PART SEVEN—

GROUP TEXTS

The films made by Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, Bruce Baillie, Stan Brakhage, and many others—what do we call them? Underground cinema? That term refers both to midnight showings at feature film theaters and to literally fugitive showings in the days of censorship, when a hostile society sent police to enforce its disapproval. Experimental cinema? This suggests a process of trial and error that never does resolve itself aesthetically. Independent cinema? Independent these filmmakers certainly were, but the term must be shared with many postwar documentaries and with feature films of the low-budget variety. Indeed, four of the five feature films nominated for an Academy Award in 1997 were "independently produced." Avant-garde is probably the best term, if only because it is the one most used by filmmakers and critics in this area. Whatever the name of this cinema, it is doing well: new avant-garde filmmakers emerge every year, and several of the pioneers have been honored. Among the first 100 films selected for permanent preservation in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress are Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), by Maya Deren; Dog Star Man (1964), by Stan Brakhage; and Castro Street (1966), by Bruce Baillie.

Unfortunately, there is not always an easy way to see even these well-known avant-garde films and such films, even when available for study, are notoriously difficult to write about. Even though all four of the films discussed in the Spring 1976 Special Feature were highly regarded, the essays by the three writers included here were an act of faith in the future. It is worth noting that Film Quarterly has been interested in avant-garde film for most of its forty years, a commitment that has remained constant at least since the early 1970s. In Spring 1971 Bruce Baillie appeared on the cover in a still from his film Quick Billy; and an image from Tom DeWitt's Fall appeared on the Spring 1972 cover, with an accompanying essay by John Fell. Later highlights include a dossier on Yoko Ono's film work in the Fall 1989 issue and numerous other essays and/or interviews by Scott MacDonald concerning Ernie Gehr, Andrew

Noren, Anne Severson, Yvonne Rainer, Martin Arnold, and others. There have also been interviews of Holly Fisher and Barbara Hammer, as well as attention to a number of figures poised in diverse ways between the avant-garde and the independent feature, including Peter Greenaway, Jan Lenica, Todd Haynes, Sally Potter, Maggie Greenwald, Gregg Araki, and Monika Treut.

Lucy Fischer's essay on Castro Street correctly calls the film "fundamentally an abstract composition." The anecdotal comments she quotes from the filmmaker tell us only where he gathered the images for his work, including some of the stunning shapes and colors of the final film:

Castro Street running by the Standard Oil Refinery in Richmond, California . . . switch engines on one side and refinery tanks, stacks, and buildings on the other—the street and the film ending at a red lumber company.

A series of oppositions define the film—a phase of movement of camera and/or objects moving right is countered with another moving in the opposite direction. Color and black-and-white images are continually opposed and/or superimposed in whole or part. "Clearly it is this sense of oppositions confronted and synthesized which one perceives as dynamic resolution" in viewing the film. An additional subtlety in the film is Baillie's blurring the distinction between the movement of the camera and the movement of its object. Is the train in a shot moving or is the camera moving across it?

To Parsifal (1963) is an early Baillie film—his fourth overall and his most serious work to that time. (Virtually all of Baillie's best work was completed between 1961 and 1971: twelve films in eleven years.) As Alan Williams points out, the sixteen-minute film is divided equally into two parts of eight minutes each:

Part one depicts a sunrise, a journey out to sea in a boat, then gulls flying around the boat while fish are cleaned, and finally the journey back and the reappearance of land. [The bright red blood of the fish stains the predominantly blue and white images of the film to that point.] In part two the setting changes from sea and coastline to a mountain forest traversed by railroad tracks. Workmen are seen repairing the tracks, after which a train passes through the forest while a nude woman stands nearby. The woman washes herself in a stream as insects move on ground and water. Then the workmen are seen repairing the tracks; a train appears and a man's hand pulls the woman away from the camera as the train continues through the forest, illuminated by a setting sun.

What we see of the woman is mainly limbs, hands, and feet; what is shocking, as nearly always in Baillie's work, is the contrast between colors: the tones of her skin and those of the forest. Thematically, the woman and forest, on the one hand, are opposed to the tracks, workers, and train, on the other. The conjunction of woman and nature is at once classical, ideological, and banal. The conjunction of man with thrusting technology is presented explicitly here as the rape of nature. The extensive use that Williams makes of Wagner's Parsifal —excerpts of which are played in both parts of the film—is most illuminating.

William R. Barr's four-page note concerns two Brakhage birth films, Window Water Baby Moving (1959) and Thigh Line Lyre Triangular (1961). The earlier film, included in many college campus collections, is seventeen minutes long; the second is five minutes. P. Adams Sitney classifies both as "lyrical films," but Barr plausibly insists that the first is half-lyric and half-documentary. Barr sees the second film, which uses extensive painting on the images, as "a layered, integrated affirmation of all creativity." He sees it also as an important step toward Brakhage's later work.

A refreshing aspect of Barr's piece is his willingness to criticize Brakhage for "the egocentricity of his commentary" on Window . It is clear from Jane Brakhage's testimony and from Stan's own accounts that she contributed importantly to the planning and execution of the film, which he is at pains to claim as his own alone. Barr's firmly expressed reservations go hand in hand with his affirmation of Brakhage's power and importance as an artist.

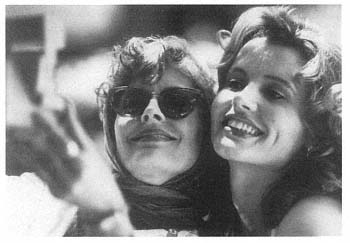

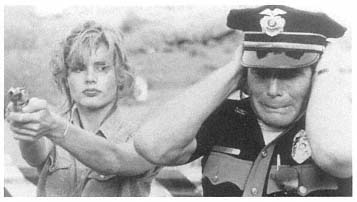

Had it been written twenty years ago, Thelma & Louise might well have ended up as a Roger Corman picture; it would have fit right in with Corman's own Bloody Mama (1969) and the Corman-produced Boxcar Bertha (1972) and Crazy Mama (1975), directed by Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme, respectively. In those tough, low-budget films there was no Ansel Adams lighting and no policeman who seems to be bucking for the Nobel Peace Prize. Also, needless to say, the women in those films committed and ran from actual crimes, not self-defense against a brutal attempted rape.

That was then, and it is precisely its relation to the now that makes Thelma & Louise so fascinating. It seems that most films these days are either hits or flops—the middle range has narrowed considerably. It took a big production, big stars, and a big director and cinematographer to make even such a well-crafted, nicely judged script into a successful film. Or, more precisely, to attract enough initial attention to reach Friday–Saturday moviegoers.

A number of our eight contributors devote attention to the question of genre in Thelma & Louise . Harvey R. Greenberg recalls Ridley Scott's earlier work as using "popular genre toward revisionist ends": The Duellists (1977), Alien

(1979), and Blade Runner (1982). But Thelma & Louise "arguably wins the prize for sheer number of genres interrogated against the grain in a single Scott picture." Greenberg identifies classic and contemporary Westerns, various subgenres of road movies, and seventies buddy movies. Leo Braudy suggests Westerns and film noir. Peter N. Chumo II sees the film as what he calls a "road screwball comedy," of which It Happened One Night is the prototype. Other outlaw films, even those with deadpan humor, nevertheless lack "the self-awareness or growth typical of the smart, witty screwball heroine." Screwball's "liberation and growth through role-playing" are seen, for instance, in Thelma's robbery of the market. The scene with the policeman and other scenes reveal the "smart, sassy lines of a screwball heroine who has a sense of humor about her situation." However, whereas the screwball couple "normally achieve a clarity of vision that enables them to be reintegrated into society," in Thelma & Louise this does not happen.

