Introduction:

The Rise of Chinese Travel Writing

"Every traveler has a tale to tell." This ubiquitous European expression not only testifies to the pervasiveness of travel writing in many cultures but also indicates the centrality of the journey in Western narrative. The major genres from the epic to the novel have been constructed around odysseys, pilgrimages, crusades, exiles, explorations, picaresque adventures, Grand Tours, quests, and conquests. A primary guide has been the teleology of the Judeo-Christian tradition, which provided ample myths for the Western traveler to view his journey as ordained by a higher power and potentially redemptive. The exodus of the Israelites to the Promised Land or the progress of saints from the suffering of a profane world to the bliss of Heaven allegorically endowed journeys with the possibility of material reward or salvation of the soul. Tragic wanderings and a profound sense of rootlessness could be interpreted as the consequences of Adam and Eve's egress from paradise or a divine curse. At the same time, Eurocentrism in its many national and historical guises often conditioned Western writers to emphasize the strange "otherness" of the places they visited. Much Western travel writing can be read as an unconscious projection of native values onto other cultures, an exporting of repressed anxieties, or as a fantasy of the exotic. In attempting to come to terms with the difference of foreign places, these texts often reveal themselves to be mirrors of the writer's own desires and illusions.[1]

During the medieval and early Renaissance periods, travel accounts often represented exotic, marginal worlds as fearful zones of demons, infidels, heretics, and natural dangers. Such texts as Wonders of the East presented the "savagery" of distant places with hyperbole and often considerable imagination to satisfy the reader's desire for curiositas .[2]

Given the limited extent of medieval traveling, the representations in these works were mostly accepted as valid even though largely unverified. Despite a general intention to convey what was actually witnessed, such writers usually avoided contradicting the authority of the canonical auctores back home who dominated writing by interpreting individual experience through classical and theological allegories.

It was the travel writing of the Age of Exploration that finally challenged and helped to undermine the medieval worldview. Following the earlier efforts of such traders as Marco Polo in his Description of the World (1298–1299), a host of accounts recorded vastly different cultures and landscapes unexplainable within the established categories of knowledge. Such anthologies as Hakluyt's Principal Navigations (1589) contained many plausible and enthusiastic reports of ocean voyages that resulted in commercial profit.[3] Owing to the increase in trade and colonization, these accounts could now be verified as readers demanded more factual, as opposed to allegorical, truth. Such texts not only encouraged four centuries of adventurous imperialism; they also liberated writers to become individual authors reporting on the unique meaning of their own experience in a variety of narrative forms resistant to traditional classification. As one contemporary critic points out, "Authors exploited the discontinuity between the things in the New World and the words in the ancient books to claim for their works an unprecedented cultural power to represent the new."[4] The "savageness" of these territories revealed to perceptive writers hitherto unrecognized qualities within themselves, while the fashionable consumption of foreign things introduced a new degree of cultural relativism. Romantic Nature, antiquity, and the primitivism of other peoples were often used to frame unflattering assessments of the home culture. Many of the comparisons drawn between these different societies fueled the critique of sociopolitical institutions in Europe, generating support for the revolutionary changes of the past three centuries.[5]

The overlapping of this kind of journalistic reporting with the evolving novel further moved travel writing into the progressive mainstream of Western narrative. The flexible forms of letters, diaries, histories, and romances served both factual and fictional writers as well as those in between. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, popular works based on actual journeys, such as The Travels of Mendes Pinto (1614)[6] and Sterne's A Sentimental Journey (1768), frequently crossed over into fiction so that the writer might put forth liberal opinions about the broader cultural issues of the time. Novels that parodied travel accounts, such as Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726), Bougeant's The Marvellous Voyage of Prince Fan-Férédin (1735), and Vol-

taire's Candide (1759), employed common themes, character types, and plots.[7]

The Enlightenment's optimistic advocacy of individual consciousness was also advanced in a kind of travel writing that used autobiography and biography to explore the self. The affluent increasingly ventured forth on Grand Tours to educate their tastes, enhance their status, and pursue forbidden pleasures. They constituted the core of an everwidening audience that consumed works about people much like themselves encountering distant places. Goethe's Italian Journey (1786), for example, conveyed through letters to friends back home in Weimar not only the writer's perceptive observations along the classical itinerary but also the subjective responses of a sensitive mind discovering itself undergoing change. In Boswell's Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785), the writer filtered many of his experiences of places, history, and society through his observations of the character of his English traveling companion, Dr. Johnson, for whom Scotland was a somewhat exotic location.

Thus, the mainstream of travel writing in the West developed as a means of facilitating the desires of writers and readers for a more liberated, autonomous existence. By defining altered selves in nontraditional accounts of other worlds, it played a role in critical phases of social and political emancipation at home. The twentieth century has witnessed an even greater proliferation of travel writing. Mass tourism has whetted the appetite of readers for more profound observations of places too briefly encountered, while exotic adventures continue to entertain. The paradigm of the journey has been often invoked to signify modern experience. The questioning of classical forms of representation has led to the breakdown of traditional structures of time and space to signify inner peregrinations of the psyche. Figurative language has been conceived of as a migration of meaning, and the act of theorizing as a product of displacement.[8] Texts ranging from the high literary to film and advertising frequently signify reality as a transit through unstable states of being.

By contrast, the travel writing of Imperial China may seem far removed from the historical and intellectual foundations of the West, as remote in its forms and concerns as the land itself. The writers, like their original audience, were mostly degree-holding literati, usually officials and poets as well, whose public lives revolved around climbing up, slipping down, seeking entrée to, or rejecting entirely the ladder of bureaucratic success. In a country without a strong maritime or colonial tradition, their itineraries were primarily internal. Theoretically, they scorned the pursuit of commercial profit and also showed little

interest in foreign countries and non-Chinese ethnic groups. Within a cosmology without a purposeful Creator or strong philosophical interest in the concepts of truth and progress, the dominant Confucian ideology advocated the recovery of a ritualized moral order based on archetypes that were primarily cyclical and spatial. The literary forms of Chinese travel writing evolved out of a matrix where narrative was dominated by the impersonal style of official, historical biography, and subjective, autobiographical impulses were largely subsumed within lyric poetry. Until the latter part of the nineteenth century, journalism was nonexistent and the novel generally regarded as an entertaining diversion.

Chinese travel writing, like its Western counterpart, is voluminous and formally diverse, resisting simple classification. Western readers were first introduced in the late nineteenth century to translations of records by Buddhist monks of their pilgrimages to India and to an ancient chronicle of an imperial tour to the margins of the empire.[9] In the years since then, there has been a tendency to focus on these and similar accounts of political missions to the periphery and beyond.[10] Such texts tend to confirm ideas of Chinese travel writing as being much like our own. They chart difficult quests through alien lands by individuals who objectively report on awesome geographical features and ethnographic oddities.

The mainstream of travel writing, however, was concerned with travel in China itself, and was written by literati for a number of reasons in addition to an impersonal, documentary one. Although scattered antecedents exist in early Chinese literature, it was not until the mid-eighth century, about two-thirds of the way through Chinese literary history, that a set of conventions of representation in prose was codified in the lyric travel account (yu-chi ), enabling writers to articulate fully the autobiographical, aesthetic, intellectual, and moral dimensions of their journeys in first-person narratives; and it was not until the eleventh and twelfth centuries that the travel account and the related travel diary (jih-chi ) actually began to flourish.

In the traditional Chinese classification of literature, travel writing could be found in two principal categories in the Four Libraries (Szupu ) system. Those works that primarily documented geographical features were classified under the geography (ti-li ) subsection of the history (shih ) category.[11] Shorter, more personal pieces such as travel accounts and travel diaries were usually included within the collected works of literati in the belles lettres (chi ) category. These collections were generally published posthumously, and the outstanding ones were continually reprinted through the centuries. From the Sung dynasty on,

as Chinese prose became anthologized and individual pieces canonized as monuments, a number of travel accounts gained widespread prominence. In addition, travel writing was also disseminated through encyclopedias, local gazetteers, and guidebooks.[12]

A further form of transmission, one perhaps unique to Chinese travel writing, was accomplished by engraving texts at the original sites of their inspiration (see fig. 1). By incorporating a text into the environment, the traveler sought to participate enduringly in the totality of the scene. He perpetuated his momentary experience and hoped to gain literary immortality based on a deeply held conviction that through such inscriptions, future readers would come to know and appreciate the writer's authentic self. At the same time, the text altered the scene by shaping the perceptions of later travelers and guiding those who sought to follow in the footsteps of earlier talents. Often, local figures would request or commission such inscriptions by notable visi-

Fig. 1.

