The Explosion Problem

Of all the hazards associated with grain handling, the most serious one is also the most difficult for those outside the grain business to understand. It is grain dust. This dust, generated whenever grain is handled, is easier to ignite and results in a more severe explosion than equal quantities of TNT. One insurance company distributes placards with the warning "Grain dust is like high explosives." Dust explosions account for the vast majority of personal injuries and property losses in grain-handling facilities. There are thousands of small fires in these facilities every year; estimates range from 2,970 to 11,000. But the twenty to thirty explosions a year account for almost 80 percent of the property damage and 95 percent of the fatalities[6] (see table 4). Making sense of these trends over time is complicated by the changing fortunes of the grain trade. The major explosions in 1977–78 coincided with tremendous increases in wheat exports (primarily to the Soviet Union). The comparatively low number of explosions in recent years, on the other hand, is attributable in part to decreases in grain sales.[7] Fluctuations in trade patterns notwithstanding, the explosion problem remains the most serious hazard in grain elevators.

Contrary to popular belief, explosions in grain elevators are not caused by spontaneous combustion. To cause an explosion, the dust must be mixed with air to form a dense cloud. (Layered dust only smolders upon ignition.) The airborne dust concentrations must also be above the lower explosive limit (LEL), a condition so opaque that visibility is minimal and breathing is difficult. Concentrations above the LEL occur regularly inside most bucket elevators (described below) but seldom elsewhere in a facility. Also contrary to popular belief, grain elevator explosions are not one big blast. They usually involve a primary explosion and a series of secondary ones.[8] The primary explosion generates shock waves throughout the elevator, often raising into sus-

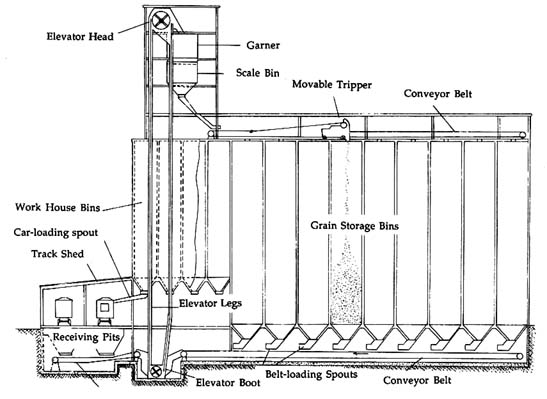

Figure 1. Terminal-Type Grain Elevator

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

pension layered dust on walls, rafters, equipment, and the floor. Accumulations of as little as one-hundredth of an inch will propagate the flame from an initial explosion. In other words, layered dust provides the fuel to turn a primary explosion—often itself quite minor—into a major one.

There are two basic schools of thought about how to approach the explosion hazard: one, eliminate ignition sources; two, control airborne and layered dust. Although it seems obvious that neither strategy should be pursued exclusively, the debate over safety standards is often between groups that have a strong preference for one approach.