III—

The Ascent of the South Peak

That I might see its heavy waves over the glittering ocean, as they chant a melody to their Father on their eternal course.

Anonymous Irish author, twelfth century

Our curiosity about the South Peak was aroused by Lord Dunraven's description of the ruins of an oratory on one of its highest terraces and by Gillan's plan of that terrace. For generations the South Peak had been the object of a famous pilgrimage climb; to reach the end of the Spit and there kiss the upright stone required alpine skills and cool audacity. But who had built this oratory—and for what reason? If it had been built by pilgrims or for pilgrims, why had it never been mentioned in earlier accounts of the pilgrims' climb?

We decided to find an answer to this question. For six summers, whenever the weather and a hiatus in work on the monastery of Skellig Michael permitted, we hoisted ourselves up the South Peak, laden with mountain-climbing and surveying equipment, cameras, and notebooks, to examine, measure, and record. We hope that this study stimulates a thorough archaeological examination.

For what we found—as puzzlement gave way to conjecture—appears to be the remains of one of the most daring architectural expressions of early Irish monasticism: a hermitage built virtually in the air on the treacherous ledges of an Atlantic rock rising straight up from the ocean to an altitude of 218 meters. Level surfaces on which to build the structures necessary for a hermitage did not exist. They had to be created—and were created—by the erection of walls at the brink of steeply slanting ledges, along the very boundary between life and death. These walls could have been built only by men who believed that every stone they laid brought them one step closer to God. By building a hermitage at the top of the island, they reached the ultimate goal of eremitic seclusion—a place as near to God as the physical environment would permit.

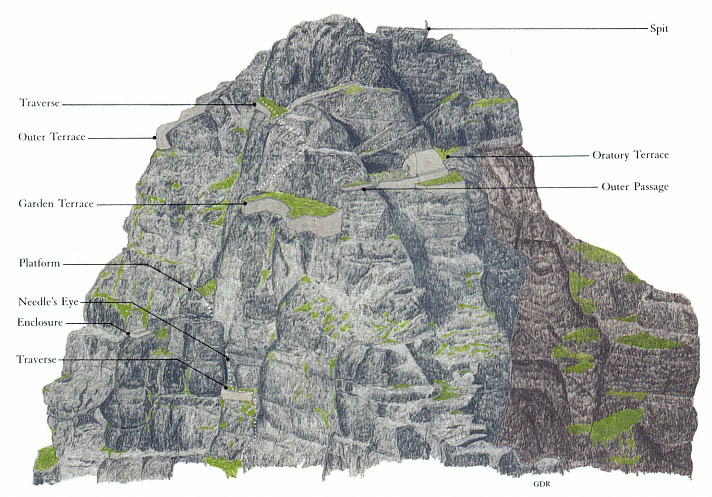

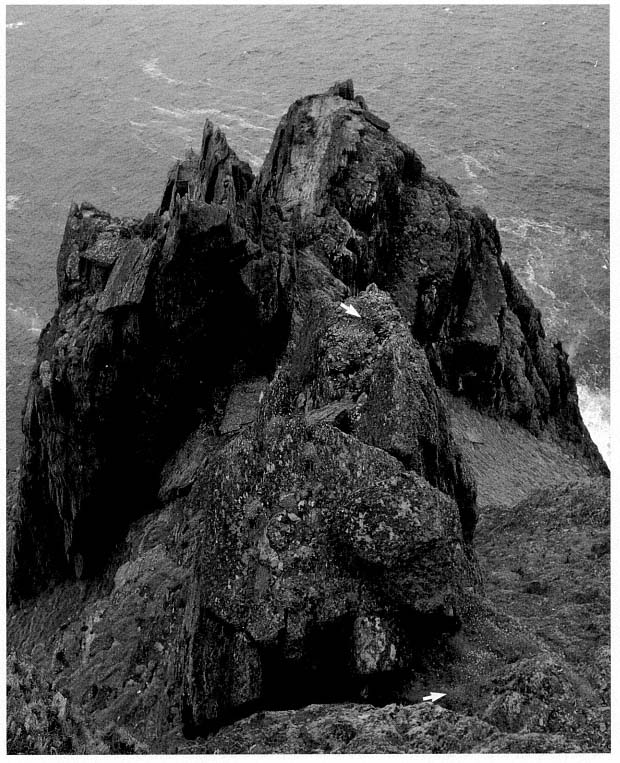

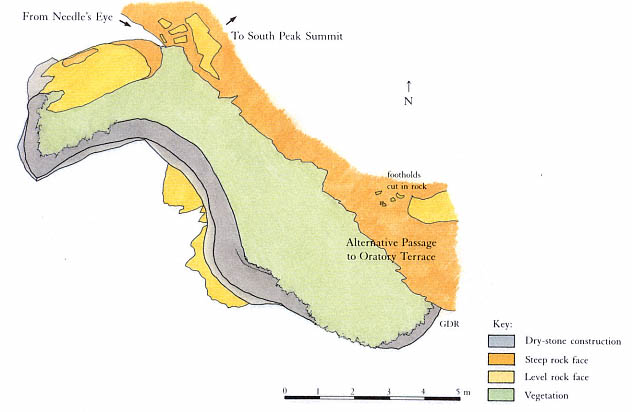

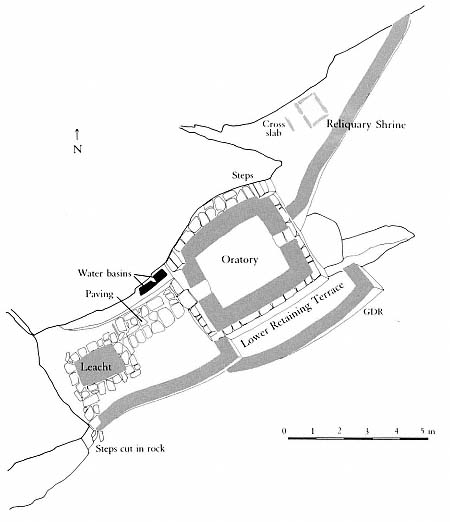

The hermitage consists of three separate terraces that we have tentatively labeled oratory terrace, garden terrace, and outer terrace. Figure 12, a reconstruction drawing, and Figure 13, an aerial view, show the topographical locations of these different terraces; the dotted line on the drawing shows the trail that connects them. The garden and oratory terraces are located near each other, on the two best natural ledges on the peak. Their spatial proximity was reinforced by the construction of two passages between them, suggesting that they had an important functional relation. The outer terrace, in contrast, is set very much apart from the oratory and garden terraces and is also the most difficult to reach.

Fig. 12

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Rendering of the man-made terraces and buildings. The dotted line shows

the visible portions of the route to the summit.

Drawing by Grellan Rourke.

Accounts of the ascent preceding Lord Dunraven's give no reason to believe that the pilgrims of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries knew of a hermitage on the South Peak. We can surmise that either the structures had deteriorated so as to be unrecognizable as structures or the pilgrims considered them uninteresting. Certainly by the mid-nineteenth century they must have been in poor condition, for neither the 1841 map nor Lord Dunraven's account, based on his visit in the late 1860s, connects the remnants of stone construction with the possible existence of a hermitage.

The first-time visitor, climbing the rock for penance or simply for adventure, finds the ascent itself too exacting and exciting to allow any interest in archaeological exploration. Even for our company of determined investigators, the topographical puzzle of the South Peak's religious stations began to unravel only after our fourth or fifth visit and after we had made a careful photographic survey of the peak from the air. As we became familiar with the area, we found that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century accounts had exag-

Fig. 13

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Aerial view of the peak from the south, showing (near bottom left) the Needle's Eye, (above it to

the right) the garden terrace and the oratory terrace on their respective levels, and (to the left of the other terraces) the wall of

the outer terrace.

Photograph by Walter Horn. (See Fig. 8 for a view of the entire island from the south.)

gerated the dangers of the climb. Wherever possible, the builders of the trail to the top of the peak had aided the ascent by constructing dry-stone traverses and masonry steps or, in the steeper places where such construction was not possible, by cutting toeholds and handgrips in the rock face.

But only a climber with a good head for heights and reasonable physical agility should ever try the ascent, and no one should attempt it when the ground is wet or when gusting winds lash the island. In the more precipitous passages the danger is immediately visible, but elsewhere the hazards are less obvious. In several places along the trail, the ledges were improved with masonry additions, and massive masonry bridges were constructed across impassable gullies. Now after a thousand years, however, much of this masonry work is slipping away (see, for example, the masonry traverse leading to the Needle's Eye, visible in Fig. 18, where the badly subsided masonry is unpredictable and must be approached with extreme caution).

