Appendix B

The Dating of Pseudo-Aristeas

In the above discussion we reached the conclusion that Pseudo-Heca-taeus's On the Jews was not written before the Letter of Aristeas (ch. IV.3). The dating of the latter book can thus provide an additional post quem date for the composition of On the Jews.

Pseudo-Aristeas, who presents himself as a gentile courtier, claims to be recording events in the time of Ptolemy II (283-247) and to have played an active role in them. This has been universally rejected, and the book has been acknowledged as a pseudonymous Jewish work. Its date, however, is still much disputed, with various suggestions ranging from the late third century B.C. to the second half of the first century A.D. The evidence for the various datings has been rejected or responded to in a way that has left room for doubt.[1] There is, though, one passage in the book, within the geographical description of Judea, referring to the Jerusalem citadel (paras. 102-4),

[1] See the review of the main suggestions and the excellent evaluation of the pros and cons by Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.679-84. Note the penetrating references to the question of unity and the allegorical interpretations (679-80); the connection with the writings of Aristobulus, the Jewish philosopher (680 and n. 281, 683); the biblical associations in the geographical descriptions (681 and n. 282); the Ptolemaic official terminology (683); the Jewish-Egyptian background (683 and n. 289; cf. p. 285 below); and the arguments from the account of the harbors (682 n. 285; see further n. 7 below). As for Aristobulus, it should be added that one would expect this Jewish courtier to have referred to Aristeas, who is presented as a Ptolemaic courtier, in his report about the antiquity of the Greek translations (Eus. PE XIII.12.1-2) had he been acquainted with Pseudo-Aristeas.

that has not attracted much attention,[2] but may provide an approximate date for the composition of the book.[3] The conclusion is supported by other references and the Ptolemaic background; and there is no evidence that the passage is a later interpolation.

But before any discussion of this as well as of other relevant passages, some preliminary remarks must be made about the general character of the account of the Holy Land in the Letter and its sources of information. It has rightly been pointed out by many scholars that the book tends to idealize the Jewish country, Jerusalem, and the Temple by drawing on biblical stereotypes and associations,[4] rules taken from Hellenistic city building and architecture,[5] and especially on motifs borrowed from Greek and Hellenistic utopian literature.[6] There is no possibility of deciding whether the author had actually visited Jerusalem and the surrounding countryside. The utopian character of the account is no evidence: in describing what he regarded as a holy land and city, Pseudo-Aristeas may have preferred to follow the practice of some Hellenistic authors who idealized their subjects instead of faithfully reporting their experiences and true knowledge, which would certainly have been less exciting. It is therefore imperative to exercise caution in evaluating the geographical information. Only data that do not have biblical or Hellenistic sources of inspiration, and do not by themselves

[2] Graetz (1876) 295ff. and Willrich (1924) 90-91 identify the citadel with the Roman Antonia, which is certainly absurd in view of its manning by Jews and command by the High Priest (cf. Goodman in Schürer et al. [1973-86] III.682 n. 285). Hadas (1951) 12-13 is inconclusive. His discussion includes some mistakes on decisive points (e.g., the location of the pre-Maccabean citadel) and ignores Jewish sovereignty over the citadel. On the suggestion of Schürer, developed by Goodman, see pp. 275-76 below.

[3] Cf. in short Bar-Kochva (1989) 53 n. 83.

[4] See Tramontano (1931) 107; Hadas (1951) 64; Tcherikover (1958) 77-79; Bonphil (1972); Bickerman (1976-80) I.133; Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.681 and n. 282.

[5] See, e.g., Bickerman (1976-80) I.133-34.

[6] See Guttman (1928) 42ff.; Hadas (1951) 49-51; Tcherikover (1958) 64-68; Bonphil (1972) 131; Bickerman (1976-80) I.133-34. The latter is, however, mistaken in favorably evaluating the description of the course of the Jordan River (Pseudo-Aristeas 116; see Bickermann 128-29, 131). For its utopian and imaginary character, see Hadas 50, 147. Cf. Bonphil 139-40 on its Jewish parallels.

present an unrealistic picture, can be utilized for determining the date of the book.[7]

1. The Citadel and the Temple

Now to the passage itself. The author describes the citadel of Jerusalem. The pretext for the account is the visit of Ptolemaic delegates to the city for negotiations on the translation of the Torah and other matters. The following statements are relevant to the discussion (cf. Map 2, p. 555 above):

1. The citadel is situated on the highest place, controlling and overlooking the Temple and its court, so that the sacrificial ritual can be observed from it (paras. 100, 103).

