1

Animal Protection in Nineteenth-Century Paris The Case of Pets

During the French Revolution the problem of animal protection entered the public sphere. "At what point does the mistreatment of animals become a matter of ethics, of public concern, and should there be laws in this regard?" was the question set in a public essay contest in 1800. But not until the July Monarchy, in 1839, was an attempt made to establish an animal protection society, along British lines. The attempt failed. Nonetheless in the early 1840s more initiatives were taken to protect animals in France. In 1845, in the home of Parisot de Cassel, the seven founding members of the Société protectrice des animaux met. Male and representative of much of the upper-class political spectrum, they included Dumont de Monteux, prison doctor and self-described disciple of Rousseau; Parisot, doctor and self-described Christian; Count Renneville, a philanthropic agronomist; and Henri Blatin, Freemason, philanthropist, and republican. In 1846 the society was authorized by the government. In February 1848 it held its first annual convention, its séance solennelle, at, of all places, the Hôtel de Ville.1

Maurice Agulhon brilliantly analyzes the impact of the Revolution of 1848 on the nascent animal protection movement. Its first major success was the Grammont Law of 1850, which prohibited the public abuse of animals. The measure was negotiated through the Assemblée nationale, as Agulhon explains, by a man of the party of order, former cavalry officer and horse lover, General Grammont, with unexpected left-wing support.2 The left responded to his most telling argument—"that the spectacle of suffering encourages cruelty, that the child accustomed to bloody pastimes or witnessing cruelty will become a dangerous man, that the vicious carter (le mauvais charretier ) is latent in the child." The right had

been appalled by the bloody play in February of "a subproletariat of misérables and vagabonds." As Agulhon further explains, it was necessary to leash the mob, this "underclass" (sous-peuple, in the poet Alphonse de Lamartine's words), so easily excited by the sight of blood.3

Even before 1848, the spectacle of popular Paris had worried middle-class minds. In its request for authorization of 1846, the Société protectrice des animaux explained to the government that popular attitudes toward animals not only were an offense to public decency, they also "nurture that depth of insolence and wickedness that moves one to do wrong for the pleasure of being bad, for instance, it prompts the carter to ram other carriages just to arrest their progress, or to respond to remonstrance or entreaty with insults and threats, in short, they provoke arguments, fights, and bloody scuffles."4

The abuse of animals by provincials likewise posed a threat to Parisian public health, as the animal protection society more narrowly defined it: "The calf that the Norman carter brings to Paris is forced to travel in atrocious conditions, bound, hoof to hoof, packed in with a dozen others, thrown in the back of the cart," argued the society's bulletins in lurid detail, "may become sick (fiévreux ) and produce unwholesome meat." As Grammont more succinctly explained to the Assemblée nationale: "The poor conditions of transport of bovines . . . pose a threat to the health of consumers."[5]

Worse still were the rotting corpses of horses "in those hideous places," the knacker's yards, where the imaginative Parent-Duchâtelet saw, in horrible organic splendor, almost sublime preparations for the miasmic destruction of Paris. "There," he explained, "grow horrible masses of larvae, foul-smelling and twitching, from which emerge flies, clouds of flies that one can see spread out in the air above Paris."[6] Gratuitously, the working classes (les classes laborieuses ) weakened the economy of France. "The horse that one so abuses in Paris is a form of capital, its destruction is truly a waste," the society argued. "The massacre of horses by Parisian carters is a loss for the national economy," added Grammont.[7]

Informed by similar utilitarian ideals, doctors and other bourgeois reformers during the early years of the animal protection movement sought to impose a benign and self-consciously bourgeois model of

behavior on a ferocious working class and ignorant peasantry. A matter of social coercion, or persuasion, it is a story about a hegemonic class. But attentive readings of the later records of the Société protectrice des animaux suggest another narrative, equally drenched in the vocabulary of modernity. The haunting image of "the vicious carter" now nudges us toward metaphor.