From Christ's Saddle to the Needle's Eye

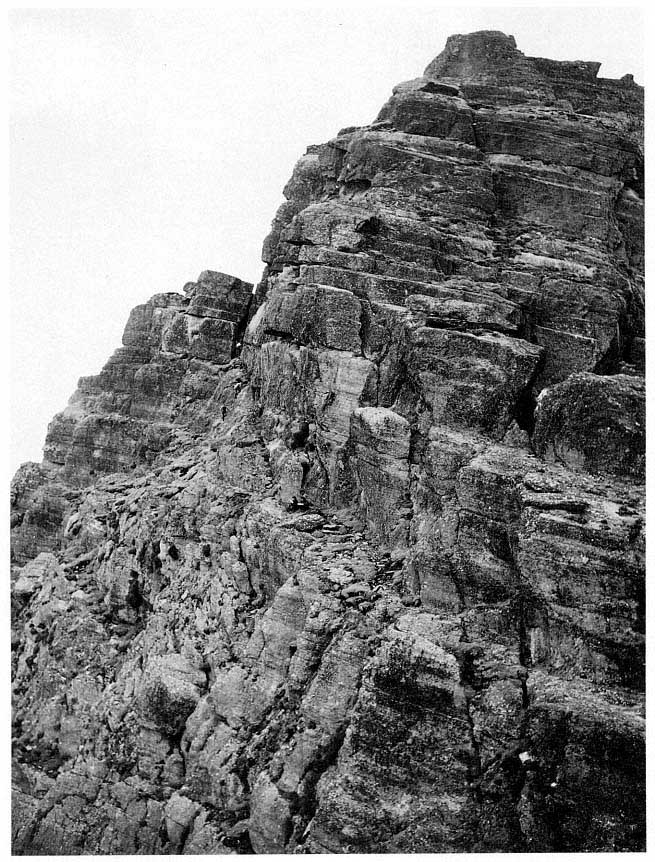

From the lowest point of Christ's Saddle a green slope rises to the narrow ridge connecting the South Peak with a massive outcropping of rocks to the south (Fig. 14). At the northern end of that ridge, at its very juncture with the South Peak, the ascent to the summit begins. A short, steep cleft containing remains of masonry steps leads to a natural ledge that spirals around the western face of the peak (Fig. 15).

Fig. 14

Skellig Michael. Christ's Saddle, western slope. The footpath leads to the starting

point of the trail to the Needle's Eye. Figure 10 shows this same slope from a

perspective that includes the South Peak (note the rocks at center right here,

also visible at lower left in Fig. 10). The steps in the foreground climb from Christ's

Saddle to the monastery (Map 2 shows the location of the island's stairways).

Near the lower part of the trail to the South Peak is a cavelike shelter (arrow)

that may have been used as a penitential retreat or temporary hermitage by

the Skellig monks. A cross is engraved on the rock at the entry to the shelter.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 15

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Natural ledge of rock curving around the South Peak to the Needle's Eye

(dotted line marks the path).

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Initially, passage is comfortable and easy along the broad trail (Fig. 16). After some forty meters, however, the ledge becomes steep, narrows to half a meter, and turns a blind corner (Fig. 17). Notwithstanding the steps cut into the rock face at the turn, no one with vertigo would attempt to negotiate this intimidating corner, where the drop-off is seventy meters. From the path one can see an awesome natural formation on an adjacent crag that one is tempted to interpret as a station of the cross. After the blind corner, the path

Fig. 16

Skellig Michael, South Peak.

Steps cut into the rock ledge on

the path to the Needle's Eye.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 17

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Blind corner (at the top of the steps) in the path to the

Needle's Eye. Note the crag at left, which is visible in Figure 8 as a point of rock to

the left of and below the summit.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

levels out once more and broadens before ending at the foot of a massive rock. At the top of this rock is the formation that has become famous in the legend of the South Peak: the Needle's Eye.

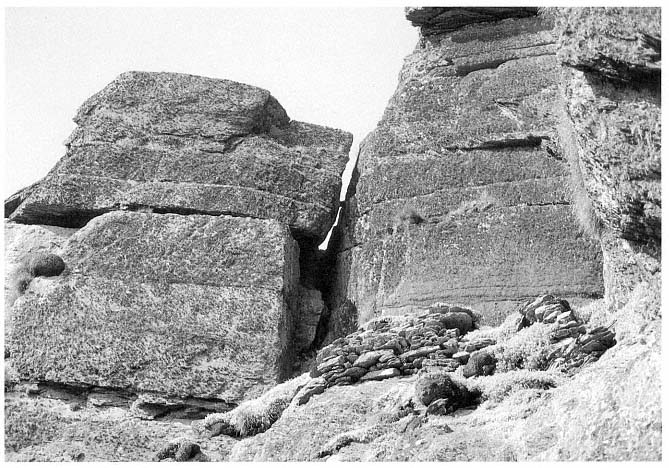

The Needle's Eye

The Needle's Eye (Fig. 18), the gate to the upper part of the peak, is a narrow rock chimney formed by a vertical crack in the massive block projecting horizontally from the principal body of the peak. The entrance to the chimney, some five meters above the path, is reached by climbing a rock face on which steps have been cut deeply enough to serve as toeholds, none of which, however, accommodates an entire foot. A dry-stone traverse about four meters long and one meter wide was built to provide level access to the base of the Needle's Eye.[1] Beautifully constructed and vital for a safe passage, it is now untrustworthy.

Fig. 18

Skellig Michael, South Peak. The Needle's Eye. Its entrance is reached by a short traverse of dry-stone masonry at the

top of a steep rock face. The masonry has deteriorated, bulging and subsiding dangerously.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

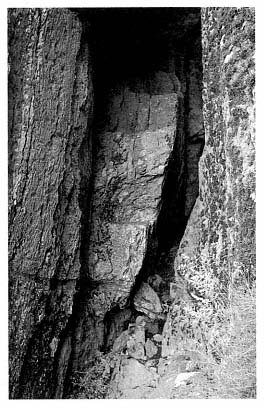

The ascent through the high narrow shaft of the Needle's Eye is aided by well-defined natural spurs and fissures as well as by chiseled grips for feet and fingers on the side walls and on a central rock running up the chim-

[1] The depth of the fill on the traverse varies from .70 meter to 2 meters. Eight masonry steps, each .64 meter wide and curving slightly to the left, were built into the traverse at the southwest end to permit access from the rock face to the top of the traverse. Construction of this rather wide, level access may have been necessary to facilitate transportation and temporary storage of building materials and supplies here.

ney (Fig. 19). Climbers must hoist themselves up seven meters, alternately lifting the body and then bracing it against the chimney walls while searching for the next support. Without these supports, climbers would require acrobatic skills to inch up the shaft. Even now it is not easy because the distance from the first to the second step is over a meter. The passage is especially difficult on the downward journey.

Fig. 19

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Entry to the

Needle's Eye. Footholds are cut into a

vertical rock in the center of the chimney.

The chimney itself varies in width from

half a meter to a meter.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

From the Needle's Eye to the Hermit's Garden

Climbing is easier near the top of the chimney where the central rock develops into well-defined steps (Fig. 20). The climber stepping out of the Needle's Eye discovers the first of several perplexing structures on the South Peak. Two crescent-shaped masonry platforms (see Fig. 57) were built here, one slightly higher than the other, that have no connection with the climb to the top. Possibly the monks used them as construction platforms, level areas on which to pile building materials brought up the chimney by rope.[2]

Fig. 20

Skellig Michael, South Peak. The Needle's Eye.

View down the shaft from the last of the four

steps cut into the inner wall of the chimney

above the spine of rock shown in Figure 19.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

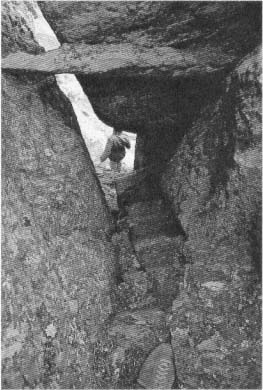

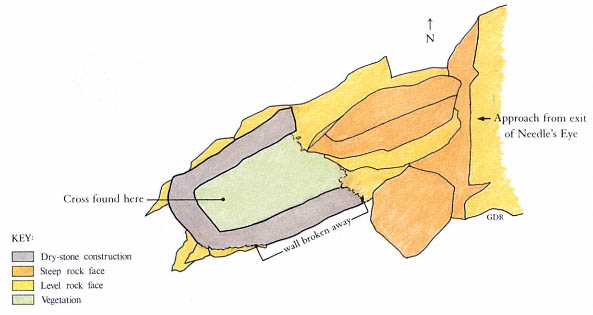

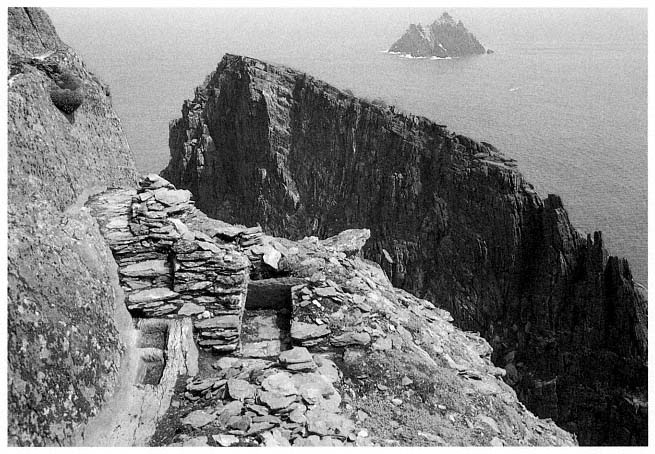

The remains of another odd structure lie nearby, separated from the trail leading to the top and visible only from above. On the far side of the Needle's Eye are the remains of a small U-shaped enclosure built on a level spur facing west to the sea (Fig. 21). Access is awkward, requiring a scramble up and over the large rock that is the west side of the Needle's Eye. This time no helpful handholds or toeholds mark the way.