2. It was planned by its founder and serves to defend the Temple (para. 104).

3. This protection is required in case of a revolt (neoterismos ) or an invasion by a foreign enemy (para. 101).

4. The local garrison consists of five hundred soldiers, all of whom are Jews (paras. 102, 104).

[7] Thus, for instance, the various attempts at determining the date according to the relationship between the ports and Jerusalem (Pseudo-Aristeas 115) fail to satisfy. The author describes the ports as serving the trade of Jerusalem according to philosophical conceptions of the ideal city-state (see, e.g., Plato, Leges 704-5: the influence of these conceptions on Pseudo-Aristeas 107-8, 115 is undeniable; cf. Arist. Pol. . 1327 ). The account therefore cannot be taken to indicate that the book was written at a time when Judea and the coastal plain were (or belonged to) one political unit. It should be added at this point that the names of the harbors mentioned in Pseudo-Aristeas (Ptolemaïs, Jaffa, Ascalon, and Gaza) can only indicate a dating before the destruction of Gaza by Alexander Jannaeus, and not a much earlier date. These four cities were traditionally known as the most important Palestinian ports, and it is only natural that less famous ports, which may have flourished in certain periods (like Strato's Tower, Dora, Iamnia,and Azotos), were not mentioned (contra Rappaport [1970] 38-41). A different approach, leading to the same results, is taken by Goodman: "Verse 115 probably does not refer to political control but only geographical proximity and the passage of trade (which would not be affected by the ports being in gentile hands), in which case it is irrelevant to the dating of the book" (in Schürer et al. [1973-86] III.682 n. 285). See also Hadas (1951) 146: "Aristeas does not necessarily imply that the Jews owned the ports but only that they used them."

5. These Jews are absolutely loyal to their country and religion (paras. 102, 104).

6. The garrison stands under the direct command of the High Priest (para. 103).[8]

7. The delegates of the Ptolemaic king had to receive permission from the High Priest to enter the citadel, and even then gained admission only with much difficulty, being disarmed before entering (paras. 103-4). The purpose was only to "see the sacrifices" from an observation point (para. 103), which obviously could not be allowed for gentiles in the Temple itself.

In contrast to the bulk of the account on Jerusalem and the Holy Land, this passage cannot be dismissed as an imaginary idealization or the like. The author speaks inter alia about the role of the citadel as a defense against an internal revolt, which in practice means uprisings against the High Priest involving the Temple. This is certainly anything but an idealization of the holy place and its admired guardian. Notably, the location of the citadel "on the highest place," soaring above the Temple, contradicts a passage in another context according to which the Temple was high above the city on the crest of a mountain "rising to a lofty height" (paras. 83-84). As was observed long ago, the latter account is imaginary and does not accord with the geography of Jerusalem. It was inspired by a combination of elements drawn from Hellenistic utopian literature and city planning,[9] as well as from Isaiah's celebrated vision of the End of Days (2.1).

In the case of the citadel, the author is drawn into another type of description by the need to explain its functions, and thus reveals more than he would wish. The role and location of the citadel, as well as other basic facts in themselves, sound quite realistic and, as we shall see, recall the specific situation in a particular period. The account does

[9] The location of temples on commanding heights, which is well known from classical archaeology, appears also in utopian literature; see, e.g., Euhe-merus ap. Diod. VI.1.6 (though it was far from the city: V.42.6). Cf. Plato, Critias 112, 113-15; Leges 778c-d, 848c-d; Arist. Pol. . 1331 . For the location of Jerusalem in the center of the country by Pseudo-Aristeas (para. 83), cf. Plato, Leges 745 .

not contain any biblical associations, and the role and command of the citadel do not recall Hellenistic practice, nor do they echo any Greek or Hellenistic utopia.[10] In view of the traditional Greek asylia, one can indeed be sure that the account of a citadel protecting a temple and supervised by a High Priest was not inspired by Hellenistic literature and practice.[11] In the absence of parallels, the author had to resort to reality and drew on his own personal knowledge. It does not require the direct acquaintance of an eyewitness to be able to write down the main features of such an account. They could have been reported in Alexandria by pilgrims returning from Jerusalem.

Taken as reflecting historical reality, it appears quite obvious that the account was not written while Jerusalem was under Hellenistic rulers, and the citadel manned by a foreign garrison. Even if one allows for some idealization in the account, the above conclusion remains valid: an Alexandrian writer who so emphatically stressed his loyalty (and that of the Jews) to the Ptolemaic dynasty would not have described what should have been the stronghold and symbol of Ptolemaic rule in Judea as an independent Jewish citadel unless he was actually recording the situation in his own time.

It has, though, been suggested that the account records a special situation that supposedly prevailed in Judea under the Ptolemies. According to this suggestion, foreign troops were stationed in the Jerusalem citadel only occasionally, and most of the time it was garrisoned by Jews.[12] This solution seems highly unlikely: the confrontation between the Ptolemies and the Jews in 302/1 and in the years of the Syrian wars,[13] the continuing, protracted hostility between the Ptolemies and the Seleucids over the future of Coile Syria, and the agitation of the

[10] Cf. the somewhat different phrasing of Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.681: "It is reasonable to assume that those details for which no biblical and Egyptian sources, and no apologetic reason for invention can be found, are more likely to derive from contemporary conditions than the author's imagination."

