Stalin's Soviet Legacy

The collapse of the Romanov dynasty touched off a vigorous anti-urban revolt among many intellectuals, particularly in the small community of professional urbanists and architects. At least among professional circles, this revulsion against the urban environment was centered in Moscow, where living conditions were every bit as pestilential as in Petrograd,[32] but where the city's physical unruliness offered none of the psychic relief provided by the lingering orderly aesthetic impact of the still-visible Alexandrine physical plant in Petrograd. In Petrograd, revulsion against the city's abysmal living conditions took a slightly different turn.[33]

As in Moscow, local Petrograd officials moved immediately to clean up particularly noxious neighborhoods.[34] Nevertheless, the local architectural community's image of the city remained essentially the original Romanov vision as transmitted through the prism of the "New Urbanism" of the city's turn-of-the-century artistic intelligentsia. The continued nurturing of this tradition by Leningrad architects throughout the 1920s psychologically prepared that community for Lazar Kaganovich's 1931 declaration that the Soviet Union's industrial future would be urban by definition.[35]

Immediately after Kaganovich's 1931 address, central elites instructed the city governments and Communist Party organizations in Moscow and Leningrad to prepare comprehensive physical development plans for their cities. In 1935 the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) and the USSR Council of People's Commissars joined with Moscow municipal institutions to promulgate a comprehensive plan for the reconstruction of Moscow.[36] The following year the same central institutions joined with the Leningrad city soviet to enact an equally far-reaching general development plan for the old imperial northern capital.[37]

According to the 1936 Leningrad general plan drawn up under the direction of Lev Il'in and Vladimir Vitman, the city would abandon its historic center focused on the Admiralty and Neva for a new and grander city center along an expansive boulevard (International [now Moskovskii] Prospekt) running directly south from the Peace Square for some ten kilometers (see Map 7).[38] This new city center, which together with the buildings of the 1920s has recently become a hub of historic preservation efforts,[39] was unified through a common focus on

Map 7.

International/Moscow Prospekt project.

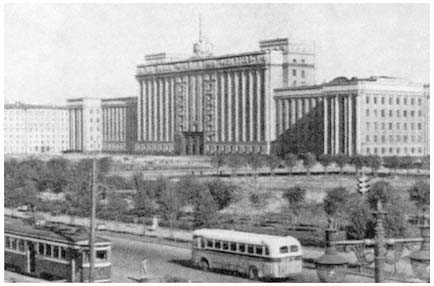

Figure 12.

House of Soviets building.

a gargantuan House of Soviets building placed strategically along the new thoroughfare.[40] That whole complex, when constructed, covered a total of 13 acres, nine of which were deemed to be usable building space.[41] Heavy and neoclassical, this ponderous building overwhelmed the as-yet vacant surrounding territory. The House of Soviets, and the 1936 general plan that produced it, captured not only the ethos of Stalinist statism but also that of the "New Petersburg" movement of three decades earlier (see Figure 12). This project represented the logical culmination of an imperial Petersburg tradition that sought to symbolize the pomposity of state authority in stone. Its neoclassical inspiration similarly testifies that the arrogant assertion of human order over nature, visible in the classicism of the Renaissance, continued to inspire imperial Russian and Soviet architects centuries later.

In his memoirs, Nikolai Baranov attests to the direct influence of Renaissance design principles and philosophy on his generation of Leningrad architects as they set to work during the Stalinist period.[42] Baranov, who was the city's chief architect from 1938 until 1950 and was one of the most influential Soviet city planners of his era,[43] reports that Lev Il'in, his predecessor as chief architect from 1925 until 1938, served as a primary mentor to the city's numerous young architects throughout the twenties and thirties (Il'in was later killed during a German bombardment of the city in December 1942).[44] Il'in, it turns out, collected eighteenth- and nineteenth-century furniture, paintings, carpets, china, and crystal.[45] He also compiled a 5,000-volume library of rare archi-

tectural works focusing primarily on the period of the Italian Renaissance, including works by Palladio, Alberti, and Piranesi.[46]

Il'in's chosen visual environment was that of Renaissance classicism and Russian neoclassicism. Through his thoughtful supervision of their work, he transmitted his aesthetic preferences to a generation of apprentice architects. Similarly, his own designs for Leningrad, as well as for Baku, where he also served as chief architect throughout most of the 1930s, displayed an intense interest in neoclassical principles.[47] Confronted with the strong neoclassical tradition of Leningrad and of its professional architectural elite, the new-found statism of the Stalinist regime saw in Peter's former capital a ready outlet for its pretensions.