[2] After negotiating the chimney, the climber steps onto the lower of these platforms (not visible in photographs), which extends almost 4 meters. Up three rock-cut steps is the second platform, which runs for 7 meters, ending abruptly at a rock face. Another possible reason for their construction may have been the need for access to areas for bird hunting on the north side of the peak.

Fig. 21

Skellig Michael, South Peak. The rectangular masonry enclosure (upper arrow) at the outer edge of the

Needle's Eye. The exit from the Needle's Eye is at the lower arrow, and in the background, at left,

are the ruins of the Upper Lighthouse.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

The inside of the enclosure is about 2.3 meters long and 1.2 meters wide; the wall varies in thickness from .35 to .50 meter (Fig. 22). Although the enclosure wall now is rather low, with stone rubble filling the interior, it is still possible to trace both the inside and the outside except at the entry and externally at the southwestern corner, where it has fallen away. The masonry, of fairly small-sized stones, is difficult to judge, but the scale and technique of construction are those of a rectilinear enclosure wall, not those of the base of a cell. Judging from the amount of fallen stone and taking into consideration stone that has fallen over the edge, we calculate that the original wall may have been from 1 meter to 1.5 meters high.

Fig. 22

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Drawing by Grellan Rourke of the small enclosure near the Needle's

Eye, based on the 1986 survey of the hermitage by Grellan Rourke and Richard Stapleton.

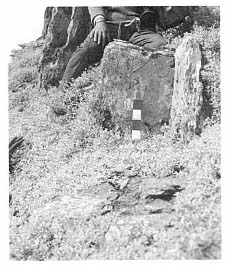

A short length of wax candle and a fragment of a rude stone cross, identical to crosses in the monastery graveyard, lay under collapsed stone in the enclosure (Fig. 23). Was this a place for a hermit to pray and meditate?

Fig. 23

Skellig Michael, South Peak.

Fragment of a cross found in the

small enclosure.

Drawing by Grellan Rourke.

After the detour to the enclosure, the climber returns to the trail above the Needle's Eye and continues to ascend, making a sharp turn to the right. The next task is scaling a rough-textured rock gully nearly fifteen meters high (see Figs. 12, 13). Here again progress is aided by toeholds, although these are not always easy to recognize because plants, also seeking a foothold on the irregular surface, fill the crevices of the gully.

At the top of the gully the climber finds, in a narrow rock cleft (Fig. 24), masonry steps that lead to the first and lowest of the three hermitage stations, one that has never before been recognized and is nowhere mentioned in the accounts of previous visitors to the site (Fig. 25).[3] The reason for this omission is simple: the climber stepping onto this terrace with surprise and relief cannot see that it has been constructed. The walls holding the terrace in place, invisible to anyone ascending the gully to the terrace or standing on it, can be seen only if one leans far over the edge, something few visitors would think of doing.

[3] The cleft has been artificially widened; at least .5 square meter was removed (presumably by the monks) from the western, entrance, side to facilitate access to the terrace (O'Sullivan 1987).

Fig. 24

Skellig Michael, South Peak. The garden terrace from above. The narrow rock

cleft that provides access to the terrace is at the lower right. Paddy O'Leary (top),

secured by a rope held by Lee Snodgrass, examines the retaining wall.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 25

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Aerial view of the garden terrace. Photograph taken in 1987 by Con Brogan.

Courtesy Office of Public Works. Dotted lines indicate the two passages to the oratory terrace, the upper

one over the hump of rock that separates the two terraces, the lower one around its outer face.

Fig. 26

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Plan of the garden terrace by Grellan Rourke, based on the plane-table survey of 1986

made by John O'Brien and Grellan Rourke, assisted by Aidan Forde of the Kerry Mountain Rescue Team.

Fig. 27

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Garden terrace. Northwestern end of the retaining wall built on a solid ledge of bedrock

and therefore still in excellent condition.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

The Garden Terrace

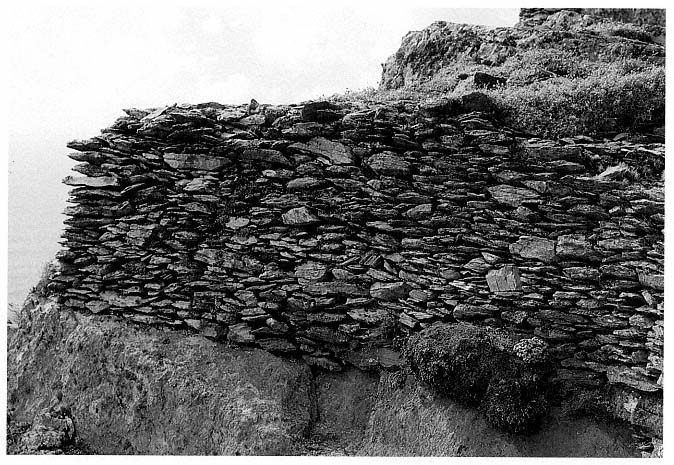

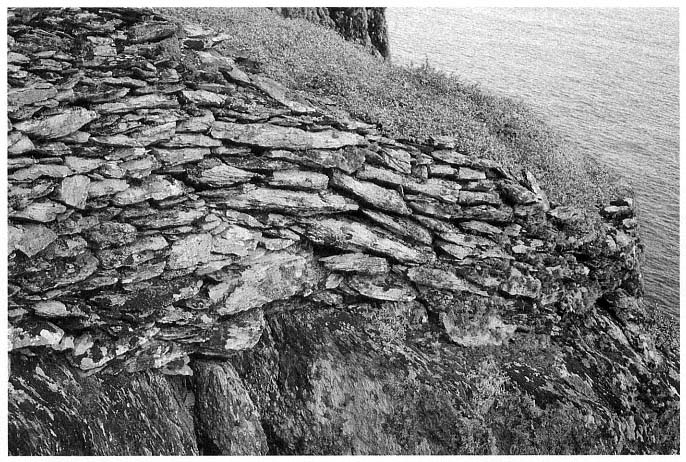

During our first two visits we too were unaware that we were standing on a man-made terrace. On our third visit, we leaned over the edge and took the photographs shown in Figures 27 and 28. In 1982, Paddy O'Leary and Lee Snodgrass measured the platform; later, in 1986, Grellan Rourke made the plan shown in Figure 26.

The kidney-shaped terrace is thirteen meters long and varies in width from two to four meters. The long axis of the terrace runs roughly from northwest to southeast. The retaining wall, 1.5 meters high at the northwestern end of the platform, is built on firm bedrock (Fig. 27). This section of the wall is in impeccable condition, as solid as when first constructed. It is identical in style with the best dry-stone masonry found in the monastery itself (see Fig. 33). Toward the southeastern end of the platform the height of the retaining wall decreases in places to as little as .3 meter (Fig. 28). Here the courses are no longer horizontal but jumbled, an effect characteristic of subsidence, doubtless caused by their construction on the section of the ledge that tilts briskly southeastward. At present there is a drop of 2.4 meters between the northwestern and the southeastern ends of the terrace; estimates based on

Fig. 28

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Garden terrace. Southeastern end of the retaining wall where the masonry has slipped,

greatly lowering the level of the terrace.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

this drop suggest that at least 40 percent of the original terrace fill is no longer there. The southeastern section of the wall, now only .3 meter high, would have needed to be approximately 3 meters high to create a level terrace.[4] The original terrace wall was probably never more than a meter above the present level of the northwestern section, as the walls are too thin and roughly constructed on the inner face to have supported a greater height.

Although we call this platform the garden terrace, its function is open to speculation. A masonry traverse or passage was not needed for the climb to higher terraces or to the summit. In fact, the path continues upward just at the point of access to the terrace in an unbroken line of solid rock (see the upper passage indicated on Fig. 25). Furthermore, there are no definite remains or other visible evidence that any structures were ever built on this platform. There is, therefore, no immediately apparent reason for its creation. The possibility that it was built to provide space for a garden warrants further discussion.

The lowest platform is by far the best place on the South Peak for a garden. Its northwest-to-southeast axis gives it full exposure to sunlight from late morning to evening. At the northwestern end of the terrace the wall is only about half a meter wide, with a ragged inner face composed of stones smaller than those on its smooth outer face—an indication that the inner face was never meant to be seen, at least at this level. Moreover, the soil on this terrace, unlike the typically heavy, wet soil of the South Peak, is light and dry, thus ensuring good drainage. Scattered throughout the soil are thousands of small sharply faceted stones that are clearly detritus, fragments of quarried rock. Much of this stone fill is from rocks not indigenous to the South Peak. In addition, there are some sandstone cobbles that may have come from Seal Cove or Cross Cove (see Map 2).[5] Clearly, a considerable amount of the fill for this terrace was brought up the peak. Neither here nor in the monastery gardens is there evidence of an irrigation system; evidently rainfall provided sufficient moisture to raise plants in this climate.

