Chapter Three

Legislative Imagery Under the Bourbon Restoration

When Louis XVIII returned to France in 1814, the tricolored flag carried by the armies of the Republic and the Empire was replaced by Bourbon white and the fleur-de-lis . Although the return to the old monarchic colors symbolized the identification with the Old Regime in France between 1814 and 1830, the Bourbon Restoration could hardly erase the previous quarter-century of French history. Imperial artists and politicians shifted their allegiance to the Bourbon monarchy, but the new regime maintained such Napoleonic institutions as the Council of State and the Legion of Honor. The Code Napoléon proved similarly durable, though it was shorn of its divorce provision and renamed Civil Code of the French People.[1] In granting a constitutional charter to the nation, Louis XVIII tacitly accepted the irreversibility of the Revolution. And by imitating the Napoleonic cult of the legislator the Restoration attempted to reinstate the Old Regime association of the law with monarchic will.

The preamble to the Bourbon Charter of 1814 exemplifies the Restorations explicit denial and implicit co-option of the modern French political tradition. Here the revolutionary discourse of reason, universality, natural rights, and the general will is silenced. In place of a Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen there is a reference to divine Providence, which, "recalling us [i.e., Louis XVIII] to our states after a long absence, has imposed on us great obligations." The 1814 charter, whose principles have been sought "in the French character and in the venerable monuments of past centuries," is dissociated from French history since 1789. For "we have effaced from our memory, as we would wish that one

could efface from history, all the misfortunes that have afflicted the fatherland during our absence." Instead, French monarchic judicial and administrative reforms are cited as precedents for modifying the exercise of the authority that "in France resides entirely in the person of the king."

The original draft of the preamble was provided by none other than Louis de Fontanes, who repudiated the revolutionary heritage with the same rhetorical flair he had shown so often in flattering Napoleon. His text deserves to be read in the original French:

Un pouvoir supérieur à celui des peuples et des monarques fit la société et jeta sur la face du monde des gouvernements divers: il faut plutôt en diriger la marche qu'en expliquer les principes. Plus leurs bases sont anciennes et plus elles sont vénérables; qui veut trop les chercher s'égare; qui les touche de trop prés devient imprudent et peut tout ébranler. Le sage les respect et baisse la vue devant cette auguste obscurité qui doit couvrir le mystère social comme les mystères religieux.

A power greater than peoples and monarchs made society and molded the different governments of the earth. It is our duty to manage them rather than to explain their principles. The older their foundations, the more we reverence them. Whoever tries too hard to understand them errs; whoever tampers with them imprudently can bring all to ruin. Whoever is wise respects them and bows before that majestic obscurity that must cloak both society and religion in mystery.[2]

Fontanes's rhetoric epitomizes that of critics of the Revolution under the Consulate and Empire who denigrated the eighteenth-century tradition of critical inquiry—Pierre-Simon Ballanche, for example, the Lyonnais mystic whose Du sentiment considéré dans ses rapports avec la littérature et les arts (1801) offered many of the same arguments as the later, but more famous, Génie du christianisme of Chateaubriand. Ballanche held that "the same divine power that reserves the right to establish and consolidate social institutions wanted to place their sacred constitution behind a veil that the hand of innovators cannot raise with impunity."[3]

The preamble to the 1814 charter—both in Fontanes's original draft and in Count Jean-Claude Beugnot's less pungent final version—testifies to the passage into mainstream French politics of the counter-revolutionary apology for throne

Fig. 27.

J.-L.-N. Jaley, Louis XVIII Granting the Constitutional

Charter , 1814, 1821. Musée de la Monnaie, Paris.

and altar articulated under the Consulate and Empire by Fontanes, Chateaubriand, and Bonald.[4] Fontanes's participation in drafting the preamble suggests his importance in providing ideological continuity between Napoleonic and Restoration France.

In accord with the Old Regime notion of the monarch as supreme legislator, the Charter of 1814 was granted (octroyé ) by Louis XVIII to his subjects. A commemorative medal by Jean-Louis-Nicolas Jaley (1802-1866) represented the official interpretation of this reform as an act of royal volition (Fig. 27).[5] It is instructive to compare this medal with a print commemorating Louis XVI's acceptance of the Constitution of 1791 (Fig. 28), a more innocent moment in French constitutional history. The print shows Louis XVI, hand on heart, vowing to maintain the constitution, held by a regal personification of France; in Jaley's medal France touches her breast in deference as she receives the charter from Louis XVIII. Whereas Louis XVI stands respectfully, virtuously, Louis XVIII sits enthroned, his severe countenance and exposed calf smacking of pre-revolutionary monarchic prerogative. Brenet's medal commemorating the Grand Sanhedrin (see Fig. 24) shows the legislator and recipient on similarly unequal footing.

