Chapter 6—

Currents in Venetian Music Theory—

The Consolidation of Music and Rhetoric

As a preface to his remarks on numero, Bernardino Tomitano wrote in the Ragionamenti della lingua toscana that words made in time delight us because they are rhythmic ("numerose") and fill the soul with endearing intervals and musical proportions.[1] Tomitano went on to explain the ramifications of numero in both poetry and music. Strings, reeds, and human voices all produce number and harmony through high and low pitches that delight the ears. These in turn generate many other musical parts ("voci") by which the intervals and their proportions can combine to satisfy the listener and bring forth a more perfect sound.[2] To signify the harmonious sounding of unlike tones Tomitano depicted "[t]his loving discord or discordant lovingness" as "a most sweet procuress who, with the enticements of her sweetnesses, lures the soul into that happiness with the state of loving an unknown ['un non so che'], whom we know not well."[3] The conceit of the sweet procuress is an allegory of beauty, who charms the soul into a contentment with loving. The love thus inspired in the listener resembles the one described by Renaissance Neoplatonists, that is, a love for God as yet vaguely and dimly realized. It corresponds more precisely — if only by suggestion — to the Neoplatonic construct of earthly beauty as a seductive manifestation of the ideal proportions of the divine and of beautiful music as an aid to souls in traversing the series of emanations that lead them back to their divine origins.[4]

[1] "Le parole, che noi diciamo, fatte a tempo cotanto ci dilettano, non per altro, che perche sono numerose, & empiono l'anima nostra di amichevoli intervalli & musiche proportioni" (Tomitano, Ragionamenti della lingua toscana [Venice, 1546], p. 460). As in Chap. 5, I cite from the second edition.

[2] Ibid., p. 461.

[3] "Questa amichevole scordanza, ò discorde amicitia, è una ruffiana dolcissima, laquale con le lusinghe delle sue dolcezze tira l'anima in quel contento ad amare un non so che, che noi non bene sappiamo" (ibid.).

[4] In the next breath Tomitano acknowledges Pythagoras and Plato as his sources (ibid.). The idea relates, of course, to the notion of discordia concors, which recurs throughout medieval and Renaissance theory, but finds a particularly avid reformulation at the hands of Florentine Neoplatonists. On this idea see Claude V. Palisca, Humanism in Italian Renaissance Musical Thought (New Haven, 1985), pp. 17-21 and Chap. 8, "Harmonies and Disharmonies of the Spheres."

These proportions, Tomitano went on to explain, represent only one type of numero, however. There is another type in the measure of sound produced by human voices. This is a gauge not of pitch but of how words are properly timed and weighed to delight the soul of the listener or reader. In stressing the aural aspect of a spiritual ontology Tomitano was taking up Bembo's lead in Gli asolani, which had followed Ficino in attributing supernatural powers to sung words. As described by Lavinello in Bembo's dialogue, love displayed itself as the dual desires for beauty of the body and beauty of the soul, the one attained through sight, the other through sound.[5]

In one crucial respect Tomitano's discussion differs from those in either Gli asolani or in Bembo's Prose, namely in connecting directly sonorous aspects of verse with their translations into musical settings. One of the main reasons Tomitano exhorts poets to pay close aural attention to the verses they write is that well-timed verse makes music sweeter: "Musicians will sing beautiful and well-measured verses more sweetly and they will delight us more than when singing rough and badly composed ones."[6] This prefatory axiom grounds and justifies Tomitano's unusually detailed account of poetic sound and number as I have summarized it in the previous chapter.

Like Tomitano and other writers on language, theorists of music in midcentury Venice were trying harder and harder to forge the link between language and sound. The first notable attempt comes from the priest Giovanni del Lago, who showed a striking recognition of rhetoric's growing importance to musical developments. This is something of a surprise, for del Lago's contributions to music theory were otherwise largely unoriginal. They lay mainly in his assembling a vast collection of correspondence to which his own offerings are the least ingenious part. In fact del Lago's mind was not only derivative but almost totally speculative, since he lacked experience in composition. The real practical and theoretical consolidation of words and notes did not come until the monumental Istitutioni harmoniche of Gioseffo Zarlino, published in its first edition in 1558, which showed Zarlino as a keen observer of contemporaneous polyphonic practice. Between these two sources, with del Lago's preliminary attentions to language and Zarlino's massive speculative theories and analytical assessments of contemporary compositional practices, I attempt to reconstruct

[5] "È adunque il buono amore disiderio di bellezza tale, quale tu vedi, e d'animo parimente e di corpo, et allei, sì come a suo vero obbietto, batte e stende le sue ali per andare. Al qual volo egli due finestre ha: l'una, che a quella dell'animo lo manda, e questa è l'udire; l'altra, che a quella del corpo lo porta, e questa è il vedere. Perciò che sì come per le forme, che agli occhi si manifestano, quanta è la bellezza del corpo conosciamo, così con le voci, che gli orecchi ricevono, quanta quella dell'animo sia comprendiamo" (Pietro Bembo, Prose della volgar lingua, Gli asolani, Rime, ed. Carlo Dionisotti [Turin, 1966], p. 468). On Ficino's philosophies of magical songs see Gary Tomlinson, Music in Renaissance Magic: Toward a Historiography of Others (Chicago, 1993), Chap. 4, and for a summary of Bembo's adaptations of Ficino's theories idem, "Rinuccini, Peri, Monteverdi, and the Humanist Heritage of Opera" (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Berkeley, 1979), pp. 37-43.

[6] "[P]iu dolcemente canteranno i musici i belli & misurati versi, & piu ci diletteranno, che cantando i rozzi & mal composti" (Ragionamenti, p. 462).

an emergent consciousness of rhetorical issues in music among Venetian musicians and trace their growing confidence about how to apply them.

The Nascent Ciceronianism of Giovanni Del Lago

Del Lago was born sometime in the late fifteenth century during the heyday of courtly song.[7] His teacher, as he related in a letter of 15 September 1533, was the Paduan frottolist Giovanni Battista Zesso. By 1520 del Lago had become a priest at the tiny parish church of Santa Sofia in the Venetian sestiere of Cannaregio and had begun what was to become a copious correspondence with other music theorists. As Bonnie J. Blackburn has discerned, the addresses of various of these letters show that del Lago lodged in a series of unassuming neighborhood quarters, one near the dump by Santa Sofia, another by the barbershop there, and another presumably near the church of Santa Eufemia on the Giudecca.[8] In the course of his professional life del Lago also received mail at three different churches (Santa Sofia, Santa Eufemia, and San Martino delle Contrade in Castello), though his only lifelong association remained the tiny Santa Sofia. Even there, del Lago had to climb laboriously through the church hierarchy, where (as Blackburn has noted) he was promoted from subdeacon to deacon in 1527 and from deacon to titular priest in 1542, but never reached the highest post of curate by the time he died on 8 March 1544.

Del Lago's correspondence is preserved today in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat. lat. 5318.[9] This manuscript consists of three distinct layers. One contains primarily correspondence del Lago received from Pietro Aaron, Giovanni Spataro, Bartolomeo Tromboncino, and various minor musicians;[10] another, letters from Spataro and other theorists to Aaron (these make up layers two and three). Only one layer (the first) collects del Lago's own letters and in a most intriguing form: with one exception the items there have been transcribed by a scribe in a fair copy with the clear intention of readying them for publication. Appended to the many letters contained therein is a dedication preceded by a full title page.

[7] I am grateful to Bonnie J. Blackburn for sharing with me much information and many insights about del Lago over a number of years. The biographical notices that follow are largely indebted to her. For del Lago's collected correspondence see Bonnie J. Blackburn, Edward E. Lowinsky, and Clement A. Miller, eds., A Correspondence of Renaissance Musicians (Oxford, 1991) (here after Correspondence ).

[8] For a precise and chronological identification of these see Blackburn et al., Correspondence, Chap. 6. Much of this information is the result of Blackburn's successful foray through the church archives, which had been given up by earlier scholars.

[9] Prior to the Correspondence the most important inventories of this manuscript were those of Raffaele Casimiri, "Il codice Vatic. 5318: carteggio musicale autografo tra teorici e musici del sec. XVI dall'anno 1517 al 1543," Note d'Archivio per la Storia Musicale 16 (1939): 109-31, with an annotated chronological listing of its contents and an index of persons, and especially Knud Jeppesen, "Eine musiktheoretische Korrespondenz des früheren Cinquecento," Acta musicologica 12 (1940): 3-39, which provides information on other copies of these letters and sources of the manuscript.

[10] These include Joannes Legius, Paulo de Laurino, Pietro de Justinis, Don Laurenzio Gazio, Nicolaus Olivetus, Francesco di Pizoni, Fra Seraphim, Francesco Lupino, Hieronymo Maripietro, and Bernardino da Pavia. See the Correspondence, pp. 979-1020.