Because agricultural work was a necessary part of a monk's responsibility, important for the health of both body and soul, gardens were an integral part of monastic life. Vegetables, furthermore, are often mentioned in the literature as an essential part of the monastic diet. Some austere diets, like that of the Bangor monks under the rule of Abbot Comgall, consisted of vegetables supplemented with bread.[6] The diet of island monks, however, differed somewhat from that of mainland monks. The staples of Irish monks living on the North Atlantic islands from Ireland to Iceland were, of necessity, fish and the meat and eggs of the birds nesting on these islands.[7] Grain for bread was not easily obtainable, as it required more growing space than most islands possessed. Therefore vegetables were particularly important as a dietary supplement. Striking evidence of the importance of monastic gardens can be seen in the extensive terraces that served as gardens for the monastery of Skellig Michael (see Fig. 9).

A garden, moreover, would have spiritual importance to a hermit because it would help him to maintain his solitude and independence from the

[4] Rourke estimates that such a wall could have retained approximately 45 cubic meters of fill; 14 cubic meters have fallen away, so that only about 31 cubic meters are now being retained. Michael O'Sullivan (1987) cautions that the distribution of the underlying bedrock is unknown, and therefore these figures must be considered maximal, for they assume that the bedrock profile is relatively planar.

[5] This is the opinion of O'Sullivan (1987), who notes in addition the possibility that the sandstone cobbles on the terrace, much smaller than those found in Skellig coves, may have been brought from the mainland.

[6] Vitae Sanctorum Hiberniae , ed. Plummer, 1910, 2:13.

[7] There is no literary evidence to attest that sea birds were an integral part of the diet of the monks of Skellig Michael, but Michael O'Kelly, excavating nearby Church Island, found that the monastic inhabitants had eaten gannet, shag, cormorant, white-fronted goose, and duck (O'Kelly 1958, 130). Bird eating is common among secular inhabitants of the Atlantic islands. For the old St. Kildan tradition of eating birds and birds' eggs, see Martin, A Voyage to St. Kilda , 1698; Macaulay, The Story of St. Kilda , 1764; Maclean, Island on the Edge of the World , 1980. For a general discussion of the birds that breed on the Skellig rocks, see Des Lavelle, 1977, 68–83.

monastery. In the seventh century St. Cuthbert, abbot of Lindisfarne, retired to Farne Island to live a life of eremitical solitude. The tiny island, with no water, no food, and no trees, was perfect for an ascetic monk. St. Cuthbert's monks helped him to establish his hermitage, building an enclosure wall, carving a well out of rock, and constructing "such essential buildings as an oratory and a communal shelter [that is, one for domestic use]." St. Cuthbert then ordered his monks to bring him gardening utensils and seed, for he intended to live an independent life: "If God's grace will enable me to live in this place by the labour of my own hands, I shall gladly remain there; but if it proves otherwise, then, God willing, I will soon return to you."[8]

From the Garden Terrace to the Oratory Terrace

The second and most important of the three eremitic stations of the South Peak, the oratory terrace, lies at right angles to the garden terrace four meters above it, with a rock barrier separating the two terraces both physically and visually. There are two ways to travel from the garden to the oratory terrace. The most obvious and safest way is to continue the climb to the summit from the northwestern end of the terrace, on a series of steps cut into the rock. The steps lead to the top of the long rock ridge separating the garden and oratory terraces. At the top of the ridge a left turn (to the northwest) leads to the final ascent to the summit, and a right turn leads down to the oratory terrace (Fig. 29).

Fig. 29

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Oratory terrace. Aerial view from the southeast,

showing the surviving walls of the oratory and, on the collapsed outer section of

the terrace, the remaining masonry fragments of the retaining wall. Dotted lines

mark the two approaches to the oratory terrace from the garden terrace, the upper

one over the hump of rock between them, the lower one around its outer edge.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

[8] Bede, A History of the English Church and People , trans. Sherley-Price, 1955, 261–62. For the Latin see Two Lives of St. Cuthbert , ed. and trans. Colgrave, 1940. As late as 1084 the charters of Kells mention a permanent disert , "hermitage," with a garden for wandering hermits: "These ¦charters of Kells¦ have all granted for ever Disert-Columcille in Kells, with its vegetable garden, to God and devout pilgrims , no wanderer having any lawful possession in it at any time until he surrender his life to God, and is devout" (Adamnan, 1874, cxxv; italics in original).

Originally another connection led from the southeastern end of the garden to the oratory terrace, up steps that are now barely discernible in the rock face and along the outer edge of the ridge between the two terraces. The existence of this outer passage is further evidenced by the dry-stone masonry buttressing a large slab on this ledge.[9] Fragments of the masonry can be seen only from the air or through binoculars from lower levels of the island (see Fig. 25). At the far end of the ledge, precipitous steps cut into the ridge led down to the retaining wall of the oratory terrace (at the end of the outer passage shown in Fig. 29). The passage, a shortcut between the two terraces, is dangerous in windy or wet weather, particularly at the narrow juncture with the oratory terrace, where the retaining wall no longer exists. Because of the danger of this juncture, we conclude that the passage was built after the construction of the retaining wall for the oratory terrace.

Fig. 30

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Oratory terrace, looking east, before the clearing of the sea campion. At left, the surviving

parts of the north and west walls of the oratory; beyond the terrace, the slanting surface of the monastery summit of

Skellig Michael. Only the domes of two beehive huts and an oratory are visible from this angle. Little Skellig and the

mountains of the Ring of Kerry are visible beyond the monastery.

Photograph by Jenny White Marshall.

[9] The outer passage varies in width between .6 meter and 1.5 meters.

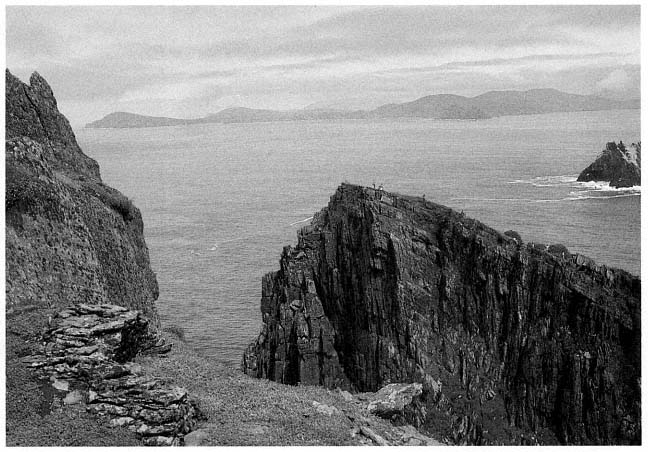

The Oratory Terrace

This station, lying about two hundred meters above the ocean and some fifteen meters below the summit, offers a magnificent view of the seascape east of the island (Figs. 30, 31). Until we cleared away the sea campion, it flourished, almost covering the remains of two walls of the oratory. Beyond the terrace, on the other side of Christ's Saddle, the domes of the monastery's beehive cells are seen on the northeastern summit, with the dramatic silhouette of Little Skellig rising behind. In the background, the delicate curve of the mountains of the Iveragh Peninsula, more than eleven kilometers to the east, frames the seascape.

Over time, the oratory terrace has suffered so severely from the collapse of its retaining walls that it is perilous to examine, and its original

Fig. 31

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Oratory terrace, with the west wall of the oratory freed from its overgrowth of sea

campion, revealing a flagged path and steps descending to the water basins on the north side of the oratory.

Photograph by Jenny White Marshall.

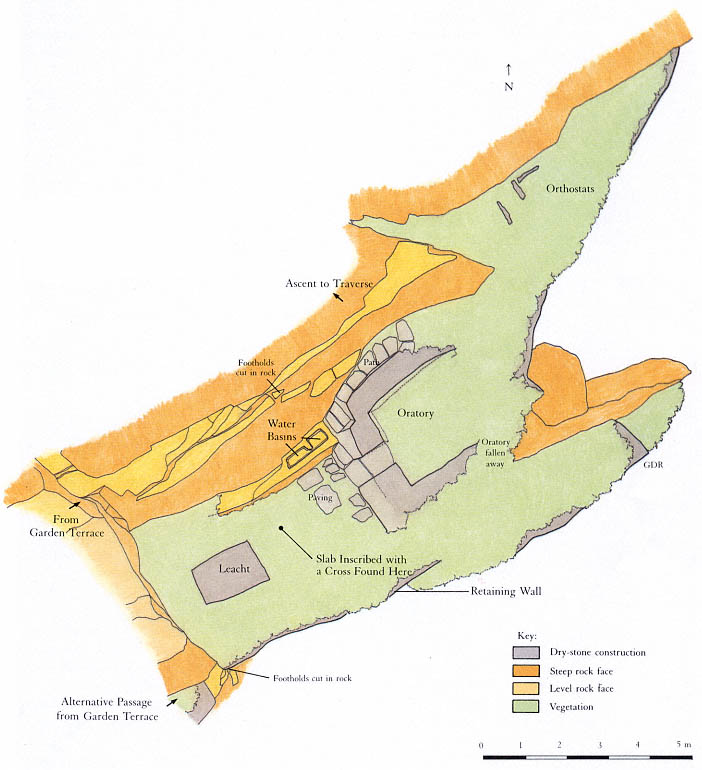

form is hard to establish. O'Leary and Snodgrass, belayed by ropes, surveyed the site with plumb lines in the summer of 1982. In 1986, Rourke resurveyed the South Peak with a plane table, and on the basis of that survey he drew the plan shown in Figure 32. The surviving remains, according to his findings, are

1. The north wall and much of the entrance wall of an oratory.

2. Two interconnecting water basins located at the base of a flagged path at the northwestern corner of the oratory.

3. Flagstones under fallen masonry at the entrance to and in front of the oratory, believed to be the remains of a completely paved terrace.

