About-Faces

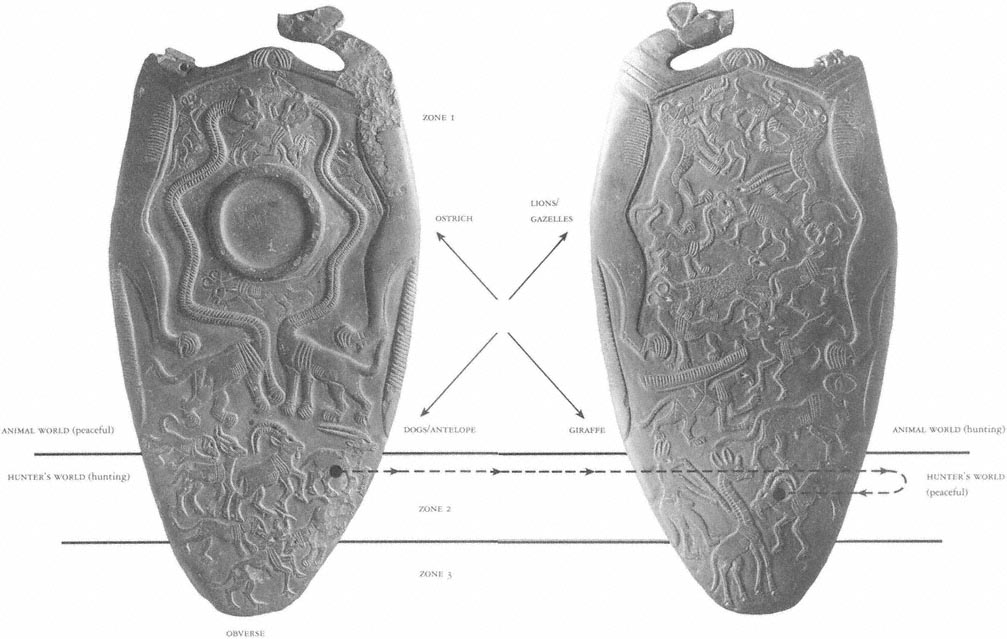

The Oxford Palette (Fig. 26) replicates—repeats and revises—these metaphorics in a much more complicated image. Roughly the same height as (42 cm.) and slightly wider than (22 cm.) the Ostrich Palette, it can be shown on typological grounds to be probably somewhat later in date, certainly Nagada IIIa

Fig. 26.

Oxford Palette: carved schist cosmetic palette, late predynastic (Nagada IIc/d or IIIa),

from Main Deposit at Hierakonpolis.

Courtesy Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

(see Davis 1989: 139–40 for full discussion). The masked hunters on these two palettes are the only such instances identifiable in late prehistoric and early canonical Egyptian art. The hunter appears on the Oxford Palette with human dress (belt and pouch or bag) and human limbs, hands, and feet but with a jackal's tail and head or mask, piping a flute at the edge of a group of beasts hunting their victims (reverse bottom left). This puzzling figure has been identified as a "monkey with long ears" (Legge 1900: 132) and as a "fox" (Vandier 1952: 582). He is certainly a human hunter, but it cannot be maintained, as some have said, that he is grasping a stick (Williams and Logan 1987); he holds the implement or instrument he carries up to his mouth. The uncertainty of commentators about the identity and properties of this figure testifies to the general difficulty of determining how the overall image works.

The Oxford Palette echoes the content of the animal-rows and carnivores-and-prey formulas ranged along straight baselines in the images found on the knife handles and comb. And in all likelihood it develops from these images while strongly reconfiguring the formulas. The palette exemplifies the compositional mode in late prehistoric Egyptian art that commentators have sometimes called "chaotic" or "disorderly" or at least "less formal" than canonical art (see, for instance, Groenewegen-Frankfort 1951: 18; Fischer 1958: 65, note 4). Putting the matter in positive terms, the disposition of the figures in the "space" of the scene is indicated by the relative orientation of their individual baselines observed in "plan" or bird's-eye views (Fig. 27); the viewer must look "down" on the scene in handling the image. For example, on the obverse (or saucer) side of the palette, in the first row of animals below the serpent-necked panthers or "serpopards,"[2] the three horned victims of the attacking dog are meant to be running in the same direction and roughly in a straight line. The right-most creature is shown to be veering slightly to one side, namely, to the left of the general line of flight. The pursuing dog is shown to be attacking the hindmost victim by running at it from behind and one side—that is, again, from the left of the line of movement of the victims.

