Preparation of Skins

Tanned skins were useful for daily wear, and they supplemented cotton cloth, which, because of the time and labor required for its fabrication, could not have been produced in sufficient quantities. In the earliest Spanish records a follower of Coronado says of Zuñi: "The clothing of the Indians is of deerskin, very carefully tanned, and they also prepare some tanned cowhides [buffalo] with which they cover themselves, which are like shawls, and a great protection."[25]

The skins of wild animals are tanned and cured to make various garments and articles of ceremonial paraphernalia among the Pueblos. The material culture and the development of certain peoples are greatly influenced by the animals found in their districts. "The flesh ... furnishes food, the skins provide raiment, thongs and other useful products, and bones furnish awls and other implements; but perhaps even more important from the cultural point of view, is the fact that animals enter largely into the mythology and religion."[26]

We find not only the names of clans and individuals emerging from this association, but special parts of animals becoming symbolic in religious observances, such as the use of bears' paws in the rite of curing and the use of the headdress of the buffalo skin and horns in the Animal Dance. Animal horns were used on other headdresses and masks. Rattles were made of bones and hoofs. Horsehair, goat and bear skins, and wool were sometimes dyed and used as beards, wigs, and ceremonial trimmings.

* The rabbitskin blankets were always woven by the women.

Even the six directions bore the symbols of various animals. Thus the mountain lion represented the north; the bear, the west; the badger, the south; the wolf, the east; the shrew, the nadir; and the zenith was represented by the eagle.

Furthermore, special qualities in certain leathers have produced a type of ceremonial apparel which could not have been realized had any other medium been employed. Helmet masks are fashioned from the heavy neckpieces of deerskin, buffalo hide, or present-day cowhide, while softtanned deerskin is made into kilts and mantles.

The variety of animals living on the arid plateaus of the Southwest was limited. The most familiar were probably antelope, coyote, and rabbit. Many legends center around the coyote, whose skin, it was believed, often concealed the metamorphosed body of some immortal creature. Rabbits were easily killed, and, since they were a prerequisite of the feast following the period of fasting and denial, they were hunted by large ceremonial groups, who encircled an allotted area, closed in on their prey and killed them with a throwing stick, a kind of boomerang which though curved did not return to its thrower.

Deer must have been plentiful, particularly in the winter when heavy snows in their high shelters forced them into the valleys in search of food.

Their beasts of prey were the bear, wildcat, mountain lion,[27] and fox. Of these the bear and the mountain lion were thought to be human beings who put on these skins at pleasure.[28] Great-horned mountain sheep were found in the high country on the south as well as in the Rocky Mountains on the north.[29] Likewise we are told of skunk,[30] squirrel,[31] porcupine, raccoon, badger, and otter. The former governor of Santa Clara wore summer ermine wrapped around his two braids when I called upon him at his home in the summer of 1936.

Through trade with other peoples the Pueblos were able to increase the quantity and variety of the skins which they used for their ceremonial and dress occasions.

Their neighbors to the east were Plains tribes whose existence centered in the herds of bison which roamed the prairie because it was mainly from these that they fed and clothed themselves. The need of a more varied diet sent these braves, who on other occasions were warlike, to barter their beautifully tanned leathers and pelts, preserved skulls, and bone beads for the delicious corn meal so painstakingly ground by the Pueblo women.[32] On the west, other seminomadic groups exchanged hides and pelts for the finely woven blankets, robes, and kilts of Hopi manufacture.[33]

As the Pueblos were a village people primarily concerned with agriculture, they depended for their food and clothing upon such crops as they could raise. They hunted only occasionally, in order to obtain skins for ceremonial needs and to procure the small amount of meat they needed to strengthen their vegetable diet. The hunt was a requirement prescribed by the War fraternity and directed by the warrior priests. To the Pueblo people all animals are living spirits and their right to exist is unquestioned. It is necessary, therefore, to pray to the animal and its family that it allow itself to be used for food and ceremony. After the kill, more rites must be observed, so that the spirit may not be displeased but may return to the other world and tell its kindred of the fine treatment accorded it.

The people of Taos and Picuris were descended from a Pueblo group who were tainted with the hunter's blood of the Apache and the Comanche. Living in close proximity to the plains, they had intermarried with the Plains Indians and had acquired habits resembling those of the aggressive, warlike marauders. They made long pilgrimages into the prairie country in search of bison.

