Chapter 5

The Damned and the Blessed of the First Archivolt

The Damned and the Tortures of Hell

The scenes on the right, or south, side of the first archivolt (nos. XII–XV, Plates VIIIa and IXa) show the Damned and the tortures of Hell. An inscription incised into the outer beveled edge of the seven lower voussoirs reads: “S. J. BRUN, SCULPT. ELEVE DE LEMOT RESTAURA CE PORTAIL EN 1839.” In this century, Brun's signature has invariably been interpreted as proof that the entire portion of the inner archivolt, left, is a nineteenth-century invention. Yet the examination authenticated numerous twelfth-century details and confirmed Guilhermy's report: “Il restait quelques indications qu'on a suivies.”[1]

Twelve voussoirs contain the scenes of the Damned carved on their surfaces. Of those twelve, eight retain fragments of twelfth-century carving that guided Brun. Only the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh voussoirs from the bottom have scenes composed entirely of nineteenth-century insets. Of those, the figures on the fourth and seventh voussoirs follow the indications of twelfth-century fragments in the adjacent third and eighth voussoirs.

Seen from below, the turmoil of twisting bodies has the unmistakable appearance of a nineteenth-century restoration. Carved in four sections, the insets into those four voussoirs have joints that were easily identified from the scaffolding. Each nineteenth-century section was set with dowels and mortar in the original voussoir where a channel had been cut, which functioned as a mortise made to receive a tenon. As the diagram shows, in the fifth voussoir the inset also replaced the upper right section of the surface plane of the old stone. The restoration extends over to and includes some of the beveling along the outer edge.

The scenes of the Damned and Hell should be read from top to bottom: In the uppermost group (no. XII, Fig. 22 and Plate IXa), an angel is pushing a man-

Fig. 22.

Angel no. XII, first archivolt, right, fourth tier, detail, scenes of the Damned

acled soul away from Judgment and down toward the region of Hell (Plate VIIIa). Despite some distortion caused by repairs to the masonry joint as it crosses the angel's left knee, portions of the best-preserved drapery carving of the entire portal survive in the lower part of the figure. Recutting eliminated the lowest fold on the angel's left thigh and reduced the dimensions of the knee. Once perfectly symmetrical, the drapery over the two thighs still has a beautifully spaced series of curving folds of the type associated with Languedoc. Reflecting the motion implicit in the pose of the figure, the drapery of the tunic flares out above and between the lower legs in a series of pleats. The complicated hemline terminates each pleat in an intricate cluster of foldbacks. The angel's bony feet grip the surface plane; the crouched pose becomes anatomically plausible when read as an arrangement perpendicular to the surface of the voussoir block. With the restorations, the angel appears considerably foreshortened when viewed from below.

As diagrammed (Plate IXb), the recut areas include the surface of the under edge of the angel's right wing. Possibly a break occasioned the recutting, for the loss of the tip seems to have reduced the wing enough to make it appear somewhat undersized. Despite the damage repaired by nineteenth-century insets, as indicated in the diagram, this angel survives as a notable example of the style and quality of the original sculpture of the portal.[2]

Still visible on the stomach of the damned soul pushed by the angel, a fragment of the original chain authenticates the manacles around her wrists. The unrestored arrangement of the hair and her maidenly breasts establish the sex of this doomed soul. The inset repairing her legs not only follows the dictates

of the twelfth-century torso, but also connects with the original ankles carved from the voussoir directly below. Diminished only by light recutting near her left ear, the long, curling locks that reach to her waist survive from the original sculpture as a fine example of a twelfth-century coiffure for maidens.

The inset restoring the demon and the soul below in scene no. XIII follows the dictates of a generous vestige of the twelfth-century demon (Plate IXb). The original carving includes enough of his upper left arm to authenticate its raised position. Easily traced in its downward diagonal through his head and torso to the groin, the joining of the old and new stone then continues inconspicuously between the demon's thighs. A second inset forms the outer face of his left thigh and hip. The original left knee and lower leg survive, together with both twelfth-century feet. Clawed, with four birdlike toes, the feet probably provided the model for the hands and feet of the nineteenth-century demons below. A small, fleshy wing with large fish-scales over its surface sprouts from the demon's left heel. Except for that wing and the right foot below it, the extant twelfth-century surfaces all show some recutting. But the original fragments validate the pose and proportions of the demon which, together with his off-center placement, presuppose the second figure, which is most reasonably reconstructed as a damned soul whom the demon is dragging toward Hell.

