Dramatic Changes and an Elusive Goal

Ronan's optimism was short-lived. He soon found himself deeply involved in a new Rockefeller initiative to save the New Haven, New York

[50] The activities leading to the 1961 mass transportation legislation are discussed in Danielson, Federal-Metropolitan Politics, Chapters 3–9. Rockefeller, Meyner, and other state officials were absorbed in working out their own responses to the rail problem, and were not actively involved in the campaign for federal transit-subsidy legislation.

[51] Regional Plan Association, Commuter Transportation, Report Prepared for the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, U.S. Senate, 87th Congress, first session (Washington, D.C.: 1961), and editorial, New York Times, March 27, 1961.

[52] John Sibley, "Report Rejects Rail Agency Plan," New York Times, January 16, 1964.

Central and Long Island railroads—this time through public ownership and operation. In New York State, and in New Jersey as well, government's role in preventing collapse, in stabilizing, and in improving rail and bus service in the region has steadily deepened and widened since the early 1960s. New policies hammered out in Washington have been joined with state programs to alter, sometimes quite strikingly, the organization of transport programs and the criteria for action. Yet the broadest planning and financing goals enunciated by the Regional Plan Association and its fellow regional travelers remain unfulfilled, providing a time-honored banner to be unfurled in the editorial pages of the Times and in RPA bulletins, as the region's mass transit system lurches fitfully into a modest future.

In the following sections we explore the search during the 1960s and 1970s for solutions to the mass transportation problem, concentrating on changes in areal and functional scope of public institutions, and on the ways that leadership skills, funds, and other resources have been concentrated so that public officials could maintain transit services in the New York area. Our main focus is on the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, a 12-county agency established by New York State in 1968. More briefly, we examine efforts to enlarge the Port Authority's role in maintaining trans-Hudson commuter facilities. Intertwined with these activities are the efforts of the federal government, which has played an increasingly important role in financing and shaping public efforts to meet the region's mass transit problems.

Creating a Regional Transit Agency

Despite William Ronan's professed optimism in 1964, it seemed clear that significant new initiatives would be required if the region's commuter rail services were to be kept alive. In the world of the ideal planner, the rational approach might involve combining all major rail and road facilities under one institution, embracing those portions of the region in all three states. In the world of political reality, however, even the innovator with a grand design moves slowly, incrementally, using short-term crises as opportunities to extend his power, then pausing to negotiate with potential opponents who might resist a broader role—until, drawing their fangs or lulling them to unwary sleep, he pounces.

Or, to alter the metaphor: For the political innovator, the adroit use of the "camel's nose" strategy is often the sine qua non of skilled leadership. The "camel's nose" is the first step in a large new government program; being small, it may seem acceptable to legislators and the public, while if the true long-term costs—the entire camel—were seen at the outset, opposition would widen and the first step might never be taken.[53]

The evolution of New York State's role in mass transit between 1964 and 1968 illustrates these political strategies fairly well. The first step was to save the Long Island Rail Road, which had been operating since 1954 under a special program of state aid. For several years public officials lived under the

[53] Planners sometimes oppose the camel's-nose strategy as offensive to their principles (that programs should be based on a rational calculation of long-term costs and benefits), while fiscal conservatives object for different reasons—because the strategy makes it more difficult for them to build a successful alliance against the proposed innovation.

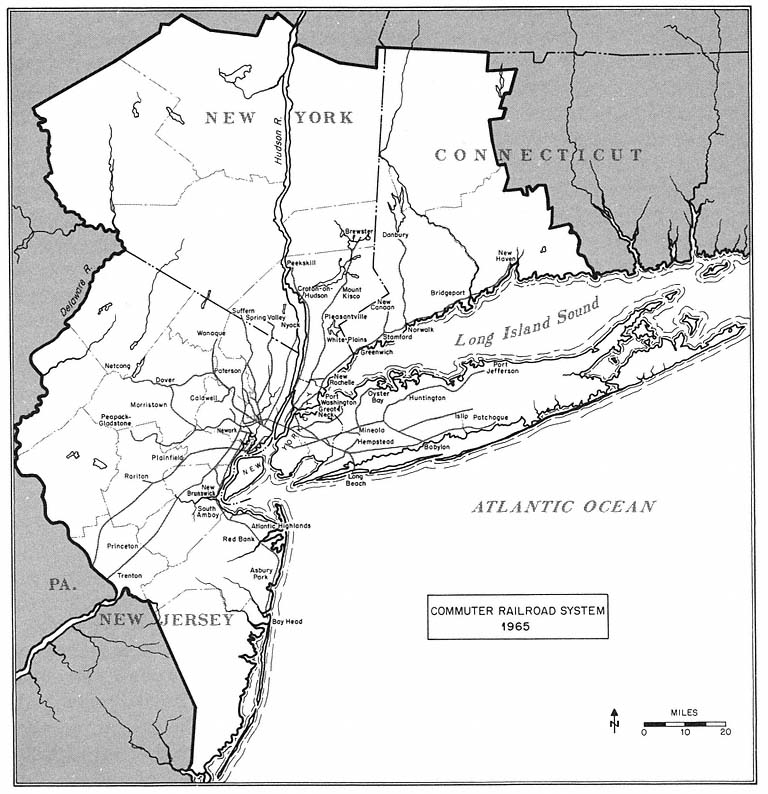

Map 9

hope—or perhaps it was always an illusion—that the LIRR would emerge in 1966 at the end of the twelve-year program as a healthy private rail carrier. Even with tax relief and other concessions, however, the LIRR operated at a deficit or barely broke even in the early 1960s, and the modernization efforts proceeded very slowly.

By 1964, Governor Rockefeller was forced to recognize that more drastic action would be required, and he appointed Ronan, his chief transportation adviser, to head a study committee. Reporting to the governor early in 1965, the Ronan committee recommended that the state purchase the LIRR and create a new public authority (the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority) to operate the rail line and carry out a wide-ranging modernization program. In order to spread the costs, and thus make the plan more palatable to the state legislature, the railroad would be purchased with state funds (but for far less than the "$2 billion in new highways that would be required . . . if the LIRR should cease to exist"), the costs of station maintenance would be met by the counties served by the railroad, and it was hoped that "much if not all" of the

$200 million improvement program would be financed under the federal mass transit program. The camel's nose was not small, but at least there seemed to be several tents. And to avoid objections from the still-influential highway coalition, no mention was made of tapping toll revenues of the Triborough Authority, whose bridges and tunnels directly competed with the LIRR for passengers bound for Manhattan.[54]

Rockefeller had been actively involved in shaping the plan, and he immediately endorsed the report. A bill to create the MCTA was introduced and quickly approved by the state legislature.[55] While the main emphasis of the Rockefeller-Ronan plan was the need to meet the immediate crisis on the LIRR, the bill empowered the new authority to develop plans ensuring the continuation of other commuter rail services in the New York region. The legislation also reflected Rockefeller's interest in exerting strong state leadership in this field. Despite local demands for a role in setting MCTA policy, all five members of the new authority's board were to be appointed by the governor. And the first chairman would be William Ronan.

During the next two years, the state bought the LIRR for $65 million and began negotiations with officials of the New Haven and New York Central, where mounting deficits again threatened the termination of passenger services.

Meanwhile, the financial and the physical condition of the city's subway system continued to deteriorate, demonstrating the limited effectiveness of the 1953 Transit Authority scheme. As Republican candidate for mayor of New York City in the fall of 1965, John Lindsay made the local transportation problem one of his major targets, criticizing past city and state actions, and promising that he would press for coordinated planning and financing of rail and highway developments in the city. Soon after his election, Lindsay had legislation introduced in Albany to extend the Rockefeller-Ronan initiatives dramatically by merging the Transit Authority and Triborough. Lindsay's bill would also give the mayor power to appoint a majority of the new governing board's members.

The Lindsay plan, which promised policy coordination for mass transit and highways, as well as a flow of funds from Triborough to the subway system, was enthusiastically endorsed by the New York Times .[56] It was also

[54] The 1965 proposals are set forth in New York State, Special Committee on the LIRR, A New Long Island Rail Road (New York: February 1965); for a summary of the plan, see Charles Grutzner, "Rockefeller Urges State Buy L.I.R.R. and Modernize It," New York Times, February 26, 1965.

[55] The Ronan committee presented its report to Rockefeller on February 25, 1965 and he released and endorsed it the same day. The MCTA bill was passed by the state assembly on May 20, and by the state senate on May 26; Rockefeller signed the bill on June 1. This and subsequent Rockefeller-Ronan initiatives in mass transportation are discussed briefly in Robert H. Connery and Gerald Benjamin, Rockefeller of New York: Executive Power in the Statehouse (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1979), pp. 274–280. On Rockefeller's leadership style, see especially Chapters 3, 7, and 11. On his relationship with Ronan and his use of public authorities, see also Walsh, The Public's Business, especially Chapter 10.

