Formalism

Formalism, whether Beaux-Arts or neo-rationalist, assumes that there are archetypal patterns and configurations with universal significance from which urban design should be drawn. Although the emphases and the socio-economic effects of the two approaches differ dramatically—proponents of Beaux-Arts formalism stressed axial organization and static spaces and, more recently, proponents of neo-rationalist formalism have focused on a finer and more circumstantial urban grain—both points of view assume that urban form is best drawn from timeless patterns. Neo-rationalism is now stronger than Beaux-Arts formalism as an intellectual current, but it has had little impact in America to date because the important Italian treatises of the 1960s that formulated it were not translated for a decade. Further, neo-rationalist theory is strongly related to histori-

cal European urban patterns and therefore is difficult to transpose to American contexts.

Aldo Rossi, a key advocate of neo-rationalism, speaks approvingly of the typical American grid, though he does not indicate what one could do with it or how it might guide and give impetus to contemporary urban form. Rossi speaks approvingly, too, of American towns with what might be called a late-medieval character, towns like Boston and Nantucket. But again, Rossi does not indicate how these models could inform new urban patterns. The scale of building in Manhattan impressed Rossi, but should other American cities seek to achieve the character of Manhattan? Because neo-rationalism has had little impact to date, the study of formalist efforts in American cities must focus on Beaux-Arts City Beautiful schemes. But we are convinced that the points we make here about earlier Beaux-Arts formalism will apply when neo-rationalist formalism appears in American streets: it will fail to blossom because it too is narrow and alien.

The Vision of Civic Axis

The grandest plan to put Beaux-Arts formalism into practice in Milwaukee envisioned a civic axis rising at a domed county courthouse. A broad avenue would unfold between flanking gardens and then pause at a rond point braced by four buildings of civic significance. Finally the axis

25.

A drawing suggesting Alfred C. Clas's scheme for a Milwaukee Civic Center.

26.

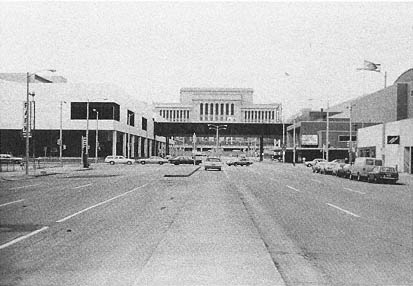

Milwaukee County Courthouse seen down the "civic axis" of Kilbourn Avenue.

Buildings along the axis have not been sympathetic to the concept. The bridge

connecting the convention center and auditorium indicates how little the idea of

a civic axis meant to a subsequent generation.

would cross the Milwaukee River and terminate at the portals of the pre-existing muscular City Hall. Of this grand but feasible vision (after all, San Francisco had managed to build the beginnings of such a dream), only a courthouse (and then not a domed one) was built.

Milwaukee made a second effort to achieve a monumental civic axis, with the County Courthouse as an anchor for Kilbourn Avenue, which extended toward City Hall but angled off to miss that monument and passed on to terminate at the bluff above Lake Michigan. Civic buildings and other edifices of substance were to line this grand avenue. This second effort, however, akin to Edmund Bacon's idea for a "shaft of space" (outlined in The Design of Cities ), either was too grand for the city's civic and financial resources or, perhaps, was begun too late. The Beaux-Arts inspired City Beautiful movement, which sought to link American cities to the archetypal grandeur of European capitals, was losing potency in America at the time the construction of the Milwaukee County Courthouse was completed. Few of the structures built along Kilbourn Avenue fulfilled the original magnificent idea, and what has been built for the most part does not reinforce the sense of a civic axis. The Performing Arts Center, for example, although it was built on Kilbourn Avenue, does not front that axis but rather a minor, competing axis, the Milwaukee River. Kilbourn Avenue was simply too long; Milwaukee did not have enough civic energy to realize the conception. This was another case where the imported vision did not suit the realities.

The Vision of Public Realm

The shared, public, realm of a city often takes the shape of public squares or patches of nature in the city. Neither archetype seems to have inspired design decisions in Milwaukee when in recent years a new riverside park was created downtown. At best Pere Marquette Park is an amenity offering places to sit and stroll, but it is a compromise. It is neither an urban square nor an area given over to another, un-urban, world of nature. It does not pull parts of the city together; instead it does little more than occupy a landscaped area between other, unrelated, areas. Suburban lawns seem to have inspired it. Like so many other efforts to do something in downtown Milwaukee, this one lacked both conviction and a vivid guiding vision.

Elsewhere downtown the redevelopment of formal green squares, like Cathedral Square and Zeidler Park, has accentuated neither their urban nor their natural character. They have none of the suggestiveness of an eighteenth-century London square, for example, or a lush Victorian urban garden. These efforts failed not for having roots in European theory but for having no roots at all.

27.

Pere Marquette Park, situated downtown on the Milwaukee River, which was

once used for commerce, commemorates the landing of the missionary-explorer

Father Marquette. The site is prime in every way. It marks the important historical

process of exploration. It faces the Performing Arts Center across the river and

has frontage along the Kilbourn Avenue civic axis. It offers diagonal views of

downtown and of Milwaukee's striking City Hall. It is a crossroads for civic,

commercial, industrial, and sporting Milwaukee as well as a gateway to North

Third Street, with its Victorian buildings. The rich, strategic, and meaningful nature

of the site was ignored or suppressed, however, in a design that features a

suburban lawn, a curving walk, and some standard benches.

28.

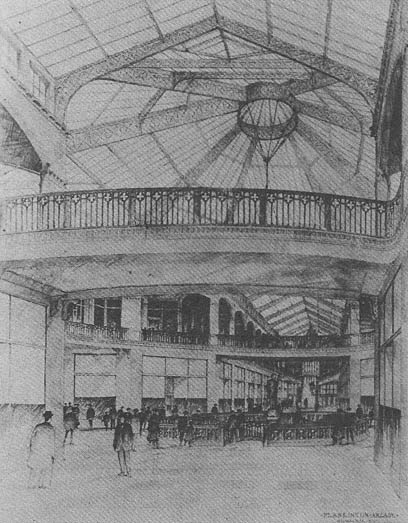

Interior, Plankinton Arcade. Holabird and Roche, architects, Chicago, 1916.

Bridges and dome highlight the intersection of the building's axes.

The longer one parallels Wisconsin Avenue.

The Vision of Galleria

The Plankinton Arcade was Milwaukee's version of a classic urban element, the spacious skylighted semipublic commercial interior whose precedents range from Milan's Galleria and London's Burlington Arcade to more modest manifestations in Cleveland and Providence. Once a lively place, the Plankinton Arcade was allowed to age and decline. For more than sixty years it remained an isolated good idea, with no influence on its context. No one seems to have been inspired enough by it to

copy or improve upon it or to link up with it—not, that is, until the mid-1970s.