Structure of the Blood Vessels

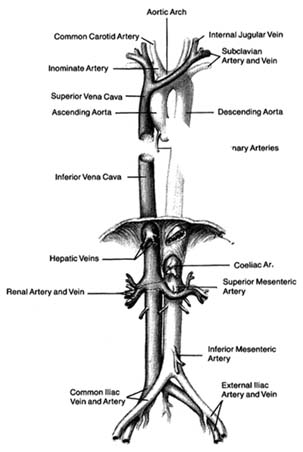

The greater circulation consists of the aorta, the arteries, the arterioles, the capillary network, and the veins. The aorta, after arising from the left ventricle, sends off two coronary arteries and then runs upward (as the ascending aorta ), arches to the left (aortic arch ), and turns downward (descending aorta), in front of the spinal column, until it reaches the lower abdomen, where it divides into two principal branches. (The aorta and its more important branches are shown in figure 6.) The coronary arteries supply the heart itself; the aorta supplies blood to the head and upper extremities by means of four major arteries: two carotid arteries and two subclavian arteries . On the right side the carotid and subclavian originate as a joint, short trunk (innominate artery ); on the left side they arise directly from the aorta. The aorta sends off no major branches until it passes below the diaphragm, where three major arteries originate from its frontal wall, and two from its side wall, supplying all abdominal organs. The branches of the coeliac artery supply the stomach, liver, spleen, and pancreas. The renal artery supplies the kidneys, and the iliac artery carries blood to the lower trunk and the legs. The mesentric artery supplies the intestines.

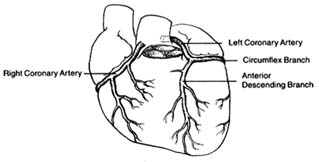

The coronary arteries provide the blood supply for the heart itself (fig. 7). The left coronary artery runs a very short course and then divides into two large branches, the anterior descending coronary artery and the left circumflex coronary artery . The former supplies the front of the heart, particularly the left ventricle; the latter supplies the lower left portion, the back of the left ventricle, and the left atrium. The right coronary artery runs a moderately long course before dividing into branches; it supplies the right side of the heart and the lower back portion of the left ventricle. Even

Figure 6. The principal arteries and veins. The heart has been removed from the illustration. Only initial portions of smaller vessels are shown.

though only two arteries originate from the aorta, the two branches of the left coronary artery are counted as major vessels; thus the clinician is used to thinking in terms of three, rather than two, sources of arterial blood supply to the heart.

The arteries in the body divide and subdivide into smaller segments. The smallest arterial branches, at the borderline of visibility, are called arterioles , beyond which the blood enters a myriad of

Figure 7. The coronary arterial circulation.

microscopic channels with very thin walls, the capillaries . These minute blood vessels are located within the tissues and organs of the body; they are integral parts of the various organ structures. The capillaries join together into very small veins, or venules , which in turn join together into increasingly large veins, eventually forming the two major veins, the superior and inferior vena cava. Larger veins usually accompany corresponding arteries and carry the same names, as indicated in figure 6. The inferior vena cava, the principal lower vein, is located alongside the aorta, deriving tributary veins similar to branches of the aorta. It drains blood from the abdomen and the lower part of the body into the right atrium. The large upper vein, the superior vena cava, drains blood from the head and upper extremities through four tributary veins analogous to the four corresponding arterial branches. It runs a short course in the chest, entering the upper portion of the right atrium.

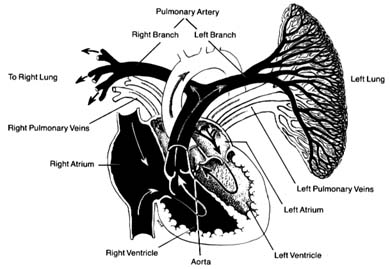

The pulmonary circulation is presented in figure 8. Venous (dark) blood collected in the right atrium is pumped by the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery, which, after a short course upward, divides into two principal branches, each supplying one lung. The right and left branches of the pulmonary artery are large vessels, frequently referred to as the "right pulmonary artery" and "left pulmonary artery," in which case the pulmonary artery is called the "pulmonary trunk." Each artery divides into as many branches as there are lobes of the lungs (three on the right side and two on the left). These branches subdivide further into smaller and smaller branches, forming pulmonary arterioles and then pulmonary capillaries. The capillaries collect into venules and veins,

Figure 8. The pulmonary circulation. The right lung has been removed

from the drawing. Oxygenated blood is shown in

white and deoxygenated blood in black.

through which fully oxygenated blood returns to the left side of the heart. Four large veins, two from each lung, carry the blood to the left atrium.

The blood vessels show important structural differences, related to their various functions. The aorta and the largest of the arteries act as collectors and receptacles of blood; hence they are thick-walled and elastic. Smaller arteries participate in regulating blood flow and may require contraction and relaxation under certain conditions; hence their tissues are less elastic and more muscular. The arterioles have a particularly well-developed musculature; its contraction and relaxation is the principal factor in regulating blood pressure, as will be discussed later (chap. 3). The walls of the pulmonary artery are thinner than those of the aorta, as it is exposed to considerably lower pressure. Smaller pulmonary arteries and arterioles have poorly developed musculature, although in certain diseases this muscular tissue develops. The veins of the systemic and the pulmonary circuits are thin-walled, collapsible vessels in which blood flows under low pressure. Larger systemic veins have valves (similar to the semilunar valves of the heart) that prevent backflow

of blood, particularly in parts of the body where blood flows against gravity.

The lymphatic system is an auxiliary system of blood vessels carrying a white tissue fluid (lymph ) resembling blood plasma that participates in the nutritional process of organs. Most tissues of the body contain lymphatic capillaries, which collect certain elements of tissue fluid and carry it through a fine network into larger vessels and then into a large duct (thoracic duct ) that runs upward along the thoracic spine and empties itself into a tributary of the superior vena cava. The lymph thus mixes with blood and becomes part of the blood plasma. Smaller lymphatic vessels are connected with lymph nodes, which act as important filters, extracting undesirable components of tissue fluid and preventing them from entering the bloodstream.