Inscriptions on a mountain in Kuei-lin, Kuang-hsi. Photograph by the author.

tors to signify the importance of a place. Certain sites thus became virtual shrines in the literary culture, eliciting further inscriptions through the centuries. The Cave of the Three Travelers (San-yu-tung), first written about by Po Chü-i (772–846) in 819,[*] attracted another set of "Three Travelers" in the Sung, and was further inscribed by Lu Yu (1125–1210) in his A Journey into Shu (1170).[* [ 13]]

For many travel writers, excursions to places that had accumulated a literary tradition were encounters in which Nature was inextricably linked with language and history. Sung Lien's (1310–1381) piece Bell Mountain (1361),[*] for example, is a veritable peregrination through the past, as along his path he notes places associated with events and writers who had preceded him. In such cases, the experience of the inscribed landscape predominated over the encounter with pristine Nature so important to many Western travelers. So pervasive was this mode that several later connoisseurs of the landscape protested against the overinscription of a scene. Yüan Hung-tao (1568–1610) criticized the excessive number of engravings on the Mountain That Gathers the Clouds (Ch'i-yün-shan) as a contamination of the mountain's spirit.[14] Fang Pao's (1668–1749) account of Geese Pond Mountain (1743)[*] praised the purity of this inaccessible spot by noting that no other travelers had yet been able to engrave inscriptions there. But to most writers, the presence of Chinese characters in a scene was not considered a violation of Nature by the artifice of civilization. According to some myths, writing was believed to have originated from the observation of natural processes or animal tracks by ancient sages and was thus regarded as contiguous with the environment. The ordering and enhancing of reality through the artful application of language stood at the heart of the Chinese concept of culture (wen ); it was, indeed, a core function of the ruling class of literati-officials.

In addition to having a purely aesthetic function, this textualizing of the landscape often accompanied social, political, military, and economic development. It was one way a place became significant and was mapped onto an itinerary for other travelers. By applying the patterns of the classical language, writers symbolically claimed unknown or marginal places, transforming their "otherness" and bringing them within the Chinese world order.[15]

Such inscriptions could actually result in the physical alteration of the landscape as it was transformed into a shrine with commemorative

Throughout the Introduction, an asterisk denotes a text that is included in this anthology.

pavilions, gardens, and other features often designed to recreate a writer's original description. Red Cliff in modern Huang-kang, Hu-pei, became such a site of pilgrimage in the centuries following Su Shih's (1037–1101) two influential pieces written in 1082.* Among the structures erected at the site were a sacrificial hall to honor the writer and a pavilion to house copies of his original calligraphy. Recently, a statue of Su Shih himself was erected, and in 1982 an academic conference was held at the site to discuss his travel writings. Similarly, although the original location of Wang Hsi-chih's (ca. 303-ca. 361) Orchid Pavilion, which he recorded in 353,* was in the intervening centuries forgotten, it was subsequently recreated outside modern Shao-hsing, Chechiang, with a winding stream similar to the one Wang mentioned.[16] Of course, it was not necessary literally to engrave one's text at the site: producing a widely read account was often sufficient to gain the writer inclusion in the genius loci .

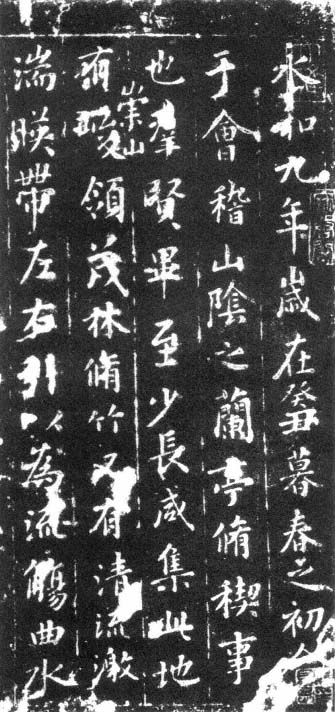

Engraved inscriptions were not only read by later travelers to the site, but were also widely reproduced in rubbings sold as souvenirs. Later calligraphers, moreover, reinterpreted earlier versions or rewrote them in their own styles, further disseminating these texts.[17] A number of texts gained enormous prestige through rubbings of engravings of the original calligraphed versions. Wang Hsi-chih's Preface to Collected Poems from the Orchid Pavilion (353)* was engraved many times and became the most influential model of the "running mode" of calligraphy, even though the original had long since disappeared (fig. 2). Likewise, one of Su Shih's handwritten versions of his first piece about Red Cliff* survived and has been revered through the centuries as a masterpiece;[18] it, too, was widely reproduced in numerous engravings and reinterpretations (fig. 3). Both these texts also established enduring painting traditions as artists over the centuries created conventional formats based on the scenes described. Scholars in a boat beneath a cliff inevitably signified journeying to Red Cliff; poets seated along a winding stream with floating winecups was instantly recognized as the gathering at the Orchid Pavilion. These two sister arts were also combined, with the texts of travel accounts being appended to images depicting the scene. The Ming painter Shen Chou (1427–1509), for instance, added such a text to the end of his 1499 handscroll of Chang's Cave (Changkung-tung; fig. 45); and the Ch'ing artist Chin Nung (1687–1773) produced an album of twelve leaves in 1736 in which he illustrated scenes from famous travel accounts and inscribed the texts as colophons (figs. 20, 23). Lastly, both images and texts appeared in the decorative arts, applied to a wide range of objects; some of these motifs continue to be employed by Chinese artisans today.[19]

Fig. 2.

Wang Hsi-chih (ca. 303–ca. 361), Preface to Collected Poems

from the Orchid Pavilion (detail, original 353). From a rubbing

of the Ting-wu series of engravings reproduced in Shu-tao

ch'üan-chi , vol. 4: Eastern Chin (Taipei, 1976).

Compared to Western travel narratives, however, travel writing was more marginal within the Chinese literary canon. The journey was less central mythically to Chinese cultural experience, which is noted for lacking a definitive epic account like the Odyssey , nor did it play a major role in the development of the Chinese novel. Monumental examples of the explorer's narrative, such as The Travel Diaries of Hsü Hsia-k'o (1613–1639),* stand out in the literary landscape like solitary peaks. Some of the most heroic journeys, including Cheng Ho's (1371–1435) seven voyages to South Asia and Africa in 1403–1431, yielded only secret official reports, which subsequently disappeared, and no literary accounts.[20] Despite the inclusion of a number of travel accounts in the early prose anthology Finest Flowering of the Preserve of Letters (Wen-yüan ying-hua , 987), in this and most other influential collections travel writing was generically subdivided and subordinated to other categories.[21] When included in the collected works of individuals, travel writing formed but a minute portion; genres such as memorials to the throne, epitaphs, biographies, essays, letters, and prefaces were the ones usually looked to for serious stylistic and thematic statements. The earliest extant anthology exclusively devoted to travel accounts is a handwritten manuscript from the fourteenth century, which contains the table of contents from an earlier collection dated 1243; at least by then, apparently, travel writing had begun to be regarded, by some, as an independent genre.[22] Although scattered critics during the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties took note of the travel account, as late as the first half of this century the term yu-chi still had not appeared in the classical dictionaries Tz'u-yüan (1915) and Tz'u-hai (1938). It remained for modern Chinese anthologizers to argue for travel literature as a major prose genre in its own right and to reintroduce it to contemporary readers.[23]

The traditional division of Chinese travel writing into history and belles lettres reflects a distinction between public, impersonal forms and more private modes that included the representation of the subjective self. This duality was further reinforced by the presence of two principle discourses in classical Chinese, which were combined in varying

Fig. 3.

