One—

Ram's[*] Story in Shiva's City:

Public Arenas and Private Patronage

Philip Lutgendorf

Infinite is the Lord, endless his story.

All good people in diverse ways tell and listen to it.

The captivating deeds of Ramchandra

Cannot be sung even in ten million aeons!

RAMCHARITMANAS[*] , 1.140.5,6

The Performance

The setting is a mandap[*] , a brightly canopied enclosure for festive observances, erected in a small square in the heart of Banaras (see fig. 2). The ground within is spread with cotton rugs on which hundreds of people are seated, men and women on opposite sides of a central aisle. At the far end of the enclosure stands a lofty dais draped with rich brocades, on which an oversized book, covered with flowers, is enshrined on an ornate stand. A dignified looking man, immaculately clad in a crisply pleated dhoti and silk kurta[*] , reverences and then mounts the dais, whereupon he is garlanded by another man. Closing his eyes, he composes himself in a brief meditation and then begins murmuring an invocation. He salutes Shiva, primal guru of the world and special patron of this city, Valmiki, the first singer of Ram's deeds, and Tulsidas, who brought the divine song into the language of ordinary people; he also venerates his own teacher, and Hanuman, the beneficent patron of all retellers of the Ramayan[*] . Finally he opens his eyes and begins to chant: "Sita-Ram, Hail Sita-Ram!" The crowd takes it up after him, beginning many rounds of antiphonal exchange, until the speaker senses that the proper atmosphere of devotion has been created. Then at last he begins to speak, reciting from the book that lies before him, though he never opens its petal-strewn cover. The listeners know that he has no need to read from this book, for he has studied it so deeply and internalized it so completely that he has it, as they say, "in the throat"[1] —he has himself become its living voice. Now he invites his listeners to enter the special world of this book, an entry that may be made at any point, since the whole story is a divine revelation charged with the pro-

[1] Kanthastha[*] , the Hindi idiom for "memorized."

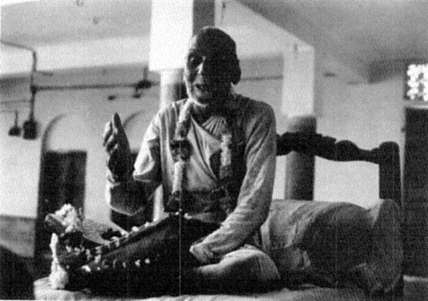

Fig. 2

The podium and a section of the crowd at the Manas-katha[*] festival held annually

at Gyan[*] Vapi[*] (November 1982). Photograph by Philip Lutgendorf.

foundest significance. Selecting a single line, the speaker begins to muse and expand upon it; to "play" with it as a classical Indian musician might play upon a raga. But here the improvisations consist not of musical tones but of words and ideas, images and anecdotes, folk sayings, scriptural injunctions, and snatches of song from great devotional poets, all interspersed with numerous chanted quotations from the book itself. The speaker has no single theme, constructs no systematic argument; instead he evokes a succession of moods and invites his audience to savor them. His purpose is less to analyze than to celebrate, and when a fresh insight occurs to him he "digresses" to explore it.

As he performs he engages his audience in numerous ways: making a particularly striking point, he turns to certain listeners near the front of the crowd to solicit their approval and is rewarded by exclamations of delight; chanting a well-known verse from the book, he stops midway and motions for listeners to supply the last few words, evoking a rhythmic and enthusiastic response. A particularly poignant anecdote brings tears to many eyes, but these give way in the next moment to hearty laughter over an earthy recasting of the story and its divine characters. Narrating dialogue, the speaker assumes the various parts and acts them expertly, with vivid facial expressions and gestures.

The speaker's verbal tapestry envelopes the crowd for nearly an

hour, and then with expert timing he ends it with a resounding benediction: "Hail Sita's bridegroom, Ramchandra!" just as a priest appears before the dais bearing a brass lamp, which he waves in worship before the book. The listeners rise to sing a hymn in its praise, and when this concludes many come forward to place an offering on the book, to touch the speaker's feet reverently, and to receive from him a blessing of prasad[*] in the form of sacred tulsi[*] leaves from a sprig that has been resting on the book.

Performances resembling the one just described have been an important part of life in Banaras for many centuries. They are hardly unique to that city, of course, for similar forms of oral exegesis, perhaps differing in certain details or based on other texts, are found throughout much of India.[2] But Banaras has a special connection with the "book" in the present example, the Hindi epic Ramcharitmanas[*] —commonly called the Manas[*] , or simply the Ramayan[*] (since most Hindi speakers have no direct knowledge of the older Sanskrit work by this name) and generally acknowledged as the most popular text of north Indian Hinduism—for it was in this city that Gosvami Tulsidas (1532–1623) was said to have completed his epic and to have personally initiated its public performance through katha[*] (oral exegesis) and lila[*] (dramatic enactment).[3] During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the religious and political elite of Banaras enthusiastically cultivated these traditions, establishing patterns of Manas patronage and performance that were emulated in other areas of northern India. While the annual cycle of Ramlila[*] plays has been the subject of a number of studies, the rhetorical art of katha , which occurs throughout the year, has received little scholarly notice, perhaps in part because its performances are less conventionally "theatrical." Yet such programs are held in virtually every neighborhood of Banaras, and a number of largescale ones have in recent years become important events for the whole city. This chapter will outline the development of this performance tradition, giving particular emphasis to the cultural and political context of its patronage.

Origins of the Tradition

While the term katha is often understood to mean simply "a story," this translation tends to overly nominalize a word that retains a strong sense

[2] That is, the harikatha[*] of Maharashtra and Karnataka, the burrakatha[ *] of Andhra, and the kathakalakshepam[*] and pirachankam of Tamil Nadu. Most of these genres have been little studied. On Harikatha[*] , see Damle 1960:63–107.

[3] All quotations from the Ramcharitmanas refer to the popular Gita Press version edited by Poddar (1938); numbers indicate kand[*] ("canto"), doha[*] ("couplet"), and individual line in the "stanza" preceding the doha .

of its verb root. In India a "story" is, first and foremost, something that is told , and the Sanskrit root kath , from which the noun is derived, means "to converse with, tell, relate, narrate, speak about, explain" (Monier-Williams 1899:247). Katha[*] might thus better be translated a "telling" or "narration"; it signifies a performance and suggests a milieu. To tell a story means that there must necessarily be someone to hear it, and in Hindu performance traditions the role of the "hearer" (shrota[*] ) is generally a participatory rather than a passive one.

The roots of katha[*] -style performance lie in ancient Brahminical traditions of teacher-disciple dialectic and oral exposition upon existing sacred text; a milieu that can be glimpsed, for example, in the teaching dialogues of the Upanishads and in the terse structure of the sutra, which often presupposes the presence of a living expounder. The development of storytelling as a form of mass entertainment, however, was first reflected in the Sanskrit epics, the traditional narrator of which was the Suta[*] , originally a charioteer and royal herald (Rocher 1985:2.1.2). While the Suta's social status appears to have been relatively low, at least in the eyes of Brahmin legalists, the "tales of wonder" with which he entertained priests and kings during breaks in sacrificial cycles came in time to be seen as powerful religious narratives, which could even claim a sanctity on a par with that of the Vedas themselves. Significantly the Mahabharata[*] provides evidence of the growing involvement of Brahmins with the epic, as its memorizers, performers, and elucidators (e.g., Mahabharata 1.1.50).

