10

Elaborating on the Established Mode of Representation: 1905-1907

Between December 1905 and May 1907, filmmaking practice at the Edison Manufacturing Company changed very little even as motion picture exhibition was undergoing a fundamental upheaval. As before, there were two production units. One was headed by the solitary, itinerant cameraman Robert K. Bonine, who toured the United States and its possessions, taking travel subjects as well as some news films and industrials. While the cameraman system was used for actualities, a collaborative system of production remained in effect at the studio as Edwin Porter and Wallace McCutcheon continued to explore the rich possibilities of cinema within the already established representational system of fiction film. With the nickelodeon era beginning, the Kinetograph Department enjoyed enhanced profitability and spent more time working on each subject. That this response to the proliferation of storefront motion picture theaters was commercially inappropriate is evident from a brief look at the emerging new era of exhibition.

A Transformation in the Realm of Exhibition

The rapid proliferation of specialized storefront moving picture theaters— commonly known as nickelodeons (a reference to the customary admission charge of five cents)—created a revolution in screen entertainment. In retrospect the ten-year period between 1895 and 1905 witnessed the establishment and finally the saturation of cinema within preexisting venues. Reviewing vaudeville in late 1905, the new publication Variety declared that "in the present day when a special train is hired and a branch railroad tied up for a set of train robbery or wrecking pictures, the offerings are really excellent and those who remain

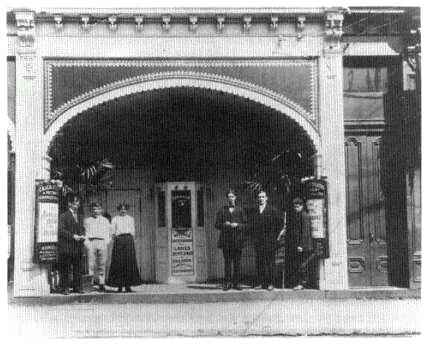

Early nickelodeon theaters such as this one transformed the film world.

and watch them, get sometimes what is really the best thing on the bill. The picture machine is here to stay as long as a change of film may be had every week."[1] Regular Sunday motion picture shows were being given in many eastern cities, and traveling motion picture exhibitors prospered and increased in numbers. Penny arcades and summer parks boasted of numerous picture shows by 1904-5. Such success pointed to the potential viability of specialized picture houses.

Nickelodeons transformed and superseded these earlier methods of film exhibition. They were more than simply specialized motion picture theaters—a common, if often ignored, venue for film exhibition since 1895. The new exhibition mode was made possible by a large and growing, predominantly working-class, audience; the existence of rental exchanges, which facilitated a rapid turnover of films; the conception of the film program as an interchangeable commodity (the reel[s] of film); a "continuous" exhibition format; a sufficient level of feature production to meet demand for frequent program changes; and the relative independence of film exhibition from more traditional forms of entertainment. The nickelodeon phenomenon developed first in the urban, industrial cities of the Midwest, beginning in Pittsburgh, where Harry

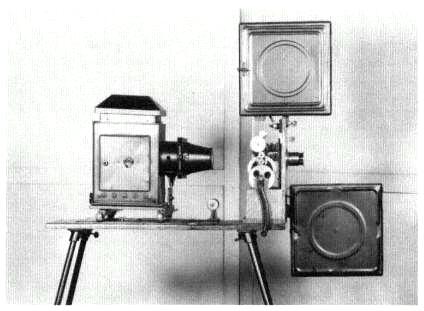

An Edison Exhibition Projecting Kinetoscope, ca. 1907-8.

Davis opened his first Pittsburgh storefront theater in June.[2] With the area's working classes enjoying unprecedentedly high wages, Davis's experiment was a success and was quickly imitated in Pittsburgh, Chicago, Philadelphia, and elsewhere. The "nickel madness" of motion pictures spread outward from its midwestern, urban base in an uneven pattern, taking almost two years to reach all parts of the United States.

Although nickel theaters were being recognized as important exhibition outlets by early 1906, New York City, the nation's production capital, did not feel their presence until that spring.[3] Within six months New York was assumed to have "more moving picture shows than any city in the country."[4] In Manhattan the largest concentration was on Park Row and the Bowery, where at least two dozen picture shows and as many arcades were scattered down a mile-long strip. Their principal patrons were Jewish and Italian working-class immigrants.[5] While these groups made up the hard-core moviegoers, middle-class shoppers from the Upper East and Upper West sides helped to support the theaters along Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. When members of the elite or leisure class saw films, they did so at travel lectures like those given by Burton Holmes or at vaudeville performances, not in dingy storefronts.

As newspaper editorials soon made clear, the "better classes" viewed the nickelodeons with contempt and alarm.[6] The sense of farce and anarchistic play

in the comedies and the condemnation of the rich, not only in social message films like The Kleptomaniac but in more conventional melodramas, could be reinterpreted in ways that might threaten the status quo. Both the appeal to sexual desire and pleasure and the depiction of violent and transgressive acts (robbery, murder) encountered strong condemnation from conservative religious groups. Moreover, nickelodeons facilitated ideological slippages or disjunctions in the reception of films: audiences tended to appropriate pictures for their own purposes, which were often quite different than those intended by the filmmakers and production companies.

Nickelodeons created "the moviegoer"—a new kind of spectator who did not view the pictures in vaudeville formats, as one of many offerings at the local opera house, or as part of an outing to the summer park. To attract these often devoted patrons, storefront theaters found it profitable to change their offerings with increasing frequency. New programs were being offered twice a week in July 1905, and three changes each week were becoming common by late 1906.[7] During the following year, many nickelodeons began to change programs every day but Sunday.[8] The lateral expansion of motion picture houses across the country and this vertical increasing frequency of changing programs caused a tremendous demand for films.

Immense opportunities were created not only for exhibitors and producers but for film renters, who operated at the interface between production companies and exhibitors. In the historical model offered here, distribution is not seen as a fundamental aspect of cinema's production, like film production, exhibition, and viewing. The point at which film production and exhibition meet, however, becomes of central importance in a capitalist system. It can be likened to a fault line where two tectonic plates confront each other, creating large quantities of energy. Screen history suggests a "law": significant changes in either the mode of exhibition or the mode of film production will create new commercial opportunities at this interface. The nickelodeon boom was a revolution in exhibition on an unprecedented scale. Those who took advantage of this golden, fleeting opportunity were to later control the industry—William Fox, Marcus Loew, Carl Laemmle, and the Warner brothers. The rise of a new generation of film exchanges proved to be a crucial moment in the industry's history.

Chicago became the first and largest center for new film exchanges. Eugene Cline, Max Lewis's Chicago Film Exchange, and Robert Bachman's 20th Century Optiscope had become active film renters by 1905.[9] They were joined by William Swanson in the spring of 1906.[10] William Selig, who did not enter the rental business himself, aided Swanson financially. Carl Laemmle became unhappy with the high-handed treatment he received when renting films for his two Chicago theaters in mid 1906.[11] Rather than open more nickelodeons, Laemmle started his own exchange in October and attracted customers by of-

fering "service" as well as a reel of film.[12] The film rental business in New York was at least six months behind Chicago. The new generation of exchanges did not appear until early 1907. Nickelodeon manager William Fox, for example, only opened his Greater New York Film Rental Company in March 190.[13] Increasingly renters appeared in cities outside the traditional centers of New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

Thriving exchanges were hampered by a shortage of new pictures. When Laemmle listed popular subjects for rent in May 1907, he included some that were almost two years old—for example, Edison's The "White Caps " and The Watermelon Patch .[14] The demand for films encouraged several groups of film veterans to move into production. Vitagraph recognized the shifting realities of exhibition and greatly increased its fiction film production. It began to sell prints of these original subjects to other renters in September 1905.[15] In early January 1907 George Kleine joined with Samuel Long and Frank Marion, both of Biograph, to form the Kalem Company, which was incorporated in May and began to sell films in June.[16] At about the same time, George Spoor, who owned the Kinodrome Film Service and National Film Renting Bureau, joined with Gilbert M. Anderson, who was then directing for William Selig, and formed Essanay.[17] The large demand for film not only created incentives to start new production companies, it benefited established manufacturers such as Edison.

