Three

Safety Standards for Grain Elevators

Private regulation is often characterized as weak or diluted, a kind of lowest common denominator of prevailing business practices. Many private standards are considered largely defensive, motivated by the desire to forestall government regulation. Public standards, by contrast, are thought to be more stringent than their private counterparts, sometimes unreasonably so. Public regulation is also considered inordinately cumbersome, laden with procedural requirements and judicial appeals.

These conceptions of public and private regulation are borne out substantially in the case of grain elevator safety. The private standard (NFPA 61B) is generally lax, reflecting industry's desire to avoid meaningful regulation of dust-control practices. The public sector, on the other hand, developed a more demanding standard but spent almost ten years in the process. The Office of Management and Budget shares the conclusion of the National Grain and Feed Association (NGFA) that the OSHA regulation is burdensome and unreasonable. As with so many regulatory issues, however, the relevant data are weak and inconclusive. Proponents and critics advance plausible, but divergent, arguments, each as good as its unsure assumptions. OSHA's grain elevator standard, for reasons argued below, actually seems worthwhile. It fills the gap in existing practices and is likely to produce benefits in excess of costs.

The importance of this case is twofold. First, it contributes to the conventional wisdom by providing specific details about actual behav-

ior and suggesting ways in which this behavior is affected by institutional design and external influences. Two popular explanations of public regulation—"capture" theory and Bernstein's "life-cycle" theory—have been discredited for their incompleteness. The "life cycle" is a vivid metaphor, but it lacks causal content about the force and nature of the regulatory "aging" process.[1] Similarly, capture theory has been challenged by the rise in social regulation, where government actions are opposed, not favored, by the regulated.[2] This case study illuminates several aspects of the conventional wisdom about public and private standards. For example, the enforcement ethic in the public sector tempered OSHA's willingness to adjust the regulatory burden on certain low-risk facilities.

Second, this case highlights an aspect of NFPA's behavior that does not fit the conventional image of private regulation. Several provisions in NFPA 61B are surprisingly strict. When judged by the criteria used to evaluate public regulation, a few NFPA provisions appear to be unreasonable. This suggests a previously unrecognized aspect of private regulatory behavior. Private standards-setting is not all "lowest common denominator" politics. There is a mixture of managerial behavior (marked by considerations of politics and economics) and technical behavior (permeated by the ethos of engineers). Managerial considerations explain the biggest weakness in NFPA 61B: favoring one regulatory approach to dust hazards (ignition control) to the complete exclusion of another technique (dust control). But some realms of private decisionmaking are dominated by technical, more than managerial, influences. The "technical" provisions in NFPA 61B are the most stringent. Technical influences help explain why NFPA 61B was developed more than fifty years before OSHA considered writing a standard. This case indicates how professional engineers alter the dynamics of private regulatory decisionmaking. These influences are sketched in greater detail in later chapters; but first the story of public and private efforts to regulate grain elevator safety.

Grain Elevators and the Explosion Problem

Grain elevators come in all sizes and shapes. Some are connected to processing facilities, others serve only as bulk storage. Bulk storage facilities are often grouped into three functional categories that roughly correlate with their size: country elevators (the smallest), inland terminals, and export terminals (the largest).[3] Differences in function, prod-

uct, and capacity have all been urged as reasons for avoiding safety standards of general application. Feed mills, for example, have a much better safety record than bulk grain storage facilities.[4] Some "country elevators" handle grain only a few days a year, obviously minimizing the opportunities for accidents. The significance of these distinctions for safety regulation is unclear because throughput—the amount of grain moved through a facility—has a more direct bearing on safety than function or capacity.[5]

The Explosion Problem

Of all the hazards associated with grain handling, the most serious one is also the most difficult for those outside the grain business to understand. It is grain dust. This dust, generated whenever grain is handled, is easier to ignite and results in a more severe explosion than equal quantities of TNT. One insurance company distributes placards with the warning "Grain dust is like high explosives." Dust explosions account for the vast majority of personal injuries and property losses in grain-handling facilities. There are thousands of small fires in these facilities every year; estimates range from 2,970 to 11,000. But the twenty to thirty explosions a year account for almost 80 percent of the property damage and 95 percent of the fatalities[6] (see table 4). Making sense of these trends over time is complicated by the changing fortunes of the grain trade. The major explosions in 1977–78 coincided with tremendous increases in wheat exports (primarily to the Soviet Union). The comparatively low number of explosions in recent years, on the other hand, is attributable in part to decreases in grain sales.[7] Fluctuations in trade patterns notwithstanding, the explosion problem remains the most serious hazard in grain elevators.

Contrary to popular belief, explosions in grain elevators are not caused by spontaneous combustion. To cause an explosion, the dust must be mixed with air to form a dense cloud. (Layered dust only smolders upon ignition.) The airborne dust concentrations must also be above the lower explosive limit (LEL), a condition so opaque that visibility is minimal and breathing is difficult. Concentrations above the LEL occur regularly inside most bucket elevators (described below) but seldom elsewhere in a facility. Also contrary to popular belief, grain elevator explosions are not one big blast. They usually involve a primary explosion and a series of secondary ones.[8] The primary explosion generates shock waves throughout the elevator, often raising into sus-

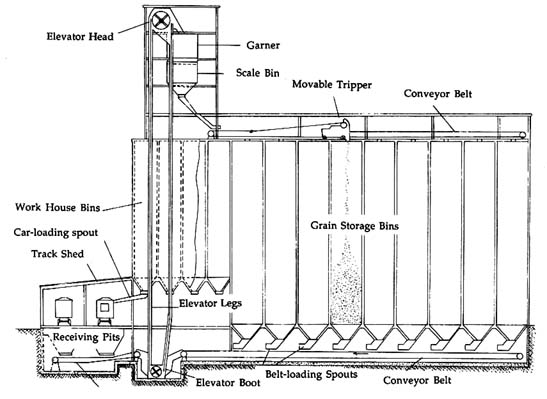

Figure 1. Terminal-Type Grain Elevator

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

pension layered dust on walls, rafters, equipment, and the floor. Accumulations of as little as one-hundredth of an inch will propagate the flame from an initial explosion. In other words, layered dust provides the fuel to turn a primary explosion—often itself quite minor—into a major one.