Su Shih (1037–1101), Red Cliff I (detail from Su Shih's handwritten version). National Palace Museum, Taipei. The missing title and first four lines on the

right were added later by the Ming artist Wen Cheng-ming (1470–1559).

proportions within most texts. At one pole was the objective, moralizing perspective of historiography; at the other, a mode of expressive and aesthetic responses to the landscape derived from poetic genres that could be termed "lyrical."

Historiography provided the earliest forms of narrative in China and continued to dominate most prose writing until the modern period.[24] Its primary function was to document human behavior in society within a framework of Confucian moral judgment, as a guide to readers involved in statecraft. The historian created an omniscient, third-person voice and a terse, unembellished style of prose. He typically defined the self from an exterior perspective, against a background of exemplary types enacting well-defined roles. Time in these accounts was conventionally represented by means of the recurrent cycles of Chinese chronology; space was charted along an axis emanating from the power center of the court to the margins of the provinces. As a writer, the historian was primarily a processor of information that he collected, evaluated, edited, and retold. He regarded himself as engaging in a self-effacing act of documentation, which allowed him effectively to transmit the meaning of events with the proper combination of factuality and literary embellishment. There was from the outset a

close connection between historiographical discourse and state power, in that the office of the Grand Historian (T'ai-shih ) was originally hereditary. The court's desire to dominate the writing of history was so intense that at times the private compilation of history was decreed to be illegal, with such acts, when discovered, even resulting in imprisonment. Thus, when a travel writer adopted the narrative persona of the historian, he was appropriating a potent form of literary authority. At the same time, because the conventions of historiography governed content, they tended to direct the writer's concerns toward the public values and issues of official, court-centered culture.

Historiographical conventions dominate almost exclusively in the few extant examples of early travel writing; they also constitute the primary discourse in works informational in nature, such as guidebooks, records of cities, and accounts of journeys to foreign lands. It was not until the period of disunity during the Six Dynasties that a complementary, lyrical discourse began to appear in prose, expressing what Yu-kung Kao has defined as the quintessential ideals of "selfcontainment" and "self-contentment" in Nature.[25] The rise of lyric shih poetry, the rejection of public life by many writers, and the search for alternate spheres of being such as transcendence in Nature supported

new, personal forms of literature apart from the political focus of the court. In contrast to historiography's paradigms of totality, Chinese lyricism sought to represent an alternate vision. The lyric poet, operating from a more interior ground of being than the historian, often captured his momentary experiences of self-realization in descriptions of landscapes. In an autobiographical act, he signified an identification of his inner feelings (ch'ing ) with the sensual qualities of scenes (ching ), using highly imagistic language that often obscured the distinction between observer and object. Similarly, he explored a more subjective sense of time by coordinating shifting perspectives to evoke a vision of the universal Tao as a process of endless transformation.

Lyric travel writing ultimately emerged as the most literary means of representing a journey. Its essential character was defined by the incorporation of individual poetic vision within a narrative framework derived from historiographical discourse. Thus lyric travel writers, whose works are the major focus of this anthology, wore the dual mask of historian and poet (in fact, they were often writers of biographies and poetry as well). They created sublime, self-centered worlds—marginal places universalized—as substitutes for the politicized dynastic scene with its unstable and unpredictable power center. Indeed, the lyric travel account grew out of the tension between the public and private aspects of the self experienced by exiled officials, such as Yüan Chieh (719–772) and Liu Tsung-yüan (773–819) of the T'ang. These men's achievement of one of the few genuinely autobiographical forms in Chinese prose was the watershed between a long period of development, when travel writing was dominated almost exclusively by historiographical concerns, and the later, mature phase of travel writing, which sought to inscribe the landscape with the perceptions of the self.

Early Chinese Travel Writing

Prior to the travel accounts and travel diaries of the T'ang and Sung, relatively few prose texts survive that are concerned with the representation of a journey. The Book of Documents (Shu ching , early-late Chou dynasty) contains mythicized descriptions of the ritualized tours of the ancient sage-king Shun:

In the second month of the year, he [Shun] made a tour of inspection to the east as far as Tai-tsung [i.e., T'ai-shan, the Supreme Mountain], where he made a burnt offering to Heaven and sacrificed to the mountains and

rivers according to their importance [fig. 8]. He received the eastern nobles in an audience and put their calendar in order, standardized the musical pitches and the measures of length and volume as well as the five kinds of rituals. He was presented with the five tokens of rank, three kinds of silk, two living animals and one dead one; he returned the five tokens of rank to the nobles. After finishing his tour, he returned to his capital. In the fifth month, he made a tour of inspection to the south as far as the Southern Sacred Mount, to which he sacrificed in the same manner as at Tai-tsung. Likewise, in the eighth month, he made a western tour of inspection as far as the Western Sacred Mount. In the eleventh month, he made a tour of inspection to the north as far as the Northern Sacred Mount, where he sacrificed as he had in the west. Upon his return to the capital, he went to the Temple of the Ancestor and offered up an ox.[26]

This passage indicates the earliest reasons for writing about travel: to document heroic achievements in ordering the political, spiritual, and material dimensions of the world and to provide a guide for later rulers.

These public themes are paramount in the earliest extant travel narrative of any length, The Chronicle of Mu, Son-of-Heaven (Mu T'ientzu chuan ), whose earliest strata have been dated around 400 B.C.[27] It tersely chronicles an imperial tour by Emperor Mu of the Chou (r. 1023–983 B.C.) through his realm—an example of what David Hawkes has called "itineraria," that is, representations of ritual progresses, as well as of imaginary or supernatural quests.[28] The ritual progress in particular is a circuit by a powerful figure such as a king or wizard through the zones of a symmetrical cosmos. Each zone is presided over by a god or political figure who confirms the traveler's authority or acknowledges submission in ritualized encounters (fig. 4). The traveler ultimately returns to the power center of the capital having thus demonstrated his control of totality.

The Chronicle of Mu reads like a record of the public activities of the emperor by a court historian:

On the day chia-wu , the Son-of-Heaven journeyed west. He crossed the hills of the Yü Pass.

On chi-hai , he arrived at the plains of Yen-chü and Yu-chih.

On hsin-ch'ou , the Son-of-Heaven journeyed north to the P'eng people. They are the descendants of Ho-tsung, Ancestor of the Yellow River. Duke Shu of P'eng met the Son-of-Heaven at Chih-chih. He presented ten leopard skins and twenty-six fine horses. The Son-of-Heaven commanded Ching-li to accept them.[29]

Fig. 4.

Emperor Mu Meets the Queen Mother of the West (rubbing from a Han

dynasty engraving). From Ku Shih, Mu T'ien-tzu chuan hsicheng chiang-

shu (rpt. Taipei, 1976). This fragment depicts the emperor riding in his

chariot with his attendants in the foreground.

The text constitutes the traveler as a man who completely dominates his environment. He demonstrates his control by journeying to distant locations by horseback and chariot, engaging in political and religious rituals, hunting, banqueting, accumulating and distributing tribute, judging his subjects, and receiving benefits in encounters with spiritual beings. Emperor Mu is largely represented as an impersonal function of the rituals of statecraft; there is little explanation in the text of his inner motivations. We do get a brief personal view when the emperor voices doubts about the moral correctness of his traveling and questions whether he will be judged by history as a profligate for leaving the capital. Here, the text seems to be answering the criticism of Emperor Mu in the Confucian classic The Tso Commentary to the Spring and Autumn Annals (Ch'un-ch'iu Tso chuan )—that Emperor Mu "wished to indulge himself" by traveling throughout his kingdom.[30]The Tso Commentary adopted a negative attitude toward this behavior and praised the officials who remonstrated with him, persuading him (supposedly) to remain at home and die a natural death in his palace. This is the Confucian view. Unfortunately, the beginning of The Chronicle of Mu is missing, and the work provides no further statement of the emperor's motivations.

