4—

In their efforts to achieve their own authentic visualizations of sight, avant-garde filmmakers have severed the bonds between the cinematic

image and the perspectivist tradition. They have broken the rules of filmmaking and subverted the cinematic apparatus. A paradigmatic statement of the avant-garde's approach to filmmaking appears in Brakhage's Metaphors on Vision:

By deliberately spitting on the lens or wrecking its focal attention, one can achieve the early states of impressionism. One can make this prima donna heavy in performance of image movement by speeding up the motor, or one can break up movement, in a way that approaches a more direct inspiration of contemporary human eye perceptibility of movement, by slowing the motion while recording the image. One may hand hold the camera and inherit worlds of space. One may over- or under-expose the film. One may use the filters of the world, fog, downpours, unbalanced lights, neons with neurotic color temperatures, glass which was never designed for camera, or even glass which was but which can be used against specifications, or one may photograph an hour after sunrise or an hour before sunset, those marvelous taboo hours when the film labs will guarantee nothing, or one may go into the night with a specified daylight film or vice versa. One may become the supreme trickster, with hatfuls of all the rabbits listed above breeding madly.[37]

Such a "supreme trickster" is Brakhage himself, whose hats have produced "all of the rabbits listed above" and more. What is important is not the novel techniques per se but the recognition that these techniques are necessary to free the cinematic image from "Western compositional perspective" (Brakhage's expression) and the pictorial conventions it supports.

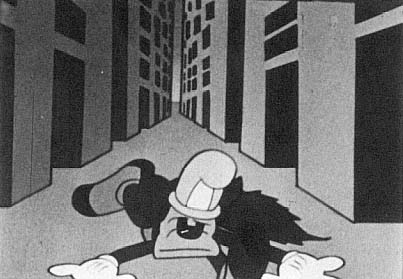

In a piece of found footage included in Brakhage's Murder Psalm (1980), a cartoon animal dressed as a policeman runs directly toward the audience, while the buildings lining the street recede behind him in exaggerated lines of perspective. Suddenly a car comes hurtling out of the vanishing point, runs over him, and disappears. With cartoon logic, the animal jumps up and continues running, now angrily waving his nightstick at the departed car. In subsequent shots he is run over again, and the last time we see him, he is lying flat on his face in the street. These are only a few brief images cut into a complex and subtly nuanced film, yet it is hard not to see in them a parable of the futility of trying to flee "Western compositional perspective" by running away from its vanishing point. Not only will it attack from behind, but it leaves its victim no option but to run straight ahead, toward the open end of the visual pyramid, which is, in fact, the flat, impenetrable screen. The screen, moreover, is only the base of another pyramid whose apex is (perceptually) in the viewer's eye and (optically) in the projector's gate.

Brakhage has long recognized the irony of campaigning against "Western compositional perspective" while continuing to work with its most

Exaggerated perspective in a found cartoon

(Murder Psalm , Stan Brakhage).

efficient tools. He has noted that the light between the project and the screen offers a striking equivalent to the visual pyramid intersecting the painter's picture plane. By its very nature, Brakhage has said, film emphasizes perspective and "creates this perfect tunnel" from the projector to the screen. But he also insists that this is an "artificial" situation and one that filmmakers can confront and expose by creatively using the medium against its own predilections.[38]

A good example is his own Song XII (c. 1966), which he has explained came about because of his extremely negative reaction to Chicago's O'Hare airport. Being in the airport had given him a terrible headache, and he decided that the cause had been O'Hare's long, glass-enclosed corridors, which made him feel trapped in a maze of vanishing points. Subconsciously his eyes had been fighting the strong pull of the corridors' lines of perspective and their dramatically emphasized vanishing points—effects made even more disturbing by the glass walls that superimposed and reflected them ad infinitum . As soon as he flew out of O'Hare his headache disappeared. Later he returned to make Song XII .[39]

His capsule description of the short 8mm film ("Verticals and shadows—reflections caught in glass traps") indicates some of the formal elements and general theme of Song XII , but it only hints at the film's confrontation with

"Reflections caught in glass traps"

(Song XII , Stan Brakhage).

the power of perspective.[40] The film is in gray and white, with almost continuous superimpositions that not only layer one image over another but soften shapes and wash out fine details as the shots overlap, dissolve, and fade in and out. Anonymous figures (or their reflections and shadows) appear briefly and usually in slow motion amid geometrically regular lines and planes (a visual pun on "plane" is even suggested by one shot in the film that actually shows an airplane beyond or reflected in a glass wall). The superimpositions produced by the reflections are compounded by the su-

perimposition of shots, and the viewer's eye becomes trapped by conflicting cues to perspective. It is not people in an airport but seeing itself that is "caught in glass traps."

