century Tuscany the former was inevitably documented by an instrumentum publicum, whereas the latter generally was not.[24]

Although it is thus hypothetically conceivable that a couple from Lucca living in Flanders might have been married during the 1430s in a domestic rite before a notary, a comparison of the Italian ceremony depicted in a work like the miniature of Nicolò da Bologna (see Plate 7) with what is shown in the Arnolfini double portrait highlights the intrinsic differences between the two representations. Most important, the quintessential ring ceremony that characterizes the Italian rite in contemporary representations is missing in the London panel, an absence that would be doubly problematic were the painting intended as a marriage picture, for the giving of a ring was also apparently part of the contemporary marriage ritual in Flanders.[25] Moreover, there is no indication of a notary officiating at the ceremony to verify the couple's consent. Van Eyck himself could not have fulfilled this role: his florid signature alone would not have made up for his lack of credentials as a trained and publicly authorized legal professional, nor could it have constituted the painting itself a legal document, since the date under the signature gives only the year of the ceremony. Furthermore, the woman in the double portrait does not wear the bridal crown traditional in first marriages and familiar in contemporary marriage rites both in Italy before a notary (see Plate 7) and in Flanders before a priest (see Plate 6 and Figs. 20 and 21). And in striking contrast to the emphatically public character of both the Bolognese miniature and Buonaccorso panel—underscored by the numerous guests, the exterior setting, and the musical fanfare of drums and trumpets—the couple in the London painting are shown in a private domestic interior, ostensibly attended only by the two individuals reflected in the mirror. This emphasis on a private domestic event in fact inspired and continues to sustain the view that the ceremony represented by Van Eyck was clandestine.

Despite any apparent resemblance between the words and ceremonies associated with betrothal and marriage, and regardless of all that has been written to the contrary about the London double portrait, according to canon law and theological opinion in the fifteenth century, the effects and obligations consequent to the two forms of consent were entirely different. Whether called matrimonium or sponsalia de praesenti, consent in the present tense constituted the essence of the sacrament of matrimony and created the indissoluble

marriage bond that bound the couple together for life, even if a marriage was never consummated. Betrothal, or sponsalia de futuro, in contrast, was only a contractual promise to marry at some future time. Commentators on canon law generally highlight the difference between the two with definitions taken from Roman law. Sponsalia, they like to say, is "the promise and counterpromise of a future marriage," whereas matrimony "is a joining together of a man and woman, carrying with it a mode of life in which they are inseparable."[26]

The betrothal represented the finalization of the secular aspects of the future marriage, creating a new kinship between the two families and establishing in large measure the future financial and social position of the bride and groom. And whereas matrimonium created a permanent bond that in the eyes of the church could not be broken, sponsalia de futuro, according to canon law, could be dissolved for a variety of reasons: by mutual consent, for example, or if one of the parties married someone else or entered religious life; if a second betrothal was contracted with another person and this was followed by sexual intercourse, thus creating a presumptive marriage that took precedence over the earlier betrothal; if the agreed-upon dowry could not be paid, or if the time limit stipulated in the betrothal agreement expired; if one of the parties contracted leprosy, or was paralyzed, or suffered physical disfigurement by losing a nose, an eye, or an ear; or if one of the parties moved away and could not be found; or if one of the parties committed fornication after the betrothal, including the "spiritual fornication" of heresy or disbelief.[27]

Scholastic writers between about 1200 and 1500 commonly recognize four ways to contract sponsalia . The least formal was a simple reciprocal promise, such as "I will accept you as wife"/"I will accept you as husband." Hostiensis, whose thirteenth-century Summa on the Decretales remained an authoritative text long after Van Eyck's time, terms such a betrothal "nuda et simplex"—that is, "simple and without formalities"—in contrast to three other forms he designates "firmata et duplex," or "confirmed and bipartite," because the promise of future marriage was reinforced to make the contract more secure.

One way to reinforce the promise was by pledging arrha sponsalicia —usually money or jewels—as an earnest that the marriage would take place as agreed. The arrha was forfeited if the party pledging the earnest terminated the engagement, whereas the party receiving the arrha became subject to double, sometimes even quadruple, restitution for breaking the contract. By the fifteenth century, betrothal arrha sometimes took the form of token gifts from the groom to the bride that, given and received, signified the couple's consent to arrangements often made at least in part by other family members. A fifteenth-century

Figure 26.

Flemish betrothal brooch, c. 1430–40. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Flemish jeweled and enameled gold brooch in Vienna (Fig. 26) was almost certainly intended for this purpose. As a figurative allusion to betrothal, it depicts a couple generally disposed as in the London double portrait, with the woman extending her left hand to the man as he reciprocates the gesture with his right hand.

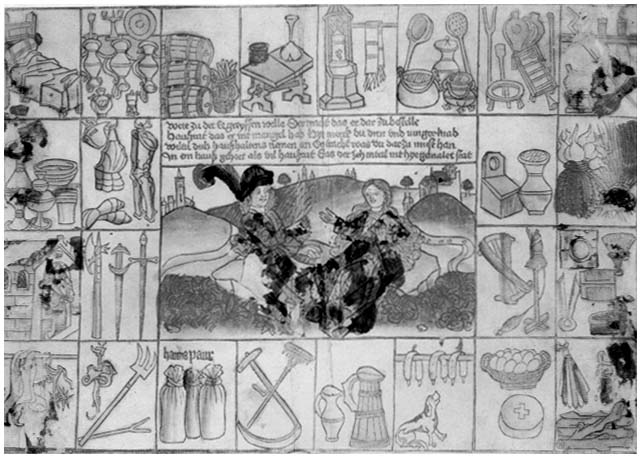

Betrothals were also sometimes confirmed with an engagement ring, as in a Nuremberg woodcut of about 1475 by Hans Paur (Fig. 27). In the center field an elegantly attired couple are seated in an open landscape, as the man offers the woman a ring but with no apparent intent of actually placing it on her finger. The twenty-four surrounding compartments, as specified by the inscription, depict some of the possessions the couple will require to set up

Figure 27.