[11] Plato, Leges 848c-d, does not contradict this assertion: it relates to the security of the citizens and the city, not that of the temples.

[12] See Schürer (1901-9) III.611-12; Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.681-82.

[13] On the year 302/1, see p. 74 above. On the confrontation during the Third Syrian War, M. Stern (1962) 43; the Fourth Syrian War, Jos. Ant. XII.130 and perhaps also the trilingual stele from Pithom, 1.23 (see Gauthier and Sottas [1925] 54-56; but cf. the opposing view of Thissen [1966] 19, 60-63); the Fifth Syrian War, Ant. XII.131, 133, 135-36; Daniel 11.14.

pro-Seleucid party in the Jewish community—all these do not permit us to believe that the Ptolemies ordinarily entrusted the security of Judea to Jewish hands.[14] The reference to revolt, which would apply in this case to a Jewish anti-Ptolemaic rebellion, renders this suggestion even less acceptable. Furthermore, there is no indication in the passage of Jewish loyalty to the Ptolemaic kingdom, or that the fortress in any way served Ptolemaic interests. Such assertions would be expected even more in a report on a visit by a Ptolemaic delegation. The author stresses instead the dedication of the Jewish troops to their patris (para. 102). In addition, the delegation gains access to the fortress with much difficulty, is disarmed, and even then is able only to "see the sacrifices" (para. 103). There is no indication that they were allowed to review the military installations from inside.

It should also be pointed out that the location of the fortress on the "highest place" (para. 100), overlooking the Temple altar (103), and the stipulation that its purpose was to protect the Temple (104) make it difficult to identify the citadel with the Akra known from the Ptolemaic and Seleucid periods. The latter was situated a few hundred meters south of the Temple, on a hill considerably lower than the Temple Mount,[15] and its purpose was to control the city, not the Temple. And there was not and could not have been any other fortress in Jerusalem under Hellenistic rule.[16] These data do not in themselves constitute decisive proof, since the author could still have made a mistake in determining the exact location of the citadel, but they certainly do not suggest an early dating.

[14] Ant. XII.133 does not imply that Ptolemaic troops were only occasionally assigned to the fortress, as argued by Schürer (and Goodman in Schürer et al. [1973-86] 682). They were previously expelled by the Jews in the first stage of the Fifth Syrian War, when Antiochus III invaded Syria (in the year 202/1; see Ant. XII.131, 135; Polyb. XVI.22a; on the stages of that war, see Bar-Kochva [1979] 146, 256, and bibliography there).

[15] See the detailed discussion in Bar-Kochva (1989) 445-65. The general location of the Seleucid Akra on the southeastern hill was agreed upon by Schürer et al. (1973-86) I.154 n. 39 and Goodman therein, III.681, as well as by most philologist-historians.

[16] See my arguments in Bar-Kochva (1989) 462-65, in contrast to Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.681. The latter is forced to presume that Hyrcanus only restored the Temple citadel (n. 283).

It can, therefore, be said that the status of the citadel and its garrison and command indicate a period of Jewish independence, namely the time of the Hasmonean state. This conclusion is supported by further considerations: the role of the High Priest as supreme military commander, taken together with the references to his authority in civil matters (paras. 81, 122), recalls the appointments bestowed upon the early Has-moneans since the time of Jonathan;[17] the need to protect the Temple from foreign invasions and internal unrest is understandable for the early Hasmonean rulers, in whose time there was great sensitivity with regard to possible new attacks on the Temple by foreign enemies, and religious sects disputed the ritual practices performed in the Temple and the very right of the Hasmoneans to serve there as High Priests. Given this general dating to the Hasmonean period, the intention to use the citadel to protect the Temple and its location "in the highest place" suggest its identification with the Baris, the Hasmonean citadel built north of the Temple in the place of the later Antonia (Ant. XIII.307, XV.409; Bell. V.238-47). The Baris did indeed tower over the Temple and also served other purposes connected with the Temple, such as safeguarding the ceremonial garments of the High Priest (Ant. XVIII.91).

The construction of the Baris can thus provide a post quem date for Pseudo-Aristeas. Josephus mentions in the narrative of the Herodian and the Roman period that it was built by John Hyrcanus (Ant. XV.403, XVIII.91). If one tries to be more precise and date the construction within Hyrcanus's reign of three decades (135-104 B.C. ), one can be sure that it was built only after 129, when Hyrcanus regained his independence after the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes in the eastern provinces. It was not built immediately after 129: I Maccabees, written not long after that year,[18] mentions, in praise of Hyrcanus's achievements, only the rebuilding of the city wall, and not the fortress (16.23). It is true that Josephus's account of the period of John Hyrcanus (Ant. XIII.230-300) does not record the building of the fortress, but he does not refer to

[17] On the sovereignty of the High Priest as an argument for the dating of the book to the time of the Hasmonean rulers, see M. Stern (1983) 225.