Once properly understood, this compositional technique (see also Davis 1976) is both informative and flexible. Nevertheless the viewer must shuttle through, twist around, and rise above the scene to grasp it as a scene rather

Fig. 27.

Structure of the Oxford Palette, obverse and reverse.

than as a merely decorative (space-filling or rhythmic) disposition of elements on a field with figures spread at right angles to the line of sight. Indeed, like the masked hunter within the depiction, the viewer enters the scene and becomes part of it in the movement of viewing.

The most hieratic passage of the image—explicitly echoing the animal-row and animal-pair formulas—appears in the top two-thirds of the obverse side of the palette, around the cosmetic saucer. As the evidence of the chain of replications strongly suggests, late prehistoric compositions on decorated palettes are meant to be viewed beginning with this obverse (saucer) side and with the saucer area playing a key role. Thus in this area of the image on the Oxford Palette the viewer is introduced to it through a symmetrically balanced, almost heraldic expression whose narrative complexity and ellipsis unfolds only later in the time of viewing as the object is handled and the image spread on both sides is scanned from top to bottom and side to side. In order to make the point, my discussion will necessarily follow the interpretation of the image in the time of the viewing—the network of internal associations being forged and further questions being raised as the viewer moves through the image and tries to understand its coherence. Here it is crucial to remember that the threads of the image cannot be completely tied up together all at once; rather, they are raveled, and to some extent unraveled, in a complex unfolding as the object is handled and scanned. For example, the viewer encounters ellipses or gaps only to the extent that expectations being set up in the viewing are being frustrated; the viewer feels the image to be a revision of elements of the existing chain of replications only to the extent that the chain seems to be both repeated and modified as the viewer progresses through its latest version. Such facts imply that a verbal description of the viewing experience is difficult to produce and to follow. But I will come back to a summary of the "whole" structure of the image, as finally deciphered.

At the top of the palette and extending along the edges, the saucer is surrounded by two wild dogs (Cape hunting dog) clasping one another's paws. Their heads (one missing) project beyond the main surface. In this respect the Oxford Palette resembles the more routine funerary palettes (Petrie 1920, 1921) with projecting double bird heads or other animal outlines, but it is unusual in

having the two animals facing each other with the entire length of their bodies stretched along the sides. The wild dogs have usually been interpreted as emblematic creatures similar to those in Minoan-Mycenaean painting, where "the intention is not so much a naturalistic presentation as the transfer of power or protection to the object they adorn or confront" (Immerwahr 1990: 136). Thus we might see the wild dogs on the Oxford Palette as "frames" in a sense: they are "outside" the image but provide for its integrity.

The dogs' heraldic, framing function might, however, bear an analogical or metaphorical relation to the narrative presentation proper. Wild dogs also appear within the image on both sides of the palette: on the obverse, there are three running along the lines established by the snakelike necks of the serpopards (the Hunter's Palette [Fig. 28] brings this formal conceit into the narrative itself) and on the reverse one wild dog moves, with its head turned back, toward the left edge. We observed on the Carnarvon handle (Fig. 23), an "earlier" work in the chain of replications, that the wild hunting dog may have been an analog for the person of the human owner, perhaps the "hunter" himself. It is possible that the framing dogs on the Oxford Palette do so as well, inasmuch as the palette is grasped by its human owner precisely with thumbs placed over the wild dogs' bodies at the edge of the object, their heads projecting in front as an extension of the owner's hands.