Brian Henderson's contribution deals with the narrative organization of Thelma & Louise . Although, like most films, it tells its story chronologically, it organizes narrative time, and the distinct temporalities that result, in a way that powerfully enhances its theme. The heroines are always shown together, with the exception of two scenes that create contrasts by crosscutting between them. The main body of the film is structured by crosscutting between the escaping protagonists and their reluctant pursuer, the FBI agent who is monitoring their case. Both the police scenes and the scenes with Thelma and Louise are temporarily indeterminate. This is a worry-free scheme that allows the filmmakers to elide what they wish in each story, but it also serves to immerse us in the divided temporality of the heroines: a continual motion forward and a continual reflection backward.

Linda Williams compares Thelma & Louise not only to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid , with which it shares a final, all-but-fatal freeze-frame, but also to "that most resonant of revenge Westerns, John Ford's The Searchers ." Like Ethan, Louise has a clouded past that is referred to vaguely and never explained. We suspect, from her angry, vengeful reaction to her friend's imminent rape, that rape was likely her trauma in Texas. She notes also:

The sheer surprise of Thelma & Louise is to have shown, in a way that serious films about the issue of rape (cf., The Accused ) could never show, how victims of sexual crime are unaccountably placed in the position of the guilty ones, positioned as fair game for further attack.

Carol J. Clover emphasizes not those men who disliked Thelma & Louise , as early debate about the film did, but the far more significant fact that large num-

bers of men saw it and liked it. Indeed, she believes that "a real corner in gender representation has been turned in mainstream film history." But the same corner was turned fifteen years ago in so-called exploitation cinema. Horror fans recognize the "tough-girl heroes" in various mainstream films as "upscale immigrants from slasher and rape-revenge movies of the eighties—forms that reveal in no uncertain terms the willingness, not to say desire, of the male viewer to feel not just at but through female figures on screen."

Albert Johnson's piece—"Bacchantes at Large"—and Leo Braudy's—"Satire into Myth"—are oddly parallel and complementary, not least in taking a large view of Thelma & Louise . Johnson calls the film "an entertaining and picaresque tragicomedy" and a vivid portrait of an America in which women are still struggling to define their individualities: "it is a symbolic perusal of feminine inconsistencies." He notes Louise's "totally realistic" version of the world, and her exasperation with Thelma's naivete becomes a bitter commentary on the failure of her own hope. He also notes an aspect of the film that has escaped notice. "Much attention is given to landscape; the imitation Hollywood motels off the highways; a conglomerate of oil wells in dusty twilights; and faces of aged, displaced people, seen briefly in doorways and windows, remnants of lost dreams (particularly for Louise, who notices them)."

In the country-western bar the characters visit, Leo Braudy observes, "men and women alike wear the paraphernalia of fantasy western individualism. In this atmosphere of the ersatz and the fallen," the attempted rape of Thelma and Louise's killing of the rapist "cuts through like an icy blast, announcing the violence and brutality under the celluloid-thin mists of self-sufficiency and heroism." On the road, the camera stresses the "choking inevitability of the world they are trying to escape," not just the massive machinery, the oil drills and trucks, but even Monument Valley: the benevolent spaces of John Ford Westerns are shot as walls constraining the heroines. As opposed to Scott films centering on "romantically posturing men," Thelma & Louise opts "more for wisecracks and the techniques of comic exaggeration than for self-important despair." The film's "violence erupts within a hard-edged satire of wannabe heroism and consumer identity" and builds to a conclusion that moves the duo "out of this heightened satiric reality into myth."

Marsha Kinder's piece is a fascinating comparative study of Thelma & Louise and Messidor (1979), a film by Swiss filmmaker Alain Tanner, whose works "address feminist concerns within a broad political context that also includes issues of class conflict, racism, and transnationalism." Both films are road movies about a pair of women who "abandon their traditional place in patri-

archal culture, a transgression that at first seems trivial but soon turns them into gun-toting outlaws and that ultimately leads to death." In both films also, the women's journey takes them from the city to the country, where they have a communion with nature that makes them realize there is no going back.

The true glory of Thelma & Louise is that, in a phrase of the Roland Barthes era, it has made the culture speak. Not since the classics of the sixties and seventies, and perhaps Blade Runner (1982), have on-screen events so buzzed the volubility centers of so many viewers.

Special Feature:

Independent Cinema

Vol. 29, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 14–34.

The Short and the Difficult

Because of its analogies with drama and novel, the analyst of fictional narrative film can draw upon literally thousands of years of critical analysis—stretching back through Aristotle's Poetics , which laid out the fundamental critical categories (plot, character, spectacle, and so on) which go echoing on, even now, through the columns of your daily paper's film review section. Generations of Hollywood practitioners have put down on paper their accumulated how-to-do-it structural wit and wisdom. More recently theoreticians have attempted to deploy the machinery of linguistic and folk-tale analysis in order to understand how narrative films are put together. Though individual films continue to offer puzzles that tax even brilliant critics, there do not seem to be any greatly challenging theoretical lacunae in this area.

But astonishingly little work has been done on non-narrative forms. It is as if, in the history of literary study, virtually no attention had been paid to lyric poetry or the short story—only to novels and plays.

It seems likely that the structures of short, lyric forms are distinctly different from those of longer forms. The familiar, reliable devices of tension and suspense do not seem to apply, at least not in any easily recognizable way. Effects are often more akin to those of song than of drama. Visual considerations carry relatively more weight than in the story film where "action" tends to predominate, yet they are hard to describe and assess. In short, if we are to understand how the lyric film "works," we evidently need an entirely different sort of critical and theoretical approach than we use for the narrative film. Yet even the devotees of independent or experimental or "underground" cinema have failed to develop the new ideas that might enable us to understand such works on a more than impressionistic basis.

It is time to begin to try to remedy this situation. Here are several articles which attempt to deploy a critical methodology appropriate to non-narrative works. Perhaps significantly, two of these deal with films by Bruce Baillie—whose works are among those in our independent cinema that most resist paraphrase into verbal structures.

[Ed. note ]

Castro Street :

The Sensibility of Style

Lucy Fischer

I do not place the artist on a pedestal as a little god. He is only the interpreter of the inexplicable, for the layman the link between the known and the unknown, the beyond. This is mysticism, of course! How else can one explain why a combination of lines by Kandinsky or a form by Brancusi, not obviously related to the cognized world, does bring such intense response . . . granted the eye becomes excited, why?

Edward Weston, The Flame of Recognition

In making this entry of April 7, 1930, in his classic Daybooks , Edward Weston touched upon one of the central mysteries of our response to art: the manner in which pure forms can speak to us and impress us with a sense of their meaning. He characterizes the process as essentially mystical; but his consciousness of the materiality of form and structure seems to render him somewhat uneasy with that conclusion and he ends the passage much as he began, still questioning why.

It is thoughts of this nature which inflect our response to Castro Street , by Bruce Baillie. Like the works of a Brancusi or Kandinsky, it is fundamentally an abstract composition. For the rhetoric of pure line and form it substitutes the orchestration of photographic images treated as graphic elements within a complex montage design. And like the response to abstract art expressed by Weston in his remarks, our reaction to Castro Street involves a level of questioning. For the potency of its address inspires us to fathom the means by which its plastic abstractions communicate a sense of their significance.

On the surface, Castro Street presents an audiovisual tapestry in which footage of a railroad yard and oil refinery are subtly interwoven. Strands of imagery (of trains, smokestacks, industrial landscapes) appear on the screen to the accompaniment of a score of muted mechanical sounds. Discrete shots, however, seem devoid of autonomous, representational status. Rather each becomes a pictorial thread intertwined with others in the fabric of an overall pattern.

In this manner Castro Street creates for the spectator an experience which transcends the nature of its literal subject. As we watch graceful figures of train cars float by, and listen to the dampened sounds of engine-whistle screams, what we apprehend is not a picture of the industrial décor. Rather what we experience is something more vague and ethereal; it is a sense of profound and dynamic resolution.