The role of the oral mediator of sacred text increased in importance with the emergence of devotional cults advocating the worship of Vishnu[*] and Shiva and offering hope of salvation to faithful devotees regardless of sex or social status. The message of this new religious movement was set in the form of the "old story" (Purana), and while its language was still the Sanskrit of the twice-born elite, its intended audience explicitly included the lower classes, women, and Shudras.[4] To reach this largely illiterate audience, the Puranas ceaselessly advertised the merits of their own recitation and exposition, and even offered detailed directions for the staging of such performances (Bonazzoli 1983:254–80). The performer was called by a variety of names: pauranika[*] (puranic specialist), puranajna[*] ("knower" of the Puranas), vyakhyatri[*] (expounder), and vyas[*] . The latter term, denoting one who "separates" or "divides," recalls the archetypal expounder Veda-Vyas, who "divided" the one Veda into four in order to make it more readily comprehensible to the men of this Dark Age, and who was also credited with the authorship of the Mahabharata and of many of the

[4] An explicit statement to this effect is found, for example, in the mahatmya[*] of the Bhagavata[*]Purana[*] ; Shrimad[*]BhagavataMahapurana[*] 1964, 1:36.

Puranas themselves.[5] The puranic vyas[*] was viewed as a spiritual descendant or even temporary incarnation of Veda-Vyas (himself an avatar of Vishnu[*] ) and was privileged to speak from a vyas-pith[*] : a "seat" of honor and authority in the assembly of devotees.

This assembly too had a special designation: satsang or sant-samaj[*] —"fellowship with the good." Although such congregational expression of religious feeling must have become common quite early in the puranic period, the establishment of Muslim hegemony in northern India in the late twelfth century helped create conditions favorable to the spread of this tradition. Unlike the Vaishnava royal cults of an earlier period, devotional expression through satsang required no elaborate superstructure of temples and images that could become targets for the iconoclasm of the new rulers, and storytellers and expounders were often wandering mendicants whose activities were difficult to regulate. Moreover, the bhakti message of devotional egalitarianism made a strong appeal to those of low status and served to counter the social appeal of Islam; this factor may have encouraged the patronage of wealthy twice-born Hindus who were alarmed at the conversion of lowcaste and untouchable groups.[6] A related development was the composition of new "scriptures" in regional languages, in order to carry a devotional message—and any appended social messages—to the widest possible audience, regardless of whether it had access to the Sanskritic education of the religious elite.

The importance of oral exposition of scripture during the sixteenth century is amply attested by the Manas[*] itself, for Tulsidas's epic, set as a series of dialogues between gods, sages, and immortal devotees, invariably characterizes itself as a katha[*] , "born, like Lakshmi, from the ocean of the saints' assembly" (Ramcharitmanas[*] 1.31.10), and it constantly admonishes its audience to "sing," "narrate," and "reverently listen to" its verses.[7] The hagiographic tradition depicts Tulsidas himself as a kathavachak[*] ("teller" of katha ), and the poet's frequent references to himself as a "singer" of Ram's[*] praises seem to accord well with the traditional image. It is noteworthy, however, that while the Manas appears to have rapidly acquired a singular and far-flung reputation among

[5] The link between "division" and creative "elaboration" becomes clearer if we recall that, in Hindu cosmogonic myths, the act of creation is often accomplished by means of a primordial separation or division. See, for example, Rig Veda 10.90, Brihadaranyaka[*] 1.2.3, and Manu 1.12,13.

[6] Damle makes this argument with reference to the Maharashtrian harikatha[*] tradition, which he feels became systematized during the period of Muslim rule (Damle 1960:64).

[7] Such admonitions occur particularly in the phal-shruti verses at the end of each kand[*] ; for example, 3.46a; 5.60; 7.129.5,6.

Vaishnava devotees[8] and among sadhus of the Ramanandi[*] order, it does not seem to have initially won the allegiance of the religious and political elite of Banaras. Although the legends of the epic's miraculous triumph over Brahminical opposition may lack historical veracity,[9] the process which they implicitly suggest was undoubtedly a real one: the slow and grudging acceptance by the religious elite of an epic composed in "rustic speech" and cherished by the uneducated classes and by the casteless mendicants of what was, at the time, one of the most heterodox of religious orders (Burghart 1978:124).

The Rise of Elite Patronage

The historical developments that were to lead to present-day styles of Manas[*] performance can be most clearly traced from the eighteenth century onward. The great political event of that period in northern India was the collapse of Mughal hegemony over much of the region. The rapid erosion of centralized authority which followed the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 facilitated the rise, especially in the eastern and southern Ganges valley, of a number of regional kingdoms, some of which were again under Hindu rulers.

In 1740, when Balwant Singh, the son of an ambitious local tax-farmer, assumed the title Raja of Banaras, he did so as a client of the Nawab of Awadh, who was still the paramount political power in the region, and who in turn still displayed a nominal allegiance to the weak Mughal regime at Delhi. As Bernard Cohn has pointed out, the Banaras ruler was essentially a "middle man" within a complex system in which authority was parceled out at many levels and in which the division of power was constantly being renegotiated.

The Raja's obligations to the Nawabs were the regular payment of revenue and provision of troops when requested. The Raja of Banaras at every opportunity tried to avoid fulfillment of these obligations; and on several occasions the Nawab sent troops to try to bring his subordinate to terms, if not to capture and kill him. On these occasions, Balwant Singh would retreat with his treasure and army to the jungles of Mirzapur. After a time the Nawab, distracted by similar behavior in other parts of his

[8] Thus in Nabhadas's hagiographic classic, Bhaktamal[*] , thought to have been composed in Rajasthan in the late 1500s, Tulsi is already acclaimed as a reincarnation of Valmiki (Rupkala 1909:756, chhappay 129).

[9] The best-known story, which occurs in the controversial Mul[*]qosai[*]charit attributed to Benimadhavdas (1630?), recounts the "trial" of the Manas in the inner sanctum of the Vishvanath temple; placed on the bottom of a pile of Sanskrit scriptures when the temple is locked for the night, it is found in the morning to be at the top of the pile, with the words satyam, shivam, sundaram ("truth, auspiciousness, beauty") inscribed on its cover.

state or by his intervention in imperial politics, would compromise with Balwant Singh and withdraw, at which time Balwant Singh would resume his control of the zamindari. . . . A balancing of relative weakness appears to have been central to the functioning of the system. The Nawab could not afford the complete chaos which would result from the crushing of the Raja. (Cohn 1962:315)

If the Nawab was dependent upon the Raja because no one else was capable of guaranteeing the collection of revenue in the region (even if relatively little of it actually reached the Nawab's treasury), the Raja was in a similar relationship of dependency upon and intermittent conflict with his subordinates: numerous petty rajas, jagirdars, and talukdars who likewise controlled revenue and troops and were the primary intermediaries between the Raja and the peasants (Cohn 1962:316–17).

That the Nawab of Awadh was Muslim and the Raja of Banaras, Hindu, may at times have given an ideological edge to Balwant Singh's ambitions, though we should recall that some of the Raja's most intractable enemies were Hindu petty chieftains and that the Shi'a Nawabs were often highly catholic in religious matters.[10] What was at issue was less a matter of communal identity than of royal legitimation, for this was precisely what the Nawabs initially provided to the Banaras rulers: a legitimation that ultimately derived from the increasingly transparent premise of Mughal dominion. The Monas Rajputs of Bhadohi, for example, who were staunch rivals of Balwant Singh, held their land under an imperial grant from Shahjahan, and even after defeating them the Raja could not annex their territory until he had received the permission of the Nawab, the nominal Mughal representative in the region.

Power the Raja had, but he needed authority as well. Even though the Rajas'goal in relation to the Nawabs was a consistent one of independence, they could not afford to ignore the ground rules and had to continue to seek the sanction, even if it was ex post facto , of their superordinates, the Nawabs. (Cohn 1962:315)

The glories of the Indo-Persian cultural synthesis had long exerted a powerful influence upon the tastes of the Hindu elite in north India, but by the mid-eighteenth century the Mughal legacy must have seemed increasingly bankrupt. Delhi itself was devastatingly looted in 1739 by a Persian adventurer who carried off the legendary throne of Shahjahan. Urdu poets like Mir, who fled east to Awadh, sang of the downfall of the capital, its deserted streets and ruined bazaars (Russell and Islam 1968:19–20, 259–60). Within the century the reigning motif

[10] Note, for example, Asaf ud-Daula's patronage of one of the Ramanandi[*] subsects (Wilson 1862:57).

of Indo-Persian culture would become one of decline and lamentation over lost glory—a theme of little appeal to ambitious kings in search of positive and victorious symbols.