There are two basic schools of thought about how to approach the explosion hazard: one, eliminate ignition sources; two, control airborne and layered dust. Although it seems obvious that neither strategy should be pursued exclusively, the debate over safety standards is often between groups that have a strong preference for one approach.

The Ignition-Control Strategy

Industry's inclination, according to a former USDA investigator, is to concentrate on ignition sources. Ignition occurs most frequently in the bucket elevator—a continuous conveyor belt with equally spaced buckets (often metal) that elevates the grain and discharges it into a spout (see figure 1). The top section of a bucket elevator, where the drive is

located, is referred to as the "head." The bottom section, where grain enters the elevator, is known as the "boot." The "leg" connects the head and the boot.

Ignition sources are varied and often notoriously difficult to pinpoint. In a study of fourteen explosions, the USDA identified ten different "probable sources," the largest group (four) being "unknown."[9] Most studies agree that welding or cutting (also known as "hot work") is the largest known ignition source, accounting for perhaps 10 to 20 percent of all explosions. Other common ignition sources include electrical failure, overheated bearings, foreign metal objects sparking inside the leg, and friction in choked legs. "Jogging the leg"—trying to free a jammed bucket conveyor by repeatedly stopping and starting the driving motor—is a primary cause of friction-induced explosions.

Ignition-source control can take several forms. One is mechanical. Mechanisms including electromagnets and special grates can minimize the problem of metal objects entering the grain stream. Belt speed, alignment, and heat monitors can be used to detect hazardous conditions and shut down the equipment before suspended dust is ignited. The effectiveness of these devices varies, but quality has improved since their introduction to the grain-handling industry ten or fifteen years ago. Another approach to ignition control is behavioral. Employees are instructed not to jog the legs. Rules against smoking are strictly enforced. Permit procedures are instituted to ensure that hot work is done safely, and preventative maintenance schedules are instituted and implemented.

Whatever the combination of mechanical and behavioral requirements, ignition-source control has two limitations. First, there are countless potential ignition sources. The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) has reported the results of two surveys in which the ignition source remained unknown in over half the cases. Virtually every piece of equipment, as well as every grain transfer point, is a potential ignition source. Eliminating or controlling them all seems impossible. Second, as an NAS panelist put it, "ignition control is fine if you have perfect people; but people will make mistakes and then the equipment fails." A common example is jogging jammed conveyors instead of inspecting and digging out the elevator boot. This problem has been recognized for years, yet it persists largely unabated. According to an insurance representative, operators of some country elevators encourage this time-saving but risky practice. In short, everyone agrees that good operating procedures are a good idea. They are also inherently

difficult to enforce. Since operational breakdowns are inevitable, critics consider this loss control method inadequate by itself.

The Housekeeping Strategy

The other school of thought about grain elevator safety is enamored of—some say preoccupied with—"housekeeping" (or dust control). The label can be misleading to the extent that it conjures up only images of brooms and vacuum cleaners. Dust control is aimed at both airborne and layered dust. Airborne dust can be removed by various systems of aspiration, also called pneumatic ("moved or worked by air pressure)" dust control. Pneumatic dust-control systems have four major components: hoods or other enclosures; ductwork; a filter, or dust collector; and an exhaust fan. Layered dust can also be removed automatically, but in all but the largest facilities it is removed manually: with vacuum cleaners, brooms, compressed air, and, in some cases, water.

Both types of housekeeping (pneumatic dust control and layered dust removal) are controversial, but in the first case the disagreement is mostly technical, while in the second it is largely a matter of economics. The technical potential of pneumatic dust control is highly disputed. One grain elevator insurance company touts a system it claims can reduce dust concentrations in the bucket elevator below the lower explosive limit. The technology was not proven to the satisfaction of a 1982 NAS panel, but panel members placed a high priority on continued research in this area.[10] Many in the industry still consider such technology unavailable. Others claim to have used it successfully.[11] Both are probably right, as the design of pneumatic dust-control systems is, according to a Cargill engineer, "more of an art than a science." Engineers cannot simply take specifications for the desired concentration of airborne dust (or rate of accumulation for layered dust) and design a system that will perform accordingly. The technology for removing airborne dust is too uncertain. Much depends on how the system is installed and maintained.

Layered dust poses much less of a technical problem. How to remove it effectively is not very controversial (although the virtues of vacuuming versus sweeping are a minor topic of disagreement). For large facilities, dust removal is usually part of normal operations. Sweeping is done at least once per shift at all export facilities. But for many smaller facilities, removing layered dust means hiring additional labor and slowing down operations when they are most profitable. Few quarrel

with the conclusion of the NAS that housekeeping and maintenance are often given low priority and are usually the first tasks postponed when there is a rush of business.[12] A grain company representative on the NFPA Technical Committee on Agricultural Dusts concurs that "there are many, many filthy ones that get by." A less tactful USDA investigator describes the prevailing levels of housekeeping in grain elevators as "fair to abysmal." The main objections to stricter housekeeping rules is the cost. The controversy, in short, is managerial, not technical.

Trying to estimate the number of "bad apples" is difficult, however. "It depends on which day of the week you are counting," as one industry representative put it. There has been very little counting to date. No one even knows with precision how many elevators there are, let alone when they were all built and what kind of equipment they currently use. Harder still is determining the relative cleanliness or safety levels of grain-handling facilities. No industry group investigates or collects information on explosions. NFPA collects statistics through newspaper clippings and voluntary reporting from the fire service, but this information is hardly comprehensive. A USDA task force concluded that the NFPA estimate of annual fires in grain elevators may understate the actual situation by a factor of five.[13]

The NFPA Standard for Grain Elevators

Whatever the numbers, insurance companies have worried about grain elevators since a series of big explosions in 1919 and 1921. Responding to calls for an industrywide standard on grain elevator safety, NFPA appointed a Committee on Dust Control in Grain Elevators. Insurance interests have been major participants in NFPA's subsequent efforts. The committee, lacking sufficient information on certain aspects of the explosion problem, hired Underwriters Labs (another organization created by the insurance industry) to investigate methods of controlling floating dust in terminal grain elevators.