The lens of Brakhage's camera is also a "glass trap," as Brakhage would be the first to admit. But that trap is sprung by the superimpositions, the overexposure, the cuts, fades, and dissolves with which Brakhage undercuts the single and immobile, precise, and authoritarian point of view built into the camera's lens. Instead of trying to run away from perspective within its own rigid lines (like the hapless cartoon policeman), Brakhage makes the lines and planes of perspective serve his own artistic (and in this case therapeutic) need to escape the tyranny of the vanishing point.

If Brakhage defeats perspective by changing its rules, Ernie Gehr beats it at its own game in Serene Velocity (1970). From a fixed point of view, like that of the artist's eye in illustrations of how to draw in perspective, Gehr's camera filmed a long bare corridor lit by a row of fluorescent lights in the ceiling. The lines formed by the floor, walls, ceiling, and lights converge toward a vanishing point behind two doors at the end of the corridor. The rectilinear space and dramatically receding lines make the basic image of Serene Velocity a model of geometrical perspective. It is a perfect cinematic equivalent of Alberti's formula: "A painting will be the intersection of a visual pyramid at a given distance, with a fixed center and certain position of lights, represented artistically with lines and colors on a given surface."[41]

In Serene Velocity , however, the "intersection of a visual pyramid at a given distance" changes every one-sixth of a second. The film alternates four-frame shots of the corridor taken at different focal lengths (with a zoom lens). As the film proceeds, the disparity between focal lengths gradually increases. 50mm shots are juxtaposed with 55mm shots, then 45mm shots with 60mm shots, 40mm with 65mm, 35mm with 70mm, and so on. Because of the principles of geometrical perspective built into the lens, each change in focal length is like a change in the place at which the imaginary picture plane intersects the visual pyramid. The (invisible) vanishing point at the center of the image remains the same because the camera position remains the same, but the angle of converging lines changes: narrowing as the focal length decreases, widening as the focal length increases. It is as if the vanishing point were leaping toward and away from the picture plane six times every second. The visual effect is to make the space seem deeper or shallower and the doors farther from or closer to the viewer, as the shots alternate between shorter and longer focal lengths. The increasing disparity of focal lengths produces a cinematic image that progresses from mild pulsations to what P. Adams

An empty corridor emphasizes the lines and planes of geometrical perspective

(Serene Velocity , Ernie Gehr).

Sitney describes as "an accordion-like slamming and stretching of the visual field."[42] The illusion of a stable three-dimensional space is thoroughly shattered by Gehr's manipulation of the very devices and conventions of geometrical perspective that were designed to produce it.

Michael Snow's Wavelength (1967) also exploits changes in perspectival relationships produced by changes in focal length. In Snow's film, however, the change of focal lengths (again with a zoom lens) only goes in one direction—from short to long, from wide angle to telephoto—so that an initial image of fairly deep space is slowly drained of its illusionistic depth. Like Gehr, Snow filmed a single enclosed space, a nearly empty room, from one point of view. But unlike Gehr, whose framing emphasizes the receding lines of perspective, Snow deemphasizes perspective by shooting from a high angle that centers attention on the far wall of the room, its windows, the tops of trucks passing outside, and the fronts of the buildings across the street. Although as Snow points out, "It's all planes, no perspectival space," the image retains a fairly strong impression of perspective (it could hardly do otherwise, given the optical properties of the lens) until the zoom-in has eliminated the cues to perspective and flattened the room's space against the wall and windows.[43] Then the image

can be seen for what it really is: light making "lines and colors on a given surface," in Alberti's phrase. In chapter 7 I will examine in much more detail the implications of Wavelength's zoom; for now, I simply add it to the list of ways avant-garde filmmakers have forced the lens to reveal what it is supposed to conceal: the problematic nature of perspective within the cinematic image.

Another way—brilliantly exploited by Sidney Peterson, most notably in Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur (1949) and The Lead Shoes (1949)—is the creation of anamorphic images. Anamorphosis was a direct spin-off of the development of Renaissance perspective and perhaps the first example of artists using the rules of perspective to frustrate ordinary seeing. (The best known example is an anamorphic death's head in the foreground of Holbein's The Ambassadors , but many other examples can be found in paintings since the fifteenth century.) As Claudio Guillén writes, "This vexing sort of visual trickery was but an extension of the illusionistic power implicit in perspective, and of the notion that the characteristics of vision could control the visible contents of the painting."[44]

In conventional perspective, the picture plane intersects the visual pyramid at an angle that is at, or fairly close to, a ninety-degree angle—like a window glass through which one views the scene outside. The anamorphic picture plane is either curved or skewed at an extremely oblique angle to the visual pyramid, which results in images that are weirdly stretched or squashed when looked at straight-on (as we look at most pictures) but will appear normal and in perspective if viewed from an oblique angle or reflected in a curved surface that matches the original point of view. The trick will work only if the artist rigorously maintains a fixed point of view and accurately reproduces the point-to-point correspondence between the three-dimensional objects and their two-dimensional images on the picture plane. An anamorphic lens applies the same mathematical rigor to bending light rays so that they strike the film at an "abnormal" angle and produce a cinematic image that looks distorted if it is projected through a normal lens but appears normal when projected through another anamorphic lens that corrects the original distortions.

