Jellyfish Babies

If Richard Misrach has seen "the heart of the apocalypse" at Bravo 20, Carole Gallagher has spent a decade at "American Ground Zero" (the title of her new book) in Nevada and southwestern Utah photographing and collecting the stories of its victims.[34] She is one of the founders of the Atomic Photographers Guild, arguably the most important social-documentary collaboration since the 1930s, when Roy Stryker's Farm Security Administration Photography Unit brought together the awesome lenses of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee, and Arthur Rothstein. Just as the FSA photographers dramatized the plight of the rural poor during the Depression, so the Guild has endeavored to document the human and ecological costs of the nuclear arms race. Its accomplishments include Peter Goin's revelatory Nuclear Landscapes (photographed at test-sites in the American West and the Marshall Islands) and Robert Del Tredici's biting exposé of nuclear manufacture, At Work in the Fields of the Bomb.[35]

But it is Gallagher's work that proclaims the most explicit continuity with the FSA tradition, particularly with Dorothea Lange's classical black-and-white portraiture. Indeed, she prefaces her book with a meditation on a Lange motto and incorporates some haunting Lange photographs of St. George, Utah, in 1953. There is no doubt that American Ground Zero is intended to stand on the same shelf with such New Deal—era classics as An American Exodus, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and You Have Seen Their Faces.[36] Hers, however, is a more painful book.

In the early 1980s, Gallagher moved from New York City to St. George to work full-time on her oral history of the casualties of the American nuclear test program. Beginning with its first nuclear detonation in 1951, this small

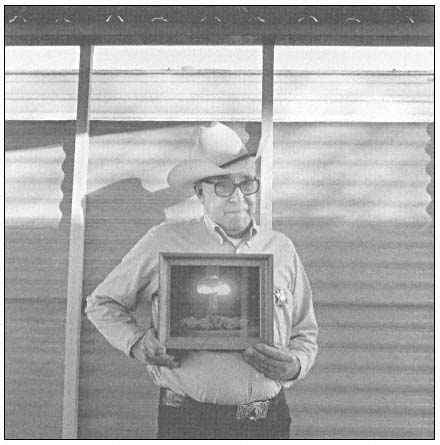

Figure 19.4

Carole Gallagher, Ken Case, the "Atomic Cowboy, " North Las Vegas.

Copyright Carole Gallagher.

Mormon city, due east of the Nevada Test Site, has been shrouded in radiation debris from scores of atmospheric and accidentally "ventilated" underground blasts. Each lethal cloud was the equivalent of billions of x-rays and contained more radiation than was released at Chernobyl in 1988. Moreover, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in the 1950s had deliberately planned for fallout to blow over the St. George region in order to avoid Las Vegas and Los Angeles. In the icy, Himmlerian jargon of a secret AEC memo unearthed by Gallagher, the targeted communities were "a low-use segment of the population."[37]

As a direct result, this downwind population (exposed to the fallout equivalent of perhaps fifty Hiroshimas) is being eaten away by cumulative cancers, neurological disorders, and genetic defects. Gallagher, for instance, talks

Map 19.2

Downwind.

about her quiet dread of going into the local K-Mart and "seeing four- and five-year-old children wearing wigs, deathly pale and obviously in chemotherapy."[38] But such horror has become routinized in a region where cancer is so densely clustered that virtually any resident can matter-of-factly rattle off long lists of tumorous or deceased friends and family. The eighty-some voices—former Nevada Test Site workers and "atomic GIs" as well as Downwinders—that comprise American Ground Zero are weary with the minutiae of pain and death.

In most of these individual stories there is one single moment of recognition that distills the terror and awe of the catastrophe that has enveloped their life. For example, two military veterans of shot Hood (a 74-kiloton hydrogen bomb detonated in July 1957) recall the vision of hell they encountered in the Nevada desert:

We'd only gone a short way when one of my men said, "Jesus Christ, look at that!" I looked where he was pointing, and what I saw horrified me. There were people in a stockade—a chain-link fence with barbed wire on top of it. Their hair was falling out and their skin seemed to be peeling off. They were wearing blue denim trousers but no shirts. . . .

I was happy, full of life before I saw that bomb, but then I understood evil and was never the same. . . . I seen how the world can end.[39]

For sheep ranchers it was the unsettling spectacle they watched season after season in their lambing sheds as irradiated ewes attempted to give birth: "Have you ever seen a five-legged lamb?"[40] For one husband, on the other hand, it was simply watching his wife wash her hair.

Four weeks after that [the atomic test] I was sittin' in the front room reading the paper and she'd gone into the bathroom to wash her hair. All at once she let out the most ungodly scream, and I run in there and there's about half her hair layin' in the washbasin! You can imagine a woman with beautiful, ravenblack hair, so black it would glint green in the sunlight just like a raven's wing, and it was long hair down onto her shoulders. There was half of it in the basin and she was as bald as old Yul Brynner.[41]

Perhaps most bone-chilling, even more than the anguished accounts of small children dying from leukemia, are the stories about the "jellyfish babies": irradiated fetuses that developed into grotesque hydatidiform moles.