What we perceive in our viewing of Castro Street finds reverberations in certain experiences Baillie seems to have had at the time of the film's creation.

We know that it was made during a severe period in the artist's life, one in which he felt as if he "were being born";[1] hence his cryptic epithet for the film—"the coming of consciousness."

Although the exact nature of that experience is known to Baillie alone, two enigmatic notes he made at the time offer us entree to his private sensibility as well as an approach to the aesthetics of the film. One appears in the form of a hand-written entry on a printed program for a screening of Castro Street and reads:

the confrontation of opposites (Carl Jung)

"the strength or conflict of becoming"[2]

Clearly the quote implies a relationship in Baillie's mind between the process of becoming ("the coming of consciousness") and the psychic confrontation of opposites. Its use on a program note suggests a further link between this conception and the formal structure of the film. This is substantiated by a reading of Baillie's catalogue description of Castro Street . For its language makes clear the sense of dialectical interactions imposed upon the configuration of the work:

Castro Street running by the Standard Oil Refinery in Richmond, California . . . switch engines on one side and refinery tanks, stacks, and buildings on the other—the street and the film ending at a red lumber company. All visual and sound elements from the street, progressing from the beginning to the end of the street, one side is black-and-white (secondary) and one side is color—like male and female elements.[3]

But Baillie's perceptions of the period were of a more complex and resonant character. For in addition to a sense of the confrontation of opposites, Baillie postulated their ultimate dissolution. Thus while the world presents apparent polarities, true consciousness affords the perspective from which to apprehend their resolution. This notion seems best articulated in a second note by the artist, one which constitutes an entry in his Castro Street journals:

now in my work, beyond sequence

beyond distinctions. . . .

way of conceiving reality

sequence/knowledge

beyond to

real consciousness (ego loss)

= agitation-less (loss)[4]

Clearly it is this sense of oppositions confronted and synthesized which one perceives as dynamic resolution in one's viewing experience of Castro Street . To inscribe this "way of conceiving reality" within the design of the film, Baillie has abstracted his photographic imagery to such a degree that it no longer presents an external depiction of reality. Rather it seems to have penetrated the surface of worldly appearance in order to render a vision of its deeper structures.

In grappling with the issue of our response to abstract art Weston had relegated its power to the realm of mysticism, thus avoiding a fruitful answer to the question. He had, however, concluded with a critical challenge, by asking "how else " we might explain art's cogent effect. In many ways an examination of Castro Street provides an occasion to engage that challenge. For rather than some "inexplicable link . . . between the known and the unknown," we find, upon analysis of the cinematic text, concrete relationships between Baillie's "metaphysical" postulations and his methods of plastic organization. Thus the dynamic of oppositions confronted and resolved which Baillie enunciated in his writings is manifested in the film on the level of formal interactions between color, movement, and sound.

While for Baillie the "coming of consciousness" arose in the domain of spiritual revelation, for the viewer of Castro Street it transpires in the realm of critical insight. For not only does the film afford us access to Baillie's particular sensibility; it occasions a consciousness of the means by which a sensibility can be articulated in a rigorous artistic form.

On all its complex tectonic levels the central mechanism of Castro Street involves the construction of formal oppositions in order ultimately to deconstruct them and dissolve the very notion of opposition itself. In this regard Baillie departs from the Eisensteinian conception of montage as collision. For while the Eisensteinian aesthetic calls for the intensification of oppositions, Baillie's editing style works toward the nullification of oppositions. If for Eisenstein "art is always conflict according to its methodology,"[5] for Baillie Castro Street encompasses a gesture in the direction "beyond sequence, beyond distinctions. . . ."

But, of course, to "go beyond" implies at first being "there"; and it is by examining the modes of articulating formal polarities within Castro Street that we arrive at a vision of how they are ultimately transcended into unity.

Castro Street is, above all else, a film of hyperbolic superimposition; from beginning to end it creates a uniform texture of densely enmeshed imagery. It would seem that implicit in the very mechanics of superimposition would be the kind of dialectical conflict that formed the basis of Eisenstein's theory of montage. After all, in superimposition it is as though the myriad oppositions that Eisenstein had posited as arising between the shots are encompassed literally within the frame itself.

If one examines the course of Baillie's career, however, one seems to witness a growing dissatisfaction with the dialectical quality of superimposition, and an evolution in the contrary direction. He speaks, for example, in disparaging terms of his use of "gross" superimpositions in Quixote and refers to his technical endeavor as "crudely trying to combine images on the screen at the same moment."[6]

Despite its perceived failures, however, Quixote did mark for Baillie the initiation of an attempt to neutralize the oppositions inherent in superimposition. It signaled a move in Baillie's work toward allowing diverse imagery to "share the frame."[7] This stylistic trend would ultimately culminate in the creation of Quick Billy in 1970, but Castro Street stands as a major aesthetic plateau along the way. The making of Castro Street in fact seems to have embodied Baillie's shift in formal direction:

I used two projectors when I edited. . . . When I first projected it, the two things together, it was a beautiful film just as it was. I projected on the same spot on the screen not side by side as it would be when I finally had done it.[8]

In Castro Street , therefore, Baillie veers from a heavily layered style of superimposition to a style of superimposed contiguity. Through this technique images are planted in neighboring segments of the frame—either by direct superimposition or by the more elusive strategy of matting.

Castro Street begins in darkness with Baillie's name handwritten across the screen. The center of the frame then opens up in muted color to reveal what appears to be a camera lens. The frame contracts once more and closes. A slit of light becomes visible in the lower portion of the frame. Gradually, the light pattern shifts and we realize that what we have seen has been light reflected off a glass surface, through which we now vaguely perceive the outline of smoke. The glass is then pulled away and bares the image of industrial smokestacks. Two matted areas (in upper and lower right-hand corners of the frame) fade in. Each one records a slightly different view of a commercial landscape as seen from the window of a moving vehicle. Next a faint diagonal wipe takes away the large-scale image of the smokestacks; the twin mattes remain. Another portion of the frame then unfolds to display a more defined image of industrial chimneys. This matted area travels upward in the frame while simultaneously the two earlier corner mattes fade out. Eventually a diagonally composed negative image of a high-tension wire (as seen from a moving car) fades in and inhabits the frame with a circular matte containing the image of a smokestack.

What becomes apparent from this description is the seamlessness of Baillie's design (a seamlessness which makes the attempt at verbal translation an act of critical hubris). Rather than creating a sense of superimposed images in dialectical

conflict, Baillie works against this to create a sense of coherent union. He embeds one image within another and fuses them so that they "come out as though they were married."[9]

Perhaps the most mystifying example of this technique occurs towards the end of the film. The sequence begins with a low-angle shot of a man standing on an industrial machine against the background of a blue sky. At a certain point the center of the frame gapes open (like a wound) and shows us a yellow-tinted image of a metal pipe. Magically the image of the man (which has become the matting environment of the second shot) transforms to a monotone blue, then to a solid black, and finally returns to the image of the man. The central yellow area then closes up and disappears.

It is this organic sense of the connection of shots that is so crucial to the power of Castro Street —the sense of a shot opening up and closing to reveal a second shot, much as the iris of the eye expands and contracts to delineate the boundaries of the pupil.

Thus we find that the heightening of shot distinctions that traditionally occurs in layered superimposition becomes an annihilation of distinctions in the kinetics of matting. Matting is, after all, the quintessential Hollywood illusionist technique; it allows the fluid combination of images without the telltale traces of superimposition. It accomplishes the merging of images while blurring our consciousness of the act of fusion.