There is an important revision in this representation, even if it has indeed been maintained from the earlier to the later replication. The wild dogs that surmount the image as a whole do not frame everything the pictorial text relates. Outside the area bounded by the bodies of the wild dogs along the edges of the palette, the bottom third of the image depicts not wild dogs—the Cape hunting dog has the status of a natural carnivore like a jackal or lion—but domesticated hunting mastiffs, differentiated by floppy ears and heavy studded collars, who more directly figure the human hunter's presence in the scene. The surmounting wild dogs provide one overall frame or title, "announcing" the theme of the representation of the human hunter within the scene of nature. Once some metaphorical and narrative expectations are set up, getting the viewer started, the further development of the image supplements this announcement in several ways.

At the top of the framed area, below the clasped paws of the wild dogs and between the heads of the two serpopards, is depicted a single ostrich—a creature that is clearly near the beginning of the pictorial text in the formal structure of the image. If we regard the surmounting dogs as a framing announcement providing a preliminary specification of the image, the ostrich initiates its development proper in and through the act of viewing.

Within the chain of replications of late prehistoric representation, the derivation of the ostrich almost certainly lies in earlier works such as the Ostrich Palette (Fig. 25). Its replication in later contexts substantially revises and even refuses the metaphorical or narrative message of the earlier, much simpler one. As we saw in the first part of this chapter, the ostrich on the Ostrich Palette was about to be attacked and captured by a masked human hunter with upraised arms about to throw himself on his prey. Here, at the top of the Oxford Palette, the ostrich lifts its wings as if to take flight, escaping the human or any other hunter. Although the masked human hunter does appear on the Oxford Palette, it is not as a predator following and pursuing his victim, as on the Ostrich Palette's revision of the animal-rows and carnivores-and-prey formulas. Instead, on the Oxford Palette the masked human hunter is shown on the other side of the image (bottom reverse) as if luring and setting up an attack to be carried out by the hunter's dogs. Thus the depiction of the masked hunter on the Ostrich Palette has been wedged apart.

The ostrich opening the image on the Oxford Palette establishes not only the repetition of the theme of the hunt but also the very fact of its revision precisely as the wedging apart and supplementation of earlier formulas. At this level the ostrich probably alludes to the disturbance of the rows of birds in the animal-rows formula. What had intervened in those rows—the giraffe appearing in the grouping of snake and stork and giraffe—appears now in a crucial position on the Oxford Palette at the farthest available distance from the ostrich at the top of the obverse: namely, at the bottom of the reverse. In other words, the two elements of the formulaic grouping (snake and stork = serpopards and ostrich) are separated from the third (giraffe) in the creation of an extensive image spread on both sides of the palette. Thus the image reinstates the animal-rows and carnivores-and-prey configurations, supplementing them, however,

with a complex metaphorical and narrative depiction of the presence of the human hunter.

Presuming that this complex image is not viewable all at once, like the earlier animal-rows or carnivores-and-prey formulas or the hunting scene on the Ostrich Palette, how does the viewer know how to proceed through it? Although the question is difficult to answer definitively, it is likely that the figure of the ostrich beginning the pictorial text provides the necessary instructions for viewing. A ground-running bird depicted as about to take its short and awkward flight, the ostrich plausibly represents a key to its cipher, the mechanism of viewing the viewer must adopt to interpret the image: the viewer follows a straight line and then takes a "jump" or "leap" in a flip from the obverse to the reverse of the palette.

In this way the viewer activates chronological and causal transitions from one state of affairs to another in the underlying narrative. (A pictorial narrative must somehow generate such mobility in what would otherwise be depictions that do not represent ongoing processes; see the Appendix.) Thus he or she produces the narrative in a structured interaction with a text that provides the appropriate conditions for its own intelligibility—for example, by framing, "sign posting," and other devices organizing passages so that the viewer goes through them in the relevant order. In late prehistoric Egyptian art a cipher key of the kind I identify here seems to appear in all the complex images it is possible to reconstruct more or less completely as narratives. The artist produces the act of viewing the narrative—produces the viewer's production of narrative—by a textual specification that is, as such, non-narrative, although the same element, in this case the ostrich, may also have a thematic status in the image as a whole. While the framing wild dogs announce the general theme of the image, to be supplemented and modified as the viewer proceeds, the ostrich provides the appropriate "guide for the reader."