4. A rectangular leacht , a low dry-stone structure shaped like an altar, at the place where Eugene Gillan's plan (see Fig. 11) shows three objects labeled slabs. Hidden from sight by a dense overgrowth of sea campion, this structure is probably what the Ordnance Survey plan of 1841 identified as a burial ground.

5. Midway between the oratory and the leacht , lying flat on its back, a cross inscribed on a slab that, like the leacht , was hidden from sight by sea campion. This is most likely the standing cross mentioned by Lord Dunraven in 1875.

6. A small extension of the terrace east of the oratory that contains two stone slabs placed on edge at right angles to each other (Eugene Gillan mentioned them but did not show them on his plan) and a third upright slab, or orthostat, hidden by sea campion, slightly behind the other two.

7. Fragments of masonry that once formed part of a retaining wall around the perimeter of the oratory terrace.

Many of these features, with the exception of the slab incised with a cross and the paving slabs, are visible in aerial photographs like that of Figure 29. They are described in the following pages.

The Oratory

The remains of this structure consist of much of the north wall and adjoining west wall. The north wall is the more intact because it was built on bedrock as close to the rock face as possible. Its maximum height is 1.35 meters above the level of the threshold. Corbeling is evident. The internal length of the remaining north wall is 2.55 meters; the internal width of the oratory wall is 2.1 meters, with a narrow entry (.57 meter) midway in the wall. Precise overall dimensions are difficult to determine owing to collapse, but when the proportions of the small oratory in the monastery are related to this structure, they yield an estimated length of 2.75 meters. On the western, entry, side there is a plinth approximately .36 meter above the level of the threshold.[10]

[10] Plinths on the east and south sides at a slightly higher level than the one on the western side are conjectured for two reasons: tradition and the knowledge that this arrangement increases the strength of a structure that has no plinth on the north side but a path 1.18 meters above the pavement level.

Fig. 32

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Plan of the oratory terrace by Grellan Rourke, based on the plane-table survey of 1986 made

by John O'Brien and Grellan Rourke, assisted by Aidan Forde of the Kerry Mountain Rescue Team.

These fragments of wall indicate a rectangular structure aligned east to west and built of dry-stone masonry. Of the buildings in a monastery of the Early Christian period, only an oratory fits this description. All oratories—and oratories alone—were rectangular structures with longitudinal axes running east to west. The monks of this period, by contrast, dwelt in circular houses, a custom inherited from their secular ancestors. A typical example of this architectural distinction is seen in the layout of the monastery that the monks of Skellig Michael built on the other side of Christ's Saddle. It comprises six circular beehive cells and two rectangular oratories, the larger one measuring 2.44 by 3.67 meters inside, the smaller one 1.83 by 2.44 meters.[11]

The dry-stone architecture of the hermit's oratory is typical of Early Christian oratories commonly found on the islands off the west coast of Ireland, where timber was unavailable. In part, their design translated into stone the curved walls and roofs of the cruck-built timber churches that abounded during this period on the mainland of Ireland, where timber was easily obtainable.[12]

The masonry technique of the hermit's oratory, as exemplified in the remains of the north and west walls, is identical with that of the two oratories in the monastery. The smaller of the two is illustrated in Figure 33. All oratories built in this style have very thick corbeled walls with stones laid horizontally; none use mortar, dressed stones, or a rigid system of coursing. The walls in these structures were built of well-chosen medium-sized stones filled in with small stones to produce a well-compacted, even surface.

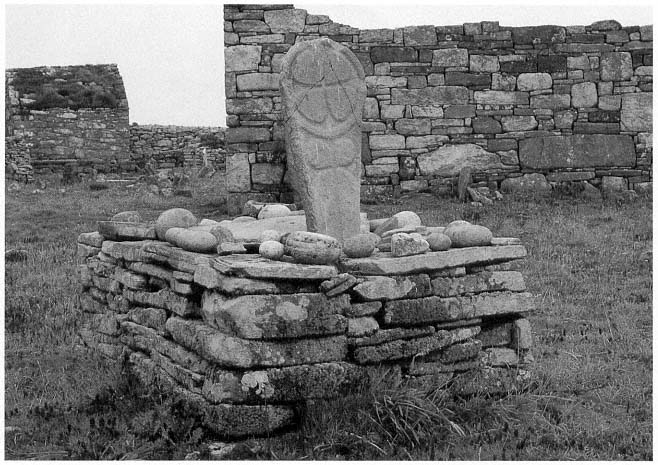

The Leacht

At the western end of the terrace approximately one meter east of the rock face are the remains of a rectangular stone-built structure 1.1 by 1.6 meters; its present height above the level of the pavement is .45 meter (Fig. 34). The basic structure is well preserved, but the uppermost level has been damaged by weathering. This setting of stones is the remains of a leacht .

Leachta , square or rectangular structures built of rough, unmortared stones, are associated with Irish Early Christian monastic sites. Today they are found primarily at the island monasteries off the west coast of Ireland. Their original distribution is unknown, as they are easily destroyed, but because some have been found in northern Britain, we know they were not limited to the western coastline. Outstanding examples are found today in the monasteries of Skellig Michael, Illauntannig, and Inishmurray. A typical example of a leacht from Inishmurray is shown in Figure 35. It is a quadrangular mass of masonry roughly one meter high, with a tall engraved cross slab set in its center (Wakeman 1893, 71, Fig. 34).

The function of leachta has long been debated. They may have been used to mark burial places, particularly for special saints, or to house relics, mostly the bones of saints; or they may have served as places for prayer, either as stations of the cross or as altars for celebrating mass. It is quite possible that all of these conjectures are correct and that leachta served different functions in different times and places.[13] Only the systematic excavation of a carefully selected group of Irish leachta might ascertain their precise function

[11] Other well-preserved examples illustrating this distinction between the designs of oratories and dwellings exist at the monasteries of Inishmurray and Illauntannig, both built, like Skellig Michael, on treeless islands. For further discussion of the distinction between circular dwellings and rectangular oratories see Horn, 1973, 23–31.

[12] On the adoption of architectural features peculiar to timber construction in Irish stone churches see Leask, 1955, vol. 1, chaps. 5 and 6. His theory has been generally accepted (Thomas, Early Christian Archaeology , 1971, 75; and de Paor and de Paor [1958], 1967, 58–60).

[13] Thomas, in Early Christian Archaeology , 1971, 169–75, gives the best summary of our current state of knowledge.

Fig. 33

Monastery of Skellig Michael. View from the south of the small oratory that served as the model for Grellan Rourke's

reconstruction in Figure 39.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 34

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Remains of a leacht .

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 35

Island monastery of Inishmurray, County Sligo. A leacht , referred to locally as altóir beag , "the little altar," one of

approximately fifteen leachta on Inishmurray of similar construction. Three lay within the monastery's walls; twelve

along the periphery of the island served as pilgrimage stations.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 36

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Oratory

terrace. The cross slab discovered in

1982 at the location indicated in

the plan of the terrace (Fig. 32).

Photograph by Lee Snodgrass.

Some leachta , however, are known to contain human bones. The larger of the two leachta in the Skellig Michael monastery is situated north of the large oratory; the other, smaller, one is built against the monastery retaining wall south of the large oratory. In the course of badly needed repair to the perimeter of these leachta , the National Monuments Service found some human bones. Because the bones were discovered by chance during the rebuilding of the wall face, not in the course of an excavation, no attempt was made to explore the leachta in depth, and the bones were returned to their original position.

The remains of a leacht on the South Peak oratory terrace give evidence of a structure too small to be the original burial place of anyone. Possibly this leacht was either a memorial shrine, containing the translated bones of a hermit, or an altar.

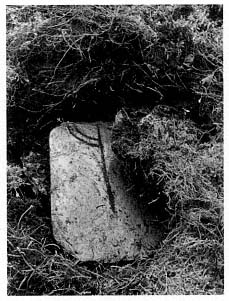

The Stone Slab Fragment Inscribed with a Cross

While taking measurements on the oratory platform, Snodgrass noticed the unusual shape of the top of a rabbit burrow. Carefully pulling aside a few tufts of sea campion, she discovered a smooth thin slab of slate with a ring cross engraved on it (Fig. 36). This is almost certainly the cross slab Lord Dunraven described in 1875 as "standing near" the oratory (see p. 18). It is a fortunate discovery because the design of the cross furnishes a clue to the date of the hermitage. Unfortunately, the slab is broken, and much of the upper part of the ring-cross design is missing. The missing fragment was not in any place accessible to surface inspection and would be difficult to find without excavation unless rabbits in the future decide to burrow in strategic places. The cross slab was placed in the care of the National Monuments Service.[14]

Such a cross slab located in the open space in front or to the side of an oratory is a classic feature of early Irish hermitages and monasteries, as Michael Herity has shown in a recent study (1984, 105–16). The chronological implications of the design on the slab are discussed in the Appendix.