Modernity, in this understanding, is the nebulous but given set of conditions that contemporaries experienced as material reality. Modernism is the set of aesthetic reactions to these conditions that in turn provided a cultural cast to the experience of material life. Ordinary people within bourgeois culture reshaped key images of modernity in the late Second Empire and early Third Republic. This recasting of the social imagination of the nineteenth century is apparent in changing attitudes of animal protectionism toward urban life. Initially, principles of animal protection expressed optimism about the city and were grounded in upper-class attitudes. Threats, to progress and to an orderly configuration of its signs, were located in the worker—drunken, violent, wasteful, and uncomfortably close to an unruly natural world. Urban life in itself was good—modern and bourgeois. Its problems lay in the behavior of a primitive class that education and laws might tame. But bourgeois morality soon came to embrace antipositivist themes also and in ways that illuminate our central point: by the late 1860s and 1870s the affective behavior of canines offered dramatic contrast to an increasingly cruel bourgeois and urban world, male, alienating, and relentlessly unsentimental. The pet became the countericon of the scientific, and dehumanized, age.

The dominant notes of the animal protection movement sounded forth in the context of the modern city, of Haussmann's Paris, and seemed to afford triumphant expressions of class superiority. In 1855 the Grand Exposition was the particular setting for the society's work, broadly conceived as injecting a healthful dose of morality into an otherwise beneficent materialism. Paris during the exposition was a stunning panorama of industry and genius, society members proudly remarked: "the rendezvous of nations, it presents to [our] dazzled eyes . . . innumerable products of work and genius from every latitude." The rebuilding of Paris was dazzling in itself. "In the new splendor of

its streets and its activities, Paris appears as the most magnificent of spectacles," the society reported in its bulletin. The organizers of the Société protectrice des animaux were worthy of modernity's challenge. "In the midst of so many wonders," marveled the organization's president in an address to members, "is it not also noble and moving to see dedicated people like yourselves," he added, "meeting to assure protection to the weak and to strengthen that moral sense without which all the material works of civilization," he asserted with passion, "are only useless baubles."[8]

Two years later lower-class brutality toward animals still marred Paris, the reports of the society, confirmed, in ways that strengthened the early organization's dominant themes: working-class attitudes and behavior—waste and violence—threatened the impressive bearing of progress. Describing Paris and the goals of the animal protection society, the reports took an exultant and self-congratulatory tone despite accounts of continued violence. "If we have not completely reached our goals," suggested the secretary general of the society, "at least we may congratulate ourselves on improvements effected in this beautiful capital of France," where, he insisted too hopefully, "the most revolting cruelties no longer occur." The society firmly situated its civilizing goals in positivistic terms, "having its headquarters," its members tellingly explained, "in the capital of civilization itself."[9]

Women had a part in the movement: they were to bolster these positivistic goals. In 1855 the society's president outlined the relation of women to animal protection. Speaking to the organization's annual convention, he explained that the support of women, of women of social position, that is, would be a "precious support." "A cause entrusted to women is a cause won," he gallantly explained. Other leaders of the society stressed the logical connection between women's interests and animal protection. "The cause of animal protection, that is, the protection of the weak against the strong, of moral and intellectual force substituted for brute physical power, in short, of civilization . . . cannot fail to interest the ladies," the secretary, general explained.[10]

Sentiment was women's forte in the society's predictable reading of gender. Feeling needed constraint, however, if it was not to slip into sentimentality and interfere with the work of protection. "We have no sympathy for those irrational passions that inspire people weakened by

age or otherwise subject to blind caprice. . .. We are looking for generous hearts that are guided by lofty intelligence," he told the assembly, feeling sure, he said pointedly, that his meaning was clear.[11]

Women's role in animal protection throughout the 1850s and 1860s was decorative, symbolic, and marginal. It was represented at annual conventions that figuratively expressed the concerns of the society. Next to richly dressed ladies sat notables from the worlds of science, arts and letters, and government; scattered among the assembly were prize-winning peasants, distinctive in their blouses. By the early 1860s dames patronesses —women whose social position and contributions to the society were especially noteworthy—were grouped on stage, in the places of honor. Occasionally they read poetry. In 1861 the assembly enthusiastically applauded Madame Ségalas, whose verses, "The Devil in Paris," sadly, as the minutes to the meeting explain, contained nothing particularly relevant to the work of animal protection.[12]

Complacent assumptions of male superiority were shaken in a series of debates on vivisection in the 1860s and 1870s that opposed affect to effect. The former, tautological, relation of the modem to the good was dislodged: in an unstable doubling back on itself the notion of danger traveled figuratively from the irrational classes—women and workers—to rest uneasily on the modernizers and on their city itself as well.