[56] The enthusiasm of the New York Times is conveyed in its series of editorials: "Mr. Lindsay's Transit Proposal," February 18, 1966; "Transit Debate," March 12, 1966; "Unifying Transport Policy," May 5, 1966; "Time for Transit Action", May 16, 1966; "Who Speaks for Strap-hangers?," May 24, 1966. This "sound program," this "carefully thought-out program for bringing order" out of chaos and aiding the city's "mobility and prosperity," the Times argued in its May 16 and 24 essays, "must not be allowed to die because of special interests and political deals." In a perhaps unintended pun, its May 16 editorial found the Lindsay plan in "grave danger."

condemned, with even greater energy and effectiveness, by Robert Moses, the investment banking community, the automobile associations, leaders of the construction unions (whose regard for Moses and concern for a continuing flow of highway construction jobs were legendary), the existing members of the Transit Authority (whose jobs would be abolished by the Lindsay bill), and Democratic legislative leaders in the state capital.[57]

Against this phalanx, Lindsay's proposal met a quick and bloody death in the state legislature. However, Lindsay's actions exposed and underscored important weaknesses in Rockefeller's leadership. During his first gubernatorial campaign in 1958, and extending through his LIRR purchase plan of 1964–1965, Rockefeller had built a reputation for initiative and vigorous action in meeting mass transportation needs. But behind the rhetoric of leadership, the creation of the MCTA, and its efforts to stabilize commuter service, the reality was troubling. All the commuter railroads in the region and the city's vast subway system were in deep financial difficulties; and federal funds needed to help modernize these rail lines might not be forth-coming in large amounts. Upstate legislators would be wary of pouring more state money into the New York region's transit morass. And now Lindsay's vigorous campaign threatened to displace the ambitious governor as the acknowledged leader—in the Empire State and nationally—in dealing with urban transportation problems.

Meanwhile, Moses sat atop Triborough's surplus: millions of dollars a year that could be used to stabilize and improve rail services—and to bolster Rockefeller's reputation as an innovative problem solver. Moses himself was a contender for leadership; his pronouncements on urban transport always received wide publicity, and even now, in 1966, his engineers were preparing a report on highway and mass transit needs for the New York region.[58] Moreover, the history of relationships between Rockefeller and Moses suggested that Triborough's leader would always maintain a certain unruly independence.[59]

Could these problems be converted into opportunities, enabling Rocke-feller to reassert his central leadership role? The governor thought so, and by the first days of 1967 he was ready to set in motion a three-pronged attack. First, he announced plans to combine state highway activities (then under the Department of Public Works) with mass transport in a new Department of Transportation, symbolizing the need for a coordinated approach. The new agency would then formulate a statewide plan for a "truly balanced" transpor-

[57] The opponents' views are set forth in Samuel Kaplan, "Moses Calls Transit Unity 'Hogwash,'" New York Times, January 8, 1966, Emanuel Perlmutter, "Moses Calls Transit Unity an Illegal, 'Fantastic' Plan," New York Times, February 14, 1966; Emanuel Perlmutter, "City Transit Plan Scored by Travia," New York Times, February 20, 1966; Richard Witkin, "Lindsay and 'the Moses Problem,'" New York Times, March 20, 1966; Charles G. Bennett, "Lindsay Charges Transit Trickery," New York Times, May 14, 1966; Charles G. Bennett, "Lindsay Angers Council With Blunt Transit Talk," New York Times, May 24, 1966; and Moses, Public Works, pp. 899–904. For a detailed analysis of the Lindsay plan and its fate, see Caro, The Power Broker, Chapter 48.

[58] That report, prepared by the Madigan-Hyland engineering company, was released to the press by Moses in March 1967. See Peter Kihss, "Gains in Transit Held Vital Here," New York Times, March 20, 1967.

[59] Ronan also had had his problems with Moses. On the Rockefeller-Ronan-Moses connections, see Caro, The Power Broker, pp. 1070 ff.

tation system. Second, he proposed a $2.5 billion bond issue for "major capital investments in mass transportation systems" and highway arteries. Sensitive to upstate interests, his message to the legislature emphasized that these billions would meet "urgent needs . . . in the rural areas, the towns, the villages, the suburban and city areas of our state." Buses as well as rail lines would be aided by the state's program. And to meet the concerns of influential northern legislators, a Niagara transportation authority would be created to organize transport improvements in the northwestern portion of the state.[60]

The third part of Rockefeller's program incorporated the Lindsay proposal to combine Triborough and the Transit Authority and added the MCTA to create a new Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). In urging that the MCTA be broadened to include both of the city agencies, the governor emphasized that this would assure "unified regional policy direction."

A central element of Rockefeller's plan, as it had been of Lindsay's, was the capture of Triborough's surpluses to subsidize mass transportation. The challenge was to overcome the legal and political obstacles that stopped the Lindsay scheme in 1966, and that had sharply limited access to Port Authority surpluses in the 1962 covenant. Rockefeller's advisers thought they could see a route to legislative approval—if a way to protect the bondholders could be devised, and if Moses could be persuaded to approve the new plan, thus muting opposition from the banking community, and from Moses's allies in the construction unions and the automobile associations.[61]

Moses was no longer a young man. In December 1966 he had celebrated his seventy-eighth birthday. He had resigned, or in a few cases been removed from, most of his many city and state positions; Triborough was his final remaining official position of real influence.[62] If he viewed the merger as ending his public career, he could be expected to attack, vigorously and adroitly, and it might then not be possible to obtain agreement to the plan from legislators and bondholders.[63] So Rockefeller and Ronan moved cautiously and shrewdly: They pointed out to Moses and his associates that a future record of achievement lay not simply with Triborough, whose successes were in the past, but in exerting leadership in creating a magnificent new structure—a Long Island Sound bridge. But Moses could not take on that

[60] See Richard L. Madden, "Governor Offers $2-Billion Plan in Highways and Unified Transit," and "Text of Governor's Proposals for Action in His Ninth Message to the Legislature," New York Times, January 5, 1967; Ronalo Maiorana, "Governor Asks 2.5-Billion for Transport Programs," and "Text of Rockefeller Message on a Huge Bond Issue for Transportation," New York Times, January 29, 1967.

[61] For evidence on the views and strategy of Rockefeller's advisers, see Melvin Masuda, "The Formation of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority of New York State," senior studies paper, Yale Law School, April 1968, pp. 35 ff.

[62] In the spring of 1965, Mayor Lindsay had removed him as City Construction Coordinator, which had been a central position in negotiations for state and federal highway funds. On his departure from other positions, see Caro, The Power Broker, Chapters 46–49.

[63] Caro indicates that Moses had calculated the interest payments state taxpayers would have to underwrite for the $2.5 billion issue (they totalled $1 billion); and he had analyzed the possibility that, as Ronan argued, the Triborough surplus would completely offset the subway and LIRR deficits—and concluded that the surpluses wouldn't even come close. Moses was ready to make these figures public, and the governor realized they could be devastating, especially to upstate voters. See Caro, The Power Broker, pp. 1134–1137.

challenge unless Rockefeller pressed for legislative approval and appointed Moses to head the project. Meanwhile, Moses was led to believe that he would be appointed to an important post with the MTA—as a member of the new authority's board, or perhaps as president of Triborough, which would retain its organizational identity though not policy control.[64]

Moses accepted these assurances. After a meeting with the governor in March 1967, he publicly supported the merger bill, and he endorsed and campaigned for the $2.5 billion bond issue.[65] The construction unions followed his lead. Meanwhile, Rockefeller had won Mayor Lindsay's support by offering some minor concessions to meet the mayor's reluctance to accept a new state-controlled authority with great influence in local affairs.[66] Having no significant opposition, the bond issue and merger bills were overwhelmingly approved by the state legislature by the end of March. And, with a slight majority upstate and an overwhelming favorable vote in New York City, the voters endorsed the highway-transit bond issue in November.[67]

The only obstacle remaining in the way of the Rockefeller-Ronan scheme was approval by the bondholders. Rockefeller had already persuaded Moses not to oppose a negotiated settlement. In a series of discussions with representatives of the bondholders during the winter of 1967–1968, it was agreed that the bondholders would accept the merger and the control of Triborough surpluses by the MTA board, in return for a modest increase in the bondholders' interest payments.[68]

On March 1, 1968, the new Metropolitan Transportation Authority came into being, with William Ronan as chairman and chief executive officer, and with eight other members. Robert Moses was not among them. Instead, Robert Moses was designated as "consultant" to Triborough. As he recalled later, "I was told by Dr. Ronan and by Governor Rockefeller several times that the building of the Long Island Sound crossing . . . would be my primary responsibility when that project was in the clear." Meanwhile, he was left with "rather undefined duties," and his former assistants now reported directly to

[64] See Moses, Public Works, pp. 256–258, and Caro, The Power Broker, pp. 1138–1139.