The political history of the Bourbon Restoration was shaped by an uneasy compromise between the acceptance of constitutional reform and the assertion

Fig. 28.

F.-A. David after N. Lejeune, Louis XVI Solemnly Accepts the Constitution

at the National Assembly , September 14, 1791, 1791. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

of monarchic prerogative. Committed to the exercise of royal authority in accord with the constitutional charter, the regime stubbornly aspired to pre-revolutionary absolutism, an aspiration especially apparent after the coronation in 1824 of Louis's ultra-royalist brother, Charles X. To dignify this uncomfortable position, an iconography of divine legislation was employed in a cycle of paintings commissioned by the government to decorate four rooms in the Louvre that were remodeled in 1825 as new chambers for the Council of State.

The Council of State played an integral part in the conflict between constitutional legality and royal prerogative that colored politics under the Restoration. Deriving from the corps of professional administrators who counseled Old Regime monarchs and bearing the name of one of the principal cogs in Bonaparte's political machine, the Council of State was linked to both monarchic absolutism and Napoleonic authoritarianism.[6] Under the Restoration, it functioned outside the scope of constitutional control, offering advice to the cabinet of royal ministers and arbitrating administrative conflicts. The liberal opposition particularly disliked it, objecting to its extra-legal character.

When the Council of State was reorganized by an ordinance of August 26, 1824, it moved to the royal palace of the Louvre.[7] Because it was supposed to be presided over by the monarch, explained Minister of Justice and Keeper of the Seals Count Charles-Ignace de Peyronnet, "it is contrary to all decorum [contraire à toutes les convenances ] that this body assemble anywhere but in the palace of the king."[8] The ordinance, issued by a conservative ministry under Count Jean-Baptiste-Séraphin-Joseph de Villèle, was meant to reconcile royal authority with constitutional responsibility. The oath of new members of the Council of State was revised to include loyalty to the charter as well as the king, and the government was no longer to have the power, called destitution , to remove unwanted council members. A final exercise of this power, however, gave an ultra-royalist cast to the new Council of State.[9] According to François Guizot—who before becoming Louis-Philippe's prime minister was a member of the liberal opposition under the Restoration—such ambivalence was typical of Villèle, who always strove to attribute to the king both liberal opinions and those that recalled Old Regime absolutism.[10]

Under the direction of Viscount Louis-François-Sosthène de La Rochefoucauld, of the Department of Fine Arts, and Count Louis-Nicolas-Philippe-Auguste de Forbin, general director of the royal museums, the government

commissioned twenty-seven artists in 182.6 to provide paintings for the new chambers.[11] The painters—most now known only to specialists—included a number of Prix de Rome laureates as well as Eugène Delacroix, Ary Scheffer, and Paul Delaroche. In the opinion of the conservative critic Etienne-Jean Delécluze, the artists chosen were the "elite of the present school."[12] Two of the decorated ceilings remain visible, and a number of canvases are preserved in French provincial museums. In addition, many of the works were reproduced in the Musée de peinture et de sculpture . Together with the description of the ensemble in the Salon livret of 1827, these remains give an idea of the decorative program.[13]

Although visitors to the Salon of 1827 could view the new Council of State rooms, the decorations were intended for an elite audience. On the ceiling of the principal assembly hall is M.-J. Blondel's France, in the Midst of the Legislator Kings and French Jurisconsults, Receives the Constitutional Charter from Louis XVIII (Fig. 29).[14] The late Louis XVIII, avuncular but august, sits, with Wisdom, Prudence, Justice, and Law, high above the Seine on "the throne of his ancestors, to represent legitimacy" (pour caractériser la Légitimité).[15] At his feet a regal personification of France humbly receives the charter. The event transpires with a graciousness absent from Jaley's commemorative medal, which apparently served as Blondel's model (see Fig. 27). The monarchs and legists of the Old Regime looking on approve. Montesquieu and Henri IV (holding the Edict of Nantes) relax in the unlikely company of a delighted Louis XIV. To suggest the confidence inspired by the law, a putto sleeps on an open book inscribed CODE . A hostile critic remarked in the Journal du Commerce that "young France has armed itself against the arbitrariness of the ordinances and decisions of the Council of State, not by sleeping on the codes, but by studying them with perseverance."[16]