I suggest that the Banaras rulers' growing involvement, in the latter part of the eighteenth century, with the Ram[*] tradition—a preoccupation which they shared with other petty Hindu kings in the region—reflected among other things their need to cultivate an explicitly Hindu symbol of royal legitimacy, and thus to achieve ideological as well as political independence from the Nawabs. In seeking to revive a Vaishnava ideal of divine kingship and harmonious but hierarchical social order, they turned not to the figure of Krishna (whose legend had, during preceding centuries of Muslim ascendancy, come to be almost exclusively focused upon a pastoral and erotic myth),[11] but to that of Ram, whose myth had retained a strong martial, imperial, and sociopolitical dimension, expressed most clearly in the vision of Ramraj[*] , or the golden age of Ram's universal rule, and in the hero's role as exemplar of maryada[*] , a term that implied both personal dignity and social propriety. Moreover the Ram tradition's emphasis on social and political hierarchy, and on the properly deferential behavior of subjects and subordinates, could serve as chastening examples to the Rajas' rebellious underlings. That all these ideals had found expression in a brilliant vernacular epic which had already won a vast following throughout the region only enhanced the ideological utility of the tradition. Accordingly, it was to Ram and to the Manas[*] that the Rajas turned for a validating model of religiopolitical authority. The resulting trend toward elite patronage of the epic turned many courts of the period into centers of Manas performance and scholarship. Not surprisingly, the prospect of generous royal patronage had the effect of awakening greater interest in the Hindi epic among Brahmins, who began increasingly to claim the privilege of authoritatively expounding its verses.

A further motive for the Banaras kings' patronage of the Ram tradition may have been their desire to maintain amicable relations with the economically and militarily powerful Ramanandi[*] order (Burghart 1978:126, 130; Thiel-Horstmann 1985). A mobile population that was difficult to monitor, these mendicants or sadhus often traveled in armed bands, served as mercenaries in royal armies, and controlled the trade in certain commodities (Cohn 1964:175–82); given the unstable conditions of the period, aspiring kings may well have been concerned to remain on favorable terms with them. The Banaras kingdom was in relatively close proximity to three important Ramanandi centers: Chitrakut in the southwest, Janakpur in the northeast, and Ayodhya in the

[11] David Haberman suggests that the de-emphasis on heroic and royal Vaishnava myths in favor of the legends of Krishna Gopal paralleled "a gradual (Hindu) retreat from the Muslim-dominated sociopolitical sphere" (Haberman 1984:50)

northwest. It was in part through conspicuous patronage of the Ramanandis[*] —especially at the time of the Ramlila[*] festival, when thousands of sadhus were invited to set up camp in the royal city and were fed at the Raja's expense—that the Banaras rulers succeeded in turning their upstart capital, on the "impure" eastern bank of the Ganges, into a major center of pilgrimage, a move that must have conferred positive economic benefits even while it served to advertise their prestige and piety.

The troubled reign of Chait Singh (1770–1781), whose succession to the throne was disputed by the Nawab and who was eventually deposed by the British, nevertheless saw the commencement of an ambitious building project: an enormous temple with a one-hundred-foot spire visible for miles around, flanked by a vast tank and an expansive walled garden containing several small pavilions. The temple's iconography shows a deliberate blending of Vaishnava and Shaiva motifs,[12] and its construction may be interpreted as a major ideological statement on the part of the fledgling dynasty, which was concerned with its status in the eyes of the conservative Shaiva Brahmins across the river.[13] Possibly intended as the principal temple of a new royal capital, the structure eventually acquired the name Sumeru, after the mythical world-mountain, and came to be utilized as one of the settings for the royal Ramlila pageant.

The greatest flowering of Manas[*] patronage at the Banaras court began during the reign of Balwant Singh's grandson, Udit Narayan Singh (1796–1835). By his time, real political power in the region had passed to the East India Company,[14] but this fact only reminds us that the symbols used to legitimate authority can serve equally well to compensate for its loss. Moreover, the imposition of de facto British rule brought a respite from the military rivalries which had preoccupied earlier kings, and freed Odita Narayan to devote his time and energy to Manas patronage, to which he was in any case strongly inclined. During his long reign, Manas manuscripts were assiduously collected and copied at the court, and the most eminent ramayani s[*] (experts on the epic) were invited to expound before the Maharaja, or present ingenious resolutions to shanka s[*] ("doubts" or problems) concerning the text. The king encouraged some of these scholars to produce written

[12] On this temple's connection to the Ramlila, see Shrimati Chhoti Maharajkumari 1979:43–45.

[13] By caste the Rajas were Bhumihars, a cultivator group that claimed Brahmin status.

[14] The Company assumed control of the civil and criminal administration of Banaras city and province after 1781 and confined the Maharaja's authority to a separate "Banaras estate" in 1794; Imperial Gazetteer , pp. 134–35.

tika s[*] ("commentaries"), which would preserve their profound interpretations. One of those who enjoyed Udit Narayan's patronage, Raghunath Das "Sindhi," wrote that the Raja in fact sponsored three tika s, only one of which, Raghunath's own Manas-dipika[*] ("Lamp of the Manas[*] "), was in written form. The other two "commentaries" were a magnificently illuminated manuscript of the epic, and the local Ramlila[*] itself, which was expanded into a month-long pageant, and for which Udit Narayan transformed his capital (now dubbed Ramnagar—"Ram's city") into a vast outdoor set (Avasthi 1979:57).

The fact that "commentary" was understood to refer to more than merely written works was characteristic of the Manas tradition, and even the textual tika s produced during this period were usually derivative of the oral performance milieu. Such works often developed from the kharra[*] , or "rough notes," made by expounders in the margins of their Manas manuscripts to serve as reminders to themselves in performance. Some were deliberately enigmatic, such as Manas-mayank[*] ("Moon of the Manas "), composed by Shivlal Pathak (c. 1756–1820), a protégé of Raja Gopal Saran Singh of Dumrao and a frequent guest at Ramnagar. Pathak's "commentary" was in the form of kut[*] , or "riddling" verses, and depended upon his own verbal explanations; the key to understanding it is said to have been lost at his death (Sharan 1938:912). Indeed some of the most famous ramayani s[*] are said to have refused all requests to "reduce" their interpretations to writing. The legendary Ramgulam Dvivedi of Mirzapur (fl. c. 1800–1830) was believed to have obtained his extraordinary oratorical gifts and profound insights into the epic as a boon from Hanuman, who expressly forbade him ever to compose a written tika[*] (B. P. Singh 1957:429).

