2—

Islamic Quarters in Western Cities

The Midway Plaisance . . . bears the same relation to the Exposition that the sideshows have to the circus. [Here are] German, Irish, Austrian, Turkish, Javanese, and Egyptian villages, mosques, kiosks, and pagodas, menageries, panoramas, casinos, cliff-dwellers, snake-charmers, Esquimaux. . . . It is . . . a vivacious, cosmopolitan medley.

Chicago Tribune, 30 April 1893

London's Great Exhibition of 1851 opened a new era of international and cross-cultural communication. The Crystal Palace was the architectural centerpiece of this event—an iron and glass monument that served for a time as the model for exhibition halls. It was a large single hall that could be divided by partitions. As the exhibitions assumed increasingly important commercial and sociocultural roles and grew larger, however, such huge marketlike structures were no longer adequate. To portray the entire human experience—and to convey the flavor of the places represented—required a different kind of exhibition space.

By 1867 the desire for more authentic cultural representations—especially of more exotic and unfamiliar places—led to the construction of independent structures for indigenous displays. In carefully grouped constellations, these displays represented various parts of the world. To make them more realistic, people wearing their local costumes and "acting out" their typical daily activities were added.

The design of the exhibition grounds thus changed to include both an area in the Beaux-Arts manner, axial and symmetrical, with imposing structures for the main exhibition (in the tradition of the Crystal Palace) and a "picturesque" arrangement of buildings scattered in the surrounding parks and gardens. The site planning also graphically signified power relations among the exhibiting countries. It portrayed a world where races and nations occupied fixed places determined by the exposition committees of the host countries. Thus the host nation occupied the center; the other industrial powers surrounded it; colonies and other non-Western nations were relegated to the peripheries.[1]

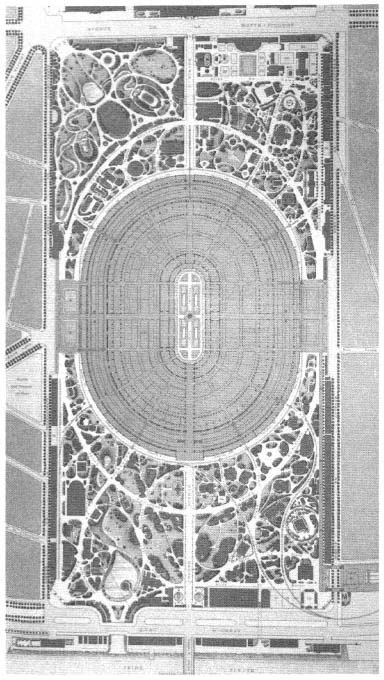

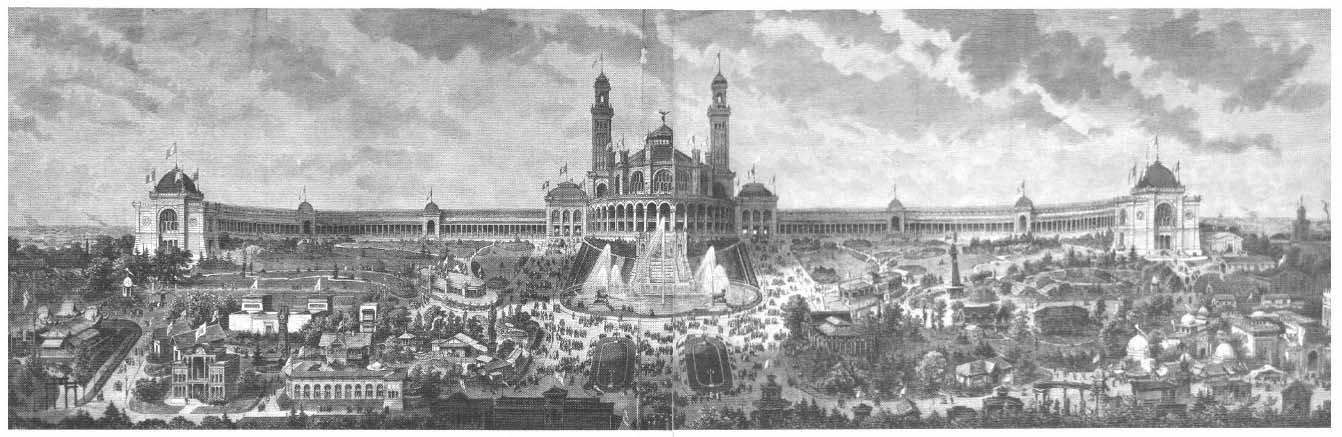

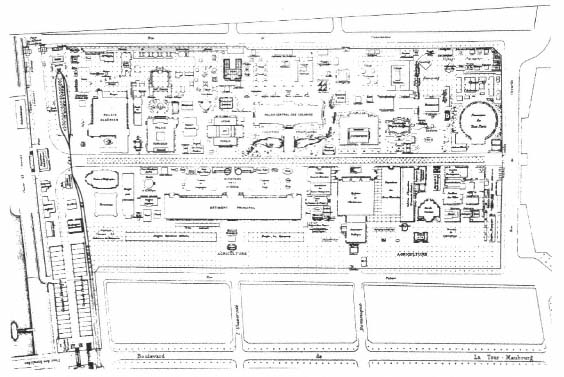

The two-part organization was a characterizing feature of the 1867 exposition on the Champ de Mars, and the park was considered one of the main in-

novation (Fig. 18). Alfred Normand, in his learned account of the architecture of the different sections, emphasized the gardens surrounding the exhibition as "the necessary complement of the ensemble, the spectacle without equal."[2] Giving all nations the opportunity to represent themselves architecturally was a main goal in 1867. Indeed, the exhibition hall itself had been designed by the Saint-Simonian engineer Frédéric Le Play to suggest a brotherly aggregation. Its oval shape (the structure, first conceived as a circle, was changed to better fit it to the site) symbolized the globe; the hall was divided into seven concentric galleries, each reserved for a particular purpose. Industry was at the outside, followed by clothing, furniture, raw materials, history of labor, fine arts, and, in the center, a garden. Transverse segments, given to different nations, divided the concentric galleries. A visitor who walked from the outermost gallery toward the center could see all the products of one nation; a visitor who walked each concentric gallery would be able to compare the similar products of different nations.[3]

Although the park was intended to signify the peaceful gathering of nations, in reality it introduced, and even reinforced, division, in both its spatial organization and its architecture. Hippolyte Gautier remarked that outside the external walls of the "circus" was a crowd of "bizarre constructions . . . a strange city, composed of specimens from all kinds of architecture." Walking through this section seemed like taking a world tour in miniature. It was no longer necessary to take the boat from Marseilles.[4]

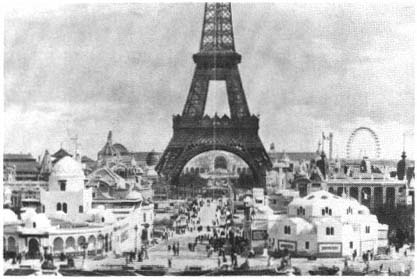

In scale and in architecture the major exposition structures differed notably from the indigenous quarters surrounding them. The main buildings were conspicuously located, self-conscious architectural monuments: the Eiffel Tower and the Galerie des Machines of the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris, celebrating the spirit of the industrial age; the neoclassical buildings of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago; the Grand Palais and Petit Palais of the 1900 Paris Universal Exhibition. The pavilions in the parks and gardens, in contrast, were replicas in miniature of buildings in a variety of architectural styles from various cultures. Their scattered sitting and the landscape around them reinforced their modesty.

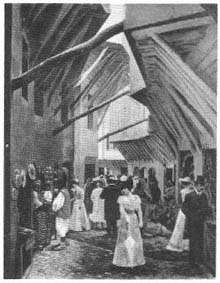

The main exposition halls and the quarters at the periphery differed, moreover, in their overall atmosphere. In the indigenous quarters the ambience was enriched by representatives of different cultures dressed in their most pictur-

Figure 18.