[65] Previously, Moses had attacked the merger plan as "absurd" and "grotesque"; see John P. Callahan, "Moses Denounces a Transit Merger," New York Times, January 22, 1967. Even after campaigning for legislative approval of the plan, Moses could not resist expressing his hostile views toward integrated transport financing and his skepticism that a merger would provide any real assistance in meeting the new agency's rail deficits. In a report released during the summer of 1967, he and his fellow Triborough commissioners proclaimed: "There is no surplus available now or in the foreseeable future for any extraneous municipal purpose such as the rapid transit operating deficiency." Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, Financial and Construction Program, 1967–1971 (New York: July 1967), p. 1.

[66] The main concession was that three of the gubernatorial appointments to the nine-person MTA board would be individuals recommended by the mayor of New York City. See Masuda, "The Formation of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority," pp. 46–53, for a review of the Lindsay negotiations.

[67] The favorable vote was 69 percent in New York City, 52.5 percent in the nearby counties (Nassau, Suffolk, and Westchester), and 51 percent in the rest of the state. See Masuda, "The Formation of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority," p. 58.

[68] Payments were increased by one-quarter of one percent. It was perhaps helpful to the governor's cause that the central position in negotiating for the bondholders was held by the Chase Manhattan bank, whose president was Nelson Rockefeller's brother, David. On the negotiations, see Masuda, pp. 59–60, and Caro, The Power Broker, pp. 1140–1141.

Ronan's office.[69] And as the possibility of building the Long Island Sound bridge faded and died in the 1970s,[70] so did Moses's dream of constructing a final spectacular contribution to the road-building era that now seemed no more.

So the camel advanced by increments into the tent, and the old tiger was squeezed into a corner, and finally sent out into the dark.[71]

Larger Resources and a "Grand Design"

What painstaking negotiations, shrewd maneuvering, and broader vision had created in the spring of 1968 was a public enterprise with many of the attributes long sought by advocates of coordinated transport and regional planning. The MTA spanned a large part of the region—New York City plus seven nearby counties, a total of 4,000 square miles in which lived twelve million citizens.[72] It was responsible for subways, buses, commuter rail services, and vehicular bridges and tunnels, and the new agency had a statutory mandate to implement a "unified" mass transportation policy for the region. Moreover, its leaders had a tilt toward rail facilities. Ronan criticized previous public policies that had "permitted our rail links to atrophy," and promised to seek a "balanced approach" in order to "save, then nurture and restore the great vitality of our troubled cities."[73] The MTA's scope and perspective made this a "tremendous forward step," commented the New York Times editorially. The Times view that this was "the greatest advance in the metropolitan transportation system in at least half a century" was no doubt received warmly at the governor's mansion in these early months of a presidential election year. The newspaper was compelled to note, however, that with New Jersey not yet included, the "truly regional agency that has been the goal of planners for decades" was yet to "evolve."[74]

The new agency not only had wide regional and transportation scope; MTA also had money—millions of new dollars that could be used to revitalize rail and bus services, and thus stabilize traffic or even reverse the trend toward the automobile. The largest chunk of new money came from the bond issue approved in the fall of 1967; together with local matching funds, this would provide more than one billion dollars during the next five years for

[69] The quotations are from Moses, Public Works, pp. 257–258. Ronan later commented expansively to associates that he had never intended to give Moses any power at the MTA.

[70] See Chapter Four in this volume.

[71] Yet he remained not without hope, however slim. In December 1975, more than two years after Rockefeller had withdrawn his support for the crossing, Triborough staff updated their calculations of the cost and debt service required for the bridge; and when one of the authors visited Mr. Moses in the fall of 1978, shortly before his ninetieth birthday, he set forth with moderate passion the need for the project, and they viewed a slide show noting the decline in economic growth on Long Island and describing the anticipated benefits of the new bridge—more than 50,000 new jobs generated by improved access from Long Island to the mainland, and lower levels of traffic congestion and therefore of air pollution in the northeast quadrant of the region.

[72] The seven counties outside New York City are Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, Rockland, Dutchess, Orange, and Putnam.

[73] Ronan, "Regional Transportation," an address to the Canadian Transit Association, June 25, 1968.

[74] "As the M.T.A. Takes Over," editorial, New York Times, February 16, 1968.

transportation improvements planned and carried out by the MTA.[75] In addition, Ronan could draw upon the surpluses of Moses's Triborough empire, which were expected to be more than $25 million in the first year, with larger sums to follow.[76]

Equally important, the MTA had leadership skills and political savvy that seemed likely to rival those found earlier in the Moses regime and at the Port Authority. William Ronan had already proven to be an intelligent, forceful, and crafty adviser and executive—in his many years as a top aide to Governor Rockefeller, in his negotiations leading to the creation of the MCTA, the purchase of the LIRR, and the deposing of Moses, and in his nearly three years as chief of MCTA. And behind Ronan stood Rockefeller, whose interest in a vigorous and successful MTA was quickened by his awareness that the agency's early efforts could enhance his political power as governor, and perhaps improve his prospects for a successful presidential bid.[77] He had already fought long and hard for creation of the MCTA and the MTA, and had campaigned across the state for the 1967 bond issue. In contrast with the approach in the 1950s of Governor Dewey and New Jersey's Governor Meyner—who fought mainly to keep the mass transit problem at arm's length—Rockefeller wanted to be involved, and he wanted success.

These advantages were, however, offset by obstacles that might interfere with MTA's effort to achieve specific development goals. First, Ronan confronted a wide range of constituency demands, and some of those constituencies were in conflict with one another. There was the potential conflict between the advocates of better rail and bus facilities, and those who might demand better highway facilities or lower tolls. Even those who favored better bus and rail transit could not be counted on to support the MTA's efforts. Some of its proposals would probably aid certain parts of the region more than others, and the "others" could be expected to protest.

Moreover, among hundreds of thousands of MTA clients were many—and generally the most outspoken—whose basic orientation to the services the authority would provide was hostile and aggressive. In addition, MTA's insulation from local policy control—only New York City was represented on the authority's board—meant that elected officials from Nassau County and other local areas would adopt commuters' concerns as their own, attacking the

[75] Ronan estimated that $600 million from the $2.5 billion could be allocated to MTA transit improvements; to that he added $200 million from New York City (required as matching money on a 3:1 basis), plus $100 million per year which the city had regularly been allocating from its capital budget. See "State Bonds Due to Help City Transit," New York Times, November 27, 1967.

[76] Moses objected to these plans to drain off large amounts from Triborough, noting initially that the available surplus would be no more than $5 million a year, and later agreeing that larger sums could be obtained, but only by halting current authority plans. How could a third Queens Midtown tunnel and other needed improvements be carried out, Moses lamented, if the Triborough surplus, "honestly earned and prudently husbanded," was to be diverted to rail? By 1970 he found this policy "political folly" and asserted that Triborough's "program of expansion is dead. Future public needs are ignored. It has become another routine, static, bureaucratic agency. The original proud concept has been compromised. . . . " Moses, Public Works, pp. 259–261.