In associating the charter with divine will and traditional Bourbon largess, Blondel's ceiling painting echoes the sentiments of the charter's preamble. This didactic program continues in the coving, where monarchic precedents for the charter are illustrated in illusionistic bronze reliefs. Placed between Louis the Fat [Louis VII Chartering the First Town and Saint Louis [Louis IX] Granting the Pragmatic Sanction is The Spirit of Law Showing the Charter to Hope and Faith (Fig. 30). Here Christian virtues enact an unfamiliar constitutional pantomime. The Mosaic posturing of the putto Spirit of the Laws—like the obtrusively tangible anchor of Hope—points to that uncomfortable mixture of the literal and the ideal characteristic of late Davidian history painting. The unintentional

Fig. 29.

M.-J. Blondel, France, in the Midst of the Legislator

Kings and French Jurisconsults, Receives the

Constitutional Charter from Louis XVIII , 1827. Louvre, Paris.

Fig. 30.

M.-J. Blondel, The Spirit of Law Showing the Charter to Hope and Faith , 1827. Louvre, Paris.

comedy of this allegorical scene, moreover, hints at the shortcomings of the Bourbon Restoration's variant of the cult of law. "The Spirit [of the Laws] lacks inspiration," the critic from the Journal du Commerce noted, "and Faith seems to grimace as it beholds the book of our destiny."[17]

The royal throne in the room with Blondel's ceiling paintings symbolically referred to the king's presiding, by proxy, over the Council of State.[18] Never actually occupied, the throne serves as a reminder that Napoleon's energetic employment of the Council of State had no sequel under the Restoration; and it symbolizes the inability of the Bourbon regime to keep alive the Old Regime notion of the monarch as supreme legislator, triumphantly reinstated by Napoleon.

On the ceiling of the fourth room Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse rephrased in Bourbon terms the Napoleonic theme of divine legislative inspiration. In his Divine Wisdom Giving the Laws to the Kings and Legislators (Plate 5),[19] Moses, leading an encyclopedic host of legislators—including an Indian chief, George Washington, William Penn, Muhammad, and Confucius as well as Numa, Solon, and Lycurgus—receives the law from Divine Wisdom, whose entourage includes Prudence, Equity, and Clemency.[20] Envy and Calumny are banished by the sword as Louis XVIII and other French monarchs watch from the clouds.[21] The critic Auguste Jal, evidently hostile toward the regime, explained that Mauzaisse had gallantly separated the legislators from the French kings, not wanting "to mingle the very Christian kings with just any sort of people" (Le peintre n'a pas voulu confondre les rois très-chrétiens avec route sorte de gens).[22]

In its invocation of legendary, prototypical legislators, Mauzaisse's ceiling painting can be considered a Bourbon sequel to Moitte's relief group in the Cour Carré (see Fig. 19).[23] As in Blondel's ceiling painting, Mauzaisse reverts to the baroque allegorical tradition that seamlessly and felicitously links human events and acts of divine will. The persuasive power of the allegory, however, is blunted by a discursive specificity of historical and contemporary reference that lends an air of masquerade to Mauzaisse's legislators.

