Misrach's Inferno

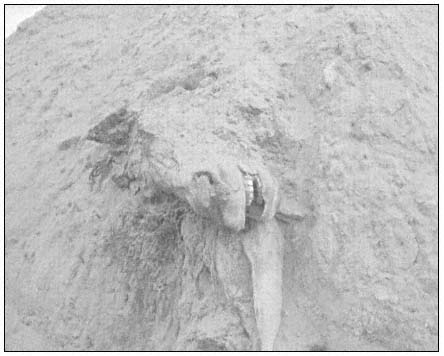

A horse head extrudes from a haphazardly bulldozed mass grave. A dead colt—its forelegs raised gracefully as in a gallop—lies in the embrace of its mother. Albino tumbleweed are strewn randomly atop a tangled pyramid of rotting cattle, sheep, horses, and wild mustangs. Bloated by decay, the whole cadaverous mass seems to be struggling to rise. A Minoan bull pokes its eyeless head from the sand. A weird, almost Jurassic skeleton—except for a hoof, it might be the remains of a pterosaur—is sprawled next to a rusty pool of unspeakable vileness. The desert reeks of putrefication.

Photographer Richard Misrach shot this sequence of 8 x 10 color photographs in 1985–87 at various dead-animal disposal sites located near reputed plutonium "hot spots" and military toxic dumps in Nevada (see fig. 19.1). As a short text explains, it is commonplace for local livestock to die mysteriously, or give birth to monstrous offspring. Ranchers are officially encouraged to dump the cadavers, no questions asked, in unmarked, county-run pits. Misrach originally heard of this "Boschlike" landscape from a Paiute poet. When he asked for directions, he was advised to drive into the desert and watch for flocks of crows. The carrion birds feast on the eyes of dead livestock.[11]

"The Pit" has been compared to Picasso's Guernica. It is certainly a nightmare reconfiguration of traditional cowboy clichés. The lush photographs are repellent, elegiac, and hypnotic at the same time. Indeed Misrach may have produced the single most disturbing image of the American West since ethnologist James Mooney countered Frederic Remington's popular paintings of heroic cavalry charges with stark photographs of the frozen corpses of Indian women and children slaughtered by the Seventh Cavalry's Hotchkiss guns at Wounded Knee in 1890.[12]

But this holocaust of beasts is only one installment ("canto VI") in a huge mural of forbidden visions called Desert Cantos. Misrach is a connoisseur of trespass who, since the late 1970s, has penetrated some of the most secretive spaces of the Pentagon Desert in California, Nevada, and Utah. Each of his fourteen completed cantos (the work is still in progress) builds drama around a "found metaphor" that dissolves the boundary between documentary and allegory. Invariably there is an unsettling tension between the violence of the images and the elegance of their composition.

The earliest cantos (his "desert noir" period?) were formal aesthetic experiments influenced by readings in various cabalistic sources. They are

Figure 19.1

Richard Misrach, Dead Animals #327, 1987.

Copyright Richard Misrach.

mysterious phantasmagorias detached from any explicit sociopolitical context: the desert on fire, a drowned gazebo in the Salton Sea, a palm being swallowed by a sinister sand dune, and so on.[13] By the mid-1980s, however, Misrach put aside Blake and Castaneda, and began to produce politically engaged exposés of the Cold War's impact upon the American West. Focusing on Nevada, where the military controls 4 million acres of land and 70 percent of the airspace, he was fascinated by the strange stories told by angry ranchers: "night raids . . . by Navy helicopters, laser-burned cows, the bombing of historic towns, and unbearable supersonic flights." With the help of two improbable anti-Pentagon activists, a small-town physician named Doc Bargen and a gritty bush pilot named Dick Holmes, Misrach spent eighteen months photographing a huge tract of public land in central Nevada that had been bombed, illegally and continuously, for almost forty years. To the Navy this landscape of almost incomprehensible devastation, sown with live ammo and unexploded warheads, is simply "Bravo 20." To Misrach, on the other hand, it is "the epicenter . . . the heart of the apocalypse":

Figure 19.2

Richard Misrach, Bombs, Destroyed Vehicles, and Lone Rock , 1987.

Copyright Richard Misrach.

It was the most graphically ravaged environment I had ever seen. . . . I wandered for hours amongst the craters. There were thousands of them. Some were small, shallow pits the size of a bathtub, others were gargantuan excavations as large as a suburban two-car garage. Some were bone dry, with walls of "traumatized earth" splatterings, others were eerie pools of blood-red or emerald-green water. Some had crystallized into strange salt formations. Some were decorated with the remains of blown-up jeeps, tanks, and trucks.[14]

Although Misrach's photographs of the pulverized public domain, published in 1990, riveted national attention on the bombing of the West, it was a bittersweet achievement. His pilot friend Dick Holmes, whom he had photographed raising the American flag over a lunarized hill in a delicious parody on the Apollo astronauts, was killed in an inexplicable plane crash. The Bush administration, meanwhile, accelerated the modernization of bombing ranges in Nevada, Utah, and Idaho. Huge swathes of the remote West, including Bravo 20, have been updated into electronically scored, multi-target

Map 19.1

Pentagon Nevada.

grids which, from space, must look like a colossal Pentagon videogameboard.

In his most recent collection of cantos, Violent Legacies (which includes "The Pit"), Misrach offers a haunting, visual archeology of "Project W-47," the supersecret final assembly and flight testing of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The hangar that housed the Enola Gay still stands (indeed, a sign warns: "Use of deadly force authorized") amidst the ruins of Wendover Air Base in the Great Salt Desert of Utah. In the context of incipient genocide, the fossil flight-crew humor of 1945 is unnerving. Thus a fading slogan over the A-bomb assembly building reads BLOOD, SWEAT AND BEERS, While graffiti on the administrative headquarters commands EAT MY

FALLOUT. The rest of the base complex, including the atomic bomb storage bunkers and loading pits, has eroded into megalithic abstractions that evoke the ground-zero helter-skelter of J. G. Ballard's famous short story "The Terminal Beach." Outlined against ochre desert mountains (the Newfoundland Range, I believe), the forgotten architecture and casual detritus of the first nuclear war are almost beautiful.[15]

In cultivating a neo-pictorialist style, Misrach plays subtle tricks on the sublime. He can look Kurtz's Horror straight in the face and make a picture postcard of it. This attention to the aesthetics of murder infuriates some partisans of traditional black-and-white political documentarism, but it also explains Misrach's extraordinary popularity. He reveals the terrible, hypnotizing beauty of Nature in its death throes, of Landscape as Inferno. We have no choice but to look.

If there is little precedent for this in previous photography of the American West, it has a rich resonance in contemporary—especially Latin American—political fiction. Discussing the role of folk apocalypticism in the novels of García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes, Lois Zamora inadvertently supplies an apt characterization of Desert Cantos :

The literary devices of biblical apocalypse and magical realism coincide in their hyperbolic narration and in their surreal images of utter chaos and unutterable-perfection. And in both cases, [this] surrealism is not principally conceived for psychological effect, as in earlier European examples of the mode, but is instead grounded in social and political realities and is designed to communicate the writers' objections to those realities.[16]