Edison Benefits from the Nickelodeon Craze

The Edison Manufacturing Company derived enormous profits from modest investments as the moving picture shows proliferated: sales of projecting kinetoscopes grew rapidly as new exhibitors purchased equipment. Gross income on equipment, which had increased 42 percent for 1904 and 52 percent for 1905, leaped 131 percent for 1906—to $182,135, with $87,228 profit, and jumped another 130 percent for 1907 to $418,893, with $220,622 profit. The Edison machine was known for its durability; its high quality and popularity owed much to Porter's technical improvements. The pattern for projector sales stood in marked contrast to film sales, which in 1906 grew 64 percent to $191,908, with $96,527 in profit, but stabilized in 1907, edging up only 7 percent to $205,243, with $116,912 profit.[18] The increase in 1906 was achieved by selling more copies of each subject. Not only did the Kinetograph Department fail to respond to mushrooming demand by increasing the production rate of new negatives, the number of new fiction narratives actually declined. During 1906 Porter and McCutcheon produced only ten features that were copyrighted and offered for sale through the Edison organization. The same pace continued into the following year, as only another four features were released onto the open market through July 1907, when Porter and his production staff moved to Edison's new indoor studio in the Bronx.

Sales on a per-film basis approximately doubled in 1906 over the previous

year. The most popular film of 1905, The Whole Dam Family and the Dam Dog , sold 92 prints during the year of its release, but Dream of a Rarebit Fiend sold 192 copies the following year. Other features sold between 52 and 146 copies. Older films continued to do well, their sales buoyed by the nickelodeons' need for product. With exchanges constantly complaining about the lack of new subjects, "it was necessary for a number of renters to purchase from manufacturers older subjects in order to supply the demands of the trade."[19] As a result, films made by Edison in 1904 sold more prints in 1906 than they had the previous year.[20] In April 1906 The Great Train Robbery was still considered the most popular film in distribution, showing the longevity of its appeal.[21]

Detailed records of the Kinetograph Department's finances survive for the 1906 business year, during which the cost of talent, properties, expenses, traveling, and so forth totaled $12,235, with negative costs averaging 81¢ per foot ($810 for a full 1,000-foot reel of film). The cost of producing a positive foot of film came to $.036, excluding negative costs, and $.0427 with the cost of negatives. The Edison Company produced 1,839,042 feet of finished film, which it sold at an average price of $.1027 per foot. Gross income from sales was $188,870. The potential profit margin, before deducting for general expenses such as advertising, salaries for the sales force, long-term investment, and general overhead, was exactly 6¢ per foot.[22]

The increase in Edison film sales for 1906 was remarkable, since the company continued to sell its product at a premium, giving an edge in pricing to competitors. As John Hardin, Edison's Chicago representative, told the home office: "Our 12¢ (per foot) price to the trade of course operates to a certain extent against our selling a large number of prints in competition to Pathe's and Vitagraph's prices, but at the same time if we have a sufficient supply to fill first orders when the new films first come out, we can dispose of a pretty fair number of prints, say from ten to twenty of a good subject at any time."[23] Although strong demand in the face of higher prices testifies to the continued popularity of Edison films, it also resulted from an industrywide product shortage.

Booming film sales kept Edison's factory for the manufacture of positive prints running at capacity. This allowed Porter to spend more time on individual films, to reduce his rate of production and thus to contradict the typical profit-maximizing response, which called for a rapid increase in production. Instead, Porter put greater emphasis on the elaborately wrought image, partially justifying the premium charge. Edison advertisements conveyed this attitude to potential purchasers:

Edison films are perfect in detail and action. No effort or expense is spared to produce THE BEST . The strictest attention is paid to details, situations, action and surroundings. We realize that Desperate Escaping Convicts and Pursuing Guards do NOT usually laugh; that Police Officers, after making an arrest, do not leave their clubs and helmets

Kathleen Mavourneen's house was burned in miniature.

behind them on the sidewalk, and that a Gale of Wind does not usually blow through private bedrooms.[24]

This ad from January 1906 compared Edison's carefully constructed, "realistic" films to several popular Vitagraph subjects. Vitagraph's "slapdash" methods often contributed vitality and spontaneity to the films, however, while also allowing for more rapid production.

Edison's new emphasis on the perfectly made, handcrafted image is apparent in Porter's The Night Before Christmas (December 1905), for which "the photographic and mechanical difficulties encountered and finally overcome if detailed would seem incredible." A panoramic view of Santa Claus driving "his reindeer over hills and mountains and over the moon" was done in the studio using miniatures of the sleigh and reindeer, an elaborately painted moving backdrop, and mechanical effects.[25] A copy of the film survives with different tints, allowing one to appreciate the complete visual impact. Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (February 1906), in which "some of the photographic 'stunts' have never been seen or attempted before,"[26] also reflected this new emphasis. Porter needed eight weeks to execute the array of special effects in this 470-foot, eight-minute film.

Porter's films grew more ambitious. Miniatures were also used for Dream of a Rarebit Fiend and for Kathleen Mavourneen (July 1906) when the heroine's house was burned for the camera. For Daniel Boone (December 1906) a log cabin set was built in Bronx Park, and Porter handpainted sections of the negative to create a fire effect. The "Teddy" Bears (February 1907), following the example of Vitagraph's A Midwinter Night's Dream , contains a sequence of object animation using stuffed bears: Porter worked eight-hour clays for a full week to shoot the necessary ninety feet of film.[27] Not all releases were produced with such attention to visual detail, but some—including Life of a Cowboy (May 1906), Kathleen Mavourneen , and Daniel Boone —presented complex narratives and large casts that required extensive preproduction.

Despite publicity, some Edison productions were made quickly and inexpensively, including Winter Straw Ride (March 1906), How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game (July 1906), and Honeymoon at Niagara Falls (August 1906). A few others—for example, The Terrible Kids (May 1906), Waiting at the Church (July 1906), and Getting Evidence (September 1906)—were made with care but without unusual effects, large casts, or far-off locations. Although the goal of the Kinetograph Department was to maximize sales on a per-film basis by offering a quality product, film sales indicate that the expense of "quality" could not be equated with popularity or high sales. The Night Before Christmas had sold 59 copies by March 1, 1907; Winter Straw Ride sold 57; Waiting at the Church , 52; and How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game , 59. Exchanges and exhibitors purchased 72 copies of Kathleen Mavourneen , 75 of Honeymoon at Niagara Falls , and 79 of Getting Evidence . Although the Edison Company sold 192 prints of Dream of a Rarebit Fiend and 109 of Life of a Cowboy , it also sold 146 copies of The Terrible Kids . A film's success had more to do with conception, timeliness, and ties to other kinds of popular and mass culture than to expenditures of time and money.

The Kinetograph Department altered some of its other practices in response to changing conditions in the industry. Porter's slow, if steady, move away from exhibitor-dominated cinema continued. The Kinetograph Department no longer sold individual scenes from acted subjects as it had done with How a French Nobleman Got a Wife . . . nor alternate combinations of scenes as with Life of an American Policeman .[28] Editing had become one of several procedures firmly integrated within the producers' repertoire. Efficiency was certainly one determinant in this development, since nonstandardization inhibited rapid print production at Edison's already overworked West Orange plant. The concept of film subjects as an interchangeable commodity also made such custom work inappropriate. Films were no longer sold to exhibitors—that is, to single users whose preferences might wisely and profitably be taken into account. Renters and exchanges now purchased the prints, rapidly circulating them to a variety of theaters. With purchasers no longer showing the films, the direct relationship between producer and exhibitor that had existed during the first ten years of the cinema was severed.

The Night Before Christmas also inaugurated a shift away from the socially relevant films that Porter had produced during 1904-5. The Edison films of 1906-7 were generally light entertainment, as the company favored subjects that had sold well during the previous year. Ten of the fourteen features made between December 1905 and June 1907 can be classified as comedies. Of the remainder, Life of a Cowboy, Kathleen Mavourneen , and Daniel Boone owed much to theatrical melodrama, while Lost in the Alps was a child-centered drama of a kind that had already proved its popularity. Regarding subject mat-

ter, Porter was probably working within limits imposed by his superiors, even though he retained considerable freedom within those limits.