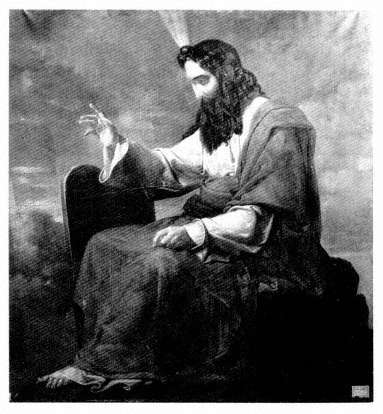

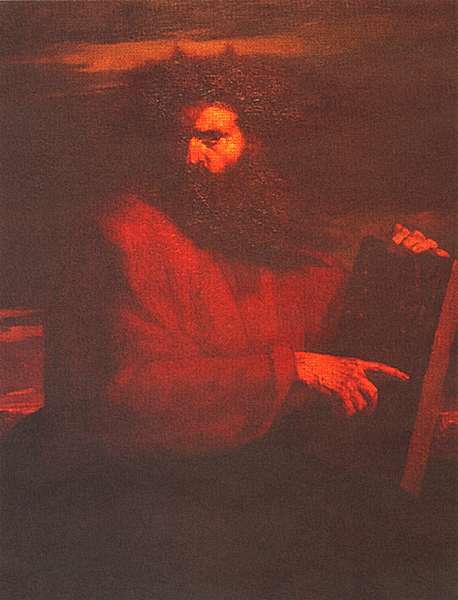

Legendary legislators as prototypes of the French monarch were repeatedly invoked in the Council of State rooms. Beneath Blondel's octagonal ceiling painting in the assembly hall hung his portraits of the divinely inspired legislators Lycurgus, Solon, Numa, and Moses—the last seated in stiff majesty like a salvador mundi (Fig. 31).[24]The Law Descends to the Earth, Establishes Her Domain, and Distributes Her Benefits , by Michel-Martin Drolling (1786-1851) is bordered

Fig. 31.

M.-J. Blondel, Moses , 1826-28. Louvre, Paris

(on deposit in the Musèe d'Histoire, Saint-Brieuc).

with roundels inscribed with the names Moses, Numa, Charlemagne, and Justinian (Fig. 32).[25] Below this chilly reprise of Guido Reni's Aurora hung Moses, Legislator (Michel Marigny; destroyed in the Palais d'Orsay fire, 1871), Numa Giving Laws to the Romans (Léon Cogniet; Montbéliard), Charlemagne Presenting the Capitularies to the Assembly of Francs (Ary Scheffer; Versailles), and Emperor Justinian Drafting His Laws (Delacroix).

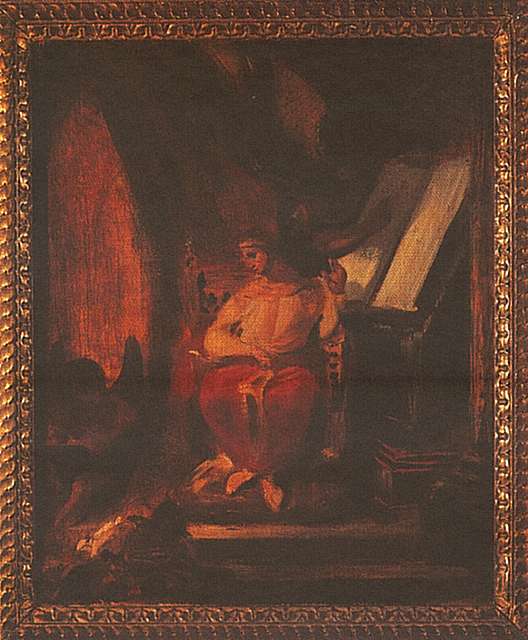

Delacroix's large canvas (3.71 x 2.76 meters; lost in the Palais d'Orsay fire, 1871) is known from an old photograph and from a superb sketch of 1826-27 in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Plate 6).[26] The enthroned Justinian, inspired by an angel and dictating to a scribe, is based on traditional representations of the

Fig. 32.

M.-M. Drolling, The Law Descends to the Earth,

1827. Louvre, Paris (no longer visible).

Evangelists. The emphatic gestures, bold chiaroscuro, and warm tonality of the sketch suggest that Delacroix brought to this motif an operatic amplitude and a material opulence that recall the contemporary Death of Sardanapalus . Justinian's extravagantly stylized pose suggests at once the flux of inspiration and the aloof authority of the lawgiver. Contemporary accounts of the lost painting speak of jewel-encrusted draperies that must have made the Justinian seem all the more remote and exotic. Delacroix's representation of the attributes of divine inspiration seems deliberate, for Justinian himself was principally a compiler and codifier of earlier Roman law. But the emphasis on the divine origins of law was also in keeping with the decorative cycle for which the work was painted.