Anjaninandan Sharan, a scholarly sadhu of Ayodhya who wrote a brief but valuable history of the Manas-katha[*] tradition,[15] has recorded a story concerning Ramgulam that is richly suggestive of the virtuosity and prestige of expounders during this period. It is said that the Maharaja of Rewa, Vishvanath Singh (1789–1854), a friend and contemporary of Udit, Narayan and himself the author of a commentary on Tulsi's song-cycle Vinay patrika[*] , once met Ramgulam during the Kumbh Mela festival at Allahabad. When the great ramayani[*] graciously offered to speak on any topic of the king's choosing, the Raja immediately quoted the first line of the famous nam[*]vandana[*] ("Praise of the Name") in the first canto of the Manas , stating that he had great curiosity concerning its meaning: "I venerate Ram[*] , the name of Raghubar, / the cause of fire, the sun, and the moon" (1.19.1). Ramgulam agreed to ex-

[15] See Sharan 1938; he was the compiler of the twelve-volume Manas-Piyush[*] (Ayodhya, 1925–1932), an encyclopedic commentary that incorporated the insights of many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century expounders.

pound this verse on the following afternoon from 3:00 to 6:00 P.M . Then, according to Sharan,

[he] went on for twenty-two days, with ever new insights, expounding this one line; and whatever interpretation he would put forth on one day, he would demolish the next, saying it was not right. Finally on the twenty-third day the Raja, filled with humility, said, "You are indeed a fathomless ocean, and I am only a householder with all sorts of worries on my head. It is difficult for me to stay on here any longer. . . . " Then with much praise he requested leave to depart and returned to Rewa. (1938:921)

Mention must also be made of the sadhu known as Kashthajihva Swami ("wooden-tongued" swami, d. c. 1855),[16] who was a younger contemporary of Raja Odita Narayan and the guru of his son. An accomplished poet with a unique style, he composed more than fifteen hundred songs, several hundred of which concern problems in the Manas[*] . He was closely involved in the development of the Ramnagar Ramlila[*] , the performance script of which still contains a number of his songs. At the Raja's request he wrote a short Manas commentary, Ramayan[*] paricharya[*] ("service of the Ramayan "), which the king then expanded with his own Parishishta[*] ("appendix"). These texts, however, like Shivlal Pathak's "riddling" verses, were written in an obscure style; to clarify them, Baba Hariharprasad, a nephew of the Raja, who had become a Ramanandi[*] ascetic, composed an additional commentary entitled Prakash[*] ("illumination"). The composite tika[*] with its grand title was published in 1896 and was held in high regard by expounders of the period.

The reign of Ishvariprasad Narayan Singh (1835–1889) has been called "the golden age of the Manas " (S. Chaube 1976, 3:121), for under his patronage the Ramnagar court became the preeminent seat of Manas patronage and scholarship. The king's legendary ramayani[*]sat-sang s were graced by the "nine jewels" of the court—the most eminent Manas scholars of the day, including Kashthajihva Swami, Munshi Chhakkan Lal (principal pupil of Ramgulam Dvivedi), and Vandan Pathak, who was famed for his ingenious and even playful interpretations.[17] The king also sponsored a major revision of the royal Ramlila,

[16] There are various explanations of how this sannyasi got his peculiar name; see Sharan 1938:918, B. P. Singh 1957:450.

[17] Pathak is said to have boasted that he did not concern himself with anything that was not mentioned in the Manas . Once while he was performing, an old woman presented him with a clay dish containing a certain savory. Pathak quickly pocketed the gift, but someone in the crowd jokingly called out, "Maharaj, what does this have to do with the Manas? " Pathak, who was renowned for his great presence of mind when expounding, instantly quoted a line from Bal[*]kand[*] (1.35.8), the last word of which made a pun on the colloquial name for the dish in which the woman had presented her gift (recounted by C. N. Singh, interview, Feb. 13, 1984).

allegedly under the direction of the Banarsi writer Harishchandra, who modernized and expanded the dialogues and set the production in the form in which it was to gain all-India fame (Avasthi 1979:81–88).

Although I have emphasized royal sponsorship, it should be noted that Manas[*] patronage was not confined to the court, for the king's fascination with the epic was shared by the nobles and wealthy landowners of the area. According to Vibhuti Narayan Singh, the present titular Maharaja, rajas and zamindars during the nineteenth century "vied with one another" in their efforts to promote the epic, and intimate knowledge of the text was regarded as a mark of cultural sophistication as well as piety.[18] The Manas acquired the status not merely of a sacred book but of a cultural epic; hundreds of its verses entered popular speech as aphorisms, and its stanzas were set to seasonal melodies like kajli[*] and chaiti[*] and performed by urban and rural folksingers.[19] By 1880 F. S. Growse would observe that Tulsi's epic "is in everyone's hands, from the court to the cottage, and is read, or heard, and appreciated alike by every class of the Hindu community, whether high or low, rich or poor, young or old" (Growse 1887:lv). And while their Indologist colleagues devoted themselves to the study of the Sanskrit classics, British administrators and missionaries, out of expedience, studied the Manas . George Grierson was to recall: "Half a century ago, an old missionary said to me that no one could hope to understand the natives of Upper India till he had mastered every line that Tulsidas had written. I have since learned to know how right he was."[20]

The Book in Print

Other developments during the nineteenth century significantly altered the pattern of Manas patronage and would in time affect even the structure of performances. One was the introduction of print technology, an innovation first sponsored by the British but quickly adopted by Indians. Among the first printed versions of the Manas was an 1810 edition published in Calcutta, the city in which, partly due to the presence and patronage of the East India Company's College of Fort William, popular publishing in Hindi as well as Bengali had its start. Thereafter a steadily increasing number of both lithographed and typeset editions documents the westward expansion of publishing, and especially the dramatic rise of Hindi publishing in Banaras beginning at about mid-

[18] Vibhuti Narayan Singh, interview, Aug. 11, 1983.

[19] This genre has been described by N. Kumar (1984:178–236); see also chapter 2 of Lutgendorf (1987) and chapter 3, this volume.

[20] Quoted in Gopal (1977:x); that knowledge of the Manas was considered essential for a civil administrator was also noted by Growse (1887:lvi).

century.[21] The greatest expansion in Manas[*] printing occurred after 1860, however; during the next two decades at least seventy different editions of the epic appeared from publishing houses large and small, representing virtually every moderate-sized urban center in north India.[22] Especially notable are the Gurumukhi script editions which began appearing from Delhi and Lahore after 1870, versions with Bengali commentaries that were printed in Calcutta in the 1880s, and Marathi and Gujarati editions issued from Bombay and Ahmedabad beginning in the 1890s. Clearly the literate audience for the Manas was growing during the latter part of the century and was spreading far beyond the traditional heartland of the epic and of its Awadhi dialect. Notable too is the steadily increasing size of the editions: whereas those published prior to 1870 had averaged four to five hundred pages and offered only the epic text, those issued in succeeding decades more typically ran to a thousand pages and included prose tika s[*] , glossaries of archaic words, ritual instructions, mahatmya s[*] (eulogies of the text), explanations of mythological allusions, and biographies of Tulsidas—all designed to serve the interests of a literate but geographically and culturally heterogeneous audience. The authors of the commentaries offered in these expanded editions were, like the editors of the earlier generation of unannotated texts, traditional scholars known for their oral exposition of the epic; the reputations of such famous ramayani s[*] as Raghunath Das of Banaras and Jvalaprasad Mishra of Moradabad were greatly enhanced by their association with such popular editions as those of Naval Kishor Press of Lucknow and Shri Venkateshvar Steam Press of Bombay (cf. numerous editions of Das 1873 and Mishra 1906).

The advent of mass printing eliminated the expensive and time-consuming process of scribal manuscript copying and made literature available to the middle classes. One consequence of this development was the fact that literate persons acquired the potential for a kind of participation in sacred literature that had formerly been the domain of a specialist elite. Books could be "read" of course, for private enjoyment and edification, but equally important, sacred books could now also be recited by nonspecialists. The meritorious activity of daily path[*] (recitation), rooted in the ancient belief in the spiritual efficacy of the sacred word, was greatly facilitated by the ready availability of revered texts. By the end of the nineteeth century, many bazaar editions of the Manas had begun to be annotated according to regular schemes of nine- and thirty-day recitation (navah[ *]parayan[*] and mas[*]parayan ) and in-

[21] On the early history of printing in north India, see McGregor 1974:70–74.

[22] The figure is based on my (still incomplete) file of early editions, drawn from the catalogues of the British Museum and the India Office Library, M. Gupta (1945), Narayan (1971), S. Chaube (1976), and several private collections.

cluded directions for accompanying rituals as well as descriptions of the spiritual and material benefits to be expected thereform. Daily Manas[*] recitation became part of the household ritual of countless pious families, and one result was an audience that was both more knowledgeable with respect to the text and more discriminating with respect to oral exposition. The resolution of "doubts" (shanka s[*] ) concerning Manas passages became an important duty of expounders, some of whom published shankavali s[*] (collections of common textual problems with their "solutions");[23] these were among the tools utilized in the training of aspiring ramayani s[*] .