The results of the UL study formed the basis for the dust-control provisions in the early versions of the standard, which also contains general operation and design provisions. It has been revised at least five times since then, although many of the provisions in the most recent version can be traced back to 1953. The most significant changes were in 1970, when NFPA added country elevators (formerly governed by a separate standard) to the scope of the standard, and in 1980, when NFPA responded to the threat of imminent government regulation by strengthening the ignition-control requirements for bucket elevators.

The revision process began again with a meeting in July 1985 of the Technical Committee on Agricultural Dusts, and a revised version of NFPA 61B (hereinafter "61B") was adopted the following year.

The Agricultural Dusts committee, chaired for the past fifteen years by a representative of Continental Grain, has approximately two dozen members. Twelve to fifteen attend formal committee meetings, but all actions are subject to letter ballot by the full committee. The largest-segment of committee membership comes from the insurance industry—Industrial Risk Insurers, the Mill Mutuals, the Insurance Services Office of Nebraska, Kemper Insurance Co., and Factory Mutual Research Corp. are each represented. Two other organizations related to the insurance industry, UL and Johnson & Higgins (a brokerage firm), are represented on the committee along with Cargill, the country's largest grain company, and two major grain processors (Kellogg Co. and General Foods). Other representatives include those of a fumigant company, a fire equipment manufacturer, a manufacturer of grain-handling equipment, and several academics. Conspicuously absent from the committee roster is a representative from OSHA. "It wasn't for lack of trying," notes an NFPA staff member. Neither was it always this way. OSHA's policy on participating in private standards-setting activities has varied by administration and by issue.

Certain provisions in 61B have been a source of repeated debate over the years. Such issues, according to the current committee chairman, are brought up practically every time 61B is revised. Some of these largely technical issues are discussed below. But 61B is probably better known for what it does not cover than for what it does. Some provisions, including those on housekeeping, are so general that the standard quite literally requires nothing in particular. Additionally, owing to the retroactivity clause, most provisions apply only to new facilities, even though older facilities actually pose the most serious hazards.[14]

In its present form, 61B is a remarkably compact regulation, devoting no more than a page or two apiece to chapters on construction requirements, equipment, and dust control. Most provisions are as general as they are brief. "Extraneous material that would contribute to a fire hazard shall be removed from the commodity before it enters the [grain] dryer."[15] "Boot sections [of the elevator leg] shall be provided with adequate doors for cleanout of the entire boot and for inspection of the boot pulley and leg belt."[16]

NFPA 61B avoids almost all design details. The complex topic of

explosion venting, for example, is addressed by reference to a separate NFPA venting guide that committee members agree is not particularly applicable to grain-handling facilities.[17] Similarly, dust-control systems are mentioned, but there are no performance requirements or construction specifications.[18] In contrast, the National Academy of Sciences has published a 116-page guide to designing pneumatic dust-control systems.

Housekeeping: A Gentlemen's Agreement

The most significant provision in 61B is the basic housekeeping requirement. Unlike the standard later adopted by OSHA, which contains specific action levels and alternatives for dust control, 61B dispenses with the topic by stating simply that "dust shall be removed concurrently with operations."[19] This language has been known to provoke a good laugh from Agricultural Dusts committee members pressed to explain what it really means.

Whatever it means, the provision is not enforceable. OSHA learned that when it tried to use 61B in support of citations issued after the 1977 explosions. The commission that reviews OSHA citations was unwilling to rely on such an ambiguous provisions.[20] In actuality, the housekeeping provision is not a "requirement" at all. It is more of a gentlemen's agreement to recognize the problem but leave its solution entirely to the individual operator. "I think that you have to consider that people are going to be reasonable and rational about applying this," explained a Continental Grain representative at an OSHA hearing.[21]

Whether a more specific requirement would be desirable is the subject of considerable controversy. Leaving that question aside for the moment, the lack of specificity of the housekeeping requirement in 61B is not adequately justified by the reasons most commonly offered in its defense. "If someone can tell us how to be more specific and be scientifically logical" in establishing dust-control requirements, explains an Agricultural Dusts committee member from a major grain company, "we would buy it." Indeed, there is no way to do so—short of banning grain dust—if "scientific logic" demands total safety. Research sponsored by the NGFA indicates that a dust layer as thin as one-hundredth of an inch can propagate an explosion. The NGFA has been accused by its detractors of conducting this research precisely to bolster the "scientific" argument against any standard. But there rarely is a strong

scientific basis for resolving complex problems involving the trade-off between cost and safety. If this call for greater scientific certainty applied equally to all standards-setting, it would largely paralyze the effort. There are too many variables interacting and changing over time to expect anything resembling scientific certainty for each one.

Guesses, commonsense judgments, and just plain arbitrary numbers adorn public and private standards alike. They have to. NFPA 61B is no exception. The requirement that grain driers be cleaned every 168 hours, for example, is not scientifically logical. As it turns out, 168 was chosen because that is how many hours there are in a week—a measure no more scientific than Continental Grain's policy of cleaning them every 48 hours.[22] Limiting the temperature of hot pipes to 160° F, prohibiting more than 25 percent of a roof from being plastic panel, and suggesting that motor-driven equipment be cleaned at one-hour intervals during operations are further examples of provisions in 61B that are equally susceptible to the charge of scientific infirmity.[23] In each case, the number is an admittedly arbitrary one, based on the consensus of committee members as to what constitutes a reasonable requirement.