Within the area of the image surmounted by the wild dogs and below the ostrich, two serpopards are shown licking the back of a stumbling gazelle. The motif is often interpreted as depicting a nonviolent if incipiently aggressive action; its specific designation and connotations are not known. A related passage appears in the same position on the reverse side of the palette: two

rampant" lions are depicted as biting two gazelles belonging to the same species (with short up-curved horns and short tail) as the gazelle on the obverse. As replications of the carnivores-and-prey formula, these particular obverse and reverse motifs are unusual; more standard versions of the formula appear in lower portions of the image on both sides. Rather than chasing their prey, the carnivores in the top passages approach frontally; and the action in both cases is ambiguous—on the obverse "licking" rather than attacking, and on the reverse "biting" in a fashion that almost resembles kissing. The face-to-face encounters involving serpopards and lions with gazelles—seemingly free of conflict—must be metaphorical rather than literal. The wild dogs facing one another and clasping paws, surmounting the whole and framing the top two-thirds of the image on both sides of the palette, thus provide a symbolic announcement of this theme.

To make sense of this portion of the image, the viewer will consider it in the context of the whole: he or she proceeds from the obverse, where the single gazelle is licked by two serpopards, to the reverse—encountered after a flip of the palette—where two gazelles are confronted by two lions. Because they have the same formal arrangement—both motifs appear directly below and are framed by the wild dogs clasping paws—the viewer regards each in terms of the other. Consequently a question arises in viewing the image about the passage of depiction at the top of the obverse. Because there are two gazelles on the reverse, should there not be another gazelle on the obverse, the "twin" of the gazelle at the top? The viewer discovers this "absent" gazelle at the bottom of the obverse, outside the area framed by the wild dogs' bodies and below the serpopards. Here, in a standard carnivores-and-prey formula, the gazelle is pursued by one of the hunter's dogs, which attacks from behind and pounces on the back of its victim. Having encountered the motifs of "licking" and "biting" or "kissing," the viewer now construes the standard formula as an explicit alternative to or revision of the passages of depiction at the top of the image on both sides of the palette.

The discovery of the "second" or "twin" gazelle and the interpretation of the overall image it helps to sustain is likely to be made in the middle of the time of viewing the scene as a whole. The viewer understands the gazelle at

the top of the obverse and the gazelle in the complex group at the bottom of the obverse as necessarily related only after he or she has turned to the other side of the palette, at the top of which the two gazelles are brought close together in their relation to the lions. This search for and understanding of the "twin" gazelle is structured by the other creatures appearing at the top of the obverse side of the image along with the "first" gazelle and the serpopards—namely, the ostrich between the heads of the serpopards and the three wild dogs running along their sinuous necks. Just as there are three animals in the scene of nature hunting (the gazelle and two serpopards), so must there be three wild dogs accompanying the scene—for the wild dogs, as the surmounting dogs attest, represent the overall theme of the hunt. Two of these internal wild dogs are in symmetrical placement, facing each other on the left and right edges. The third, just below the cosmetic saucer, is linked symmetrically not with a twin of itself but rather with the gazelle and ostrich above the cosmetic saucer. The gazelle runs and the ostrich "jumps" and "flies" from left to right (that is, from obverse over to reverse) while the third wild dog runs right to left (that is, back again). Jointly, then, they indicate, first, the flipping of the palette—in this move, the viewer discovers the two gazelles and two lions in exactly the same position on the reverse as the single gazelle and serpopards on the obverse and thus raises the question about the "twin" gazelle on the obverse—and, second, the return to the obverse, in which the viewer discovers the metaphorical place of the entire top of the image on both sides in relation to the bottom outside the wild dogs. The ostrich is the node of the activating mechanism, under the wild dogs, between the heads of the serpopards, and directly above the stumbling gazelle; the two (left and right) wild dogs run "up" toward it; and it is opposite, although reversed in orientation to, the third wild dog below the saucer.