Because they lived in the midst of wooded mountains, great herds of deer and elk came to the edge of their villages. It is not strange, therefore, that we find them much more influenced by their Plains brothers and eager to acquire the deerskin shirt and leggings, while their wives and daughters, Pueblo in their daily lives, sought to borrow the fringed

dresses for their festival occasions. Here, then, we find a fusion of two cultures in dress and in society and ceremony. In contrast, along the Rio Grande, at Zuñi, and among the Hopi were people, peaceful by nature, who bartered their corn and turquoises for skins which they made up after their own traditional patterns.

Since the surrounding tribes clothed themselves in skins and their methods of tanning were practically the same, the Pueblo men undoubtedly knew the technique of skin dressing and employed it in much the same manner as their neighbors.

Certain steps had to be followed in skinning an animal. There must be no waste. All the hide was retained. Sometimes the paws and hoofs were kept intact. This principle can be observed in the pendent foxskins worn at Zuñi or the head preserved on the fawnskin bag worn over the shoulder of the Zuñi fire god.[34]

A concise description of the manner in which skins were dressed by the Plains Indians is given by Frederic Douglas: "First the wet hide was staked out on the ground, hair side down, and the flesh, fat, coagulated blood, and fragments of tissue scraped off with a toothed gouge or fleshing tool of bone or iron. Second, the hair was removed and the skin reduced to a uniform thickness by scraping, each side being worked over in turn with an adze-like tool."[35]

The immersion for a few days in a lye bath of ashes and water to aid in the removal of the hair[36] is suggested by Catlin.

"If rawhide was desired, nothing further was done to the hide. If soft flexible skin was needed, a third step was taken. A mixture of brains and any one or several of the following materials, cooked ground-up liver, fats and greases of various kinds, meat broth and various vegetable products, was thoroughly rubbed into the hide. When well saturated with this compound, it was allowed to dry, then soaked in warm water and

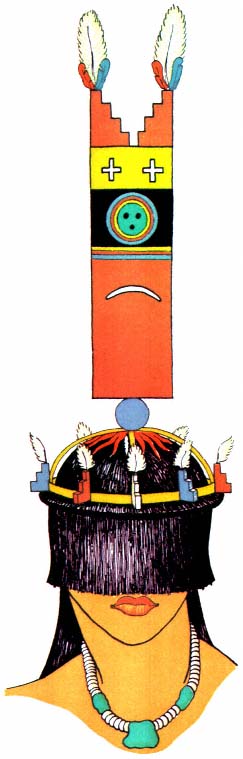

Plate 10.

Tablet headdress worn by the Zuñi Corn Maidens. The

natural hair shields the face. (After Stevenson, 1904, pl. 37.)

rolled up into a tight bundle. The final step was the stretching of the hide as the braining process caused great shrinkage. The hide was alternately soaked in warm water and pulled with hands and feet, pulled down over a rounded post, or stretched by two persons if the hide was large. Friction caused by rapidly pulling through a small opening was also resorted to to give greater softness. The dressing process was complete when the hide was nearly its original size and thoroughly softened and smoothed."[37]

Catlin describes a further step, that of smoking, which, he says, makes it possible for the skins, "after being ever so many times wet, to dry soft and pliant as they were before."[38]

It is true that the Indian dressed skin can be wet again and again and it will always dry with its original flexibility. This fact is made use of in the making of any special leather articles, such as moccasins and masks. The moccasin is cut to the pattern of the foot it is to cover, sewn, and packed in wet sand until saturated. The owner then allows it to dry on his foot, and shrinkage makes it fit perfectly.

The Havasupai, a group of seminomadic Indians who live in summer near their cornfields in Cataract Canyon—a deep chasm cutting into the south side of the Grand Canyon about a hundred miles west of the Hopi,—are also skillful tanners. They use a "process of rubbing beef brains and marrow and yucca pulp into the hides with the hands."[39] Many raw deer hides come to them from the Colorado River tribes farther to the west. These they tan and use in trade with the Hopi.

Among the Pueblos the tanning was done by the men; among the Plains tribes, by the women.

Pelts were cured in the same manner, but the hair was left on. The pelts, like the dressed skins, are impervious to water. A trader at Zuñi told me that the foxskin tailpieces (pl. 24) used in ceremonial dances were buried in damp sand for several days before being worn. They appeared, when brought out for wear, soft, sleek, and glossy.