Edison executives failed to capitalize fully on new opportunities within the industry. Rather than using all of its resources to respond to the nickelodeon's demand for product, the Edison Company continued to make films sponsored by outside firms. In January 1907 the popular singer Vesta Victoria was photographed in New York for the Novelty Song Film Company. That April Porter made a motion picture for the Colonial Virginia Company to be exhibited at the Jamestown Exposition. The film, which depicted the founding of Jamestown, required ten days of studio time, for which the client was billed $25 a day. For the entire production, the Kinetograph Department received $1,866.24.[29] In contrast, Life of a Cowboy generated over $11,000 in sales. Edison production efforts were further hampered in 1906 when Percival Waters' growing rental business expanded its Twenty-first Street offices at the expense of Porter's already cramped studio space.[30] Increasing the output of story films did not become a concern until the spring of 1907, in part because executives had not anticipated the high demand for prints and did not sufficiently enlarge their manufacturing capacities.[31] Nonetheless, R. K. Bonine, who was in charge of print production, worked as a traveling cameraman and was absent during much of 1906 and 1907. (His protracted absences, however, meant William Jamison usually assumed de facto responsibility.) In many areas of the Kinetograph Department, specialization was resisted and cost-efficiency studies were either not undertaken or ignored.

Edison's legal activities may have allayed any urgent desire to reorganize the company's production practices. After his motion picture patents case against the Biograph Company was dismissed in March 1902, Thomas Edison quickly applied for a patent reissue, which was granted on September 20, 1902.[32] One week later, Edison instituted new suits against Biograph, Selig, and Lubin.[33] Edison subsequently sued Georges Méliès, William Paley, Pathé Frères, and Eberhard Schneider on November 23, 1904.[34] Suit was also brought against Vitagraph in March 1905.[35] A year later Judge George W. Ray declared that the feeding device of the widely used 35mm Warwick camera was "different in principle and mode of operation from complainant's" and dismissed Edison's complaint against Biograph.[36] Edison lawyers appealed and won an important, if partial, victory in the court of appeals on March 5, 1907. Justices William J. Wallace, E. Henry Lacombe, and Alfred C. Coxe ruled that Edison's patents covered the standard camera used by most production companies but did not cover the special biograph camera used by the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company.[37] A complete victory either way would have sent the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, but this partial victory gave both sides what they needed most—a recognition of their patents. Biograph was finally freed from Edison's

legal harassments, and Edison had a ruling that strengthened his clout over other infringers. The New York Times assumed that this would enable Edison to soon eliminate most of his competitors (see document no. 18). The possibility that Edison might be able to dominate the industry through patents encouraged company executives to neglect other commercial opportunities.

DOCUMENT No. 18 |

MOVING PICTURE MEN HIT. COURT DECISION FAVORING EDISON COMPANY MAY CLOSE SOME PLACES. |

The moving picture business of the whole United States, which has grown to enormous proportions in the last few years, is affected by the decision of the United States Court of Appeals in deciding on March 6th that the moving picture apparatus of all the numerous companies in this country, with one exception, is an infringement on the patents covered by the Edison Co. . |

For over four years litigation has been in progress over the use of the special sprocket movement of the Edison apparatus, which is the vital part of the moving picture machine. This allows the film that is being drawn through a machine to stop for a small fraction of time, say a thirty-fifth of a second, and no other means has yet been discovered that will answer the purpose. |

It is said that many of the concerns making moving pictures will have to go out of business by reason of the decision. Owing to the demand, it is said that companies left in control of the field will be utterly unable to supply the wants of houses exhibiting moving pictures. Until they can catch up on their orders the exhibition houses will have to go out of business. |

SOURCE : New York Times , March 9, 1907, p. 2. |

Since the late 1890s Edison's legal activities had created a high level of uncertainty throughout the American industry and so discouraged investment. As this continued into the nickelodeon era, underfinanced American film manufacturers could not keep up with the demands for new product. Nonetheless, they responded more effectively than Edison. Once Vitagraph began to sell films in September 1905, production averaged about two headliners a month—more than twice the Edison rate. In March 1907 Vitagraph expanded to three and soon four important subjects a month. Sigmund Lubin increased production in mid 1906. By the summer of 1907 he, too, was approaching one new subject a

week. Selig was releasing about one feature a month by the second part of 1906. By mid 1907 the Chicago filmmaker had doubled that rate.[38] Although Biograph's legal position was the strongest, the firm faced financial difficulty. Filmmaking was seriously disrupted when Wallace McCutcheon departed for the Edison Company in spring 1905. After its new production head, Frank Marion, resumed regular production that July, Biograph averaged two features a month. Marion's departure for Kalem in January 1907, however, sent Biograph reeling. Although the firm still managed to turn out film subjects, few were popular, and Biograph was unable to pay interest on its loans.[39]

Since Edison's patent litigation threatened American producers more than their foreign competitors, it greatly facilitated foreign domination of the American screen. Films made by Pathé, Méliès, Gaumont, Urban-Eclipse, Nordisk, Italian "Cinès," and many other European companies poured into the United States, where they were purchased by product-hungry exchanges. In a statistical analysis of films released in the United States during the last ten months of 1907, Lawrence Karr found only 364 of 1,092 to be of American make.[40] While sales for some foreign imports were small, most films projected in American theaters were European. Moreover, Pathé firmly established itself as the dominant force in American cinema during 1906-7.[41]

Edison's desire to control the growing deluge of foreign, particularly Pathé, films, in conjunction with Pathé's anxiety over Edison's strong legal position, encouraged active negotiations between the two concerns early in 1907. As F. Croydon Marks, Edison's Paris-based negotiator, wrote to general manager Gilmore in April, Pathé Frères "are so busy at their works that they would be glad (if they could see themselves making the same money and with the same prospects of business) to be relieved of the control of the American territory."[42] Although the Pathé brothers did not make a formal offer, they expected to receive ten dollars per meter of negative and an additional royalty on prints. Finally they insisted that Edison "must undertake to buy one of all their films they now produce leaving it to us [Edison] whether we would make any positives or reproductions from them or not."[43] Since the cost of Pathé negatives was more than three times what Edison was then paying to produce its own films, Pathé's offer was not greeted with much enthusiasm.

Edison's March court victory may have convinced Gilmore that there were more effective ways for Edison to gain control over the American industry. His counter offer was simply to pay Pathé a per-foot royalty on prints sold.[44] Pathé felt that they had been led astray and that Edison had never intended to conduct serious negotiations. As Charles Pathé wrote in May,

Although we are glad of the opportunity we have had of making your personal acquaintance, you will allow us to express our regret at the want of commercial courtesy which the Edison Company has shown towards our company.

We cannot withhold from you that the refusal you have intimated to us might have been made a month and a half earlier, which would have prevented our Company from losing through it some hundred thousands of francs.[45]

Negotiations delayed Pathé's plans to open American printing facilities that would have reduced their costs approximately two cents for every foot of film sold.

When Gilmore tried to reopen negotiations, Pathé refused. Subsequently writing from Europe, Edison's general manager claimed to be relieved:

I find that the conditions are even worse than we ever suspected. They are putting out on the continent pictures that are not only nude but absolutely prohibitive from our standpoint. . . .

What we want to do is go ahead with our own lines. As Mr. Edison has well said, these outside entanglements do not prove to be of value, and I am firmly convinced that he is right in the conclusion. What Mr. Moore wants to do now is to push ahead the new studio, get out our own subjects and I am satisfied that we will be able to hold our own, not only in the American field but elsewhere.[46]

Whatever Gilmore may have truly felt about Pathé, the Edison Manufacturing Company found itself on the commercial defensive by spring 1907. Other companies had taken better advantage of the rapidly changing conditions within the motion picture industry.