The ancient lawgivers honored in the Council of State rooms were complemented by Saint Louis Rendering Justice under the Oak of Vincennes (Fig. 33) by Georges Rouget (1784-1869).[27] Illustrating the traditional doctrine maintained by the Charter of 1814 (art. 57) that "all justice emanates from the king," the painting shows Louis IX calmly executing justice amid a reverential audience. Similarly, two paintings in the first room, The Clemency of Augustus toward Cinna and His Accomplices (Pierre Bouillon; destroyed in Saint-Malo during World War II) and The Act of Clemency of Marcus Aurelius toward the Rebels of His Asian Provinces (Alexandre-Charles Guillemot; destroyed in Saint-Malo during World War II) provided antique exemplars of the royal power to grant clemency preserved by the charter (art. 67)—a prerogative all the more precious in the wake of a quarter-century of civil and political strife. Illustrations of heroic Old Regime magistrates refer obliquely to the violence of recent French history. Among these was the most admired work of the cycle, Paul Delaroche's pathos-ridden Death of President Duranti (destroyed in the Palais d'Orsay fire, 1871).[28]

In invoking divinely inspired legislators and glorifying the Bourbon monarchy, the decorative program of the Council of State rooms embodied the aspiration of the regime to bolster the authority of the monarch.[29] Notwithstanding the splendor of Delacroix's Justinian and the poignant theatrics of Delaroche's Death of President Duranti , this pompous, redundant program has a hollow ring that suggests not only the weakness of Restoration history painting but also the disparity between the triumphant rhetoric of the preamble to the Charter of 1814 and the vulnerability of this post-Napoleonic constitutional monarchy.

Given the resurgence of piety under the Restoration, it is not surprising that Moses, who occupies a place of honor in Mauzaisse's ceiling painting for the Council of State, was an attractive legislative motif after 1814. This appeal was all the greater because of the flowering during the Restoration of the infatuation with the Bible introduced by the Génie du christianisme . Encouraged by the new edition of the Bible by Antoine-Eugène Genoude, the young poets Alphonse de Lamartine and Victor Hugo came of age intoxicated by Scripture.[30]

Because the Bible vogue was often allied to counter-revolutionary themes, the Republican songwriter Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780-1857) denounced it, describing its practitioners as "bards inspired by the cashbox . . . [and] perfumers of the crown."[31] Such mockery would hardly have amused the young ultra-royalist Victor Hugo, who, according to his wife, wrote in a journal in 1816 that his

Fig. 33.

G. Rouget, Saint Louis Rendering Justice under the Oak of

Vincennes , 1826. Musée National du Château de Versailles.

Fig. 34.

L.-T. Turpin de Crissé, Messe à la Chapelle Expiatoire , 1835. Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

ambition was to be "Chateaubriand or nothing."[32] Bonald's Législation primitive , with its elevation of Moses and the Ten Commandments at the expense of the revolutionary legislative tradition, foreshadowed the political significance of Mosaic imagery in this reactionary climate.

The roundheaded tablets of the law were reconverted to Catholicism and stripped of association with the rights of man in the hushed interior of the Expiatory Chapel (1816-24), which Chateaubriand thought "perhaps the most remarkable" building in Paris.[33] It had been constructed, with Chateaubriand's blessings, by the former imperial architect Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (1762-1853) on the site of the cemetery of the Madeleine, which, during the Revolution, had received the remains of Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette, and other distinguished victims of the guillotine.[34]

Inside the chapel's severely classical central space, The Apotheosis of Louis XVI (1825) and Marie-Antoinette Succored by Religion (c. 1825) by the former imperial sculptors François-Joseph Bosio and Jean-Pierre Curtot lend grandeur to the fate of the royal couple. The base of The Apotheosis of Louis XVI is inscribed with Louis's profession of faith in the "commandments of God, . . . the sacraments, and the mysteries, such as the Catholic Church teaches them." The pendentives overhead bear emblematic relief sculptures by François-Antoine Gérard (1760-1843) that represent, according to the architect, "the four principal signs of our religion."[35] In one of these—visible in the meticulous rendering of the chapel in use by Lancélot-Théodore Turpin de Crissé (1781-1859)—Mosaic tablets in a glory are flanked by angels with attributes of martyrdom and immortality (Fig. 34). The Latin inscription beneath speaks of Christian duty: IF YOU WISH TO ENTER LIFE YOU MUST SERVE .[36] The revolutionary association of Mosaic tablets with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen lends poignance to this inscription, recalling Bonald's insistence on the sacrifice of individual rights to the duties owed to society and religion. "After long and bloody errors," Bonald concluded as he reflected on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, "one realizes that it is necessary to speak to man a little less of his rights, a little more of his duties."[37]

