2. Idumea and Samaria

The same conclusion appears from the passage referring to Idumea and Samaria (para. 107). Bickerman, in one of his inspiring articles, drew attention to this passage long ago and used it as evidence for dating the book between the years 145 and 127.[23] He based his analysis on the traditional assumption that Idumea and central Samaria were conquered by John Hyrcanus around the year 128. The recent excavations in Marisa and Mount Gerizim have, however, definitely proved that Idumea and southern Samaria were occupied only in 112/11 or shortly thereafter.[24] In addition, the chronological implications of the passage on the Jerusalem citadel escaped his notice. A modification of Bicker-man's chronological analysis of the references to Idumea and Samaria and his arguments is therefore required (cf. Maps 3, 5, PP. 118, 126 above).

Pseudo-Aristeas tries to explain why Jerusalem is not a large city.[25] Following the autarkian ideal, he says that the founders were aware of the advantages of a proper dispersion of the population in the rural, agricultural lands, so as to provide the city with adequate supplies. In this context he describes the terrain and agricultural possibilities of the lands belonging to the city (para. 107):

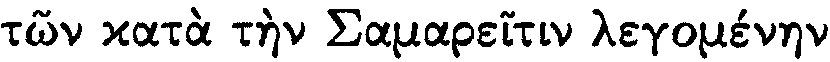

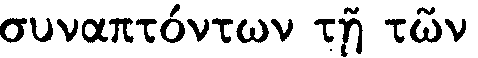

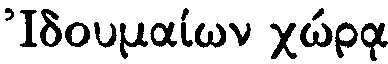

For the country is large and good, and some [of its parts], those in the so-called Samareitis [

][26] and those adjacent to the country of the Idumeans [], are flat. But other [parts] are mountainous, those (in the center of the country. With regard to them it is necessary)[27]

[23] Bickerman (1930) 280ff. See also nn. 33 and 55 below.

[24] See p. 131 nn. 28, 29 above.

[25] For his motive, the inevitable comparison with Alexandria, see p. 110 above.

to attend constantly to agriculture and soil, so that in this way they will also bear much fruit.

The author thus calls the Hebron Hills "the country of the Idumeans." In the time of the First Temple the region belonged without interruption to the Judean kingdom and was inhabited by the tribe of Judah. After the evacuation of the Jewish population with the destruction of the Temple, the region was settled by Idumeans. Consequently it was named Idumea from at least the beginning of the Hellenistic period.[28] In 112/11 it was occupied by John Hyrcanus; its inhabitants were converted to Judaism, and the region was integrated into Judea.[29] The official name of the Hebron region under the Hasmoneans is anybody's guess.[30]

Whatever its name after the occupation was, the author uses the phrase "the country of the Idumeans," which is much more expressive than just "Idumea." A Jewish author living in Alexandria would not have used this phrase in the generation immediately after the

[28] See M. Stern (1968) 226, and esp. Diod. XIX.95, 98, drawing on Hieronymus of Cardia.

[29] Ant . XIII.257; on the date, see p. 131 n. 28 above.

[30] The only piece of information directly relevant to the Hasmonean kingdom is to be found in Ant . XIV.10. However, that statement, which refers to Herod's grandfather, was taken from Nicolaus of Damascus (cf. Ant . XIV.9, >Bell . I.123-24), Herod's court historian. He may well have used terminology from the time of his Idumean Maecenas, when the region naturally acquired a special status. On this status, see M. Stern (1968) 226.

annexation and forced Judaization of the region by John Hyrcanus,[31] when there must still have been considerable sensitivity about the Judaization of the region.[32] An explicit admission that the region was "the country of the Idumeans" would also have caused considerable embarrassment to Egyptian Jews in their confrontations with the Idumean settlers in Egypt.[33] These confrontations produced, some generations earlier, the Idumean version of the notorious ass libel, which was based on, among other things, the ethnographical-religious division between Judea and the Hebron region.[34] Furthermore, if the accepted restoration of the lacuna in the sentence about the mountainous regions is correct (which it almost certainly is),[35] then only the mountainous regions "in the center"—that is, between Jerusalem and the plains "adjacent to the country of the Idumeans" on one side and the plains of "the so-called

[31] On the forced character of the Judaization of the Idumeans, see the recent sensible comment of Shatzman (1990) 58 n. 90; Feldman (1993) 325-26 (pace Kasher [1986] 46-77, 79-85). On the reference in Strabo XVI.2.34, see my note in Anti-Semitism and Idealization of Judaism , chap. VI.6. It is well in line with Posidonius's idealized and fictitious conception of the origo of the Jewish people (Strabo XVI.2.35-36), which was by itself inspired by his political and religious ideals.

[32] Josephus does indeed refer many times to the converted Idumeans as "the Idumeans" in his account of the Great Revolt against the Romans, and at least half the former Idumean territory still preserved the old name, being a toparchy of Judea proper in the time of the Revolt (Bell . III.55; and see M. Stern [1968] 226-29 on the toparchies of Idumea and Engeddi). But the Judaization of the area was by then already an established fact; the Idumeans had proved their loyalty and even extreme zealousness during the Revolt, and there was thus no reason to disguise their ethnic origin. Moreover, it seems quite clear that Josephus wanted to stress their non-Jewish descent and thereby explain their ruthlessness and immoral behavior (e.g., Bell . IV. 232, 310).

