Calmallí:

The Social Nexus

Los Marquez, los Smith, and los Castellanos arrived in Calmallí as experienced miners. They came knowing the jobs, the life-style, and many of the people supporting themselves on the mining circuit. The underlying base of all social interaction between kin and nonkin was, of course, the mining economy, which had pulled the various families together into a specific community. The permanence of these people in Calmallí led to full, meaningful social ties that later afforded a social base from which friendships and ties became paramount factors in adaptation in the U.S. These families created social environments that revolved around the work and life-style of Calmallí (and other mining sites). The long production of Calmallí provided the economic security that allowed continuous contacts between mining families who were now a permanent part of the mining economy. The mining economy was the landscape of their social environment and the basis for a life-style that became permanent in family lore. The pioneers of this study identified with the mines, with the technology of the time, and associated all of this with the social relations that evolved during this period.

Don Loreto Marquez

Don Loreto met the Smith, Castellanos, Bolume, Alvarez, and other core families in Calmallí. He remembers them as vividly as he remem-

bers the work and its technology. The work played a great role in family relations and in the quality of life in Calmallí. Don Loreto's recollections illustrate the spirit of life in Calmallí, the miners' perspective on company labor, and the pride they took in their work.

The first time we were there plenty of time. There were lots of people and plenty of gold there at that time. The company from San Francisco set up a very large mill in Calmallí. They spent many thousands of pesos there. Well, the mines paid out. Three or four mines that were worked silver, the crushing of the ore and throwing in quick silver. And there in the quicksilver they got the gold. (2/18/76:5)

The mining mill was pretty far back. I believe about two or three miles. There was a wagon road, just for mule wagons. From up there, where the people were in the mines, the company carried out the ore. With machinery, I'm telling you, with "donkeys," as the machines were called. The machines pulled and there were some huge braces. The ore was taken out and dumped into some very large chutes, and from those chutes the wagons were filled. The filled wagons were then taken to the mill.

I worked in the mill. First, I worked in the furnace where wood was used. It was a hell of a job; steam was raised to move the machinery. The work of the mill . . . nothing else. Most people have no idea . . . it's a very specific type of work, beautiful work and very costly. Because there is a lot to be done. No, not just taking the pure ore and letting water run. No!

Here in front . . . is a type of chute where the ore falls. A piece of steel from the actual millstamp strikes and turns a small wheel as the ore is already falling inside where the stamp is striking. You see? But if too much falls—there can't be too much at the same time—the stamp doesn't rise and it doesn't work well. Because that's the way the stamp's stroke is. Each stroke is five inches, just this much, of height. It lifts only this much . . . five . . . and it drops and drops. The five stamps drop like this, almost at the same time.

Along with his pride in the mining way of life, Don Loreto demonstrated an awareness of the situation in which he and other mining families found themselves. They were company miners and had come

to the mines looking for security in employment and in the social relations common to the towns of Baja California. Calmallí, like other mining towns, also attracted gold seekers and fortune hunters who flocked to the larger strikes and roamed the nearby crevices and dead streams in their attempts to strike it rich. Don Loreto talks about this contrast between company labor and independent prospecting.

There in Calmallí . . . many people worked in the mines. But for salary, understand? There were lots of people who moved over here, over there, in the small ravines searching for a little gold with small contraptions that they made themselves.

A lot of people did that and that's how they earned a living. Many took out gold. They were lucky, they extracted little nuggets of one adarme [one sixteenth of an ounce]. As many as two, three adarme . The little gold nuggets. But not others. It was very fine gold. They had to use quicksilver.

He also remarks on the richness of the strikes: "Over where the mill was breaking the rocks, the company was extracting the gold. It was very rich, very rich. Many people succeeded [in getting some gold]. Those who were not foolish. We were very foolish because we didn't succeed. We weren't smart enough to grab even just a small amount" (2/18/75).

Don Loreto described his meeting with the Castellanos.

R. Alvarez: It was there then, that you met Narcisso Castellanos?

Don Loreto: Yes, in Calmallí.

R. Alvarez: Were they already there?

Don Loreto: I can't say for sure if they were there already. But that is where I met them. I was still very young at that time. Well, you know, when you're young you don't notice people too much. Yea . . . and we worked the mines there. Castellanos, the senior, Narcisso, he was the mayordomo of the mines, of the mine laborers who worked right inside the mines. About fifteen or twenty men worked inside, you see? He was the boss and gave orders there. He was called "capataz " there. (3/8/76:4)

Narcisso Castellanos continually helped Don Loreto in the mines and later provided support when Loreto first arrived in San Diego. In addi-

tion, los Marquez and los Castellanos became formally tied through multiple compadrazgo relations in the north.