Plan of Exposition universelle, Paris, 1867 (A. Alphand, Les

Promenades de Paris, 1867–73).

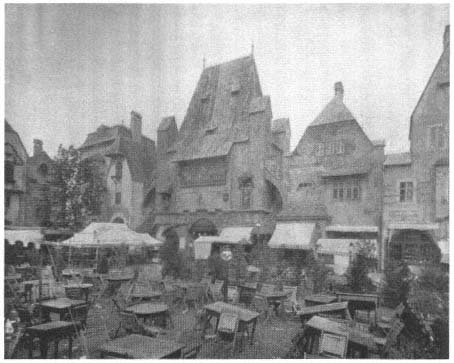

Figure 19.

Old Vienna, Chicago, 1893 (World's Columbian Exposition, vol. 2).

esque clothing. Artisans worked in the pavilions, traditional music played, and authentic food was served, unfamiliar sights and sounds mixing with exotic smells. As the urban historian and sociologist Janet Abu-Lughod argues, urban character is a matter not only of form but also of other sensuous cues.[5] The indigenous displays in nineteenth-century world's fairs appealed to all the senses and thus created the atmosphere of the places represented.

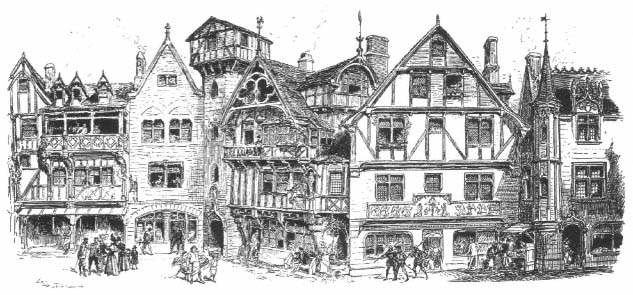

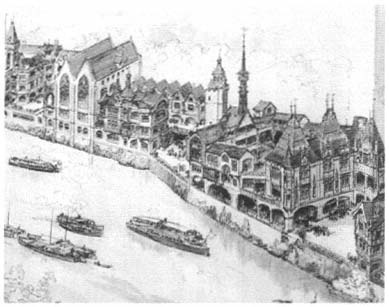

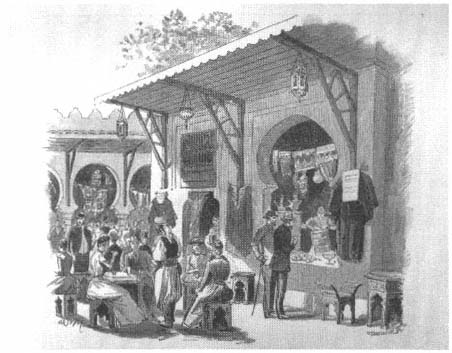

The peripheries were not reserved exclusively for non-Western cultures. There, all the nations displayed a lighter side, with the emphasis on entertainment rather than progress and economic power. For example, in Paris in 1867 the French quarter pavilions re-created the country's historical periods: a small Gothic church, a miniature Panthéon, and a Bastille Tower were scattered in a picturesque garden. Old Vienna, with its medieval architecture and beer gardens, was brought to Chicago in 1893 (Fig. 19). "Old Paris" was reconstructed on the Quai de Billy in 1900 as a collage of pavilions representing the Sainte-Chapelle, the Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the Cloisters of the Collège de Cluny, the Tower of the Louvre, and other structures (Fig. 20–21). Technology in the

Figure 20.

Rue des Vieilles-Ecoles, Paris, 1900 (L'Esposizione universale del 1900 a Parigi, Milan, 1901).

Figure 21.

Vieux Paris, Quai de Billy, Paris, 1900 ( Exposition de Paris, vol. 1).

displays at the periphery was presented as a curiosity: in 1867, France and England each erected a "lighthouse" powered by electricity.[6] Furthermore, as entrepreneurs learned to capitalize on the crowds of visitors to the expositions, quarters devoted to entertainment appeared at the outskirts of the fairgrounds. In Paris in 1889 an amusement park called the Pays de Fées was built on the Avenue de Rapp outside the gates of the fair.

In the design of the Islamic sections, particular attention was paid to "authenticity"—both of architecture and of atmosphere. The obsession with authenticity is generally associated with nineteenth-century Orientalist painters,[7] who represented architectural settings as combinations of architectural forms, fragments, and details of buildings from different places and time periods. They achieved "accuracy" not by representing particular buildings but by minutely rendering architectural details. A similar method was employed in the construction of exhibition pavilions, which were often architectural collages incorporating various periods and regions of Islamic civilization.

The art historian Linda Nochlin argues that in the realism of the Orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme's works, a "plethora of authenticating details" went hand in hand with the idea of mystery and the absence of certain themes, such as history. The world represented was timeless, its customs and rituals atemporal.[8] The exhibition pavilions suggested mystery in their symbolically loaded architectural details (the intricate arabesques, the wooden latticework of the windows that connoted the seclusion of women); the decorative, often unintelligible, calligraphy on the walls; and the "curious" performances and unfamiliar musical instruments. They were also characterized by their ahistoricism, with different periods and regions often collapsed into single structures. Cultural dynamics, as expressed through architecture, were overshadowed by what was considered typical, representative, and, ultimately, timeless. Architecturally frozen in an ambiguous and distant past, Islamic cultures at the universal expositions were presented as incapable of change and advancement.

Although these themes generally determined the placement and architectural image of the Islamic quarters at expositions, the planning principles were not always the same. The changes that occurred from 1867 to 1900 mark shifts in power relations and in the struggle for Islamic and national cultural identity. An analysis of the changes sheds light on the internal logic of the exhibitions as diagrams of a world order.

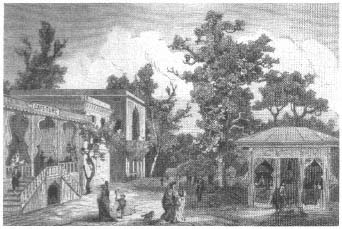

Universal Exposition of 1867, Paris

As representatives of Islamic urban settings, Ottoman and Egyptian quarters were placed adjacent to each other in 1867 in Paris, and, despite their independent designs, they formed an ensemble: visitors could meander through the Egyptian street into the Turkish square. Both quarters were deliberately made irregular to reflect the tortuous streets with many dead ends of Islamic cities. The choice of an irregular urban fabric to represent Istanbul and Cairo at the fairs reflects one of the dilemmas of Ottoman and Egyptian officials and their European advisors. Even though in both Istanbul and Cairo the 1860s were marked by an intense campaign to regularize the network of streets, to create monumental avenues and vistas, and to establish large urban squares—all lessons learned from Haussmann's rebuilding of Paris—the exposition planners turned to the past, to an image that they considered outdated but that the West associated with Islam.

As I mentioned in the introduction, the definition of cultural identity was much debated among the Westernizing Turks and Egyptians during this intense period of sociocultural transformation. Some called for maintaining the old cultural forms while adopting Western technology; others wanted either to incorporate new elements into the local culture, thereby creating a rupture between the old and the new, or to evaluate and redefine their self-identity according to Western views. The architectural representations of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire in Paris in 1867 belong to the latter trend.

The Egyptian quarter at the 1867 fair consisted of three buildings on a street: a temple, a selamlik (a small palace), and an okel (a covered market, or caravansary) (see Figs. 70–75). The temple, a replica of the temple of Philae, was a museum where antiquities were exhibited; an avenue lined with sphinxes led to its entrance. Together, the temple, selamlik, and okel were intended to convey the complete history of Egypt. The temple stood for Egyptian antiquity, the selamlik for the nation's Arab civilization, and the okel for contemporary industrial and commercial life. Between the okel and the temple was a copy of Bartholdi's statue of the famous Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion, who seemed to meditate on a future when "the veil covering forty centuries of history would be torn."[9] A pavilion called the Isthme de Suez displayed docu-

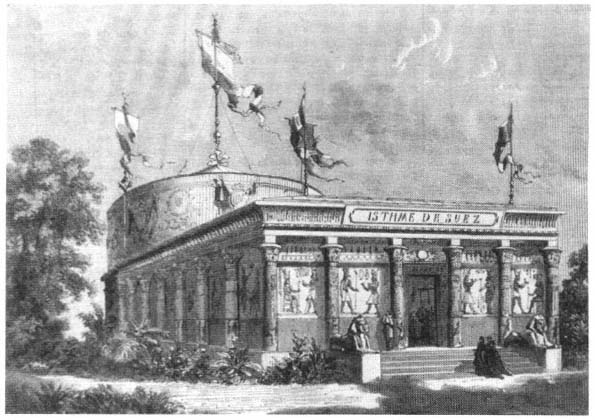

Figure 22.