Hans Paur, German single-leaf betrothal woodcut, c. 1475. Munich, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung.

housekeeping after the marriage, including a bed and trestle table; tankards, candlesticks, and other household plate; cooking utensils and agricultural implements; necessities for personal grooming and hygiene; a horse, saddle, spurs, armor, and weapons for the man; and spinning and other domestic paraphernalia for the woman.[28]

Although the descriptive expression subarrhatio anuli continued to be used for the presentation of a betrothal ring, theologians and canonists insist on the difference between an engagement ring, given with words of future consent, and a wedding ring, bestowed with words of present consent. This same distinction is also commonly expressed iconographically: the groom is represented placing or about to place a wedding ring on the woman's

finger (see Figs. 11 and 12; Plates 7 and 8), whereas the man merely offers a betrothal ring to the woman (see Figs. 27 and 43), who presumably must take it and place it on her own finger.

In the fourth and most formal type of betrothal, the promise of future marriage was fortified by an oath. Hostiensis equates such a betrothal oath with fides, thus using the word with one of its more specific meanings, and in the fifteenth century Antoninus employs the same usage when he says that fides, given unilaterally in a betrothal, refers to an oath.[29]

Fides has yet another meaning in the context of a ceremony for public betrothal in the presence of a priest, which provided yet another way to formalize sponsalia in northern Europe during the later Middle Ages. First documented in the region around Paris in the second half of the thirteenth century,[30] its use in fifteenth-century Flanders is attested by the register of the bishop of Cambrai's court in Brussels (the reader may recall that Catherine Boene was thus publicly betrothed twice in the course of her matrimonial adventures). Seeking to determine whether either party might already be engaged to someone else, the ceremony sometimes began with the priest asking the spouses individually, "Have you made fides with another person?" The betrothal promise, usually specifying that the marriage would take place within forty days, then followed as the couple repeated a set formula after the priest.[31] Although the Ghent rituale of 1576 offers a relatively late example, the form these words take in it is nonetheless typical: "I, N., give you, N., whose hand I hold, my fides that I will take you as legitimate wife."[32] In an earlier order of service from Amiens the priest concludes the ceremony with the words "Et ainsi se fiancez," meaning literally "And thus you have given fides to one another" but conveying as well the modern sense of "And thus you are betrothed."[33] Solemn public betrothal was not, however, thought of as a religious rite, despite the central role played by the priest, since in contrast to any true liturgical ceremony, prayers were normally not used.[34]

It was Marcus van Vaernewyck's 1568 description of the Arnolfini double portrait as the "trauwinghe" of a man and a woman "ghetrauwt" by fides that first associated the picture with the concept of fides .[35] As suggested above in Chapter 1—where the key passage of the description, to retain something of its ambiguity, was translated "an espousal of a man and a woman espoused by fides "—what Van Vaernewyck meant is not entirely clear. For "trauwinghe," like the English "espousal," while still retaining its original meaning of "betrothal," might also refer in the sixteenth century to marriage, just as "ghetrauwt" (like the English "espoused") could mean either "betrothed" or "married."[36] Panofsky's explanation of the central action of the panel was nonetheless based on the assumption that Van

Vaernewyck intended to relate the subject matter of the painting to a marriage, and the confusion was compounded because Panofsky misunderstood the various connotations fides then had. Much discussion of the double portrait has now come to be linked with these mistaken ideas. It is true that fides can mean an oath, and the man in the London picture is indeed portrayed taking an oath, as Panofsky surmised, but there is nothing in medieval canon law about marriage being "concluded by an oath," fides manualis is not referred to in the context of matrimony by any contemporary text, and "fides levata" is no more than an invention of Panofsky's imagination.[37]

The nuanced meanings of fides in the framework of fifteenth-century betrothal and marriage have been further obscured by the failure of Panofsky and others to understand the basic scholastic distinction between the fides of betrothal (fides pactionis ) and the fides of marriage (fides consensus ). A standard exposition of the difference between the two in the Decretales of Gregory IX begins with a straightforward definition: "fides is spoken of in two ways, for the contract and for the consent"; the definition in turn is explained more fully by the glossa ordinaria: "That is to say, one is the fides of espousal in the future tense, and the other, the consent in the present tense."[38] By the thirteenth century fides was used without further qualification for both the betrothal promise and the matrimonial consent, and a contextual reference is usually needed to separate one usage from the other.[39]

In other respects the basic meaning of fides remained unchanged: to "faithfulness," "honesty," and "promise," which are among the primary connotations of the word, Roman law had added the idea of an honest keeping of a promise or the obligations consequent to an agreement—essentially what Augustine meant when he termed fides one of three "goods" of Christian marriage. Fides, in a somewhat broader medieval usage, meant not only a solemn promise to do something, but—by extension—an oath associated with such a promise or agreement. Thus in a feudal context fides can mean either the loyalty of the vassal to the lord or the oath of fealty itself.[40] Similarly, as previously noted, fides in scholastic discussions of betrothal can refer variously to the betrothal promise itself or to an oath sworn to confirm the promise of future marriage, in which case the engagement to marry became firmata et duplex, as Hostiensis and the canon lawyers would say.