Epistole composte in lingua volgare nellequali si contiene la resulutione d'e molti reconditi dubbij della Musica: osscuramente trattati da antichi Musici, et non rettamen te intesi da Moderni a comune utilita di tutti li studiosi di tale liberale arte novamente in luce man date dal molto di cio studioso Messer Gioanne del Lago dia cono prete nella chiesa di Santa Sophia di Vinegia. Et scritte al Magnifi co Messer Girolamo Molino patricio Venetiano. (fol. [I])

Epistles composed in the vernacular language in which are contained the resolution of many recondite questions on music, obscurely treated by the ancient musicians and not fully understood by the moderns, for the common use of all the students of such liberal art, newly brought to light by the most learned Messer Giovanni del Lago deacon priest in the church of Santa Sofia of Venice. And written to the magnificent Messer Girolamo Molino, Venetian patrician.

Del Lago fashioned his title in the rhetoric of printed volumes, deploying phrases like "novamente mandate in luce" and "non più vedute" that first editions typically used to attract buyers. Other components of the title tried to pitch the contents to a wide readership, noting its use of the vernacular and the simplified explanations of complex theoretical problems that interested "studiosi" would find in it. Perhaps most notably, del Lago assembled his various explications into one of the "dialogic" forms that had just recently emerged in the era of high-volume printing, the epistolary anthology — a genre that had had its debut in print only with Pietro Aretino's Primo libro delle lettere of 1537.[11]

We have already encountered the dedicatee of these literary-styled "Epistole," Girolamo Molino, among the literary patriarchs who gathered at ca' Venier in the company of Domenico Venier, Federico Badoer, Lodovico Dolce, Girolamo Muzio, Girolamo Parabosco, and scores of other literati. Contemporary theorists such as Dolce and Bernardino Daniello listed Molino as one of the city's cardinal poets, but del Lago's dedication chronicles for the first time the nature of Molino's curiosity and skill in music.[12]

To the magnificent Mr. Girolamo Molino, Venetian patrician, most honored patron.

It is a natural instinct, magnificent sir, to desire that which one knows to be similar to oneself. Being yourself then full of virtue and celebrated among others for that, you merit not only the dedication of the present epistles in which are contained vari-

[11] On the genre as a whole, including a catalogue of epistolary collections by men and women of letters, see Amedeo Quondam, Le "carte messaggiere": retorica e modelli di comunicazione epistolare, per un indice dei libri di lettere del cinquecento (Rome, 1981). See also Margaret F. Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan: Veronica Franco, Citizen and Writer in Sixteenth-Century Venice (Chicago, 1992), Chap. 3; various essays in Writing the Female Voice: Essays on Epistolary Literature, ed. Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Boston, 1989); and on seventeenth-century France Elizabeth C. Goldsmith, Exclusive Conversations: The Art of Interaction in Seventeenth-Century France (Philadelphia, 1988).

[12] For the literary references see Chap. 4 nn. 15 and 31 and the Afterword to Chap. 4. On Molino's musical side, see Chap. 4 nn. 81-88, esp. the letter of April 1535 from Tromboncino to del Lago, cited in Chap. 4 n. 85, which sends regards to Molino.

ous questions about music, but you are to be esteemed for every other honor. And certainly one sees that few today are found (like you) gifted not only in such a science but also adorned with kindness and good morals. Therefore not finding to whom one could better submit such questions to be judged, and you being one who holds the first degree in the art of music among your other virtues, and also to show you some sign of the love and benevolence that I bear to you for infinite obligations, I make you a present. Even if it is a small gift to you (to whom much more worthy ones are due), nonetheless owing to your benign kindness it will please you to accept this little gift and it will indeed be welcome coming from one of your most faithful servants.[13]

As further confirmation of Molino's understanding of music, del Lago addressed to him a lengthy treatiselike letter, undated, giving assorted technical definitions of intervals and musical genera.[14]

It may be that Molino's patronage did not materialize into the subvention del Lago needed to publish the "Epistole"; as Blackburn notes, much of Molino's life was passed in a state of financial embarrassment owing to a family dispute over money, which he spent years fighting in court.[15] Or it may have become clear to del Lago that Molino, who kept his own works from public view, would be better honored by a gift in manuscript.

Precisely when del Lago first assembled the "Epistole" that make up layer one is not entirely clear. The fair copy was presumably made sometime between May 1535, the date of the latest letter in the "Epistole," and June 1538, that of the first letter in the following series. It seems likely that del Lago was inspired to assemble an epistolary volume only after Aretino's letters had their riveting effect on Venetian readers — that is, between 1537 and early 1538. In 1540 del Lago incorporated parts of the "Epistole"'s contents into what was to be his only published work, the treatise Breve

[13] "Al Magnifi co Messer Girolamo Molino patricio venetiano patrone Honorandissimo. É instinto naturale Magnifi co Signo re , desiderare quello, che a sé proprio si conosce simile. [Es]sendo adunque vost ra segnoria di virtu piena, et tra gli altri per cio celebrata, merita nonsolamente la dedicatione delle presenti epistole, nellequali si contengono diversi dubbij di Musica, ma esser essaltata ad'ogni altro honore. Et certo si vede che pochi, al di d'hoggi si trovano (come voi) dottata non solamente di tale scienza, ma anchora di gentilezza, et costumi ornato. Onde per non trovare à chi meglio si possino tali dubbij rimettere ad esser giudicati, et per esser voi quello, il quale nell'arte di Musica tiene il primo grado fra le altre virtute, et anchora per mostrare alcuno segno de l'amore, et benivolentia ch'io vi porto per infinite obligationi, ve ne fo uno presente, il quale anchora che sia picciol dono a' vost ra Signoria (alla quale maggior più degni si conviriano) non dimeno per vostra benigna cortesia vi piacerà, [di a]ccetare questo picciolo dono et sara poi grato venendo da uno suo fedelissimo servitore" (fol. [I']).

[14] The letter appears without date on fols. 110'-115'.

[15] For reference to this see Molino's posthumous biographer Giovan Mario Verdizzotti, in Girolamo Molino, Rime (Venice, 1573), who wrote that he was "per lo spatio di trenta & piu anni di continuo con fiera crudeltà fin al punto estremo della sua vita a gran torto travagliato, & lacerato con molti litigii, & insidie dalla malignità & perfidia di chi gli era piu congiunto di sangue" (p. [8]). Relevant archival documents are noted in Elisa Greggio, "Girolamo da Molino," Ateneo veneto, ser. 18, vol. 2, pt. 1 (1894): 194-95, and a lengthy "Difesa di se stesso al Consiglio di Dieci" survives at I-Vmc, Cod. Cic. 1099, fols. 70-92. Molino's letter to Bernardo Tasso of January 1558, partially quoted at the end of Chap. 4 above, n. 97, begins by describing the legal resolution of the battle (Delle lettere di M. Bernardo Tasso, 3 vols. [Padua, 1733-51], 2:358-59).

introduttione di musica misurata.[16] Afterward he continued to make additions and revisions to the manuscript letters, as indicated by the textual relationship of many marginal additions to them to portions of the treatise.[17] In fact, Blackburn's biographical sleuthing allows us to take del Lago's change of title from "diacono" to "prete" on the manuscript's title page as verification that he was still going about revisions in 1542 when he got his last promotion.

Originality and philological rigor fell low on del Lago's list of priorities and bore almost no relevance to the kind of publication planned for the "comune utilità di tutti li studiosi di [musica]" that he hoped to launch. Much of what found its way into the "Epistole" was cobbled together from letters del Lago had arrayed before him, some of which were actually addressed to him and others of which he had simply gotten hold. He took this miscellanea and added cribbings from any number of classical and modern sources, freely patching together each letter to form his final version. All of his writings are highly derivative as a result, as the patient philological work of Blackburn et al. now makes clearer than ever.

Despite this, the "Epistole"'s opening letter, addressed to an obscure Servite monk named Fra Seraphin and first discussed in modern times by Knud Jeppesen in 1940, commands interest as one of the earliest efforts to lay out the linguistic and grammatical principles necessary to a composer of music. Styled as a little tract, the letter occupies a sizable nine folios (fols. 2-10) complete with marginal rubrics marking the various topics. The letter is not the work of the scribe who copied the rest of the "Epistole," but an autograph. Del Lago evidently added it to the front of the corpus after the creation of layer one and affixed the date 26 August 1541, thus postdating the publication of the Breve introduttione as well as his initial assembling of the "Epistole."

Like many other letters in the "Epistole" — and in epistolary collections generally — the date is at least partly fictitious, since much of the letter had already been written much earlier. Several textual and physical factors help clarify the history of the letter's compilation. Only the initial section on the modes responds to queries by Fra Seraphin, who replied in turn on 30 April 1538.[18] In 1540 it became one of two major sections that del Lago incorporated into his Breve introduttione, the other ostensibly dealing with composing music in parts.[19] In the treatise the second of

[16] Full title: Breve introduttione di musica misurata, composta per il venerabile Pre Giovanni del Lago Venetiano: scritta al Magnifico Lorenzo Moresino patricio Venetiano patron suo honorendissimo (Venice, 1540); facs. ed. BMB, ser. 2, no. 17 (Bologna, 1969). Connections between the two are investigated in Don Harrán, "The Theorist Giovanni del Lago: A New View of the Man and His Writings," Musica disciplina 27 (1973): 107-51.