[77] As Richard Witkin commented, dramatic transportation projects might add to Rocke-feller's "political luster" and thus aid his "non-candidacy" for the U.S. presidential nomination. Witkin, "$2.9-Billion Transit Plan for New York Area Links Subways, Rails, Airports," New York Times, February 29, 1968.

agency for its neglect of local needs.[78] The prospect for such conflict was enhanced by the Albany-approved arrangement for meeting station maintenance costs on the LIRR: the state-run authority would maintain the railroad stations, but it would charge the local communities for these costs. As the experience of the MCTA under this arrangement already revealed, these mandated expenses did not endear the agency to local officials who had to levy taxes to pay the bills.[79]

And there was, really, a problem of money. Certainly, the new authority had the great advantage of the 1967 bond funds, and a pot of Triborough gold that might increase. But more would be needed simply to meet the increasing subway and commuter-railroad deficits, fueled regularly by wage settlements beyond the means of the operating agencies. And still more money would have to be found to demonstrate that the MTA was a successful invention—not merely an agency battling to stay even, but an enterprise that could produce striking plans, marshal public opinion in support of its vision of the future, experiment with new technologies, and reconstruct the region's transport systems. The MTA's leaders were not unaware of these greater financial needs, and soon after the MTA commenced operations Ronan began to urge that "full national resources be applied" to solving urban transportation problems.[80]

First, however, if the new authority wanted to dramatize its new role, convert skeptics and adversaries into admiring supporters, and demonstrate how massive funds would be used, Ronan needed a plan. MCTA's planning skills were set to the task, and in February 1968, before the MTA was formally in being, Rockefeller and Ronan announced a "sweeping $2.9 billion blue-print." Their self-styled "Grand Design" called for a new subway under Man-hattan's Second Avenue, running north to connect with a new subway line in the Bronx, as well as additional subway and LIRR service in Queens, a new rail tunnel from Queens to Manhattan at 63rd Street, and a new rail terminal in Manhattan at 48th Street. There would be a rail line built to Kennedy Airport, and hundreds of new subway cars and commuter railroad coaches for the region's rail travelers. New turbo-trains would rush Long Island commuters at speeds up to 100 mph, cutting in half commuting time from major

[78] As originally constituted, the MTA board included nine members, all appointed by the governor. Three of the nine were to be appointed "only on the written recommendation of the mayor of the city of New York"; there were no provisions for recommendations or other formal involvement of the seven suburban counties with MTA facilities—Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, Putnam, Dutchess, Rockland, and Orange counties. In the 1970s, in response to suburban complaints of underrepresentation, the board was restructured several times. By 1979, it had been expanded to thirteen members, chosen as follows: (1) the governor appointed four on recommendation of the mayor of New York City; (2) the county executives of the seven suburban counties each submitted a list of three names, from which the governor selected four members—one each from Nassau, Suffolk, and Westchester, and one from the remaining four counties; and (3) the governor appointed the chairman and the four other members, two of whom must be New York City residents.

[79] Upon receiving the MCTA bill for the year ending in March 1967, for example, New York City's controller, Mario Procaccino, opposed paying $3.8 million of the total of $4.4 million; the Nassau County executive declared that "under no circumstances" would his county pay its $1.8 million bill; while Suffolk's executive expressed "shock" at its $900,000 MCTA bill, and said he would turn the matter over to the county attorney. See Charles G. Bennett, "Procaccino Calls Rail Bill Too High," New York Times, June 20, 1967.

[80] See speech by Ronan, "Regional Transportation," June 25, 1968.

suburban stations. And true to Rockefeller's promise and Moses's dream, one or even two bridges would extend across the Long Island Sound.[81]

Upon hearing Ronan describe these visions of the future, Rockefeller stepped to the front of the assembled audience of journalists and exclaimed that he thought "we have been witnessing a historic event." The New York Times was less enthusiastic, for while the plan seemed basically "well-conceived," it "will not remedy all the existing deficiencies." The Times argued that "something akin to a system of moving sidewalks" might be added to the plan, for the enjoyment of the more agile mid-Manhattan office workers. Buried in the extensive news coverage given to the media event was a cautionary note from chairman Ronan, who said that all the cost figures had been calculated at current price levels, and that any delays might increase costs "beyond our capacity to meet them."[82]

"Many a Slip . . . "

During the next decade, progress toward the "Grand Design" proceeded by fits and starts, with a bit more of the former than the latter. Although the ten-year plan was endorsed by the Regional Plan Association and other civic groups, the program came under fire from Mayor Lindsay, from elected officials in Queens and Brooklyn, and from spokesmen for the New York Stock Exchange and other groups—either because it did not go far enough, or because it slighted some parts of the city while benefiting others.[83]

Meanwhile, the subway deficit continued to rise, from $49 million in 1968 to more than $70 million in 1969 and $120 million in 1970, bringing pressure on Ronan and his MTA board to increase the transit fare, which they did in 1970. Further wage increases and larger deficits led to another fare increase in 1972. On each occasion, city officials and strap-hangers attacked the MTA for the fare hikes and continuing service deficiencies.[84] Long Island

[81] Ronan and his aides estimated that these projects—except perhaps for the two Sound bridges—would be completed within ten years. The second phase, beginning in 1978, would see still further rail improvements and new transportation centers throughout the suburbs. The MTA plans are described in Witkin, "$2.9-Billion Transit Plan for New York Area Links Subways, Rails, Airports," and Charles G. Bennett, "Transportation Funding Would Have 4 Sources," both New York Times, February 29, 1968, and in MTA, Transportation Progress (New York: December 1968), pp. 16–27.

[82] See Witkin, "$2.9-Billion Transit Plan," and "Program for Better Transit," editorial, New York Times, June 5, 1968.

[83] Brooklyn officials argued that the program gave "inadequate attention" to that borough, and gave too much attention to "carrying suburbanites into and out of Manhattan." City business leaders expressed "dismay" that part of the Second Avenue subway was to be deferred until stage two of the program. Queens representatives urged that more rail lines be provided in their area. In response, the Board of Estimate and Mayor Lindsay agreed to aid these projects with $500 million in additional contributions from the city—the new funds to be raised through long-term borrowing. See Charles G. Bennett, "Ronan Warns City To Act on Transit Lest Funds Shrink," New York Times, August 13, 1968; Seth S. King, "Ronan Willing to Expand Subway Plans, and 'Happy' City Pays," New York Times, September 20, 1968.

[84] In 1970, for example, Mayor Lindsay denounced the MTA and appointed a "transit watchdog" committee, "fare-dodging strikes" were carried out by groups of commuters, and several Queens officials, led by the Queens district attorney, announced an inquiry to determine whether fare increases were the result of a "criminal conspiracy." Edward C. Burks, "Lindsay Rides Subway; Calls It 'Unacceptable,'" New York Times, January 10, 1970; "Transit Return to City is Sought," New York Times, February 2, 1970.

rail commuters, faced with work slowdowns and deteriorating equipment in the first years of the MTA, were equally unhappy.[85]

But Ronan and Rockefeller fought back, with substance and with public-relations ploys. In the fall of 1968 the first new LIRR cars were delivered, and the governor announced enthusiastically that "the future in metropolitan area transportation is here now."[86] Less than a year later, as heightened labor problems and service breakdowns resulted in the LIRR's "worst service in the memory of man,"[87] and as commuters revolted against showing their tickets and paying fares, Rockefeller promised that the LIRR would have "the finest railroad service in the country" within two months. Sixty days later, to a skeptical audience, he announced that this pinnacle had been achieved. It was, as one observer noted, "one of a long list of political productions" by the embattled governor.[88] Meanwhile, Nassau County and New York City continued to withhold station-maintenance payments, wages spiralled upward, and deficits on the LIRR and the subway system grew ever larger.[89]

Still the MTA inched forward with its modernization plans. By 1971, 620 new cars were in service on the LIRR; and during 1968–1971 1,100 new subway cars, most of them air conditioned, were purchased using funds from the 1967 bond issue and placed in service. Also in 1971, the Staten Island rapid transit line was purchased for a fair market price—one dollar—and the MTA began to replace its ancient rolling stock (none had been bought since 1925) and refurbish its decrepit stations. Meanwhile, Connecticut had created a Transportation Authority to work with the MTA to maintain passenger service on the bankrupt New Haven Railroad. The two state authorities assumed full responsibility for commuter service on the line in 1971 and began a $100 million modernization program—with federal funds totaling $40 million to assist the bistate effort. The following year, the MTA took over the remaining commuter lines operating out of Grand Central Station, the Hudson and Harlem routes through Westchester County formerly provided by the New York Central.[90]

Moreover, Ronan's agency—now dubbed the Wholly Ronan Empire—began to move vigorously on bus problems, a concern that had simply been left out of the original "Grand Design."[91] In 1971, 200 new buses were put into

[85] See, for example, "G.O.P. Unit Assails Service on L.I.R.R.; Change Is Proposed," New York Times, October 9, 1968, and sources cited below in note 88.

[86] Quoted in MTA, Transportation Progress, p. 13.

[87] This was the assessment of three transportation specialists with extensive experience in the region: Joseph M. Leiper, Clarke R. Rees, and Bernard Joshua Kabak, "Mobility in the City," in Lyle C. Fitch and Annmarie Hauck Walsh, eds., Agenda for a City (Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage, 1970), p. 389.

[88] See Craig R. Whitney, "With Day to Go, L.I. Riders Are Wary," New York Times, October 6, 1969; Bill Kovach, "Governor Hails L.I.R.R.," New York Times, October 8, 1969; Richard Witkin, "On Stage: Transport," New York Times, October 8, 1969.

[89] See, for example, Robert D. McFadden, "L.I.R.R. Reports $16-Million Loss," New York Times, December 23, 1969; Lesley Oelsner, "Long Island Railroad Faces $43.3-Million Deficit," New York Times, January 5, 1971; Robert Lindsey, "Transit: Ink Gets Redder," New York Times, March 8, 1971.