In fact, scientific uncertainty did not prevent Continental Grain or the Factory Mutual Corporation from incorporating an "action level" of one-eight of an inch of layered dust into their own in-house standards for housekeeping.[24] So why does the NFPA Agricultural Dusts committee demand more of science? One possible reason is that the dust-control problem is more complicated than most issues. Hot pipes present similar hazards under a variety of circumstances; grain dust does not. Dust hazards depend, to some degree, on virtually every aspect of a grain-handling facility, including the product it handles, its sales and operation patterns, the general layout and date of design, and the effectiveness of existing dust-control equipment. In short, some facilities have much less need or ability than others to conduct housekeeping. The image of the "small country elevator"—a mom-and-pop operation with no hired hands, but a line of anxious farmers waiting to unload their grain before it starts raining—is often evoked in this line of argument. Some country elevators have little need for dust control because they have low throughput and no enclosed bucket elevators. Others, it is argued, lack the resources to purchase dust collection systems or hire additional labor. The appropriate action level, if there is such a thing, varies significantly by facility, and the small ones should, the argument continues, be spared the regulatory rod entirely.

This position on dust control contradicts the position taken else-

where in 61B. The Agricultural Dusts committee has gone on record several times against the notion that differences in facilities render a general standard inappropriate. Separate NFPA standards for country elevators were combined with those for other grain-handling facilities in 1973, when the committee decided that "a distinction between types of grain elevators on the basis of capacity or shipping or receiving media is no longer practical."[25] Similarly, a committee member argued in July 1985 that motion switches should not be mandated on all bucket elevator legs because some country elevators "do not realistically need them." The committee rejected the argument on the grounds that motion switches were generally a good idea and it would be impossible to identify in a standard those situations in which they are not necessary.[26] The same could be said about dust-control requirements. "Facilities vary," notes a former USDA investigator, "but the hazard scenarios are the same."

The Unspoken Arguments: Liability and Retroactivity

So why is the housekeeping provision in 61B so vague? Two factors other than the limitations of science and the diversity of facilities are at play. One is specific to this issue, the other indicative of a larger force affecting the development of private safety standards. There is an unspoken belief that good housekeeping simply is not the answer. To some, it is a matter of practicality. It would require excessive effort, the argument goes, to keep an elevator clean enough to prevent explosions. "There is no such thing as a clean elevator," quipped one trade association representative. Perhaps the strongest explanation is that a specific housekeeping provision could be legal dynamite. Industry has learned that voluntary standards can and will be used against you in a court of law. Most explosions lead to litigation. According to a retired Cargill executive who testifies in such lawsuits, 61B and a host of related standards are raised in almost every case. The stakes can be very high. The two largest explosions in 1977 resulted in settlements of approximately $25 million each, and a jury recently applied the bane of the tort law—punitive damages—for the first time in a grain elevator case.[27] The vaguer 61B is on housekeeping, the less powerful a weapon it would be after an explosion.[28] Some of the vagueness, then, is simply an attempt to make the standard liability-proof. The ill-fated OSHA citations that relied on 61B are testimony to the effectiveness of this strategy.

Success, in this context, breeds more generalities. Substituting what Agricultural Dusts committee members refer to as "motherhood statements" for specific provisions is an increasing trend with 61B. Space heaters shall be located in "suitable places." Fire extinguishers shall be located in "strategic" places. A proposal that all bearings be properly maintained in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications was rejected by the committee in 1985 in favor of a requirement that "all bearings shall be properly maintained."[29] ("Let's see what a lawyer can do with that one!" mused a committee member at the July 1985 meeting.) Of course, the ability of lawyers to "do something" with the standard is probably equal to (or greater than) the standard's usefulness to its intended audience, grain elevator operators. Without guidance concerning the specifics of "proper maintenance," the lawyers will be as lost as anyone trying to glean any substance from the standard.

The extent to which 61B should contain such generalities appears to be the most significant issue facing the Agricultural Dusts committee. Some think that the committee has gone too far already. The president of one of the only two insurance companies presently underwriting grain elevators—major companies such as Cargill are self-insured—abhors the generality. He considers 61B so vague as to provide no real assistance in evaluating elevator safety. He does not even keep a current copy of the standard in his office. The technical director of the National Grain and Feed Association, on the other hand, considers such generalities the silver lining to an otherwise objectionable standard.

The generality problem indicates a more significant dilemma. The committee is trying to achieve two largely incompatible objectives: having a meaningful standard that can affect safety and provide helpful guidance to elevator operators without providing ammunition that will be used against you whenever an explosion occurs. Nowhere are the dimensions of this problem more accentuated than in respect to retroactivity.

By its own terms, 61B applies only to new facilities. This makes the most sense for design requirements. Compliance costs for many requirements are low in the design stage but very high after construction. Elevators used to be built with combustible materials, for example, and little consideration was given to minimizing ledges and horizontal surfaces or designing conveyors in a manner that would facilitate cleaning with portable vacuum cleaners. These things can easily be remedied in the design process. Correcting them retroactively would practically involve building a new facility.

In reality, 61B can, has, and will be applied to situations other than brand-new elevators. When issuing citations, OSHA often refers to 61B without regard for the date the facility was constructed. Plaintiff's attorneys are similarly inclined and have met with greater success. The retroactivity clause invites this attitude. NFPA 61B attempts to be unusually lenient in this regard. Unlike most building codes, it does not even require compliance in the case of major expansion or renovation—the vast majority of "new" construction. Moreover, the 1980 version also exempted from retroactive coverage a host of operational activities—such as hot-work procedures and housekeeping—that can be carried out without regard to the age or design of the facility.

The opposing viewpoints about retroactivity reflect deep-seated differences concerning the role and nature of private standards. Some of those favoring the broadest possible exemption from retroactive application "really do not want a standard at all," according to an Agricultural Dusts committee member at the July 1985 meeting.[30] This group is not insignificant. The National Grain and Feed Association, the largest trade association in the field, is unwilling to refer to 61B as a national consensus standard and refuses to participate on any of NFPA's agricultural dust committees.