[17] See Martha Feldman, "Venice and the Madrigal in the Mid-Sixteenth Century," 2 vols. (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1987), 1:80-81.

[18] MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 74.

[19] See Harrán, "The Theorist Giovanni del Lago," pp. 121-29. The two sections appear on pp. [29]-[30] and [39]-[43] of the treatise.

these was called "Modo, & osservatione di comporre qualunche concento," but it had more to do with text setting and grammar than counterpoint.

The letter also contains two lengthy interpolations that were not part of the Breve introduttione, in addition to the minor reworkings of numerous treatise-derived sections that occur throughout. The first interpolation (on fol. 5) presents definitions of "accento, discritione, pronuntiatione, [e] modulatione." The next (on fols. 7-8') offers a grammatical summary of syllables, syllable length, the qualities of letters, and so on. Both interpolations were compiled separately from the main body of the letter: written on paper of a smaller size, the verso of the first interpolation (fol. 5') has been left entirely blank, while the end of the second interpolation is mostly blank (fol. 8), and both lack the marginal rubrics that run throughout the large-format portions of the letter. Most likely del Lago first authored all the parts in large format, probably before 1540, included them in his Breve introduttione, and subsequently inserted new sections when preparing the letter version, which he then dated 1541.[20] This hypothesis is supported by the numerous insertions of smaller passages that were added to the side and bottom margins of the original folios — glosses to the main text that qualified or enlarged on the topics at hand — all of which the printed treatise lacks.

What was the point of such a seemingly inchoate text? No easy answer suggests itself, but some clues are hidden in its clumsy structure. Immediately after his exposition of the modes, del Lago shifted without warning into an explanation of composing music for a text. "As to the observation on composing a harmony, it should be noted that every time you wish to compose a madrigal, or sonnet, or barzelletta, or other canzone, it is first necessary, searching diligently with the mind, to find a melody suited to the words . . . that is, one that suits the material."[21] This is a simple recasting of the traditional rhetorical maxim of propriety, the fitting of style to subject so often taken up by contemporaneous literary theorists. It was one voiced by medieval musicians from Guido d'Arezzo and Jacques de Liège to Franchinus Gaffurius and Martin Agricola in more recent decades.[22] Del Lago formulated it in conventional Ciceronian language by calling for an "aëre conveniente " able to match ("convenire") the "materia."[23] Unlike earlier theorists, he made no mention of Latin texts but conceived propriety in specific connection with vernacular forms. In fact

[20] Harrán, working from a copy of Vat. lat. 5318 in I-Bc, MS B. 107, 1-3, was unaware of these physical differences in the original and, therefore, of the fact that each must have been compiled at a separate time.

[21] "Quanto alla osservatione di comporre un concento primieramente è da notare, ogni volta che vorrete comporre un madrigale, o sonetto o barzeletta, o, altra canzone, prima bisogna con la mente diligentemente cercando ritrovare uno aere conveniente alle parole . . . cioè che convenga alla materia" (fol. 3; = Breve introduttione, p. [39]).

[22] See the references to these and other theorists' statements in Don Harrán, Word-Tone Relations in Musical Thought: From Antiquity to the Seventeenth Century, Musicological Studies and Documents, no. 40 (Neuhausen-Stuttgart, 1986), Appendix, Nos. 15-4-2, pp. 364-73. Many of these theorists advocate propriety in connection with modal ethos; we will see that del Lago did the same.

[23] Zarlino also consistently used forms of the verb convenire. This idea is discussed in the context of Aristotelian imitation by Walther Dürr, "Zum Verhältnis von Wort und Ton im Rhythmus des Cinquecento-Madrigals," Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 15 (1958): 89-90 and passim.

del Lago took over the preoccupation of his literary counterparts with the proper accommodation of Italian (and, by extension, secular vocal genres). By madrigale he means the sixteenth-century poetic form and adds the sonetto, the barzelletta — that lower-brow and shorter version of the ballata common in frottola settings — and other canzoni (that is, lyric poems in general). Like contemporaneous madrigalists, del Lago viewed these Italian forms as discrete and essentially poetic categories — by implication representing different poetic levels — to which appropriate musical styles would be matched.[24]

Outwardly del Lago's sudden transition from modal issues at the beginning of his letter to grammatical ones seems disjointed, but the juxtaposition may have had more to it than meets the eye. Once the reader knows the modes, he or she is then taught to make the (modal) melodies of each part fit the kinds of texts that will be set. The next passage clarifies the logic of this pedagogy. Proceeding from the explanation of the modes to the Ciceronian dictum on secular text setting cited above, del Lago returns immediately to the matter of modal properties. "Whenever learned composers have to compose a song, they are wont first to consider diligently within themselves to what end and to what purpose they create and compose it, that is, what affects of the soul they ought to move with their composition, or in what tone [or mode] they ought to compose it."[25] Not only are mode and secular music linked, but the two of them specifically with modal ethos. These linkages point suggestively toward developments in Venetian secular music of the time, which was just then starting to pay special attention to mode through modal orderings of madrigal prints.[26] The textual history behind del Lago's advice to "learned composers" sheds still more light on this question. As Claude V. Palisca discovered, del Lago lifted the passage just cited from Mattheo Nardo, probably a Florentine resident in Venice and an acquaintance of Aaron;[27] and Nardo, as it happens, was a student of Giovanni Battista Egnazio, the same humanist who taught Venier and others in Venier's circle.[28] Following the transmission of knowledge forward, a line descends in the early sixteenth century from Egnazio's schoolroom, with Nardo,

[24] On the phenomenon of identifying Italian musical genres by poetic forms in this period see the classic essay of Don Harrán, "Verse Types in the Early Madrigal," JAMS 22 (1969): 27-53.

[25] "Quante volte, che i dotti compositori hanno da comporre una cantilena, sogliono prima diligentemente fra se stessi considerare a che fine, et a che proposito quella potissimamente instituiscono, o componghino. Cioè quali affetti d'animo conquella cantilena movere debbino, cioè di qual tuono si debba comporre" (fol. 3).

[26] In the next years several prominent books would be ordered by mode: the Madrigali a cinque voci of Cipriano de Rore published in 1542, the Madrigali a cinque voci of Perissone Cambio published in 1545, and Perissone's Primo libro dei madrigali a quatro voci of 1547 (see Chaps. 8 and 9 below and Tables 6, 10, and 12). Harold S. Powers, "Tonal Types and Modal Categories in Renaissance Polyphony," JAMS 34 (1981): 428-70, speculates that there may have been a connection particular to secular music between modal ordering of prints and the general desire for what he calls "pathic and ethic effects" (p. 446).

[27] See Humanism in Italian Renaissance Musical Thought, p. 342, where Nardo's statement (preserved in I-Rvat, MS Vat. lat. 5385) appears in columns parallel to del Lago's.

[28] Palisca, arguing that Nardo's text probably preceded that of del Lago, tentatively dates it between 1522 and 1536 when Nardo's friend, Pietro Aaron, was involved (along with Egnazio) in the Aldine intellectual circle in Venice. According to his funeral oration, Egnazio was learned in music (see Palisca, ibid., p. 344 n. 30), though it seems unlikely that his learning surpassed the general knowledge that was imparted in any standard account of the seven liberal arts.

Venier, and his circle, and divides laterally to Aaron and del Lago by the late 1530s — a tantalizing crossing of musical and literary genealogies.

From this point onward, del Lago's letter sticks closely to matters of text setting, grammar, and rhetoric, all the while borrowing freely and abundantly to expand material from the Breve introduttione. In a continuation of themes bearing on modal ethos, del Lago next appears to paraphrase (unacknowledged) a passage from Sebald Heyden's De arte canendi (Nuremberg, 1540) to explain why composers ought to consider the affects of various modes.[29] "Some [modes] are happy, others pleasant, others grave and sedate, others mournful and lamenting, still others wrathful and others impetuous. And so too the melodies of the songs — one moving in one way, one in another — are variously distinguished by musicians."[30] Here del Lago sets out more clearly the Greek theory of modal ethos, which had already emerged in medieval writings on chant and was reconstituted for various discussions of Renaissance polyphony. Neither Heyden nor del Lago had a special hand in reviving the direction, of course: Gaffurius and Aaron had already made the traditional medieval juxtaposition between suiting words to music and moving the passions of the soul through various modal affects.[31] Once again, the only unique aspect of del Lago's discussion is his pointed effort to relate modal ethos to secular music.