[18] On the dating of I Maccabees, see Bar-Kochva (1989) 158-66. The conclusion reached below regarding the dating of Pseudo-Aristeas to the years 118/16-113, which is based on a number of arguments aside from the date of I Maccabees, supports the view that the latter book could not have been composed long after the year 129.

the reconstruction of the wall, either. Josephus devotes only a little coverage to the years 128-113. For the last decade of Hyrcanus's rule, 113-104, he provides much more detail (though the chronology and sequence are distorted).[19] This suggests that the fortress was built before the year 113. In view of the historical circumstances, a date close to the year 125 seems reasonable: the building of the citadel could not have been delayed much longer, since the Akra, the former Hellenistic citadel, was demolished by Simeon around the year 140.[20] The period of peace and economic prosperity after the rise of Alexander Zabinas in Syria in 126 (Ant. XIII.273) provided the resources and breathing space to build a formidable citadel. The year 125 may thus be taken as a tentative post quem date for the composition of Pseudo-Aristeas. This conclusion is supported from another angle: on the basis of the striking similarity between Pseudo-Aristeas 13 and the document at I Maccabees 10.36, it has rightly been suggested that Pseudo-Aristeas was the later of the two.[21] This means that the Letter was composed at least some years after 128.

The year 113 also seems to mark a terminus ante quem for the composition of Pseudo-Aristeas itself. The general atmosphere of peace and affluence that prevails in its description of the country (paras. 100-120)[22] accords with Josephus's evaluation of the middle years of John Hyrcanus's reign (Ant. XIII.273-74). This period came to an end with the invasion of the coastal plain by Antiochus IX Cyzicenus (113) and its reconquest by Hyrcanus (112). This was followed by unremitting wars of expansion pursued by the Hasmonean state beginning in the year 112/11, and the subsequent military interventions of Hellenistic kings in the course of events.

[19] See p. 292 below on the misplaced document in Ant. XIV. 249, which refers to the invasion of the coastal plain by Antiochus IX Cyzicenus, and belongs to the year 113/12; p. 131 nn. 28, 29, on the occupation of Idumea and Samaria (Ant. XIII.254-58); and p. 136 n. 49 on the events surrounding the siege of Samaria and Scythopolis (Ant. XIII.275-83).

[20] On the destruction of the Akra and its date, see Tsafrir (2975 ) 502 and n. 5; Bar-Kochva (1989) 453-54. The source: Jos. Ant. XIII.215-17.

[21] Momigliano (1930) 164-65, (1932) 161-73. Cf. M. Stern (1965) 104-5, (1983) 225; Murray (1967) 338-40. The reservations of Schürer, Vermes, and Millar (1973-86) I.179 and Goodman therein, III.682 and n. 286, are unjustified: the similarity is too striking to be accidental.

[22] This atmosphere has been rightly noticed by Goodman, ibid. III.681.

2. Idumea and Samaria

The same conclusion appears from the passage referring to Idumea and Samaria (para. 107). Bickerman, in one of his inspiring articles, drew attention to this passage long ago and used it as evidence for dating the book between the years 145 and 127.[23] He based his analysis on the traditional assumption that Idumea and central Samaria were conquered by John Hyrcanus around the year 128. The recent excavations in Marisa and Mount Gerizim have, however, definitely proved that Idumea and southern Samaria were occupied only in 112/11 or shortly thereafter.[24] In addition, the chronological implications of the passage on the Jerusalem citadel escaped his notice. A modification of Bicker-man's chronological analysis of the references to Idumea and Samaria and his arguments is therefore required (cf. Maps 3, 5, PP. 118, 126 above).

Pseudo-Aristeas tries to explain why Jerusalem is not a large city.[25] Following the autarkian ideal, he says that the founders were aware of the advantages of a proper dispersion of the population in the rural, agricultural lands, so as to provide the city with adequate supplies. In this context he describes the terrain and agricultural possibilities of the lands belonging to the city (para. 107):

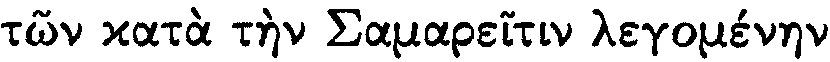

For the country is large and good, and some [of its parts], those in the so-called Samareitis [

][26] and those adjacent to the country of the Idumeans [], are flat. But other [parts] are mountainous, those (in the center of the country. With regard to them it is necessary)[27]

[23] Bickerman (1930) 280ff. See also nn. 33 and 55 below.