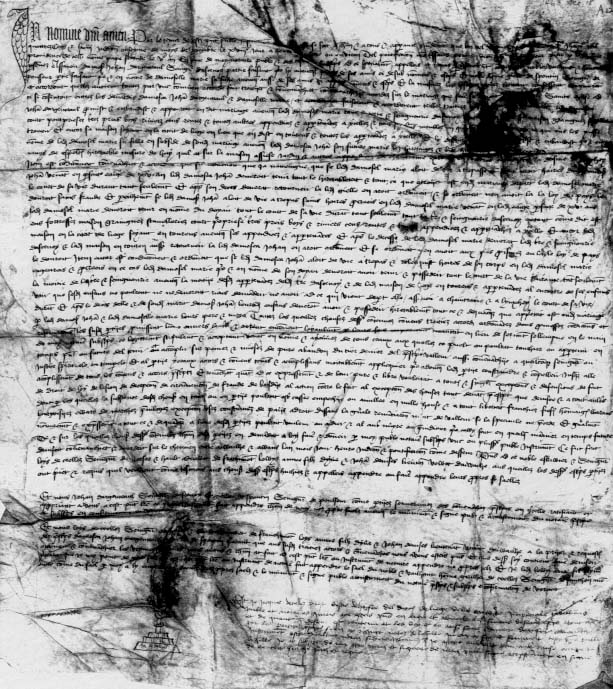

Whether in a particular instance fides was the betrothal promise or an oath fortifying that promise, the question remains, if a painter of the fifteenth century wished to represent a betrothal rather than a marriage, what gestures would have been appropriate to signify the giving of fides? . Actual betrothal instruments survive in substantial numbers from the fifteenth century, but they provide little information about what actually took place at a

Figure 28.

Betrothal contract of Jehan d'Argenteau and Marie de Spontin, 18 December 1463. Washington, D.C., Library of

Congress, Mercy-Argenteau Collection.

sponsalia . A notarial Flemish betrothal contract of 1463 (Fig. 28), for example, is largely concerned with specifying the dowry arrangements for the future marriage of Jehan d'Argenteau, lord of Ascenoy, to Marie de Spontin. What is of interest beyond these legal details is that the document was drawn up by Jacques de Celles, a priest as well as a notary, that the instrument was signed on a road, which is to say in a public place, and that the agreement was made between the groom and the bride's father, Gielle, the lord of Pousseur; Marie herself was not present.[41] Late medieval rituals with an order of service for the newer rite of public betrothal before a priest yield nothing of significance about more traditional ceremonies either, for while they routinely use formulas that equate the giving of fides with the betrothal promise, when an accompanying gesture is indicated by the rubrics, it is invariably the joining of right hands, usually by the priest and in obvious imitation of the marriage rite "in the face of the church."[42] Fortunately other sources, both written and visual, preserve the memory of older betrothal gestures associated with the giving of fides as a promise of future marriage.

Because betrothal ceremonies are less richly documented than marriage rites, what actually happened at a fifteenth-century betrothal is relatively difficult to determine. The detailed account in a consilium of the important Italian jurist Bartholomaeus Caepolla, who was active in the Verona-Padua region in mid-century and died about 1477, is thus of considerable interest. Caepolla's summary begins with a priest standing in a church, before the altar "in the face of the people," and explaining to those present that they have been called together "in this sacred place" to be informed about the dowry arrangements recently concluded between Sempronius and his relatives on the one hand and Titius on the other, according to which Sempronius promises to give his sister Maria in marriage to Titius, who agrees in turn to accept her. The priest asks the two men if this is indeed so, and when they reply in the affirmative, he tells them, "Touch your hands" ("tangatis vobis manum"). After the two men have touched hands, the short ceremony ends, and the guests go to the house of Sempronius for a celebration, in the course of which Maria is introduced for the first time. In the presence of the guests, and holding a cup filled with wine, Titius asks Maria if she is pleased with what her brother and relatives have done. When Maria replies that she is, he offers her the cup, from which she drinks, returning it then to Titius who drinks from the same vessel. Apparently the priest and the ecclesiastical setting serve only to lend greater public authority to the ratification of the contract, for the sponsalia is actually effected by the two men's touching hands, with the woman's consent playing a decidedly

secondary role, when—following a time-honored Lombard practice for confirming contracts, as Caepolla notes—she drinks from the same vessel as her husband-to-be.[43]

Altieri also mentions that the groom and the bride's father confirm the betrothal arrangements in a church by a touching of hands, with the bride again absent. Other Italian sources refer variously to similar gestures in the context of betrothal arrangements as impalmamento and toccamano, and Italian lexicographers note an archaic usage of toccamano to mean the "touching of the bride's hand by the bridegroom."[44] Sometimes in this usage the force of "touching" is rather different from that in modern English, for the romance cognates toccare and toucher can also imply a striking action, as in sounding a bell with a clapper.[45] The gesture stems from a traditional way of ratifying a pact or agreement, a practice to which Accursius, the most important of the medieval glossators on the Roman law, alludes in his apparatus to the Digest when suggesting that the word "pactum" derives from a percussio palmarum, or "striking of palms."[46] And since by the early thirteenth century, when Accursius wrote this gloss, fides pactionis was a conventional Latin expression for the betrothal promise, it would not be surprising if a "striking of palms" constituted one way to confirm the promise of future marriage.