The implications of this reticence are not lost on the Agricultural Dusts committee. Organized opposition can prevent or at least postpone proposals from being adopted in the NFPA system. Should this private standard become unpalatable enough to the NFPA, or if others in the industry actively opposed it, 61B might fall of its own weight. As one committee member said at the July 1985 meeting, "It behooves us to try and give some relief to those being sued." Nevertheless, most committee members realize that the only real "protection" against retroactive application is to abolish the standard. They understand that others will do as they please in interpreting the retroactive effect of 61B, so it is futile to attempt to prevent this from happening by tinkering with the retroactivity clause. These members also see the danger in exempting too many requirements from retroactive effect. "If this [standard] is too unattractive to the states," warned another committee member at the same meeting, "they might adopt their own requirements." Several proposals to strengthen the tone of the retroactivity clause were rejected in July 1985 primarily because they seemed pointless to the committee.

To the chagrin of those proposing the stronger exemption, the committee adopted a proposal by the representative from Continental Grain

to narrow the scope of the retroactivity clause—that is, to make more provisions apply retroactively. The only provisions in the 1980 version with retroactive effect concerned fumigant usage. In seeking to identify appropriate candidates for retroactive application, the intent, according to the committee chairman, was to include "operational" requirements but not those requiring "even a dime of investment."

The results of the 1985 revisions are revealing because the committee chose to include the housekeeping provisions in the group to be given retroactive effect. This change appears to make 61B more credible. After all, shouldn't old and new facilities alike be expected to do proper maintenance or take precautions to ensure that welding is done safely? In light of the "not even a dime of investment" principle, however, the committee's action seems more significant for what it admits about the housekeeping provisions—that they do not require anything more than what an operator is already doing.

The Uneasy Solution: Change the Packaging

In an effort to placate those who would rather not have a standard, the Agricultural Dusts committee has done everything possible to make 61B a more agreeable document. These changes have largely been a matter of form, not substance. The language in 61B has been toned down considerably over time. References to such unpleasantnesses as "injuries to personnel" have been replaced with less specific references to hazards in general.[31] The introduction to the 1959 version of 61B warned that: "GOOD HOUSEKEEPING AND CLEAN PREMISES ARE THE FIRST ESSENTIALS IN THE ELIMINATION OF DUST EXPLOSION HAZARDS, CONSEQUENTLY THIS CODE IS NOT INTENDED TO LESSEN IN ANY WAY THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE OWNER AND OPERATOR IN THIS RESPECT ." This language was moved to the appendix in 1973, and the capital letters were replaced with regular capitalization. The statement was omitted entirely in the 1980 version.[32] Only the gentlemen's agreement remains.

Placing things in the appendix is a popular compromise. Fully one-third of the 1980 version of 61B is appendix material. The appeal of this compromise is clear: the individual in favor of the material gets it "into the standard" in some form, while those opposed to the specifics take considerable solace in the fact that it is "not a requirement." Employee health and safety, a subject avoided in many NFPA standards but favored by the labor representative on the 61B committee, is addressed in an appendix added in 1980.

The appendix also contains more specifics than the actual standard. For example, the standard requires that "horizontal surfaces shall be minimized," while the appendix indicates that the "suggested angle of repose is 60 degrees."[33] This is another tactic in the search for a liability-proof standard. The hope is that through the appendix the generalities in 61B can be given meaning in a nonenforceable manner. The official NFPA position, set forth in every standard, is that the appendix "is not part of the requirements … but is included for informational purposes only." Of course, one of the stated purposes of NFPA's "requirements" is to provide information.

The difference is really a matter of wishful thinking. All NFPA "requirements" are informational until an "authority having jurisdiction" chooses to enforce them. Moreover, the authority can choose to enforce the appendix as well as the "requirements" proper. An NFPA member who has worked with this committee confirms that appendix material is often treated by state fire marshals as having equal weight to the "requirements." The wishful thinking paid off, however, in the case of grain elevators. Some OSHA citations were overturned by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission precisely because they relied on material contained in the appendix of 61B.[34]

Technical Arguments, Surprising Results

This is not to say that 61B is all appendix and no substance. Nor is it to say that disagreements are foreign to the Agricultural Dusts committee. Certain provisions in 61B are specific and have been the source of repeated debate throughout the years. Should there be a vent between bins to allow dust generated during loading to settle into adjoining bins instead of blowing back up into the work area? To what extent is it possible or desirable to vent silos and elevator legs to relieve pressure from an explosion? Should compressed air be allowed, and under what circumstances, to "blow down" dust from walls and rafters?

The technical nature of these questions is not surprising. Private standards-setting is often described as technical. Esoteric questions such as those above seem to fit the bill. How the committee has handled these issues is more unusual. "Irrational," "unrealistic," and "unduly stringent"—criticisms often reserved for government regulation—are all strictures used by some NFPA members to describe the resolution of these issues.

For example, even though most insurance and grain company rep-

resentatives privately concede that the requirement is irrational, 61B prohibits interbin venting,[35] and it is also accused of being unrealistic about explosion venting. (Explosion vents are movable panels designed to vent the pressure from an actual explosion; interbin vents, just discussed, are actual openings designed to vent airborne dust.)[36]

NFPA 61B includes several other provisions that are considered by many in the grain industry to be too stringent. Removing layered dust with compressed air is prohibited unless other equipment is shut off. The concern is that "blowing down" can create a combustible cloud. There are no known cases in which an explosion has occurred this way, and one insurance representative expressed serious doubts about whether compressed air could create dust concentrations above the LEL. The only explanation for this provision is that it represents a compromise between those who are opposed to blowing down on principle and those who think that it is never dangerous.