Prompted by a study at the Academic de médecine on the merits of regulating vivisection, the Société protectrice des animaux formed a committee in 1860 to examine the problem of vivisection.[13] The committee's arguments set the tone for a discussion of rationality that encouraged the participation of a wider public. In principle, vivisection was good. It was scientific; it was beneficial. Insofar as it was useful, vivisection could not be cruel. A safely positivistic definition of abuse was proposed. "To merit approval, vivisections must be strictly kept within the limits of their noble goal," the committee warned, "they must only be the means of verifying a hypothesis that has been well defined in advance." The suffering of the subject must be limited to that which "is absolutely indispensable" to the experiment. "Beyond that begins cruelty, since there also begins the gratuitous, the absence of utility."[14]

Many Sociétaires (members), however, questioned whether vivisection could ever be useful. As early as the 1850s critics drew attention to notorious examples of excessive experimentation to show its ineffec-

tiveness.[15] "To attach an animal to an operating table, to plunge a lancet into its palpitating flesh, to dissect it alive, to make its blood pour out, to elicit its cries or howls of pain, of rage, or of fright, to incite its anger or stupefy it with terror," such acts could hardly serve any useful purpose, argued Doctor Roche, for instance, member of the Académie de méde-cine and vice-president of the Société protectrice des animaux.[16]

Victor Meunier, animal protection society member and editor of Ami des sciences, one of the first illustrated reviews of science aimed at a general audience, pointed out that vivisectors themselves sometimes admitted the futility of their work. In a description of a typically horrible experiment on dogs, "here in his own words," Meunier reported, "is how [the vivisector] explained his work to the Société médicale des hôpitaux: 'Hollow probes would not work so iron rods were inserted . . . the dogs had to be gassed, muzzled, and hog-tied, then left without food or water for three days, conditions that are not those of rational experimentation'—the scientist concluded—'they remove all meaning from the experiments."' How, Meunier exclaimed to his audience, can you believe your ears; "it is the author of the experiments himself who declares that they have no meaning . . . that they are not performed under reasonable conditions!" Why then were these experiments performed, Meunier asks? Surely a physiologist knows what he is doing: "he knew it . . . and he did it!"[17]

As other members fumbled for answers to Meunier's rhetorical demand, the emphasis of the problem shifted from the occasional if notorious excesses of vivisection to the corrupting influence of modernity itself. One member argued that "in the old days" the great men of physiology, "the Harveys, the Asellis, the Pecquets, and the Hailers, had never had the idea of making use of vivisections the way we do today." Vivisection then, didactic historians of animal protection proclaimed, was practiced only in order "to come to some great and useful discovery." Vivisectors worked "far from the public, helped by only one or two assistants." They were deeply moved by their experiments and perhaps even "had a painful memory" of them. Haller, especially: "One knows, indeed, that . . . the famous physiologist of the eighteenth century often voiced the remorse he felt with respect to the many animals he had dissected alive, toward the goal of illuminating his scientific research."

But in modern times, as the secretary of the Académie de médecine explained, "we have a completely different spectacle."[18]

Vivisection was new and its practices were horrifying. "A word that carries with it a frightful meaning, vivisection, is a modern creation," some critics wrongly believed.[19] Modern experiments on animals were publicly, repeatedly, and crassly performed, others more reasonably observed. At the auditorium of the country's most important institution of higher learning, the Collège de France, one observer noted that experiments were completely unlike the almost reverential ones of the previous century: "There, milling around excitedly were demonstrators, assistants, the simply curious, and even students."[20] The thirst for knowledge there was often little more than idle curiosity.[21] "It is to an auditorium filled . . . with loafers coming to warm themselves in winter and to sleep during the summer, that the professor ministering to a banal curiosity performs these horrible interludes of blood more disgusting than the banquets of Atreus [who served up to Thyestes the flesh of his own children]," in the emphatic words of the Sociétaire who wrote. A Sa Majesté l'Empereur des Français: Humble supplique du caniche Médor, a pamphlet presented from the pet's point of view.[22]