Such a gesture in the context of betrothal was still familiar to Shakespeare and his contemporaries. In the famous scene between Katherine and Henry in Henry V (act 5, scene 2) the English king asks the French princess to literally "strike a bargain" as he concludes his proposal of marriage with: "Give me your answer; i' faith, do; and so clap hands and a bargain: how say you lady?" A similar gesture in the context of betrothal is mentioned in Pierre de Larivey's late sixteenth-century comedy La Constance . The heroine, angry at not having been consulted and threatening to become a nun, explains to a confidante that financial expediency brought about her sudden engagement to a man other than her beloved. On returning home after concluding the betrothal contract with the groom, the young woman's father informed her in the most forthright manner of what had transpired: "Constance," he said, "I've married you off. See to it that you and your mother have the house in order, and get yourself ready, for this evening our Leonard is coming to see you and to touch your hand" ("te viendra veoir et toucher en main").[47] In French usage of the time "toucher en main" was thus clearly an idiomatic expression that referred to the bride-to-be's formal consent, given by a hand-touching gesture, to a betrothal agreement negotiated between her father and future husband.

What makes these instances of betrothal hand touching particularly interesting is that "touching the hand of one another" is how the inventory of 1523/24 describes what is

happening in the Arnolfini double portrait. Since Larivey's language documents hand touching as a betrothal gesture in colloquial French at the end of the sixteenth century, the odds are that the redactor of the inventory entry still understood what the painting represented and by writing "touchantz la main l'ung de l'aultre"—which is the earliest extant interpretation of what the couple are doing—intended to characterize that the panel portrayed a betrothal.

Visual evidence that touching or striking hands was one way to confirm a betrothal agreement during the late Middle Ages is provided by an illumination in the Codex Manesse, where a young couple contract their own betrothal with such a gesture (Plate 9). The early fourteenth-century miniature illustrates a poem of Bernger yon Horheim, in which the poet, about to depart on an expedition to Apulia led by the German emperor Henry IV, takes leave of his beloved by pledging his everlasting love. The short lyric makes no specific mention of betrothal, but that is evidently how the miniaturist read the situation in creating this engaging composition of young lovers exchanging the hand-touching gesture under a stylized tree.[48] Although manuscript painters were not always adept at rendering hands, so that there is considerable ambiguity at times about what an artist intended, such is not the case with the Von Horheim miniature, which is the work of an accomplished artist, the "Maler des Grundstocks," who was the principal illuminator of the Codex Manesse. And since elsewhere in the manuscript the same master has skillfully depicted half a dozen hand-clasping gestures that are unequivocal in meaning, it is reasonable to conclude that what is portrayed in this miniature was meant as a touching or striking of hands, rather than a handfasting or handshaking gesture.[49]

The casual attitude toward the woman's consent in several of these examples is by no means exceptional. Scholastic authors sometimes take up the question of a woman who is too embarrassed or timid to speak up in the course of negotiations concerning her betrothal and eventual marriage. The issue is discussed in a gloss to the Summa of Raymond of Peñafort that provides further information about the gestures appropriate to betrothal. "What if a man," asks the glossator, "laying or fastening his hand on the hand of the woman, says, 'I give you fides that I will accept you to be my wife,' and she says nothing—are sponsalia contracted?" His answer is that the woman's consent may be presumed if she acquiesced or did not disagree when the marriage arrangements were being discussed before the fides was given, "especially," he adds, "if she will have freely given her hand, as required for the receiving of fides ."[50] In discussing the same problem in the fifteenth century, Antoninus hedges at first, thinking that if the woman does not audibly respond to the groom's

words of betrothal, there is no sponsalia, but in the end he repeats almost verbatim the passage just quoted from the Peñafort gloss, although without acknowledging his source, which might well be yet another author.[51] According to Ferraris's Prompta bibliotheca the same gesture as a sign of betrothal consent was still current in the eighteenth century, for the article on sponsalia in this popular clerical encyclopedia notes that a couple "may be presumed to have contracted a betrothal when the stretching out of the hand of one party is accepted without contradiction or resistance by the other party."[52] No reference is made anywhere in these texts to which hands were to be used, suggesting this was of no particular significance when contracting sponsalia .

The evidence presented above establishes a framework for understanding what Van Eyck intended to represent in the Arnolfini double portrait. The giving of fides in the context of sponsalia was synonymous with the betrothal promise, regardless of whether the sponsi themselves acted or others, such as parents or guardians, acted on their behalf. The function of any gesture accompanying the giving of fides was to indicate the consent of both parties to what was being done. And although this could be effected in various ways, including a joining of right hands in imitation of the marriage rite—as in the new form of public betrothal before a priest that had developed by the late thirteenth century—a more traditional gesture, carried out either in private or more publicly before witnesses, involved extending one's arm toward the extended arm of the other person in order to touch or strike hands or to lay one hand against another. The Flemish betrothal brooch in Vienna (see Fig. 26) apparently depicts a gesture of this sort.

Iconographic corroboration for the use of related betrothal gestures is provided by two important Franco-Flemish manuscripts of Boccaccio's Decameron in the French translation prepared by Laurent de Premierfait in 1414 for the duke of Berry. The earlier of the two manuscripts (Pal. lat. 1989 of the Vatican Library) was illuminated by the Cité des Dames Master for John the Fearless of Burgundy shortly before the duke's death in 1419, whence it passed to his son and successor, Philip the Good. The illustrations of the second Boccaccio manuscript, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal ms. 5070, are attributed to the anonymous miniaturists known as the Mansel Master and the Master of Guillebert de Mets working from about 1430 to the 1440s; although the original provenance of the codex is unknown, at an early date it also passed into the famous library of Philip the Good. The two manuscripts, illustrating each of the hundred novelle of Boccaccio's masterpiece with a double vignette, are closely related since the Vatican Palatinus served as the model for the decoration of the Arsenal Decameron, but occasional differences between them indicate the independence of the Arsenal illuminators with respect to the Vatican prototype.[53] These circumstances, cou-

pied with the miniaturists' accommodation of the French version of the Italian text to a Franco-Flemish setting by repeatedly introducing northern forms of betrothal into their reinterpretations of Boccaccio's stories, bring us close in time, place, and subject matter to the Arnolfini double portrait of 1434.