Suez pavillon, Paris, 1867 (L'Exposition universelle de 1867 illustrée ).

ments and models of Ferdinand de Lesseps's work on the Suez Canal, then under construction, as well as the geography and the natural history of the site (Figs. 22–23).

In 6,000 square meters, a "condensed and miniature Egypt" was presented to the world, a "brilliant, splendid" achievement, in the eyes of the general commissary to the Egyptian exposition, and one that "revealed [Egypt's] past grandeur and its present richness."[10] The effort was applauded by the West. One French journalist, for example, argued that no other country had understood the idea of a universal exhibition as well as Egypt, which displayed its

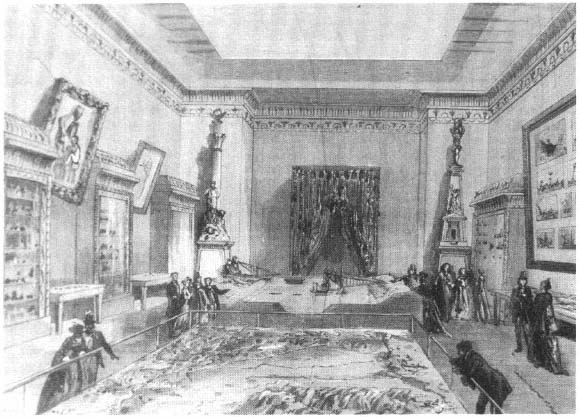

Figure 23.

Interior of the Suez pavillon, showing models of the canal area, Paris, 1867 ( L'Exposition universelle de

1867 illustrée ).

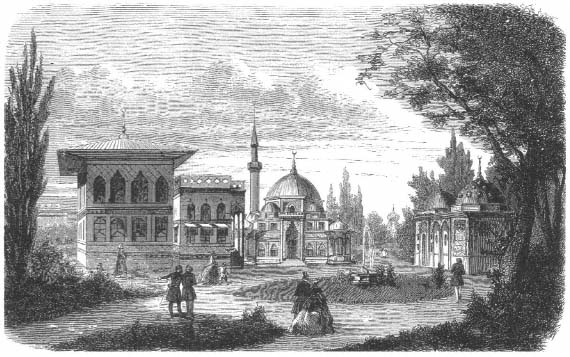

Figure 24.

The Turkish quarter, view (from left to right) of the Pavillon du Bosphore,

the mosque, the fountain, and the bath, Paris, 1867 ( L'Illustration, 2 March 1867).

past and its present.[11] Hippolyte Gautier praised the Egyptian quarter as "not only one of the most sumptuous, but also the most complete and the most instructive."[12]

The Egyptian exhibition had attempted to encapsulate Egypt's history. The Ottoman Empire, in contrast, condensed its cultural and social life in a selection of building types. The Ottoman section, designed by Léon Parvillée, was composed of three buildings—a mosque, a residential structure called the Pavilion du Bosphore, and a bath—around a loosely defined open space. In the center of this space was a fountain (Fig. 24). The mosque represented the religious sphere; the Pavilion du Bosphore, the homefront; the bath, social and cultural ritual; and the fountain, the public sphere. On the occasion of Sultan Abdülaziz's visit, a triumphal gate to the quarter was erected; with its formal

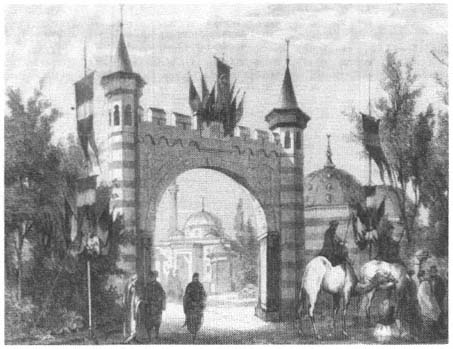

Figure 25.

Gateway to the Turkish quarter, Paris, 1867 ( L'Exposition universelle de 1867 illustrée ).

references to the gates leading to the different courts of the Topkapi Palace and its imperial tugra , "sultan's seal," it symbolized the imperial presence (Fig. 25).

Like that of the Egyptian section, the layout of the Turkish quarter was deliberately irregular, even though the basic premise—a square open space with a fountain in the center, surrounded by buildings with symmetrical facades—did not call for it. This arrangement was derived not from Turkish precedent but from French academicism. The idea was to create by irregularity an "authentic" and "picturesque appearance."[13]

Not far from the Egyptian-Ottoman complex was another Islamic section, composed of the Tunisian and Moroccan exhibitions (Fig. 26). Perhaps because of their associations with bedouin culture, both had tents for the display of products. Tunisia also had a residential structure, called the Palace of the Bey

Figure 26.

Tunisian palace, Moroccan tent, and Moroccan stables, Paris, 1867 ( L'Exposition universelle de 1867 illustrée ).

because the bey of Tunisia had stopped there briefly during his visit to Paris. The two domes of this palace and the tents created an Islamic skyline. Strolling from the Quai d'Orsay toward the main exhibition hall, a visitor would see first these domes and tents and then the domes and minarets of the Egyptian and Ottoman parks. Hippolyte Gautier called the entire section the Quartier Oriental:

The entire Orient is before you; do not look for machines here, or for the practical inventions of the human mind; you are in the domain of contemplative life: the agreeable precedes the utilitarian, and poetry is intricately mixed into the smallest detail of existence.[14]

People dressed in colorful local costumes, Middle Eastern music coming from the pavilions, and the aromas of local cuisines from the cafés gave the quarter the real flavor of the Orient. According to one observer, "the illusion was complete. . . . To see the Orient . . . it is enough to get on the omnibus."[15]

Universal Exposition of 1873, Vienna

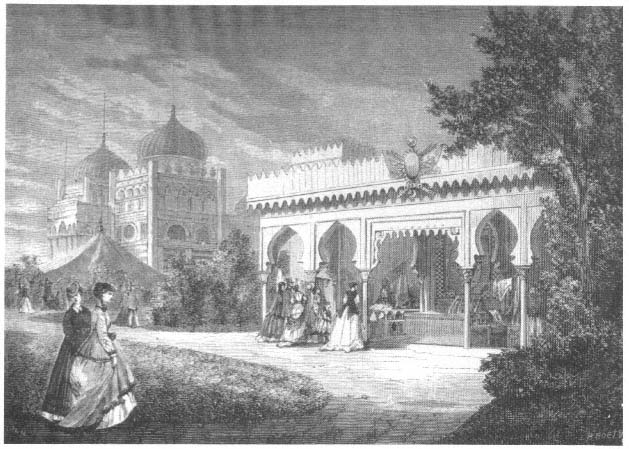

The precedent set by the Ottoman and Egyptian quarters at the 1867 exposition determined the format in Vienna six years later. The main exposition building was a longitudinal structure with a domed central section. The Ottoman and Egyptian pavilions were in the southeastern part of the park in front of the main hall (Fig. 27). Once again picturesque landscaping brought the two displays into relation and created an Islamic village on the periphery of the fairgrounds.