The intention to combine shots was at points inscribed within the very process of shooting the film itself. For in recording images Baillie used his black-gloved hand to reserve spaces which would later be occupied by other shots.

Concomitant with the elimination of shot differentiation in Castro Street is the weakening of temporal distinctions. Often the images so joinlessly share the frame that it is difficult to establish whether they were photographed simultaneously as one shot or represent two separate temporal moments joined only in the editing process. As Baillie has phrased it in relation to Quick Billy , his matting strategy is one of overlaying imagery so that it "looks like it was all invented or occurring at the same moment."[10]

But it is not purely the technique of matting that creates the sense of image resolution; it is also Baillie's means of rhythmically choreographing the images in succession. What one notices in analyzing Castro Street are the "transactions" that take place between shots. As one matte fades out, another, perhaps, fades in. Thus one set of imagery is continually exchanged for another in intricate patterns of balanced and symmetrical progression. At one point in the film, for example, we have a shot involving two layers of superimposition. The first presents a negative image of the ground, and the second a negative representation of trains in motion. As the latter image remains on the screen the former fades out; but as it does so it is replaced by a shot of flowers in close-up. Through this technique of

Raw footage showing matting process used in Castro Street

(Canyon Cinema)

the interchange of imagery, shots are joined not only by their compression within the boundaries of the frame but by the kinetics of the editing process itself. Baillie seems to be alluding to this sense of montage when he formulates his notion of the cut as the moment "when one thing becomes another in succession."[11]

This sense of one thing becoming another is further accentuated by the fact that the pace of movement from shot to shot in Castro Street is one of lulling uniformity. Thus the rhythm of a tracking shot on one image level of the frame will be synchronous with a panning action on another. The similarity of tempo works to nullify the disjunction in form and subject.

Not only does the matting process minimize the boundaries between discrete shots, it works as well to soften the rigid quadrilateral borders of the frame. Thus Baillie utilizes the biomorphically shaped matte provided by his hand to "get away from geometry" and create a "moving amorphous form."[12]

Another formal opposition that Baillie simultaneously activates and neutralizes is that of black-and-white versus color. His engagement of the tonal conflict is even apparent in his description of the film: ". . . picture and sound taken on one street—the color side female, the black-and-white side male, in opposition (creation)."[13]

But it is characteristically ambiguous that Baillie has chosen a sexual analogy to illustrate this formal polarity. For implicit in the invocation of discrete sexual elements is the possibility of their fusion in sexual union.

Most often in Castro Street tonalities are opposed through the technique of superimposition; thereby, one of the layers of imagery will be recorded in color

while the other will be shot in black-and-white. Frequently this disparity is heightened by the fact that the black-and-white layer has been realized in high-contrast negative. One example of this pattern occurs midway through the film in a multi-tiered composite image of objects in movement. On one layer a yellow train car moves left to right across the screen while on another a black-and-white train wheel floats by in the same direction.

Given this virtually textbook case of montage "collision," what accounts for the fact that our experience of the tonal dialectics of Castro Street is one of essential tranquillity? It would seem that several formal strategies are at work to dampen the potential sense of chromatic tension.

First of all, Baillie begins the film in highly muted color, the kind that barely reaches consciousness as such. It is a ghostly color that forms a vaporous immaterial hue, like that of a rainbow. On this level Baillie's subdued chromatics tend to accentuate the ethereality of his images, as well as to blur the perceptual distinction between color and black-and-white.

Having established this diluted tonality, Baillie then begins quite carefully to introduce "true" colors, almost as "characters" into the abstract narrative. Red is the "star" of the film; it comes as the first rich color on the caboose of a train and it reappears in the middle of the film, at first anamorphically, and then as a red steering wheel. Characteristically it closes the film with the climactic image of the dome-roofed lumber barn at the end of the street.

Significantly, blue and yellow play supporting roles as the other major colors in which Castro Street is painted. Blue appears as the hazy background in which so many images are planted and also as the sky. Yellow hues occur on industrial pipes, in an anamorphic vision of rocks, and, most strikingly, in a field which neighbors Castro Street.

Blue, yellow, and red are, of course, the primary colors. Thus Castro Street is tinted in archetypal tones: black (the absence of color), white (the presence of all colors), and the primary colors (those which are parents to all the rest).

Certain theoretical speculations arise from this formal choice. First of all, it seems telling that in utilizing black-and-white Baillie saw fit to invert their values through negative printing. In so doing, the comfortable opposition of the absence or presence of color is turned on its head and disarmed. Moreover, at times during the film Baillie chooses to dissect white light through prismatic lenses, thereby revealing the presence of variegated spectral hues in its apparently monochrome band. Finally, the selection of primary colors adds further complexities to the tonal structure. For although primary colors in "montage collision" create all other chromatic hues, theirs is essentially a seamless union. As R. L. Gregory explains it in Eye and Brain: ". . . two colours give a third colour in which the constituents cannot be defined. Constituent sounds are heard as a chord and can be separately identified . . . but no training allows us

to do the same for light."[14] Thus primary colors work in montage in a manner similar to that of Baillie's imagery: distinctions are apparently there and not there at the same time.

Another formal conflict which is engaged and then released within the dynamics of Castro Street is the directional opposition of movement. Once more its primary means of formulation is the technique of superimposition. Throughout the film when images share the frame we often find that they embody movement in opposing screen directions. Typical of this pattern is a shot involving directly superimposed images of trains in motion: one image layer moves horizontally left to right, while the other moves diagonally into the depth of the frame. Perhaps the most hyperbolic instance of editing for antagonistic movement comes rather early in the film. A variety of moving-train images in high contrast negative are edited in split-screen format so that they seem to crash together in the central axis of the frame.

This moment, however, in its climacticism, is essentially uncharacteristic of the mode in which Baillie handles movement in the rest of the film. For in general in Castro Street Baillie works to resolve rather than heighten the sense of polarity of movement; and he does so by employing a variety of techniques. To begin with, when editing images of opposing motion Baillie most often juxtaposes movements executed in quasi-identical rhythms. Thereby the synchronicity of the pace of movements seems to blur our recognition of their antipathetic directions. Rather than collide, the images tend to cancel each other out and leave us with a sense of quiescent stasis. One is reminded of an exchange between Baillie and an interviewer that appeared in Film Comment:

BB: I have to say finally what I am interested in, like Socrates: peace . . . rest . . . nothing.

FC: No movement at all?

BB: Nothing. Okay, that's enough.[15]

Exceptions do occur when Baillie utilizes a sense of syncopation in the rhythm of objects in motion. Ironically, however, the example that comes to mind is one in which the objects depicted are moving in the same direction. Toward the end of the film we have an image of a right-to-left tracking shot over signs plastered on a wall. Next the image of a train moving in the same direction fades in, superimposed. The pace of the train, however, is slower than that of the track and at points its movement seems to be reversed.

Thus when directionally contrary movements are involved Baillie works to buffer their sense of opposition; where similarity exists, distinctions are maintained. "Different" is the "same" and the "same" is "different" until the very poles of the semantic equation become meaningless.

But movement in Castro Street involves a greater subtlety as well; for central to our experience of its ambiguity is Baillie's blurring of the distinctions between the camera and its object as a source of movement. This is possible because of the phenomenon of relativity of movement in film. As Rudolf Arnheim explains it in Film As Art:

Since there are no bodily sensations to indicate whether the camera was at rest or in motion, and if in motion at what speed or in what direction, the camera's position is, for want of other evidence, presumed to be fixed. Hence if something moves in the picture this motion is at first seen as a movement of the thing itself and not as the result of a movement of the camera gliding past a stationary object. In the extreme case this leads to the direction of motion being reversed.[16]

Thus throughout Castro Street even the secure notion of directionality is confounded. We may see objects move by from screen right to left but more often than not, examination reveals them to be stationary objects photographed by a camera moving from left to right.