Bonald was pleased when Lamartine dedicated to him "Le Génie" (1817), published in Méditations poétiques three years later.[38] In his poem Lamartine compared Bonald's revelation of the sacred and immutable foundations of society to Moses' reception of the law on Mount Sinai:

Ainsi, quand parmi les tempêtes,

Au summet brûlant du Sina,

Jadis le plus grand des prophèes

Gravait les tables de Juda;

Pendant cet entretien sublime,

Un nuage couvrait le cime

Du mont inaccessible aux yeux,

Et, tremblant aux coups du tonnerre,

Juda, couché dans la poussiére,

Vit ses lois descendre des cieux.

Ainsi des sophistes célébres

Dissipant les fausses clartés

Tu tires du sein des ténèbres

D'éblouissantes vérités.

Ce voile qui des lois premières

Couvrait les augustes mystères,

Se déchire et tombe à ta voix;

Et tu suis ta route assurée,

Jusqu'à cette source sacrée

Où le monde a puisé ses lois.

Just as, long ago amid storms

On the burning peak of Sinai

The greatest of prophets

Engraved the tablets of Judah,

During the sublime encounter

A cloud covered the peak

Of the hidden mountain,

And, trembling at the thunderclaps,

Judah, prostrate in the dust,

Saw its laws come down from the skies.

So too, dispelling the false light

Of famous sophists,

You draw from the heart of darkness

Dazzling truths.

The veil that hides the august mysteries

Of the fundamental laws

Is torn and falls at your voice;

And you follow your certain path

To the sacred fountainhead

From which the world imbibed its laws.[39]

In using Mosaic imagery to aggrandize Bonald's battle against the hubristic fallacies of the Enlightenment and the Revolution, Lamartine was following Chateaubriand, who described Bonald's idol Bossuet, the seventeenth-century theologian and historian, in similar terms. "Bossuet is more than a historian," Chateaubriand wrote; "He is an . . . inspired priest, often with rays of fire on his brow, like the legislator of the Hebrews."[40]

PLATE 1.

J.-L. David, The Tennis Court Oath , Salon of 1791. Louvre, Paris

(on long-term loan to the Musée National du Château de Versailles).

PLATE 2.

Insignia of the. National Legislative Assembly, 1792.

Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

PLATE 3.

Copper-bound volume of the Constitution of 1791,

vandalized in 1793. Archives Nationales, Paris.

PLATE 4.

J.-L. David, Napoleon in His Study , 1812. National

Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Washington.

PLATE 5.

J.-B. Mauzaisse, Divine Wisdom Giving the Laws to

the Kings and Legislators, 1827. Louvre, Paris.

PLATE 6.

E. Delacroix, study for The Emperor Justinian Drafting

His Laws , 1826-27. Musée des Arts Déoratifs, Paris.

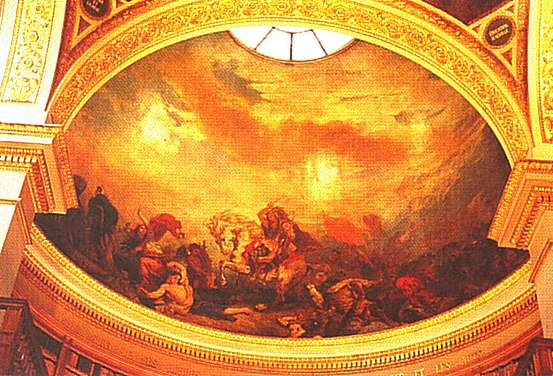

PLATE 7.

E. Delacroix, Attila, Followed by His Barbarian Hordes,

Tramples Italy and the Arts . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

PLATE 8.

E. Delacroix, Numa and Egeria . Palais-Bourbon, Paris.

PLATE 9.