Two related developments also need mention here. The first, of special relevance to the Banaras region, was the rise of the Hindi language movement during the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century (see chapter 6). Although most advocates of Hindi and of Devanagari script favored the use of the Khari[*] Boli[*] dialect for prose purposes, the increasing association of Hindi with Hindu communal identity led to renewed interest in bhakti poetry among the university-educated elite, and to the founding of the Nagari[*] Pracharini[*] Sabha[*] in 1893, an organization for the promotion of Hindi, which soon undertook the preparation of a "critical edition" of the Manas (Dvivedi 1903).

The second and contemporaneous development was the rise of what came to be known as the Sanatan[*] Dharm movement—the self-identification of mainstream, socially conservative Hindus as adherents of an "eternal religion." During the second half of the nineteenth century, popular Hindu beliefs and practices came under increasing criticism both from Christian missionaries and from reform movements like the Arya Samaj[*] and the Brahmo Samaj. There was a strong element of reaction in the Sanatani[*] stance, and a tendency for self-definition in largely negative terms: that is, those who were not Aryas or Brahmos, Christians or Westernizers, who did not advocate widow remarriage, initiation of untouchables, abandonment of image-worship, and so forth.[24] But one of the more positive identifications to which traditionalists could point was faith in the Manas , the most accessible of scriptures and mainstream text par excellence—a bhakti work that still preached reverence for cows and Brahmins, claimed to be in accord with a comfortably undefined "Veda," offered a satisfying synthesis of Vaishnavism and Shaivism, and in the minds of many devotees, stood at one and the same time for fervent devotional egalitarianism, the

[23] An early manuscript example is Manas shankavali[*] of Vandan Pathak (mid-19th cent.); printed examples include J. B. Singh (1918), Din (1942), and Ramkumar Das (n.d., 1950s).

[24] On the antagonism between Aryas and Sanatanis[*] in Punjab, see Jones 1976: 108–12.

maintenance of the social status quo, and even a kind of nationalism in that it countered the British colonial ethos with an idealized vision of a powerful and harmonious Hindu state.[25] Sanatani[*] leaders, whose rhetoric was increasingly colored both by anti-British and by anti-Muslim sentiments, came to view the Hindi epic as an inspired response to a Dark Age particularly characterized by "foreign" domination of India.

Undoubtedly the most prominent Sanatani spokesman in the early twentieth century was the Allahabad Brahmin Madanmohan Malaviya, who led the campaign for the establishment of a Hindu University in Banaras (Bayly 1975:215–17). A tireless advocate of cow protection and Devanagiri script, Malaviya also issued a call for Manas[*]prachar[*] —the promulgation of Tulsi's epic:

Blessed are they who read or listen to Gosvami Tulsidas-ji's Manas-Ramayan[*] . . . . But even more blessed are those people who print beautiful and inexpensive editions of the Manas and place them in the hands of the very poorest people, thus doing them priceless service. . . . At present Manas-katha[*] is going on in many towns and villages. But wherever it is not, it should begin, and its holy teachings should be ever more widely promulgated. (Poddar 1938a:52).

One milestone for the Sanatani movement in the 1920s was the founding of the Gita Press of Gorakhpur, publisher of the influential monthly Kalyan[*] (Auspiciousness). The Press answered Malaviya's call by churning out low-priced Manas editions of every size and description,[26] sponsored contests to test children's knowledge of Manas verses, encouraged mass recitation programs, and frequently published written exegesis by eminent ramayani s[*] like Jayramdas "Din" and Vijayanand Tripathi.

Tripathi deserves special mention, for he was the leading Manas expounder in Banaras during the mid-twentieth century. The son of a wealthy landlord, he had no need to seek outside patronage for his katha[*] , and performed daily on the broad stone terrace of his house in the Bhadaini neighborhood, not far from Tulsidas's own house at Assi Ghat. His enthusiastic listeners are said to have included both Malaviya and Bankeram Mishra, the mahant (hereditary proprietor) of the powerful Sankat[*] Mochan Temple. Tripathi was much influenced by the conservative Dasnami[*] ascetic Swami Karpatri, whose monthly magazine

[25] Cf. Norvin Hein's observation that "[Ramraj[ *] ] was one of the few vital indigenous political ideas remaining in the vastly unpolitical mind of the old-time Indian peasant" (Hein 1972:100). On the role of the Sanatan[*] Dharm in fostering festivals, as well as the politicization of Ramlila[*] early in this century, see Freitag 1989.

[26] Their popularity may be gauged from the fact that the gutka[*] ("pocket edition") had gone through seventy-two printings as of 1983.

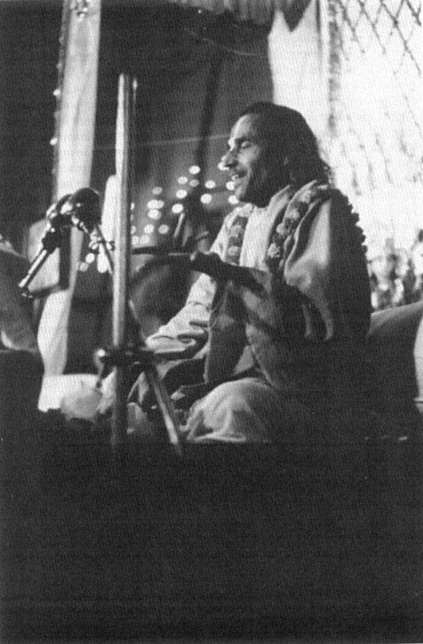

Fig. 3

The late Narayankant Tripathi, a venerable Ramcharitmanas[*] expounder, who

performed daily at the Sankat[*] Mochan Temple in Banaras (July 1983). Photograph

by Philip Lutgendorf.

Sanmarg[*] (The True Path) he edited from 1936 to 1942, and his admirers liked to emphasize that his Manas[*] interpretations were strictly in accord with vedic and shastraic precept and with the varnashram[ *] system of social hierarchy. His three-volume Vijaya[*]tika[*] on the epic was under-written by Seth Lakshminarayan Poddar, a wealthy merchant, and published by Motilal Banarsidass in 1955. Tripathi died soon afterward, but his influence continues to be felt through his many disciples, several of whom are presently among the leading Manas expounders in the city.[27]

Changing Styles of Performance

Even from the limited data available it is possible to make certain generalizations about the style and technique of Manas exposition during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The predominant mode of performance during this period was the sequential narration in daily

[27] Among his pupils were Sant Chhotelal (d. 1983), Ramji Pandey (chief ramayani[*] of the Ramnagar Ramlila[*] ), Baba Narayankant and Ramnarayan Shukla (resident expounders of the Sankat Mochan Temple [see figs. 3 and 4]), and Shrinath Mishra.

installments of part or all of the Manas[*] . The special time for such katha[*] was late afternoon, from about 4:00 P.M . until the time of sandhya-puja[*] at twilight. The venue of the performance was usually a public place, such as a temple courtyard, a ghat, or the open veranda of a prosperous home. The speaker, who was usually called a kathavachak[*] or ramayani[*] , recited from a manuscript or a printed text, though of course his performance was not strictly confined to the words before him; he could elaborate upon or digress from any line of the text, and the extent and ingenuity of his improvisation was limited only by his knowledge and training. That even early-nineteenth-century performances could feature very extended exposition of single lines is suggested by the story of Ramgulam's twenty-two-day tour de force; however, systematic exposition of a single prasang (episode), kand[*] (canto), or when possible, of the complete epic seems to have been the more usual practice.