[90] The details are contained in the MTA's reports. See, in particular, MTA, 1971 Annual Report (New York: March 1, 1972), pp. 19–41; MTA, 1968–1973: The Ten-Year Program at the Halfway Mark (New York: Undated, ca. June 1973), pp. 9–12, 18–53.

[91] An early use of the phrase "Wholly Ronan Empire" is found in Sydney H. Schanberg, "Ronan Lays Transit Crisis To a 30-Year Lag in City," New York Times, August 25, 1968. Cf. Fred C. Shapiro, "The Wholly Ronan Empire," New York Times Magazine, May 17, 1970, pp. 34–52.

service on the MTA's routes in New York City. When several private bus companies in Westchester began to falter financially, the authority and the county government purchased the buses and assured the continuance of commuter bus service. And the MTA responded to a similar problem in Nassau County by creating a new subsidiary, the Metropolitan Suburban Bus Authority, which took over the facilities of ten bus companies and began operating them as a unified system.[92]

While these efforts to stabilize and modernize service went forward, deficits continued to mount on all the MTA's rail systems. The rate of increase on the Long Island was particularly striking, growing from $2.5 million in 1965 (the year before state purchase) to $54.7 million in 1971. In response, the authority raised commuter rates and subway fares, squeezed increasing amounts out of Triborough, and—as inflation ate into the funds remaining from the 1967 bond issue—saw its ability to achieve the "Grand Design" fading.

If more funds were needed, Rockefeller and Runan concluded, the voters would have to supply them through another bond issue. The governor took the lead, carrying the issue to the electorate with a $2.5 billion proposal in 1971—and he was defeated. Undaunted, Rockefeller put together a massive $3,5 billion bond issue two years later, and it too lost in the statewide vote. Both proposals had been carefully crafted to provide large amounts for mass transit and for highways, and Rockefeller offered the prospect of lower bus fares, as well as rail and bus capital improvements. Thus the bond issues might appeal both to advocates of mass transit and auto travel, and to citizens in upstate regions as well as to New York-area voters. But upstate, the proposals seemed to offer too much for New York City and its suburbs, while downstate transit advocates denounced them as "highway plans in mass transit clothing."[93]

So the MTA limped along, with little money to carry out its large construction program, searching for ways to make modest improvements in rolling stock and to meet ever-growing deficits. Triborough tolls were increased in 1972 and again in 1975 to provide funds for rail and bus operations. Although these increases led to some traffic diversion to toll-free bridges, net revenue from the Triborough facilities continued to rise. TBTA funds transferred to mass transit operations doubled to $50 million a year in 1972, rose to $74 million in 1974, and passed $100 million in 1976.[94]

[92] See MTA, 1968–1973, pp. 5, 7, 17, 47–48.

[93] The quoted characterization is that of Theodore W. Kheel, who led the successful campaigns against the 1971 and 1973 bond issues. His point was that every dollar of state funds used for highway construction would generate nine dollars of federal aid, while state dollars spent for mass transit would yield much smaller amounts of federal funds. As a result, even a 60–40 state bond issue (the ratio in favor of transit in the 1973 referendum) would generate more total dollars for highway construction than for transit improvement. For the views of Kheel and others, see Francis X. Clines, "Governor Asking 3.5-Billion Bonds for Transit Plan," and Frank J. Prial, "'New' Transit Plan Isn't," both in the New York Times, July 21, 1973. The campaigns for the two bond issues were covered extensively in the Times during the summer and fall of 1971 and 1973. For useful summaries of the issues, see Frank Lynn, "In New York: Everybody Was for the Bond Issue Except the People," New York Times, November 7, 1971, and Edward C. Burks, "Transit-Bond Plan Termed an Underdog in Need of Heavy City-Suburban Vote," New York Times, November 4, 1973. On the evolving resistance to highway construction, see Chapter Four in this volume.

[94] Triborough's contributions are summarized in MTA, 1975 Annual Report (New York: undated, ca. April 1976), pp. 18–19, and Annual Report—1976 (New York: undated, ca. July 1977), pp. 22–23. In 1974, New York State also began to make direct contributions to meet operatingsubsidies, through a new program to assist rail and bus operations under the MTA and elsewhere throughout the state. See New York State, Department of Transportation, Annual Transportation Report: 1975 (Albany: undated, 1976), pp. 4–5.

The Interweaving of Federal and Regional Action

Faced with mounting transit deficits, Ronan and other officials in the region called upon Washington for help. In his first months at MTA, Ronan advocated tripling federal aid for mass transit projects from its 1968 level of $175 million. He also urged that federal funds for mass transit cover 90 percent of costs as they did in the interstate highway program. MTA was a prominent member of the transit coalition that pressed successfully for passage of the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1970, authorizing several billion dollars for capital projects. By 1971, as president of the Institute for Rapid Transit, a national pressure group, Ronan was among the leaders in lobbying for federal operating subsidies for rail and bus lines, and for use of the Highway Trust Fund to finance transit operations.

In 1972–1973, the MTA was an active member of the national coalition that finally breeched the wall, as the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973 permitted use of trust fund dollars for mass transit projects. The 1973 act also increased federal transit grants to $6.1 billion, and improved the federal matching ratio to 80–20.[95] A year later—spurred in part by energy-conservation arguments—Congress agreed for the first time to provide money for transit operating subsidies, and approved an $11.8 billion multiyear package for mass transportation. The new measure, passed overwhelmingly with bipartisan support, was heralded by members of Congress from the New York region, who had led the fight for approval, as ushering in a "new era for mass transit."[96]

But in MTA territory the new era looked very much like the old, as rail-system deficits continued to mount, and construction for new subway lines crept along slowly. One notable difference, however, was the absence of the old leaders: In December 1973, after nearly fifteen years at the helm in Albany, Nelson Rockefeller had resigned the governorship, leaving soon after for Washington as the third in the 1970s parade of Republican vice-presidents. And in 1974, William Ronan moved from MTA headquarters to the heights of the World Trade Center, as the new chairman of the Port Authority's governing board.

[95] Some of Ronan's activities on behalf of the coalition seeking more federal funds, and the increasing role of federal moneys in MTA projects, are described in Edward A. Morrow, "Heavier U.S. Aid Asked for Transit," New York Times, September 12, 1968; MTA, 1971 Annual Report, pp. 6, 9, 16, 33–38 passim; and MTA, 1968–1973, pp. 16, 73–77.

[96] The quoted phrase is that of Representative Joseph G. Minish (Democrat of New Jersey), who led the battle for approval in the House. Other prominent supporters of the bill were Representative Hugh L. Carey (Democrat from New York City), who had just been elected Governor of New York and vowed to use the new funds to help save the 35-cent subway fare, Representative Edward I. Koch (also Democrat from New York City), whose support for transit aid would later be helpful in his successful campaign to become mayor of New York City, and Democratic Senator Harrison Williams of New Jersey, who once again guided a transit bill successfully through the upper house. The measure also attracted Republican support, with President Gerald Ford urging passage as a "responsible step in our efforts to reduce energy consumption and control inflation." See Martin Tolchin, "House Approves $11.8-Billion Aid for Mass Transit; Measure Now Goes to Ford," New York Times, November 22, 1974.

Meanwhile, the search for additional funds for mass transit continued. In 1973, Mayor Lindsay sought to reduce the $100 million annual burden imposed on the city budget by the transit system by urging a regional payroll tax. Lindsay's scheme involved creation of a regional transit district encompassing the tristate area; the new district would draw funds from federal and state sources, as well as from a payroll tax, thus putting the region's transit operations on a "firm and durable financial footing." Three years later, the MTA's new chairman emphasized the authority's need for "adequate and assured financing on a long-term" basis, and also urged that a broad-based regional tax be enacted.[97]

These sentiments released a predictable flow of encouragement from the New York Times . One commentator on political affairs wrote optimistically that

New York and its surrounding communities have come to realize, more and more, that the suburbs and the city are one—that if New York dies, Scarsdale and Montclair and New Canaan may be next. . . . The regional approach is, perhaps, the only approach.[98]

Eloquent statements indeed. But wary local officials and state legislators had no interest in that kind of regional cooperation, and both the Lindsay and MTA proposals died aborning.