In a somewhat later passage, del Lago extended the underlying principle of propriety, insofar as it pertains to affect, to the succession of intervals in a polyphonic composition. "Force yourself to make your harmony such that it may be happy, soft, full, sweet, resonant, grave, and fluid when sung, that is, composed of consonants in common usage, as are thirds, fourths, fifths, sixths, and octaves."[32] Even though the framework for his discussion here is propriety, del Lago tacitly assumed that proprietas was symbiotically hinged to its classical and modern twin in literary sources, varietas. Being no composer himself, he made no effort to turn the idea into a workable compositional principle but simply tossed it into the shuffle of general admonishments. Nevertheless, his naming of contrasting, even opposed, qualities ("allegro," "grave"), conceived at the level of individual intervallic progressions, indicates that local attention to variety and a belief in adapting properly the available compositional materials were beginning to spill over from literary into musical theory. Like his literary counterparts — and we will see the same to be overwhelmingly

[29] Ed. and trans. Clement A. Miller, Musicological Studies and Documents, no. 26, AIM ([Rome]; 1972), Book II, Chap. 8. The relationship between the two passages is pointed out by Blackburn et al., Correspondence, p. 877 n. 4.

[30] "[P]erche altri sono allegri, altri plausibili, altri gravi, et sedati, alcuni mesti, et gemibondi, di nuovo iracondi, altri impetuosi, così anchora le melodie de canti, perche chi in un modo, et chi in un'altro commuovono, variamente sono distinte da Musici" (fols. 3-3'; = Breve introduttione, p. [39]).

[31] Citations are given in Harrán, "The Theorist Giovanni del Lago," p. 115 nn. 32-33; see also a similar statement by Martin Agricola from his Rudimenta musices (Wittenberg, 1539), fol. D ij. Palisca provides a useful table contrasting the attributions of affect to various modes made by Aaron, Nardo, and Gaffurius in Humanism in Italian Renaissance Musical Thought, p. 345, with a comparison of the role of modal ethos in each of their writings on pp. 345-47.

[32] "Sforzatevi di far il concento vostro che sia allegro, suave, pieno d'harmonia, dolce, resonante, grave, et [a]gevole nel cantare, cioè di consonantie usitate, come sono terze, quarte, quinte, seste, et ottave" (MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 4'; = Breve introduttione, p. [40]).

true of Zarlino — del Lago pointedly confined the principle to pleasant, consonant intervals. Dissonant ones he discouraged as "mali agevoli a pronuntiar[e]," awkward to declaim.[33]

From comments relating to mode and affect, del Lago slipped into a lesson on musical and verbal cadences. However limited in understanding the subtleties of compositional procedures, he nevertheless tried here to recognize the syntactic importance of cadences, an effort in which he implied his contemporaries were often negligent.

Cadences are truly necessary and not optional, as some thoughtlessly say, especially in songs composed on words; and this is so as to distinguish between the parts of the text, that is, to make the distinctions of comma, colon, and period, so that the meaning of the complete text may be understood, both in verse and in prose — because the cadence in music is like the full stop in grammar.[34]

The distinctions of comma, colon, and period that del Lago advocated were ageold,[35] but a certain disparity of opinion over whether, or how much, contrapuntists needed to respect them had arisen once, after Josquin's time, the linear aspect of music became complicated by the vertical dimension and overlapping mechanisms of continuous, equal-voiced (or what is sometimes called "simultaneous") polyphony. In 1533 the Brescian theorist Giovanni Lanfranco had declared in his Scintille di musica that divisions of words in plainchant were made according to their meaning, whereas in polyphony such divisions were made according to the arrangement of the counterpoint and the need for rests. Only as an afterthought did Lanfranco add that even polyphonists should show some concern for verbal meaning.[36] Del Lago tried to counter such views with his insistence that cadences gauged to grammar and sense were "necessary and not optional," especially in texted music

[33] MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 4.

[34] "Le cadentie veramente sono necessarie et non arbitrarie, come alcuni inconsideratamente dicono, massimamente nel canto composto sopra le parole, et questo per distinguer le parti della oratione, cioè far la distintione del comma, et colo, et del periodo, accio che sia intesa la sententia delle parti della oratione perfetta, si nel verso, come nella prosa. perche la cadentia in musica è come il punto nella Gramatica" (MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 4; = Breve introduttione, p. [40]).

[35] For medieval and Renaissance sources voicing similar ideas see the various statements on syntax compiled in Harrán, Word-Tone Relations in Musical Thought, Appendix, Nos. 89-115, pp. 388-97. See also Palisca's brief discussion of the relationship between articulation in grammar and in music as discussed by Guido d'Arezzo and John Cotton, in Humanism in Italian Renaissance Musical Thought, pp. 338-39. Ritva Jonsson and Leo Treitler, "Medieval Music and Language: A Reconsideration of the Relationship," in Music and Language, Studies in the History of Music, vol. I (New York, 1983), pp. 1-23, clarify the importance of medieval theory in upholding such basic correspondences between grammar and music.

[36] "Or e da sapere, che le distintioni delle parole si fanno nel canto Misurato: ma non come nel Fermo: perche in questo la distintione si fa secondo la sentenza delle parole: & in quello secondo che porta l'ordine del contrapunto, & la necessita delle Pause, benche il Compositore de avertire di far la cadenza, overo distintione generale secondo la sentenza, & distintione delle parole" (Now it should be known that divisions of words are made in mensural music, but not as in plainchant, because in the latter the division is made according to the meaning of the words and in the former according to the arrangement of the counterpoint and the necessity for rests, although the composer should pay heed to making cadences or general divisions according to the meaning and division of the words); Scintille di musica (Brescia, 1533), p. 68; facs. ed. BMB, ser. 2, no. 15 (Bologna, 1970).

where words had to be made intelligible. He adduced the idea while discussing polyphony and applied it equally to settings of poetry and of prose: "Be careful then to make cadences where the parts of the text (or one of its portions) finish and not always in an identical place — because the proper place for cadences is where the thought within a group of words finishes, since it is fitting to extend and conclude together [i.e., simultaneously] the articulations of the words and notes."[37] In other words, it is the composer's duty to see that his musical composition corresponds to the grammatical structure of the texts he sets; composers should heed syntax over prosody in setting verse since syntactic settings are rhetorically clearer. His reason ("la sententia . . . delle parole"), only alluded to here, was made explicit in an earlier passage which upheld the necessity "that the meaning of the words sung be understood."[38] Del Lago's view represents a turn away from the practice of composers like his teacher Zesso and toward the proselike readings of the most recent Venetian madrigalists.

Despite del Lago's apparent lack of sophistication with polyphonic composition, not all the subtleties of a syntactically based polyphony were lost on him. Witness, for example, his discussion of "feigned cadences," roughly comparable to what Zarlino would later call "evaded cadences." "Sometimes feigning the cadence and then, at the end of it, arriving at a consonance not near to that one is commendable." This, he adds, "is intended for the soprano or another part, but the tenor in that case always makes the cadence, or division, so that the sense of the words may be understood."[39] The mechanics of del Lago's contrapuntal strategy — that when one of the cadential voices avoids the final consonance it should not be the tenor (or perhaps bass) voice — are straightforward enough. More striking is the underlying objective of clear text expression that led him to propose the idea in the first place.

[37] "Siate adunque diligente di far le cadentie, dove la parte dell'oratione, overo il membro finisce, et non sempre in un medesimo luoco, perche il luoco proprio delle cadentie è dove finisce la sententia del contesto delle parole, perche gliè cosa conveniente tendere, et parimente insieme finire la distintione, et delle parole, et delle notule" (MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 4; = Breve introduttione, p. [40]). As noted by Blackburn et al. in the Correspondence (pp. 878-79 nn. 6-7), this passage resembles one in Stefano Vanneo's Recanetum de musica aurea (Rome, 1533): "Cadentiarum denique numerus, maior quam deceat, non fiat, mira enim debet esse paucitas, nec in eodem semper loco. . . . Legitimus autem peculiarisque Cadentiarum locus est, ubi verborum contextus desinit sententia, nec immerito, decet enim et verborum et notularum distintionem pariter tendere, unaque desinere" (fol. 93'; fasc, ed. BMB, ser. 2, no. 16 [Bologna, 1969]). Harrán cites the two passages in close proximity in Word-Tone Relations in Musical Thought, pp. 391-92.

[38] "Che sia intesa la sententia delle parole cantate" (ibid., fol. 3'). Palisca (Humanism in Italian Renaissance Musical Thought, p. 341) reads the passage on fol. 4 differently, relating the phrase "non sempre in un medesmo luoco" (see n. 36 above) to Johannes Tinctoris's seventh rule of counterpoint in the Liber de arte contrapuncti stating that two cadences should not be made on the same note. But I would argue that the continuation of del Lago's passage, "perche il luoco proprio delle cadentie è dove finisce la sententia del contesto delle parole," suggests instead that del Lago is thinking of the place in the text where cadences ought to occur, not the pitches in the melody. (See also Harrán, "The Theorist Giovanni del Lago," p. 117.)