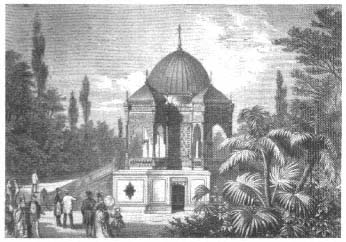

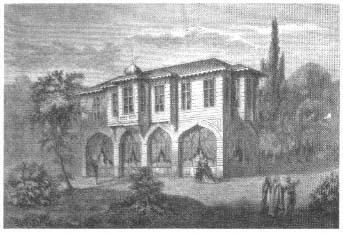

The Ottoman quarter consisted of seven small structures: a main pavilion carefully duplicating the Sultan Ahmed Fountain (1728) in Istanbul and presenting it as an example of Ottoman architecture (see Fig. 66); a high domed pavilion, the Sultan's Treasury, where valuable items such as jewelry were displayed (Fig. 28); a residential structure based on the Yali Kösk in Istanbul and reminiscent of the Pavilion du Bosphore of 1867; a bath, along the lines of Parvillée's bath in 1867; a café (Fig. 29), and a small two-story building with a bazaar on the first floor and residential apartments on the second floor (Fig. 30).[16] Whereas all the Ottoman buildings in 1867 were designed according to a set of clear principles that followed historic references, here the main pavilions quoted monuments, and the commercial structures interpreted vernacular traditions.

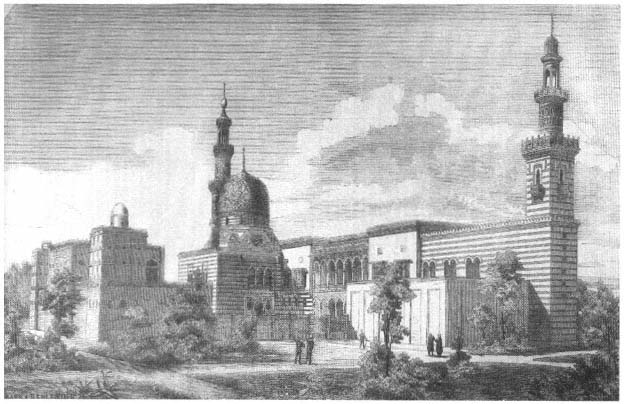

Unlike the Ottoman section, the Egyptian section consisted of a single building, composed of several distinct parts (Fig. 31). The dominant feature was a pavilion that duplicated the funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay in Cairo from the late Mamluk period (1470s), its minaret and dome carved in arabesques and star patterns. A second minaret, with a square base, possibly inspired by the minarets of the mausoleums of Salar and Sanjar al-Jawli from the early Mamluk period (1300s), marked the other end of the structure. The eclectic styles in between enhanced the impression of a street facade rather than suggesting a single building. As in the Ottoman section, the structure referred to both the monumental and the vernacular.

Figure 27.

The Ottoman section, with (left) the main exhibition hall and (background)

the Egyptian buildings, Vienna, 1873 (L'Esposizione universale di Viena, no. 10).

Figure 28.

Sultan's Treasury, Vienna, 1873 (L'Esposizione universale

di Viena, no. 19).

Figure 29.

Turkish café, Vienna, 1873 (L'Exposizione universale

di Viena, no. 36).

Figure 30.

Turkish bazaar, Vienna, 1873 (L'Esposizione universale

di Viena, no. 16).

Figure 31.

Egyptian section, Vienna, 1873 (L'Esposizione universale di Viena, no. 3).

Figure 32.

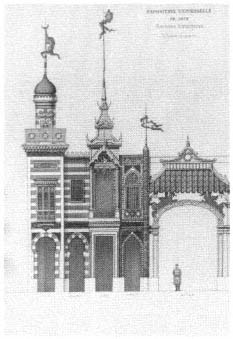

Jacques Drévet's drawing of (from left)

the Tunisian, Morroccan, Siamese, Persian,

and Annam pavilions, Paris, 1878 (Jacques

Drévet, architecte ).

Universal Exposition of 1878, Paris

The desire to bring more order to the peripheries may have led organizers of the 1878 exposition to introduce a new linear arrangement, a Rue des Nations (street of nations), where a series of national pavilions would be erected. Although the facades were to be 5 meters wide, some nations (Belgium, Switzerland, Russia, England, the United States, and Italy) were allowed more width; the pavilions of Morocco, Tunisia, and Persia followed the 5-meter rule.[17] The idea was to create an architectural collage, with each nation represented according to its own taste and tradition. While illustrating the architectural diversity of the entire world in a short span, the street would also raise the issue of "national" architecture. For Hippolyte Gautier and Adrien Desprez, the Rue des Nations was "the most original, the most novel [idea] of the exposition."[18]

Morocco, Tunisia, and Persia were the only Muslim countries represented on the Rue des Nations (Fig. 32).[19] The task of searching for an architecture that would symbolize these Muslim nations (as well as Siam and Annam

Figure 33.

An Oriental bazaar in the Trocadéro Park, Paris, 1878 (Bibliothèque Nationale,

Département des Estampes et de la Photographie).

[Vietnam]) was assigned to Jacques Drévet, a French architect, who had designed the Egyptian quarter in 1867. His ensemble of four facades attracted little attention and was deemed "of no importance and scarcely demanding notice."[20] The Spanish building at the exposition also had an Islamic facade. The structure comprised three sections, the two end pavilions "more sober in style" and the central one adorned with details from the Alhambra and the Great Mosque of Cordoba.[21]

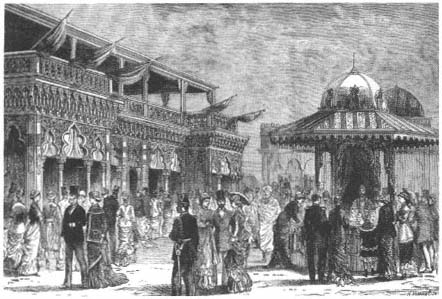

Other Islamic pavilions in 1878 were sited to show their relationship with France. Algeria, France's most important and most turbulent colony; Tunisia, which would become a French colony in just four years; Morocco, which would take another two decades; and Egypt, then under the control of an Anglo-French debt management commission, were all in front of the Trocadéro Palace, representing France, whose arms, like those of a protective father/master encircled these North African nations (Figs. 33–34).

Figure 34.

View of the Trocadéro, with the Islamic quarter at right, Paris, 1878 (Bibliothèque Nationale,

Département des Estampes et de la Photographie).

Universal Exposition of 1889, Paris

Inspired by the Rue des Nations, the 1889 exposition further developed the commercial potential of the street and brought together on it a number of thematically connected displays. Two memorable streets of the fair, the History of Habitation (L'Histoire de l'habitation) and the Cairo Street (Rue du Caire), included Islamic representations, both claiming archaeological and historical accuracy. Neither was merely an open-air museum; as nineteenth-century streets they incorporated urban and commercial life and became places of "spectacle."[22]

The History of Habitation consisted of forty-four dwellings intended to tell the story of "the slow but inevitable march of humanity through the ages."[23]

Located in a longitudinal park along the Seine, these houses contrasted in scale and style with the Eiffel Tower behind them. They were designed by Charles Garnier, renowned perhaps as much for his hostility to the expression of iron structure in buildings as for his Paris Opera. The "palaces, grottoes, tents, villas, cottages, huts, and various shelters forming the Exposition of Human Habitation" voiced tectonically Garnier's protest against Eiffel's work.[24] Ironically, their location at the foot of the tower brought them to the forefront of the fair. The siting was particularly fortunate, because Garnier intended them as an architecture of spectacle, "a moving panorama, where all habitations parade before us."[25]

The houses were presented in two main categories: prehistorical and historical. In the first group were natural habitats (in the open air, in sheltering woods, in rocks and grottoes) as well as some simple structures; in the second group were the structures of "primitive civilizations" (e.g., Egyptian, Assyrian, Phoenician), civilizations arising from Aryan invasion (e.g., Hindu, Persian, German, Gallic, Greek, and Roman), and, finally, "contemporary [versions] of primitive civilizations"—those that "did not exert any influence on the general advance of humanity" (e.g., Chinese, Japanese, Eskimo, Indian, Aztec, Inca, and African).[26] Although presented as a historical survey, the display featured anthropological and ethnographic elements: the dwellings were decorated in "typical" ways, and a "native" in authentic costume welcomed visitors.[27] Furthermore, it included contemporary civilizations other than Western, thereby adhering to the definition of anthropology as the study of societies considered spatially and temporally distant.[28]