Production Practices at Edison

Edison production practices remained the virtual antithesis of the studio system that would develop in response to the nickelodeon boom. The informal, sometimes haphazard collaboration that had characterized the making of The Buster Brown Series (1904) continued as Porter and McCutcheon produced Daniel Boone; or, Pioneer Days in America in December 1906. Florence Lawrence, who played Boone's daughter in her first screen appearance, subsequently detailed the production process and underscored these continuities (see document no. 19). Rather than having a continuous production schedule, the Edison staff geared up for each new undertaking. The Kinetograph Department lacked a stock company and hired actors on a per-film basis. Porter frequently relied on traveling theatrical troupes to supply performers who had worked together and could contribute costumes and props. In the case of Daniel Boone , actors were not from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, as Lawrence recalled (it was then in Europe), but from the spectacle Pioneer Days , which opened at the Hippodrome on November 28, 1906, and ran through December and into January.[47] This meant that they had other commitments: on matinee days, filming was precluded. Other actors, such as Lawrence, were hired through casting calls. Production personnel also continued to be used in bit parts, for which they

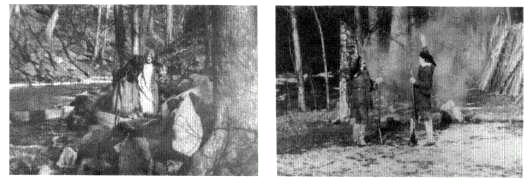

Daniel Boone. Boone's daughter (Florence Lawrence) befriends an Indian maid in the first scene. Later,

Daniel Boone and his companion swear vengeance in front of the hero's burned house.

received double pay as a bonus. Appearing in a picture was a way for everyone to pick up some extra cash: it was not a primary commitment. Production schedules were dictated by the availability of performers rather than the reverse.

DOCUMENT NO. 19 |

My mother heard that Edwin S. Porter, then the chief producer and manager at the Edison studio on Twenty-first street, was engaging people to appear in an historical play. I decided to see him at once. My mother accompanied me to the studio. |

The news of intended activity on the part of the Edison people must have been pretty generally known, for there were some twenty or thirty actors and actresses ahead of us that cold morning. I think it was on December 27th, 1906. At least it was during the holidays. Everybody was trying to talk to Mr. Porter at one time, and a Mr. Wallace McCutcheon, who was directing Edison pictures under Mr. Porter, was fingering three or four sheets of paper, which I found later were the scenario. |

Mr. Porter and Mr. McCutcheon conferred together and Mr. Porter announced that only twelve people were needed for the entire cast, and that some of these had been engaged. He next read off some notes he had made during his conference with Mr. McCutcheon, about as follows: |

One character man who can make up to look like Daniel Boone. |

One character man to play Daniel Boone's companion. |

One middle aged woman to play Mrs. Daniel Boone. |

Two young girls about sixteen years old to play Daniel Boone's daughters. |

(Text box continued on next page)

One young girl who can make up like an Indian maid. |

Six men who can make up as Indians. |

The part of Daniel Boone, his companion, the Indian maid and a couple of the bloodthirsty savages, he announced, had been filled. That left the parts of Mrs. Boone, the two Boone girls, and four Indians open. As I remember, Col. Cody's Buffalo Bill show was then in New York City and the people selected to play the parts he announced as "filled" were from the show. |

Mr. McCutcheon looked at me, then at Mr. Porter and I was told that I was engaged as one of Daniel Boone's daughters. I must have said something to mother almost instantaneously, for one of the men, I forget which, asked, "Is this your mother?" I replied that she was, and Mr. Porter thereupon engaged her to play the part of Mrs. Daniel Boone. |

Our names and addresses were taken and we were told "that was all" for the time being, and that we would be notified when to report at the studio. We were to receive five dollars a day for every day that we worked. |

There was none in the cast who knew the title of the play until we reported for work on January 3, 1907. At this stage of the motion picture industry the producers were very secretive about such matters. "Daniel Boone; or Pioneer Days in America," was announced as the name of the play. We began work on the exterior scenes first. |

Besides mother and myself, others who were playing the principal roles were Susanna Willis, and Mr. and Mrs. William Craver. Mr. Porter and Mr. McCutcheon were the directors. It was during the production of this picture that I learned that the photoplay "Moonshiners," which I had witnessed some three or four years previously, was the first dramatic moving picture ever made in America, and that Mr. McCutcheon was the man who directed it. |

All of the exterior scenes for the Daniel Boone picture were photographed in Bronx Park. As one of Boone's daughters I was required to escape from the Indian camp and dash madly into the forest, ride through streams and shrubbery, until I came upon Daniel Boone's companion. As a child I was fond of horses and had always prided myself on being able to handle them, but the horse hired by Mr. Porter was evidently of a wilder breed than the ones I knew. I couldn't do anything with him and he ran off no less than five times during the two weeks we were making the exterior scenes. I was not thrown once, however. |

During all this time the thermometer stood at zero. We kept a bonfire going most of the time, and after rehearsing a scene, would have to warm ourselves before the scene could be done again for the camera. Sometimes we would have to wait for two or three hours for the sun to come out or |

(Text box continued on next page)

get it just right for the taking of a scene which required certain effects. The camera was also a bother being a great clumsy affair. |

One afternoon we didn't pay sufficient attention to the bonfire and permitted it to spread. The fire department had to be called out to prevent its burning and ruining all the trees in the park. While beating the blaze away from a tree Mr. Porter discovered a man who had committed suicide by hanging himself, probably while we were working on the picture. We did not do any further work that day. |

All the interior scenes were made at the Edison studio, on the roof, where the stage space would accommodate but one set. We could only work while there was sunlight as arc lamps had not then been thought of as an aid to motion picture photography. Three weeks were required to complete the picture. |

SOURCE : Photoplay , November 1914, pp. 40-41. Tom Gunning generously brought this article to my attention. Florence Lawrence's dates are incorrect: the completed film was copyrighted on January 3, 1907. William Craver had supplied the horses for Porter in the somewhat earlier Life of a Cowboy (May 1906), and he probably did so for this film too, as well as appearing in it (Moving Picture World , December 7, 1912, p. 961). |

A lack of efficiency was evident in several areas. The decision to film Daniel Boone , ill suited for winter production, suggests an absence of careful planning. But whatever Porter chose to make, productivity slowed each winter when the days grew short. Stormy weather would also have precluded shooting. Unlike the Biograph studio, Edison's Twenty-first Street facilities lacked electric lights, not because Porter was indifferent to the technology, but because the small, glass-enclosed studio could not accommodate them. Despite such obstacles, the three-week shooting schedule for Daniel Boone was still extremely protracted. (Two years later, Griffith would handle the same type of story in a few days.) Characteristically, Porter focused on visual details rather than the major thrust of the narrative. With only a few daylight hours available for filming, time spent on achieving photographic effects was costly and not always successful. Rather than reconceive the more time-consuming setups, Porter adapted the production schedule to his filmmaking goals.

Porter and McCutcheon relied on collaborative, nonspecialized working methods. Although Porter was studio manager, he worked with the sets and operated the camera, while McCutcheon was in charge of the actors. America's top two filmmakers from the pre-nickelodeon era thus worked in tandem rather than establishing separate production units or a clear hierarchy. Decisions were made laterally rather than vertically. Both men, in fact, were accustomed to operating in this manner. Porter had collaborated with George S. Fleming, James White, and G. M. Anderson, while McCutcheon had worked closely with Frank Marion.

The Daniel Boone scenario was a joint responsibility and reflected the Porter-

McCutcheon partnership. Like many films, it emerged from a melange of precursors. Only part of the film's title and not the plot was taken from the Shubert spectacle. The picture was an adaptation of Daniel Boone: On the Trail , one of several Daniel Boone plays written and produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[48] At the same time, Daniel Boone; or, Pioneer Days in America owes much to two McCutcheon/Biograph films: The Pioneers and Kit Carson . The focus on family, not as central to McCutcheon's earlier dramas, places Daniel Boone squarely within Porter's family-centered orientation.

Porter's old middle-class predilections remained as apparent in his production methods as in the themes and subject matter of his earlier films. Although the New York studio was called a factory, the manufacturing division of labor was not in evidence. Porter insisted on acting as producer, scenarist, cameraman, and editor. Beyond this he was also involved in refining the projecting kinetoscope and the construction of Edison's new Bronx studio. (Bronx Park was chosen as a location for Daniel Boone because it was nearby.) As George Blaisdell defined Porter's role, "During this period he made all the pictures, built and designed the cameras, wrote many of the scenarios, staged all the productions and operated the camera. He did in fact produce the pictures."[49]

The Issue of Narrative Clarity—Audience Familiarity

The Edison Manufacturing Company's continued reliance on pre-nickelodeon production practices was not confined to filmmaking as such, but included the ways that viewers were expected to understand the resulting subjects. Methods of reception or appreciation remained much as they had been since the late 1890s. Representational practices fell into three basic categories, with the basis for comprehension centered either in the spectator, the exhibitor, or the film itself. None of these dominated or was necessarily preferred. In fact, they were complementary and often interdependent. All involved redundancy in different forms.