Peterson's anamorphic images are intended to remain uncorrected, with the result that familiar shapes appear grotesquely elongated or unnaturally short and squat. They seem to occupy a space that is too shallow and strangely congealed (an impression encouraged by the extreme slow motion Peterson commonly uses in his films). These images may evoke "the realm of dream, memory or a visionary state," as Sitney suggests, but first and more overtly they subvert the objective visualization of sight

that the rules of perspective are presumed to guarantee.[45] Peterson himself has said that anamorphosis is "the most subjective of all the branches of linear perspective" and hence a way of emphasizing "the subjectivity of the viewing process."[46]

To wring a subjective visualization of sight out of the objective lens is what Brakhage had in mind when he recommended using the lens "against specifications." Another example of that tactic is Ed Emshwiller's practice of filming with a wide-angle lens brought very close to his subjects. As Emshwiller's camera moves over them, parts of the body balloon out then shrink away; all sense of proportion disappears; the solid, three-dimensional world becomes an undulating field of polymorphic shapes. Relativity (1966) is not only the title of Emshwiller's best-known film, it is also the principle underlying these visualizations of sight: there is no single, correct representation of objects in space; all is relative to the point of view and the way the lens bends the light rays.[47] Like Peterson's "subjectivity of the viewing process," Emshwiller's relativity of the cinematic image is as prized by avant-garde filmmakers as it is abhorred and hidden by the dominant film industry—except for occasional special effects, dream sequences, and the like. The avant-garde does not need such narrative excuses to justify its rejection of the lens's objectivity.

Avant-garde filmmakers have found many other ways to break the lens's subservience to the goals of geometric perspective. The murky, stippled image in parts of Man Ray's Etoile de mer (1928) and the multifaceted psychedelic images in passages of Kenneth Anger's Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969) and a number of other films of the 1960s were produced by special lenses. But many filmmakers have found that simply by throwing an ordinary lens out of focus—"wrecking its focal attention," as Brakhage calls it—the spatial clarity of perspective will dissolve into glowing colors and mysterious, overlapping shapes. Superimposition (another tactic favored by many avant-garde filmmakers) automatically destroys the single, fixed point of view essential to perspectivist representations of space. Collage techniques and masking can produce disproportionate sizes and conflicting vanishing points within the same image. Rapid camera movement can flatten space and shatter the edges separating objects from each other and the space around them; if it is rigorously pursued, it can evoke totally new perceptions of space—as has been demonstrated in films as different as Brakhage's Anticipation of the Night (1958) and Snow's « (Back and Forth ) (1969) and La Région Centrale (1971).

Rapid intercutting of simple images and movements also flattens the perceived space, as Léger seems to have been the first to discover while

making Ballet mécanique (1924).[48] If the intercutting is rapid enough and extended over a long enough period of time, as in Tony Conrad's The Flicker (1966) and passages of Paul Sharits's "flicker films," the flatness of the screen can give way to illusory and ambiguous perceptions of depth that have nothing to do with the depth cues of perspective. In a very different way, Duchamp's Anemic cinéma (1927) turns depth perception into an optical illusion by presenting rotating spirals that seem to protrude from and recede into the screen itself.

Jordan Belson exploits a similar illusion in Allures (1961), though in most of his films the methods are much subtler and involve coordinates and cues to perspective that are constantly changing the implied point of view of the camera. The result is a "disembodied perspective," which Sitney associates with a passage in Olaf Stapledon's science-fiction novel Star Maker: "But I had neither eyes or eyelids. I was a disembodied, wandering viewpoint."[49] Similar effects can arise from contemplating the permutations of vastly intricate dot patterns in James Whitney's Yantra (1957) and Lapis (1966).

There are also avant-garde films with images that have never been subjected to the perspectival biases of the lens because they were made without cameras—such as the "Rayograms" opening Emak Bakia (1926), the scratched and painted films of Len Lye, Norman McLaren, Harry Smith, and Stan Brakhage, to mention a few of the best-known practitioners of these handmade effects. There is also that tour de force of cameraless films, Brakhage's Mothlight (1963), with its bits of leaves, grass, flowers, and moth wings taped to the surface of a clear film base.

Some of the films mentioned above will be examined more fully in later chapters. Comparable examples could be listed almost endlessly if more evidence were needed to demonstrate the avant-garde's concerted effort to challenge the perspectivist tradition and break its hold on the manufacture and conventional uses of the cinematic apparatus. Virtually all avant-garde filmmakers have contributed to and profited from this effort to make the cinematic image a fuller and much more revealing visualization of sight—no one more so than Stan Brakhage, whose campaign on behalf of what he calls the "untutored eye" has produced the most pointed attacks on and most creative departures from the conventional cinematic image. To appreciate the nature of that campaign, we must make an excursion into the history of theories of visual perception—where we will discover significant corollaries to the propositions concerning vision, perspective, and the cinematic image that we have examined in this chapter.