If the viewer discovers two gazelles on the reverse and therefore asks about two gazelles on the obverse, so, then, does a similar question arise about the wild dogs. There are three on the obverse. Should there not be a fourth, completing the parallel with two gazelles and two attackers, on the reverse? The construction of the parallel takes place in and through the time of viewing as the viewer moves back and forth between the two sides of the palette. The

fourth wild dog appears more or less where the viewer comes to expect to find it—namely, in the complex scene of nature hunting presented on the top of the reverse opposite the three dogs on the obverse. Here, next to the hind foot of the framing wild canine on the left edge of the palette, the dog, running right to left (or reverse to obverse) seems to halt and turn back on itself. It has sighted an antelope running toward it, but this creature, although running right to left, also turns its head and thus does not see its danger.

As the viewer is led from the top side of the obverse—with ostrich, gazelle, serpopards, and wild dogs—to consider the top of the reverse, he or she encounters there, just below the two lion-and-gazelle pairs, another face-to-face pair of attacker and supposed victim: a serpopard bites the leg of an oryx. Despite the precedent of the topmost passage of depiction on the other side, containing the two serpopards, and the passage of depiction above it on its own side, containing the pairs of lions and gazelles, this serpopard does not have a twin. Instead it is paired with its prey—who does not, in the end, turn out necessarily to be a victim. (The encounter may not be fatal, since the oryx is bitten on the leg, rather than face or throat, and actually reappears on the obverse, outside the framed portion of the top of the image, where its "twin" is pursued by, but may still escape, the hunter's dogs.) This portion of the image—the entire passage on the top two-thirds of the reverse, framed by the wild dogs at the sides—takes the viewer, from top to bottom, through a complex sequence depicting the relations of hunter and hunted within the scene of nature hunting.

All in all, six pairs of hunter and victim are depicted in the framed portion of the image on the reverse side of the palette. Like those just described—two lions attacking two gazelles and the serpopard biting an oryx—the next two creatures see one another directly. But, for the first time in the sequence, they are presented almost as a standard carnivores-and-prey pair: the leopard follows the hartebeest, who turns around to look at its attacker.

This arrangement is reversed immediately below, where an antelope evades the preceding conflict—in bird's-eye view, it is running "out" of the melee—but looks back over itself at the hartebeest, which confronts own death.

It is the antelope's possible attacker, the wild dog to the left, who turns back over itself toward its possible victim. But whether the wild dog will necessarily attack and kill the antelope is not clear, for the wild dog's "twin" in the same compositional position on the obverse is running right to left, or "away from" the melee. As the viewer comes to understand it, then, it is as if the wild dog on the reverse pauses—poised between flight and attack—and then continues to run away. Should the unseeing antelope therefore escape death at this moment, in direct contrast with the hartebeest aware of (but unable to prevent) its fate immediately above, the viewer must ask about the conclusion. If the wild dog continues to run away, then what happens to the antelope? It would be an ellipsis in the pictorial text of the reverse top portion, as well as an anomaly in the entire image, for the matter of the antelope's fate to be left hanging. Like the oryx escaping the serpopard, the antelope is depicted as attacked in the obverse bottom portion of the image—but by a different enemy altogether. Here it turns its head to look in the direction from which the danger had been coming on the reverse—that is, to the "left" and therefore in the direction of the place where the wild dog had been standing. But its action cannot now avail it, for the wild dog is replaced by the hunter's dogs, which attack from both sides.

The six-part sequence of scenes of nature hunting on the reverse top portion of the image is completed, finally, by the pair, at the bottom of the framed portion of the image on the reverse, depicting a winged griffin attacking a fleeing bull ox.[3] This motif is the only absolutely standard presentation of the carnivores-and-prey formula (compare the attacking griffin on the Gebel el-Tarif knife handle [Fig. 20]), with an attacker placed behind and seeing a quarry that is unaware of danger. The viewer encounters this pair after the entire sequence, from top to bottom, has presented other possibilities: a face-to-face encounter (lions and gazelles), a face-to-face encounter with attacking beast of prey but a possible escape and postponed death for the victim (serpopard and oryx), an attack from behind with the victim's death despite seeing its danger (leopard and hartebeest), and an attack from the front unseen by the victim

whose death is nonetheless deferred (wild dog and antelope). We can put these results in tabular fashion as follows:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The summary shows it to be a fact of the world of nature hunting—as presented in the top portion of the image spread across obverse and reverse sides—that the victim may or may not be killed if approached from in front, when it must see what it confronts, and may or may not be killed if attacked from behind when it can still see its attacker, but is always killed if attacked from behind when failing to see the attacker. The presentation begins with the most ambiguous aspect of this "rule," the serpopards and gazelle on the top of the obverse, and ends with the most unambiguous, the griffin attacking a bull ox, toward the bottom of the reverse.