Porter and his contemporaries continued to rely on audience awareness of hits, crazes, and well-known stories within popular culture. This meant a different relationship between audience and cultural object than in more elevated culture, where narratives were usually presented with the assumption that audiences were encountering them for the first time. The Night Before Christmas (December 1905) "closely follows the time honored Christmas legend by Clement Clarke Moore, and is sure to appeal to everyone-both old and young."[50] Lines from the poem were used to introduce several scenes, helping the audience to maintain a conscious correspondence between the screen drama and the book, continuing a representational practice evident in Uncle Tom's Cabin . Relying on the audience's previous knowledge of Moore's poem, Porter established the necessary narrative clarity even while instilling a degree of nostalgia for lost childhoods. The film's success depended primarily on the spectacle and

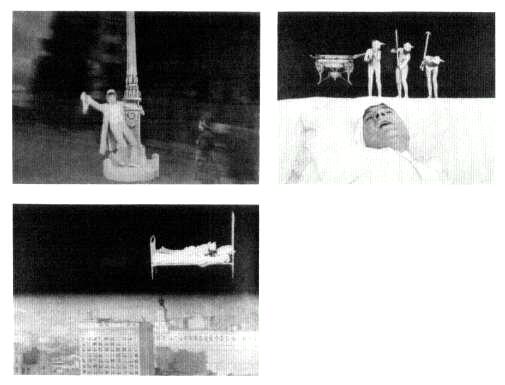

Dream of a Rarebit Fiend, scenes 2, 4, and 6.

novelty of Porter's execution—on the way he told a familiar story, not on the novelty of the story itself.

The next Edison film, Dream of a Rarebit Fiend , was partially inspired by Winsor McCay's comic strip "Dream of the Rarebit Fiend," which had appeared in the New York Telegram since 1904.[51] Porter not only borrowed the title but shared McCay's dream-based narrative structure, elements that had already figured in Biograph's somewhat earlier Dream of the Race-Track Fiend (September 1905). Likewise, the Edison film convincingly realized McCay's surreal imagery on the screen using a variety of photographic tricks—an achievement not attempted in the earlier Biograph film. Although such visuals had many antecedents, Porter may have found another McCay strip, "Little Nemo in Slumberland," a useful point of departure. The basic story line and some of the film's visuals, however, can be found in an earlier Pathé film made by Gaston Velle—Rêve à la lune (1905):

A brave drunkard is surrounded by gigantic bottles in human form, with which he executes a wild, disorderly quadrille. Next he sleeps. . . . He fancies himself in a public square under the kindly gaze of the moon, with which he immediately falls in love.

He wishes to reach it and, to do this, grabs onto a lamp post. But the moon is still too far away. Our man does not hesitate but jumps the wall of a nearby house. . . . Not without several pitfalls, he reaches the roof of the house, on which he has difficulty maintaining his balance, for there are several close calls when he could have been hurled down into the void. He falls while crossing an attic window and disturbs the neighbors.

But our obstinate drunkard still wants to catch the moon. He leans against a chimney-flue, which wobbles on its base. Suddenly a hurricane appears and carries our man into space, always riding the flue. He covers many miles, crossing the clouds while the storm rages around him. He is in outer space, about to catch the object of his desire. The moon itself awaits his efforts, approaches him and extends its hospitality to him. He resolutely enters the brilliant star and penetrates its mouth. But the moon does not seem to take warmly to the visitor, for after several expressions of distaste, it spits the poor drunkard into space, and we see him rapidly tumble toward earth to end up finally in his bed, where he immediately awakens from his strange dream.[52]

Porter's use of the McCay title not only provided a frame of reference that helped audiences understand the dream transitions but obscured his borrowings from the Velle narrative. Familiarity with the McCay comic strip was not as necessary to audience understanding of the narrative as it was for many other films. In this respect, Dream of a Rarebit Fiend conforms to more modern expectations of adaptation.[53]

The film begins with a medium shot of the fiend consuming large amounts of alcohol and Welsh rarebit. For subsequent scenes, Porter employed a different special effect for each shot, keeping the spectator off balance and making it impossible for the average viewer to figure out how the photographic stunts were achieved. The second shot was a double-exposure, superimposing the fiend and a swinging white lamppost against rapidly panning, zigzagging camerawork of New York City streets. It suggested the subjective sensation of the fiend's predicament without being a point-of-view shot. When the man enters his bedroom (scene 3) invisible strings drag his shoes across the floor and stop action causes the furniture to disappear. The fourth scene uses a split-screen effect—juxtaposing a close-up of the sleeping fiend with a far shot of people in devils' costumes, making it appear that they are hitting him on the head with forks and shovels. When Porter cuts back to the room, it is a miniature that allows the filmmaker to manipulate the bed in astonishing ways. The sixth scene uses another type of split screen as the fiend's bed travels across the skyline of New York. Scene 7 uses a drawn background and cut-outs. Scene 8 is a studio close-up of a steeple on which the fiend is skewered. The final scene returns to the bedroom as the dreamer crashes through the roof and wakes up. The changing tricks and discontinuities disorient the spectators in ways analogous to dream, particularly the dreams portrayed in Winsor McCay's comic strips.

The Terrible Kids (April 1906) was part of the widespread comic depiction of undersocialized youth. In the cinema, the popular bad boy genre would soon

This Winsor McCay cartoon strip shares many similarities with Dream of a Rarebit Fiend.

Little Nemo's dream, however, is caused by too many donuts.

The "terrible kids" and their faithful dog wreak havoc on the adult world.

come under heavy criticism for providing young viewers with undesirable role models. Porter's comedy shows two boys disrupting a neighborhood's routine with the help of their dog, played by Mannie. Every scene is a variation on a mischievous prank: Mannie "jumps onto the Chinaman's back, seizes his queue and drags the poor chink to the ground"; when they encounter a billposter on a ladder, the dog "grabs the billposter by the leg of his trousers and he falls to the ground with the ladder on top of him while the kids enjoy the billposter's predicament."[54] Several women and an Italian apple vendor with a push cart are also victims. Eventually these annoyed adults turn pursuers and capture the two pranksters with the help of the police. As the boys are driven off in the police van, Mannie opens the van door, and the kids escape as the film ends.

Delinquent kids appear constantly in early film comedies. James Williamson's The Dear Boys Home for the Holidays (1903) and Our New Errand Boy (1905), Biograph's The Truants (1907) and Terrible Ted (1907); Pathé's Les Petits Vagabonds (1905), and Porter's own The Little Train Robbery (1905) are just a few additional examples of the bad boy genre. Others such as Biograph's Foxy Grandpa Series (1902) and Edison's Buster Brown Series (1904) had comic strip antecedents and also became plays. The Amusement Supply Company offered a full program of five films and fifty-two "life model" stereopticon slides on Peck's Bad Boy and His Pa , which were meant to illustrate the best-selling book of the same title.[55] In all of these films one or two boys disrupt staid adult life and undermine authority. While Foxy Grandpa outwits the boys on their own terms (showing that the child exists in all of us and that Grandpa is entering a second childhood), more often than not the adults are easily fooled.

The relationship of The Terrible Kids to similar films (and to the bad boy genre in other popular forms) was an essential part of the film's meaning. Since the boys in these films were anonymous, intertextual and intratextual redun-

dancy were essentially of the same kind. The audience's frequent encounters with similar texts provided the reassurance of familiarity. Audiences were expected to identify and sympathize with the kids, suggesting a nostalgic desire for a simpler, less regimented past. According to the catalog description of The Terrible Kids , "The antics of the kids, the almost human intelligence of 'Mannie' and the narrow escapes from capture, are a source of constant amusement and are sure to arouse a strong sympathy for the kids and their dog."[56] The genre savors the rejection of authority even as it offers a momentary release from the increasingly regimented workplace. The bad boys escape at the end of both The Terrible Kids and The Little Train Robbery —as if to appear in some other film.