[24] See p. 131 nn. 28, 29 above.

[25] For his motive, the inevitable comparison with Alexandria, see p. 110 above.

to attend constantly to agriculture and soil, so that in this way they will also bear much fruit.

The author thus calls the Hebron Hills "the country of the Idumeans." In the time of the First Temple the region belonged without interruption to the Judean kingdom and was inhabited by the tribe of Judah. After the evacuation of the Jewish population with the destruction of the Temple, the region was settled by Idumeans. Consequently it was named Idumea from at least the beginning of the Hellenistic period.[28] In 112/11 it was occupied by John Hyrcanus; its inhabitants were converted to Judaism, and the region was integrated into Judea.[29] The official name of the Hebron region under the Hasmoneans is anybody's guess.[30]

Whatever its name after the occupation was, the author uses the phrase "the country of the Idumeans," which is much more expressive than just "Idumea." A Jewish author living in Alexandria would not have used this phrase in the generation immediately after the

[28] See M. Stern (1968) 226, and esp. Diod. XIX.95, 98, drawing on Hieronymus of Cardia.

[29] Ant . XIII.257; on the date, see p. 131 n. 28 above.

[30] The only piece of information directly relevant to the Hasmonean kingdom is to be found in Ant . XIV.10. However, that statement, which refers to Herod's grandfather, was taken from Nicolaus of Damascus (cf. Ant . XIV.9, >Bell . I.123-24), Herod's court historian. He may well have used terminology from the time of his Idumean Maecenas, when the region naturally acquired a special status. On this status, see M. Stern (1968) 226.

annexation and forced Judaization of the region by John Hyrcanus,[31] when there must still have been considerable sensitivity about the Judaization of the region.[32] An explicit admission that the region was "the country of the Idumeans" would also have caused considerable embarrassment to Egyptian Jews in their confrontations with the Idumean settlers in Egypt.[33] These confrontations produced, some generations earlier, the Idumean version of the notorious ass libel, which was based on, among other things, the ethnographical-religious division between Judea and the Hebron region.[34] Furthermore, if the accepted restoration of the lacuna in the sentence about the mountainous regions is correct (which it almost certainly is),[35] then only the mountainous regions "in the center"—that is, between Jerusalem and the plains "adjacent to the country of the Idumeans" on one side and the plains of "the so-called

[31] On the forced character of the Judaization of the Idumeans, see the recent sensible comment of Shatzman (1990) 58 n. 90; Feldman (1993) 325-26 (pace Kasher [1986] 46-77, 79-85). On the reference in Strabo XVI.2.34, see my note in Anti-Semitism and Idealization of Judaism , chap. VI.6. It is well in line with Posidonius's idealized and fictitious conception of the origo of the Jewish people (Strabo XVI.2.35-36), which was by itself inspired by his political and religious ideals.

[32] Josephus does indeed refer many times to the converted Idumeans as "the Idumeans" in his account of the Great Revolt against the Romans, and at least half the former Idumean territory still preserved the old name, being a toparchy of Judea proper in the time of the Revolt (Bell . III.55; and see M. Stern [1968] 226-29 on the toparchies of Idumea and Engeddi). But the Judaization of the area was by then already an established fact; the Idumeans had proved their loyalty and even extreme zealousness during the Revolt, and there was thus no reason to disguise their ethnic origin. Moreover, it seems quite clear that Josephus wanted to stress their non-Jewish descent and thereby explain their ruthlessness and immoral behavior (e.g., Bell . IV. 232, 310).

[33] Bickerman (1930) 280ff. argued that the expression "land of the Idumeans" proves that the book was written before the occupation of Idumea. In a later version of the article ([1976-80] I.131 n. 93) he changed his mind and noted that the reference has no political but rather a purely geographical connotation, and refrained from using it as evidence for his dating (following Tcherikover [1961a] 317 n.8). Regrettably, he was not aware of the propagandist significance of geographical and administrative designations in the newly independent and expanding Jewish state. A similar policy can be observed in modern Israel, especially after the 1967 war ("Judea and Samaria").

[34] Ap . II.112. On the origin of the story among the Idumean settlers in Egypt, see M. Stern (2974-84) I.98.

[35] See n. 27 above.

Samareitis" on the other—are referred to. The Hebron region is thus not counted among the sources of supply for Jerusalem, which means that it did not belong to the Jews. All in all, the passage could not have been written after 112/11, when the region passed into Jewish hands and was integrated into Hasmonean Judea.