Juxtaposed with the entire statement in the portion of the image framed by the wild dogs, enclosing the scene of nature hunting, a revised and reversed statement appears in the portion of the image outside the frame in the bottom one-third of the palette on both sides. Here the victim, the antelope at the bottom of the obverse, is killed even when it can see its danger—precisely because, when hunted by man, it can never see the whole of that danger; the threat, like its very depiction on the palette itself, is always partly on the other side of what is seen .

Although the top portion of the image establishes a definitive statement—it relates a narrative of nature hunting—questions about or ellipses within it are progressively encountered by the viewer. For example, the viewer must wonder about the twin of the top gazelle on the obverse or about the fate of the oryx and the antelope in the middle part of the sequence on the reverse. These gaps are completed in the bottom portion of the image as spread across the obverse and reverse sides. Here the "twin" gazelle, the oryx, and the antelope reappear in a new context: the masked human hunter and his surrogates are introduced into the scene of nature hunting in a way that explicitly recounts the difference between nature hunting per se and nature hunted by man, a difference not specifically observed on the Ostrich Palette (Fig. 25). The full image, then, is an intertwined juxtaposition of top (framed) portion and bottom (unframed) portion, each completing itself on the obverse and reverse sides of the palette while relating to the other above or below it.

Unlike the top portion of the image, which works from obverse to reverse, the bottom implies a chronology that works from reverse to obverse. The hunter's dogs, on the obverse, must have been released by the hunter, on the reverse, even if the viewer's experience—technically speaking, the story of the fabula in the text of the image (see Appendix)—may go initially in the other direction. At the chronological and causal beginning of the narrative, the bottom zone of the reverse of the palette and perhaps the last zone to be viewed, a giraffe stands between the masked human hunter and a bearded ibex running toward them. According to the bird's-eye view of the composition, the ibex runs "into" the giraffe by moving "down" from the melee of the scene of nature hunting presented in the framed portion of the image above it. The neck, face, and ears of the giraffe are treated so as to be formally similar to the flute, face, and ears of the human hunter; it stands between the hunter, placed at the edge of the scene and apparently advancing into it, and the scene of nature hunting itself. The giraffe, then, is in effect the mask of the masked hunter.

Running toward the lure of the hunter's music—if this is indeed the sense of the group depicted here—the ibex sees the giraffe rather than its real enemy. The danger of the hunter for the ibex and the other animals lies outside the scene altogether, as is made clear on the other side of the palette. Here, at

exactly this level in the composition of the image (the top of the bottom, unframed zone), one of the hunter's mastiffs, the beast that will actually perform the kill, pursues the group of three animals (gazelle, ibex, and oryx) carried around the palette by the fourth (the ibex's twin) coming up to face the masked hunter standing in the very position of his dog on the other side.

From the vantage point of the ibex at the bottom of the reverse side, the danger in front of it is masked in two senses. First, the hunter is masked from the ibex's direct view by the giraffe. Second, even if the ibex were to see him as he really appears, it would only, still, encounter a mask—namely, the jackal-masked hunter piping a flute rather than preparing to kill. The ibex's real danger, the hunter's dogs, remains unseen and behind it on the "other side" of both hunter and ibex. Thus, in this compositional position on the obverse, the ibex and the oryx are depicted, from the vantage point of the reverse, as turned around and running in the other direction, away from the hunter's dogs—a decision fraught with danger, for, in this direction of viewing the image, the oryx will encounter the serpopard.