Perverted scientific reasoning led to false values. "One would think that scientists were looking for an excuse to torture animals," noted the head of the Ecole nationale vétérinaire (school of veterinary medicine) at Maisons-Alfort, "if one did not realize that their conduct is a consequence of their way of reasoning." In an attempt to circumvent the imagination and its supposed pitfalls, "one applies oneself to inventing mechanical methods [of performing research]. The physiologist transforms himself into a machine that computes, that weighs and measures; he tries to work out with his hands those problems that can be resolved only by the mind." Many otherwise respectable people, he also noted, "make no distinction between chopping a piece of wood and flaying a live animal; for the most futile motives, they martyr that animal, starve it to death, in exactly the same way as we would redo an arithmetic problem, to see the error made in adding several figures."[23]

Some antivivisectionists attacked positivist science head-on: "Many scientists are convinced that there is nothing useful in science except what they call facts." In the mind of such a critic, "In the factual sciences . . . to

say that a phenomenon exists without proving so is equivalent to saying nothing." Otherwise learned doctors were swept away by a fetishism of facts. A Doctor Guardia explained in the prestigious newspaper Le Temps that the claims of the tormentors of animals were the "deplorable consequences of this rigid experimental method, applied too rigorously to the organic sciences by minds lacking initiative and weight," prompted by the unfortunate desire, he suggested, "to make physiology and medicine conform to its model."[24]

The experimental method when applied to physiology exposed the evil in human beings. It made them cruel: "The habit of experimenting [on animals] makes some individuals so indifferent to the pain they cause," explained Dr. Carteaux, "that as a result one finds them thrusting their lancet deeply into the tissues [of an animal] and leaving it there, unthinkingly, in order to enter into a discussion that, certainly, could have been held easily at another time." Contempt for feeling was institutionalized in the training of scientists where sense was privileged at the expense of sensibility, in an enseignement scientifique that never included training in the field of feeling.[25]

Ambition was also to blame for the horrors of vivisection, ambition fueling the competition among its practitioners, as members of the society imagined. No sooner did news of an apparent discovery leak out from a leading laboratory then other scientists, "envious of or allied with one another," the president of the Société protectrice des animaux explained, "race to torture other animals, here, out of jealous rivalry, in order to contest the supposed discovery, there, out of the spirit of camaraderie, to uphold the discovery and exploit it in turn."[26]

The same point about scientific ambition and its role in the abuse of animals was more dramatically made by a Doctor Joulin: "If remorse is not an empty word . . . what dame macabre of mutilated animals must prance in rage on the breasts of scientists!" But no, he concluded: "Remorse is not made for winners, and each of them sleeps . . . with the sweet conviction that his discoveries will make him the equal of Harvey and will permit the human race to close the great book of science."[27]

The tensions between hope for positive bourgeois knowledge and revulsion for scientific method were brilliantly embodied in the vivisector's most frequent victim, the dog. In it, in a recursive movement,

the themes of bourgeois modernity and working-class behavior disturbingly united. Other animals were of course subject to experimentation: frogs, guinea pigs, rabbits, the occasional cat, and in the veterinary schools for training purposes, horses. Dogs, however, were cheap, docile, easy to obtain, and present in the minds of the bourgeoisie.[28]

The crux of the issue was a sacrifice of virtue. Arranged around the dog were attributes that had little to do with scientific values. The selfless affection of the dog set off the extreme egoism of the scientific search for discovery; its helpless canine devotion framed the disturbing, even sexual, thrust of science. In the complaint of Amadée Latour, editor in chief of the Union médicale: "Why this preference on the part of experimenters for inoffensive animals like the dog? I will never forgive the sacrifice of that animal. It is abominable that an animal so loyal and so loving is subjected to the knife and the tongs. . .. What you do, and the way you do it, is abominable and immoral," he insisted. A refreshing understatement of the problem appeared in the 1860 bulletin of the Société protectrice des animaux. It developed the same contrast of higher canine worth, of sentiment, in a cruel scientific world: "These unending tortures, cruelly inflicted upon sweet and submissive animals, upon poor beings as defenseless as they are speechless, these are not, for many of us, the most legitimate of actions."[29] Or, as Dr. Carteaux, Sociétaire, helped his audience of fellow members to imagine, when, after multiple experiments, the subject was brought back for more operations, "it is not unusual, if it is a dog, to see him, anxiously, fearfully submissive, drag himself half-mutilated back up onto the torture table all the while trying to touch the hearts of his tormenters with caresses and pleading looks."[30]