Nevertheless, Emperor Mu's concern with the issue of travel bespeaks a primal principle of Chinese political culture, what could be called "the politics of centrality," in which power is believed to emanate from a fixed center and threatens to become dissipated when the center is destabilized and loses its ritualized authority. For the ruler to abandon the capital and travel for pleasure rather than necessity was a serious moral issue, for it meant that he risked losing dominance over the very margins he was visiting. Differing from the negative judgment of The Tso Commentary, The Chronicle of Mu quickly resolves this problem when the emperor is assured by a flattering knight that history will not criticize his desire to travel as long as he maintains the world in a proper state of order, which the ritualized encounters on his journey demonstrate.[31]

The Chronicle of Mu records an early act of inscribing the landscape when it states that after visiting the Queen Mother of the West and banqueting at the Jade Pond (fig. 4), "The Son-of-Heaven rode up to the Hsi Mountains where he engraved a record of his journey into the rock and planted a huai -tree, naming the place 'Mountain of the Queen Mother of the West.'"[32] In the ritual tours of emperors documented in the dynastic histories, such inscriptions enunciated praise of sagely rule, projecting the ruler's extension of his authority and signifying his possession of the world.[33] Their ideological function was to project

domination, while the required response of the reader was awe and submission.

The other major example of travel writing that has survived from early antiquity, Guideways through Mountains and Seas (Shan-hai ching , ca. 320 B.C.–A.D. 200), is also an anonymous work and is composed of several strata. Some parts of it appear to have been a guidebook for travelers through known territory; other parts seem to be a description of mythical lands unlikely to be visited. Both types of landscape are filled with fantastic beings.[34] The itineraries through known mountains in each direction note natural features, local objects of value, and the resident gods and how to propitiate them:

Another hundred miles east is Green Hill Mountain. On its south side is much jade; on its north side is much azurite. There is an animal here with the shape of a fox with nine tails. It makes a sound like a baby and devours men. By caring it, one can avoid evil forces. There is a bird here with the form of a dove. It makes a sound like men shouting. Its name is the Kuan-kuan. Wearing it at the waist will prevent delusions. The Ying River issues forth from here and flows south into the Chi-i Marsh. There are many red ju -fish, which have the form of a fish with a human face. They make sounds like mandarin ducks. Eating them will prevent skin disease. . . . The gods are in the form of birds with dragon heads. The proper sacrifice uses animals with hair and a jade chang -blade, which are buried. The rice offering uses glutinous rice, a jade pi -disc, and hulled rice. White chien -straw is used for mats.[35]

Those routes through surrounding regions termed "Great Wilds" (Tahuang ) contain a wealth of early mythology about the bizarre peoples and strange gods who inhabit these distant zones (fig. 5):

In the Great Wilds of the West there is a mountain named Ao-ao-chü, where the sun and moon set. There is an animal here with heads on the right and left named the P'ing-p'eng. There is Shaman Mountain. There is Valley Mountain. There is Golden Gate Mountain and a person named Huang-chi's Corpse. There are single-wing birds who fly in pairs. There is a white bird with green wings, yellow tail, and a black beak. There is a red dog called Celestial Dog. Wherever he descends, war occurs. South of the Western Sea at the edge of the Shifting Sands beyond the Red River and before the Black River is a great mountain called K'un-lun. There is a god with the face of a human and the body of a tiger, with a white spotted tail, who lives here. Below, the depths of the Weak River surrounds the

mountain; beyond is Fiery Mountain. Anything that is tossed up there bursts into flames. There is a person there who wears a headdress, has tiger teeth, the tail of a leopard, and lives in a cave named Queen Mother of the West. This mountain contains every kind of object. . . .[36]

The traveler of the Guideways is never personified and can only be read as a function of the itineraries. In the chapters on relatively familiar territory, the care given to describe sacrificial offerings reveals a world in which the naive traveler is at risk unless he performs the proper rituals. In the chapters on the Great Wilds, by contrast, the prospective traveler is given no advice concerning sacrifices, and the routes in these chapters seem poorly defined, even unfeasible. For later readers, such as the lyric poet T'ao Ch'ien (365–427), it was precisely the exoticism of such territories that appealed to them, stimulating their fascination with the strange.[37]

Fundamental historiographical frames of time and space in both these texts reappear as regular features of later travel writing. The Chronicle of Mu employs the chronology of the "horary sterns" system, which encloses linear sequences within recurring cycles.[38] The Guideways utilizes the simplest way of representing spatial progression as a string of spheres—mountains or territories linked by a single road. In addition, the Guideways describes each mountain in the chapters on familiar territory using exactly the same categories of key features, thus creating a rhythmic repetition, an illusion of control over Nature in which the danger of the unexpected is absent and unseen spirits can be managed. In later travel writing, the tendency for writers to select the same categories of objects for scrutiny and conventionalize the basic elements of a scene can be read as a similar effort to enclose and order the world. Compared to their Western counterparts, later Chinese travel writers described remarkably few irrational, terrifying landscapes, bizarre or grotesque experiences, or journeys of unremitting physical suffering.

During this early phase, classical philosophers of the later Chou dynasty defined some of the basic ideological meanings of travel, meanings that continued to guide the perceptions of later writers. The Confucian school and the writer(s) of the "Inner Chapters" of the Chuang-tzu in particular asserted complementary visions of how travel affected moral and spiritual perceptions of the Tao , the nature of Nature and the ways of being in it, as well as the role of language.

Classical Confucianism articulated several views about travel from the standpoint of its program of self-cultivation and ruling the world.

Fig. 5.

Some Inhabitants of the Great Wilds from Guideways through Mountains and Seas . From Shan-hai ching (Shanghai, Kuang-i shu-chü ed., n.d.).

Early versions of the text were accompanied by illustrations that were lost and periodically redrawn over the centuries.

Those shown here date from the first half of the twentieth century.

As an ideology, Confucianism arose to reverse the disintegration of the centralized Chou feudal system due to the rapid mobility of new local elites. Order was to be restored by educating a ruling class of morally aware "Noble Men" (chün-tzu ) who would reinstitute the patterns of ritual behavior (li ) of the idealized sage-kings of the early Chou and remote antiquity. Li was largely antithetical to any concept of spontaneous, unconstrained movement based on personal desire. Travel by a ruler could be justified only as a pragmatic extension of the moral Tao from the political center—hence The Tso Commentary's critique of Emperor Mu. Confucius (551–479 B.C.) himself is quoted implying that Mu's desire to travel was a failure of the ruler to practice humaneness (jen ) by "restraining the self and returning to li " (k'o-chi fu-li ), which could have had dire consequences for the state.[39] Confucius's own peregrinations in search of an enlightened ruler who would employ him have a negative connotation too: he traveled only because the world was in chaos, seeking to find his proper place in a stable power center. To the extent that perfect Confucian government was associated with temporal repetition of moral activity and the spatial stability of its rulers, purely personal travel in the context of statecraft was synonymous with destabilization and a loosening of the bonds of li .