Less significant is the exact geographical meaning of the reference to flatlands "adjacent to the country of the Idumeans." These lands may be the valleys of the southern Shephela, the hilly region west of the central mountain range (like the Elah Valley and several smaller ones), adjacent to the Idumean territory. However, it would have taken considerable expertise to be so accurate, and even had the author gone on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem (which is still doubtful),[36] this would not have been enough: after all, not too many modern Israelis have a precise knowledge of the topographical features of the fringe areas of the Judean Hills. It may well have been an "armchair deduction" from the account in I Maccabees of the flight of the Seleucid troops after the battle of Ammaus, on the fringe of the Judean Hills: the Seleucid troops, who camped "near Ammaus, in the land of the plain" (3.40), are said to have fled after the battle to the "plain" (4.14), and then to have been pursued up to the "plains of Idumea, Ashdod, and Jabneh" (4.15). Pseudo-Aristeas evidently utilized and interpreted for his own purposes certain other minor details found in I Maccabees.[37]

The reference to Samaria is a bit more complicated. Part of the fertile flatlands belonging to the Jews is said to be in "the so-called Samareitis." The chronological conclusion from the reference to the "country of the Idumeans" does not allow us to interpret the sentence as referring to the situation after 112/11, when southern Samaria was occupied by John Hyrcanus—and certainly not after the conquest of northern Samaria and the Great Valley in the year 107. The possibility of identifying these plains with the internal valleys of central Samaria or the Jezreel Valley has therefore to be discounted. Bickerman's suggestion that the author had in mind the three toparchies in southern Samaria (Aphairema, Lydda, Ramathaim), attached to Judea in 145 (I Macc. 10.30, 38; 11.34), remains the only possible solution. Bickerman has also pointed out that Lod, one of the toparchies, is indeed flat.[38] As a matter of fact, one would

[36] See pp. 272, 275.

[37] See p. 278 and n. 21 above. Cf. next paragraph.

[38] Bickerman (1976-80) I.130-31.

not expect the author to have known this. He may well have believed, on the basis of their mention in two royal documents in I Maccabees, that all three toparchies were (or had) fertile plains. The attachment of the three Samaritan toparchies to Judea by the Seleucid kings is listed in two documents among many other economic concessions and grants (I Macc. 10.38, 11.34), a fact that by itself could have led to the conclusion that they were especially fertile. Moreover, the second document even declares remission of taxes on the "produce of the soil and fruit trees" for the annexed toparchies alone (11.34).[39] As "produce of the soil" in this context is certainly wheat, Pseudo-Aristeas could have deduced that the three toparchies were flat. His thorough reading of the documents need not surprise us, given that he could reshape and integrate a single piece of information from the first document (10.36), elsewhere in the course of his narrative (para. 13).[40]

The passage indicates that the three toparchies were still popularly named "the Samarias" or the like: hence, probably, the expression "in the so-called Samareitis,"[41] and not just "in Samareitis." The phenomenon of the preservation in colloquial usage of a former administrative designation or place name some generations after an official change has taken place is well known in the geographical history of the Holy Land. This was often done out of habit or was meant to call attention to the history of a region or locality. In contrast to what was said above about "the country of the Idumeans," there need not have been any ideological or practical reservation against applying the name "Samaria" in this case: it was, after all, one of the two traditional biblical names of the region (the other being Mount Ephraim), and the area of the three toparchies traditionally belonged to the northern Israelite kingdom and the northern tribes.

It is worth stressing that the absence of any reference to agricultural lands belonging to the Jews on the coastal plain does not necessitate a dating before the occupations of Jaffa and the corridor to the sea by Simeon and several of the coastal cities by John Hyrcanus.[42] The

[39] In the first document (I Macc. 10.30), the concession refers to the whole territory of Judea, together with the three toparchies.

[40] See p. 278 and n. 21 above.

[41] On the ending -itis for Samaria, cf. Pseudo-Hecataeus ap . Jos. Ap . II.43; and see p. 114 n. 189 above.

[42] For the date of these occupations, see pp. 124-27 above and 292 below.

author does not refer to the Jericho Valley either, which had been included in the boundaries of Judea since the Restoration.[43] This flat land on the eastern side of the Judean Hills was considerably larger than the "corridor," and its fertility and unique flora were celebrated by Hellenistic historians and geographers.[44] It thus appears that for one reason or another connected with the special context and purpose of the account,[45] the author restricted himself to the mountain range (and its internal valleys).

3. Further Considerations

In seeking a terminus ante quem it should be added that the description of the High Priest in the Letter does not mention any characteristic features or symbols of kingship, and that such an omission excludes the period after the year 104, when the Hasmoneans assumed the throne.[46] Another consideration points to almost the same date: Pseudo-Aristeas describes Gaza as an active and flourishing port serving the commerce of Jerusalem and its vicinity (para. 115). This would not have been written after the siege and destruction of Gaza by Alexander Jannaeus

[43] See Ezek. 2.34, Neh. 7.35, I Macc. 9.50; Jos. Ant . XIV. 91, Bell . III.55-56; Plin. NH V.70; and esp. E. Stern (1982) 245ff. (also referring to the evidence of the Yehud stamps).