The miniatures of both manuscripts depict three different but closely related gestures for betrothal, but only by inverting Boccaccio's original intentions. To explain briefly, Boccaccio uses sposare loosely with the popular Italian meaning of "betrothal in the present tense," by which he means a true and binding marriage contracted in the characteristic Italian way, by the giving and receiving of a ring. Nozze, in contrast, refers in his usage to the subsequent festivities accompanying the deductio of the bride to her husband's house; religious rites (with the one exception, in novella 2.3, noted below) are not mentioned as part of the nozze celebrations in the Decameron stories. Although Premierfait's French translation faithfully follows the original text, using épouser and noces to render their Italian counterparts, the miniaturists routinely take épouser to mean a betrothal rather than a marriage. The giving of rings, if mentioned, is suppressed in favor of betrothal gestures, and if a noce needs to be illustrated, the artist portrays a conventional northern ecclesiastical wedding ceremony, with a cleric presiding over the joining of right hands, as in the Arsenal Boccaccio illustration of Pampinea's novella (2.3), depicting the pope in the process of formalizing Alessandro's and the "abbot's" earlier clandestine marriage (Fig. 29).[54]

The betrothal gestures in the Arsenal Boccaccio (which closely follow those in the corresponding miniatures in the Vatican manuscript) can be categorized according to an ascending order of formality. The least formal type is illustrated by a miniature (Fig. 30) for Elisa's story of the fifth day (5.3), which concerns a young Roman of illustrious family named Pietro Boccamazza, who falls in love with and wishes to marry a young woman of humble origin named Agnolella. When his family objects to the match as a mésalliance and attempts to intimidate Agnolella's father, the lovers flee the city. Soon they are attacked by brigands, separated, and lost in a vast forest, where each has harrowing adventures before they separately find their way to a castle belonging to the Orsini and are reunited. Although at first reluctant, the lady of the castle, on reflection, agrees to help, and Pietro and Agnolella are "espoused" on the spot. The nozze are arranged and paid for by the lady's husband, after which she accompanies the couple back to Rome and succeeds in restoring Pietro to the good graces of his family.

Although the text envisions an impromptu marriage de praesenti with the lady assisting, the Arsenal miniaturist portrays a betrothal, depicting Pietro and Agnolella outside the castle and without witnesses, executing with their right hands a simple touching gesture

Figure 29.

Boccaccio, Decameron (2.3), c. 1440. Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal,

ms. 5070, fol. 47r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

similar to that in the Manesse miniature (see Plate 9). The circumstances seem to dictate that their betrothal take the form of a simple promise, the nuda et simplex betrothal of Hostiensis and the canonists, and this is evidently what the artist has represented. Because their families were not involved, there surely was no marriage settlement at this point and thus no need or desire on the part of the lovers to formalize the betrothal in a more binding manner. Their love was clearly sufficient, and presumably they expected that the marriage would follow shortly through the good offices of the lady.

A second betrothal gesture illustrates Lauretta's story for the fifth day (5.7), which may be summarized briefly as follows. Messer Amerigo Abate, a Sicilian nobleman, purchased as

Figure 30.

Arsenal Boccaccio (5.3), fol. 191r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

slaves some children captured by Genoese pirates along the Armenian coast, believing them to be Turks. One of them, a boy named Teodoro, he had baptized as Pietro and raised with his own children. Eventually Pietro fell in love with Messer Amerigo's daughter Violante, who, following a short affair, found herself pregnant. When her father, by accident, discovered her giving birth to the child, he ordered the baby killed and Pietro executed, while Violante was given a choice between two methods of suicide. The tale has, of course, a happy resolution. When Pietro's father, Fineo, who is really an Armenian Christian, appears in town on an embassy to the pope, he chances to recognize his son being taken to his execution, saves him from death, and arranges with Messer Amerigo for the marriage of

Figure 31.

Arsenal Boccaccio (5.7), fol. 204r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

the lovers. Pietro resumes his former name, Teodoro, and he and Violante, agreeing to what their fathers have arranged, are "espoused." The nozze follow later, after Violante recovers her strength and Fineo returns from his mission to Rome.

In the "espousal" miniature of the Arsenal manuscript (Fig. 31), reinterpreted as a betrothal in the strict sense, each of the two lovers is accompanied by an individual of the same sex. These figures cannot readily be identified, although the artist apparently intended the man behind Teodoro to represent Fineo, who appears similarly attired at one of the central windows in the first scene of the double miniature. The gesture depicted is one in which Teodoro gently takes Violante's right hand in his left as they touch right hands. The two witnesses lend the episode a note of formality, but as in the case of the betrothal of

Pietro and Agnolella, the reader would scarcely expect elaborate precautions to ensure that the promised marriage would eventually take place. Even if the fathers later agreed on a substantial marriage settlement, as they would be likely to do given their economic circumstances, the couple were clearly lucky to have escaped with their lives. Besides, they already had a child who would immediately be legitimized, according to canon law, as a consequence of the matrimonium of the parents, thus providing an additional reason (from a northern European perspective) for the marriage to take place shortly after the betrothal.