Garnier did not consider his survey complete; he thought of the entire display as a "scenario," with several stars and a supporting cast. He insisted, however, that the dwellings themselves were historically accurate, that they reflected a "general type" based on a synthesis of crucial elements. He argued that in them "the resemblance to truth was truer than truth itself" (le vraisemblable est bien plus vrai que la verité ).[29]

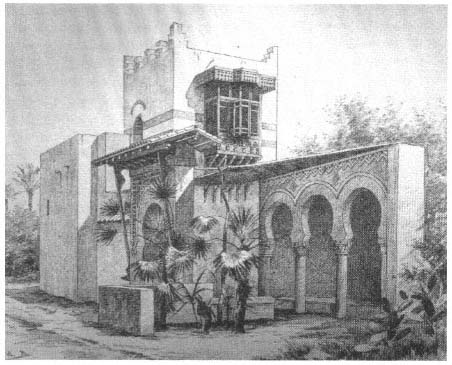

The History of Habitation included two Islamic houses, an Arab and a Sudanese (Figs. 35–36). Working in collaboration with a historian, A. Ammann, Garnier produced a book that presented a scholarly basis for the houses displayed at the exposition. The goal was to trace the development, the marche en avant, of the human habitat; Garnier and Ammann argued that the Muslim house offered little to this development because "Mohammadism sterilized all the regions it invaded."[30]

Basing their findings on travelers' accounts of Arabia, the authors declared that the Arab house had not changed over time; in its overall simplicity, it resembled the nomad's tent and consisted of women's quarters, men's quarters, and outbuildings. Rooms were either square or rectangular, and courtyards were essential. In its ornamentation, however, the Arab house in the most splendid period of Arab history, the eighth and the ninth centuries, was remarkable. In houses of this period horseshoe arches were supported by elegant colonettes; arabesques were important decorative motifs, and brilliant colors

Figure 35.

Arab house, Paris, 1889 (Garnier and Ammann, L'Habitation humaine ).

were used.[31] The authors described Muslim life as they knew it from literature and painting: "The ideal of happy life consisted of resting lazily in a cool place, surrounded by exquisite light and forms. Oriental life flowed, softly and voluptuously, behind these walls burning in the sun."[32]

Emphasizing that the Muslim house "had played no direct role in the grand architectural revolution of the Renaissance," Garnier displayed only two examples. The Arab house consisted of cubical masses enlivened with musharabiyyas (lattice woodwork on the windows) and an arcaded courtyard with horseshoe arches. To give a complete view of the design to passersby, only half of the courtyard was built. The Sudanese house, even simpler, was a rectangular structure with walls from 2 to 2.50 meters high; its only opening to the exterior was a small door.[33]

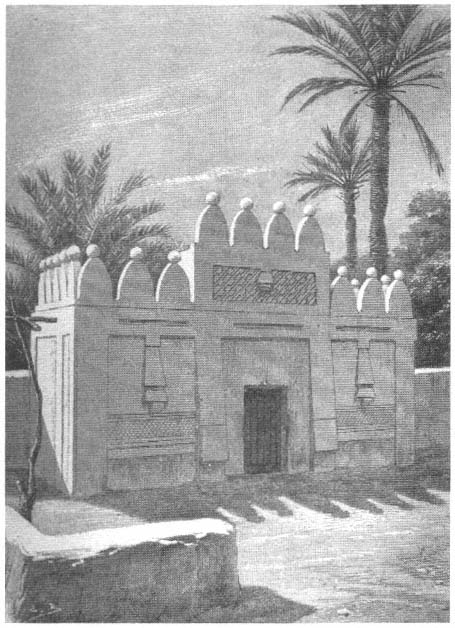

Figure 36.

Sudanese house, Paris, 1889 (Garnier and Ammann, L'Habitation humaine ).

Garnier understood Islamic culture as one that was fixed in history and was not a valuable resource for modern civilization. He argued that the salvation of Islamic architecture would be achieved by colonization: "the French conquest has just begun . . . to change [the] antique physiognomy" of Algerian, Tunisian, and Moroccan architecture.[34]

Although Garnier presented the History of Habitation as an educational display, it was not necessarily received as such. The critics, by now familiar with the "authentic" representations of previous fairs, claimed Garnier's pavilions were not based on reliable documents but only on the architect's imagination. They argued that the result was "absolutely fanciful" and did not convey the "impression of truth and of life." The dwellings were "children's toys without any scientific utility." Furthermore, they were located randomly, "Oriental architecture next to European, only to daze the visitor."[35]

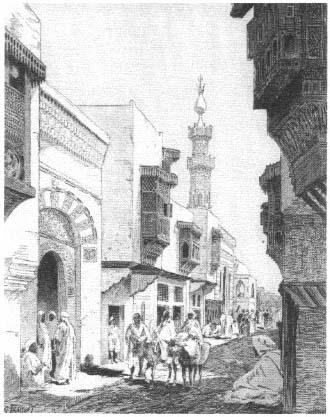

Like the History of Habitation, the Rue du Caire vacillated between archaeological ambitions and the desire for spectacle. Its author Delort de Gleon, according to some sources, was a wealthy Frenchman who had lived in Egypt for about twenty-five years and was willing to pay for the exhibit.[36] The title page of the booklet Gleon wrote on the Rue du Caire, La Rue du Caire à l'Exposition universelle de 1889, describes him as the "architect and general commissioner of the Egyptian section." Although Charles de Lesseps was nominated president of the committee, Gleon told his readers that Lesseps gave him carte blanche to create the Egyptian section.[37]

Delort de Gleon collaborated with a young architect named Gillet. Using recycled architectural fragments (musharabiyya s, window and door details, decorative details, etc.) from demolished buildings in Cairo, the two men created a neighborhood street of twenty-five houses, representing different periods and styles of Cairene residential architecture (Fig. 37).[38] Gleon's stated goal was to gather "various motifs from all belles époques " of Cairo's history.[39] To complete the Cairene atmosphere, he integrated a religious monument into the street, a reduced copy of the Sultan Qaytbay complex, which he declared "the most gracious monument" of Cairene architecture,[40] with its minaret, dome, and surface details that added picturesqueness to the perspective.[41] Inside, the mosque was richly decorated with marble-covered walls, ceiling patterns highlighted in gold, and delicate woodwork.[42]

Figure 37.

Rue du Caire, Paris, 1889 (Bibliothèque Nationale,

Département des Estampes et de la Photographie).

Although he insisted on the authenticity of his representation, Gleon diverged from Cairene models in making the street wider than a typical Arab street (to allow the railroad to pass through) and in keeping building heights (including that of the minaret) lower because of construction problems. Otherwise, the buildings were "absolutely exact" and "faithfully reproduced."[43] In fact, the Rue du Caire on the Champ de Mars was more authentic than the streets in Cairo itself, because, Gleon argued, it was impossible to find an untouched old street in Cairo. The old houses with musharabiyya s no longer abutted each other, but were "separated, alas, by modern houses in bad taste!" Collectors now salvaged beautiful parts from the old buildings of Cairo.[44]

Figure 38.

Donkey drivers on the Rue du Caire, Paris, 1889 ( Revue de l'Exposition universelle de 1889, vol. 1).

Many visitors to the exposition, Egyptians and Europeans alike, admired the local color of this street. Hippolyte Gautier was fascinated by the "authentic pieces . . . picked by a collector of great taste, by a real artist."[45] An Egyptian visitor noted that "even the paint on the buildings was made to look dirty."[46] A French observer agreed: "You are in Cairo; a winding and picturesque street opens in front of you, with its musharabiyya s, its ingenious wood lattices, . . . its balconies projecting on the street."[47]

The "spectacle" of the street—the musicians, male and female dancers, artisans, and donkey drivers who crowded it—was intended to contribute archaeological exactitude (Fig. 38).[48] That commerce and entertainment overshadowed

Figure 39.