Requirements incorporating the National Electric Code's classifications for environments with agricultural dust are also quite strict. The code, written by NFPA, specifies two classes for such environments: Divisions 1 and 2.[37] Equipment certified for Division 1 must be tested under conditions in which dust concentrations regularly exceed the LEL. Equipment for Division 2 is tested under conditions in which such concentrations are "occasionally" encountered. Herein lies the controversy. Division 2 equipment is tested under extreme conditions compared to those normally encountered in those parts of a grain elevator where Division 2 equipment is required. The Division 2 test methods do not just represent the worst case, they represent an impossible case.[38] Not only does this provision increase the price of grain-handling equipment, but in some cases the required equipment is not available. The same arguments apply to Division 1 equipment if it is required in areas without explosive dust clouds. The NFPA leaves these implementation questions to "the authority having jurisdiction."

NFPA 61B is also stringent with respect to ignition sources in bucket elevators, but this is a recent development. Several requirements for bucket elevators were added in 1980, including (1) monitoring devices that cut off the power to the drive and sound an alarm when the leg belt slows down, (2) magnets or separator devices to minimize metal objects entering the grain stream, and (3) closing devices to prevent flame propagation through idle spouts.[39] These requirements did not generate the controvery produced by those discussed above. Neither were they really new; they were moved from the appendix to the body

of the standard. This unusual move is best understood by the politics of the moment. The changes were suggested around the time OSHA initiated its Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. Some committee members privately acknowledge that these changes were an attempt to forestall OSHA regulation. The changes certainly strengthened the standard, at least for new construction. But they did not forestall OSHA.

The OSHA Standard

Grain elevator operators did not have a very merry Christmas in 1977. Three grain elevators and two feed mills exploded during the third week of December, killing fifty-nine people and injuring forty-eight others. The Department of Agriculture, hit particularly hard because thirteen federal grain inspectors were killed in the explosions, established a Special Office for Grain Elevator Safety. OSHA was put on the spot. There was intense political pressure to do something about grain elevator safety, but OSHA had little experience with the issue. Lacking its own safety standard, the agency had only its "general duty" clause to back up any enforcement actions. Citations based on this clause require, among other things, proof of a "recognized hazard."[40] NFPA 61B came in handy, since one possible method of establishing a "recognized hazard" is to cite private standards. OSHA did so on numerous occasions after the 1977 explosions. Citations tend to evoke indignation, however, and these cases were no exception. Some of the citations lived up to the agency's reputation for unreasonableness—one firm was cited for an ungrounded coffee pot in an office building detached from the grain elevator, for example—but even those involving seemingly serious violations were met with hostility. Virtually every citation was contested, and OSHA lost almost every one on appeal: 61B was considered too vague in some instances; in others, the review commission that hears appeals from OSHA citations honored the "advisory" nature of the appendix. OSHA had to look elsewhere to advance its enforcement strategy.

To overcome its limited background in grain elevator safety, and in the hope of defusing an already politicized issue, OSHA contracted with the National Academy of Sciences to evaluate possible methods of preventing grain elevator explosions. The first of four NAS reports confirmed the inadequacies of OSHA's experience, criticizing the agency

for emphasizing citations instead of investigating explosions sufficiently to understand the problem.[41]

OSHA adopted a cautious, if not timid, stance. In January 1980, the same month that the Department of Agriculture released its report "Prevention of Dust Explosions—An Achievable Goal," OSHA issued a "request for comments and information and notice of informal public meetings," which posed approximately two hundred questions for public comment.[42] Although it was widely assumed that OSHA intended to propose a grain elevator safety standard, the agency did not start drafting one for two more years. It was waiting for support from the NAS. Testing the political waters in the meantime, OSHA held hearings a few months later in Wisconsin, Louisiana, and Missouri.

The water was hot. The hearings opened an acrimonious debate that shifted locations over the years but never lost its political intensity. Several hundred comments were received in response to OSHA's request, and over two thousand pages of testimony were received at three "informal public meetings." Most of it was extremely negative. This hostility hindered the NAS, which noted the "reluctance of elevator management to cooperate" with their study.[43] The key report, "Prevention of Grain Elevator and Mill Explosions," was released in June 1982.[44] It identified as the two most significant issues in grain elevator safety (1) ignition sources in bucket elevators and (2) dust concentrations throughout facilities. With this background, OSHA began drafting a standard for grain elevators. Within a month, the head of OSHA told a House subcommittee that grain elevator safety was one of the agency's two priority projects, and that a rule would be completed by January 1983.[45] It took much longer than expected, but the agency eventually proposed a regulation, with fourteen basic requirements.[46] Many of these, particularly those concerning ignition-source control in bucket elevators, came directly from the NAS recommendations. One received practically all of the attention: the "action level" for removing layered dust.[47]

Hanging a Number on Dust Control

The action-level concept came from the NAS report, which proposed that corrective action should be taken whenever layered dust exceeded a specified depth (over a 200-square foot area). The NAS did what the NFPA would not: hang a number on dust control. "It was done to satisfy labor and other political groups who felt that without a definite

figure you do not have a club," explains an industry member on the NAS panel. The panel chose one sixty-fourth of an inch as its "club."[48] The number was a compromise, plain and simple. Some panel members argued for one-hundredth of an inch, based on flame propagation experiments and without regard for economic feasibility. One-eighth of an inch, a figure already used in some proprietary standards, was also suggested. One sixty-fourth was somewhere in between.

OSHA engaged in its own search for an agreeable number. Again, the process was predominately political, not scientific. Under more pressure than NAS to take into account the economic impact of its proposals, OSHA considered a higher range of numbers. The argument was between one sixty-fourth and one-eighth. The former had new-found credibility thanks to the NAS; the latter had historical acceptance. OSHA chose historical acceptance.

The selected number appears to have been favorable to industry. The rejected figure (one sixty-fourth) was, after all, eight times stricter than the one chosen. One-eighth is considered by many to be not only lenient but downright dangerous. An elevator with an eighth of an inch of layered dust, according to an insurance representative, is "a bomb waiting to explode."