Cooperative action did continue, however, directed toward the goal of squeezing more funds from the occasionally reluctant guardians of the federal exchequer. In 1976, urban interests in Congress obtained additional "temporary" federal funds for commuter rail transportation, in order to "assist in an orderly transition to locally supported service." No such transition had occurred by the fall of 1977, and President Carter reluctantly signed a bill extending this aid, while expressing disappointment that "the affected cities have not yet arranged to live within these original Federal emergency payments."[99] Congressmen from the New York region pressed ahead, urging an increase in the federal gasoline tax, with the added moneys used to provide a new trust fund—for mass transportation programs. And Carter's own proposals, announced in January 1978, called for $50 billion for mass transportation and highways, with matching funds for transit finally reaching the 90–10 ratio used for interstate roads, and with increased flexibility for cities to select their own preferred mix of rail and highway projects. As approved by Congress and signed by the President in November, the Surface Transportation Act of 1978 provided nearly $14 billion for mass transit during the next four years, plus additional funds, if highway projects were

[97] The Lindsay proposal, reminiscent of the 1958 MRTC district plan, is described in Frank J. Prial, "Lindsay Suggests Plan for Transit to Reduce Fares," and in "Excerpts From Lindsay's Plan," New York Times, April 30, 1973. Ronan's successor at MTA, David L. Yunich, set forth his support for a regional tax in his letter of transmittal accompanying the authority's annual report; see MTA, 1975 Report, p. 2.

[98] Frank J. Prial, "Mass Transit: Some Help From the Neighbors?" New York Times, May 6, 1973.

[99] The quoted phrases are from President Jimmy Carter's statement upon signing HR 8346; see "Statement by the President," November 16, 1977.

"traded in" for transit, that might yield a total transit-aid figure of more than $16 billion.[100]

The MTA's First Decade

In announcing the "Grand Design" in 1968, MTA leaders had said that Phase I would be entirely completed in ten years—if there were no delays. But delays there were, due to conflicting priorities among MTA, New York City, and suburban officials, between mass transit and highway proponents, between upstate and downstate voters. By 1978, there were significant improvements in the quality of rail and bus service in the 12-county MTA region, but there were important offsetting minuses as well—fares that had risen sharply, and inaction on most of the new lines that had been proposed in 1968.

On the positive side, the deterioration in the region's commuter services had been halted, and significantly reversed on some rail lines. The Staten Island line now had new rolling stock in place of its forty-five-year-old cars, the subway system and the Long Island rail system had more than 600 new cars each, and the New Haven, Hudson, and Harlem lines also sported new commuter cars and other modest improvements. Bus services in the region were stabilized, and in Nassau County the MTA's efforts had reversed the long-term decline in ridership.[101]

On the other hand, in order to meet continuously rising costs, fares had increased substantially since 1968. Although such increases affected rail and bus services throughout the region, the rate of increase was particularly notable on New York City's subway and bus lines, where fares rose from twenty cents to thirty, then thirty-five, and then fifty cents, bringing agonized cries from riders and local officials.

Moreover, while electrification, air conditioned cars and other improvements had some favorable impact on service quality, they did not meet the expectations of commuters, or even of MTA and state leaders. Here the "loss leader" was the Long Island Rail Road. In the late 1960s, Ronan and his aides had distributed to LIRR commuters their plans for the coming decade—including a table showing dramatic reductions of 40 to 50 percent in running time between Long Island stations and Manhattan. But in 1978, the actual timetables were essentially the same as a decade earlier, and some trains even took longer to reach Manhattan.[102] In the summer of 1978, equipment failures

[100] On these developments in Washington, see for example Edward C. Burks, "U.S. to Open Hearings on Rail-Transit Bill," New York Times, July 25, 1977; Ernest Holsendolph, "White House May Let Cities Decide on Transit Funds," New York Times, November 25, 1977; Albert R. Karr, "Mass Transit Gets Short Shrift," Wall Street Journal, December 30, 1977; Message of the President, January 26, 1978; Terence Smith, "Carter Calls for $50 Billion Highway Program With Increased Share for Mass Transit," New York Times, January 27, 1978; Edward C. Burks, "Howard, Roe Say Carter's Transit Bill Does Not Allot Enough Funds for State," New York Times, February 6, 1978; Edward C. Burks, "Carter Signs a Record 4-Year, $51 Billion Bill for Roads and Transit," New York Times, November 8, 1978.

[101] See MTA, Annual Report—1976, pp. 6, 12–13, 17, and MTA, Annual Report—1977 (New York: January 1979), pp. 6–19.

[102] Based on a comparison between the MCTA's original table, distributed in 1966 or 1967, and LIRR timetables in use in July, 1978. A study of LIRR running times, comparing 1903 and 1976, indicated that in general rail travel between Long Island stations had been faster in 1903 than in1976. See Irvine Molotsky, "Audit Disputes L.I.R.R. On-Time Records," New York Times, November 18, 1978.

A typical story circulating among LIRR travelers in the 1970s was the following bit of gallows humor: Seeing a man lying on the LIRR tracks, apparently bent on suicide, a rescuer rushes forward and then notices a loaf of bread in the man's hand. "Why the bread?" he asks. "I was afraid," replies the would-be suicide, "that I might starve to death before the train comes along."

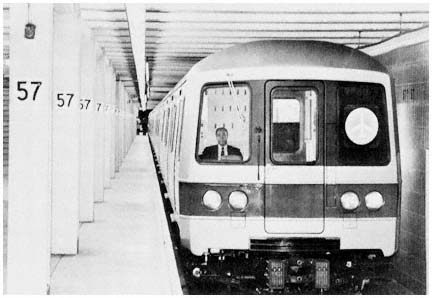

One of MTA's new subway cars operating on the

express line between mid-Manhattan and Kennedy Airport.

Credit: Metropolitan Transportation Authority

and canceled trains had begun to cause political problems for Governor Carey, as they had for his predecessor. Under pressure from the governor—whose spokesman said the railroad was in "hideous shape"—and from commuter groups, the MTA abruptly fired the LIRR president in late July. By general agreement, the LIRR was "in the throes of its worst performance since 1968."[103]

As the energy crisis grew in the late 1970s, the subways, buses and railroad lines of the MTA all experienced significant gains in ridership. But these gains, which continued into the 1980's as gasoline prices remained high, brought as many problems as benefits. MTA revenues were up; but overcrowding became severe, with hundreds of rail commuters standing during long trips from distant suburbs. The added passengers contributed to the increased delays, and at times trains bound for Manhattan were so crowded that they could not pick up passengers at the final inbound stations, leaving

[103] The shape of the railroad, and Governor Carey's political concerns (his opponent was reportedly "relishing the opportunity" to use the LIRR's problems "as a weapon" in the fall campaign) are described in E.J. Dionne, Jr., "Carey Dismisses L.I.R.R. President, Naming a Grumman Aide to the Job," New York Times, July 29, 1978; Robert D. McFadden, "Commuter Groups Offer Advice to New L.I.R.R. Chief," New York Times, July 30, 1978; Irvin Molotsky, "New L.I.R.R. Head Says He Can Be Its Moving Force" New York Times, November 27, 1978.

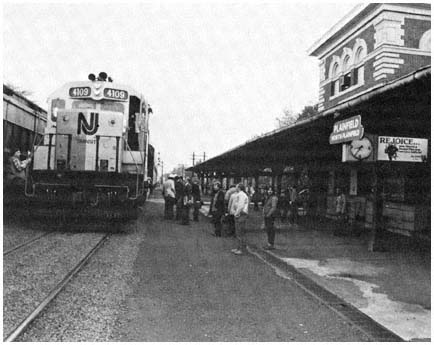

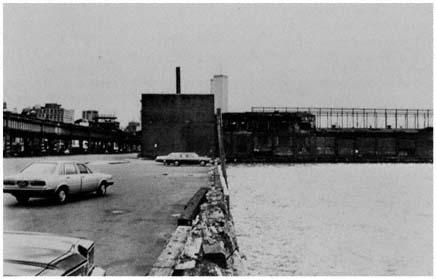

A commuter train operated by the state of New Jersey

picks up passengers at the old Plainfield station on the

former line of the Central Railroad of New Jersey.

Credit: Barbara Reilly, Staff Photographer, New Jersey Transit

weary commuters stranded. The new cars needed to alleviate the crush were not expected to arrive until 1984.[104]

Finally, the program of new construction—the centerpiece of the 1968 plan—had been largely suspended since the early 1970s, a victim of rising costs and inadequate resources. A few segments of the 63rd Street line to Queens, and of the Southeast Queens line, were completed and a few others were under construction a decade later, though they were far behind the original time schedule. Only a small part of the fabled Second Avenue subway had been started, and other projects, such as the new rail line connecting Kennedy Airport with Manhattan and the East Side transportation center in Manhattan, had never moved off the drawing boards. Nor were there prospects for going ahead with most of these projects in the near future. In 1968, the estimated costs for the new transit lines were $1.3 billion; by 1973, the total had risen to more than 2.5 billion. At that point the MTA stopped estimating the cost. In the winter of 1978–1979 the alert pedestrian could still see signs on Fifth Avenue near 63rd Street in Manhattan, proclaiming "the MTA's overall program of adding over 40 miles of new subways," but these

[104] The commuter's fate is aptly described in David A. Andelman, "Rail Commuters Angry but Resigned," New York Times, January 24, 1980.