The Confucius of The Analects (Lun-yü ), however, found positive value in limited excursions into Nature to discover scenes of moral symbols that would illuminate the ideal qualities of the Noble Man. In what is perhaps the line most quoted in later Chinese travel writing, he said: "The wise man delights in streams; the humane man delights in mountains."[40] This view of the self reading its perfected image in the landscape is a basic assumption that underlies not only Confucian but also later lyrical modes of travel writing. Indeed, this statement was often appropriated by later writers to defend their private, pleasurable journeys as proper acts of self-cultivation. Nevertheless, Confucius did not view Nature as an alternate sphere of subjective feeling within which the traveler could transcend the political world; his concept of "beauty" (shan ) identified the aesthetic with the morally good. The landscape for him was thus a didactic scene where the Noble Man prepared himself for his proper role as a ruler at the center of the sociopolitical world.[41]

Related to the discovery in Nature of a mirror of the moral self is the idea that certain scenic views can provide a total perspective on the world. The Mencius (Meng-tzu ) states that when Confucius climbed East Mountain (Tung-shan), he realized the relative insignificance of his home state of Lu; and when he climbed the Supreme Mountain (T'aishan), the empire appeared small.[42] For Chinese travel writers, the

ascension of mountains or other high points became a pervasive motif and often the climactic focus of their accounts. The descriptions were not of arduous conquests of death-defying heights, for most of the important Chinese mountains were well under six thousand feet, and even a hill, terrace, or pavilion might serve to provide the experience. Rather, the ascents were generally safe though sometimes demanding hikes to points offering scenic panoramas that writers represented as symbolic of an all-encompassing view of reality. The process of more grounded travel was often represented as yielding a series of partial perspectives indicative of the finitude of the human condition. But the heights of mountains were widely believed to be points of contact with Heaven itself, where the traveler could gain the "grand view" (takuan ).[43] When Fan Chung-yen (989–1052), in The Pavilion of Yüeh-yang (1046),* described the panorama of Grotto Lake (Tung-t'ing-hu) as a "grand view," for instance, or the Ming prime minister Chang Chücheng (1525–1582) wrote in Transverse Mountain* that he had climbed to the summit to gain a grand view of the world, each sought to present his journey as a quest for Confucian sagehood.

Confucius also articulated another issue that lay at the heart of the act of literary inscription: the correspondence of "name" (ming ) and "reality" (shih ). When asked what he would put first if given the administration of the state of Wei, he replied, "the rectification of names" (cheng-ming ),[44] which he saw as fundamental to speech and action as well as to the institutionalization of ritual and punishments. In Confucian ideology, such naming was seen as a core function of the ruling class, who would employ the classical language to recover the moral structure of the golden age of the sage-kings. The travel writer as a Noble Man rectifying names is a persona that appears in a number of texts, particularly the subgenre of the "valedictory travel account." Beginning with Han Yü's (768–824) celebration of a fellow exile's character in The Pavilion of Joyous Feasts (804),* many writers inscribed the landscape as a scene of individual virtue, thereby seeking to praise worthy men, redress injustice, or restore the historical record while simultaneously constituting themselves as loyal Confucians. A frequent pattern at least since Yüan Chieh's (719–772) The Right-hand Stream (ca. 765)* is the encounter of a traveler with a hitherto undiscovered or unappreciated scene, followed by his lyrical response to it and, finally, his appropriate naming of it.

In contrast to travel as a purposeful activity whose ultimate goal was the restoration of moral and political order, the Chuang-tzu presents travel as liberation from the unnatural constraints of society, a spiritualized venturing forth into the unrestricted realm of authentic

being (tzu-jan ) much like the self-generated movement of the Tao . If the purpose of the Confucian itinerary can be summed up in the ideals of self-cultivation and ruling the world, the phrase "free and easy wandering" (hsiao-yao yu )—the title of the first chapter of this work—became the bywords of all who, following the Chuang-tzu , sought escape from the strife of the dynastic scene. In a number of fables, tropes of floating on the wind or down a river serve to convey man's natural, effortless participation in the Tao . Many of the characters are described as constantly on the move. The gigantic p'eng -bird metamorphoses from the k'un -fish and flies from the northern darkness to the Celestial Lake in the south, a trope for the continuum of the Tao as ongoing transformation and bipolar alternation. Images of water occupy a particularly important role in the Chuang-tzu . In the chapter "Autumn Floods" (Ch'iu-shui ), the relativism of all perspectives is comprehended by the Lord of the Yellow River, who flows into the even vaster North Sea and realizes the limitations of his existing mental parameters. This fundamental relativism perceived from a shifting ground on Earth is the Chuang-tzu 's alternative to the "grand view," which for Confucius emerged from an ascent to a fixed point on the border of Heaven.

Of the modes of "free and easy wandering," that which is unconscious is asserted to be the highest. Even the Taoist philosopher Liehtzu is criticized for relying on a dependent mode of travel—he uses the wind—instead of on "unwilled activity" (wu-wei ). Characteristically, those who achieve this mode are not dominating emperors or upright Confucians but lowlife figures such as millipedes, snakes, and shadows. The Ckuang-tzu even recommends travel as the solution to the impediments of human reason. When the logician Hui-tzu is unable to figure out a practical use for a huge gourd, Chuang-tzu recommends that he use it to "go floating around the rivers and lakes. "[45]

Both Confucius and the writer(s) of the Chuang-tzu would have agreed that the way of being in a place was more important than regarding the place as a destination. They relied on the myths of a golden age in antiquity and saw travel as facilitating a return to original human nature. These attitudes may explain, in part, why the quest is less significant in Chinese travel writing than in Western travel writing, and why many journeys are represented as ramblings that produce casual perceptions and insights rather than as roads to a specific object of power. As an alternate vision to Confucian ideology, the Chuang-tzu remained an influential text in Chinese culture, reaffirming a self-centered view of travel. Moreover, despite the Chuang-tzu 's antipathy to language as unstable and incapable of accurate signification, it in-

spired many later works of lyrical travel literature in which writers sought to describe a sense of freedom anti contentment found in the landscape of the natural Tao .

During the Ch'in and Han dynasties, the kind of ritual progresses earlier recorded in The Book of Documents and The Chronicle: of Mu were officially documented by Han historians. Following the extensive tours of the First Emperor of Ch'in (r. 221–210 B.C.), numerous Han emperors made visits to the sacred mounts and other sites ruled by gods.[46] Wizards (fang-shih ), who proliferated during this period, were recorded as journeying to make contact with Transcendents (hsien ), elusive figures who had discovered the secret of longevity and had etherealized into spiritual energies so they might freely wander through time and space.[47] These wizards then influenced credulous emperors to leave the capital and make arduous pilgrimages to sacred mounts and rivers in the hope of encountering Transcendents.[48]

Ma Ti-po's A Record of the Feng and Shan Sacrifices (A.D. 56)* records the pilgrimage of the Eastern Han emperor Kuang-wu (r. A.D. 25–57) to the Supreme Mountain near the end of his life. It is the earliest extant account of an actual journey written by the traveler himself and was considered by the Ch'ing scholar Yü Yüeh (1821–1907) to be the first travel diary.[49] Though separated from the travel account of the T'ang by seven centuries, it surprisingly contains many of the same rhetorical features. This ritual tour had the dual agenda of sacrificing to Heaven and Earth and enhancing the emperor's longevity, for wizards had convinced him that the Yellow Emperor had succeeded in just such a quest in antiquity. The account, which was probably prepared as an official report, was presented through the eyes of its author, Ma Ti-po, an official who preceded the emperor to make arrangements. It demystitles the idealized itineraria by not recording the emperor as having encountered any spiritual beings. In fact, far from extending his life, one year after returning to the capital he died. This unique exemplar suggests that writers in the Han may have already developed first-person travel writing, and reveals the incompleteness of our knowledge of the corpus of early Chinese literature given the limited number of surviving texts.

Early Chinese writers represented the journey primarily in poetry rather than prose, as seen particularly in the Ch'u tz'u collection of the Warring States period and the fu rhapsody of the Han and Six Dynasties. A number of poems of the Ch'u tz'u codified around the first century B.C. are transformations of religious material in which a shaman or wizard embarks on a spirit-journey to the supernatural. In "Nine Songs" (Chiu-ko ), the shaman is in quest of gods and goddesses who

may or may not appear. A similar goal stirs the more successful quester of "The Far-off Journey" (Yüan-yu ), who follows a circular course through the symmetrical cosmos of Hah Taoism, where he communes with the gods of each sector, finally achieving a climactic apotheosis in the center.