The most telling icon of positivist cruelty for antivivisectonists was the image of the dog victim appealing for mercy. British audiences in the 1880s would be outraged by a typically French scene of a dog begging for mercy. Dogs brought up from the cellar to Claude Bernard's laboratory, a speaker would explain, "seemed seized with horror as soon as they smelt the air of the place, divining, apparently, their approaching fate. They would make friendly advances to each of the three or four persons present, and as far as eyes, ears and tails could make a mute appeal for mercy eloquent, they tried in vain."[31]

The path to a devaluation of positivism was paved by the recognition that the "madness of French physiology," as some critics called it, marked by gratuitous violence, sexuality, and waste of life, was uncomfortably close to the impulses of working-class culture. The vivisector too was driven by base needs. He had a passion to destroy and a love of gain, marked by an uncivilized disregard for pain. As Victor Meunier, in his article in Ami des sciences, wondered: "The strikes of the knife by the vivisector, are they less blameworthy than the blows of the carter?" Either the mutilation of animals is a wrong, or it is not a wrong, another critic insisted. "One cannot deplore too bitterly the suffering inflicted on horses by drivers or owners motivated by greed," he explained, but with respect to vivisection, "the one practice leads to prison and a fine while the other leads to the Institute [of France, which includes the Académie des sciences] and to riches."[32] In another powerful image, the vivisector was also a thief, "stealing neighborhood dogs and cats in order to amuse himself at what he calls experiments or operations on those poor dogs."[33]

Like le mauvais charretier but paradoxically more dangerous because they were modern, vivisectors now stood as a threat to bourgeois values. Self-assurance was undercut when representative figures of bourgeois rationality were exposed, didactically, as occasionally bloodthirsty, cruel and potentially beastly echoes of the working class. Vivisection undermined bourgeois and haut-bourgeois values, just as surely as did working-class politics. It underlined the weakness of their overall position, the absence of absolutes that might bolster their own sense of class.

Mentally, this shift from optimism implied a corresponding distancing from the scientific nature of the debate on vivisection. It was not just medical men who worried about the collapse of morality and class. Indeed the marquess of Montcalm, the society's vice-president in 1860, stressed the power of ordinary people's views. "In speaking before you on the subject of vivisection, I do not feel restrained in the least by my complete lack of medical knowledge," he admitted. Distanced from any professional concerns, he could speak on behalf of other, ordinary, fellow members. "I can say then that I am going to deal with this subject not only in spite of not being a doctor, but even and especially because of not being a doctor," he explained.[34] In a lighter but similar vein, Cham of the satirical newspaper Le Charivari asked in a public letter why one could

not, "in the interest of science, perform these same operations on those gentlemen—the vivisectionists—whose internal organization must, fortunately for humanity, differ completely from that of other men."[35]

By the end of the 1860s the silence of the Académie de médecine on the proper procedures for vivisection dampened professional men's enthusiasm for discussion of the subject. Interest in vivisection was kept alive in the 1870s by female members of the Société protectrice des animaux, who articulated the widespread discontent with its principles and practice. The comtesse de Noailles (an older relative of the poet), for instance, donated 1,500 francs for an essay contest on the pros and cons of vivisection. The widow of Henri Blatin also succeeded in stimulating discussion of the issue. After twenty years of silently following the debates of the animal protection society, in 1878 nine years after the death of her husband she was moved to a cri du coeur against vivisection. The society had proposed a moderate stance on vivisection to be taken at an impending international conference on animal protection. "The protectors of animals," the widow said in response, "must not accept any situation detrimental to their protégés. Leave the plea of extenuating circumstances to others than their protectors," she added, in obvious criticism of the official position on vivisection. Mme Blatin and another member, a M. Decroix, pointedly described as a single man, exchanged words on the subject. Decroix claimed (correctly) that Henri Blatin had approved of vivisection in principle if it were regulated. Mine Blarin insisted that her husband had been always and completely against vivisection. The minutes suggest a contentious meeting.[36]