[44] See pp. 109-10 above.

[45] The purpose of the account being to explain why the polis of Jerusalem was rather small, the answer elaborates on the need to devote manpower to cultivating the surrounding agricultural lands (paras. 107-8) for the benefit of the city (para. 111). The Jewish lands in the mountain range were naturally regarded in Hellenistic eyes as the chora of Jerusalem. The new Hasmonean territories on the coastal plain, however, were for years considered to be the chorai of the old Hellenized cities. Whatever their status under the occupation, the author would have found it difficult to include them in an account of the Jerusalem chora . This still does not explain the absence of the Jericho Valley, unless one assumes that the author was misled by its fame in the Hellenistic world to believe Jericho was a polis. My feeling is that there may also be another reason, which applies equally to the flat areas on both sides of the mountain range: inclusion of these celebrated large and fruitful regions in the account would only have highlighted the question that stands at the center of his account—why Jerusalem was not a large city. The author therefore restricted his account to the mountain range, whose produce could not maintain a very large city.

[46] Rightly noted by Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.682 n. 286.

in the years 102-101,[47] nor even after 103, when Jannaeus began to harrass the city consistently (Ant . XIII.334).

The account of the Holy Land and Jerusalem thus indicates a dating between the years 125 and 113. Internal events in Ptolemaic Egypt in those years may provide a more accurate date. The years 125-113 fall in the reign of Ptolemy VIII Physcon (145-116), Cleopatra II (116), and Cleopatra III (116-101). Ptolemy Physcon (Euergetes II) was the most evil of all the Ptolemies, and his period the darkest in Ptolemaic history. It was marked by the long struggle between Ptolemy Physcon and his sister-wife, Cleopatra II, which was accompanied by frequent civil disturbances, excesses, and atrocities. Ptolemy Physcon became notorious for his monstrous appearance and conduct, and for his brutal and ghastly treatment of the royal house (including his seven-year-old son), as well as massacres of the citizens of Alexandria. The scholars and artists of Alexandria, who were the pride of the dynasty, were expelled from Egypt.[48] What is especially significant: the Jewish high commanders of the army, appointed in the time of the sole rule of his brother, Ptolemy VI Philometor (164/3-146), and the Jewish soldiers who gained special importance in the latter's days,[49] sided with Cleopatra II. Consequently, Ptolemy Physcon relentlessly persecuted the Jews of Alexandria (Ap . II.49-56, and possibly III Maccabees). The hostile policy toward the Jews went on, with several interruptions, for more than two decades.[50] Ptolemy Physcon was finally reconciled with Cleopatra II in the year 121,[51] and in the year 118 they jointly issued a comprehensive amnesty decree granting far-reaching concessions and privileges to various sections of the population (SEG XII.548).[52] These developments brought relief to the Jews as well. Cleopatra II regained power after the death of Physcon, in 116, but her abrupt death in the same year brought to the throne her daughter Cleopatra III, niece and

[47] See Extended Notes, n. 3 p. 292.

[48] On the days of Ptolemy Physcon, see Extended Notes, n. 8 p. 299.

[49] For the background and details, see Tcherikover (1957) 19-21, (1961) 275ff.

[50] See Extended Notes, n. 9 p. 300.

[51] For the year 121 (and not 124) as the date of the final reconciliation, see Bevan (1927) 314-15; Otto and Bengtson (1938) 103-9; Fraser (1972) II.218 n. 243.

[52] The edict: SEG XII.548. On this much-discussed philanthropia , see, e.g., Bevan (1927) 315-19; Rostovtzeff (1940) II.878-81; Lenger (1956) 437ff.

second wife of Ptolemy Physcon. The young queen (if not already her mother) restored Jewish officers to supreme command of the army. These officers excercised great influence on her policy.[53]

Now, Pseudo-Aristeas provides an enthusiastic description of Ptolemaic kingship, including its attitude toward intellectuals, and of Ptolemaic-Jewish relations. The author's only reservation is in regard to the maltreatment of the Jews in the generation preceding the time of the story. This is so different from the atmosphere during the long reign of Physcon that it would hardly be expected (even as nostalgia) from an author writing under that king, certainly not. In the turbulent days before the reconciliation of 121 or the amnesty of 118.[54] It can, therefore, be suggested that the book was written between the year 116 (or 118 at the earliest) and approximately the year 113, the end of the period of peace that characterized the middle years of John Hyrcanus's reign.[55]

[53] Ant . XIII.285-87, 349-51, 353-54, based on Strabo; and see in detail pp. 241-44 above.