But appearances can be deceiving. Industry opposed one-eighth and one sixty-fourth with practically equal vigor. In reality, the disagreement was not about the best action levels; it was about whether to have action levels at all. OSHA wanted a number. Industry did not. "You've got to have a number for it to be enforceable," according to an OSHA official familiar with the agency's bad luck under the general duty clause. For related reasons, industry was opposed to any number. Although it cited the specter of dangerous facilities being in compliance with the rule—those with one-ninth of an inch of dust, for example—industry's real concern was the opposite: seemingly safe facilities being in violation. It is likely that even the best facilities would at some time, in some part of the facility, be in violation of the one-eighth-inch requirement. This would not be a problem if OSHA could be trusted to use good judgment in enforcing the rule. But most elevator operators did not have such confidence. As a result, unreasonable enforcement strategy was of much greater concern than the "false sense of security" some claimed would follow from an action-level approach.[49] The paramount concerns of the National Grain and Feed Association when it later petitioned for a partial stay of the OSHA regulation were the enforcement directives for implementing the housekeeping require-

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ments.[50] Unfortunately, the enforcement strategy, including possible methods for heading off unreasonableness, was never seriously discussed during the rulemaking proceedings. Instead, the debate was dominated by a battle of the cost-benefit analysts. The issues they raised were important, but so were many of the ones they ignored.

The Battle of the Cost-Benefit Analysts

The battle itself was costly. First OSHA hired a well-known consulting firm (Arthur D. Little) to analyze its draft proposal. The resulting report was riddled with errors and questionable assumptions.[51] It was so vulnerable to attack that OSHA hired a second firm (Booz, Allen & Hamilton) to massage the data. The NGFA subsequently hired a third consulting firm (G.E.M. Consultants) to attack the conclusions reached by the first two.

On the cost side, estimates prepared for OSHA by Booz, Allen pegged the total initial cost of the standard at $200 million, with annual recurring costs of approximately $137 million. These estimates reflected a series of assumptions about the cost of each of the fourteen provisions in the proposed rule.[52] Industry accepted the Booz, Allen estimates for some of the minor provisions, such as permit systems for hot work (see table 5), but it took issue with most of the others. By

making marginally higher estimates for almost every subsidiary assumption, industry argued that the cost of many provisions were understated by a factor of two.[53] Except for the housekeeping provisions, these differences of opinion did not add up to much. Hundreds of millions of dollars, however, separated the cost estimates for housekeeping. Some of these differences are impossible to evaluate.[54] Other assumptions made by OSHA's consultant seem more reasonable than the industry's.[55] Industry also offered some persuasive indictments of the OSHA estimates. The Booz, Allen study assumed that operators would purchase "dust-tight" vacuum cleaners, even though the National Electric Code requires the more expensive models certified for class (g) environments. In short, it seems safe to assume that the true cost of the rule would fall in between the estimates prepared by the two consultants.

On the benefit side, where estimates are normally subject to more uncertainty, the report prepared for OSHA took a realistic position. It was assumed that the housekeeping provision would prevent approximately 30–50 percent of all fires and 17–32 percent of all explosions. Through a series of calculations intended to gauge the "willingness-to-pay" to avoid property damage and personal injuries, these figures produced an estimated total benefit of approximately $286 million.[56] Industry did not take issue with the specifics of these estimates. Although it is always arguable that things will not work out as well as planned, the estimates prepared for OSHA were not vulnerable to the charge of overoptimism.

The battle of the cost-benefit analysts was not won clearly by either side. Assuming that actual benefits would be between 50 and 90 percent of OSHA's (possibly high) estimates, the rule would yield from $143 million to $286 million in total annual benefits. Estimates of annualized cost, based on the figures presented in table 5 and discounted to present value, ranged from $113 million (OSHA) to $240 million (NGFA). The true cost is likely to be somewhere in between. Therefore, the OSHA standard may or may not generate more benefits in excess of costs—a plausible case can be made for both propositions. Either way, the costs appear to be in the same ballpark as the benefits.

Country Elevators and Distributional Effects

Aside from cost-effectiveness, the standard was controversial for distributional reasons. Industry and OMB argued that the rule dispropor-

tionately affected country elevators. Between 80 and 100 percent of export terminals and inland elevators were thought to be in compliance with most of the OSHA requirements (other than housekeeping). No more than 15 percent of country elevators were. Large facilities generally had dust-control programs; many country elevators did not. As a result, the costs of the proposal fell much more on country elevators than on other facilities. Yet, as OMB argued, the risks were more significant in larger facilities.[57] OMB took the position that "big" facilities should be covered and "small country elevators" should not. OSHA did not want to exclude any facilities. As an OSHA official testified, "When workers are hurt or killed [we] don't particularly care about the size of the facility." Both positions were less than reasonable. OMB wanted to exempt all "country" elevators, even though some were, by any measure, as large as inland terminals and export facilities. But OSHA's position indicated complete disregard for marginal costs and benefits. The cost of bringing the smallest facilities into compliance would be far out of proportion to the losses likely to occur in those facilities.

A political dispute of surprising dimensions took shape. Both the vice president of the United States and the president of the AFL-CIO got involved when OMB held up the rule for months longer than the normal sixty-day review period. The housekeeping provision was the major bone of contention. In a compromise that pleased practically no one, the proposed rule was released for publication when OSHA, at OMB's insistence, added two alternative proposals for housekeeping: sweeping once per shift or installing pneumatic dust control.[58] It was no secret that OSHA still favored the action-level alternative.