While scanning the newspapers of this period, one constantly stumbles across antecedents for American films. This suggests that virtually every film functioned within a well-established intertextual context. Even a film with as simple and obvious a narrative as How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game conformed to a popular stereotype. Released in July 1906, much of the subject was recycled from Play Ball , a topical film Porter had shot the previous year on opening day of the National League baseball season. A week after that game, the New York World published a full-page photograph of the crowd with the caption, "If your office boy or any of your clerks had sudden calls to the funerals of grandmothers or uncles on that memorable Saturday perhaps you might shed a little light on the matter by a close scrutiny of this picture."[57] This caption articulated the premise of Porter's film. In a small office, the lady stenographer writes a note for the office boy that reads "Dear Teddy: Come home at once. Grandma is dead." The boss accepts the excuse and the office boy has a free afternoon to see the game. The young lady stenographer faints in disbelief when the boss falls for the explanation. The bookkeeper is told to escort her home. Left alone, the broker also decides to take the afternoon off and see the game. The remainder of the film intercuts Teddy on a telephone pole looking through a spyglass with masked point-of-view shots of the game—including a view of the boss discovering the stenographer and bookkeeper in the stands (the matte, as was customary, was added at the printing stage). For a short time they are all kids again, playing hooky from adult responsibility. Unlike Teddy, whose skylarking remains undetected and hence unpunished, the stenographer and bookkeeper are reprimanded by authority. They play by some rules (they pay to see the game) but not others. Teddy, safe on his distant perch, does not pay to see the game (either with money or by suffering the boss's wrath). Like the "terrible kids," he can disregard societal rules and get away with it—something adult characters seldom succeed in doing.

In How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game , Porter celebrates baseball as a unifying activity that cuts across age and class barriers. Movie patrons are encouraged to recall their childhoods nostalgically, for they see the game through

The office boy sees not only the ballgame but his boss lecturing the bookkeeper and stenographer for attending the game.

the office boy's spyglass—from his point of view. The spectator, however, regresses nostalgically to his childhood. Gender is presumed to be male—like the filmmaker and the office boy. As Adrienne Harris has pointed out, "Baseball is centrally a place without time and without women."[58] In 1906 the game reflected the male-dominated world in which and about which Porter and others made their films. Whether the stenographer is in the office or at the ballgame, her position is in the margins. She never speaks in her own voice. She writes Teddy's note—signing someone else's name, and her main job is to record the male boss's words. Even when she faints, it only becomes an excuse for the bookkeeper to escape as well. Likewise in baseball, if a woman speaks, Harris suggests, it will be as "a false mock male self."[59] In How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game , the boy's point-of-view shots of the game reproduce the male-fetishized close-up of the woman's ankle in The Gay Shoe Clerk , but in an appropriate latency-age form. Women spectators of both The Terrible Kids and How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game are likewise forced to assume the role of a false mock male self to enjoy the films in the spirit in which they were made.

Obadiah Binks tries to elude his family, and his jilted bride is left "waiting at the church."

While The Terrible Kids conformed to a genre diffused throughout Western popular and mass culture and How the Office Boy Saw the Ball Game was based on a generalized, urban American witticism about office boys and ballgames, Waiting at the Church (July 1906) required spectators to be familiar with the lyrics of one specific song, a hit popularized by Vesta Victoria (see document no. 20). As one vaudeville manager noted, "to those who know the song, this is extremely funny."[60] The film itself was described in Views and Film Index :

WAITING AT THE CHURCH

Obadiah Binks is sitting on a bench in the park. A young lady strolls along and finally seats herself very comfortably on the same bench. Before long they engage in conversation and Obadiah proposes. At first she is surprised by the very sudden announcement of his love for her, but she suddenly falls upon his neck and hugs and kisses are mutual. He declares his love for her and they agree upon a date to get married.

Obadiah's home is then shown. Finally the young lady is seen waiting at the church for Obadiah. He does not come but sends a messenger with a note in which he states, "Can't get away to marry you today: my wife won't let me."[61]

This brief trade description passes over Porter's elaboration of the song's simple story. Porter did more than merely illustrate the song. Although the original lyrics are from the woman's point of view, the film shifts the focus to Obadiah Binks. No longer a con artist who robs a naive, sexually frustrated woman of her money, Obadiah is portrayed as a zany bigamist trying to outwit one wife so that he can marry a second. The discrepancy between the lyrics and the film narrative is an essential part of the picture's humor. The film's farcical tone is retained, but the story is explored from a new perspective.

DOCUMENT No. 20 |

WAITING AT THE; CHURCH |

Written by Fred W. Leigh Composed by Henry E. Pether Published by Francis, Day and Hunter [New York, 1906] |

1. I'm in a nice bit of trouble |

Somebody with me has had a game |

I should by now be a proud and happy bride |

But I've still got to keep my single name |

I was proposed to by Obadiah Binks |

In a very gentlemanly way |

Lent him all my money so that he could buy the home |

And punctually at twelve o'clock today |

Chorus: |

There was I waiting at the church |

Waiting at the church, |

When I found he'd left me in the lurch |

Lot, how it did upset me! |

All at once he sent me round a note |

Here's the very note |

This is what he wrote |

Can't get away to marry you today |

My wife won't let me. |

2. Lor, what a fuss Obadiah made of me |

When he used to take me to the Park |

He use to squeeze me till I was black and blue. |

When he kissed me he used to leave a mark. |

Each time he met me he treated me to wine |

Took me now and then to see the play |

Understand me rightly when I say he treated me |

It wasn't him but me that use to pay. |

Just think of how disappointed I must feel |

I'll be going crazy very soon |

I've lost my husband the one I never had |

And I dreamed so about my honeymoon! |

(Text box continued on next page)

I'm looking for another Obadiah |

I've already bought the wedding ring |

There's all my little faltheriddles packed in my box |

Yes, absolutely two of everything. |

With Waiting at the Church , Porter used redundancy in several different ways. The song's familiarity was incorporated into the psychology of the characters as well as the narrative. When Obadiah is chased by his wife and children, they seem to have gone through this routine before. Determined to keep the family together and knowing what to expect, they prevent him from reaching his would-be bride "waiting at the church." Actions and situations are also repeated through the use of similar chase scenes. Like the chorus of the song itself, redundancy is the central organizing principle of the film.

The "Teddy" Bears was not only one of Porter's personal favorites but serves as a rich, revealing example of the filmmaker's work in the early nickelodeon era.[62] Advertised as "a laughable satire on the popular craze,"[63] Porter and McCutcheon's first film of 1907 was completed in late February. The juxtaposition of two different referents is an important element of The "Teddy" Bears ' humor and success. It starts out as an adaptation of "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" and works within the framework of the fairy-tale film. For the first two-thirds of its running time, the life-sized teddy bears (actors in costume) are the subject of an endearing children's film. Suddenly the picture moves outside the confines of the studio, changing moods and referents. The bears chase Goldilocks across a snowy landscape until "Teddy" Roosevelt intervenes, kills the two full-grown pursuers, and captures the baby bear.

The sudden appearance of "Teddy" was based on a well-known incident when President Roosevelt was on a hunting expedition in Mississippi and refused to shoot a bear cub. This was in November 1902. Shortly thereafter Morris Michtom, a Russian immigrant who ran a small toy store and would eventually start the Ideal Toy Corporation, began to make and sell "Teddy's bear"—a stuffed version of the spared cub. The novelty had become a craze by 1906-7, when thousands of toy bears were being sold each week and music such as "The Teddy Bear March" (copyrighted 1907) was popular.[64] Unless audiences appreciated the shift in referents, the killing of the two endearing bears seemed bizarre and at odds with the earlier part of the film. Sime Silverman missed the point in his Variety review when he wrote:

Probably based on the fairy tale of "Goldielocks and the Three Bears," The Teddy Bears series at the Colonial this week is made enjoyable through the mechanical acrobatic antics of a group of fluffy haired little hand-made animals. The closing pictures

The "Teddy" Bears unexpectedly shifts moods from animated stuffed animals in the first part to the

killing of anthropomorphic bears in the second. Porter also juxtaposed location shots with exterior

scenes set in the studio.

showing the pursuit of the child by the bear family is spoiled through a hunter appearing on the scene and shooting two. Children will rebel against this position. Considerable comedy is had through a chase in the snow, but the live bears seemed so domesticated that the deliberate murder in an obviously "faked" series left a wrong taste of the picture as a whole.[65]

Not everyone agreed with Sime.[66] The shift in referents revealed to the audience that The "Teddy" Bears was not simply a children's film, but was also aimed, like Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland , at adults. By judging the film from the viewpoint of a child, who could not be expected to grasp a range of contemporary references, Sime postulated a relation between viewer and cultural object that would be more applicable to later cinema. In fact, his review is one of several indications that criteria for assessing films were changing and that subjects relying on an audience's prior familiarity with narrative elements were being received with less sympathy.