Esplanade des Invalides, site plan, Paris, 1889 (Alphand, Exposition universelle internationale

de 1889 à Paris ).

Gleon's concern for accuracy is illustrated by the mosque. Muhammad Amin Fikri, an Egyptian visitor, noted in disgust: "Its external form as a mosque was all that there was. As for the interior, it had been set up as a coffeehouse, where Egyptian girls performed dances with young males, and dervishes whirled."[49]

The 1889 exposition turned out to be a national celebration for France rather than an international event like earlier expositions. Because it celebrated the centennial of the French Revolution, many governments (among them that of the Ottoman Empire) declined to participate, as a protest against the ideals of the revolution.[50] Undeterred, France proceeded to display its power in a grandiose manner, as illustrated, for example, by the huge platform dedicated to its colonial possessions. Both "to convey a real idea of the economic state of [France's] diverse possessions overseas" and to show the nation to the subject people, the French organized the Esplanade des Invalides between the Quai d'Orsay and the Rue de Grenelle as a "striking display" of "original buildings" and artifacts (Fig. 39). The Algerian and Tunisian palaces occupied a prominent location at the entrance to the esplanade from the embankment. Behind

Figure 40.

Gate of the Tunisian

souk on the Esplanade

des Invalides, Paris,

1889 (Monod, L'Exposition

universelle de 1889, vol. 2).

Figure 41.

Markets on the Esplanade des Invalides, Paris, 1889 ( Revue de l'Exposition

universelle de 1889, vol. 2).

them souks, cafés, and restaurants clustered, complete with a replica of a Kabyle village and bedouin tents (Figs. 40–41).[51] A crowd of "[indigenous] people of all races, all colors, and all classes" filled the winding streets of the

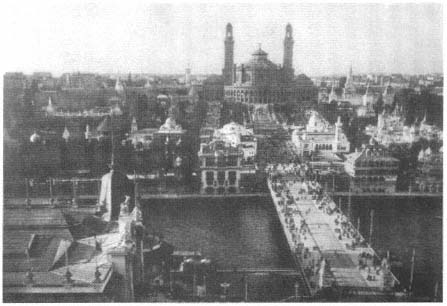

Figure 42.

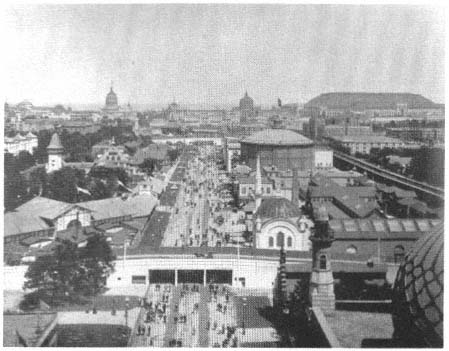

Aerial view of the Chicago exposition, 1893 ( Rand, McNally and Co.'s Pictorial

Chicago and the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893).

esplanade, their diversity creating "a profound impression of the grandeur [of France]." Here the colonized, dazzled by French civilization, could understand the privilege of being part of it.[52]

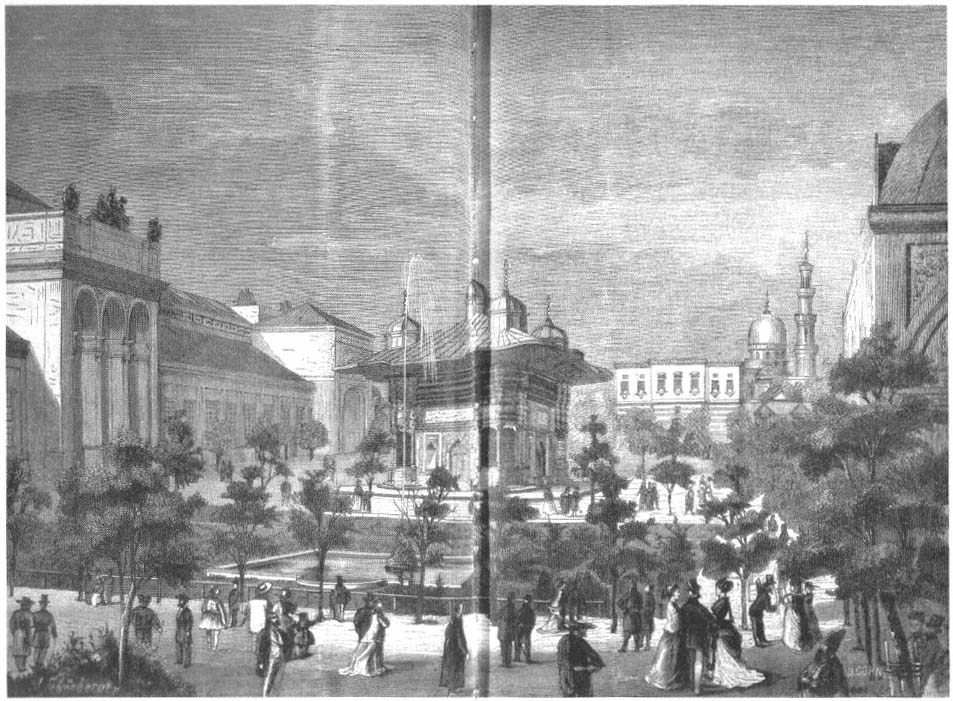

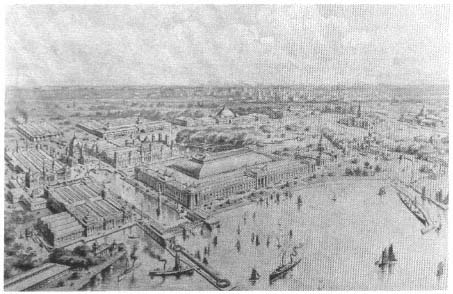

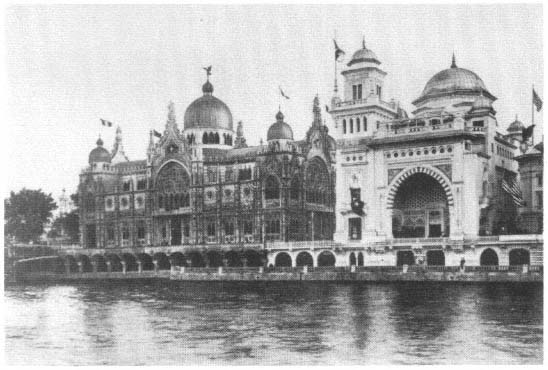

World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Chicago

The contrast between the academic planning of the main exhibition and the deliberate haphazardness of the periphery was perhaps nowhere as striking as at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago (Fig. 42). The World's Fair, as it was commonly called, was a turning point in the history of American architecture. Under the supervision of Daniel Burnham, Jackson Park on the Chicago waterfront was developed into a "dream city," the forerunner of the City Beautiful movement. Burnham had appealed to the par-

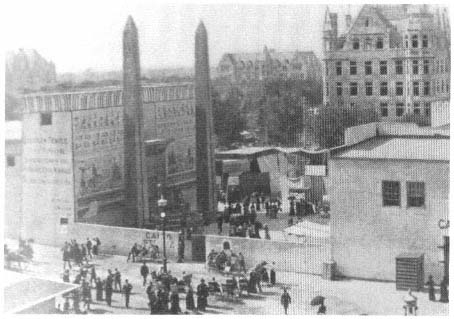

Figure 43.

View of the Midway from the Ferris wheel: (right) the Ottoman quarter, with the

mosque at its entrance, and, next to it, the Egyptian section with obelisks,

Chicago, 1893 (The Dream City, vol. 1).

ticipating architects for uniformity of design—to be achieved by the use of the classical style. Here was a mode in which the leading American architects of the late nineteenth century, most of them trained in the Beaux-Arts system, felt at ease. With the collaboration of the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, the "White City" was created, with its lagoons, long axes and vistas, and white classical monuments. The scale was large, and the exhibition was the most complete urban-scale project realized since the planning of Paris and Vienna in the 1860s.