In the 1880s antivivisectionist societies, with prominent and distinguished female members, were briefly fashionable.[37] La Société française contre la vivisection, for instance, was founded in 1882 with support from the comtesse de Noailles. It prided itself on its honorary president, Victor Hugo, who commented that "Vivisection is a crime." Although Hugo's level of engagement in the antivivisection society was less than complete, throughout the fin de siècle the organization continued to attract supporters among the literati, including Aurélien Scholl, Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, and Léon Daudet. Unlike its offshoots in the Belle Epoque that drifted into radical vegetarianism and seemingly ludicrous revelarions—such as that vivisection leads to cannibalism—the Société

française contre la vivisection remained, tenuously, within the paradigm of official science.[38]

More confrontational was the Ligue populaire contre les abus de la vivisection directed by Marie Huot (less well known as an active member of the Parisian animal protection society) and Mafia Deraismes; this group explicitly joined antivivisection with women's concerns. In a speech sponsored in 1883 by the Ligue populaire, Deraismes reiterated objections to vivisection voiced within the Société protectrice des animaux in the 1860s. In her speech against vivisection, Deraismes argued that vivisection was useless and that scientists were prompted by "an unhealthy curiosity." She added, "They are intoxicated by the blood they spill, drunk on the suffering they produce."[39]

In a departure from conventional animal protectionist tropes, Deraismes probed the consequences of the devaluation of sentiment that was distinctive of science, of modern male scientists, she emphasized: "One of the most striking characteristics of the man who calls himself a scientist is his great disdain for feeling." In the principle that held that the end justifies the means, Deraismes foresaw the perversions of eugenics. She warned: "In the human race, as in all others, alongside an elite there exist pariahs, outcasts, in a word, misfits, crazies, and criminals. Why would not science dispose of them? Nothing, really, differentiates them from animals. They are only poorly organized matter and consequently harmful despite the fact that they are human. An intelligent animal is infinitely more precious than they."[40]

Marie Huot, a member of the Société protectrice des animaux's standing committee on the dog pound in the late 1870s, became secretary of the Ligue populaire contre les abus de la vivisection; from this position she dramatically joined battle with male science. She attacked Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard (after Claude Bernard and Paul Bert, one of the most well known vivisectionists), beating him with an umbrella while he was operating at the Collège de France on a live monkey. Later she spit at a statue of Claude Bernard during its inauguration ceremony not, she claimed, out of particular malice toward Bernard, "but because they had felt the need to place an eviscerated dog at his side."[41]

More quietly around 1880, in response to antivivisectionist appeals, women began to set up and run private refuges for persecuted animals.

The fashionable journal La Vie contemporaine recalled the campaign against vivisection during this less fervent decade: "The ladies occupied themselves with rescuing dogs and cats, spending all their small resources on the creation of animal shelters."[42] Individual rescue efforts that the animal protection society had financed in the mid-1870s included those of Mme Lamargo, rue de l'Evêque, who, the society learned, rescued and cared for abandoned dogs, and Mme Graye, rue Feutrier, a seller of offal who, a society member told its prize committee, "has become the salvation of the stray dogs of her neighborhood."[43] Alain Corbin's research on smells suggests the success of these measures. Between 1810 and 1820 Parisians complained about cowsheds in the city. In the 1850s it was pigs that offended. From 1859 onward the smell of animals in general grew troublesome, and in the 1880s, Corbin writes, "one hears complaints of the odor emanating from dog hospitals."[44]

A significant network of feminine patronage existed throughout the 1870s and 1880s for the rescue of lost dogs, extending from rich bourgeoises like Mile Fanny Bernard or Mme d'Este Davenport, "who spends the major part of her fortune on animals," to the so-called dog and cat ladies of Paris who used their meager, occasionally supplemented, income to buy bread for the homeless animals in their neighborhood.[45]