The "Teddy" Bears is a political burlesque on Teddy Roosevelt, reminiscent of Terrible Teddy, the Grizzly King and The Strenuous Life; or, Anti-Race Suicide . As Sime noted, the bear family's anthropomorphic activities have endeared the animals to the audience by the time the Roosevelt hunter appears on

the scene. Audiences then tend to react unsympathetically to his shooting of the two adult bears. The liberal press sometimes expressed a similar viewpoint. After Roosevelt killed a she bear in 1907, the New York World responded with a front-page column devoted to the critical remarks of nature writer Dr. William J. Long. Headlines read: "Calls Roosevelt Bear Killing Pure Brute Cowardice."[67]

Porter's continuing commitment to pre-nickelodeon representational strategies is also evidenced in the shot construction of The "Teddy" Bears . The film has eighteen shots: the first thirteen and the last were taken in the studio, while the four chase scenes were photographed outside in a city park. Although Griffith was to shoot interiors in the studio and exteriors on location on a regular basis by 1909, Porter never developed this convention of consistent mimetic realism, at least in his Edison films. From our post-Griffith perspective, studio scenes of the bear-house exterior are at odds with those photographed in the park. Although this syncretism can feel misplaced or naive today, Porter's studio work was generally motivated by a desire for greater control over the mise-en-scène. Correspondingly, Porter's frequent reliance on the chase encouraged location shooting and prevented films from becoming claustrophobic.

Shots continued to be conceived as discrete units in The "Teddy" Bears , even though editorial control was firmly in Porter's hands. As before, each scene has its own self-enclosed temporality, which is related to outgoing and incoming shots by repeated actions and the unfolding story. Goldilocks' exit through a hallway (shot 7) is followed by an entrance into the bedroom (shot 8), another example of Porter's familiar uses of the temporal overlap. There is no matching action or linear continuity. Mismatches in screen direction and conflicting entrances and exits further reveal the discrete nature of individual scenes. The "Teddy" Bears makes rich and effective use of a representational system Porter had explored and developed since his arrival at Edison. Within this system, he continued to mature as a filmmaker.

Porter drew on the same repertoire of techniques in Cohen's Fire Sale (June 1907), which focuses on a Jewish milliner whose merchandise is inadvertently taken away by a garbage man and ends up in the city dump. The shopkeeper recoups his investment by starting a small fire in his store and covering the damage through insurance. He benefits still further by a fire sale, which quickly clears the store of imperfect goods. The story is based on the stereotypical Jewish businessman for whom fire was "our friend" and the fire company was "our enemy"—a view rendered in iconographic form on a comic postcard of the period. The story itself is quite simple and clearly depicted; but character motivation, narrative logic, and audience comprehension of a few key pieces of information—for instance that a piece of paper is an insurance policy—relies on this highly specific anti-Semitic stereotyping. Here redundancy reinforces those ethnic prejudices that audiences initially relied on to understand the film.

An anti-Semitic "comic" postcard of the period.

Cohen's Fire Sale integrates pasteboard representations and actual objects in extreme ways. Hats in the foreground of Cohen's display are real—those in the background are painted. Cohen's sleeping cat suddenly becomes a pasteboard animal when its tail is tied to the kerosene lamp. Though these syncretic juxtapositions differ little from Porter's set-design strategies in The Finish of Bridget McKeen (1901), the quality and detail of execution have improved. Again the exterior of Cohen's store is a set, while other scenes were filmed on New York City streets. Scenes of a fire truck coming out of the station and of the firefighting are actuality material, taken of a fire company in action. Like Porter's previous work, Cohen's Fire Sale incorporates a diversity of mimetic representations and undercuts any notion of a seamless continuity. Shots continue to act as self-contained units of representation in other ways as well. Chase scenes integrate narrative elements like the pursuing shopkeeper with superfluous incidents that had appeared in turn-of-the-century, one-shot films. In one scene, for instance, street gamins wear some of Cohen's misplaced hats and dance a cakewalk until Cohen arrives to take away the headwear.

Porter's construction of shots and his frequent reliance on audience familiarity with a film's subject were part of the same representational system. If one shot did not follow clearly after another or if extraneous elements were introduced, audiences had a frame of reference that allowed them to fill in gaps or follow the narrative's main line. If spectators lacked the necessary frame of reference, they missed the joke or could not follow the story line. Novelty of

Cohen tries to sell his damaged goods.

execution and familiarity of subject matter were the basis of this approach. Although Porter's reliance on the audience's prior knowledge was extreme for the period, it nonetheless characterized and crystalized the distinctive elements of this period's representational system.

Self-Sufficient Narratives and Intratextual Redundancy

Narrative clarity was often achieved through intratextual redundancy. Two common structuring principles proved especially efficacious in this respect: first, discrete scenes could be gathered around a unifying theme or character; second, as a corollary, scenes could be built around a chase. Redundancy of situation, which Porter had used in The Buster Brown Series and The Seven Ages , was also utilized for comedies like The Nine Lives of a Cat (July 1907) and The Rivals (August 1907). After evoking the age-old adage about cats with its title, The Nine Lives of a Cat proceeds to show nine unsuccessful attempts to eliminate an uncooperative feline. The Rivals , based on a comic strip by T. E. Powers that ran in the New York American ,[68] showed two male rivals fighting over the attentions of a desirable woman. In one scene Charlie escorts Tootsie, only to have her stolen away by George. In the next scene George escorts the girl, only

The Rivals (left): a romantic triangle that soon self-destructs. It was based on a cartoon series (above).

to have her stolen away by Charlie. This continued until Porter had the desired number of scenes. To achieve closure, he had the woman leave both rivals for a third. The organizing principle of such films was indebted to the repetitive structures of daily and weekly comic strips. (The strip alternated combinations each week.) Repetition with slight variation is the basis for their comedy. Similar structures occur in somewhat later Porter/Edison films like Laughing Gas (November 1907) and The Merry Widow Waltz Craze (April 1908).

While the chase also utilizes a repetitive structure, it achieved added levels of

clarity by setting up a simple opposition between pursuer and pursued that could be expressed compositionally by foregrounding first one group and then the next, and through movement, as the pursued and pursuers come toward and past the camera. Although Porter made a few simple chase films such as From Rector's to Claremont , he soon combined the chase with other forms of in-tratextual redundancy, as in "Raffies "—the Dog (June 1905), The Terrible Kids , and Getting Evidence .

In Getting Evidence (September 1906), a jealous husband visits the Hawk-shaw Detective Agency (a redundant naming device in its own right) and asks the detective to obtain evidence of his wife's supposed infidelities. Only a photograph is deemed acceptable evidence and the private eye's attempts to secure it provide a series of comic incidents. The detective becomes a surrogate authority figure with the right to pry. Soon he is pursuing a woman he believes to be the man's wife. Each time he takes a picture of the woman and her lover, his camera is destroyed and he is roughed up. He is run over by a car; when posing as the couple's waiter, he is doused with seltzer. When the determined photographer sneaks up on the romantic couple at night and uses a flash, his subjects destroy the camera once again. At the seashore he takes a successful picture, hides the negative and then "is pursued by a crowd, caught and ducked thoroughly in the surf."[69] When the black-eyed, limping detective finally presents his evidence to the husband, his photograph is of the daughter rather than the wife.