[39] "Alcuna volta finger di far cadentia, et poi nella conclusione di essa cadentia pigliare una consonantia non propinqua ad essa cadentia per accommodarsi è cosa laudabile, et questo se intende con il soprano, o altra parte, ma bisogna che sempre il tenore in questo caso, faccia egli la cadentia, o ver distintione, accio che sia intesa la sententia delle parole cantate" (MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 3'; = Breve introduttione, p. [39]). Harrán's rendering of the passage in "The Theorist Giovanni del Lago," p. 111 n. 19, based on the Bologna copy of the manuscript, is misleading.

Del Lago's grammatical digest continues with a lengthy discussion of accent under the marginal caption "Che cosa è Gramatica?" Here he tried to cover the meaning, derivation, and function of accent, the three types in Latin and Italian, respectively, and the locations of accents in Italian verse.[40] In the way typical of ancient grammars, he formulated much of his pedagogy as admonishments to avoid errors ("barbarismi" he calls them in traditional grammatical jargon).[41] In all of this del Lago was eager to demonstrate his erudition through an eclectic rehearsal of different sources; yet in amassing them to raise his prestige, he often clouded his meanings for the same readers he was trying to impress. An ironic and maddening instance of this occurs in his caveat against the "barbarismi" of setting long syllables with short notes and vice versa. "Take care not to commit barbarisms in composing notes to words; that is, do not place long accents on short syllables or short accents on long syllables, which is against the rules of grammar, without which no one can be a good musician. Grammar teaches how to declaim and write correctly."[42] Del Lago adduces the authority of the Latin grammarian Isidore of Seville to defend the rule, stating that accent has "quantità temporale."[43] Are we to infer from this that del Lago was thinking of quantitative accent and that his sources were anachronistic for the purposes of his case? Probably so, but he is characteristically vague about the precise context at hand. We will see that he subsequently attempts a discrete treatment of vernacular accent that unwittingly confuses quantitative with qualitative accent.

This notwithstanding, del Lago's most inventive contribution to music theory comes in connection with accent and text underlay as they relate to vernacular verse. The three types of final accents, he explains, include antepenultimate, which makes the sound "sdruccioloso"; ultimate, which makes it "grave"; and penultimate, which makes it "temperato."[44] This occurs in one of the few passages in which del

[40] MS Vat. lat. 5318, fols. 4'-6'; = Breve introduttione, pp. [40]-[42].

[41] See, for example: "siate cauto di non far barbarismi nel comporre le notule sopra le parole" (fol. 4', and the related statement at the end of fol. 6'); and later, "schivatevi adunque dal barbarismo il quale . . . è enuntiatione di parole corrota la letera, over il suono." On the fixation of ancient and Renaissance grammarians on avoiding errors see Keith W. Percival, "Grammar and Rhetoric in the Renaissance," in Renaissance Eloquence: Studies in the Theory and Practice of Renaissance Rhetoric, ed. James J. Murphy (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1983), pp. 324-25. For an essay that traces reactions against barbarism in sixteenth-century musical criticism see Don Harrán, "Elegance as a Concept in Sixteenth-Century Music Criticism," RQ 41 (1988): esp. 420ff.

[42] "Siate cauto di non far barbarismi nel comporre le notule sopra le parole, cioè non ponete lo accento lungo sopra le sillabe brevi, o ver l'accento breve sopra le sillabe lunghe, quia est contra regulam artis grammatices, senza la quale niuno po esser buono Musico, la quale insegna pronuntiare et scrivere drittamente" (MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 4'; = Breve introduttione, p. [40]). On this aspect of the letter see Dürr, "Zum Verhältnis von Wort und Ton," pp. 91ff.

[43] As noted by Blackburn et al., it comes from the Etymologariae, 1.32.1 (Correspondence, p. 880 n. II); originally cited by Harrán, "The Theorist Giovanni del Lago," p. 118 n. 42.

[44] "Quanto à gli accenti nel verso volgare, sono tre modi: primo, quando cade nella sillaba ante-penultima, quale rende il suono sdruccioloso; quando cade poi sopra l'ultima sillaba, rende il suono grave; et quando cade sopra la penultima, rende il suono temperato" (As to accents in vernacular verse, there are three types: first, when one falls on the antepenultimate syllable, which makes the sound slippery; then when it falls on the final syllable, making the sound grave; and when it falls on the next to last, making the sound temperate); MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 6'; = Breve introduttione, p. [41].

Lago broaches the question of affective function, and it clearly derives from current literary theory as found in Bembo's Prose della volgar lingua and in Daniello's La poetica.[45] Next he notes, after Bembo, that a line of vernacular poetry — by which he actually meant an eleven-syllable line — cannot have accents except in three syllabic positions, the fourth, sixth, or tenth:[46] lines with their accents arranged otherwise risk not being verse at all.[47] This much is clear enough, but in an unhappy conflation of his meager Latin learning with Bembo's vernacular theory, del Lago goes on to claim that "one does not place accents except on long syllables."

Ostensibly, del Lago here is still simply describing the nature of the endecasillabo in poetic terms. Yet Bembo himself had said something quite different — first, that numero has to do with the amount of time given to syllables, and second, that this is a function both of the letters that make up syllables and of the accents they receive. For Bembo vernacular accent existed a priori, and he went out of his way to make the point that the vernacular language differs from classical languages in this respect. "Speaking of accents, I do not wish to say what the Greeks do about them, more suited to their language than to ours. But I do say just this: that in each word in our language that syllable is always long on which the accents fall and all those [syllables] that precede them [are] short (emphasis mine)."[48] If del Lago really meant to tell musicians where they should place musical accents, he might have said either that musical accents must fall on accented syllables, since length in real terms could only

[45] Cf. the Prose, where Bembo says that accents should be arranged so as to fall in one of three syllabic positions: "uno di tre luoghi suole avere nelle voci, e questi sono l'ultima sillaba o la penultima o quella che sta alla penultima innanzi, con ciò sia cosa che più che tre sillabe non istanno sott'uno accento comunemente, quando si pone sopra le sillabe, che alle penultime sono precedenti, ella porge alle voci leggerezza; per ciò che . . . lievi sempre sono le due sillabe, a cui ella è dinanzi, onde la voce di necessità ne diviene sdrucciolosa. Quando cade nell'ultima sillaba, ella acquista loro peso allo 'ncontro; per ciò che giunto che all'accento è il suono, egli quivi si ferma, e come se caduto vi fosse, non se ne rileva altramente"; p. 74 in the ed. of Mario Marti (Padua, 1967). See also Bernardino Daniello, La poetica (Venice, 1536), on the three accentual types with respect to individual words: "le voci tutte o sono sdrucciolose, o comuni, o mute: (Sdrucciole quelle sono che hanno sempre nella loro innanzi penultima l'accento: Comuni quelle, che nella penultima: Mute quelle che l'hanno nell'ultima)" (p. 121); mod. ed. in Bernard Weinberg, ed., Trattati di poetica e retorica del cinquecento, 4 vols. (Bari, 1970-74), 1:308.

[46] Cf. Bembo: "a formare il verso necessariamente si richiegga che nella quarta o nella sesta o nella decima sillaba sieno sempre gli accenti" (Prose, p. 78). This idea may be compared with the exposition of accents within verse by Giovan Giorgio Trissino, La poetica, pts. 1-4 (Vicenza, 1529), fols. xix'-xx', which relates these accentual positions to the positions of caesurae (repr. in Trattati 1:62-64). See also the remarks of Daniello dealt with in Chap. 5 above, n. 121, and of Girolamo Mei on accent, summarized in Palisca, Humanism in Italian Renaissance Musical Thought, pp. 348-55, as well as the more general comments on accent in idem, Girolamo Mei (1519-1594): Letters on Ancient and Modern Music to Vincenzo Galilei and Giovanni Bardi, Musicological Studies and Documents, no. 3, AIM ([Rome], 1960; 2d ed. 1977), 117.

[47] Bembo continues: "ogni volta che qualunque s'è l'una di queste due positure non gli ha, quello non è più verso, comunque poi si stiano le altre sillabe" (Prose, p. 78).