Nineteenth-century animal rescue was for many women an escape from a dangerous and masculine scientific world. The case of Claude Bernard's daughter illustrates the collision of feminine sensibility with these troublesome norms that parallels the history of antipositivism in Paris. We are told in a surely apocryphal story of Fanny Bernard's abrupt disenchantment with her scientist father. As the story goes, one day Fanny's best friend comes to her in despair. My dog has disappeared, she cries. Fanny tells her not to worry. Papa will know what to do. The two girls run to the Collège de France. A foolish attendant lets them into the vivisection chamber where Claude Bernard is working. We guess the rest of the story: Bernard is caught in the process of cutting up alive the friend's dog.[46]

Fanny Bernard's experience was traumatizing, of course. She lay sick in bed for weeks afterwards. Later in her life, one contemporary asserted, "It appears that the idea of expiation moved her and that in redemption for the suffering formerly imposed by the great physiologist on the

animals he studied, she determined to bring happiness to those specimens of the same species that fall into her hands."[47]

Bernard's charity supported a number of private refuges and pensions for dogs in Paris. She paid an allowance to Mile Mazerolles, for example, who lived on the rue de Buci and took care of old and sick cats. Mile Bernard herself succored some eighty dogs at her retreat at Bezons-la-Garenne.[48] In her work of expiation for her father's sins—the funding and establishment of canine refuges in and around Paris—the focus shifted, significantly, from animals in the hands of scientists to dogs lost in the city. The prism of her life and work with refuges came to overshadow the issue of vivisection itself. In protectionist praxis in general the image of a dangerous city came to predominate. Virginie Déjazet, the actress, was well known for her habit of rescuing stray dogs. Her obituary in Le Figaro in 1875 described her habitually stooping to pick up dirty and wet dogs in the street.[49]

At the end of the century Valentin Magnan, psychiatrist and physiologist, described how one déclassée antivivisectionist spent her time: "She collects all the stray dogs she finds in the streets, taking them home with her or placing them in another shelter. She has made a will in favor of five or six of them she cares for at home. She has left each 25 francs a month but, fearing that sum is insufficient, she has decided to increase it." Clinically Magnan accumulated details: "Scarcely in the street and her work of protection begins. She picks up pieces of glass and other sharp objects, for fear that a horse might, in falling, cut itself on them, increasing its pain. One day she spent, she," Magnan repeated, "in her fine lady's dress, more than a half-hour in this ragpicker's work."[50]

In France as in Britain, the antivivisection movement seems to have been fueled by women's keen identification with helpless animals who lived at the mercy of controlling scientists.[51] Theodore Zeldin notes, "It was said that women led the movement against cruelty to animals as a consolation for the brutality they endured from men."[52] Claude Bernard himself, in Coral Lansbury's reading of his Introduction à l'étude de la médecine expérimentale, "described nature as a woman who must be forced to unveil herself when she is attacked by the experimenter, who must be put to the question and subdued."[53] In feminist discourse in general, "la science masculine" came to be posed against "les malheu-reuses femmes" as in the later work of Cleyre Yvelin who argued in

1910 that vivisection would end when women were allowed into the Académie de médecie.[54]

In the shift from triumphant modernity to modernism women had an increasingly important part. They were involved in the day-to-day work of the Société protectrice des animaux, work whose central goal was the definition of class. Second, and more interesting, the ideas associated with women pushed against the limits of bourgeois ideology. Sentiment, once imprisoned within the private sphere, came during the work of protection to settle in the public sites of bourgeois life.

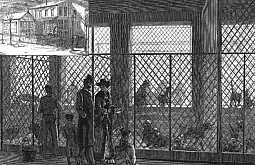

For men and women alike, the qualities of pets—vulnerability and sensitivity, qualities long identified with femininity—broadly contrasted with the nature of urban life and undercut the city's positivistic intent. Throughout the 1870s members of the Parisian animal protection society such as Mile Lilla Pichard, M. Charbonnier, and Mme de Channel demanded the establishment of a home for lost dogs, "reiterate[d] the view, so often aired among us, that a refuge for lost or abandoned dogs be founded."[55] In 1885, the society did found a refuge at Arcueil (figure r), but it soon closed for lack of funds.[56]