The concern for uniformity in urban design and architecture seemed to disintegrate beyond the main sections on the waterfront. The exotic missions were placed along the Midway Plaisance, an avenue six hundred feet wide that extended for a mile west of the Women's Building (Fig. 43). There was, however, an order in the site plan of the seemingly chaotic national villages.

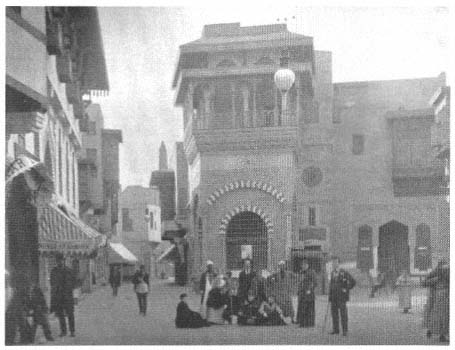

Figure 44.

Entrarce to the Egyptian quarter, Chicago, 1893 (Rossiter, A History of the

World's Columbian Exposition, vol. 2).

Figure 45.

Cairo Street, Chicago, 1893 (World's Columbian Exposition, vol. 2).

According to a contemporary literary critic, Danton Snider, the Midway was organized as a "sliding scale of humanity. The Teutonic and Celtic races were placed nearest to the White City; farther away was the Islamic world, East and West Africa; at the farthest end were the savage races, the African Dahomey and the North American Indian."[53] The Committee on Ways and Means had decided in advance that the Midway would have an "ethnological and historical significance" and thus some scientific respectability.[54] Echoing the Rue des Nations theme, the committee specified that here

the style of architecture in each case . . . be characteristic of the country represented. It will thus be seen that in addition to the beautiful buildings erected by the Exposition there will also be a grand display of architecture from every part of the world, making the variety of design so extensive as to be bewildering in its outlines.[55]

Thus the indispensable Cairo Street put on its show in Chicago (Fig. 44). Its facade on the Midway had "nothing artistic" about it; passersby had no clue to the life of the street from the plastered exterior wall. But once inside the gate, visitors saw a lively array of shops and houses, a café, the "solemn spectacle" of a mosque,[56] two obelisks, a "Temple of Luxor," and a much talked-about theater where the belly dance was performed.[57] The street itself was "just as crooked as one has a right to expect in a Cairo thoroughfare" (Figs. 45–46). A Chicago Tribune reporter argued that the Egyptian quarter had the "picturesque beauty and strangeness of 'Masr-al-Kahia,' as the natives termed the famous city, which stands near the site of old Babylon." The picturesqueness was enhanced by the projecting upper levels of the buildings:

Beautiful balconies and bow windows are seen, while here and there relief is given by a carved balcony. All the windows are protected by graceful woodwork and many of them are made of stained glass. The shades in the windows are attractive. No paint covers the closely-woven Meshrebieh screens which protect them.[58]

As in Delort de Gleon's Rue du Caire, the materials were shipped from Egypt "in order that Cairo street scenes may be represented,"[59] and consequently the buildings enjoyed "a polish and color that only age could bring."[60]

Figure 46.

Cairo Street, Chicago, 1893 (The Dream City, vol. 1).

The authenticity of the architectural, as well as the social, reproduction pleased many:

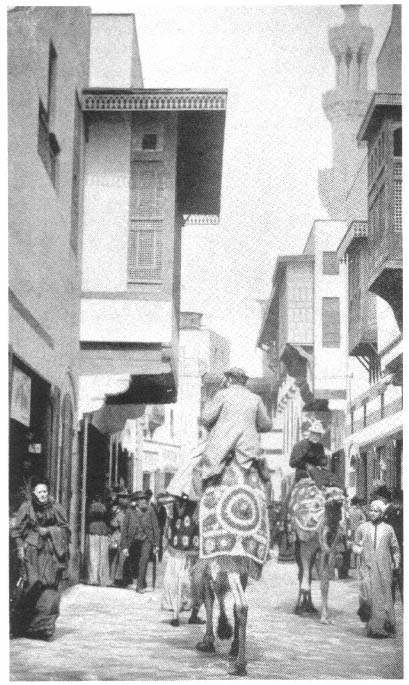

Architecturally, the street, long and winding, was perfectly reproduced; the shops were real shops, not mere exhibits, and it required only American money and a kind of polyglot French to strike a bargain. The attendants were Egyptians; and real citizens of Cairo lived in the upper stories of the houses, and loitered or hurried through the street, touching, jostling the cosmopolitan sightseers, who alone seemed foreign here. Donkeys and camels were steeds and vehicles. . . . From an open door came the music of an Oriental theater, and from a balcony hung a girl of sunny Egypt, . . . [and] barefoot babies played around the doorsteps or joined the motley throng that watched an Egyptian juggler on the corner; with a clanking of gilded chains and trapping, a band of pilgrims, camel-mounted, returned from Mecca; or preceded by a waving sword and escorted by many guests, a bride rode camelback to the temple: and up and down the throughfare and in and out of mysterious dark passages moved . . . the normal life of the Egyptian settlement.[61]

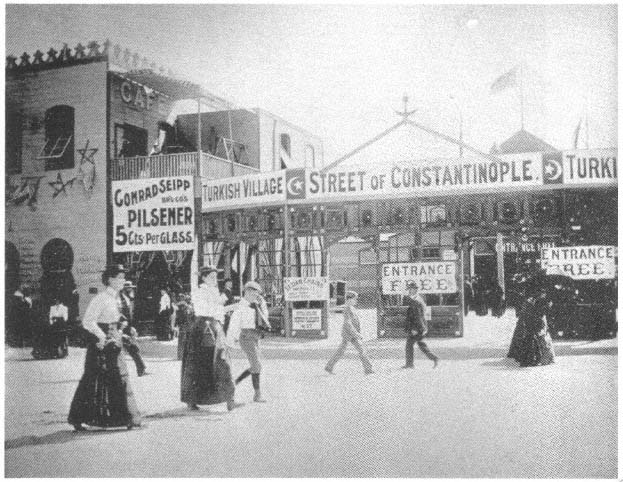

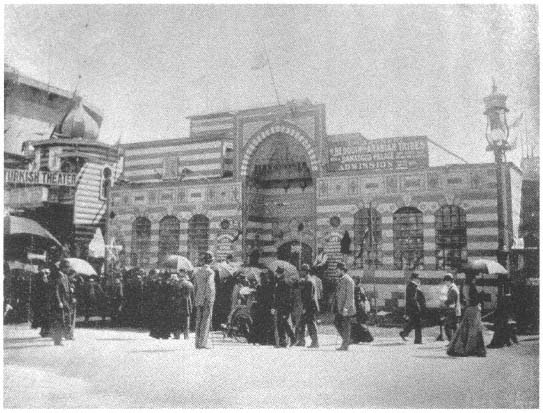

A mosque announced the Ottoman presence on the Midway (see Fig. 43), recalling its more elaborate 1867 counterpart in Paris. The high dome and minaret made the mosque one of the symbols of the Midway while helping to define the entrance to the Turkish Village. The village, also referred to as the Business Street of Constantinople, was designed to recall the Byzantine Hippodrome in the Ottoman capital (Fig. 47). The outstanding feature was an obelisk, a wooden replica of the Egyptian obelisk on the Hippodrome in Istanbul, whose lettering had been transferred to plaster casts, carved on the site in Turkey, and shipped to Chicago in sections. A low balustrade, like that around the original, protected the replica.[62] This was the first display at an exposition of Istanbul's Byzantine past as part of Ottoman culture—it had been added, perhaps, because the Egyptian displays, as well as the Tunisian and Algerian pavilions, included material on ancient history. The Hippodrome, however, was not simply meant as a cultural symbol; it included a track for horse races, and it also served as an entertainment center, where visitors could watch "fantasias and exercises by a number of dromedaries, harnessed and caparisoned according to Arabic fashion." The Arab horses and dromedaries were chosen from the best breeds and shipped to Chicago.[63]

Figure 47.