[48] See Bembo (partially quoted in Chap. 5 n. 116, above): "Numero altro non è che il tempo che alle sillabe si dà, o lungo o brieve, ora per opera delle lettere che fanno le sillabe, ora per cagione degli accenti che si danno alle parole, e tale volta e per l'un conto e per l'altro. E prima ragionando degli accenti, dire di loro non voglio quelle cotante cose che ne dicono i Greci, più alla loro lingua richieste che alla nostra. Ma dico solamente questo, che nel nostro volgare in ciascuna voce è lunga sempre quella sillaba, a cui essi stanno sopra, e brievi tutte quelle, alle quali essi precedono" (Number is none other than the time that is given to syllables, either long or short, now because of the letters that make up the syllables, now by reason of the accents that one gives to words, and sometimes on both accounts. And, first speaking of accents . . . [here begins the passage translated in my main text]), ibid., p. 73.

have been at issue in setting Latin texts; or (better) that in setting the vernacular they should reconcile the demands of quantity — heuristically determined by vowel and consonantal weight, consonantal clusters, and the like — with those of stress.[49]

Del Lago's tendency to stray from compositional praxis was both his bane and his boon. His injunctions on "measuring" accent roved far from any practical realities of Italian verse settings; yet, taken in sum, his attentions to vernacular prosody and its rhetorical links to text setting did at least recognize some of the ways in which accent served to articulate musical rhetoric. As we saw, he thought it necessary to acknowledge the three final accentual positions in Italian verse. And in addition, he dealt in a later passage with caesurae as defined by internal accentual positions — an issue treated by several literary theorists of the time. To this end del Lago concluded his discussion of prosody by contriving a principle, unique to his writings, to govern the setting of three Italian verse types, settenario, ottonario, and endecasillabo.

Note finally this rule: that in vernacular verses of seven syllables the penultimate always receives [the accent], and in all those of eight, the third and penultimate, and in all those of eleven, the sixth and penultimate, and sometimes the fourth, but rarely both. But when it should happen to rest on the fourth, do not hold the sixth but rather the fourth and the penultimate. And this is done because of the verse and in order to avoid and escape the barbarism that can occur in composing notes to words.[50]

The final folios of del Lago's letter (fols. 7-10) cover a wide array of linguistic and metrical topics common to virtually all works on the questione della lingua and on rhetoric and poetics in the early sixteenth century. In its final form, this last section begins with the longest of the letter's interpolations, that on syllables and letters.[51] Syllables are defined by their "tenore" (accent), "spirito" (mood), "tempo" (unit of time), and "numero" (number, that is, of letters). Del Lago attributes affect only to "spirito," which may be either "aspero" (harsh) or "lene" (delicate, or sweet). Nothing is said about how syllables are made so by poets or composers, or even why composers might try to discern their affect; presumably the materials in this section were submitted as general wisdom for musicians' edification.

[49] This is much like what Thomas Campion tried to do in Elizabethan England; see my "In Defense of Campion: A New Look at His Ayres and Observations," Journal of Musicology 5 (1987): 226-56.

[50] "Notate ultimamente questa regola, che in tutti i versi volgari di sette sillabe, sempre la penultima si tiene, et in tutti quegli di otto, la terza, et la penultima, et in tutti quegli de undeci, la sesta et la penultima, et qualche volta la quarta, ma rare volte accade. Ma quando accadesse tenere la quarta, non terrete la sesta, ma la quarta et la penultima. Et questo si fa per la ragione del verso, et per schivare et fuggire il barbarismo che po accadere, componendo le notule sopra le parole" (MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 6'). Bembo makes a similar statement with respect to vernacular mertics in the Prose, pp. 77-78. See also Palisca on Mei cited in n. 46 above.

[51] See the translation in Harrán, "The Theorist Giovanni del Lago," pp. 123-24. As shown by Blackburn et al., the sources of this passage include Priscian, Bede, Sulpicius, and Diomedes (Correspondence, pp. 882-83).

Next del Lago returned to the structure of Latin verse, advising that the composer "have a knowledge of meter or verse, that is, know what a foot is and how many syllables it can have, which are long, which are short, and which are common; and know how to scan a verse and where one makes caesurae and elisions between vowels; and similarly, know where the comma, and the colon, and the period fall, both in verse and in prose."[52] He wanted to make all of these tools basic to the composer's trade and threw in the caveat that the composer must be familiar with linguistic meter and rhythm, underscoring the point (as usual) with a string of borrowed definitions.[53] Of greatest interest here again is his reiteration that such knowledge applies equally to poetry and prose.

With his usual detachment from real practice, del Lago made little serviceable use of his formidable inventories. Rather inanely he made himself out as a kind of apostle, come to proselytize the unconverted to a higher consciousness of language. His preaching probably fell on few ears, for those who would convert were engaged in more profound reconciliations of musical and linguistic phenomena than del Lago was able to reckon with. He played a role that was not proactive but reactive — not a molder of his time, but a measure of it, a gauge of the new interdependencies between language and music that were already being formed within Venetian academies and private homes. If del Lago now seems to have been incapable of formulating a coherent musical poetics, we must remind ourselves that this was never his importance among theorists or composers of his day.

Nevertheless, in the late 1530s the practical recognition of these interdependencies still lay largely outside the discourses of music theory. Aaron had adumbrated some of the issues, as revealed in Spataro's 1531 letter answering Aaron's criticisms of text setting in Spataro's Virgo prudentissimo.[54] Spataro's retort argues the conservatist party line for a kind of Absolutmusik, accusing Aaron of wanting to "take the free will from music and make it subject to grammatical accents," and chiding him for his pickiness, since neither of them was a grammarian.[55] At that point Aaron had been in Venice for about nine years, during which time he had periodically served

[52] "E necessario chel compositore habbia cognitione del metro, o, verso cioè saper che cosa è piede, et quante sillabe può havere, et quali sono lunghe, et quali sono brevi et quali sono comune. Et saper scandere il verso et dove si fa la cesura, et la collisione. Et similmente saper dove cade lo coma, et lo colo, nel periodo, si nel verso, come nella prosa" (MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 9; = Breve introduttione, p. [42]).

[53] Much of this is taken from Gaffurius, Practica musicae, who provided translations (not of his own making) of the Greeks Aristoxenus and Nichomachus (cf. MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 10'; = Breve introduttione, p. [43]). For further details see Blackburn et al., Correspondence, no. 93 nn. 39-40.

[54] MS Vat. lat. 5318, fols. 228-29'; Correspondence, no. 36, pp. 445-55.

[55] Spataro wrote, "voleti tore el libero suo arbitrio al musico et farlo subiecto a li accenti grammatici" and later, "Io non scio dove proceda che hora in le compositione de li altri andati con tanti respecti grammatici, ma credo chi bene cercasse per le vostre compositione se trovaria che non haveti havuto tanti respecti, perché la gramatica non è vostra nè mia professione."

as a courier for Willaert, fetching and delivering pieces of music.[56] In addition to his views on text setting, Aaron's writings seem to anticipate other strains in Venetian thinking that are only fully played out in Zarlino. In his Lucidario he justified his use of Italian — in reality the only language he was equipped to handle — by submitting praises of the tre corone of the trecento and a defense of Italian music and musicians.[57] Situated thus in the questione della lingua, Aaron's discussion followed directions generally set by Venetians. But he was also the first to present, in Book 2 of his Toscanello in musica,[58] a comprehensive view of simultaneous composition and triadic chords, redolent of Venetian ideals of sonority and harmony; and he showed a decided absorption with the modal questions that were to become a preoccupation of Venetian writings and musical collections soon after his Trattato della natura et cognitione di tutti gli tuoni di canto figurato appeared in 1525.[59] In recalling these incipient signs of a Venetian mindset in Aaron's writings, we should remember too that Aaron published with Venetian presses. Like Zarlino he was trying to resolve practical compositional problems for a fairly broad group of Italian readers that only the vernacular press could reach. Undoubtedly, del Lago hoped for the same, and through a much more voluminous, innovative form than he ever saw to fruition.

Ciceronianism Matured in Le Istitutioni Harmoniche of Gioseffo Zarlino

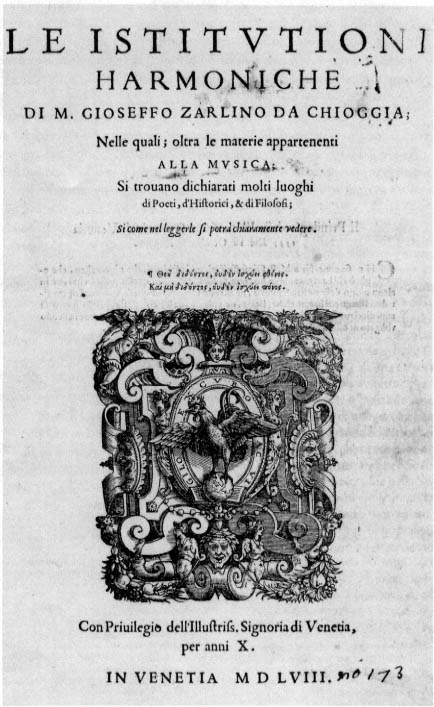

For the observer some four and a half centuries hence, Gioseffo Zarlino explains the compositional practice of Willaert and ratifies its humanistic basis more thoroughly than any other musician of the sixteenth century. Zarlino defined his mission in his first and most ambitious publication, the massive Istitutioni harmoniche of 1558. His title glossed Quintilian's encyclopedic rhetorical treatise Istitutio oratoria, which had similarly served to codify the practice of Quintilian's master and model, Cicero. The

[56] The evidence about his connections with Willaert comes from the letters of Spataro. See Peter Bergquist, "The Theoretical Writings of Pietro Aaron" (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1964), pp. 45 and passim; on Aaron's years in Venice from 1522 to 1535, see pp. 35-49.