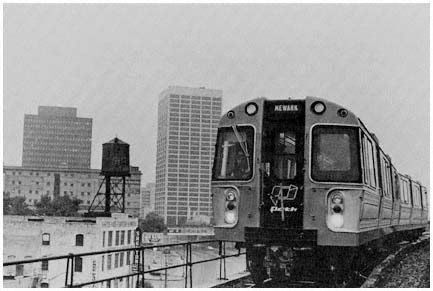

A new PATH train in Newark, from which the

Port Authority's commuter line provides service to

Jersey City, Hoboken, mid-Manhattan, and the World Trade

Center in lower Manhattan.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

were only monuments to past hopes now beyond the authority's means or realistic intention.[105]

The Port Authority in Disarray

On the west side of the Hudson a similar pattern of public action emerged, although the institutional development was quite different. Under the leadership of the state Department of Transportation (which succeeded the Highway Department in 1966), service was stabilized on most New Jersey rail lines, new cars were acquired for many of the routes, and a series

[105] The 1968 plan had called for more than fifty miles of new subway lines; by 1974 this had been cut to a promise of forty miles; and in 1978 the total had been whittled down to the Queens lines, totaling less than fifteen miles, with the hope that these segments would be open for service by 1985. Yet the MTA leadership, finding its construction plans delayed, pressed forward with rhetoric. Enticed by the same optimism and edifice complex that had captured the MRTC in the 1950s and their own predecessors in the 1960s, MTA's leaders in 1977 saw a "new awareness . . . spreading throughout the land about the problems and importance of public transportation," and felt "confident that this awareness will inspire a new resurgence of public transportation ridership." The authority therefore set forth a new 10-year $5.5 billion program to expand subway and commuter rail lines, earning the MTA a vigorous attack from New York City's planning commission, which argued that air conditioning of cars and other modest improvements would be a better use of scarce dollars than a costly building program. See MTA, Annual Report—1976, pp. 2–3; New York City Planning Commission, Capital Needs and Priorities for the City of New York (New York: March 1, 1978), pp. 23–27. See also the series of four articles by Grace Lichtenstein, "The Subways," New York Times, May 8–11, 1978, and Ross Sandler and David Schoenbrod, "Tunnel Vision, Too," New York Times, April 14, 1978.

of modest improvements in the system was initiated. State operating subsidies and funds for capital improvements were extended to bus lines, thus preserving commuter services which in New Jersey carried considerably more passengers than the rail lines. The costs of these subsidies to private bus companies grew rapidly, however, leading the state in 1979 to initiate action to take over ownership and operation of major bus lines.[106] Under the Port Authority, the Hudson Tubes became the PATH rail lines (for Port Authority Trans-Hudson) and were overhauled with new equipment and terminal facilities in lower Manhattan and Jersey City. As in New York, stabilization, overhaul, and increasing labor and other costs brought higher fares and continued dissatisfaction from New Jersey commuters. The new era also produced a series of ambitious plans for major improvements which were delayed by rising costs, conflicts over priorities, and disagreements over financing and institutional arrangements.[107]

The most serious dispute in New Jersey centered on the role of the Port Authority in mass transportation. As the 1960s drew to a close, the bistate agency seemed protected from further involvement in rail transit by the 1962 bond covenant, which effectively limited the Port Authority's rail transportation role to the PATH tubes. Friends and enemies alike viewed the covenant, which seemed to foreclose deeper authority involvement in rail transit, as a premier example of the strategic skill of its officials in defending the agency's independence and power.[108] What Austin Tobin had not expected was a governor who would demand that the covenant be changed and, when faced with resistance because of alleged constitutional barriers, would again demand that the covenant be changed—and further, insist that Port Authority officials agree with his view and make plans to plunge the agency deeply into rail transit, despite personal and legal reservations. But William Cahill, who was elected New Jersey's chief executive in November 1969, was such a governor.

Acting on his campaign promises, Cahill urged the Port Authority to press ahead with rail transit commitments and brushed off the protests of Tobin and his commissioners. By 1971, Cahill was using his veto power to delay its other programs, while advocating Port Authority action on a series of rail projects.[109] When Tobin defended the authority's position as a self-

[106] New Jersey's program and results are summarized in the annual reports of the state's Department of Transportation (NJDOT). On New Jersey's bus programs, see Bus Subsidy Program Study Commission, State of New Jersey, Report to the Legislature (Trenton: January 9, 1978).

[107] For a sampling of New Jersey's hopes, plans, and disappointments, see Peter Carter, "$300 Million Rail Plan Is Proposed by Hughes," Newark Evening News, May 16, 1966; NJDOT, A Master Plan for Transportation (Trenton: March 1968); Dick Gale, "$2.5-Billion 'Master Plan' Outlined For Rails and Highways," Trenton Evening Times, March 12, 1968; Richard Phalon, "Mass Transit a Key Issue in Jersey Governor Race," New York Times, May 29, 1973; and James Manion, "N.J. May Bench Conrail, Run Rail Lines Itself," Trenton Evening Times, August 31, 1978. In New Jersey, as in New York State, a crucial element in the delays and lost aspirations was the defeat of several transportation bond issues at the polls during the 1970s.

[108] On the negotiations leading to the creation of PATH, the World Trade Center, and the 1962 bond covenant, see note 48 above and associated text. The role of tax-exempt revenue bonds in maintaining the independence of public authorities is described in Chapter Six; see note 21 in that chapter and associated text.

[109] The Cahill projects included expansion of the PATH rail system to other areas of New Jersey, Port Authority purchase of the Penn Central railroad station in Newark, and construction of a new rail tunnel from New Jersey to Manhattan near 48th Street to provide "direct rail access tomid-Manhattan for all New Jersey commuters." Early in his second year in office, Cahill said he would take "a much more aggressive, determined and stubborn approach to the failure of the Port Authority," and he referred to the 1962 bond covenant as a Port Authority "device to permit it to escape additional responsibilities," which had been accepted, "incredibly," by the state legislatures. These criticisms, together with the governor's comments on new rail projects, are set forth in William T. Cahill, "Remarks at Chamber of Commerce Dinner," February 4, 1971.

supporting body and expressed doubt that it could assume large deficits and survive, Cahill attacked the executive director publicly. He also directed that the New Jersey commissioners caucus separately before board meetings to establish a "New Jersey point of view," and he warned them to follow his lead on the mass transit issue if they wanted to be reappointed.[110]

The Cahill barrage had an impact. In December 1971, Austin Tobin abruptly announced his retirement after nearly 30 years as executive director.[111] Five months later, the authority's vice-chairman, a respected banker who shared Tobin's views on the bond covenant, also resigned.[112] In the spring of 1972, after years of working with Tobin and his staff, Governor Rockefeller attacked the old regime and urged that William Ronan be chosen to replace Tobin and change the agency "from a rubber to a rails orientation."[113] That November the two governors announced that the Port Authority had agreed to a plan which, within the constraints of the bond covenant, would permit it to apply more than $250 million of its own funds to extend the PATH rail lines into the New Jersey suburbs, provide rail service between Manhattan and Kennedy airport, and carry out other rail projects.[114]

Then, in the spring of 1973, both states passed legislation ending the bond covenant for Port Authority bonds sold in the future, and a year later

[110] At a legislative hearing in early 1971, for example, Tobin protested: "Don't tell us that we can operate a mass transit system with a $300 million a year deficit on a self-supporting basis, . . . we can't, and God can't." In response to this typical Tobin strategy—emphasizing the extreme in rail transit burdens—Cahill exclaimed that Tobin "will not be making the decisions on what the Authority can or cannot do." See New York State Assembly Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions, and Autonomous Authorities Study Commission of the New Jersey State Legislature, Public Hearing (New York: March 5, 1971), pp. 92–93; Henry Lee, "Ronan to Be Named Port Authority Head," New York Daily News, March 15, 1972. On the separate caucus, see Alex Michelini, "PA Commish Defends the N.J. Caucus," New York Sunday News, April 2, 1972.

[111] Tobin announced his decision on December 12 and immediately turned over his duties to his long-time deputy, Matthias E. Lukens, who was designated acting executive director.