In "On Encountering Sorrow" (Li sao ), Ch'ü Yüan (340?–278 B.C.), a Ch'u nobleman slandered by rivals and disillusioned with court politics, ascends in a chariot and travels to mystical realms in search of an allegorical "Fair One" (mei-jen ), a virtuous figure who will understand him. Yet his search proves fruitless; even allies sought among spirits and shamans fail to guide him. The influence of this particular poem on lyric travel writing was considerable: indeed, it was traditionally regarded as the locus classicus of tragic experience in literature, of unsatisfied questing, and of the expression of plaintive emotions. The writer of "On Encountering Sorrow," in the end, was unable to view Nature as a mirror of personal virtue, a scene of transformation, or a soothing refuge. The environments he visited prove to be merely extensions of his anguished sorrow and feelings of misunderstanding.[50]

With the political and ideological consolidation of the Han dynasty during the second century B.C., a systematic cosmology was defined, an intricately structured map of overlapping dimensions. Elements existing in spiritual, historical, mythical, geographical, political, moral, and bodily zones were believed linked by elaborate correspondences and were brought into conjunction with one another through events of sympathetic response.[51] The fu rhapsody developed largely as a courtly celebration of this universal order, and it often employed the framework of the journey to survey and catalog this manifold reality.[52] Some pieces provide detailed descriptions of the landscape, while others focus on various natural phenomena, supporting the view that the rhapsody was an origin for what some Chinese critics have termed "landscape literature" (shan-shui wen-hsüeh ).[53] Later, travels to the frontiers and to lesser cities, sightseeing from famous towers, celebrations of outstanding buildings, and descriptions of mountains and rivers became the subjects of simpler, more personal rhapsodies not necessarily intended for the court.

Among the outstanding fu rhapsodies on distant travel were Pan Piao's (A.D. 3–54) Rhapsody on a Northward Journey (Pei-cheng fu , A.D. 25), Pan Chao's Rhapsody on an Eastward Journey (Tung-cheng fu , A.D. 95), and P'an Yüeh's (247–300) consummate Rhapsody on a Westward Journey (Hsi-cheng fu , 292).[54] These journeys were undertaken respectively to flee a civil war, to take up an official post, and to escape political persecution. All three pieces, however, treat the journey as a

setting for what Hans Frankel has called "contemplating antiquity" (lan-ku ).[55] In these works, a string of sites evokes melancholy reflections on such themes as ruined cities, the cruelty of past rulers, the loneliness of the traveler away from home, the moral heroism of ancient worthies, and the writer's personal fate. The actual narrative of the journey itself and the objective description of the landscape play relatively small roles in these later rhapsodies. Rather, they serve as a framework for reflections on moral history. Each site is perceived as connected to personalities and events that in turn provoke emotions and judgments on the part of the writer, who mostly wears the mask of the historian. These later travel rhapsodies represent an advance in realism over the earlier courtly pieces. While still utilizing parallelism and allusive language, they no longer celebrate a well-ordered cosmos centered on the emperor. The journey marks the irony felt by the individual writer forced to travel, while his rectification of the past substitutes for the world he has lost.

A set of verbal techniques essential to both the Ch'u tz'u and the fu rhapsody was codified into a euphuistic style later termed "parallel prose" (p'ien-wen ). It became the most prestigious form of writing at court until the later dynasties and was utilized in both official documents and more literary endeavors.[56] Among the general features of parallel prose were the pervasive use of couplets of four or six characters that maintained metrical and syntactic parallelism, shifts in meter, and the use of binomial expressions and other euphonic devices. The lofty, often difficult diction utilized a dense texture of figuration and a host of learned allusions, conveying an aesthetic: of erudition, elegance, and courtliness. Complementarity was the most apparent feature of parallel prose. The correlation of signs into two mutually implicating, polar categories formed a powerful rhetorical device for representing totality and still underlies profound patterns of thought present throughout Chinese culture. The very concept of hindscape, shan-shui —literally, "mountain-water"—depended on such a perceived parallelism in Nature, within which the traveler was situated. Other polarities such as Heaven and Earth, yin and yang , past and present, capital and wilderness, constituted archetypal axes that travel writers employed to chart their journeys through the world.

One result of this emphasis on spatial representation is that the actual journey to a place is often not crucial and may not even be mentioned as such, while striking features in the landscape such as architecture, gardens, mountains, caves, or springs become the exclusive focus of interest. The reader may be told little about the rigors of the road, where the traveler spent the night, what he ate or whether it

agreed with him. How and why he arrived at his destination may be briefly noted at the beginning or end, or not at all. In Chinese travel writing, attention is usually placed instead on the pattern of shifting observations and responses to the environment. These are generally more important than a logical emplotment of change in the writer's status or personality as he proceeds from one point to another, as occurs in many Western narratives. Parallel prose can be found to varying extent in almost every travel account and diary, especially in descriptive passages. During this early period, it was notably employed throughout Pao Chao's (ca. 414–466) Letter to My Younger Sister from the Banks of Thunder Garrison (439).*

Toward the end of the Eastern Han dynasty, imperial power declined as nobles, local clans, and military commanders usurped authority. The empire fragmented into regional power centers, and the prestige of the court culture eroded. The complete collapse of the Han world order in the early third century, which was followed by three centuries of disunity, marked another important phase in the development of early travel writing. The succeeding Six Dynasties period was an age of mass migrations and unstable political centers. The fall of the Western Chin in 316 marked the beginning of a split between north and south that was to last for two centuries. When the non-Chinese T'o-pa tribe conquered the north, native Chinese aristocrats and many among the general population were forced to flee to the safety of the Long River (Ch'ang-chiang; also Yangtze) area. In the south, a similar series of weak dynasties preserved some of the purer elements of the southern and the displaced northern Chinese cultures. All the dynasties of this period were plagued by an inability to expand their territory militarily and by bloody internal competitions for power.

The result was the rise of localized aristocratic cultures in which talented individuals searched for universal meanings beyond the Confucian moral and political vision. Buddhist and Taoist forms of spiritual cultivation spread, influencing a broad segment of cultural forms. Among writers, transcendence, individual consciousness, and aesthetic appreciation became major preoccupations of various cults that celebrated Nature. "Mystical Learning" (Hsüan-hsüeh ) sought to redefine a cosmology built on the responsive relationship between man and the natural universe, a relationship that enabled the individual to find personal meaning and pursue techniques of life extension.[57] A new attitude toward the world was adopted by many among the literate, one defined by the avoidance of mundane affairs. "Pure Discourse" (Ch'ingt'an ) became a new mode of defining reality through metaphysical speculation about the larger questions of time, space, human emotions,

and mortality;[58] it was expressed in elite social circles by individualistic, even eccentric personal styles and in a genre known as "mystical poetry" (hsüan-yen shih ). Both Wang Hsi-chih's Preface to Collected Poems from the Orchid Pavilion (353)* and the anonymous Preface and Poems on a Journey to Stone Gate (400)* are the results of group outings that yielded enlightening reflections in these modes. The former is a melancholy pondering of time and mortality on the occasion of a poetic gathering of outstanding talents by a stream. The latter narrates a rapturous encounter of religious devotees with the scenery of Hermitage Mountain (Lu-shan), a major center of Buddhist and Taoist activity. Both these pieces were written in the form of a "preface" (hsü ), a short prose introduction to a poem or a collection of poems that often provides a narrative context.

Painting and painting criticism became meaningful adjuncts to travel writing because of the growing interest in depicting landscapes. The painting critic and Buddhist layman Tsung Ping (375–443), for example, was associated with the ethos of Hermitage Mountain. His theory, which has been termed "Landscape Buddhism," viewed mountains as no longer fearful zones ruled by spirits but as scenes of enlightenment. He regarded painted landscapes as substitute aids to meditation, icons that conveyed through similitude the spiritual truth to be found in Nature.[59] In old age, he relied on paintings to generate the experience of the landscape, what the Chinese call "recumbent traveling" (wo-yu ), a term signifying vicarious journeys through texts and images.

Literary criticism, another phenomenon that developed during this period, stressed the importance of Nature as a source of both inspiration and aesthetic criteria for the writer. Lu Chi's (261–303) "Rhapsody on Literature" (Wen-fu ) and Liu Hsieh's (ca. 465–ca. 520) The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons (Wen-hsin tiao-lung ) defined a metaphysical basis for writing as the embodiment of the patterns of the Tao manifest in the natural world.[60] Writing about the sensory patterns of the universe perceived by the spiritual mind in sympathetic response to the sun, moon, mountains, and streams was, in Liu's view, to transmit a divine power possessed by sages.