The Water-Collecting Basins

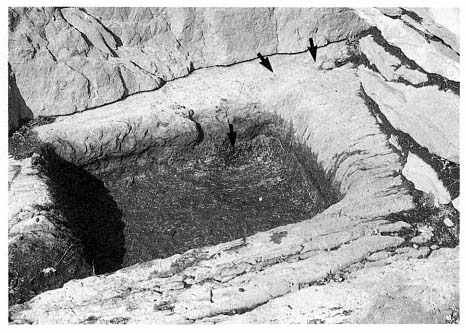

To gain access to the oratory terrace, one follows a natural ledge with steps cut into it that zigzags down the face of the cliff to a flagged path below. The existence of this path was unknown until Rourke removed sea campion from around the north wall of the oratory. At the western end of the path, steps lead down to the oratory; at the foot of these steps a critical feature turned up: two interconnecting basins chiseled out of the rock (Fig. 37). Their shape and location clearly indicate that they were used for collecting water.

This dramatic discovery gave us tangible proof of our hypothesis that a hermit lived on the South Peak. Anchorites tended to reduce their dietary needs to the lowest margin, but water was an indispensable daily requirement. The purpose for planning and constructing sophisticated water basins could only have been to enable someone to inhabit this barren crag.

On the cliff face north of the oratory two man-made grooves direct water into the basins. Water was also collected and fed into them by a channel cut under the flagstone path, visible near its termination at the base of the steps. When the water reached a certain height in the first basin, it overflowed

[14] O'Sullivan (1987) believes that this slate slab may have been brought to the island.

Fig. 37

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Oratory terrace. Detail of one of the water basins.

A channel under the steps of the flag-stone path ended at the groove (upper arrows) in

the rim of the basin at the upper right; a circular depression in the basin itself (lower

arrow) allows silt to settle. The end of the channel under the steps can be seen clearly

in Figure 31.

Photograph by Grellan Rourke.

into the second, slightly bigger, basin. This arrangement permitted the cleaning of one basin while water was retained in the second and also helped filter the water. Another component of this clever filtering system is the circular depression that collected silt at the feed end of the first basin. Careful consideration had been given to long-term use of these basins. They were near the oratory simply because there, coincidentally, the large fractured surface of the rock wall provided the best source of water.

This whole area was meticulously planned. That the masonry of the north oratory wall was built over the channel that directed water into the basins shows that the basins were carved prior to the construction of the oratory. Moreover, the northwestern corner of the oratory near the bottom of the steps is notched so that someone descending the steps has a space to turn and can avoid stepping into the water basins.

Water is always in short supply on Skellig Michael, which possesses no natural springs or wells, and must be collected from the rain that trickles down sloping rock surfaces into man-made cisterns. The vast inclined surface of rock rising behind the monastery was the source of water for the monastic community. The monks constructed two large cisterns to collect and store water running off this surface. The shortage of water on Skellig Michael and the logistics of carrying it from the monastery across Christ's Saddle and up the South Peak are practical reasons for a hermit to have established his own water supply. An equally important spiritual reason would be the desire to maintain solitude and independence from the monastery—the same desire that prompted hermits to establish gardens.

The Retaining Wall

In its original form the oratory terrace consisted of two parts: the principal area, accommodating the features just discussed, and an extension toward the east. The present length of the oratory terrace, including its eastern extension, is eighteen meters. Its greatest width is 6.7 meters. Access to the eastern extension today is dangerous; sea campion hides whatever is left of the wall that once supported a level and secure passage. There are hints of a stone wall along the outer edge of the terrace, but this area has collapsed so severely and the drop is so sheer that one can gain a sense of the extension's original condition only from a helicopter.

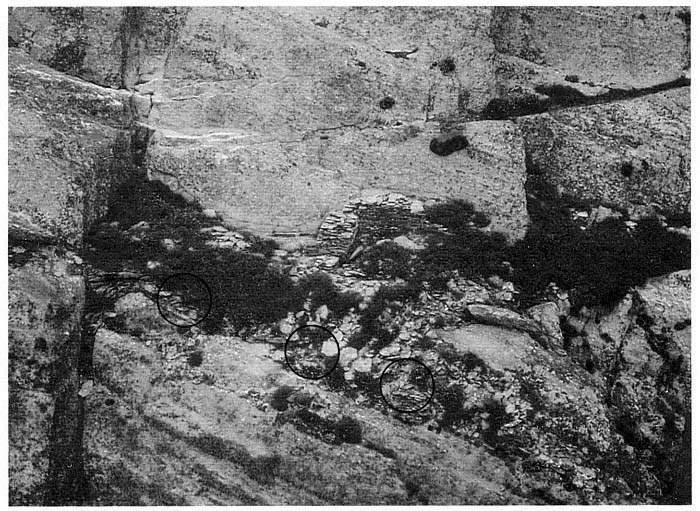

Arrows in Figure 38 show the surviving fragments of the retaining walls at the outer edge of the oratory terrace. A three-dimensional reconstruction and plan based on the plane-table survey and aerial photographs are shown in Figures 39 and 40. If the conjectural reconstruction of the retaining wall is accurate, there was barely space for the oratory. So tight was the fit that the retaining wall must have formed the eastern wall of the oratory itself.

Fig. 38

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Aerial view of the oratory terrace. Circles indicate the masonry fragments of a high retaining wall

that once formed the outer boundary of the terrace. This wall may have risen to the level of the oratory floor in successive

stages, as in Figures 39 and 40, or it may have risen in a straight line all the way up, as shown in the frontispiece.

Photograph by Con Brogan. Courtesy Office of Public Works.

Fig. 39

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Conjectural reconstruction of the oratory terrace by Grellan Rourke, based on the plane-table

survey of 1986.

Fig. 40

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Conjectural plan of the oratory terrace by Grellan

Rourke, based on the plane-table survey of 1986.

Retaining walls had to be built on this terrace before any other construction could take place. The remaining fragments of masonry suggest that two walls were necessary on the southern side, related in a complex manner to the layers of sloping bedrock beneath them. The lower, outer wall brought up the level of the terrace to provide a firm foundation for the south wall of the oratory. At the southeastern corner, where the retaining wall turns in toward the eastern extension, it must have been at least 2.5 meters high. Walls built on precariously inclined surfaces were common in the construction on Skellig Michael. Striking parallels are found, for example, in the retaining wall supporting the terrace of the small oratory of the monastery of Skellig Michael (see Fig. 33). Like the South Peak oratory, this sanctuary was built at the upper end of a surface that falls steeply away. To create a level terrace here required the construction of a retaining wall that reached a maximum height of seven meters. This wall has survived, but until repairs were made on it in 1986, its state was so perilous that it threatened momentarily to collapse.

The Eastern Extension of the Oratory Terrace

The eastern extension of the terrace measures roughly 7 by 3 meters (see Figs. 29 and 32). A narrow triangular-shaped space, it slopes steeply to both the south and the east and was originally joined to the principal terrace by a wall.[15] The extension is clearly part of the original plan for the terrace, an integral part of its construction. The labor required to create even a small amount of usable space suggests that this extension served some fundamental, important purpose.

Three stone slabs on the extension furnish a clue to this purpose. Two of them stand at right angles to each other; the third lies somewhat west of the other two (Fig. 41).[16] These upright slabs, or orthostats, were very likely part of a rectangular reliquary shrine constructed of stone slabs. The relics of holy men were venerated in Ireland, as in the rest of the Christian world during this period, although the manner in which the relics were contained and displayed varied according to local custom. In Kerry outdoor reliquary shrines may still be seen on several ecclesiastical sites, such as the island of Illaunloughan, in the Portmagee channel (Fig. 42).[17] Here, as in other known examples, the shrine is constructed of stone slabs set to form an A-shaped structure. Rectangular reliquary shrines formed by upright slabs are unknown. But at the monastery of Skellig Michael orthostats were used to form rectangular frames for the graveyard and for a leacht .

Fig. 41

Skellig Michael, South Peak.

Oratory terrace. The vertical slabs, or

orthostats, on the eastern extension of

the terrace, possibly the remains of

a reliquary shrine.

Photograph by Jenny White Marshall.

Fig. 42

Island of Illaunloughan in Portmagee channel,

County Kerry. An A-shaped reliquary

shrine formed by slabs.

Drawing by Grellan Rourke.

The creation of a separate place for a reliquary shrine makes sense if we consider the small area of the oratory terrace, but spatial separation may also reflect a symbolic significance. The area surrounding several of the Kerry slab shrines was marked off by small rectangular enclosures, a tangible reminder that the shrines were sacred.