The added alternatives did not cool the political debate. The NGFA organized an impressive campaign to flood OSHA with "worksheets" from elevator operators opposed to all three alternatives.[59] A few congressmen held hearings to allow elevator operators in their home districts to complain that "the people who wrote these standards have never been to a country elevator."[60] OSHA continued to take heat from all sides, with the exception of labor. In what was termed an "unusual alliance," the AFL-CIO supported the proposed rule even though it would have preferred an action level stricter than one-eighth of an inch.[61]

The OSHA Standard Prevails (with Minor Improvements)

The stalemate between OMB and OSHA lasted until there were two more serious explosions. In July 1987, following a fatal explosion in

Burlington, Iowa, Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) complained to the OMB director about delays in releasing the rule. He complained again four months later, following another explosion. The rule was published on the last day of 1987.[62]

The rule contains a major change, but not an actual softening, in OSHA's position on housekeeping. The standard retains the action level of one-eight of an inch for housekeeping—eliminating the ineffective "once-a-shift sweeping" option. OSHA modified the provision, however, by limiting its application to three "priority areas."[63] This seems much more reasonable than the earlier version, which applied to any 200-square-foot area in the facility. It may even help reduce frivolous or unreasonable enforcement actions. But it does little to alter the basic housekeeping tasks required by the rule, since many of the steps used to minimize grain dust in "critical" areas will also minimize it elsewhere. OSHA also moderated the rule slightly to favor country elevators. Some country elevators are exempt from the requirements for alignment and motion detection devices.[64] But none are exempt from the action-level requirement. Country elevators were given three extra years to come into compliance, however. The symbolism of these changes, all conciliatory, far exceeds their actual substantive impact.

The most substantial change in the final standard concerned feed mills, and again the adjustment was in the direction of leniency. In response to arguments that risks are lower in feed mills, OSHA exempted these facilities from the most powerful provisions in the standard: the housekeeping and bucket elevator requirements. OSHA defended this decision, calculating that "the risk of an employee death or injury resulting from an explosion is almost five times greater in grain elevators than in mills."[65] OSHA rejected this line of argument in the case of country elevators, however, justifying the apparent discrepancy on the grounds that "the available data are not sufficient to permit an accurate estimate of the relative risks in large and small elevators."[66] Although nobody was entirely pleased with the final standard, it certainly was reasonable in many respects. An editorial in the trade journal Feedstuffs, often an outspoken critic of OSHA, allowed that "grain elevators and feed mills can be much safer places to work merely as a result of OSHA's attention…. The rules on bin and entry, housekeeping plans, work permits, etc., are needed. A federal edict appears to be the best way to implement such rules."[67] But industry was incensed at the housekeeping requirements and immediately challenged them in court. Labor countered, challenging the exemption for feed mills. The

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld all but the housekeeping provisions, remanding that issue for "reconsideration of the economic feasibility of the standard."[68]

Summary Evaluation

The OSHA standard is a classic example of the time-consuming adversary process often attributed to government regulation. Ten years elapsed between the 1977 explosions and the final OSHA rule. The most controversial issue, housekeeping, remains unresolved after a court challenge, even though OSHA spent at least half a million dollars on consulting firms. Hearings held around the country produced volumes of testimony, mostly to the ill will of industry toward OSHA. The standard was loosened somewhat during this arduous administrative process. Whether these changes were a victory for business or a calculated bargaining strategy by OSHA depends on whom you ask. Whatever the reason, OSHA exempted small facilities from some requirements and extended the deadline for compliance with others. OSHA also restricted the final standard to bulk grain-handling facilities, exempting feed mills and other processing facilities included in the original proposal. Most important, OSHA concentrated the housekeeping provisions in three "critical" areas. These changes all made the standard more reasonable.

OSHA's final standard has fewer requirements but packs more punch than NFPA 61B. OSHA stood firm on the action-level approach to housekeeping, resisting strong political pressure to weaken the provision by allowing sweeping once per shift. The agency adopted an action level identical to that used in several proprietary standards, which, if anything, is too lenient (the NAS suggested a more stringent level). The standard is strict enough to cover the worst facilities, however. (These "bad apples" are estimated to constitute 10 to 30 percent of the facilities.) OSHA's housekeeping requirements also have the advantage of being performance-based, allowing firms to determine the most efficient method of compliance. The overall cost of compliance is difficult to estimate, but the range of estimated costs is lower than the range of estimated benefits.

In contrast, the NFPA standard bears out the common conception that private regulation is weaker than its public counterpart. To NFPA's credit, its committee meetings are not plagued by adversity or delays. Committee members are knowledgeable, bringing an array of practical

experience to the task. They meet regularly and adopt revisions in relatively short order. But the outcome (at least in the case of grain elevators) leaves much to be desired. NFPA 61B is relatively spineless. Many important topics, including housekeeping, are glossed over with empty generalities. This situation is due in part to concerns about liability. Seeking to avoid a standard that can be used against business in any post-explosion lawsuits, the Agricultural Dusts committee relegates many issues to the appendix, while making others intentionally vague. The committee also shares the sense that certain "management" issues should not be subject to industrywide regulation. A representative of the Grain Elevator and Processors Society disavows "any kind of declarative 'thou shalt do so-and-so'" standard.[69]

Not all aspects of the NFPA standard are as flimsy as the housekeeping provisions: 61B is fairly strong on basic design issues. Because of the retroactivity clause, however, these provisions apply to fewer facilities every time the standard is upgraded. This technique minimizes political opposition and helps explain why upgrading is possible. Some provisions of general application are also strict, a few to the point of being unreasonable. Provisions such as the UL specifications for equipment used in hazardous locations are far more demanding than is warranted by the circumstances. These provisions require expensive electrical devices where normal equipment would pose no real hazard. Other requirements, aimed at reducing fire hazards more than explosion hazards, may actually be counterproductive—reducing the former at the expense of increasing the latter.

These unexpected tendencies are not major aspects of 61B; they are noteworthy because they are evidence of a "technical" decisionmaking realm characterized by influences and behavior not normally attributed to the private sector. These "technical" decisions reflect the professional norms of engineers. This engineering ethic is conservative in some respects and stringent in others. Engineers are loathe to get involved with political issues, including matters of management prerogative, but they are zealous advocates of safety on occasion. OSHA has no quarrel with the fire safety provisions in NFPA 61B. The extent to which private standards-setters are influenced by regulatory philosophy and professional ethics is explored in detail in chapter 7.