But it was with the rise of a new kind of shih poetry—subjective, private, obsessed with transcending politics and with finding an alternative sphere for the self—that the Chinese lyrical impulse began to achieve its classic expression. Just as painting stressed resemblance in representation, the shih poetry of the Six Dynasties made scenic description a touchstone of the poet's talent.[61] Liu Hsieh devoted specific attention to the aesthetics of capturing Nature in language in his chapter entitled "The Physical World" (Wu-se ),[62] while another critic,

Chung Hung (ca. 465–518), employed descriptive ability as a criterion in ranking poets in his Evaluation of Poetry (Shih-p'in , 513–517). Both men referred to this tendency as "responding to things" (kan-wu ), a phrase that came to denote a new subgenre of poetry. In poems that explored fantastic journeys, such as those about "wandering Transcendents" (yu-hsien ), as well as poems recounting actual travels, the landscape was systematically surveyed and scenes depicted with a new devotion to concrete detail.

Two pivotal poets, T'ao Ch'ien and Hsieh Ling-yün (385—443), inaugurated genres of lyric poetry that incorporated personal experience in Nature, providing a set of motivations and responses, a vocabulary and grammar of description, and structural patterns of movement that became conventional elements in later prose travel writing. Both figures also became celebrated in the literary culture as ardent travelers who turned to Nature when disillusioned with official life. T'ao is regarded by literary history as the founder of the "field and garden" genre of poetry (t'ien-yüan shih ). Rejecting the humiliations and dangers of political life in middle age, he resigned from office as a minor magistrate to return to an impoverished life of farming and excursions. T'ao reacted against the dominant tradition of literary embellishment by employing a simplified diction to create a poetic ideal of "natural freedom" (tzu-jan ) and contentment amid rural scenes. His fictional "Record of Peach Blossom Spring" (T'ao-hua-yüan chi ) parodied historical writing in documenting a fisherman's discovery of an ideal village that had preserved a primitive simplicity in its social life while isolated for centuries from historical change. Originally the preface to a poem, this piece became the most influential vision of utopia, to which later travel writers often alluded as they searched for their own ideal worlds.[63]

Another preface T'ao wrote to one of his travel poems, "An Outing to Zigzag Stream" (Yu hsieh-ch'uan ping-hsü ), can be read as a miniature travel account in itself; though still dependent on the poem for its justification, it is briefly descriptive of a journey in Nature:

On the fifth day of the first month in the year hsin-ch'ou [February 3, 401], the sky was clear and the weather was mild, while all Nature seemed beautiful. I went with a few neighbors on an outing to Zigzag Stream. Standing on the banks of the flowing current, we gazed beyond at the Many-storied Citadel. Bream and carp leapt in the twilight; seagulls soared about on the balmy drafts. Over there, South Mountain has long been famous—no need for us to exclaim its praises. As for the Many-storied Citadel here, nothing connects with it as it stands in solitary beauty

amid the marshes. We imagined the Divine Mountain far away and were delighted by its appropriate name. Since it was not enough simply to encounter all this, we wrote poems. We felt sorrow over the suns and moons gone by and mourned the years of our lives that keep on passing. Each of us inscribed our ages and hometowns so as to commemorate this occasion.[64]

T'ao was one of the first to create images of himself in his poetry and prose, advancing the art of autobiography.[65] As a result of the enduring appeal of these images, he became an idealized figure for many later travel writers, who sought to emulate his detachment from the political world and his achievement of a sublime, natural existence. When K'ung Shang-jen (1648–1718), in Stone Gate Mountain (1678),* cited a poem by T'ao to describe his own feelings of satisfaction on having escaped the burdens of the city, he was following a long tradition of allusion to T'ao as a prototypical lyric traveler.

Hsieh Ling-yün's poetry is even more central to later travel writing, both for his self-image of the solitary traveler and for the structural pattern of the journey that he used in some of his most influential poems.[66] Regarded as the founder of "landscape poetry" (shan-shui shih ), he sought escape from the dangers and frustrations of political life in outings on his estate and the discovery of new landscapes. Unlike T'ao, the aristocratic Hsieh remained involved in the turbulent political life of the time, alternating between periods of service and disillusioned retirement. He also experienced exile and was finally executed while still relatively young. Most of Hsieh's landscape poems were written after a major political reversal when he was exiled to the scenic but isolated Yung-chia area in modern Che-chiang, and also during the periods when he withdrew from official life to his extensive family estate at Shih-ning (modern Shan-yu, Che-chiang).

Hsieh was an adventuresome traveler, always seeking out famous mountains in his vicinity, then trying to capture his sense of profound contact with their significant features in a style of verisimilitude. Many of these places serve as sites of self-effacement as the poet blends into a cosmic unity. In commenting on one of his most emblematic poems about the landscape of Shih-ning, "On My Way from South Hill to North Hill, I Glanced at the Scenery from the Lake" (Yü nan-shan wang pei-shan thing hu-chung chan-t'iao ), Kang-i Sun Chang has pointed out the parallelism between water and mountain scenes, plants and birds, and comprehensive and close-up views that were patterned into an ordered progression of continuously unfolding views.[67] Though still

indebted to the tradition of the fu rhapsody, Hsieh abandoned its hyperbole, courtliness, and formal rigidity. In the preface to his widely read "Rhapsody on Dwelling Among the Mountains" (Shan-chüfu ), in which he catalogs the natural beauty of his estate, he announces: "What I will rhapsodize about now is not the sumptuousness of capitals and cities, or palaces and towers, imperial tours and hunts, or music and beautiful women. I will only describe mountains and plains, plants and trees, streams and rocks. . . ."[68]

Hsieh also produced a work of short entries in prose about sites he had visited, Travels to Famous Mountains (Yu minx-shan chih ).[69] This text was originally substantial enough to circulate on its own, but disappeared sometime after the Sung and now exists only as a preface and some fragmentary notes. Apparently, it was gradually compiled between about 422 and 432. The extant entries cover mountains in modern Che-chiang and Chiang-hsi that correspond to many described in his poems. Each entry is a one-line geographical description without any narrative elements or poetic observations. Yet the preface can be read as a credo of the Chinese literary traveler who preferred the search for natural beauty to the dangers of politics:

Food and clothing are necessities of life; mountains and streams are what human nature takes pleasure in. Now, I have abandoned the burden of such necessities and have embraced my human nature, which enjoys such pleasures. It is commonly avowed that the happiness enjoyed in elegant mansions is satisfying enough, while those who sleep on cliffs and wash in streams lack great ambitions and can only preserve their withered bodies. I say, "Not so!" The Noble Man possesses a love for things as well as the ability to rescue them. Only those with talent can control the tendency toward dissipation. Thus, there are those who will endure the circumstances in order to aid their fellow man. Yet how could the stage of fame and profit be more worthy than a place that is broad and pure? An emperor dropped the reins of his chariot at Caldron Lake to become a Transcendent; a crown prince relinquished control of his horse at Eminence Mountain. Moreover, the Vermilion Duke of T'ao bowed out as prime minister of Yüeh, and Marquis Liu yearned to leave the service of the Han dynasty. If you reason from this, it will all become clear.[70]

One of the influences of Hsieh Ling-yün's poetic persona of a solitary traveler is the relative absence of other people in the landscape. Compared to Western narratives, in which traveling companions and individuals met on the road are usually objects of considerable interest,

Chinese travel accounts mention other people infrequently and may even leave the impression that the traveler is the only one there.[71] Actually, as members of the elite, few writers ever traveled alone; besides companions, they often took along: servants to clear the way, carry baggage, arrange transportation, and cook. Hsieh himself was sometimes accompanied by a retinue of disciples and servants on his excursions at Shih-ning. Even so, people, if noted at all, are usually acknowledged in but a few words, with conversations tersely recorded in the impersonal language of classical Chinese; and local residents are mostly ignored, except for such stereotypical figures as fisherman, woodcutters, monks, farmers, or the occasional peasant. In geographical accounts of foreign lands, ethnographic customs are usually described as general habits of the population as a whole, rather than depicted in the actions of representative individuals.