Directly below, another twelfth-century fragment determined the placement and inverted position of the uppermost soul in group no. XIV (Plate VIIIb). Perfectly preserved, the right leg with foot kicking above the head of the demon joins the nineteenth-century figure at the groin. Notable for the modeling that articulates the bone structure of the knee and the musculature of the inner thigh, that leg has the same anatomically correct, rounded forms observed in the Resurrection frieze. The proportions of the leg demand a figure approximating the size of the restored body, and the pose presumes what the restoration has provided—a demon who is carrying a soul slung carelessly over his shoulder.

The beak-faced devil below and the two souls in his clutches have no authenticating twelfth-century vestiges, nor has the small soul carried by a demon on the right, directly above the crenellated parapet (nos. XIV and XV, Plate VIIIb). But on the left, the demon leaning over the parapet continues the activity assigned him by the surviving portion of his right arm hauling on the rope, also original, with which he is strangling the soul in torment below.

As the diagram shows, much of the original architecture of Hell survives as well as most of the soul in Hell and her tormenters: demons, viper, toad, and winged monsters. The left side of the building, the demon's arm, and even the rope escaped recutting. Elsewhere recutting proved negligible, except above the body of the lower winged beast on the right. There the wall of the building has been cut back so severely that none of the original surface carving survives. The wings of the beast also appear to be considerably reduced in size. All other insets follow the requirements of the twelfth-century sculpture, except for the grotesque faces in the left lancet. Yet they seem acceptable restorations, since they compare well with the original face peering out of the right lancet from beneath the belly of the monster. The notably well-preserved, coiled tail of that monster terminates in still another small face—an original conceit that has survived in good condition.

The lively tangle of tormenters at the foot of the wall creates the same kind of turbulence found above in the twelfth- and nineteenth-century arrangement of intertwined bodies. The turmoil of the lower composition gives additional credence to the not fully authenticated nineteenth-century portions. In the twelfth-century group, the viper coiled around the soul's right foot and the winged beast attacking from the opposite side seem to be pulling her limb from limb. The toad attacking her genitals adds the ultimate agony to her eternal torment. The lightly modeled figure of the soul, anatomically explicit and naturally proportioned, seems comparable in every way to the figures of the Resurrected Dead in the lintel zone (Fig. 11 and Plates IIIa and IVa). Lively and realistic, with feet twisted and braced, the agonized contortions of her legs reflect the several tortures she is suffering.

Paradise, the Blessed, and the Fifth Wise Virgin.

In contrast to the turmoil and disorder of the scenes of Hell, the scenes of Paradise, located on the inner archivolt to Christ's right, divide into three serene and discrete groups (nos. 5 and VI–VIII, Figs. 23 and 24 and Plates IIIa, VIa, and VIIa). Although critics have questioned the authenticity of that disparity, the examination of the scenes of Hell discussed above indicated that the continuous group of souls and demons tumbling into Hell retain at least the original outlines. In the feudal world of the twelfth century, order clearly symbolized

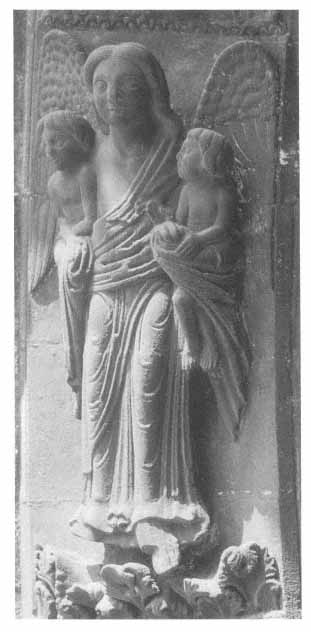

Fig. 23.

Detail of the Archangel “Gabriel” carrying souls, no. VII,

first archivolt, left, second tier

the state of the elect, whereas disorder was the fate of the outcast. The literal representation of those contrasting conditions in the first archivolt provides additional evidence of a preoccupation with didactic imagery in the Saint-Denis portal program.