A third miniature of the Arsenal manuscript (Fig. 32) illustrates Pampinea's novella for the tenth day (10.7) with a gesture that parallels what is seen in the Arnolfini double portrait. The heroine of the tale is Lisa, the daughter of Bernardo Puccini, a rich Florentine apothecary living in Palermo. Lisa falls in love with King Pietro of Aragon when she sees him fight in a tournament. Realizing the hopelessness of her situation, she sickens and resolves to die, but not before contriving to inform the king of her love. She asks her parents to summon a minstrel with court connections, Minuccio d'Arezzo; he becomes her confidant and conveys her secret to the king. On the very day he learns of Lisa's infatuation, the king rides to Bernardo's house to visit Lisa and inquire whether she is married. As a result, Lisa makes a speedy recovery. Sometime later, having discussed what could be done for Lisa, the king and queen, escorted by a large retinue of barons and ladies, ride to the garden of Bernardo's house. The girl is summoned, and the king explains that he and the queen wish to reward her by providing a husband. When Lisa accepts and her parents approve, the young man, who is "gentile uomo ma povero" and named Perdicone, is sent for and proceeds to "espouse" the girl, with the king presenting Perdicone with the lordships of Cefalù and Calatabellotta as Lisa's dowry. Subsequently, Lisa's parents and the young couple joyfully celebrate the nozze, while the king for the remainder of his life considers himself Lisa's loyal knight. For Boccaccio, the garden episode is meant to be a public marriage of the sponsalia de praesenti type, celebrated in the presence of the large royal retinue as Perdicone gives Lisa the ring characteristic of the Italian marriage rite, which the king provides at the appropriate moment. The two lordships of "bonissime terre e di gran frutto" that constitute the dowry are not simply promised but really presented, as the circumstances of an actual marriage require.

Laurent de Premierfait's French rendering of this passage closely follows the original Italian,[55] but the Arsenal Boccaccio miniaturist has disregarded the specifics of the text in adapting the scene to a more familiar northern context. Suppressing the ring ceremony entirely, he depicts instead the betrothal of Lisa and Perdicone, who, following a convention

Figure 32.

Arsenal Boccaccio (10.7), fol. 368r. Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

used throughout the manuscript, are represented by their diminutive size as adolescents, with the boy giving fides unilaterally in the form of an oath, thereby formalizing and solemnizing this unusual betrothal arranged and presided over by a king and queen.

As visual documentation for the subject matter of Van Eyck's double portrait, the Boccaccio miniatures conveniently bracket the London panel in time, the Vatican manuscript being a decade and a half earlier and the Arsenal codex slightly later. The miniatures are also uncommonly secure in the contextual information they provide, since as a group they can only be taken to represent various betrothal gestures.[56] Although the Vatican prototypes are similar to the Arsenal betrothal miniatures in all essential respects, there is one minor but notable difference. Uniquely, for there is no other instance of this in either manuscript, the king in the Palatinus miniature illustrating the betrothal of Lisa and Perdicone (Plate 10) does actually hold the ring mentioned in the text, but it serves no evident purpose and is not used, as even the French version of the story requires. The suppression of the ring as a superfluous detail underscores the Arsenal miniaturist's independence of the earlier Parisian model, thereby enhancing the validity of the Arsenal illumination as an authentic representation of gestures accompanying a sworn betrothal in a Netherlandish milieu about the time the London double portrait was painted.

The artists of both manuscripts have also followed a northern European tradition in depicting an oath sworn with the right hand raised. Since this swearing gesture requires the use of the right hand, Perdicone must accomplish with his left hand the characteristic betrothal gesture of touching or taking the extended right hand of his sponsa, who in giving it to him acknowledges her acceptance of the fides as a promise of future marriage.[57] It is in this way, with the same disposition of the hands and arms, that Van Eyck has portrayed the couple in the London double portrait, as their betrothal is fortified with a solemn oath. And just as Van Eyck and the second man reflected in the mirror witness the sponsalia of the Arnolfini, so in the Vatican and Arsenal miniatures the witnesses are the king and queen as well as a third individual, who can be identified on the basis of the pendant scene in both manuscripts as the minstrel Minuccio d'Arezzo, whose services made the happy denouement of the novella possible.

A miniature in a Froissart manuscript illuminated in Bruges circa 1470 provides a further example of the sworn betrothal gestures of the London double portrait: apparently it was meant to depict Richard II's betrothal to Isabelle of France (Fig. 33).[58] This marriage alliance between the kings of England and France was concluded at Paris in March 1396, when Richard's nephew and trusted confidant, the earl of Nottingham, acting as proxy for his uncle, betrothed the young daughter of Charles VI. The following October the two kings

Figure 33.

"Comment l'ordonnance des nopces du roy d'Angleterre et d'Ysabel fille de France se fist." Froissart,

Chroniques , vol. IV, Bruges, c. 1470. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. fr. 2646, fol. 245v.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

met at a ceremonious encampment in Normandy, on which occasion, according to Froissart, Isabelle was delivered over to Richard by her father and taken to Calais. Several days later, on 1 November, just prior to her seventh birthday, the French princess married the English king in St. Nicholas church in Calais with the archbishop of Canterbury presiding.[59]

The Froissart miniaturist has conflated the events of the two-day encampment into a single composite image, whose historical inaccuracy is readily apparent from the artist's depiction of the seven-year-old princess as a mature woman. Froissart does not mention whether the proxy betrothal, described at length in the preceding chapter of the chronicle,

was repeated at the encampment with Richard acting in his own stead. But the possibility that it might have been is suggested by similar circumstances attending the marriage of Philip the Good to his third wife, Isabel of Portugal, in 1429.[60] In that instance, the duke's proxy, Jehan de Roubaix, actually married the Portuguese infanta "par parolle de present" on 25 July in the royal palace in Lisbon. The following January, shortly after the bride's arrival in Sluis, a second, private, rite was held at six in the morning in the infanta's lodgings, when the "words of the present" previously exchanged by the bride and the duke's proxy were ratified in the presence of the bishop of Tournai, who then celebrated mass. In describing the two ceremonies, the same writer notes that the proxy marriage in Lisbon took place in the presence of "a great number of persons of all estates," whereas "only a small number [were] invited" to the Sluis rite.[61] The betrothal scene the miniaturist portrayed—with the French king turning his daughter over to Richard II, who takes the right hand of the princess with his left as he raises his own right hand (seen in profile beneath the left hand of the king of France) to swear the promissory oath—was thus apparently a plausible illustration for a chapter entitled "How the arrangement for the marriage of the king of England and Isabelle of France was made" ("Comment l'ordonnance des nopces . . . se fist").