Rather than providing evidence against the wife, the photograph exposes the detective's incompetence and the husband's unfounded suspicions. As Alan Trachtenberg points out, the authority of the patriarch and his surrogate eye is mocked and loses some of its authority.[70] As Biograph's films of the Westinghouse works in East Pittsburgh (taken in 1904) clearly show, surveillance was commonly directed against the working class in factories. Such people, who provided the nickelodeons with a majority of their patrons, undoubtedly were amused to find someone like their boss and his delegated representative in such a predicament. As with The Terrible Kids , this suggests that films could be appropriated by working-class audiences in ways never anticipated by Porter and yet consistent with his own opposition to a regimented workplace. The humor touches on an important issue of American life without dealing with it directly as Porter did in The Kleptomaniac and The Ex-Convict .

Porter's use of intratextual redundancy was simple and effective; it allowed for the production of one-reel films without complex narratives. Similar films were made by other producers in considerable quantity. Many of these can still be seen, including Biograph's Mr. Butt-In (February 1906) and If You Had a Wife Like This (February 1907), Vitagraph's The Jailbird and How He Flew (July 1906) and Liquid Electricity (September 1907), Hepworth's The Fatal Sneeze (June 1907), Urban's Diabolo Nightmare (October 1907), Eclipse's A Short-Sighted Cyclist (1907), and Gaumont's Une Femme vraiment bien (1908).

Getting Evidence. The disguised detective takes a snapshot.

The titles of all films played an important naming function, either defining the central concept or suggesting the referent viewers needed to interpret the film even before the narrative began. Redundancy, one of the defining characteristics of "low" popular culture as opposed to "high" art[71] was essential to the narrative cinema of 1906-7, as it had been to the films Porter produced in earlier years.

Severe limitations were placed on other kinds of self-sufficient narratives in pre-1908 films. If a story was unfamiliar, how was the spectator to know if a succeeding shot was backwards or forwards in time? The temporal, spatial, and narrative relations between different characters and lines of action were often vague or, worse, confusing. Visual cues like repeated action were helpful, but not always possible. Occasionally the producer used intertitles, but this practice was not universally accepted and was rarely used at the Edison studio during 1906-7. One limited solution was to tell simple stories. This is what Porter did with Lost in the Alps (March 1907), a family-centered drama of twenty-four shots (see shot-by-shot breakdown on page 358).

The family unit established in the opening two shots is quickly threatened as the children wander through a snowstorm and succumb to the elements (shots 3-5). The worried parents are the focus of the next four shots and their rescue

(text continued on p. 359 )

Lost in the Alps, Shots 1, 2, 7, 19.

Shot 23.

Lost in the Alps: a shot-by-shot breakdown. | |

shot 1. | exterior of house (set)—mother sends son and daughter off right with lunch basket. |

shot 2. | sheep's meadow—children come from deep left and give lunch to father, a shepherd. |

shot 3. | children staggering home through woods—snow falling. |

shot 4. | children struggling through snow—girl struggles off right carrying younger brother as snow falls. |

shot 5. | children collapse. |

shot 6. | mother working at home (interior, set)—she looks at clock, is very worried and goes outside. |

shot 7. | exterior (same as shot 1)—mother comes outside, she goes off right and returns discouraged, then reenters house. After a brief moment, the father comes on right and enters the house. |

shot 8. | interior of house (same as shot 6)—mother is waiting and husband enters; he hears the news and quickly leaves. |

shot 9. | interior of monastery—father enters from right and explains the situation to monks, who go off and reenter with two Saint Bernard dogs. |

shot 10. | dogs race through the snow. |

shot 11. | dogs race through the snow. |

shot 12. | dogs race through the snow. |

shot 13. | dogs race through the snow. |

shot 14. | dogs race through the snow. |

shot 15. | dogs race through snowy countryside. |

shot 16. | pan from stream to dogs going down path. |

shot 17. | dogs race through snow, downhill, and across stream. |

shot 18. | dogs race across snowy fields. |

shot 19. | dogs race down steep slope. |

shot 20. | dogs sniff where children were last shown collapsing (shot 5), but the children cannot be seen. |

shot 21. | father and monks come down snowbank and are greeted by one Saint Bernard. |

shot 22. | same location as shot 20, but children are now in the snow; monk and father enter frame, embrace children, and wrap them in blankets. |

shot 23. | home, same set as shot 6—mother at home, father and men return with children, who are slowly revived. |

shot 24. | emblematic shot of dog/hero. |

efforts are continued by the Saint Bernards in shots 9-19. Only in the last two shots of the narrative (22-23) is the family reunited. The extent to which the mother's worrying, shown in shots 6 to 8 and 23, overlaps with the children's struggle in the snow is uncertain, but implicit to the story's construction. The repeated actions of mother and father leaving and entering their house in shots 6 to 8 clearly establish temporal relationships between these three scenes, however, while time is condensed within them. In shot 7, when the mother goes off-screen right and then quickly returns to the house, the spectator understands that she has searched for her children over a longer period of time than she is out of frame. Although the mother's return is followed immediately by that of her husband, considerably more time has presumably elapsed between these events. There is a major discrepancy between real time and screen time within a single shot; and the nature of this discrepancy must be determined by the viewer. It was a combination of representational strategies that Porter had used since Life of an American Fireman .

The narrative is, by later cinematic standards, radically distended as the Saint Bernards romp through the snow for eleven successive shots. For Porter, the scenic beauty of these scenes was paramount, and the narrative was pushed into the background. This emphasis on scenery is consistent with earlier Edison films like Rube and Mandy at Coney Island where the comedy was interrupted by scenic display. The limitations endemic to the construction of a story in Porter's representational system made these nondiegetic digressions all the more important. Slightly more than a year after Lost in the Alps was made, last-minute rescue films were to have a very different construction. Advanced filmmakers like Griffith would take similar material and intercut the children, parents, and dogs in a way that heightened the dramatic intensity of the film. The mother's worrying would have punctuated the rescue rather than appearing before and after it. Under such circumstances the scenic value of the snowy landscape would have become secondary to the suspense generated by the narrative.

Complex Narratives

Porter did periodically rely on complex, unfamiliar narratives. The frequency with which exhibitors facilitated their viewers' comprehension of these films through sound effects, a lecture, behind-the-screen dialogue, and/or informal comments during the screenings is impossible to determine with any accuracy. Although this assistance was offered in some circumstances, it was certainly not offered in all. Porter's most ambitious projects must therefore be looked at from this double perspective. On the one hand, some exhibitors intervened to make complex narratives more intelligible; on the other hand, the films were often exhibited without such assistance and were not readily understood by their audiences. This problem, which faced many filmmakers, was underscored by the Film Index :

MOVING PICTURES—FOR AUDIENCES, NOT FOR MAKERS

Regardless of the fact that there are a number of good moving pictures brought out, it is true that there are some which, although photographically good, are poor because the manufacturer, being familiar with the picture and the plot, does not take into consideration that the film was not made for him but for the audience. A subject recently seen was very good photographically, and the plot also seemed to be good, but could not be understood by the audience.

If there were a number of headings on the film it would have made the story more tangible. The effect of the picture was that some people of the audience tired of following a picture which they did not understand, and left their seats. Although the picture which followed was fairly good, the people did not wait to see it.

Manufacturers should produce films which can be easily understood by the public. It is not sufficient that the makers understand the plot—the pictures are made for the public.[72]

With films such as Life of a Cowboy, Kathleen Mavourneen , and Daniel Boone , it is difficult to determine whether Porter and McCutcheon misjudged their audience's knowledge of these stories, wanted the films to be shown with a commentary, or failed to achieve the level of self-sufficient clarity they originally intended. Certainly the gap between the filmmakers' ambitions and what an audience might reasonably be expected to understand without an exhibitor's lecture is apparent either by contrasting a silent viewing of Life of a Cowboy (May 1906) to a reading of the Edison trade description or comparing this description to a review that appeared in Variety (see documents nos. 21 and 22). For all his praise, Variety's Sime Silverman viewed the first part of the film as a series of discrete incidents like Life of an American Policeman rather than as a unified narrative. While many of the individual situations were immediately recognizable from Wild West shows, the story that held these situations together was not easily discernible.

DOCUMENT No. 21 |

LIFE OF A COWBOY |