The identification of the three heavenly scenes as well as their relative positions on the archivolt depend on passages in the gospels according to St. Luke and St. Matthew. Standing in the lintel zone of the tympanum near the open Gate to Paradise in the lowest tier, the fifth Wise Virgin (no. 5, Plate IIIa) is ready to go in with the bridegroom to the marriage (Matthew 25:10)—the metaphor for

Paradise and the destination of the Blessed.[3] Three of the elect have already entered through the gate (no. VI, Plate VIa). One stands in the open door; the other two are carried by angels. Directly above that group, an angel is holding two souls (no. VII, Fig. 23 and Plate VI). Perhaps he represents the Archangel Gabriel who stood before God (Luke 1:19), or possibly he is the unnamed angel who carried Lazarus to his eternal reward, since the third group depicts Abraham with three souls in his bosom (no. VIII, Fig. 24 and Plate VII). Another metaphor for Paradise, that imagery rests on the parable of the rich man Dives and the beggar Lazarus. Dives, “clothed in purple and fine linen…[had] feasted sumptuously every day,” but had shown no kindness toward the starving Lazarus, “who lay at his gate full of sores.” When they both died, Dives went to hell, but Lazarus “was carried by an angel into Abraham's bosom” (Luke 17:19–22).

The lowest, or first scene, showing the open gate and the Blessed within the Heavenly City, seems particularly interesting because of the architecture. In addition, the small nude figures, metaphorical representations of the human soul, provide a stylistic link with the figures of the Resurrected Dead in the lintel zone and with the soul in torment in Hell. As diagrammed (Plate VIb), the insets restoring the figures of the Blessed proved routine and noncontroversial in that they perpetuated the original arrangements. The positions of the four nineteenth-century heads accord with the alignments of the torsos and shoulders, but as usual, the facial style detracts from the visual effect. Except for the original but heavily recut face of the soul standing in the doorway, the recutting appeared light enough to be deemed negligible.

The architectural details that deserve special mention include the hardware of the doors, the depiction of mortar so heavily applied that it oozes out of the masonry joints in the abutments of the large lancets on the left, and the ornamental zigzag occupied by circles that surrounds the lancet—all realistic renderings based on observations. Then, in an unexpected reversion to stylization, the artist ornamented the stepped-back buttress on the left with rows of incised triangles—an architectural fantasy amusing for its juxtaposition with such accurate details as the pins of the horseshoe-shaped hinges upon which the gate swings. Although they are heavily encrusted and no longer sharply defined, similar triangles in series ornament the architecture of some of the baldachins above the Wise and Foolish Virgins on the jambs of the portal below.

Such small details help to forge the links between the sculpture of the inner archivolt and the figures on the left and right jambs—all attributable to the Angel Master (see Chapter 6).

The delicately modeled torso of the soul carried by the angel on the left reflects the same attitudes toward the human body, expressed in the lively, realistic figures of the Resurrected Dead. Although anatomically explicit, the figure of the soul filling the doorway to Paradise appears flatter, and the proportions seem less credible. Yet features common to the sculpture of the inner archivolt, jambs, and Resurrection frieze suggest that one artist, the Master of the Tympanum Angels, was responsible for all those iconographically related figures. The stylized drapery of the angels of the Heavenly City, although skimpy, also seems compatible with the drapery of the other archivolt angels, and their wings have the same form and characteristics as the wings carved by him; his hand and ideas seem to dominate those groups.

The Angel Master left his stylistic signature more prominently in the drapery of the Archangel “Gabriel” above, who is carrying two of the elect (no. VII, Fig. 23). As diagrammed (Plate VIb), a single inset replaced the upper portion of the angel as well as the torsos and heads of the two souls in his arms. Insets that once restored the toes on both of his feet have fallen away. Except along the hem, the original drapery shows no recutting and only negligible weathering. Every crease of the folds in the drapery across his torso ends in a teardrop-shaped depression. The artist, emphasizing the intricate patterns of the draperies, outlined the terminus of each depression by incising a line on the ridges of the folds. Generously spaced hook folds curve alternately from left to right down and across the angel's tubular legs. The bold vertical pleats in series framing his legs assist in the definition of their solid, unsubtle forms. The angel has the same short, stocky proportions that characterize the figures of the tympanum angels. The combination of drapery elements in the lower half of the figure expresses in broader terms the same conventions defining the V of the groin and thighs of the tympanum angel no. V (Plate IId). In the upper half of the “Gabriel” figure, the arrangement includes teardrop folds that help to locate his hands beneath the veil. Widely spaced, concentric U -shaped folds below his right hand and again below his right forearm have the Languedocian incised lines accenting the ridges. On both sides of the figure the scarf falls with deeply undercut, thick, folded-back edges. The heavy folds that circle below his

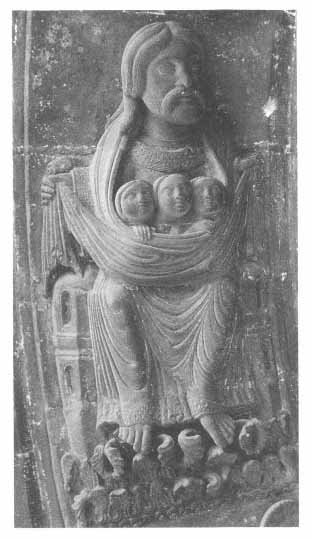

Fig. 24.