Individual Sociétaires occasionally rescued dogs. M. Hadamer, for instance, announced proudly at the June 1876 monthly meeting that he was rescuing dogs from the streets, dogs that if sent to the dog pound, the Fourrière, "would be hung without delay." Less anecdotal was the contribution of Dr. Bourrel, whose dog hospital on the rue Fontaineau-Roi was also an unofficial animal shelter. The society was continually sending homeless dogs to him. A typical request resolved in this way was that of one member, M. Montanger, who asked the society in 1874 "if some member of the society would agree to adopt [a blind dog] whose masters have just died. The concierge of the house where the animal lived took him in temporarily but the owner has forbidden her to keep him any longer."[57]

Private refuges were an alternative to the Parisian pound, "the morgue for things" in the evocative phrase of a Revue Britannique author. Established in 1811 as "a depository for things and animals taken from the public thoroughfares," by the middle of the nineteenth century the Fourrière was functioning inadequately as a dog pound. Dogs were abused, neither fed nor watered before, finally, being hung.[58] They might be sold to vivisectionists. "It is better for the dogs to be hung

Figure 1. The refuge of the Société protectrice des animaux at Arcueil. Collection Roget-Viollet.

rather than be released to medical students who would use them for vivisection experiments and subject them, therefore, to prolonged agony," as one corresponding member of the animal protection society argued in 1873, voicing common neighborhood fears that behind closed doors medical students were experimenting viciously on animals.[59]

The sounds of the Fourrière, of dogs slowly dying from blows or asphyxiation or hanging, mingled in Parisian minds with the equally chilling howls of the victims of vivisection. As a Doctor Condier complained in a letter to the Société protectrice des animaux about the Parisian dog pound, "not only are these unfortunate [dogs] hung there, but they are beat on the head with a stick, which makes them cry horribly to the great disgust of the neighbors."[60]

The aural imagery presented in a much publicized court case on vivisection in 1879 between the city of Paris and a Mme Gélyot, owner of a lodging house on the rue de la Sorbonne, gives a more vivid description of how animal pain, real or imagined, affected and unnerved neighborhood life. Mme Gélyot sued the government for damages

caused to her business by Paul Bert's vivisection laboratory, which was located across the street at the Sorbonne. Tenants moved out because the sounds of dogs crying in the night disturbed their sleep. An officer carefully collected evidence that supported Mine Gélyot's case. "He had even taken the trouble to distinguish between the various types of howls that he heard when he went to the rue de la Sorbonne," it was explained. One dog, he reported, "barked in a deep mode," another "in a sharp, high-pitched mode," and a third, most pathetically, "wailed in tones that resembled a human voice." Gélyot's bourgeois, petit-bourgeois, and artisan neighbors supported her suit and testified to the disturbing character of the problem. M. Charlotte, an attorney, claimed that "several times in the night he had rushed out of bed believing that someone was being murdered in the street."[61]

Anxiety invested in a hostile city now overlapped the enduring tensions of class in animal protection discourse for pet owner and antivivisectionist alike. Bourgeois rescuers continued to save animals from hard-hearted workers.[62] But what emerges clearly is the contribution by the animal protection movement in its varying gendered modes to a redefinition of public life. In the early years of the Société protectrice des animaux, in the late 1840s and 1850s, the organizing image of danger for bourgeois and haut-bourgeois reformers was "the vicious carter." The behavior and beliefs of working-class people were to blame, Parisians believed, for the nastiness of modern life, for its violent nature. The goal of animal protection initially was the reshaping of popular Paris to fit the norms of Haussmannization—utility, predictability, and controllability. By 1880, however, its goals and claims were far less secure. Parsed, the working classes and the upper classes were disturbingly alike, marked by masculine violence. And Pads, long the site of class distinctions, was the home of new and discomforting uncertainties. Dichotomies on which the understanding of modernity had rested—good-bad, bourgeois-working class, civilization-nature, male-female—became harder to maintain without a readjustment of the modernist imagination. The image of the evil scientist appeared alongside the construct of the pet. AS the next chapters will show us, the ostensible emptiness of bourgeois life was filled by suprahuman, loving, and faithful pets, on an equally fictional plane.