Inherent in this paradox are certain theoretical overtones. For by employing this perceptual ambiguity Baillie generates confusions between the traditional antipathies of stasis and motion, and left and right. And the reason that these polarities can be questioned is that he has dissolved a third and more profound distinction: that between the perceiver and the perceived. Thus because of the ambiguity concerning whether it is the perceiver (i.e., the camera eye) or the object perceived (or both) that is in motion, it is possible that what is moving within the frame may, in fact, be static; and what "moves" left may have been photographed by a camera moving right.

A unifying sensibility is also apparent in two final parameters of the film's construction. Castro Street embraces a variety of modes of vision yet works to resolve any tension engendered by their disparity. Where "clear" images prevail, Baillie works against their sense of realism and definition by using matting, damped coloration, negative printing, or the slurring effect of an improperly threaded camera.[17] Where anamorphic photography occurs, Baillie often subverts its sense of abstraction by removing the distorting, mediating gel and revealing the subject in sharp focus. Obviously, the mutually exclusive perceptual modes implied by the polarities of color versus black-and-white, negative versus positive registration, are contained as well within the incorporative vision of the film.

In many ways the confounding of styles of vision mirrors the conflation of perceptual modes that we find in Baillie's diaries and notebooks. Just as clear and anamorphic sections intermix within the film, so fragments from waking and dreaming states flow together in the journals.

Baillie also works in Castro Street to nullify any sense of disjunction between the sound and image tracks. He does so, however, without resorting to the facile technique of illusionistic sync sound. Rather Castro Street creates a highly abstract sound track that, while never illustratively coinciding with the images, provides an almost synaesthetic aural equivalent for them. The texture of the sound track parallels that of the image and follows a similar "narrative" line. In sections where the editing of the shots creates a regular lulling rhythm (e.g., the opening of the film), the sound track heightens this mode of temporality by intoning monotonous chugging train sounds. At moments of visual climax (e.g., when a mass of superimposed images "crashes" in the center of the screen) the sounds take the form of louder, harsher, shrill whistle screams.

This formal unity of sound and image is characteristic of other films by Baillie. The highly montagist section of Mass which presents an assertive visual collage translates this strategy to the aural parameter as well. Thus Baillie accompanies images from old movies and television with fragments of dialogue from commercials, newscasts, and television dramas. The total fusion of sound and image in All My Life (which consists of a single tracking shot of a fence accompanied by Ella Fitzgerald's rendition of the title song) is apparent in Baillie's characterization of the film as "a singing fence."[18]

Just as sound-to-image dichotomies are blurred in Castro Street , so sound-to-sound distinctions are elided. Disparate mechanical sounds blend together and those ostensibly from the train yard merge indistinguishably with those from the oil refinery, forming a unified aural composition.

Ultimately even the subject matter of Castro Street reveals its own impulse toward bracketing contradictions. Like the industrial landscape of Red Desert the mise-en-scène of Castro Street stands as a hybrid cross of barren technological sordidness and stark arresting beauty. As P. Adams Sitney noted: "When we look at the whole of [Baillie's] work we see in alternation two incompatible themes; the sheer beauty of the phenomenal world and the utter despair of forgotten men."[19]

Yet central to the magic of Castro Street would seem to be its power to make the incompatible compatible—to contain contradictions both on a formal and thematic level. It is, perhaps, even more profoundly the point of Castro Street to refuse us the comfort of such categorical polarities at all. One is curiously reminded of Eisenstein's discussion of Japanese culture and of his analysis of their traditional synthesis of the oppositions of auditory and visual material:

audio visual relationships . . . derive from the principles of Yang and Yin, upon which is based the entire system of Chinese world outlook and philosophy . . . Yang and Yin . . . depicted as a circle, locked together within it Yang and Yin—Yang , light; Yin , dark—each carrying within itself the essence of the other, each shaped to the other—Yang and Yin, forever opposed, forever united .[20]

Bruce Baillie's Castro Street

It is precisely this sense of unity revealed in disunity, of resolution in opposition that reigns supreme on all levels of Castro Street —on the level of shot-to-shot superimposition, directionality of movement, tonal composition, sound-image relation, and spiritual sensibility.

As Baillie has told us, Castro Street is a film "in the form of a street." Implicit in this notion seems the concept of the film as path, or even journey. We know from Baillie's autobiographical notes that the film was for him a "coming of consciousness—a recognition of the confrontation of opposites as part of the 'conflict of becoming.'" But throughout the film itself, embedded within the opaque imagery, have been signs which seem to bear hidden messages relevant to Baillie's concerns. Thus the graphic "X" of the railroad crossing sign seems a symbolic diagram of the structure of the film (which is, after all, an intersection point of formal and thematic oppositions). And the appearance of the railroad name of "Union Pacific" emblazoned on a passing car seems tinged by a vague, metaphysical resonance.

But it is the final emblem of the film that warrants our most attentive reading, and it appears in the form of a sign for Castro Street that floats by on the

screen. For contained within the graphics and articulation of that closing image is inscrolled the very dynamics that have informed the style and meaning of the film. It is an image that speaks a language of resolved oppositions: It is one of the final images of the work yet presents to us for the first time the title of the film. It is recorded in black-and-white negative yet is superimposed over a positively registered red-colored barn dome image. It moves across the screen, yet was, of course, in reality, static . It drifts past us right to left but depicts an arrow which points left to right.

Thus the sign which bears the name of Castro Street is clearly more than a street sign. Its pregnant mode of presentation proposes it as truly exemplary of the formal and thematic energies of the film.

The Structure of Lyric:

Baillie's to Parsifal

Alan Williams

It's difficult to say exactly where or how To Parsifal is a lyric film and where or how a narrative work. For this reason, ordinary critical vocabularies (based on certain "types" of films) do not apply with much usefulness to Bruce Baillie's abstractly assembled color images, nor to the nature and functions of his sound track. To get a sense of how this film works it will be necessary first to break it down, outline it, in order to see how the (implied) viewer puts it together.[*]

The 16-minute film falls neatly into two nearly equal parts, separated by fades to and from black.

Part one depicts a sunrise, a journey out to sea in a boat, then gulls flying around the boat while fish are cleaned, and finally the journey back and the reappearance of land. This is, narratively, a reasonably clear presentation of a fishing voyage; the only strange thing, informationally, is the absence of human beings (except for the hands seen cleaning fish). In part two the setting changes from sea and coastline to a mountain forest traversed by railroad tracks. Workmen are seen repairing the tracks, after which a train passes through the forest while a nude woman stands nearby. The woman washes herself in a stream as insects move on ground and water. Then the workmen are again seen repairing the tracks; a train appears and a man's hand pulls the woman away from the camera as the train continues through the forest, illuminated by a setting sun.

The two parts function as one larger unit by similar patterns of development and by a strong sense of temporal progression. Part one begins at sunrise and seems to end during the afternoon. The second part begins at some time in the morning and ends with a sunset. Whether we are to take the film as occurring during a single day or during two days seems beside the point; the work has an almost mythic sense of time. As the beginning of part one and the end of part two are connected by the presence of the sun, the end of the first part and the beginning of the second are connected by the presence of mist (subtly underlined by the foghorn on the sound track during the darkness which separates the two units).

Both parts exhibit a circular (symmetrical) construction which also contributes to the mythic—ritualistic—aspects of the work. This is most striking

The "viewer" here, strictly speaking, means the principle of possible meanings built into the work, the ways in which structures outside the film must be brought to bear in order for its reading to be coherent, to make "sense" of some sort. In this way, the text needs the implicit "viewer."