[112] The commissioner, Hoyt Ammidon, had previously defended Tobin's actions and publicly opposed proposals that might violate the 1962 covenant. Ammidon was also chairman of the board of the United States Trust Company, an investment company which would later bring suit on behalf of the Port Authority's bondholders to protect the bond covenant; see discussion below. His views are set forth in Hoyt Ammidon, "Port Authority," letter to the editor, New York Times, March 24, 1971.

[113] "We don't want a continuation of the Tobin structure," Rockefeller opined, "which as everyone knows was a very tight, highly political structure and opposed to mass transit." Rockefeller's attack was motivated in part by his sense that leadership in the mass transit area had been usurped by his fellow Republican from New Jersey. See Frank Mazza, "Rocky Raps PA Steamroller," New York Daily News, April 28, 1972, and the transcript of his interview with John Hamilton, WNEW-TV, April 9, 1972.

[114] The new program is described in Port Authority, 1972 Annual Report (New York: March 1973), pp. 6–8. Also in 1972, in response to Cahill's urging that the title of the "misnamed Port of New York Authority" be altered, the agency became "The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey."

both states overturned the covenant retroactively. With that hurdle allegedly out of the way, Port Authority tolls were raised sharply in order to provide more funds to carry out additional mass transportation projects. Ultimately, the scheme failed. The repeal of the covenant predictably brought a bondholders' suit, and in 1977 the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the states' action as a violation of the obligations of the contract clause of the Constitution.[115] The rail transit projects announced with fanfare in the early 1970s would have to be financed in some other way, not with Port Authority funds.

But the long battle to increase the authority's activities in mass transit had other results. In the complex world of the Port Authority, a sense of institutional purpose, effective central leadership, and staff morale had been crucially linked for thirty years to Austin Tobin's energy and intensive involvement in all major areas—and to staff expectations that funds would be available to permit them to carry out ambitious programs. As Tobin's energies became absorbed in the battle with Governor Cahill, the potentially separate empires—airports, world trade, and the other departments—began to drift apart; and when that conflict cast into doubt the ability of the Port Authority to raise and employ the sums needed to achieve large purposes, staff members worked less for the institution and more for themselves. The process was subtle: some did not know it was happening. And the change in the institution was uneven: in some areas, where there were new plans afoot, a lively interest in the future remained. But in department after department, a sense of forward motion—of the possibilities for forward motion—crept out, and staff morale fell.

Had Tobin II replaced Tobin I, it might have been different. But in December 1971 Tobin's replacement was a career staff member, designated as "acting" executive director; and he in turn was succeeded in 1973 by another careerist with the same tentative hold on the office until receiving a regular appointment in the fall of 1974.[116] Perhaps neither of them had a taste for vigorous leadership; but in view of the uncertain legal situation and recurrent gubernatorial forays, it would have required a person of quite unusual abilities to do much better. Had Rockefeller's first choice been accepted in 1972, power might again have flowed into the staff director's office; but William Ronan was not acceptable to a majority of the commissioners, because of his advocacy of deeper rail transit involvement and their

[115] Immediately after the repealer was signed in New Jersey, the United States Trust Company filed a suit against the state. In 1975–1976, the trial court and the New Jersey Supreme Court found the statutory repeal to be a reasonable exercise of the state's police power, not prohibited by the state or United States constitutions. On appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision, concluding that the repeal, by permitting Port Authority funds to be used without restriction to fund rail transit projects (which might generate large deficits), had substantially impaired the bondholders' security, and therefore had violated the contract clause of the U.S. Constitution. See John H. Allan, "Law Dismays Municipal-Bond Dealers," New York Times, May 1, 1974; Roger Harris, "P.A. At the Crossroads," Newark Sunday Star-Ledger, August 21, 1977; United States Trust Company v. State of New Jersey, 431 U.S. 1 (1977).

[116] Matthias Lukens served in an acting capacity from the time of Tobin's exodus until he retired in August 1973; his successor, A. Gerdes Kuhbach, was acting staff director until August 1974, when he was named executive director. Lukens had been with the Port Authority for 24 years prior to replacing Tobin, including eleven years as Tobin's deputy. Kuhbach had been with the New Haven Railroad until 1962, when he joined the authority as director of finance, the position he held until replacing Lukens.

fear that this effort would end the vitality of the agency as a self-supporting enterprise.[117]

For a time the leadership vacuum was filled by Ronan, who had served on the board since 1967 and became chairman in May 1974. But his strong protransit stance and earlier criticisms of other Port Authority officials made it difficult for him to gain support within the agency. For example, in 1972 he criticized his fellow commissioners publicly for appearing to "assign a higher priority to the bond market than to mass transportation" and expressed doubt that the board majority was "highly motivated toward the difficult decisions necessary" to fund large transit projects.[118] By the end of 1974, Ronan himself had been publicly rebuked by Brendan Byrne, Cahill's successor as governor, for failing to make progress in mass transportation, and he was criticized inside the agency for his unwillingness to let staff members make decisions, while being largely absent from the Port Authority offices himself. As one commissioner noted openly in November 1974, "nothing is getting done." The authority was "dead in the water."[119]

So the Port Authority drifted. Bridge and tunnel tolls were increased in early 1975 to fund mass transportation projects, an expansion of the Manhattan bus terminal was begun later that year, and in the spring of 1976 the governors of both states again announced that the Port Authority would help to finance a new mass transit program. But the 1972 program had never gotten underway, the legal uncertainties remained, and the authority's financial position had weakened—mainly due to multimillion-dollar yearly deficits generated at the World Trade Center, PATH, and Newark Airport.[120]

In the spring of 1977, frustrated by the agency's inability to devise a legally acceptable transit program, Governor Byrne began vetoing board actions on all subjects, further undermining morale and a sense of direction at the authority. Byrne demanded that the agency either find a way to use the added moneys for mass transit, or rescind the 1975 toll increase. Otherwise,

[117] Ronan was known to be strongly interested in the post, He had already built a strong national reputation at the MTA, and the Port Authority, with its large net income base, would offer greater opportunities. Several factors undermined Ronan's candidacy: his sometimes arrogant style lost him support; his active effort in 1971 (as MTA chairman) to oppose federal funds for a Port Authority rail project—he argued that the MTA needed the money more—counted against him; and Governor Cahill was wary of Ronan's fondness for New York State and for Rockefeller, whose influence might tilt authority policies against Cahill's already beleaguered state. The evolution of the conflict is described in the following articles: Frank J. Prial, "Port Agency Seeks Successor To Tobin Within the Authority," New York Times, March 16, 1972; Frank J. Prial, "Port Authority Dissent: Ronan Gives a Hint of the Bitterness and Strife Among the Commissioners," New York Times, April 1, 1972; and Edward C. Burks, "Ferment in Mass-Transit Agencies," New York Times, April 5, 1974.

[118] See "Ronan Letter to Port Unit," New York Times, March 31, 1972. On various occasions, he had also criticized Tobin and other agency staff members for failing to meet their mass transit responsibilities.

[119] The quotations in the text are taken from Frank J. Prial, "Port Authority Has Fallen on Hard Times," New York Times, November 10, 1974; Prial's article accurately describes the authority's malaise during the mid-1970s.

[120] The Trade Center deficit reached $7.9 million in 1974 and $11.9 million in 1975; and a $400-million expansion program at Newark Airport added several million more ($8.6 million in 1975). In 1975 the PATH deficit exceeded $37 million. Between 1973 and 1977 total Port Authority personnel shrank from more than 8,000 to less than 7,700. The Port Authority deficit figures are set forth in the report of the New York State Comptroller, "Public Authority Financial Analysis Statements, No. 8–76" (New York: November 1976).

he said, "I will not let them operate. I will veto the minutes." While authority commissioners and staff searched feverishly for a way to underwrite mass transit without violating the bondholders' rights, Byrne vetoed the minutes of the board in May and again in June, thus blocking the Port Authority from approving contracts and taking policy actions in a wide variety of areas. Continuing to apply pressure during the summer, Byrne criticized the authority as "too staff-dominated" and as populated by people who take a negative view of rail transit. While denying that his widely publicized efforts were motivated by a desire for votes in his 1977 reelection campaign, the governor acknowledged that his constituents would welcome either forward action on a transit plan or a toll reduction.[121]

Then, for the first time, scandal touched the agency's top officials. Rumors of inflated and fraudulent expense vouchers, of authority cars and helicopters appropriated for family outings of senior staff and commissioners, and of contract irregularities reached the press. By the fall of 1977 three senior officials had been disciplined, one had committed suicide, and New York State's Comptroller's Office had issued several detailed reports describing "extravagancy at public expense," "widespread padding of expense accounts," and other examples of misuse of public funds and of managerial weakness.[122]