In Calmallí Don Loreto also met Ursino Alvarez (my paternal grandfather), another compadre, who worked directly under Narcisso Castellanos in the mines. Don Loreto mentions the company "neighborhoods" that brought them together.

Ursino? I met him down there in Calmallí. In the placers of Calmallí, that's where I met him. He worked in the mine . . . the Castellanos family was there too, my father, everybody. There was plenty of work in the mines when I met him there. Well, I would see him but I was very young and I didn't know much, like when one is older. But there he was. He always came to the house, to talk, like all the working people. People met at night to talk there in the houses. That is when I met him. Later when all the Castellanos came here to San Diego, he came too . . . following his girlfriend. [Ursino wed Ramona Castellanos in San Diego.]

Families shared work and social experiences and developed the trust that became a basis for reciprocity along the mining circuit to the north as well as later in the frontera. Don Loreto met los Bolume in Calmallí. A Bolume daughter, Guadalupe, married Jesus Castellanos, and they became compadres in San Diego. The Simpsons were also in Calmallí in the late 1880s, and Don Loreto's sister (while on the mining circuit) married into another Calmallí family, los Lopez, who had also arrived from the southern cape. Los Smith and los Marquez also became close acquaintances in Calmallí. Don Loreto clearly expresses the friendship between the families.

We met Apolonia there. That's where we came together. When I went to work I passed about twenty feet from the door of her house, to the job I was working in those times. Manuel was there. Adalberto. Adalberto was about ten or twelve years old, less, I believe. He went around with Manuel, because Manuel had burros to haul firewood to the work there. He went to the mountains, he cut firewood and . . . he took it to the company and they paid him . . . by the cord. They made their living from it.

Los Smith

The history of the Smiths on the mining circuit illustrates the formation of friendships and close ties with nonkin as well as the maintenance of home kin ties. Although other families also maintained such ties, evidence of this communication is not seen until they are in the northern section (e.g., the Castellanos received Gaxiolas and Villavicencios in San Diego during the 1920s). Los Smith, however, left Comondú with immediate kin, were received in Calmallí by kin, and aided and received kin throughout their residence there.

In Calmallí[8] the Smiths were no longer the inexperienced pueblo dwellers that had come to seek work in the mines. Manuel came as a leñador, a job specific to the mines which he had practiced in Las Flores. The necessity of fuel for the boilers in the mines as well as for horne cooking created the small economy by which Manuel and a host of other independents became tied to the mines. Where there were mines, there was work for Manuel. Los Smith arrived in Calmallí along with their two children, Adalberto and Francisca (who had been born in Las Flores). In Calmallí a third child, María, was born.

Along with immediate family and friends like Loreto Marquez, los Smith had close kin in Calmallí. Manuel's sister Ramona was in Calmallí with her husband, Charlie Howard, an American who was working the placers of Calmallí. María, although quite young at this time, recalls visiting her Tía Ramona with whom, she says, her parents spent much time. When Ramona died in Calmallí, of complications at the birth of twins, both Manuel and Apolonia were with her. Charlie Howard left Calmallí with the twins and was never heard from by the family again.

In Calmallí the Smiths kept close ties with kin in Comondú. Letters to Apolonia's parents and sisters kept home kin in continual communication with los Smith. During Apolonia's pregnancy with María, her mother became ill and died (c. 1901). Martina and Antonia, Apolonia's sisters, knew she was in the last months of her pregnancy and wrote Manuel of the seriousness of Apolonia's mother's condition. They informed Manuel but asked that the news be kept from Apolonia, fearing for her health and the child's. This constant communication kept all kin informed about their relatives. It also facilitated the reception of kin who were on their way north as well as kin who would come north later in the century. The Mesas, for example, were received by Apolonia and Manuel Smith in Calmallí.

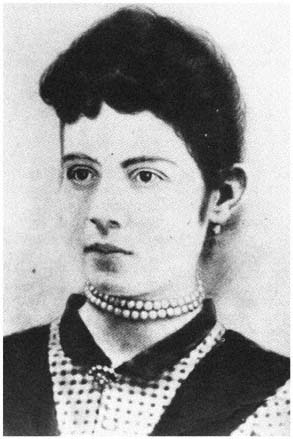

Ramona Smith de Howard (c. 1890), sister of Manuel

Smith, married Charlie Howard, an American working on

the mining circuit. She died in Calmallí, from complications

at the birth of twins, who were taken to the United States

and never heard from again.