[54] Some scholars, who accepted Bickerman's dating of Pseudo-Aristeas to the years 145-127, tried to find indications in the book of particular events in the time of Ptolemy Physcon. See Jellicoe (1965/6) 144-50, (1968) 50; Meisner (1973) 43; Collins (1983) 83-84. But see the criticism of Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.683 nn. 287, 289. In addition, their analysis is based on Tcherikover's erroneous reconstruction of the development of relations between Ptolemy Physcon and the Jews, suggesting that after his first years Physcon changed his attitude. (See Extended Notes, n. 9 p. 300.) At the same time, another passage may well be a summary of the situation of Egyptian Jewry, looking back to the recent years of Physcon: "Residence abroad brings contempt upon poor men, and upon the rich, disgrace, as though they were in exile for some wickedness" (para. 249).

To close the discussion it behooves us to allude to two arguments ex silentio raised in the past against a dating of the book after the Maccabean Revolt. It has been pointed out that there is no reference in the book to the religious persecutions by Antiochus Epiphanes, which marked a watershed in Jewish history, and that the book does not offer any response to the anti-Jewish libels that flourished in the Hellenistic world in the aftermath of the religious persecutions.[56]

To begin with the lack of reference to the persecutions, recalling them would have detracted from the purposes of the book. Despite all that has been imputed to this book, Tcherikover's view that the Letter was written for a Jewish and not a gentile audience is most convincing.[57] It was intended first and foremost to legitimize the use of

[56] See, e.g., Jellicoe (1968) 48-49 (quoting H.Z. Orlinsky); Rappaport (1970) 40-41; Goodman in Schüer et al. (1973-86) III.681; and apparently also Fraser (1972) II.970 n. 121.

[57] Tcherikover (1958), and even more decisively in the Hebrew version of the article, (1961a) 316-38. Cf. Cahana (1956) II.6-8. The long and elaborate discussion of Jewish separatism (paras. 128-69), which may look apologetic, was also intended for Jewish readership. The author was aware of the apparent contradiction between his call for adherence to the precepts of the Torah on the one hand, and for the adoption of Greek culture on the other. Jewish dietary laws, which inevitably led to social segregation, could not have been harmonized with certain basic features of Hellenistic culture. The question must have puzzled the moderate reformers in Alexandria. The author's main explanation: the separation was needed in order to protect Jews from being influenced by the pagan and immoral aspects of the surrounding cultures, and thereby to assure their adherence to the enlightened philosophical principles and values of Judaism (paras. 130, 139, 142, 152). A similar complimentary explanation was given about two generations later by Posidonius of Apamea (ap . Strabo XVI.2.35). Nevertheless, the author does not totally prohibit social contacts and participation in Greek symposia. They are even recommended in the case of highly educated and talented personalities who are qualified to present the Jewish case, and determined to reject the negative manifestation of Hellenism. However, it must always be guaranteed that only kosher food is served and that certain pagan table ceremonies are avoided (paras. 181-82, 184).

the Septuagint in religious services, to encourage the adaptation by the Jews of the enlightened features of Greek culture and its achievements, and to promote their use in interpreting Judaism. At the same time the author advocated adhering to Jewish beliefs and religious practices (paras. 127ff.). Hence, among other things, the laborious rationalization of Jewish dietary laws (paras. 124ff.), which at first sight did not coincide with the "Hellenization" advocated by the author Now, the confrontation in the time of Antiochus IV started with the attempt of the Jewish Hellenizers to force their way of life on Jerusalem, and was followed by the religious persecutions instigated by the king. A reference to these traumatic events would only have called attention to the dangers inherent in the process of Hellenization and played into the hands of the "stubborn" Jews, who were said to have turned their backs resolutely on Greek culture (para. 123).[58]

The writing of the book for internal purposes also explains why it does not try to refute the anti-Jewish libels. Jews did not look for arguments to be convinced about their falsehood. The three notorious stories, the leper, the ass, and the blood libels, were so absurd that there was no need for their refutation in a book written for Jews. Similarly, Hebrew literature in the Middle Ages did not offer arguments against the blood libel, despite its recurring horrible consequences. As a matter of fact, even those Jewish Hellenistic authors who may also have written for gentiles are silent on this issue, notably Philo, despite his prolific literary output. Only Josephus, in his polemic Against Apion , bothered to go into detail and undermine the three libels.

Be that as it may, the three libels were not invented after the religious persecutions. Two of them were known in Egypt already at an early stage of the Hellenistic era,[59] and all of them seem to have been inherited in one way or another from Egyptian traditions of the Persian period.[60] The absence of any reference to the libels in any case does not require dating Pseudo-Aristeas before the time of the Hasmonean state.

[58] On these groups among the Jews of Alexandria, see pp. 171, 176-81 above.

[59] See M. Stern (1976) 1111, 1114, 1120.

[60] See my detailed discussion in Anti-Semitism and Idealization of Judaism , chaps. II.2 and III.5.