Could a reliquary shrine have been constructed here to venerate a holy monk who had used the South Peak as a place of temporary retreat before the hermitage was built? It is easy to imagine that the arduous struggles of such an extraordinary monk might have inspired the construction of the South Peak hermitage.

[15] The total area of the terrace extension is 10.5 square meters.

[16] The first stone is .45 meter long, .35 meter high, and .15 meter thick; the stone at right angles to it measures .65 meter long, .35 meter high, and .05 meter thick. The third orthostat, located to the west of the other two, is .6 meter long, .25 meter high, and .1 meter thick.

[17] County Kerry has five extant above-ground examples of such shrines: at Caherbarnagh, Illaunloughan, Killabuonia, Killoluaig, and Kilpecan. See Henry, 1957; Thomas, 1971, 142, 143. Fanning, 1981, and O'Kelly, 1958, found, after excavating at Church Island and Reask, the remnants of two others. Thomas comments that four of the extant examples of reliquary shrines in Kerry are set within rectangular enclosures formed by vertically set stone slabs.

From the Oratory Terrace to the Summit

From the oratory terrace the climber doubles back to the trail that leads to the summit, an unusually wide and long dry-stone masonry traverse, 9 by 2 meters (Fig. 43), that ends at the foot of the last perpendicular rock face. On the way up to this traverse one views with amazement a fragment of dry-stone wall built by someone who must have been kneeling on clouds when he placed these stones on a narrow ledge that plummets into what appears to be eternity (Fig. 44). Early in our investigations we believed that this wall once formed part of a beehive cell, the dwelling of the hermit (see the discussion on pages 59–65).

The long traverse is falling away at the point where one must rely on it in beginning the final ascent. Once more the climber faces the now-familiar routine of reaching for handholds and footholds up a vertical defile before gaining the safety of a narrow ledge of solid rock just below the summit.

Fig. 43

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Aerial view of the summit and the traverse immediately below it. The final rock face to be scaled

on the way to the summit rises from this traverse. The dotted line shows the route to the traverse and the outer terrace.

Photograph taken in 1987 by Con Brogan. Courtesy Office of Public Works.

Fig. 44

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Retaining wall forming the corner of the outer terrace, viewed from the ascent

from the oratory terrace to the traverse shown in Figure 43.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

The Summit

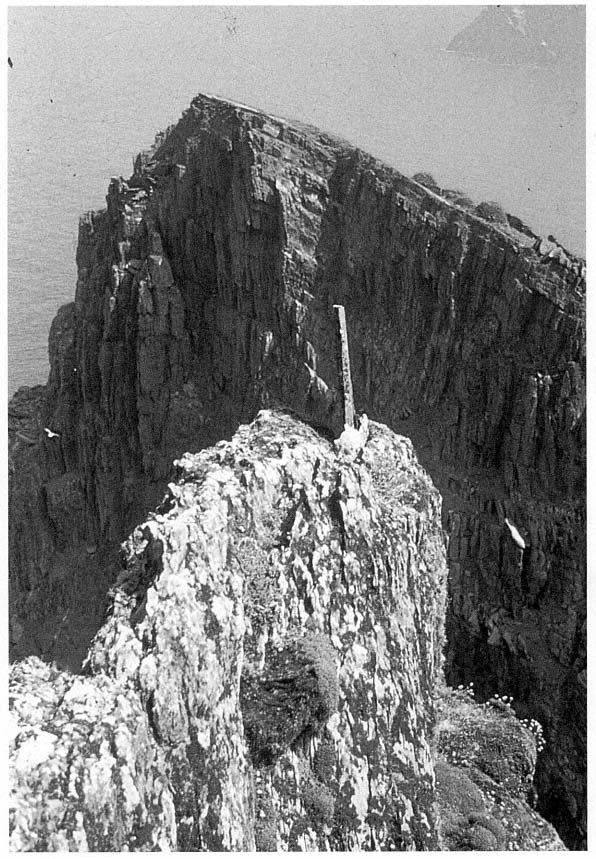

The summit is small—a few rock ledges—and consists of the ultimate peak of the rock, crowned by a modern iron weathervane, and the Spit. Smith (1756, 115) noted that pilgrims called the summit "the eagle's nest, probably from its extreme height; for here, a person seems to have got into the superior region of the air." The Spit, a narrow ridge some two meters below the weathervane on the eastern side of the peak, was legendary (Fig. 45). At its far end lay the goal of the pilgrims—the upright slab that had to be kissed. Most writers on the South Peak, from Smith in 1756 to Hayward in 1946, mentioned the slab. Sometime after 1977, however, it disappeared, probably falling from its base. No part has ever been found, and only traces of dry-stone masonry remain in the socket where the slab had been anchored by layered stone. Fortunately, archaeologists made photographs and took measurements of the

Fig. 45

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Aerial view from the south, showing the placement of the Spit.

Photograph by Walter Horn. (See Fig. 13 for a comprehensive view showing the same placement.)

slab in 1977 (Figs. 46, 47).[18] The visible part of the slab was approximately 1 meter high and 7.6 centimeters thick. No design was engraved on it, but a tiny cross, barely perceptible, was scratched into the surface, perhaps by a pilgrim.

The Spit itself is roughly 3 meters long and varies in width, narrowing in the middle to only .2 meter. It is reached from a lower rock to its west, and it can be partly circumnavigated at its base on a campion-covered ledge. The Spit projects over the jagged valley hundreds of feet below. Stepping upon it is chilling; more commonly people sit and inch along its narrow downward-sloping surface.

There are no archaeological vestiges on the summit that we can relate with certainty to the hermitage. Although the slab at the end of the Spit may have been placed there by a hermit, it may also have been erected later by zealous pilgrims. The summit was surely important to the hermitage nonetheless, for to gain access to the outer terrace it was necessary first to climb almost to the summit.

Fig. 46

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Photograph taken by Des Lavelle in 1976, showing the upright slab still standing then at

the easternmost end of the Spit.

The Outer Terrace

The isolation of the outer terrace relative to the other terraces of the hermitage, as well as its distance from them, shows clearly in Figure 43 (see also Figs. 12 and 13). Even the contour of this terrace is odd, making it the most awkward of the man-made terraces to photograph and to describe. There is no one spot or angle on the rock from which it can be viewed in its entirety; only an aerial view shows its contours (Figs. 48, 49).

[18] We are grateful to Des Lavelle and Paddy O'Leary for permitting us to use their photographs. After the disappearance of the slab in 1977, Des Lavelle searched for it not only in Christ's Saddle below but on the ocean floor, in sea diving expeditions.

Fig. 47

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Photograph taken by Paddy O'Leary in 1977, showing the upright slab that

once stood at the easternmost end of the Spit.

Fig. 48

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Aerial view of the outer terrace taken from the northern side of the peak. A short stretch of the lighthouse road is visible

at upper left as well as some of the monastic stairways connecting this road with Christ's Saddle. Arrows (from left) mark the Spit; the rock mass below

which, on the other side of the peak, the oratory terrace is located (see Fig. 45); the garden terrace; (below) the outer terrace; and the Needle's Eye.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

Fig. 49

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Another aerial view of the outer terrace. The wall that frames it faces south at the top and

north at the bottom.

Photograph by Con Brogan. Courtesy Office of Public Works.

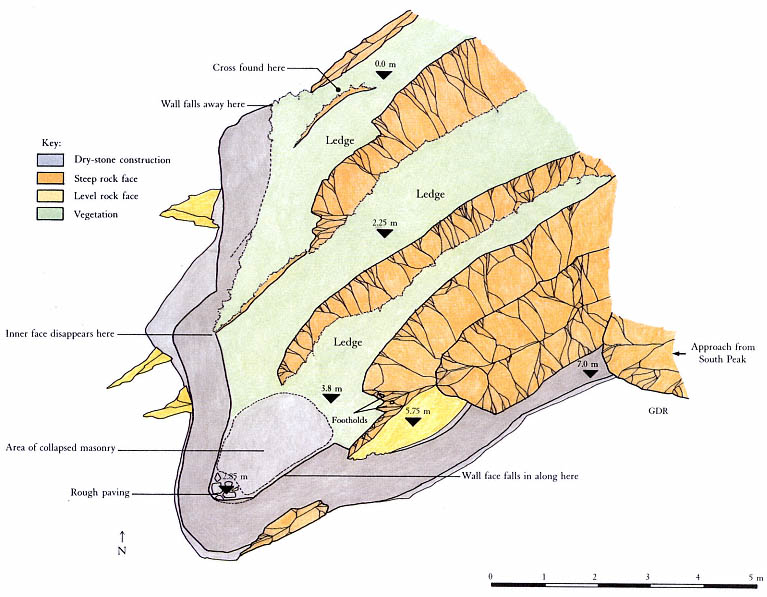

Essentially this area that we refer to as a terrace is structurally dissimilar to the others on the South Peak, for the masonry remains here consist of only a seventeen-meter-long wall along the perimeter. Nor are there signs that a single unified platform supported by retaining walls was ever intended. The construction of such a level terrace would be nearly impossible, for the topography consists of three natural stepped ledges whose elevations differ by as much as four meters. The terrain is irregular and steep, containing only a few square meters of level ground; moreover, there is no defining boundary on the northern and eastern sides.