Entrance to the Street of Constantinopole, Chicago, 1893 ( Glimpses of the World's Fair ).

Figure 48.

Damascus palace, Chicago, 1893 (Glimpses of the World's Fair ).

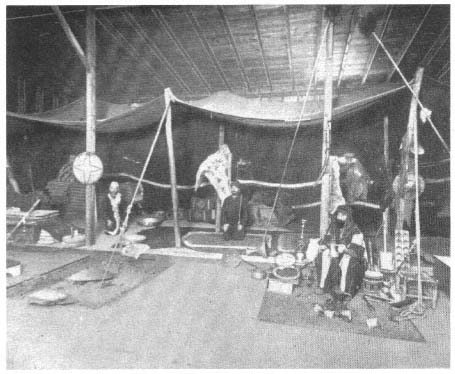

At the center of the village was a Turkish restaurant in a cubical building with a three-tiered facade and overhanging cave that was topped by a small dome. In its overall form and architectural features, this structure repeated the themes of the main Ottoman pavilion in Jackson Park. The rest of the street was lined with shops; there was also a Turkish theater as well as a fortune-teller's tent in front of the obelisk.[64] In the Turkish Village and adjoining the theater, the city of Damascus was represented by a pavilion called the Palace of Damascus, and by an encampment (Figs. 48–49). The palace's large single

Figure 49.

"Camp of Damascus colony," Chicago, 1893 ( World's Columbian Exposition, vol. 2).

room was richly decorated, with a wide divan all around, and in its marble-paved vestibule was an octagonal fountain. Photographs representing Syrian tribal life and characteristic landscapes hung on the walls. In addition to performances in the theater, an "Oriental wedding ceremony" was acted out daily in the palace, complementing the performances in the theater.[65]

The Universal Exposition of 1900, Paris

The 1900 "exposition of the century," like the 1878 exhibition, had a street of nations but at a more visible location (Fig. 50). The Street of Nations now occupied the Quai d'Orsay between the Pont des Invalides and the Pont de l'Alma, the bridges connecting the two principal sections of the exhibition, the Champ de Mars-Trocadéro and the Esplanade des Invalides-Avenue Nicolas II

Figure 50.

Rue des Nations, with Ottoman pavilion to the right, Paris, 1900 (Bibliothèque Nationale,

Département des Estampes et de la Photographie).

along the waterfront. Nations considered more important were given larger sites facing both the river and the street.

The allocation of space to Islamic countries in the 1900 exposition made evident a hierarchical classification. The Ottoman Empire and Persia, both sovereign nations, had their pavilions on the Rue des Nations. The Ottoman Empire, perceived as more important politically, also faced the embankment and was located between the pavilions of Italy and the United States, whereas Persia's much smaller pavilion sat on the back row, between Peru and Luxembourg. Egypt, now accepted as a British colony, was with the other colonies in the Trocadéro Park.

Figure 51.

View toward the Trocadéro Palace, with (foreground) the Iéna Bridge, (right)

the Algerian palace, and (left) the Tunisian palace, Paris, 1900 ( Exposition

universelle internationale de 1900, vues photographiques, Paris, 1900).

The displays of the Ottoman Empire and Persia were confined each to a single building. Egypt still had its temple, bazaar, and theater, but this time in a single three-part structure. Now it was the French colonies of North Africa that represented the full exotica of the Muslim world. The palaces of the two important colonies, Algeria and Tunisia, were in the Trocadéro Park, on the main avenue bisecting the park itself and the Champ de Mars and connecting the Trocadéro Palace to the Eiffel Tower via the Iéna Bridge. Viewed from the Iéna Bridge, with the Trocadéro Palace behind them, they helped to define the axis of the exposition grounds and complemented the larger palace stylistically with their Islamic references (Figs. 51–52). Seen from the palace, with the Eiffel Tower in the background, their white stucco masses and their facades abstracted from various precolonial monuments contrasted with the engineering aesthetics of the tower, thus juxtaposing the industrial progress of the empire and the timelessness of its colonies (Fig. 53). The juxtaposition offered a visual symbol of the French colonial tactics of assimilation and contrast.[66]

The Algerian Palace, given the "place of honor" in the Trocadéro Park, was a "symmetrical and coherent" building.[67] Inside, however, was an entire Rue

Figure 52.

View of the Trocadéro Park with (center foreground) the Algerian palace, (lower left)

the Tunisian palace, and (background) the Trocadéro Palace, Paris, 1900

(Bibliothèque Nationale, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie).

Figure 53.

View toward the Eiffel Tower from the Trocadéro Park, with (right) the

Tunisian palace and (left) the Algerian palace, Paris, 1900 ( Figaro

illustré, no. 124, July 1900).

Figure 54.

Rue d'Alger, Paris, 1900 (Bibliothèque

Nationale, Département des Estampes

et de la Photographie).

d'Alger, winding picturesquely, replete with two-story houses with projecting second stories, musharabiyya s, decorated doorways, and shops on the street level.[68] It was considered "a faithful reproduction of one of those tortuous streets" (Fig. 54).[69]

The Tunisian exposition was next to the Algerian village, and the entire complex was called the Ville Arabe. It was an agglomeration of architecture from Tunisia: a replica of a fountain from the Rue Sadun in Tunis, a minaret from the Great Mosque of Sfax, a copy of the Mosque of Sidi-Maklouf from Kef, a zawiya (Sufi convent) from the Casbah Square in Tunis, the Bab al-Jadid gate from the walls of Tunis, and another old town gate from Soussa—all surrounding a large court. The main pavilion was a model of the Mosque of Sidi Mahres in Tunis. In sum, this village represented "all the towns of Tunisia."

The pieces were integrated by vaulted picturesque passageways and irregular streets, all designed "as though by chance." One observer remarked:

One could swear that these buildings are inhabited; the angles are rounded, the rough-cast broken, the tiles frosted—this imperceptible steam which represents time—and the stones, skillfully made up, display the superb reddish color of limestone in the countries loved by the sun.[70]

The appeal to the senses was complete. Even the smells were authentic. Here one could "breathe the smell of Africa," one Frenchman noted, "and for us, the colonizers, the smell of Africa is delicious."[71]

Although a concern for authenticity continued to inform the architectural representation of the French colonies, a new interest in symmetry emerged in 1900, with the result that the picturesqueness was hidden behind uniform screens or regularized along an axis. The enclosing of the Rue d'Alger clearly manifested the first tendency; the site plan of the Tunisian quarter revealed the second: the pavilions of the "village" were placed axially and symmetrically around a central open space. Furthermore, the entire Tunisian section was neatly hidden behind "regular facades, meeting at right angles."[72]

The 1900 Paris exposition expressed changing attitudes about French architecture. The 1889 exposition celebrated great engineering achievements, whereas the two major buildings of the 1900 exposition, the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais, returned to the vocabulary of "high art." Charles Girault, the architect of these buildings, which were intended as permanent structures, used modern engineering techniques and materials but clad the facades in classical masonry.[73] Undoubtedly, the classical architecture of the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago was influential in this change. Along with the return to classicism, a stricter control was exercised in planning the fairgrounds in 1900, and picturesque effects were minimized. Although the buildings on the Rue des Nations were designed in many different styles, they were neatly aligned and their regularized siting complemented the symmetry and axiality across the river. Moreover, in the turn-of-the-century exhibition, the haphazardness of the indigenous villages was tactfully hidden from immediate view.

After four decades, the Islamic world no longer seemed exotic. Islamic nations' displays at the international fairs had entertained Westerners and had taken them to distant lands, nurturing their imaginations by offering them unknown sights, images, foods, drinks, music, and dance. At the fairs, the Orient that European writers, scholars, and artists had defined and described (in Edward Said's word, "constructed") since at least the beginning of the nineteenth century was presented as a three-dimensional living model. Thus it was brought to the West and incorporated into Western culture. Moreover, with the expansion of colonial territories, the exotic increasingly belonged to the Western powers.