[57] For the justification of the Italian language see the preface "a lettori" to his Lucidario in musica (Venice, 1545); fasc. ed. BMB, ser. 2, no. 12 (Bologna, 1969). Aaron's list of Italian musicians, in Book IV, Chap. 1, fols. 31-32, including "Cantori a libro," "Cantori al liuto," and "Donne a liuto et a libro," shows above all how little Italian musicians of the first decades of the century had entered the polyphonic mainstream (Costanzo Festa, Marc'Antonio Cavazzoni, Bartolomeo Tromboncino, and Marchetto Cara are the only well-known contrapuntists mentioned). The Italians' fame was instead as singers and improvisors.

[58] Title of the 2d ed. (Venice, 1529); the first ed. was called Thoscanello de la musica (Venice, 1523).

[59] Aaron wanted to regularize modes by emphasizing "regular" cadences over "irregular" ones. See the discussion in Bernhard Meier, The Modes of Classical Vocal Polyphony Described according to the Sources, trans. Ellen S. Beebe, rev. ed. (New York, 1988), Pt. 1, Chap. 4, pp. 105-6; orig. Die Tonarten der klassischen Vokalpolyphonie (Utrecht, 1974). He also connected mode to secular music, if indirectly, by specifically claiming that tenors could determine mode in any kind of composition, even those sorts unrelated to psalmody like the madrigale (Trattato della natura et cognitione di tutti gli tuoni di canto figurato [Venice, 1525]; facs. ed. BMB, ser. 2, no. 9 [Bologna, 1970], Chap. 2).

Mode figures as well in the supplement added to the 1529 edition of Toscanello. Essential on Aaron's concept of mode is the article by Harold S. Powers, "Is Mode Real? Pietro Aron, the Octenary System, and Polyphony," Basler Jahrbuch fir historische Musikpraxis 16 (1992): 9-52 (which relates Aaron's Trattato to the Venetian context on p. 20).

title page, conspicuously learned with its Greek motto, recorded his concern for musical issues pertaining to poets, historians, and philosophers (Plate 19):

The harmonic institutions of Mr. Gioseffo Zarlino of Chioggia in which, beyond materials pertaining to music, one finds explained many passages by poets, historians, and philosophers, as may be clearly seen in reading them.

Zarlino's choice of disciplines affirms his broader orientation toward the fivefold curriculum of the studia humanitatis, including poetry, history, and moral philosophy in addition to grammar and rhetoric, which were necessary to the first three. He emphasized both the practical and the philosophical — writing and thinking — and it is surely no coincidence that, like Tomitano, he opted to impart his teachings through the "reasoned" genre of treatise rather than the discursive one of dialogue. Zarlino's admission to the ranks of the short-lived Accademia Veneziana about the same time the Istitutioni were issued undoubtedly showed its founders' perception of him as a figure of wide learning, not only in music but in logic, philosophy, and ancient philology.

Despite these philosophical and encyclopedic leanings, Zarlino invoked in the proem to the Istitutioni the traditional humanistic tenet that man's superiority rests in speech: as speech was perfected and made beautiful over time, music was gradually added to it. In this way, through praises chanted to the gods, men could redeem their souls, move their wills, and reduce their appetites in order to lead a more tranquil and virtuous life. Zarlino's claim for music's power lying in its ability to persuade men to a better life with beautifully ornamented speech corresponds to that traditionally advanced by humanistic teachers.[60] As the study and practice of music eventually brought it to a separate disciplinary status from language, Zarlino continued, it fell on hard times, losing its former "veneranda gravità."[61] In modern times, however, music had found a redeemer: "The great God . . . has bestowed the grace of making Adriano Willaert born in our time, truly one of the rarest intellects who has ever practiced music, who . . . has begun to elevate our times, leading music back to that honor and dignity that it formerly had."[62] The agenda of the Istitutioni was thus to demonstrate how and why Willaert's method of composing had restored music to its ancient status.

In settling so fixedly on one composer Zarlino tacitly embraced Bembo's single-model theory of imitation as argued in De imitatione, which had largely held sway

[60] For a fundamental essay arguing the view that a belief in eloquence and the power of persuasion was the most distinctive aspect of humanistic thought see Hanna H. Gray, "Renaissance Humanism: The Pursuit of Eloquence," Journal of the History of Ideas 24 (1963): 497-514; repr. in Renaissance Essays from the Journal of the History of Ideas, ed. Paul Oskar Kristeller and Philip P. Weiner (New York, 1968), pp. 199-216.

[61] Istitutioni harmoniche, p. 1.

[62] "L'ottimo Iddio . . . ne ha conceduto gratia di far nascere a nostri tempi Adriano Vuillaert, veramente uno de più rari intelletti, che habbia la Musica prattica giamai essercitato: il quale . . . ha cominciato a levergli, & a ridurla verso quell'honore & dignità che già ella era" (ibid., pp. 1-2).

19.

Le istitutioni harmoniche (Venice, 1558), title page.

Photo courtesy of the University of Chicago, Special Collections.

in Ciceronian circles over the multiple-model theory of Pico. It is no surprise that Zarlino based his teaching on a modern-day master and not on one two centuries past, as champions of the lingua toscana had done, for even more than verbal languages, musical idioms were inextricably bound up with available technologies of composition.[63] Happily for Zarlino, his aged paragon had already been elevated to Parnassus in his own lifetime.[64]

Zarlino's Ciceronianism reached beyond the questions of technical or idiomatic imitation, however, into the deeper aesthetic crevices of his theoretical constructs. As for Bembo, beauty for Zarlino required elegance, purity, and restraint, all of which superseded other expressive demands. For this reason Zarlino issued several stern lectures to singers, cautioning them to perform only "with moderated voices, adjusted to the other singers." By singing in any other way, he warned, they would only create more "noise than harmony," and harmony could only be found by "tempering many things in such a way that no one [thing] exceeds the other."[65] For Zarlino these principles were universal. He assured singers that composers would try to outfit them with easily singable parts, organized by "beautiful, graceful, elegant movements," so that those who hear them might be "delighted rather than offended."[66] At this point in the Istitutioni he had already canonized beauty and grace in enumerating the six basic requirements of good composition: the second requirement dictated that music "be composed principally of consonances and only incidentally of a number of dissonances," and the third, that the voices "proceed properly, that is, through true and legitimate intervals born of the sonorous numbers, so that we acquire through them the use of good harmonies."[67]

The theme of avoiding offense resounds all through the Istitutioni. Some of Zarlino's famous observations on text setting seem superficially to free him from this Ciceronian straitjacket. A well-known passage (to which I will return), for instance, enjoins composers to match each word with the right musical sentiment

[63] On this issue see Howard Mayer Brown, "Emulation, Competition, and Homage: Imitation and Theories of Imitation in the Renaissance," JAMS 35 (1982): 1-48.

[64] The data presented by Creighton Gilbert, "When Did a Man in the Renaissance Grow Old?" Studies in the Renaissance 14 (1967): 7-32, indicate that by 1558, when Willaert was at least sixty-five, he would have been considered quite aged. For a summary of ways Willaert was mythologized during and after his lifetime see Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:321-24.

[65] "Ma debbe cantare con voce moderata, & proportionarla con quelle de gli altri cantori, di maniera che non superi, & non lassi udire le voci de gli altri; La onde più presto si ode strepito, che harmonia: conciosia che l'Harmonia non nasce da altro, che dalla temperatura di molte cose poste insieme in tal maniera, che l'una non superi l'altra" (Istitutioni harmoniche, p. 204). Zarlino also admonished in this chapter against excessive physical gestures by singers (ibid.), as Cicero had done for orators (Orator 17.55-18.60), with an emphasis on the impact on audience. See Hermann Zenck, "Zarlinos Istitutioni harmoniche als Quelle zur Musikanschauung der italienischen Renaissance, Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft 12 (1929-30): 577.

[66] "Cercarà . . . il Compositore di fare, che le parti della sua cantilena si possino cantar bene, & agevolmente; & che procedino con belli, leggiadri, & eleganti Movimenti; accioche gli auditori prendino diletto di tal modulationi, & non siano da veruna parte offesi" (Istitutioni harmoniche, p. 204).