Many expounders had their own characteristic interpretive approaches for which they were famous. Baijnath Kurmi (c. 1833–1885), a literary connoisseur and a rasik bhakta (a practitioner of the mysticoerotic path of devotion to Sita-Ram),[28] utilized the terminology of Sanskrit poetic and aesthetic theory, while the Kayasth[*] expounder Sant Unmani (c. 1830–1898), author of the commentary Manas tattva vivaran[*] (Explanation of the Essence of the Manas ), interpreted the epic from the standpoint of yoga doctrine, and his katha is said to have had special appeal for practitioners of hatha yoga (Sharan 1938:913, 918).

The economic rewards for such nitya , or "continuous" katha , were generally modest. An expounder would usually be engaged by a patron—a landlord or the mahant of a temple—who provided nominal support in the form of meals and accommodation and became the official shrota[*] , or "listener," and beneficiary of the katha , though the performances would also be open to the general public. In addition to the patron's support, the performer received the offerings in cash and kind which audience members made during the ceremonial worship at the close of each day's program. Performers were often hired on a long-term basis—for example, for an exposition of the complete epic, which might require two or more years. The ultimate completion of such an extended performance would be the occasion for a special celebration sponsored by the principal patron, who would then bestow a generous gift on the kathavachak . However, many illustrious performers are said to have had little interest in financial gain, and when, as sometimes happened, wealthy patrons rewarded their performances with

[28] The only major study of this neglected tradition is B. P. Singh (1957).

lavish gifts, they chose to offer the money for pious purposes such as the feeding of sadhus.[29]

Daily katha[*] tended to focus closely on the narrative, and the performer might even choose to confine himself, in the praman s[*] , or "proofs," he cited for his interpretations, entirely to the Manas[*] itself, or to the other eleven works of Tulsidas, which acquired a kind of canonical status for the tradition. A common technique was to discuss each significant word in a verse in terms of its usage elsewhere in the epic. A gifted practitioner of this approach would delight his listeners by quoting line after line in which a given word was used, showing the different shades of meaning Tulsidas gave it in various contexts, and creating a sort of "oral concordance."[30] The appeal of such exegesis for an audience that knew the Manas intimately and accepted it as the highest religious authority is suggested by the following comments made by a contemporary katha -goer at Sankat[*] Mochan Temple, where sequential exposition of the epic is still presented each afternoon:

When a man comes to hear katha on the Manas , he wants all the praman s to be from that, because that is what he knows. What is the use for him if the kathavachak[*] shows off his knowledge by quoting from here and there? It will only confuse him. In the old days they used to use the Manas only, with maybe the Vinay patrika[*] —enough! Now they like to quote this and that, Vedas and shastras.[31]

The erudite quoting of "this and that," especially of authoritative Sanskrit texts, was a technique particularly associated with Ramkumar Mishra (c. 1850–1920), the leading expounder in Banaras at the beginning of this century, and it seems to have reflected a conscious concern among performers and audiences to demonstrate that the teachings of the Manas were in accord with—approving of and "proven" by—the Sanskritic "great tradition." A pupil of the Kayasth expounder Chhakkan Lal and a favorite of Maharaja Prabhu Narayan Singh (1889–1931), Ramkumar has been credited with developing "the brilliant and fascinating (modern) style of katha performance" (Jhingaran 1976:20). So great was his fame and so pressing the demand to hear him that Ramkumar began to travel about and give katha in various places, staying only a short time in each. An annual performance series

[29] Ramkumar Mishra is said to have summed up his attitude with the formula "Wear coarse cloth, eat coarse food; you are entitled to only enough [of the offering] to keep this body alive" (Sharan 1938:926–27).

[30] On the use of a similar technique in Christian monastic discourse, see LeClercq 1961:79–83.

[31] S. Singh, interview, Feb. 10, 1984.

Fig. 4

Pandit Ramnarayan Shukla expounding the Ramcharitmanas[*] during the katha[ *

] festival at Gyan[*] Vapi[*] (November 1982). Photograph by Philip Lutgendorf.

in Banaras became a celebrated event, attracting crowds so great that the organizers were forced to make arrangements whereby people could reserve space in advance, to ensure getting a place to sit. A two-month exposition of the whole of Sundarkand[*] (the fifth canto of the Manas[*] ) in the courtyard of Ayodhya's largest temple was said to have been such a success that other expounders in the city—a traditional center for daily katha[*] —found themselves without audiences for the duration (Sharan 1938:926–27).

In time regular "circuits" developed, frequented by other traveling expounders, who likewise began to give shorter programs. This in turn affected the economic aspects of the art; since performers were no longer maintained by an individual patron or community on a long-term basis, they began to accept set fees for their performances. The patrons of this kind of katha were drawn less from the landed aristocracy than from urban commercial classes; indeed, one observer has termed the new style "Baniya (mercantile) katha ."[32] The underlying causes of this shift in patronage were the economic and political developments of the latter half of the nineteenth century, which precipitated the decline of the rajas and zamindars and the rise of urban mercantile communities such as the Marwaris.[33] Like the petty Rajputs and Bhumihars of the preceding century, the "new men" of the urban corporations found themselves in possession of wealth but in need of status, a dilemma which they resolved, in part, through conspicuous patronage of religious traditions.

Under mercantile patronage, katha performances began to be held later in the evening—after 9:00 P.M ., when the bazaars and wholesale markets closed. The leisurely and informal daily katha of the late afternoon, in which the performer was assured of a regular audience and a steady if modest income, was replaced by a more elaborate form of performance, held on a few consecutive nights before large crowds, requiring more complicated arrangements such as mandap s[*] and lights, and at which the performer's talent might be rewarded with a considerable sum of money. Since the expounder—who was increasingly honored with the exalted title vyas[*] —typically had only a single hour in which to display his talents, he abandoned systematic narration in favor of extended improvisation on very small segments of the text. The chosen excerpt became the basis for a dazzling display of rhetoric and erudition, backed up by citations of numerous Sanskrit works—a practice sure to win approval from the new class of connoisseurs. Such presentations, for which the performer typically prepared extensive notes in

[32] C. N. Singh, interview, July 19, 1983.

[33] On the economic changes of the period, see Bayly 1983:269–99; on the rise of a commercial community, see Timberg 1978.

advance, began to resemble academic lectures or speeches, although, like narrative katha[ *] , they were still delivered extempore and were liberally interspersed with verses from the epic, which were usually sung or chanted. Storytelling survived largely in the form of anecdotes, and the term pravachan —"eloquent speech"—became the preferred label for such performances, rather than the more "story"-oriented term, katha .

A subsequent and related development was the sammelan , or "festival": a large-scale, usually urban performance, which gave audiences the opportunity to hear, in one location, a selection of the most renowned Manas[*] interpreters of the day. The first such festival in Banaras was the Sarvabhauma Ramayan[*] Sammelan (universal Ramayan festival) organized in the mid-1920s under the auspices of the Sankat[*] Mochan Temple, a shrine to Hanuman reputedly established by Tulsidas himself but which in fact rose to prominence only in this century. Additional financial backing came from Munnilal Agraval, a prominent Marwari businessman.[34] The festival began on the evening following the full moon of Chaitra (the traditional birthday of Hanuman) and continued for three nights, with a series of vyas es[*] featured at each program. In addition to Banarsi expounders, well-known out-of-town performers were invited, their travel and lodging expenses were met, and they were given a cash dakshina[*] —the term applied to a gift to a Brahmin preceptor. The Sankat Mochan festival became an annual event, and its prestige made it an important platform for aspiring vyas es. To be invited to perform there and to make a favorable impression on the discriminating Banaras audience could represent a major break-through into a successful performance career, and some performers today still fondly recall their "debuts" there.

