The War Years, The Postwar Years

The lingering effects of a 1939 auto accident, in which Burton Cairns was killed, kept Eckbo from active military service.[72] And a few weeks' work in a Sausalito shipyard convinced Eckbo that his talent lay in design; he went to work for the war effort, planning four dozen schemes within a three-year period. The site and landscape development for the community and commercial center in Vallejo, designed by Theodore Bernardi and Ernest Kump, paralleled designs by Thomas Church for housing by William Wurster on other parts of the site. The means were meager; the allotted time, virtually none. Once again, sinuous lines of poplars doubled as spatial integrators and windbreaks, softening the relentless march of standardized units that followed the contours of the grassy hillsides.

With hostilities ended in August 1945, America began the return to normalcy. Given the transplanted minions of workers who elected to remain in the Golden State, the GI Bill that gave veterans access to education and homes, and the basic optimism that accompanied the nonmartial economy, California boomed. Suburbs developed on the perimeter of every major city in the state, soon to be rendered the inside of the city and not its edge.[73] Freeways provided access to greater and greater amounts of land gobbled by suburban development, calling for more freeways and even greater development. The cycle never abated.

Eckbo formed a partnership with his brother-in-law, Edward Williams, in 1940 and designed a number of gardens in the San Francisco Bay Area while employed with the FSA and war housing programs.[74] At a Telesis gathering before the war, Eckbo met Robert Royston, who worked for Thomas Church from the late 1930s until he entered military service. Royston, always known as an extremely talented designer, became a mainstay of the Church office and supervised the defense workers' housing project in Vallejo. By mail, Eckbo invited him to join the firm as partner upon his release from the Navy, where he was serving in the Pacific theater. Royston had come within a hairsbreadth of partnership with Church: "When I got home Tommy had my name on the door. It was a difficult period for me

because I liked Tommy very much and we had a close relationship. But Garrett always attracted me because he's a clear and social thinker, and he can really see the whole picture." He described practice as a brand-new world where "we could experiment right and left."[75]

Eckbo, Royston and Williams was established in 1945, and within five years it had become one of the leading firms in the country, highly regarded for its advanced planning ideas, innovative modern vocabulary, and its quality of execution. It was during these years that the distinctive Eckbo idiom developed, prompted by the association with Robert Royston, and in collaboration with leading architects such as Joseph Stein, John Funk, and John Dinwiddie. To some degree, these designs developed ideas first proposed in the Small Gardens and Contempoville studies, but each of these ideas was tempered by the particular conditions of the site and program.

The 1939 garden for Mr. and Mrs. F. M. Fisk in Atherton had allowed Eckbo to work at larger residential scale, pairing sunny lawn and "natural meadow" areas with layered spaces defined by hedges, set under oaks and redwoods [figures 29, 30]. The net effect was one of openness and enclosure, sun and shade, boundary and vista. That no aspect of the garden was perceived as absolute is also suggested in a pencil study for the Reid garden in Palo Alto from the same period [figure 31]. The low hedges established an orthogonal structure in which the house reverberated in the garden; but the overarching frame of trees led the eye over and beyond these spatial dividers toward the horizon. For John Dinwiddie's 1941 Frazier Cole house in Oakland, Eckbo used curving planes of wooden screen walls to enclose fluid spaces around the house, protecting them from unwanted street noise and outside view [figures 32, 33].

As a group, the designs for northern California gardens of the period following immediately after the war could best be characterized as considerate of their clients' needs and the dicta of the site, and intelligent in deriving forms to suite those requirements. Although touches of modernity appear in their spatial definition, in the curving of a wall or in the use of some offbeat paving material, the gardens

29

Fisk garden. Site plan. Atherton, 1939. Photostat.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

30

Fisk garden. View southwest over the lawn area. Atherton, 1939.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

31

Reid garden, Study. Palo Alto, circa 1940. Photostat.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

32

Cole garden. Axonometric view. Oakland, 1941. Photostat.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

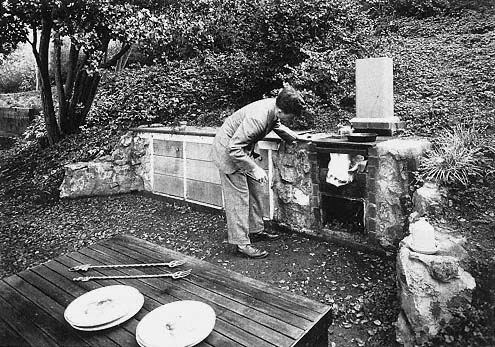

33

Cole garden. Retaining wall with built-in barbecue—and Garrett Eckbo. Oakland, 1941.