From the opening of Baillie's To Parsifal

(Canyon Cinema)

in the ABA movements of the fishing voyage: land to water to land again—voyage out, fish and gulls, voyage back. There is another large ABA structure at work in part one, not specifically connected with the story as such (though it contributes to the overall formal structure). This is the alternation on the sound track between music and "natural" sounds. The film begins with a coast-guard weather report, recorded (seemingly) on the boat. This continues to the fourth shot of the film, where it slowly fades out as music fades in—an excerpt from Wagner's Prelude to Parsifal . This music continues almost until the end of part one, when foghorns and boat noises are heard, continuing through to the dark screen which divides the work.

Part two is more complex, as may be seen merely from its density of shots (65 as opposed to part one's 43) and from the more frequent alternations on the sound track. Nevertheless, the same formal principles are at work. The workmen and the train appear twice, at the beginning and end. The middle portion (woman bathing and the insects) is not repeated and does not incorporate any elements which precede or follow it—except for the woman, who is seen in

a different place, in a different light (this being the brightest tonality in part two), and from a different camera angle and position. The principal elements new to the repeated "A" section in part two are the man's hand and the sunset, but both have their equivalents in part one: the hands which clean the fish, and the rising sun. What is lacking in the forest scenes is a means of "explaining" the images, as part one can be called a fishing expedition. (We will see later that much clarification of this part's "story" can be obtained by relating it to Wagner's opera.)

The sound track for part two is more complex than that of part one, but it still proceeds by an alternation of music and "natural" noises. There are four sections of music, drawn from the body of the opera, which alternate with three types of sounds associated with the train: the voices of the workmen, wheels on the tracks, and the train whistle. This grouping is similar to that in part one where all "real" sound was connected with the boat. Thus we can represent the structure of part two as an expansion of the circular pattern already noted in connection with part one. If A signifies music and B natural sound, the pattern is AB ABA BA. Part one begins and ends with natural sound-effects, whereas part two begins and ends with music.

So far I have been indulging in what would most frequently be called a "formal" analysis of To Parsifal . The question most frequently raised by such a procedure (and rightly so) is: where does it lead? What does this analysis say about the text and its production of meaning? The ABA structure (and its expansion) which we have isolated, first of all, does contribute to the "mythic" feeling of Baillie's film. But more importantly, the heavy formal equivalences between the two sections of the work permit us to draw some tentative conclusions about the visual and thematic equivalences between these sections.

The boat with its wake and the train with its track have similar places in the formal configurations of parts one and two. The fish and the woman, as well as the animals that surround them—gulls and insects—appear only in the "B" sections of the two parts. Constant in both sections are the functional equivalences between ocean and land, masts and trees. Thus, the formal parallels we have noted have repercussions on what might be termed a thematic level. Significantly, the visual treatment of these same elements (particularly masts = trees, wake = tracks, and ocean = land) matches up through composition within the image.

These tentative conclusions will have to suffice until we have investigated the formal structure of the film a bit further. The patterns we have observed have analogues at levels beyond the global movement of each section of the film. Our brief summary of the fishing expedition as presented in To Parsifal may be summarized as follows:

1. Prelude (sunrise): land, water, boat

2. Journey out to sea

3. Gulls and fish cleaning

4. The journey back

But are there any other criteria than narrative structure which make this grouping more valid than any other? For example, how do we separate segments 1 and 2, by what principle and at what moment?

There are some important formal principles differentiating the various segments which we have identified. Aside from shot content (which is still quite important), these segments are distinguished by emphasis on movement within the frame (segments 1 and 3) and movement—generally tracking—of the camera (segments 2 and 4). This is a distinction which will remain important for the second part of the film. Segments 2 and 4 are composed almost exclusively of tracking shots taken from the side of the boat. To this moving depiction of immobile objects is contrasted the fixed-camera shots of the moving sun, grass, and hands cleaning the fish in segments 1 and 3. This general tendency is contradicted by occasional shots, but as an overall structure device it remains remarkably constant.

The passage from one type of shot (and segment) to another is accomplished so smoothly as to be almost imperceptible. Shots 8 and 9 of the film, which demarcate what we have termed segments 1 and 2, are a good example. The camera, fixed, shows a close-up of water in motion, all white, taken from the shore. The new shot begins as apparently the same thing, until an upward pan to smoothly moving blue water reveals that we are now tracking with the boat, the first of a series of such shots which will continue until the beginning of the third segment, where lateral tracking is either absent or considerably de-emphasized, depending on the shot.

Another way in which these segments are differentiated is by their internal coherence. When we examine groupings of shots in To Parsifal we find a precise, almost abstract way of juxtaposing images and forming larger units with them. Two principles of coherence seem to be at work (these are common, it should be said, in many types of film). The first we might call a principle of alternation: given two types of shots—from different angles, distances, of different subjects, and so on—the two elements may alternate, ABAB and so on. The second principle we might term variation by distance: given a single subject or type of shot, the camera distance may change from long shot to medium to close-up or vice versa. In To Parsifal these two procedures occur sometimes independently, sometimes in combination. Breaks in the narrative structure and significant individual shots are emphasized by the absence of these two types of coherence.

Described in this fashion, these two principles of organization may well seem artless and mechanical. Their action within the film, however, is subtle and balanced. Perhaps the easiest way to demonstrate the work's artful manipulation of such formal principles is to study the "fish and gulls" segment in part one. The core of this segment is formed by the perfectly symmetrical development of images of the fish being cleaned:

Medium shot, camera up: many gulls flying by the boat; the rope swings briefly into the foreground, with water seen at the end of the shot (20 seconds)

Extreme close-up, camera down towards table: bloody fish's mouth, very red (1.7 seconds)

Medium shot, up: sky and a gull flying alongside the boat, mast and cable (11 seconds)

Close-up, down: fish's body, knife cutting both the frame and the fish's belly (3.3 seconds)

Medium close-up, down: three fish on a table, hands cleaning one of them (6 seconds)

Close-up, down: one fish, split open; the knife passes through its body and the frame of the shot (4.0 seconds)

Medium shot, up: sky and gull, mast and cable (same set-up as the third shot of this series; 2.7 seconds)

Medium close-up, up: gulls flying, sky, no boat parts (1.7 seconds)

Extreme close-up, down: a fish's head, its yellow eye in the right center of the frame (1.3 seconds)

Medium shot, horizontal: empty sky framed by a doorway; the gulls fly in and out of the frame (8.3 seconds)

We may see that these shots are centered on the most distant (medium close-up) and longest (6 seconds) image of the fish. This shot is surrounded by briefer, closer images of fish, and this group of three is in turn surrounded by other shots of fish and of gulls, arranged symmetrically.

Thus, the appearance of the fish is regulated both by alternation with shots of gulls and by variation by distance. This new material—the fish—is introduced in a manner typical of the film as a whole: alternation is the rule, with subjects and formal procedures held over from the part of the film which immediately precedes. This is true, for example, in the distinction which we already made between movement in the shot (fish and gulls) and movement of

the camera (tracking with the boat): the latter does not totally disappear in this segment but is phased in and out through the principle of alternation.

The use of color and shot duration in this segment is also characteristic of the development of the film as a whole. The first introduction of the fish motif is accomplished in a brief shot, particularly short in comparison to the 20-second shot which precedes it. The tonality of the film to this point has been largely blues and greens, with some yellow in the introductory segment, and the first shot of the bloody fish introduces an extreme hue of red which, in contrast, is nothing short of shocking. The last (equally brief) extreme close-up of the fish introduces a brilliant yellow not seen previously.