I remember being worried because they said the cows would eat the hay and all this fallout had covered it and through the milk they would get radioactive iodine. . . . From four to about six months I kept a-wondering because I hadn't felt any kicks. . . . I hadn't progressed to the size of a normal pregnancy and the doctor gave me a sonogram. He couldn't see any form of a baby. . . . He did a D and C. My husband was there and he showed him what he had taken out of my uterus. There were little grapelike cysts. My husband said it looked like a bunch of peeled grapes.[42]

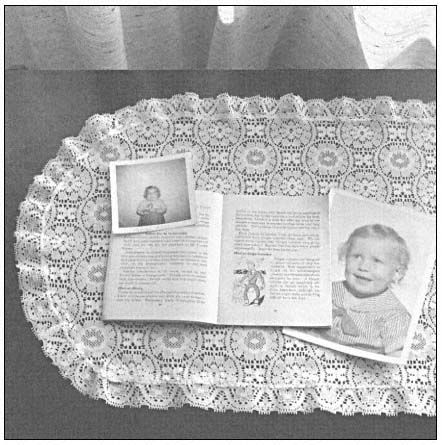

Figure 19.5

Carole Gallagher, Baby photographs of Sherry Millett, before

and during the leukemia from which she died, with the

1957 Atomic Energy Commission propaganda booklet.

Copyright Carole Gallagher.

The ordinary Americans who lived, and still live, these nightmares are rendered in great dignity in Gallagher's photographs. But she cannot suppress her frustration with the passivity of so many of the Mormon Downwinders. Their unquestioning submission to a Cold War government in Washington and an authoritarian church hierarchy in Salt Lake City disabled effective protest through the long decades of contamination. To the cynical atomocrats in the AEC, they were just gullible hicks in the sticks, suckers for soapy reassurances and idiot "the atom is your friend" propaganda films. As one subject recalled his Utah childhood: "I remember in school they showed a film once called A is for Atom, B is for the Bomb. I think most of us

who grew up in that period . . . [have now] added C is for Cancer. D is for Death. "[43]

Indeed, most of the people interviewed by Gallagher seem to have had a harder time coming to grips with government deception than with cancer. Ironically, Washington waged its secret nuclear war against the most patriotic cross-section of the population imaginable, a virtual Norman Rockwell tapestry of Americana: gung-ho Marines, ultra-loyal Test Site workers, Nevada cowboys and tungsten miners, Mormon farmers, and freckle-faced Utah schoolchildren. For forty years the Atomic Energy Commission and its successor, the Department of Energy, have lied about exposure levels, covered up Chernobyl-sized accidents, suppressed research on the contamination of the milk supply, ruined the reputation of dissident scientists, abducted hundreds of body parts from victims, and conducted a ruthless legal war to deny compensation to the Downwinders.[44] A 1980 congressional study accused the agencies of "fraud upon the court," but Gallagher uses a stronger word—"genocide"-and reminds us that "lack of vigilance and control of the weaponeers" has morally and economically "played a large role in bankrupting . . . not just one superpower but two."[45]

And what has been the ultimate cost? For decades the AEC cover-up prevented the accumulation of statistics or the initiation of research that might provide some minimal parameters. However, an unpublished report by a Carter administration task force (quoted by Philip Fradkin) determined that 170,000 people had been exposed to contamination within a 250-mile radius of the Nevada Test Site. In addition, roughly 250,000 servicemen, some of them cowering in trenches a few thousand yards from ground zero, took part in atomic war games in Nevada and the Marshall Islands during the 1950s and early 1960s. Together with the Test Site workforce, then, it is reasonable to estimate that at least 500,000 people were exposed to intense, short-range effects of nuclear detonation. (For comparison, this is the maximum figure quoted by students of the fallout effects from tests at the Semipalatinsk Polygon.)[46]

But these figures are barely suggestive of the real scale of nuclear toxicity. Another million Americans have worked in nuclear weapons plants since 1945, and some of these plants, especially the giant Hanford complex in Washington, have contaminated their environments with secret, deadly emissions, including radioactive iodine.[47] Most of the urban Midwest and Northeast, moreover, was downwind of the 1950s atmospheric tests, and storm fronts frequently dumped carcinogenic, radioisotope "hot spots" as far east as New York City. As the commander of the elite Air Force squadron responsible for monitoring the nuclear test clouds during the 1950S told Gallagher (he was suffering from cancer): "There isn't anybody in the United States who isn't a downwinder. . . . When we followed the clouds, we went all

over the United States from east to west. . . . Where are you going to draw the line?"[48]