In a generic sense, the oath sworn by the man in the Arnolfini double portrait is a promissory oath. In such an oath, God is called on to witness that whatever is promised will be carried out. Scholastic commentators further classify oaths in an ascending hierarchy of formality, based on the manner in which the oath was sworn. The oath of the London picture falls into the highest category and is technically termed a solemn, real oath. A real oath, as distinguished from a verbal oath, was effected solely by some appropriate action or gesture and thus required no spoken words, and because the gesture also served to introduce a ceremonial element into the swearing, the oath became, by definition, solemn as well.[62]

Two different gestures were used when swearing a solemn, real oath in the fifteenth century. More common was the iuramentum corporale, or corporal oath, which was sworn by touching the hand to some sacred object—the Gospels, for example, a cross, or the relics of saints—the idea being that from such things "the divine truth shines forth in vestigial form," as one scholastic writer put it.[63] As this was the standard form of the solemn oath in southern Europe, betrothal agreements among upper-class Italian families were customarily confirmed by the bride's father and the groom, each swearing an oath "ad sancti Dei evangelia corporaliter" in the presence of a notary and other witnesses.[64] Since canon law required its use in ecclesiastical courts, the iuramentum corporale sworn on the Gospels was familiar in every part of Europe under the influence of the Latin church.[65] But

Figure 34.

Galahad swearing to join the quest for the Grail. La Geste du Graal , early fifteenth century. Paris,

Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. fr. 343, fol. 7r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

in the north it was more particularly associated with ecclesiastical affairs, although the laity there sometimes swore promissory oaths in this fashion: a miniature (Fig. 34) in an early fifteenth-century manuscript of the Geste du Graal, for example, depicts Galahad swearing on the Gospels, held by a priest, to undertake the quest for the Holy Grail, and a window of about 1500 in the cathedral of Tournai represents a municipal magistrate taking his oath of office the same way, in a church and before a bishop.[66]

A second gesture for the solemn, real oath was peculiar to northern Europe and deemed suitable only for the laity. In this form the oath was sworn by raising the right hand and arm heavenward in imitation of the angel of Apocalypse 10:5–6, who "lifted up his hand to heaven and swore by him that liveth forever and ever."[67] The unusual modern American form of the solemn oath (beginning in the case of inaugural oaths of office with the rubric "Raise your right hand," followed by "I, N., do solemnly swear ...") is a survival of a medieval English usage that combined the tradition of the raised right hand with that of

Figure 35.

Gerard ter Borch, Ratification of the Treaty of Münster , 1648. London, National Gallery.

the corporal oath. A more typically European distinction between the two forms of the solemn oath, coupled with a geographic differentiation in use, is conveniently documented by Ter Borch's Ratification of the Treaty of Münster (Fig. 35), where the Spaniards use the corporal oath (they touch the Gospels) while the Dutch envoys swear by raising the right hand.[68]

Two images of the swearing Apocalypse angel illustrate regional variants in the position of the right hand in the northern form of the solemn oath. In a miniature from the Cloisters Apocalypse (Fig. 36), a fourteenth-century Norman manuscript, all digits of the raised right hand are fully extended, as is also the case in the Vatican and Arsenal Decameron miniatures (see Plate 10 and Fig. 32), the London double portrait, and modern American practice.[69] Presumably that was the original disposition of the hand for an oath of this type, since it is found as early as the Trier Apocalypse of the ninth century. Dürer's Apocalypse of 1498 (Fig. 37) documents the development of a variant form used by the late Middle Ages in

Figure 36.

Angel with the Book . Cloisters Apocalypse, fol. 16r (detail),

Norman, c. 1320. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

The Cloisters Collection (68.174).

Figure 37.

Angel with the Book (detail). Albrecht Dürer, Apocalypse , 1498.

Saint Louis, Missouri, The Saint Louis Art Museum.

some places when swearing an oath—apparently in imitation of the gesture for sacerdotal benediction (see Plate 2) and perhaps with the intent of Trinitarian symbolism—in which the last two fingers are folded down against the palm and the others extended, as in Ter Borch's picture.[70] This alternative gesture of the raised right hand has survived into the twentieth century in Germany and Holland and was used by Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands when she took her inaugural oath in 1980.