Soon, however, Leningrad city administrators came to view the initial 1936 general plan as impractical. In 1938, a team of architects under Baranov and Aleksandr Naumov revised the original plan, seeking a more effective use of the available land.[48] As part of this revision, the new city center project was scaled down from 99 acres to 28. Baranov later observed that this reduction brought the planned ensemble into scale with such urban vistas as the Mall in Washington, D.C., and the Champs-Elysées in Paris.[49] The new plan also noted that "serious inconveniences" would result from an immediate abandonment of the historic city center. Nevertheless, the primary thrust of new construction was still concentrated in the same four districts first designed in 1936: Avtovo, Shchemilovka, Malaia Okhta, and the International Prospekt Project (see Map 8).[50] From 1936 until 1941 more than 800,000 square meters of housing space, 213 schools, and 200 preschool facilities were built in the city, mainly in these four areas.[51]

Three overarching considerations explain the plan's preoccupation with moving the city's population southward. First, the new center was designed to overwhelm the historic city core, thereby destroying the political symbolism of the prerevolutionary architectural ensemble by erecting an even grander "socialist" statist environment nearby. Second, by moving the city to higher ground, the planners sought to reduce a tragic pattern of flooding. Third, once the decision was made to abandon the historic city center, movement to the south became inevitable. With the Finnish border only 22 miles to the north, national security interests demanded urban development in the opposite direction. The short but bloody Winter War with the Finns in 1939–1940 demonstrated the military wisdom of such a plan, as Leningrad was quickly transformed into a garrison city. Of the 200,000 Soviet casualties suffered in that war, by far the largest percentage were among Leningraders.[52] This loss was, of course, soon overshadowed by the virtual annihilation that occurred during World War II's blockade.

On the night of June 21–22, 1941, Hitler's Wehrmacht rolled across the Soviet Union's western frontier, and within a few weeks the

Map 8.

Major construction projects during the 1930s.

Map 9.

The front line on September 25, 1941.

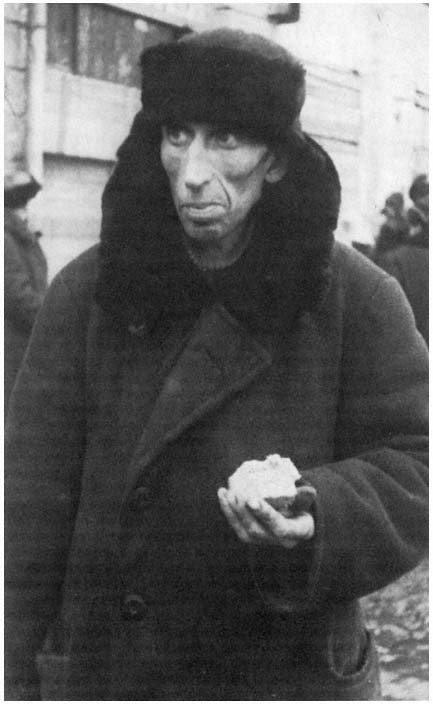

Figure 13.

Photo of effects of the blockade.

country's second largest city was under a siege that was to last two and a half years (see Map 9 and Figure 13).[53] The fate of over 40 percent of the city's prewar population is unknown and cannot be reconstructed from official Soviet statistics.[54] What is known is that, by early 1942, Leningrad's population had been cut by two thirds through war-related casualties, starvation (as many as 30,000 civilians died on each of the worst February days), and evacuation (over a half-million civilians successfully left the city on the 237-mile "Road of Life" across the ice of Lake Ladoga and through surrounding forests to the nearest railhead).[55] To put these figures into comparative perspective, the number of Leningraders who perished during the blockade approximately equals the total number of U.S. armed forces personnel who died in all wars from the American Revolution through the war in Vietnam.[56] By the end of the blockade's second winter, Leningrad had shrunk to only 639,000 residents—less than the city's population at the height of the Civil War—and its industrial base was operating at only 10 percent of its prewar capacity when measured by the value of industrial production.[57]