The terrace is not mentioned in the accounts of earlier explorers, except for a casual remark of Lord Dunraven's: "There are also curious portions of an ancient wall on certain projections of rock near the Spit" (see p. 18). Liam de Paor also noted "some faint and somewhat doubtful traces of construction at one or two points along the way" (see p. 18). We believe that these remarks refer either to the small rounded section of wall visible on the climb

to the traverse below the summit (see Fig. 44) or to a larger section of wall visible from the summit itself (Fig. 50; the wall begins at about the level of the traverse and is lost to sight at the rounded section). These two small sections are all that can be seen of the outer terrace without climbing down to it.

The constant powerful winds blowing across the exposed terrain of the area below the summit make access to the outer terrace treacherous. No path exists, so one must climb gingerly down rough, sharp-edged ridges to reach the point where the masonry wall begins. Here one walks down along the top of the wall, perhaps planned at this point as a walkway, to reach a rock outcropping on which a few footholds have been carved. The footholds lead to level ground just where the wall turns a corner, where originally we believed a dry-stone beehive cell was located.

The first reaction is to gasp at the daring construction, to marvel at the stunning Atlantic beauty of the site, and to wonder, Why? Why was this ever built, this wall hanging on the edge of space? The first hermit who left

Fig. 50

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Part of the difficult path to the corner of the outer terrace. The corner lies at the outer

edge of a projecting spur of rock on the southwestern side of the South Peak some six meters below the summit.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

the monastery was going in one direction only—up, closer to God through a life of complete isolation on the island's highest point. Yet to inhabit this desolate area without shelter from winter storms was impossible. Could the outer terrace have been the location of the hermit's living quarters? Our first response to this question was an intuitive no. How could anyone survive on this storm- and rain-lashed ledge, where a freakish gust of wind might cause a loss of footing and a fatal fall? Because we could find no traces of a shelter on the lower man-made terraces on the peak, however, the question persisted. If the outer terrace were not the site of the hermit's dwelling, what was the purpose of its bizarre and extensive masonry? The construction of the wall, carefully built of medium-sized building stones with good internal and external faces, required intensive labor in an inhospitable, barely accessible area. What imperturbable man (or men) would carry building materials over a considerable distance to set stone upon stone on ledges that leave no room for even a stumble? As one contemplates this construction, one wonders whether at some point devotional submissiveness might have shifted imperceptibly into devotional hubris.

Although we know that construction is itself unequivocal evidence that the terrace was important, even as we continued our explorations we were unable to resolve our questions about the use of this site. On the most prominent part of the outer terrace, the corner, a curved and apparently corbeled wall looks like the surviving portion of a cell (Fig. 51). Further investigation showed, however, that instead of curving inward to form a small cell, the walls spread outward to follow topographical contours. Moreover, when the stones that had fallen into the interior were removed, what had looked like corbeling was revealed to be only a few courses high; the courses had been constructed so that the projecting rock became part of the wall, which elsewhere has a vertical face. Therefore it is not possible that a corbeled cell was constructed here, even though this may well have been the location of some sort of shelter.

Fig. 51

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Outer terrace. A detail of the corner, clearly revealing

what looks like corbeled stonework.

Photograph by Walter Horn.

This corner offers the best place on the outer terrace to construct an effective protection from the wind and weather, particularly because the ground level is one meter below that of the surrounding terrain. The argument for the presence of a shelter was strengthened by the discovery of a few pieces of rough flagging at the base of the corner. Had the entire area been flagged, there would have been a space just large enough for a recumbent hermit. Although final judgment awaits the clearing away of all the fallen rock, it can nevertheless be stated that an exceptionally minimal sheltered area probably existed here.

At the corner, the external height of the wall is now 2.5 meters, the internal height 1.07 meters, and the width of the wall from .6 to .8 meter at its present level. It is extraordinary that as one looks at the masonry from above, one is unaware that this semicircle of stones forms the top of a wall. Originally this wall was higher, possibly three to four meters high if it connected with the masonry above as indicated by the dotted line on Figure 52.

Fig. 52

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Remains of the walls that form the southeastern boundary of the outer terrace.

Photograph by Walter Horn. Dotted line indicates the possible height of the original masonry.

The lowest, northwestern, section of this terrace is even more puzzling than the corner. Here the wall curves, following an irrational downward course to a level 3.8 meters below the corner. Some seven meters lie between the highest point of the wall fragments on the south side of the outer terrace and those on the lowest, northwestern, side (Fig. 53). The external face of this wall is quite high in two places, about 3.2 meters. The original height of this wall and the function of the area it enclosed remain a mystery. The downward-curving wall is too far below the corner to have protected it from the wind. For this purpose, an inward-curving wall at a higher level, even at the level of the second ledge, would have been more effective. Perhaps the lower walls provided some shelter for a prayer station, however, for a small hand-sized cross, roughly shaped, was found in this area (Figs. 54 and 55).

Fig. 53

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Plan of the outer terrace by Grellan Rourke, based on the plane-table survey of 1986.

Fig. 54

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Conjectural plan of the outer terrace by Grellan Rourke, showing where the hermit

might have had a shelter under a corbeled roof.

Fig. 55

Skellig Michael, South Peak. Cross found on the northwestern

side of the outer terrace, on its lowest level.

Drawing by Grellan Rourke.

Even as we speculated about the possibility that a minimal dwelling had been constructed on the outer terrace, we faced an additional question: Could anyone have endured there during severe storms? Even on sunny, warm days the South Peak winds are strong, sometimes dangerous, and this terrace is the one most exposed to wind.

Ocean winds normally sweep horizontally over the surface of the water. When their passage is blocked by the flank of an island such as Skellig Michael, with peaks rising to a considerable height, their force changes from horizontal to vertical. The resulting wind, sweeping upward, does not cease immediately on reaching the highest points of the island but pushes beyond, curving gradually back into its horizontal course under the pressure of the wind that surrounds and follows it. The resulting condition is referred to as a leeward vortex, a comparatively calm zone suspended in turbulent winds. These wind forces are largely responsible for the warmer, calmer microclimate that exists at the location of the monastery.[19]

The effects of the monastery's microclimate were dramatically demonstrated to us when we visited Skellig Michael early in the spring of 1972. The crossing was rough, and all of us were thoroughly chilled, despite our heavy layers of sweaters and our knitted caps. As we landed, the skipper, Dermot Walsh, advised us to leave all heavy clothing below because an entirely different, warmer, climate existed up at the monastery. Although in our chilled state we were reluctant to shed our warm gear, we found the skipper's advice borne out when we reached the summit and were able to discard our heavy clothing.

Could similar illogical climatic variations be expected on the windlashed top of the South Peak? The two peaks differ significantly in their conformation and size. The monastery was built at the southern end of an extensive inclined rock plateau that rises some fifteen meters behind it, ensuring the continued upward sweep of the north and west winds past the monastery. The South Peak has a much smaller mass and rises to a greater height than the monastic peak. As it rises, it loses much of its bulk, so that at the level of the outer terrace there is no protection from the wind. A microclimate here similar to that of the monastery summit is impossible. Walls to deflect the wind would be critical for protection on this terrace.[20]

The rock formation and wall provide good protection from southern and southeastern winds. The wall on the northwestern side provides partial protection from winds. No such barrier, however, exists on the northern or northeastern sides of the terrace. There a hermit would have been exposed to the full force of the worst storms coming from those directions.

These barriers interacting could provide only marginal protection on this desolate site in good weather and would be completely inadequate in winter or during a major storm. No one could survive such conditions without better shelter. Moreover, during rainstorms, torrents of water cascading off the ledges guarantee that anyone on the outer terrace will be thoroughly

[19] The climate on the peak where the monastery is located is also determined by a combination of other factors such as solar aspect and the albedo and heat retention capacity of the native bedrock (written communication from R. Berger, professor of geography and chairman, Department of Archaeology, University of California at Los Angeles).

[20] It is possible that the better climate existing in the Early Christian period, at its peak in the tenth and twelfth centuries, may have ameliorated conditions somewhat. It is almost impossible, however, to assess the main climatic difference—that there were fewer storms of lessened intensity—for a hermit living on the South Peak.

drenched. Winds of near-hurricane force make movement to and from the terraces extremely hazardous, if not impossible. A hermit may have spent many a stormy night praying in the oratory, on the best-protected terrace on the South Peak. Even under the best conditions, however, he would frequently have been cold, wet, and at risk of serious injury or death. But the goal of an ascetic was not comfort; the Cambray Homily reminds us:

This is our denial of ourselves, if we do not indulge our desires and if we abjure our sins. This is our taking-up of our cross upon us, if we receive loss and martyrdom and suffering for Christ's sake.[21]

[21] "Ocuis numsechethse isée ar n-diltuth dúnn fanissin mani cometsam de ar tolaib ocuis ma fristossam de ar pecthib. issí ticsál ar cruche dúnn furnn ma arfóimam dammint ocus martri ocus coicsath ar Chriist" (Cambray Homily in Thesaurus Paleohibernicus , ed. and trans. Stokes and Strachan [1901], 1975, 2:245).