Whereas Western travel writing, with its novelistic orientation, emphasizes social events and portraits of noteworthy characters, the poetic underpinnings of Chinese travel writing tend to stress objects and qualities perceived in the landscape. For this reason, the dividing line between landscape literature and "travel literature" (yu-chi wenhsüeh ) is often obscure. The former is usually descriptive of a single location, while the latter takes in more of the experience of the journey. Yet this is at best a relative distinction, and most prose pieces include something of both elements. In the end, such generic labels are often less suggestive of the formal qualities of a given piece; more is revealed by considering the occasion for which it was written and the audience it was intended for.

During the Six Dynasties period, few attempts were made to extend poetic lyricism into prose forms. But in addition to prefaces, prose descriptions of landscape exist in fragments of letters that survived in later anthologies. An example is Wu Chün's (469–519) "Letter to Sung Yüan-szu" (Yü Sung Yüan-szu shu ):

The wind and mist are both stilled; sky and mountains have become one color. I followed the current, swirling, letting it bear me to and fro. From Fu-yang to T'ung-lu[72] is more than thirty miles. These extraordinary mountains and fantastic streams are unsurpassed in all the world. The water is a clear blue throughout; the bottom, visible to a depth of a thousand chang . Fish swimming and the smallest stones can be clearly observed. The rapid flow is faster than an arrow; its ferocious waves seem to race ahead. On lofty mountains along both banks grow evergreens everywhere. Mountains supported by their mass compete to rise higher; together, they all soar into the distance. Struggling aloft, pointing straight up: hundreds,

thousands, have become high peaks. Waterfalls dash against the rocks emitting sounds of "ling-ling ; elegant birds call to each other in a poetry of "ying-ying ." Cicadas buzz ceaselessly in a thousand ways as monkeys utter a hundred cries without end. "Sparrow hawks soar to Heaven"[73] but gaze at these peaks and cease their ambitions; "those who would order the affairs of the world"[74] behold these valleys and forget about returning. A crossweave of branches covers the sky: though daylight, it is darker than dusk. Through sparse twigs that reflect the light, the sun is sometimes visible.[75]

While lyrical landscape poetry was developing predominantly among southern writers, monumental travel writing m the historiographical mode arose in the north and west. These texts went far beyond the minimal entries of the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas to incorporate a wide range of material including some personal experiences and observations. The Guide to Waterways with Commentary* by Li Tao-yüan (d. 527), for instance, expanded an earlier work into an encyclopedic guide to 1,389 waterways. Following itineraries along major rivers, the Guide not only documented geographical features but also included data from official histories, philosophical texts, biographies, epigraphs, supernatural tales, legends, and folk songs. In addition, Li offered personal observations and evocative descriptions of outstanding landscapes. Usually classified as a geographical work, the Guide was written to recapture a comprehensive sense of the Chinese world at a time when the country was politically divided. Li himself stated, like a true historian, that he was preserving antiquity. In the opinion of later critics such as Liu Hsi-tsai (1813–1881), some of the book's descriptive passages anticipated the travel accounts of Liu Tsung-y–an (773–819).[76]

Another important work was Yang Hsüan-chih's (n.d.) The Temples of Lo-yang (ca. 547), which inaugurated the genre of urban and architectural accounts.* [77] It is similar to the Guide in its accumulation of a wide range of information. In addition to detailed descriptions of more than seventy temples in this war-damaged ancient capital, it preserves much material on aspects of urban life in Lo-yang. Historical preservation was also a great motivation for Yang. He had been an official in the city before its destruction and abandonment in 534, and afterwards sought to describe it at the height of its glory. His was the first of a number of such works compiled by travelers about cities both lost and still in their prime.

Lastly, the Six Dynasties period saw the rise of geographical accounts by Buddhist monks who journeyed through western China and Central Asia on their pilgrimages to India. Fa Hsien's (ca. 334–420)

A Record of Buddhist Kingdoms (Fo-kuo chi , 416)[78] is one of the earliest examples of this genre. Such records were intended to serve both official and private purposes: as intelligence for the ruler and as guide-books for future pilgrims. All the above works of historiographical travel writing shared a common style: objective, third-person narrative; emphasis on factuality; and production based on the compilation and processing of a variety of information including other texts.

On the eve of the development of the lyric travel account in the T'ang, the primary discourses of objective, historiographical documentation and subjective, lyric expression already marked various narrative and poetic genres. Philosophical and religious ideologies emphasizing statecraft, moral cultivation, modes of being in Nature, and spiritual transcendence had become well established, and a private, nonofficial literature, together with theories of writing, had arisen. Early landscape painting also created parallels to literature that furthered the Chinese perception and cultural transformation of Nature. Yet genuine travel writing as the first-person narration of a journey still remained fragmented and subsumed within other genres. It required the particular situation of the literatus-official under the T'ang to generate the autobiographical and stylistic motivations for conveying the experience of traveling to a sympathetic audience. This was brought about in prose largely by two factors: the exigencies of political exile, and the advocacy of a new literary style designed to reassert the Confucian vision.

The Exilic Syndrome, Ancient Style Prose, and the Rise of the Lyric Travel Account

With the reunification of China under the Sui and T'ang dynasties, the centralizing forces in Chinese culture reasserted themselves to create a great empire that viewed itself as the successor to the Han. The borders were again extended to Central Asia, parts of modern Korea and Vietnam came under Chinese influence, and the Chinese settlement of the aboriginal areas south of the Long River was aggressively continued. The political system adapted past institutions to a centralized model and for a century managed to avoid the traditional evils of excessive taxation and a bloated bureaucracy: in 657, there were only 13,465 officials for a population of about fifty million.[79]

Like earlier dynasties, the T'ang drew the upper levels of the official class from aristocratic clans and other elite families, including those

whose forebears had served in the government.[80] Despite the expansion of the examination system, it accounted for only about 10 percent of officeholders and did not bring in many talented outsiders. Nor did the process of recommendation, a more flexible avenue of recruitment, fundamentally alter the social composition of the literate elite. The T'ang did, however, initiate one powerful trend that ultimately undermined the role of the aristocracy in China. For gradually, the power of the court "metropolitanized" members of the local aristocracies, attracting them away from their regional power bases. The central government now appointed all local officials instead of only the principal ones, who previously had chosen their own subordinates. Hence, the power of autocratic emperors and the imperial family grew in relation to other clans. This had a considerable effect on T'ang writers, most of whom were unable to envision a mode of existence apart from official life. Compared to writers during the Six Dynasties period, T'ang literati became more psychologically dependent on service to the dynasty and more subject to the whims of imperial power. Even when demoted, exiled, and disillusioned, as in the case of Wang Wei (701–761) or Po Chü-i, they were generally unwilling to renounce public service and withdraw completely into private life.

Travel writing during the first century of T'ang rule largely followed the practices established during the Six Dynasties. The geographical and ethnographic description of foreign kingdoms by Buddhist pilgrims reached its height in Hsüan-tsang's (ca. 600–664) A Record of the Western Region (646).* This work was of particular interest to the T'ang court, which had reopened the Silk Road and was actively engaged in military maneuvers designed to defend the heartland against such expansionist forces to the west as the Tibetans, Uighurs, and other Central Asian tribes. At court, the parallel prose style retained its prestige and was cultivated by ambitious writers in the provinces—as exemplified by the young Wang Po's (ca. 650–ca. 676) consummate description of scenery in his Preface to Poems from the Pavilion of the Prince of T'eng (675).* Encountering Nature on one's estate continued as a poetic theme. Wang Wei, for instance, immortalized the beauty of his estate, Wheel River (Wang-ch'uan), in a series of lyric poems, and further communicated these visions in prose in A Letter from the Mountains to the "Cultivated Talent" P'ei Ti .*

Painting and travel writing drew closer during the T'ang through developments in the representation of landscape and through increased journeys, both in provincial centers such as Tun-huang as well as in the capital.[81] As landscape subjects achieved greater independence from figure painting, the T'ang developed a sophisticated set of composi-