Photostat. [Philip Fein, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

34

Robert Royston. Platt garden.

Axonometric view. Oakland, circa 1946.

[ from Architect and Engineer]

35

Robert Royston. The Palo Alto. Pool area. Palo Alto, 1950s.

[Louis Alley, courtesy Robert Royston ]

remained polite and restrained, lacking the full-blown exuberance of the following years in southern California.

Each partner ran his own projects, and interests and formal vocabularies varied to some degree from their common sensibility. A profile of the year-old firm, "A Professional Adventure in Use of Outdoor Space," appeared in the September 1946 issue of Architect and Engineer . It not only illustrated the gathering esteem with which Eckbo, Royston and Williams' production was held by the professional community, but also the qualities the partners held in common:

Their principle of work is: Work—They like their work and like to work . Provide the best possible service—They believe in thoroughness, attention to detail, and recognize that quantity without quality is nothing . Get recognition for good work—They don't believe in hiding their light under a bushel. They feel very seriously that unless they produce the best quality work that they will not have a place in the profession.[76]

Eckbo and Royston appear to have been the stronger landscape designers; Williams gravitated toward projects of larger scale, such as recreation and community planning. At this time, Royston's garden designs tended to favor a vivid play of curved and angular planes defining the "open center," usually a lawn or paved patio. The garden or park's central space predominated, supported by secondary areas formed with fences, hedges, and trees [figures 34, 35].

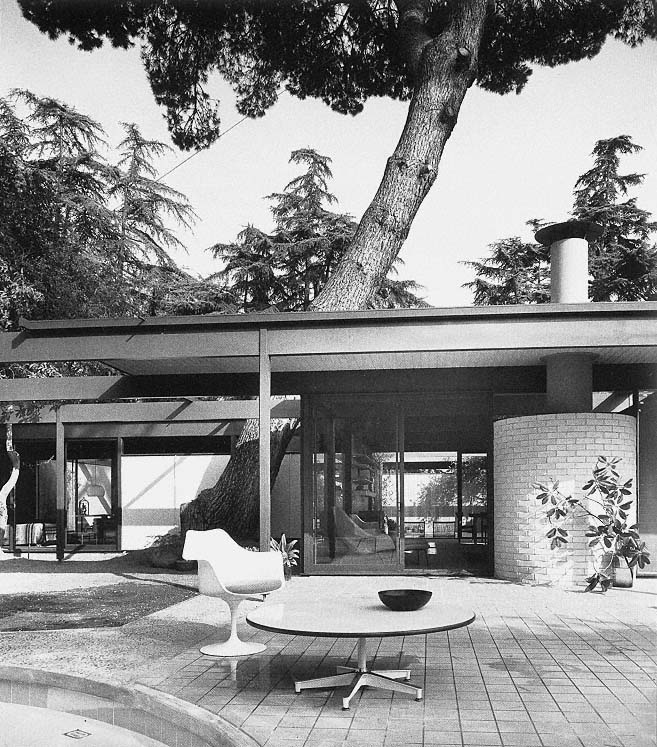

For landscape architects, the housing boom provided almost unlimited opportunities, especially in the Southland. The evolving California pattern of indoor-outdoor living required designed exterior space to complement interior subdivisions. The Case Study House program, sponsored by Arts and Architecture magazine between 1948 and 1962, realized demonstration projects that included gardens as a vital part of the design. Eckbo's landscape designs accompanied projects by Rodney Walker in Beverly Hills from 1947 and Conrad Buff, Calvin Straub, and Donald Hensman's 1958 Case Study House #20 in Altadena. These designs for display were necessarily less assertive than gardens designed for specific clients but they provided the perfect accompaniments—and counterpoints—to the architecture of their respective houses [figure 36].[77]

36

Case Study House #20. Pool area with Italian stone pine. Altadena, 1958.

Buff, Straub and Hensman, architects.

[Julius Shulman, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]