The same combination of Sanatani[*] leadership and mercantile financing that supported this festival was to lead in time to the mounting of even more elaborate programs, the prototype of which was the Shri[*] Ramcharitmanas[*] Navahna[*] Parayan[*] Mahayajna[*] (Great Sacrifice of The Nine-Day Recitation of Shri Ramcharitmanas ) organized in the mid-1950s at Gyan[*] Vapi[*] , in the heart of the city.[35] The instigation for this festival came from Swami Karpatri, who had become a celebrated figure because of his vociferous denunciation of the "secular" policies of the Congress government and his founding of a political party that promised to bring back "the rule of Ram" (Weiner 1957:170–74). Financial backing came from the Marwari[*] Seva[*] Sangh, a charitable trust organized by prosperous and socially conservative merchants.

[34] Nita Kumar, writing on Ramlila[*] patronage, has discussed the typical collaboration of merchants and religious leaders in organizing such events (1984:274).

[35] "Well of wisdom"; the site marks the location of a temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1669; see Eck 1982:127.

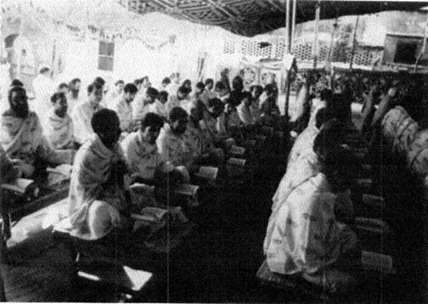

Fig. 5

One hundred and eight Brahmins chant the Ramcharitmanas[*] during an annual,

nine-day festival held at Gyan[*] Vapi[*] (November 1982). Photograph by Philip

Lutgendorf.

The special innovation of this annual festival was that it was organized around a nine-day ritualized recitation of the entire Manas[*] , conducted on the model of a vedic mahayajna[*] ("great sacrifice"). An auspicious hundred-and-eight Brahmins, identically clad in ochre robes, sat in long rows in a huge mandap[*] , surrounded by a circumambulatory track, and mechanically chanted the Manas for five hours each morning (see fig. 5), their voices echoing throughout much of downtown Banaras over a network of some three hundred loudspeakers. Other features included a diorama of opulently costumed clay images of Manas characters, special performances to commemorate important events such as Ram's[*] wedding and enthronement, and a climactic procession to the city's main ghat to immerse the images.[36] The public responded warmly, and merchant families vied with one another to engage in the meritorious activity of offering refreshments and gifts to the Brahmins—each donor's name being trumpeted over the public-address sys-

[36] The use of pratima s[*] (clay images) probably reflects the influence of Durga Puja observances, which have proliferated in Banaras during the past half century; see N. Kumar 1984:322.

tem.[37] As in a vedic yajña , the "breaks" in the sacrifice (in this case, the evenings from 7:00 P.M . on) were devoted to storytelling, that is, katha[*] . Lesser-known or aspiring vyas es[*] were invited to speak during the early part of the evening when the crowd was still assembling, to be followed later each night by three featured performers. In certain respects, the Gyan[*] Vapi[*] festival and its many spinoffs (by 1983 more than a dozen such annual programs were being held in Banaras) have come to resemble classical concerts or Urdu mushaira s (poetry recitation festivals). As at these performances, a strict protocol is observed, with the most highly respected performers invariably appearing last, and prominent connoisseurs often not arriving until just before the most famous vyas[ *] takes his place on the dais. Dress is traditional and often opulent, the atmosphere is formal, and there is frequently an element of tension and competition among performers, especially younger ones who are still establishing their reputations. In 1982 and 1983, the Gyan Vapi and Sankat[*] Mochan festivals each paid on the order of Rs. 250 per evening to featured performers, apart from travel and lodging expenses. This is a comparatively modest dakshina[*] for a successful vyas , but these festivals compensate by the prestige and exposure they offer, and so performers are willing to accept lower fees than they might command elsewhere.

One controversial development of recent years has been the advent of women performers, a number of whom have gained considerable renown (Upadhyay 1984:16–17). Several kathavachika s[*] were trained by the Banarsi expounder Sant Chhote-ji (himself a pupil of Vijayanand Tripathi) and have begun to make careers for themselves despite the continuing opposition of some conservative males who argue that women lack the adhikar[*] (spiritual "authority") to expound the epic. Women have probably always made up an important component of the katha audience, and a recent article in a popular Hindi magazine notes:

The ironic thing is . . . that there will often be a preponderance of women among the listeners. So those who are opposed [to women expounders] are clearly saying, "Yes, of course you can listen to katha , you can recite the Manas[*] too; but you can never sit on the dais and give katha !" (Jhingaran 1976:23)

Another trend, which has developed largely since the 1960s, is the increasing vogue among wealthy patrons for private performances, often in the patrons' homes or business institutions. The sponsors of this

[37] So lucrative has the program become that there is intense competition for the 108 places. I was told that a reciter could expect to take home upwards of Rs. 400 in cash, plus gifts of food, cloth, and even stainless steel utensils; S. Pandey, interview, Feb. 23, 1984.

new form of "aristocratic" patronage include, appropriately enough, many of the "princes" of Indian industry, most notably the Birla family of Marwari industrialists, who manufacture everything from fabrics to heavy machinery and have also been conspicuous in the construction and endowment of temples and dharmshalas. The Banarsi expounder Ramkinkar Upadhyay, who is widely acclaimed as the greatest contemporary vyas[ *] , has enjoyed Birla patronage for roughly two decades, and each spring at the time of Ram[*] Navami[*] (the festival of Ram's birth), he performs for nine evenings in the huge garden of "Birla Temple" ("Lakshmi-Narayan Temple"), a marble-and-masonry colossus about a kilometer west of Connaught Place, the commercial heart of New Delhi. The prosperous looking crowd includes thousands of office workers, many of whom bring cassette recorders to tape the discourse. Just before he takes his seat on an elaborate canopied dais that resembles one of the aerial chariots seen in religious art, Ramkinkar is garlanded by the patron and official shrota[*] of the performance, the head of the Birla family and chief executive of its vast corporate empire, who is dressed for the occasion in the dhoti and kurta[*] of a pious householder.[38]

Such munificent patronage has considerably upped the financial ante in the world of katha[*] , giving rise to the oft-heard complaints that contemporary performers "sell" their art, or that they have "turned it into a business" (Jhingaran 1976:21). But while there is a tendency among aficionados to idealize the great performers of the past for their alleged noncovetousness, many expounders readily concede that katha is indeed a profession and speak willingly and even proudly of the fees they are able to command. An ordinary vyas —a local expounder who rarely or never receives invitations from "outside" (an important criterion of success in Banaras performance circles)—may receive as little as Rs. 11 or Rs. 21 for an hour's program, but not more than Rs. 100. Some daily kathavachak s[*] still perform on a monthly stipend of only a few hundred rupees, supplemented by listeners' offerings.[39] The middle range of performers consists of those who receive Rs. 100–300 for a performance; a considerable number of well-known vyas es[*] fall into this category, and if they perform regularly, as many of them do, their incomes may be substantial. However, the hourly fees of the highest

[38] In 1983 the chief patron was Basant Kumar Birla, son of Ghanshyam Das Birla. His wife, Sarla, heads the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, which sponsors Ramkinkar's performances in Delhi and Calcutta and also publishes more than a dozen volumes of transcriptions of his katha s[*] .