Abraham with three souls in his bosom, no. VIII, first

archivolt, left, third tier

left forearm swirl around his hand in a pattern reminiscent of the highly stylized right-knee drapery of angel no. XII in the scenes of the Damned (Fig. 22). Bolder, perhaps, with strongly stated curves and reverse curves, the arrangement underscores the forward projection of the forearm cradling the figure of the soul. In contrast with that highly stylized encircling drapery, the soul rests his tiny hand on the angel's arm in the easy, affectionate manner of a small child held in a mother's arms—the same gesture made by the soul on the left in the scene below.

The heavy, squat figure of Abraham occupies the third tier in the scenes of the Blessed (no. VIII, Fig. 24 and Plate VIIa). The stunted arms and fore-shortened thighs exaggerate the stocky proportions so evident in the “Gabriel” figure below, and they are also typical of the other figures attributable to the Master of the Tympanum Angels. Bonded at a masonry joint, the inset for

Abraham's modern head includes both shoulders and small portions of the decorated galon at the neck of his tunic. The heads of the three small souls in his bosom also belong to the nineteenth century. As diagrammed (Plate VIIb), other insets replace part of the lower portion of the hammock formed by the scarf, three toes of his right foot, and the tip of the scarf falling from his right hand. Slight recutting has affected the surfaces adjacent to the largest inset in the veil, the area along his left side below the left hand, and also most of the bench on the same side. The rest of the figure, although corroded by the weather and pollution, retains its original surfaces. Most of the minor repairs in mortar on the ridges of the folds of the lap drapery have crumbled and fallen away.

An original, small, delicately proportioned hand pokes out from beneath the chin of the soul on the right side of Abraham's bosom. That structurally accurate hand rests on the unnaturally thick edge of the scarf. The hammock formed by the scarf seems much too small to contain the three bodies presumed to occupy it. Paradoxically, the solid reality of the bulging swag and of the squat figure of Abraham is achieved by the interplay of curves created by a profusion of much-repeated, highly stylized folds. The multifold scarf caught up by Abraham's outstretched hands forms a festoon, and teardrop-shaped folds crease the scalloped loop of the scarf clutched in his right hand. Concentric folds with incised accents on the ridges define his lap from knee to knee and form a second festoon, which is completed by the fall of pleats on either side of the legs. The high-ridged, deeply creased side pleats differ from the less typical side pleats with fluted ridges flanking the legs of “Gabriel” below (no. VII, Fig. 23). Even more than in the recut hem of the latter, the pleats in Abraham's tunic flatten into ripples along the hem. In both figures, the hemline between the feet and the folded-back edges of the veils have the closed formation of the central fold-back associated with the Master of the Tympanum Angels. Well-preserved concentric folds define Abraham's lower left leg. With the concentric folds between the legs and the incised hook folds on the right shin, the multifolds by their very profusion mask the distortingly stumpy proportions of his legs and the minimal projection of his knees. Among the seated figures of the archivolts, this figure has no stylistic parallel.

Abraham's footrest with its especially succulent leaves shares an arrangement with the foliage of the two scenes below. Based on a repetition in tiers of a palmette motif, their plan differs from the centrally organized foliate designs

that prevail in the patriarchs' consoles (Figs. 33 and 34). Although variations on the palmette motif in the outer archivolts seem endless, the homogeneous organization of the foliate ornament below the three scenes of Paradise suggests a deliberate repetition of an arrangement in order to unify the scenes visually, and certainly points to the work of an artist other than the one responsible for the patriarchs (see Chapter 7). Along its base, Abraham's footrest has a continuous roll of compact scrolls, a modified version of the classical continuous-scroll motif. That minute decoration provides the only occurrence in the sculpture of the central portal of an abstract motif based on a classical or Antique pattern.[4] The foliage of “Gabriel's” footrest rises from a torus decorated with an arcade formed by leaves—another interesting and unusual ornamental detail.

The photographic detail of the restored tiers of foliage that form the footing for the Heavenly City (no. VI, Fig. 7) provides a perfect example of the techniques of the restoration and the deterioration caused by weather along the joints of insets. As described above, a comparison of the detail of the photograph with the diagram (Plate VIb) reveals discernible differences between the textures of the twelfth-century stone and the modern insets, as well as the surface modification in the old stone caused by even the lightest recutting.