When Van Eyck's double portrait is restored to its proper legal and historical context, the meaning of the picture becomes readily apparent. What the artist has depicted is not a clandestine and illegal marriage but rather a solemn sponsalia or betrothal, sworn to by the groom in the presence of two witnesses. The couple touch or lay their hands together in what was then a characteristic betrothal gesture used to express the requisite mutual consent of the couple to the promise of future marriage. When understood in the framework of the contemporary usage of toucher in a betrothal context, the couple's action conforms as closely as one could wish with the inventory description of 1523/24: "touchantz la main l'ung de l'aultre." The man uses his left hand to touch the woman's extended right hand because at the same moment he needs his right arm and hand to swear the solemn, real oath that fortifies the sponsalia promise and requires from him no verbal formula. An air of solemnity pervades the picture because by his gesture in swearing the oath the groom calls God to witness that the marriage will take place as promised. And because, as previously noted, Antoninus indicates that fides was synonymous with a unilateral oath sworn in connection with a sponsalia, even Van Vaernewyck's problematic description of the picture makes sense if what he says is understood to mean "a betrothal [trauwinghe ] of a man and a woman who are betrothed [ghetrauwt ] by fides [i.e. with an oath]."[71]

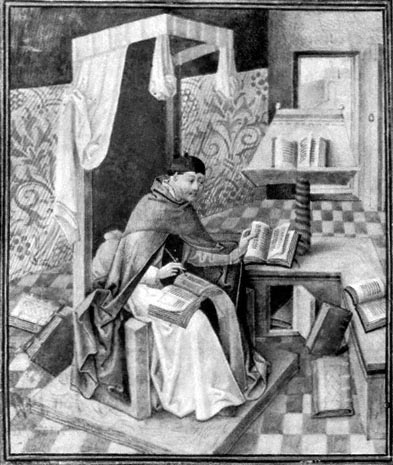

Referred to in the inventory of 1516 without further qualification as a "chambre," the room in the painting cannot be taken for a nuptial chamber, as has often been argued, since there has been as yet no marriage, nor is this interior intended as a bedroom, as critics have frequently presumed.[72] In fact, the hung bed with its canopy as well as the high-backed chair alongside it in the Arnolfini double portrait are prototypical examples of what furniture historians call furniture of estate. Originating in royal courts of the thirteenth century as a means of expressing in visual terms the owner's "degree of estate," hung beds in particular were so important as status symbols that they came to be displayed in reception chambers as ceremonial objects, not intended for ordinary use. Beds are depicted as an indication of high estate in many presentation miniatures of Franco-Flemish manuscripts with a royal or ducal provenance (Plate 11, Fig. 38), and a hung bed of this type is specifically

Figure 38.

The author presenting his Histoire de la conquête de la toison d'or to the duke of Burgundy.

Flemish, c. 1470. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. fr. 331, fol. 1r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

described by Aliénor de Poitiers in her account of Burgundian court ceremonies at the time of the birth of Margaret of Austria's mother in 1456 as "a bed where no one sleeps" ("un lict où nully ne couche").[73]

By the fifteenth century, the wealthy middle class, particularly in England and the Netherlands, imitated noble courts by adopting furniture of estate. They could do this because degree of estate was determined not by rank, which was fixed, but by precedence, which varied with the occasion according to the rank of other persons who were present. The furniture that was exclusively the privilege of a king or a great lord in his court thus became the prerogative of a lesser man in the humbler circumstances of his own house and in the

Figure 39.

Jean Miélot in his study. Le Miroir de la salvation humaine , Flemish, late

fifteenth century. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. fr. 6275, fol. 96v.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

presence of his wife and children. Aliénor de Poitiers also mentions the high-backed chair placed beside the bed—just as in the London panel—"like the great chairs of earlier times," suggesting something of the archaic quality a chair like this had acquired by the mid-fifteenth century. According to these same conventions of status and precedence, authors and scribes are sometimes portrayed in frontispiece miniatures of Flemish manuscripts at work in the seclusion of their studies, sitting in an impressive canopied chair of estate (Fig. 39). And indeed, all the hung beds, cloths of honor, canopied seats, and buffets set with plate that are so commonly seen in early Flemish painting would have been immediately recognized as furnishings of estate by a fifteenth-century viewer.[74]

Figure 40.

Petrus Christus, The Holy Family in a Domestic Interior , c. 1460. Kansas City, Missouri,

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Nelson Fund (56–51).

Figure 41.

Jan van Eyck, The Birth of John the Baptist . Turin-Milan Hours,

c. 1423–25, fol. 93v. Turin, Museo Civico.

As an important indicator of the owner's status, the hung bed, in a middle-class setting, was normally placed in the principal room of the house. Many examples of this practice can be found in early Netherlandish painting, as in the Kansas City Holy Family in a Domestic Interior by Petrus Christus (Fig. 40) and an anonymous Flemish primitive Virgin and Child in Turin (Plate 12);[75] in both cases the hung bed is the principal furnishing in what is clearly the main room, with direct access to the exterior of the house by way of the front entrance (see also Plate 13 and Fig. 38).[76] When Flemish works of the fifteenth century depict hung beds in actual use, the context is usually a birth, as in the Birth of John the Baptist miniature in the Turin-Milan Hours (Fig. 41), or a death, as in the Office of the Dead miniature in the Spinola Hours (Plate 13). On these important social occasions visitors were received in the principal chamber of the house to greet the new mother following her confinement, to assist the dying, or to pay their last respects to the deceased lying in state on a hung bed.

Figure 42.

Claes Jansz. Visscher, Prayer before a Meal , 1609. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

Because, in the words of an authority on furniture of estate, "the canopied bed became inseparably associated with prestige, honour, power, wealth and privilege,"[77] it stands to reason that for rich burghers the hung bed, taken over in emulation of the nobility, continued to have the same social connotations that had led them to adopt it in the first place. This tradition was still very much intact in upper-class Netherlandish households at the beginning of the seventeenth century, as can be seen in an engraving by Claes Jansz. Visscher of 1609 (Fig. 42) that depicts an affluent family at table in a room of patrician proportions with direct access to the exterior that was furnished with an imposing canopied bed (partially visible on the left). Thus as the principal furniture of estate in what is presumably the house of the bride's father, the bed in the London panel provided what must have seemed to a contemporary the most obvious background for a commemorative portrait of the couple's betrothal.

The young woman is apparently at home, while the man appears to be visiting, as suggested by the clogs he has removed on entering. One of the two men whose images are