[39] An example is the young vyas who performs each evening under the auspices of the Chini[*] Kshetra Trust in a lane near Dashashvamedh[*] Ghat. He receives a monthly stipend of Rs. 150; V. Tripathi, interview, July 20, 1983.

ranking or "All-India" expounders (so called because of their frequent invitations to perform in such distant cities as Bombay and Calcutta) are considerably higher. Shrinath Mishra of Banaras, the principal pupil of Vijayanand Tripathi, has a normal minimum fee of Rs. 500 per hour, and often receives upwards of Rs. 1,000.[40] Ramkinkar Upadhyay is said to receive in the range of Rs. 1,500–3,000 for each talk. Given such financial incentives, the reported proliferation of performers in recent years seems understandable.[41]

One of the most significant effects of the new style of entrepreneurial backing of Manas[ *]katha[*] has been to shift the geographical center of the art away from smaller centers like Banaras, where the springs of courtly patronage have long been dry, to such urban industrial centers as Bombay, Delhi, Kanpur, and Calcutta, where the wealthiest patrons now reside. This trend is lamented by some Banarsi aficionados, for while the city remains a major center for katha and a training ground of performers, the most renowned exponents of the Banaras-based "Tulsi lineage" (the parampara[*] , or "tradition," which traces itself back, through Vijayanand Tripathi and Ramkumar Mishra, to Ramgulam Dvivedi and ultimately to Tulsidas himself)[42] can rarely be heard in the city these days, and indeed seldom appear even at public sammelan s, as most of their busy schedules are taken up with performances in the homes and institutions of their wealthy patrons. Expert vyas es[*] , like virtuosi of music and dance, tend to go where they are best rewarded, and when they leave, their art departs with them. This fact serves to underscore the observation that Manas katha is much more than impersonal "commentary" upon a written text: it is an individual performance art that unfolds within a specific milieu.

Conclusion

The art of Manas exposition is rooted in ancient Hindu traditions of oral mediation of sacred text, but it has undergone significant change during the past two centuries and is continuing to develop and change today. It is an extensive and multiform tradition, and much that has been said about it here has necessarily been in the nature of generalization, to which, in many cases, exceptions might be cited. If I have spoken of elite patronage of katha , I could point out that there are still vyas es who neither solicit nor desire lavish fees and who narrate the

[40] Shrinath Mishra, interview, Feb. 21, 1984.

[41] Jhingaran wryly remarks: "How many vyas es are there in Kashi nowadays? Even if one were to have a census taken by Hanuman, that energetic seeker who found the herb of immortality, perhaps for once even he would fail in his efforts!" (1976:20).

[42] A diagram of this parampara is given by Sharan (1938:910).

epic in the humblest of settings. I have emphasized the stimulating effect of royal patronage, yet there were expounders even in the eighteenth century who, it is said, gave no importance to kings, because they recognized only one monarch: Ramchandra of Ayodhya.

Now I must hazard one more generalization and invoke the oft-used concept of "Sanskritization"—the acquisition or confirmation of status through an appeal to established standards of orthodoxy—which I suggest has been a process central to the evolution of the Manas[*] tradition. When Tulsidas boldly undertook the fashioning of a religious epic in the language of ordinary people, he presented himself as only a fourth-hand transmitter of a divine katha[*] first uttered by Shiva to Parvati, and he was careful to point out its fundamental consistency with authoritative Sanskrit scriptures.[43] An epic which, in the charming hagiographic allegory of its attempted "suppression" by the Brahmins of Banaras at the bottom of a pile of sacred texts, irresistibly "rose up" from folk popularity to command elite recognition,[44] the Manas became, by the eighteenth century, the text of choice for the upwardly mobile and nouveau arrivé: the vehicle of legitimation for an upstart dynasty of Bhumihar tax collectors, the solace of rising mercantile communities, and the refuge of captains of industry seeking religious merit and good public relations. On a more modest scale, it continues to serve smaller institutions in similar fashion: thus the "All-India" Manas Sammelans mounted by tiny neighborhood temples bidding for a wider clientele—oddly enough, even goddess shrines (where one might expect some more appropriate text, such as the Devi[*]bhagavatam[*] ), because "the Manas is sure to bring in a crowd!"[45]

Even with the exodus of some of its most illustrious performers, katha remains a flourishing business in Banaras, and despite the predictable nostalgia for the past ("Back in those days you heard the real katha !"), successful contemporary performers concede that their status and fees have never been higher. People still flock to katha festivals, and middle-class devotees now exchange Ramkinkar cassettes with the same enthusiasm with which they trade film videos. Yet there is another dimension to "Sanskritization," which could affect the future of the tradition: the tendency of a new elite to reinterpret a popular tradition and attempt to make it, narrowly, its own. The example of the Ramanandi[*] sadhus may be pertinent: for several centuries they were one of the most liberal religious orders in India, accepting women, untouchables, and Muslims into their fold; but when, in the early eighteenth century,

[43] See, for example, the final shloka of the invocation to Bal[*]Kand[*] .

[44] See note 9.

[45] Interview with patron of Manas festival at Kamaksha[*] Devi temple, Kamachchha[*] , Banaras, Jan. 24, 1983.

they became desirous of royal patronage, they had to adapt themselves to a different set of rules: restrict entry to twice-born males, apply caste-based commensality practices to communal meals, and appoint only Brahmins as their mahant s (Burghart 1978:133–34; Thiel-Horstmann 1985:5).

The very existence of a brilliant Hindi Ramayan[*] —however "orthoprax" in its teachings—has remained so vexatious to some pandits that there have been repeated attempts to fabricate line-by-line Sanskrit versions and put them forth as the original "divine" Manas[*] , which Tulsidas had merely translated into vulgar speech—a "Sanskritization" so literal as perhaps to seem laughable, except that it is so doggedly implacable.[46] Now that Tulsi's language has come to be significantly at variance with the dominant spoken dialect, the tendency to "Sanskritize" his text takes on new meaning, and in the yajña s of Swami Karpatri and his followers perhaps more than simply words are being "sacrificed." For such ceremonies, the Gita Press prints instructions (in Sanskrit!) on the correct way to go about reciting the Manas , and the assembled Brahmins go through the concocted rituals with customary expertise. The chanting of an epic which in other contexts has served as a cultural link between upper and lower classes is here transformed into a specialist activity and spectator sport, and the text, now venerated as mantra, rumbles out of three hundred loudspeakers as a kind of auspicious Muzak. In such exercises, the cultural epic that won recognition as the "Fifth Veda"—the proverbial Hindu euphemism for the scripture one actually knows and loves—seems to run the risk of becoming more like one of the original four, "recited more, but enjoyed less," as one of my informants wryly remarked. The same man complained of Swami Karpatri, "He has made our Manas into a religious book—something people chant in the morning, after a bath. But in my family we used to sing it together at bedtime, for pleasure."[47]

The present vogue for yajña s is paralleled by the "Brahminization" of expounders[48] and the rise of private katha[ *] , and all these develop-

[46] These "duplicities" are mentioned by Sharan (1938:908). I too was sometimes told that "Tulsi only copied a Sanskrit Manas ; there are texts to prove it!" These claims recall similar efforts to "Brahmanize" Kabir (see Keay 1931:28); such attempts to "rewrite history" (as anti-Muslim propagandist P. N. Oak frankly labels his agenda) are perhaps more influential in shaping the popular conception of the past than either Indian or Western scholars realize.

[47] C. N. Singh, interview, July 19, 1983.

[48] The ranks of nineteenth-century expounders included many prominent non-Brahmins, such as Chhakkan Lal and Baijnath Kurmi. In recent years, however, there have been controversies over whether a non-Brahmin has the "authority" to sit on the vyas-pith[*] . Judging from my sources, mercantile sponsorship has tended to favor Brahmin performers, perhaps because the patrons represent status-conscious groups.

ments may be related to another process: the withdrawal of the new college-educated elite from what it perceives as "backward" or "rustic" entertainment forms such as Manas[*] folk singing and Ramlila[*] pageants (N. Kumar 1984:289). Although the epic continues to retain religious status for this elite, its performance forms are increasingly "refined" to limit personal participation, or are physically removed from the public arena. Thus in its newest transformation, the lively art of katha[*] —which has flourished for centuries on the streets and squares of Banaras and has offered at times a platform for social and political commentary[49] —seems to be becoming a sort of pious chamber music of the nouveau riche. But while this development may have significance for the future, it cannot obscure the present vitality and popularity of public katha , which continues to draw enthusiastic audiences and to remain a highly visible and (thanks to amplification) audible part of everyday life in Banaras.

[49] The political activities of kathavachak s[*] have been noted by Bayly (1975:105) and by Pandey (1982:147–48, 168–69).