[33] Bickerman (1930) 280ff. argued that the expression "land of the Idumeans" proves that the book was written before the occupation of Idumea. In a later version of the article ([1976-80] I.131 n. 93) he changed his mind and noted that the reference has no political but rather a purely geographical connotation, and refrained from using it as evidence for his dating (following Tcherikover [1961a] 317 n.8). Regrettably, he was not aware of the propagandist significance of geographical and administrative designations in the newly independent and expanding Jewish state. A similar policy can be observed in modern Israel, especially after the 1967 war ("Judea and Samaria").

[34] Ap . II.112. On the origin of the story among the Idumean settlers in Egypt, see M. Stern (2974-84) I.98.

[35] See n. 27 above.

Samareitis" on the other—are referred to. The Hebron region is thus not counted among the sources of supply for Jerusalem, which means that it did not belong to the Jews. All in all, the passage could not have been written after 112/11, when the region passed into Jewish hands and was integrated into Hasmonean Judea.

Less significant is the exact geographical meaning of the reference to flatlands "adjacent to the country of the Idumeans." These lands may be the valleys of the southern Shephela, the hilly region west of the central mountain range (like the Elah Valley and several smaller ones), adjacent to the Idumean territory. However, it would have taken considerable expertise to be so accurate, and even had the author gone on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem (which is still doubtful),[36] this would not have been enough: after all, not too many modern Israelis have a precise knowledge of the topographical features of the fringe areas of the Judean Hills. It may well have been an "armchair deduction" from the account in I Maccabees of the flight of the Seleucid troops after the battle of Ammaus, on the fringe of the Judean Hills: the Seleucid troops, who camped "near Ammaus, in the land of the plain" (3.40), are said to have fled after the battle to the "plain" (4.14), and then to have been pursued up to the "plains of Idumea, Ashdod, and Jabneh" (4.15). Pseudo-Aristeas evidently utilized and interpreted for his own purposes certain other minor details found in I Maccabees.[37]

The reference to Samaria is a bit more complicated. Part of the fertile flatlands belonging to the Jews is said to be in "the so-called Samareitis." The chronological conclusion from the reference to the "country of the Idumeans" does not allow us to interpret the sentence as referring to the situation after 112/11, when southern Samaria was occupied by John Hyrcanus—and certainly not after the conquest of northern Samaria and the Great Valley in the year 107. The possibility of identifying these plains with the internal valleys of central Samaria or the Jezreel Valley has therefore to be discounted. Bickerman's suggestion that the author had in mind the three toparchies in southern Samaria (Aphairema, Lydda, Ramathaim), attached to Judea in 145 (I Macc. 10.30, 38; 11.34), remains the only possible solution. Bickerman has also pointed out that Lod, one of the toparchies, is indeed flat.[38] As a matter of fact, one would

[36] See pp. 272, 275.

[37] See p. 278 and n. 21 above. Cf. next paragraph.

[38] Bickerman (1976-80) I.130-31.

not expect the author to have known this. He may well have believed, on the basis of their mention in two royal documents in I Maccabees, that all three toparchies were (or had) fertile plains. The attachment of the three Samaritan toparchies to Judea by the Seleucid kings is listed in two documents among many other economic concessions and grants (I Macc. 10.38, 11.34), a fact that by itself could have led to the conclusion that they were especially fertile. Moreover, the second document even declares remission of taxes on the "produce of the soil and fruit trees" for the annexed toparchies alone (11.34).[39] As "produce of the soil" in this context is certainly wheat, Pseudo-Aristeas could have deduced that the three toparchies were flat. His thorough reading of the documents need not surprise us, given that he could reshape and integrate a single piece of information from the first document (10.36), elsewhere in the course of his narrative (para. 13).[40]

The passage indicates that the three toparchies were still popularly named "the Samarias" or the like: hence, probably, the expression "in the so-called Samareitis,"[41] and not just "in Samareitis." The phenomenon of the preservation in colloquial usage of a former administrative designation or place name some generations after an official change has taken place is well known in the geographical history of the Holy Land. This was often done out of habit or was meant to call attention to the history of a region or locality. In contrast to what was said above about "the country of the Idumeans," there need not have been any ideological or practical reservation against applying the name "Samaria" in this case: it was, after all, one of the two traditional biblical names of the region (the other being Mount Ephraim), and the area of the three toparchies traditionally belonged to the northern Israelite kingdom and the northern tribes.

It is worth stressing that the absence of any reference to agricultural lands belonging to the Jews on the coastal plain does not necessitate a dating before the occupations of Jaffa and the corridor to the sea by Simeon and several of the coastal cities by John Hyrcanus.[42] The

[39] In the first document (I Macc. 10.30), the concession refers to the whole territory of Judea, together with the three toparchies.

[40] See p. 278 and n. 21 above.

[41] On the ending -itis for Samaria, cf. Pseudo-Hecataeus ap . Jos. Ap . II.43; and see p. 114 n. 189 above.

[42] For the date of these occupations, see pp. 124-27 above and 292 below.

author does not refer to the Jericho Valley either, which had been included in the boundaries of Judea since the Restoration.[43] This flat land on the eastern side of the Judean Hills was considerably larger than the "corridor," and its fertility and unique flora were celebrated by Hellenistic historians and geographers.[44] It thus appears that for one reason or another connected with the special context and purpose of the account,[45] the author restricted himself to the mountain range (and its internal valleys).