J.-E Millet, Self-Portrait as Moses ,

1841 Musée Thomas Henry, Cherbourg.

Lamartine (who, like Hugo, eventually cast off his youthful ultra-royalism) later distanced himself from his poem, asserting that when he wrote it he had not read Bonald but considered him "the honest and eloquent apostle of a sublime and hazy theocracy that would serve as the poetry of our political affairs if God deigned to name his earthly viceroys and ministers." The poet confessed that "my youthful imagination was fascinated by this totally oriental and biblical doctrine."[41]

Victor Hugo used similarly political references to Moses in one of his most reactionary odes, "Le Sacre de Charles X" (1825), written in honor of the splendid neo-medieval coronation of Louis XVIII's retrograde brother. The poem concludes with a prayer that God—whom the monarch has seen face-to-face, as if on Sinai—impart to the royal brow "two rays from your head." One month before "Le Sacre de Charles X" was written, Hugo and Lamartine had received the Legion of Honor for their defense of Catholicism and monarchy. This honor was conferred at the request of Sosthène de La Rochefoucauld,[42] who would shortly serve as one of the administrators in charge of the decoration of the Council of State suite.

In light of the association of Moses with royalism and counter-revolution in the Council of State rooms and in the poetry of Lamartine and Hugo, it is surprising that liberals also appealed to the authority of the biblical legislator during the Bourbon Restoration. For example, Stendhal, after seeing a performance of Rossini's opera Mosè in Egitto in Naples in 1818, recounted how it shattered his prejudice against Scripture, which he had associated with counter-revolution:

Benedetti, in the role of Moses, appeared in a simple and sublime costume copied from the statue by Michelangelo in San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome; he had not addressed twenty words to the Eternal One before my received wisdom vanished; I no longer saw a charlatan changing his cane into a serpent . . . but a great minister of the Almighty making a vile tyrant tremble on his throne.[43]

Rossini's hero, clad in imitation of Michelangelo's revered figure (which will concern us later), revealed to Stendhal that Moses was an enemy of royal tyranny.

Joseph Salvador (1796-1873) publicly claimed Moses for the liberal cause in a controversial book of 1822. Unlike those who associated Moses with orthodoxy, obedience, and monarchy, Salvador, in Loi de Moïse, ou Système religieux et politique des Hébreux , identified him as the

author of the wisest and simplest system of public order that has ever been realized; the founder of the first known republic; the man who, having broken the chains that oppressed his people, . . . made them swear to a constitution founded on equality of rights and taught them that the law or reason must hold sway.[44]

Salvador again argued that Moses was the founder of constitutional government in his Histoire des institutions de Moïse et du peuple hébreu (1828). The liberal paper Le Globe responded enthusiastically:

There is a people more antique than Greek and Roman antiquity, whose rule of law, equality, liberty, utility, nationality, and intellectual superiority were highly acclaimed and recognized in the despotic Orient before the development of occidental civilization: the Hebrew people. The man who deserves to be considered the true founder of free and legal government . . . is Moses.[45]

What brought notoriety to Salvador's Histoire des institutions de Moïse was his claim that the condemnation of Christ had conformed to the law. Published only four years after sacrilege had been officially defined as a capital crime (a measure Bonald endorsed), the book produced an explosive reaction in the right-wing press.[46] In his Pastoral Instruction on the Progress of Impiety and on the Recent Direct Outrages toward the Person of the Savior of Man , February 2, 1829, the bishop of Chartres attacked Salvador for attempting to replace the traditional conception of Moses as the servant of God with the erroneous idea that "the famous legislator was only inspired by his genius [and by] . . . the public good." Consequently, the bishop argued, Salvador had transformed "this holy man" into "a republican more extreme than the most violent demagogues of [17]93."[47]

Salvador's politically charged view of Moses had a comic counterpart in a pair of anti-royalist Decalogue prints (c. 1827) that mimic the couplets in which the Ten Commandments were taught in the catechism. A "Constitutional Decalogue, Dedicated to the Friends of Public Liberty" prescribes fidelity to the constitutional charter (Fig. 35). A "Ministerial Decalogue," in contrast, prescribes fraud, corruption, and hypocrisy under the sign of the backward-walking crayfish, stock symbol of retrograde ultra-royalism (Fig. 36).[48] These prints—like Salvador's

Fig. 35.

"Constitutional Decalogue," c. 1827. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Fig. 36.

"Ministerial Decalogue," c. 1827. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

polemical studies of Mosaic legislation, the decorative program of the Council of State rooms, and Lamartine's ode to Bonald—speak of the broad appeal of Mosaic imagery in the ongoing crisis of authority that plagued, and eventually destroyed, the Bourbon Restoration.