This "fish and gulls" segment is more rigidly developed than others in the film, in keeping with its central thematic importance. The opening (what we have labeled segment 1 of part one) of To Parsifal , on the other hand, shows much freer construction, even though it is still based on the same sorts of development and linking of images. This segment consists of:

Long shot, horizontal (vertical motion with boat): silhouette of boat on left in foreground; water, shore, sky lit by sun behind hills; title fades in and out over boat (27 seconds)

Medium long shot, horizontal: grass, hills, sky lit from behind hills (5 seconds)

Very long shot, horizontal: grass rustling, fence, hills, grey sky (8.6 seconds)

Long shot, horizontal (vertical motion with boat): boat parts in right foreground; water, hills, the sky lit by more light than previously (20 seconds). Dissolve to:

Long shot, horizontal: grass in foreground, hill, sea, sky (looking towards the sea; 10.8 seconds)

Long shot, horizontal: grass in foreground, moving furiously, hills, sky, no water (9.8 seconds)

Medium long shot, horizontal: rocks (one in foreground at right), sea, sky (10 seconds)

Close-up, downward camera: rocks, water in rapid movement, no sky (6.4 seconds)

We can see the principles of alternation and variation by distance at work in these shots. The second image, for example, appears to be (though from its lack of movement evidently is not) a closer shot of the hill with the sun behind it seen from the boat at the film's very beginning. Shot 3 introduces a new type

of image—hills and grass, not at dawn—and is followed in shot 4 by a return to the elements of shot 1. Shots 5, 7, and 8 are successively closer views from a new vantage point (looking towards the sea) of rocks, shoreline, and water. Shot 6, on the other hand, is a closer view of the same elements seen in shot 3. In terms of content we could schematize this series as AABACBCC. This complex yet symmetrical pattern recalls the careful construction of baroque music or certain types of rhyme schemes in French poetry. Lest we give the impression of too much formal rigor we should note that duration of shots varies considerably in this segment. In general, it follows the film's tendency to accord more running time to more distant or complex shots at the expense of close-ups or simple visual groupings.

One more comment should be made about this opening to Baillie's film. The shots which we identified as types "A" and "C" are essentially the same type of shot taken from two directions, which will be the two directions of the film as a whole. Shots 1, 4, and presumably 2 are taken from the sea looking toward shore and rising sun. Shots 5, 7, and 8 are taken from the shore looking toward the sea. Thus the division we may note between shots 4 and 5, which is the point at which the segment folds back on itself formally (this emphasized by a dissolve), is explicable as the meeting of water and land—and the two different directions (and angles—up and down) from which they can be viewed. (Shots 4 and 6 are distinct in this series by including no reference to the sea or to direction at all; they seem to have been taken at an entirely different location and time of day. Indeed, they seem to refer to the second half of the film, particularly since they are strikingly similar to several of its shots.)

The second half of To Parsifal is, as we noted, more complex than the first. It is possible to carry out the same operation of segmentation as we did with part one, though the result is a bit less elegant. What is more important here is to explore further the structuring principles of the work and its possible meanings.

In examining the overall structure of parts one and two we posited an equivalence between the nude woman and the fish being cleaned. As the position of the woman will lead us into the central problems of an interpretation of Báillie's film, we will note the stages of her presentation. She first appears in a very brief close-up of the back of her head. This shot is surrounded by two almost identical shots of the train in motion. This procedure is comparable to the position of the first close-up of the fish (also, significantly, of its head), which is surrounded by shots (looking up, as with the train) of gulls. Use of color is analogous in the two cases: the red of the fish is the first use of this color in the midst of dominantly blue and white images, while the woman's blond hair is an almost equally great contrast to the muted greens and browns of the shots which surround it. Both woman and fish are introduced in shots

of such short duration that it is only with their second, longer appearances that the initial shots can be identified, in retrospect.

But the development, on a shot-to-shot basis, of the motif of the woman does not continue to parallel that of the fish. Later, where we might expect a more distant shot of the woman's hair and body, we see instead a tracking/panning shot of the woman as seen from the train. There is only one similar shot, in terms of movement, in the film. This is in part one, where we see a gull on the water from the moving boat. Paradoxically, these links establish a sort of formal equivalence between woman and gull, as well as between train and boat, ground and water.

In the center of what we termed the large, "B" section of part two the woman reappears. Shots of her are cut into a series depicting mainly water-strider insects on the mountain stream. She is in the water in these shots, and no train or tracks are visible. Again, she appears only twice, briefly, and then is not seen for ten shots, when she is shown in medium shot, from the back as before. This is a more distant shot from the same position as the previous ones, and is followed later by a return to the original distance, giving a progression by symmetrical variation of camera distance similar in method to the development of the images of the fish in part one.

Finally, in the return to the "A" segments of part two, the woman is again alternated with shots of the train. These images work by an opposition of camera angles similar to that in the fish/gulls segment of part one: shots of the train (and from the train) are angled up, whereas shots of the woman emphasize a downward angle.

Near the end of the film, we see the first shot of the man's hand, which will be present in all subsequent images of the woman. The last three shots of woman and hand (always alternating with shots of the train) are particularly intriguing because they introduce a change of direction. These are the first images of the woman from the other side of the "action"—of her belly and neck rather than back. In the first shot of this type, leaves and foliage frame the grasping hand, a composition which recalls the first appearance of the train in part two, where small leaves on the edge of the frame surround the more distant train. This comparison implicitly gives support to the idea of the train as "masculine" principle—as phallus. We should note in connection with this shot that the hand is not pulling the woman out of the path of the train, as has been suggested in some commentaries on the film. Rather, it pulls her out of the stream (and, if we are to believe the matches established previously in the film, towards the train). But here we encounter problems beyond the level of segmental structures and formal oppositions.

The question arises: to what extent can we use this brief study of structural features of To Parsifal as part of an attempt at a general interpretation of the

From part two of Baillie's To Parsifal

film? To approach this problem we must begin by placing the film in a larger context, that of the Parsifal legend. For Baillie has, by the title of his film and by the use of music from Wagner's opera, grafted his relatively abstract images onto a traditional Western narrative. In its essentials the Parsifal story begins with a kingdom mysteriously laid barren by the illness of its ruler, the Fisher King. The king suffers from a wound of unknown origin, and the land of his kingdom is infertile by response. The king and land can only be restored to health by the quest of a pure knight for the Holy Grail, the vessel in which Christ's blood was gathered during the crucifixion. The knight must resist the seductions of a temptress (Kundry, in the Wagner opera) and perform various acts of bravery.

Even from this brief summary we can see points of congruence with Baillie's To Parsifal . There is a "wounding," as we have seen, quite prominent in part one—that of the fish. What better representation of the "Fisher King"? And a naked woman appears in part two—accompanied on the sound track by an excerpt from Act II of the opera, in which Kundry sings seductively to Parsifal to stay with her and abandon his quest. We could postulate, therefore, that part one of the film depicts the wounding of king and land and that part two concerns the quest for redemption and fertility. But this interpretation raises many questions. Should we therefore see To Parsifal as an anti-technology film, depicting the "rape" of nature by man's interference? Who or what in the work is Parsifal? Why the presence of the train in part two? Is the quest successful? These questions can only be approached in conjunction with a consideration of internal relations in the film and its place in the larger body of Baillie's cinema.

We can begin by considering the parallels established between parts one and two. These parallels have profound effects on meaning (indeed, such structures

create meaning). The insistence on modes of transportation, on water, the similar introductions of woman and fish, the resemblances between many shot-types and visual elements common to both parts, the repeated oppositions established by parallel editing between up and down, moving and non-moving shots, and so on—all suggest that the two parts of the film depict similar states, or perhaps different aspects of the same problem.

If part one depicts the wound (rape) of nature and part two the quest for renewed fertility (and it would seem that this is a reasonable assumption, considering the mythic context Baillie has given the film), then the parallels between parts one and two suggest that in To Parsifal the rape of nature and the return of fertility are different aspects of the same act. We should note in this regard that some versions of the Parsifal legend indicate that the knight who must search for the Grail is also originally responsible for the wounding of the Fisher King. This interpretation—the continuity and interdependence of the wound in nature and the quest for health (the "freeing of the waters" in the legend)—would help explain the establishment of a mythic time in the film, marked by sunrise and sunset. The work depicts not a closed series of events but a cycle, a process continually in play, and not a redemption found once and for all.