(Courtesy of Ernestina Ignacia Mendoza Allen)

The Mesa family migration north illustrates not only the Smiths' hometown kin ties but also the nature and the significance of kin ties in family migrations from hometowns into the central and northern peninsula. Salvador and Juana (Apolonia's paternal aunt) Mesa left Comondú, according to (their daughter) Paula, because their eldest

son had left for the north and their mother wanted to be close to him. In Comondú Salvador had packed grapes and figs destined for Santa Rosalía. From Comondú Salvador and Juana traveled to San Ignacio with six children and stayed in that mission town, where Salvador managed fruit fields (administraba las huertas ). Although successful there, the family left San Ignacio to follow kin who had gone further north. They left in October and traveled through the central desert to the northern boundary town of El Rosario, arriving on December 3, el Día de San Francisco . On their way they passed through the mining towns of Calmallí and Julio César. In Calmallí Apolonia and Manuel Smith received Salvador, Juana, and the children. They stayed several days, resting, visiting, and exchanging news with Apolonia. Juana and Apolonia had been close friends and Juana was continually thinking and asking about Apolonia (so reports Hirginia, Juana's daughter). Los Mesa moved on to the north, arriving in San Quintín, where they later received los Smith when Calmallí ended production.

Among the important network relations of los Smith in Calmallí were friendships formed with nonkin. Friendships established at this time with los Bolume, los Marquez, los Simpson, and others were to have significant meaning in later years. An informal network of social relations between los Smith and los Castellanos later developed into kin ties through marriage and compadrazgo . A good example of one such link is Guadalupe Bolume, a close friend of Apolonia's during the years on the mining circuit. Guadalupe was born in Calmallí and later became comadre to the Mesa-Smiths as well as to los Marquez, and she married into the Castellanos family. This cluster of families—los Smith, los Castellanos, los Marquez, los Simpson, and los Bolume—was identified by a close friend of them all, Señor Villavicencio, who now lives in Pozo Alemán. He recalls their long stay in Calmallí and their relations as a group.[9]

Los Castellanos

Narcisso and Cleofas Castellanos were among the earliest of arrivals to Calmallí, and they spent a great deal of time in that town. When Narcisso entered the mining circuit, Ramona was an only child. By the time the family left Calmallí, six more children had been born and three others would be born in more northerly mining towns. For the Castellanos Calmallí was truly a nexus, the landscape in which specific social

ties formed a basis for future marriages, compadrazgos, offspring, and future generations.

La familia Castellanos consisted of Narcisso, Cleofas, Ramona, Jesus, Juana, Espiridiona, Francisca, and Abel. Like other core families

Diagram 5.

Los Castellanos when they left Calmallí

in Calmallí, los Castellanos did not actually marry during this period, but the bases for later marriages and compadrazgo relations were laid in Calmallí. Of the Castellanos children who grew up and were socialized in Calmallí, all of these married into Baja California families. But three married into core families. Courtships for some of these marriages began in Calmallí, as is illustrated by Don Loreto Marquez: "It was in Calmallí where I met him [Ursino Alvarez]. Later when all the Castellanos came here, he came too . . . following his girlfriend. My comadre Ramona worked [in San Diego], I'm not sure for whom. But she wasn't married yet. She was being courted by Ursino."

Other similar courting relations developed in Calmallí and in other mining circuit towns. Guadalupe Bolume recalled dancing with Vicente Becerra, who played guitar at social affairs in the mining towns and who played for her wedding decades later in San Diego. Vicente himself was married in San Diego to Guadalupe Gonzales, who had also been on the mining trail with her parents.

Numerous marriages and compadrazgo relationships based on mining friendships occurred later in San Diego. Offspring of these marriages then intermarried and further reinforced the solidarity of these families in the frontera region. Overlapping formal compadrazgos also united families. Don Loreto, recalling Jesus Castellanos, stated, "Jesus married my comadre Lupe [Bolume]. Jesus, the brother of my comadre Ramona."

The Calmallí period, for Narcisso and Cleofas Castellanos, was not a brief interlude or simply part of a migration north. They, like the

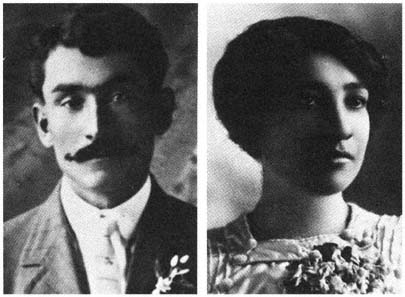

Ramona Castellanos and Ursino Alvarez, San Diego. c. 1915

majority of others, saw themselves as permanent settlers in Calmallí. But when the mines fluctuated, they were forced to seek jobs and homes elsewhere. In many ways these individuals were locked into the mines. Narcisso, as capataz of barreteros had developed a skill specific to the mining economy, and he built his life and his family's life around that security. His children were born and raised in this environment, as were the children of the Sotelos, the Bolumes, the Smiths, the Simpsons. When the Calmallí mine could no longer support the families of workers, people moved on. Many were encouraged to head north because El Marmol, Julio César, and other small mines were producing and employing mine laborers.