[67] "La Seconda è, che sia composta principalmente di consonanze, dipoi habbia in sè per accidente molte dissonanze, collocate in essa con debiti modi. . . . La terza è, che le parti della cantilena procedino bene, cioè che le modulationi procedino per veri, & legittimi intervalli, che nascono da i numeri sonori; accioche per il mezo loro acquistiamo l'uso delle buone harmonie" (ibid., p. 172).

and to allow enough dissonance "so that when [the text] denotes harshness, hardness, cruelty, bitterness, and other similar things, the harmony may be similar to it, namely rather hard and harsh." Yet even here Zarlino continued with the caveat "but not to the degree that it would offend."[68] The expressive boundaries that had impelled Bembo some decades earlier to repudiate the "harsh, vile, and spiteful words" he perceived in Dante's Inferno were still firmly drawn.[69]

The same views led Zarlino to reject vehemently the claims of the chromaticists voiced in Nicola Vicentino's L'antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (Rome, 1555). In Part III, Chapter 80, Zarlino took passionate exception to the chromaticists' readiness to admit all the various intervals for what they professed were the oratorical ends of moving the affections. This was "most improper, for it is one thing to speak 'familiarly' and another to speak in song."[70] Nondiatonic steps, he argued, destroy modal identity — a pressing concern for contrapuntists who built their systems on the firm ground of diatonic modality.[71] In response to those who had warmed to chromatic theory he blustered, "I have never heard an orator . . . use in his speech such strange, garbled intervals as they use, and if they did I can't see how they could sway the mind of the judge and persuade him to their will, as is their goal; rather the contrary."[72] Perhaps this was Zarlino's sticking point with Rore, whose style on the whole would seem to have supported his precepts well; in any case, it is surprising that he cited — and perfunctorily at that — a mere three of Rore's works in the whole Istitutioni.

Like literary Ciceronians, for whom Bembo hovered censoriously in the background, Zarlino constantly advocated "variation" as insurance against excess. This principle grounds Part III, Chapter 29, which entreats musicians "to vary constantly the sounds, consonances, movements, and intervals," and thus "through diversity . . . attain a good and perfect harmony."[73] Zarlino's purpose in conveying these ideas is especially clear in Part III, Chapter 41, on the need to avoid parallel unisons

[68] "Debbe avertire di accompagnare . . . ogni parola, che dove ella dinoti asprezza, durezza, crudeltà, amaritudine, & altre cose simili, l'harmonia sia simile a lei, cioè alquanto dura, & aspra; di maniera però che non offendi" (ibid., p. 339).

[69] Cf. Chap. 5 below, nn. 70-71, and for the views of Tomitano, Girolamo Muzio, and Lodovico Dolce, nn. 72-76.

[70] "E grande inconveniente: imperoche altro è parlare famigliarmente; & altro è parlare modulando, o cantando" (Istitutioni harmoniche, p. 291).

[71] In addition to Zarlino's theoretical remarks see Mary S. Lewis on Zarlino's designation of the modes in the tenor part books of his 1549 book of motets, "Zarlino's Theories of Text Underlay as Illustrated in His Motet Book of 1549," Music Library Association Notes 42 (1985-86): 239-67. Zarlino's adherence to modal diatonicism should not be confused with his attitude towards modal ethos. For good reason Palisca has seen Zarlino's belief in modal ethos as half-hearted (On the Modes: Part Four of "Le Istitutioni Harmoniche," 1558, trans. Vered Cohen and ed. with an introduction by Claude V. Palisca [New Haven, 1983], p. xv).

[72] "Ne mai hò udito Oratore (poi che dicono, che bisogna imitar gli Oratori, accioche la Musica muova gli affetti) che usi nel suo parlare quelli cosi strani, & sgarbati intervalli, che usano costoro: percioche quando li usasse, non so vedere, in qual maniera potesse piegar l'animo del Giudice, & persuaderlo a fare il loro volere; si come è il suo fine; se non per il contrario" (Istitutioni harmoniche, p. 291). Cf. the passages from Cicero cited in Chap. 5 nn. 59-62, above.

[73] "[C]ercare di variar sempre li Suoni, le Consonanze, li Movimenti, & gli Intervalli; & per tal modo, dalla varietà di queste cose, verremo a fare una buona, & perfetta harmonia" (ibid., p. 177).

and octaves. Poetry, grammar, and rhetoric, he began, have all taken their cue from music, which teaches about good order and the hazards of repetition. To exemplify this in language one may consider a verse like "O fortunatam natam me consule Romam," where the reiteration of the syllables "natam," combined with the like-sounding final syllable "-mam," "give the listener little pleasure."[74] Repetition precludes beauty. "It is not permissible to use these strange modes of speech [i.e., repetition] either in prose or in poetry, except as used artificially or for special effects. The musician most particularly must eliminate from his works every unpleasant sound and whatever might offend the hearing. . . . He must regulate [his compositions] in such a way that one hears in them only good things."[75] Beauty, then, can only be grasped through the merging of elegance with diversity — that is, of decorum with variation.

Zarlino's Pedagogy of the Soggetto and Imitatione

Several of Zarlino's most insightful formulations stemmed from a desire to explain the localized contrapuntal heterogeneity that pervaded the Willaertian style of his day in terms of rhetorical varietas. Two major and interrelated instances of this play themselves out in his innovative discussions of the soggetto and of imitatione, procedures that form the aesthetic nucleus of the new style.

At its initial appearance as the first of the six requirements for good composition enumerated in Part III, Chapter 26, the soggetto corresponds simply to the rhetorical idea of materia. It is analogous to the "story or fable" of an epic poem. The soggetto in music, as in literature, may be either borrowed or invented anew. Zarlino followed Horace in advising that the soggetto should also "serve and please the listener," forming the very basis "on which the composition is founded . . . , [and] adorning it with various movements and various harmonies."[76] Up to this point the notion of the soggetto seems almost metaphorical, but when Zarlino resumes his characterization of it at the end of the chapter it becomes more concrete. A soggetto that comes from another composition may be a plainchant serving as tenor or as cantus firmus in another part, or it may be taken from canto figurato, that is, from a

[74] "[Il] Grammatico, il Rhetore, & il Poeta hanno dalla Musica questa cognitione, che la continovatione di un suono, cioè il replicare molte volte una Sillaba, o una littera istessa in una clausula di una Oratione, genera . . . Cativo parlare, o Cativa consonanza; come si ode in quel verso, O fortunatam natam me consule Romam; per il raddoppiamento della sillaba Natam, & per la terminatione del verso nella sillaba Mam, che porgono all'udito poco piacere" (ibid., p. 194).

[75] "[Repetitione] non è lecito, ne in Prosa, ne in Verso (salvo se non fusse posto cotal cosa arteficiosamente, per mostrar qualche effetto) porre questi modi strani di parlare; maggiormente il Musico debbe bandire dalle sue compositioni ogni tristo suono, & qualunque altra cosa possa offendere l'udito. . . . ma debbe regolare in tal maniera li suoi concenti, che in loro si odi ogni cosa di buono" (ibid.).

[76] Ibid., pp. 171-72.

polyphonic work. It may be placed in more than one voice and may take any number of forms, including canon.[77]

Once Zarlino begins to explain how counterpoint relates to a soggetto that is not borrowed, however, things become rather stickier. If there is no soggetto to start with, then "whatever part is first put into action or starts the composition — whatever it may be or however it may begin, low, high, or middle — that will always be the soggetto. "[78] The composer will adapt the other parts in canon (fuga ), as answers (consequenze ), or however he likes, "matching the harmonies to the words according to their content (materia )."[79] So far so good. But which part is to be understood as the soggetto in the very free method of "simultaneous" composition prevalent in Zarlino's orbit? His answer, decidedly indeterminate, begins now to touch the heart of the elusively varied style he aimed to describe.

When the composer draws the soggetto from the parts of the composition — that is, when he obtains one part from another and gets the soggetto that way, composing all the parts of the work together . . . — then that portion that is obtained from the other parts, on which he then composes the parts of the composition, will be called the soggetto. Musicians call this method "composing by fantasy"; one could also call it counterpointing [contrapuntizare ], or making counterpoint, as one likes.[80]

Here the tangibility of the soggetto threatens to vanish once again. Zarlino only clarifies the passage in Chapter 28 by stating outright, in a reversal of his earlier assertion, that the soggetto is not necessarily the first voice to sound, "but the one that observes and maintains the mode and [the one] to which the other voices are adapted, whatever their distance from the subject."[81] In the same place he refers the reader to his own seven-voice setting of the "Ave Maria" salutation from the Lord's Prayer (Ex. 3). (Zarlino included no quotations of the repertory that he cited, so it seems he expected students either to know it or, if not, to learn it.) According to his

[77] "[P]uò essere un Tenore, overo altra parte di qualunque cantilena di Canto fermo, overo di Canto figurato; overo potranno esser due, o più parti, che l'una seguiti l'altra in Fuga, o Consequenza, overo a qualunque altro modo: essendo che li varij modi di tali Soggetti sono infiniti" (ibid., p. 172).

[78] "[Q]uando non haverà ritrovato prima il Soggetto; quella parte, che sarà primieramente messa in atto; over quella con la quale il Compositore darà principio alla sua cantilena, sia qual si voglia, & incomincia a qual modo più li piace; o sia grave, overo acuta, o mezana; sempre sarà il Soggetto" (ibid.).

[79] "[A]ccommodando le harmonie alle parole, secondo che ricerca la materia contenuta in esse" (ibid.).