On the bottom of the obverse, the gazelle to the left and behind the ibex is being killed by the hunting dog; the oryx to the right and in front of it will be attacked by the serpopard in the immediate "future" on the reverse of the palette. The bearded ibex itself is not shown being directly attacked and killed. As the viewer inspects the two sides, the image therefore suggests the hopeless position of the ibex; avoiding a literal depiction of the ibex's destruction, it leaves the obvious implication for the viewer to construct. But this condition of nature when hunted by the human hunter is represented metaphorically at the bottom of the unframed zone on the obverse. Here a hapless gazelle, beset by two of the hunter's dogs, twin of the gazelle with which the scene begins at the top, is the only creature in the entire image spread across the two sides of the palette to be attacked from both sides. Wholly unlike the two gazelles attacked by two lions at the top of the reverse, the gazelle at the bottom of the obverse is depicted as being unable to see either of its two enemies, however it tries. Its head is turned back from the dog coming up toward its "right" front, but it is also turned to its own "right" back rather than to the "left" back where the other dog appears. To represent the confusion in its hopeless situation—

figuring the entire scene of representation, including the viewer's interpretations in producing it—the gazelle's horns are depicted in a surreal overlapping twist, perhaps the most important key to the cipher of the image.

This metaphor of the hunter's dog attacking the twisted gazelle synthesizes for the viewer the image as a referential whole. In particular, it explains the forward mask of the masked hunter in the same place on the other side—namely, the peaceful giraffe that the ibex does see depicted as disguising a destructive blow it cannot see. But the human hunter himself, entering the scene with his dogs, remains masked. He is not directly shown to wield the blow—in this case, to set his dogs upon the animals—as the master might be shown in canonical Egyptian art. Instead his decisive act must take place outside or, as it were, between the sides of the image. Like the "licking" serpopards and the "kissing" lions in the top portion of the image, his depicted relation with his prey is decidedly ambiguous: he plays a flute, which could be both entertainment and lure. The truth of his action is unfolded only progressively in the relating of the full narrative. Unlike the masked hunter depicted on the Ostrich Palette (Fig. 25), coming up directly behind his prey as if he were actually an animal, the human hunter on the Oxford Palette is behind his dogs. As in all instances of nature hunting, it is the dogs—or other carnivores—who actually kill the prey; thus the human hunter pursuing the animal hunters hunting their prey, like the jackal whose mask he wears, is represented as if he were a scavenger who only discovers the corpses of the animals. But of course the viewer understands that the human hunter is not actually a scavenger, for he owns and trains the dogs and sets them on their prey; his jackal form is the mask of his real identity as deadly hunter in front of his prey.

As we will see in Chapter 5, the image on the Oxford Palette will be replicated and revised. For example, the Hunter's Palette (Fig. 28) will show the nonmasked human hunters pitted directly against their prey. Here the image is on one side of the palette—and the hunter surrounding the victim will come into the literal depiction in another fashion. On the Battlefield Palette (Fig. 33) the scavenger will have a distinctively different role in the pictorial metaphorics and narrative, but, as on the Oxford Palette, a specific relationship between the enemy's sight and the ruler's representations will be sustained.[4]

In my description of the Oxford Palette, I attempt to follow the structure and sequence of the narrative—its symbolic content or meaning is still obscure—as it is distributed across the surface of the object, in active manipulation, and through the time of its viewing. Like the two sides of the Carnarvon handle (Fig. 23), the two sides of the Oxford Palette are related closely as passages of depiction in a single complex image (Fig. 27). In effect, the top of the obverse masks the blow at the top of the reverse, whereas the bottom of the reverse masks the blow at the bottom of the obverse; but even the blows depicted are not presented fully or literally. Figured by the jumping, flying ostrich and the gazelle's plaited horns, the palette constructs a sophisticated double twist, tied together from top to bottom and from side to side. Compared with the decorated knife handles and comb and the Ostrich Palette, the place from which the human hunter advances is shown on the Oxford Palette in some of its power and danger: it is advanced further into the depicted scene. Indeed, compared with the Brooklyn and Carnarvon knife handles or the Ostrich Palette, it is only superficially that the masked hunter seems to be at the edge of the scene. In the double twist, wrapping around, and folding over of the image as it is spread across the palette in the time of the viewing, the masked hunter becomes its crucial central node—even as his blow remains literally undepicted on the other side of his mask.