This set of meanings is put in explicitly sexual terms. Many aspects of the film's structure suggest a basic division of its elements into cultural stereotypes of masculine and feminine forces—yin and yang. The woman and the fish are both strikingly associated with water and are presented as comparatively static ("passive"). They both are only seen from horizontal or downward camera angles. The boat and the train, on the other hand, both ride over land and water, on tracks and wake, and are presented as causing motion ("active") and are only seen in horizontal or upward angles of the camera. A number of shots suggest that boat and train leave not only marks but wounds on the surface of land and water. We might generalize from these associations to see nature as a "feminine" element (given the prevailing mythology of our culture) and technology as a "masculine" one. But this notion in no way makes To Parsifal an anti-technology film. Rather, the work seems to be a song, a hymn (in ideologically suspect terms . . .) to the cycle of infertility and fertility, wounding and healing, intercourse and childbirth.

We can find some justification for this point of view in the singularly sexual connotations of many images in the film. Examples in part one include the boat's masts, the knife which passes through the red lateral opening in the fish, and the boat passing under the bridge. In part two we might cite the train seen moving through the framing leaves, the trees set off at a marked upward angle, the workman's wrench by the tracks, and, of course, the man's hand clutching the woman's body and the long tracking shot from the train forward through the trees—after the woman has been pulled from the water (like a fish).

To examine these hypotheses, it would seem reasonable to broaden the corpus under examination to include all of Baillie's films. Is what we have suggested about To Parsifal contradicted or supported by the structures and themes of his other work? To Parsifal (1963) is the first of three films concerned, as Baillie has said, with problems of "the hero." The other two works in this series are Mass for the Dakota Sioux (1963–64) and Quixote (1964–65). One of the major problems of To Parsifal is finding in it any "hero" at all. Likewise, in the two other films there is no single Hollywood-style protagonist. Rather, the heroes of these films are collectivities, mythically linked in each case with a legendary hero—Don Quixote and Christ—just as the Parsifal story supports the images of To Parsifal . Thus Baillie's conception of the hero in these works seems not that of any individual actor , but rather of a force at work in many guises. The only existence allowed the "hero" as distinct individual in Baillie's cinema is in the myths which structure the films. But the forces at work in To Parsifal seem hardly human at all. The two centers of the film are the boat and the train. If a hero is to be found it would seem that they are its active representatives. The boat journeys to sea and causes (in terms of what we see) the wounding of the fish; the train passes through the forest without stopping as a nude woman stands seductively by the tracks. These are precisely the actions of the legendary Parsifal. The hero is the "masculine" principle here embodied by technology.

Despite the frequent beauty of its images of nature, Baillie's cinema is not one of protest and contestation of "progress." Castro Street (1966) seems particularly relevant here, because its central image is the train. Shots of switch-engine, street signs, factory buildings, and other elements of the locale are superimposed in a contrapuntal fashion; nothing in the film suggests any commentary other than a reveling in the abstract beauty of these forms. Baillie has said that one image of a train engine near the end of this film represents "for the film-maker the essential of consciousness." Tracks and a cablecar also figure prominently in his first film, On Sundays (1960), though their thematic position in that film is not clearly defined.

We should note, finally, in considering To Parsifal in the light of Baillie's work in general, a pervasive differentiation between male and female. Whether these films should be considered as overtly sexist is not a concern here. We should note, however, that all of Baillie's films indicate an adherence to cultural stereotypes of masculinity and femininity which we found helpful in decoding To Parsifal . In particular, the women in On Sundays, Valentin de Las Sierras , and Quick Billy (1971) are presented as passive objects of men's more active interest.

Thus, we can find in Baillie's other work three of our centers of interest in reading To Parsifal —the hero, technology, and male/female differentiations.

All these topics seem to reinforce our analysis of the film: through a traditional grid of "masculine" and "feminine" elements, the work celebrates the eternal cycle of death and rebirth, sterility and rejuvenation.

It remains to be seen how we can justify the project of such a reading. None of these ideas are literally "in" the film. At the beginning of this study I attempted to read the implicit viewer into the film text. The viewer, it will be recalled, is that system or set of systems which may "make sense" of the work. This operation is far from being innocent or "natural," for the text by itself is a set of fragments. Without some notion of the viewer, criticism risks reducing any text to its discontinuities.

There is a certain sort of structuralist criticism which pretends to totally evacuate the viewer from the study of film. Such an operation is, to my way of thinking, illusory. To pretend that in film the spectator is wholly passive is sheer nonsense, a form of elitism worse than the bourgeois individualism of the "every person sees his/her own film" point of view. Thus, in this study of To Parsifal , I have frequently referred to the "viewer," but not to my own or anyone else's direct experience of the film. Rather, what is here called the "viewer" is in fact the set of ways of giving meaning to the work. The film text needs the spectator, and the spectator's function is to create coherence from it.

To Parsifal , like any film, cannot be studied without first giving an approximation of how it is read. In this study I have suggested, hopefully, part of this operation. The objective of structuralist criticism is not the negation of experience; rather, we must account for experience outside of its own terms . Binary oppositions, ideological schemas, and the like are useless without some explanation of what happens to us when we go to the movies.

The independent American cinema is a worthy object of study for such a criticism precisely because so much is left to the implicit (textually defined) viewer. A critique of the cinema of Bruce Baillie is impossible without a notion of how his films "work." Movies, to use Godard's formulation, are machines. You pay your money and take the effects. You like them or not. But we as viewers are part of the machine, and nowhere more so than in films such as To Parsifal . The machine exists through us, as well as through other factors—ideology first of all—beyond any immediate perception. But to understand it all, even to begin to understand what happens, we first must know what happens at the most basic levels—at our end of the machine.

Brakhage:

Artistic Development in Two Childbirth Films

William R. Barr

"Never trust the artist. Trust the tale," wrote D. H. Lawrence about uncovering significance in narrative fiction. Lawrence was protecting his work from his own remarks that, applied insensitively or maliciously, would distort meaning or even replace the texts themselves. His advice holds true as well for avant-garde film, especially when it seeks to reveal the workings of an artistic consciousness; with its relatively closely knit practitioners and small (but growing) number of followers, experimental film is dependent upon an oral tradition of communication and discussion. Stan Brakhage shares Lawrence's view of the autonomy of the individual work of art and the novelist's distrust of the artist as critic, declining any exceptional position he might otherwise claim by virtue of his acts of creation: "'Even when I lecture at showing of past Brakhage films I emphasize the fact that I am not artist except when involved in the creative process AND that I speak as viewer of my own . . . —I speak . . . as viewer of The Work (NOT of . . . but By-Way-of-Art), and I speak specifically to the point of What has been revealed to me AND, by way of describing the work-process, what I, as artist-viewer, understand of Revelation.'"[1] Granting the authority of the autonomous work of art, one can yet bring forth extra-artistic information which clarifies both the intention and the "work-process" behind and within the work; although one may not finally believe the teller one must listen carefully to him.

Understanding the context in which Brakhage operates is particularly important because of the extensive use he makes of his family in his films. For example, "Open Field," one of the Sexual Meditations , might appear to be simply a parody of the stereotyped experimental film which shows a young, nude girl running through a field in slow motion. But the information that the girl is Brakhage's daughter entering adolescence and that the film is in part the father's attempt to come to terms with her emerging sexuality and his own feelings towards her leads to a less sterile interpretation. "Open Field" becomes, through its depiction of the psychological processes that make the film-maker human, a universalized and even mythic dramatization of the powers of time.