VI—

The Trilogy: Africa, the Afro-American Symphony, and Symphony in G Minor

Africa, the Afro-American Symphony and the Symphony in G Minor comprise a trilogy of works whose composition occupied their creator over a period of years, during which time other works were also written and played.

Perhaps most intellectual young American Negroes think much about their African background. William Grant Still's meditations on this sub-

ject took a musical form. It was in 1930 that he wrote Africa, a symphonic poem in three movements, designed as an American Negro's wholly fanciful concept of the cradle of his Race, formed on the folklore of generations. Because the movements have descriptive titles, one might call Africa a suite, but the composer prefers to describe it as a poem, believing that the unity of the idea justifies it.

Africa, which critics said was "not as inchoate or as desultory as his Darker America and Journal of a Wanderer, " quickly became one of his most highly praised compositions. During five years, four different versions of Africa were scored, three of which were performed. In January of 1933 appeared the fifth and supposedly last version. But in 1935 Still noted a flaw, and a sixth version came into being. This constant revision is not unusual with him. Many things he destroyed completely because, in his own judgment, they "weren't good enough." He constantly criticizes his own work and constantly revises. This results in much extra labor, but he feels that final perfection justifies it.

The three movements of Africa are titled: "Land of Peace," "Land of Romance," "Land of Superstition."[5] In the first movement, two kinds of peace are portrayed, the first pastoral, the second spiritual. It is an active peace and quietude, not a lethargic slumber. "Land of Romance" is tinged with sadness, intensified by the orchestral treatment of the first part of the movement. It ends on a note of passionate longing. In the final movement, two forms of superstition appear: that of the pagan African and that of the followers of Mohammed. The music abounds in the suggestion of startling unspoken fears, lurking terrors. It subtly conveys the idea that the race has not yet shaken off primitive beliefs, despite the influence of civilization. The opening theme later proceeds into a rather Oriental motif, by which the composer intended to depict the arid Northern part of Africa. Africa places the listener instantly on the soil of the Dark Continent; it is not merely a picture of abstract beauty.

Africa was dedicated to the eminent flautist, Georges Barrère, and was performed by the Barrère ensemble in New York in 1930, by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in Rochester in 1930, at the Festival of American Music in Bad Homburg in 1931, in Paris by the Pasdeloup Orchestra in 1933, in Rome under the leadership of Werner Janssen, and in part by Paul Whiteman's Orchestra in New York in 1933, by the New York Sinfonietta in 1933, and under the composer's direction by the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra in 1936.

The second composition in the trilogy, the Afro-American Symphony, was composed in 1930, dedicated to Irving Schwerké and performed by

the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in Rochester in 1931 and 1932 and in part under the direction of Dr. Howard Hanson (who introduced it) in Berlin, Stuttgart and Leipzig in 1933. These dates show conclusively that Still's work preceded that of another Negro composer who in 1934 was heralded as having written the first Negro symphony.

This Afro-American Symphony really became widely known through the energy of its publishers who were canny enough not to allow important publications to gather dust on their shelves. From the date the symphony was accepted for publication, and since its performance under Hans Lange and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, this symphony has had many performances. Leopold Stokowski played its last movement in many American cities on his nationwide tour with the Philadelphia Orchestra, thus bringing it to the attention of many American music-lovers.

A reviewer said, "There is not a cheap or banal passage in the entire composition." A Rochester critic opined that it was "by far the most direct in appeal to a general audience than any of his music heard here, and it has a greater technical finish. To some extent he has replaced that arresting vigor one has admired by deft sophistication." Another Rochester critic dubbed it "honest, sincere music . . . developed without recourse to theatrical invention." David Kessler said it "seemed a much more important work on second hearing than it did the first time it was played"—genuine praise, indeed. An audience in Berlin broke a twenty-year tradition to encore the Scherzo from this Symphony when Dr. Howard Hanson conducted it there; several years later, when Karl Krueger conducted it in Budapest, his audience did the same thing.

Of this symphony, Still wrote:

At the time it was written, no thought was given to a program for the Afro-American Symphony, the program being added after the completion of the work. I have regretted this step because in this particular instance a program is decidedly inadequate. The program devised at that time stated that the music portrayed the "sons of the soil," that is that it offered a composite musical portrait of those Afro-Americans who have not responded completely to the cultural influences of today. It is true that an interpretation of that sort may be read into the music. Nevertheless, one who hears it is quite sure to discover other meanings which are probably broader in their scope. He may find that the piece portrays four distinct types of Afro-Americans whose sole relationship is the physical one of dark skins. On the other hand, he may find that the music offers the sorrows and joys, the struggles and achievements of an individual Afro-American. Also it is quite probable that the music will

Example 8.

Principal theme, first movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

speak to him of moods peculiar to colored Americans. Unquestionably, various other interpretations may be read into the music.

Each movement of this Symphony presents a definite emotion, excerpts from poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar being included in the score for the purpose of explaining these emotions. Each movement has a suggestive title: the first is Longing, the second Sorrow, the third (or the Scherzo) Humor, and the fourth Sincerity. In it, I have stressed an original motif in the blues idiom, employed as the principal theme of the first movement, and appearing in various forms in the succeeding movements, where I have tried to present it in a characteristic manner.

When judged by the laws of musical form the Symphony is somewhat irregular. This irregularity is in my estimation justified since it has no ill effect on the proportional balance of the composition. Moreover, when one considers that an architect is free to design new forms of buildings, and bears in mind the freedom permitted creators in other fields of art, he can hardly deny a composer the privilege of altering established forms as long as the sense of proportion is justified.

The Moderato Assai, the first movement, departs to an extent from the Sonata Allegro form. The first division might be called the Exposition. This begins with an introduction in A flat Major, derived from the principal theme, and is followed by the principal theme (example 8). Following this, the principal theme reappears in a new treatment, and with a rhythmic counterpoint, which is extended to form a bridge between the repetition of the principal theme and a transition that strongly resembles a development of the principal theme. The subordinate theme is in G Major (the fact that the keys are here unrelated is a departure) and is in the style of a Spiritual (example 9). Then, instead of a Codetta, there is a transitional passage, starting in G Minor and leading to the Development in Division Two, in A Flat Major, the material here derived from the principal theme. Division Three is a Recapitulation,

Example 9.

Subordinate theme, first movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

Example 10.

Principal theme, second movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

Example 11.

Secondary theme, second movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

in which there is a radical departure. The subordinate theme reappears in A Flat Major, instead of a repetition of the principal theme. There is a re-transition before the final appearance of the principal theme in A Flat Major in a new and rhythmic treatment. The movement ends with a coda.

The second movement is short. There is a six measure introduction, scored entirely for strings and muffled tympani. The material of this introduction is derived from the principal (blues) theme of the first movement. The principal theme of the second movement, however, is played by oboe alone, accompanied by violas and 'celli divisi and by a flute obligato. It is eight measures in length (example 10). This theme is repeated, then extended slightly. The gap between the principal theme of the second movement and its subordinate theme is bridged by four measures of material taken from the introduction to the second movement, and used in transitional fashion. The subordinate theme is given to the flute at the outset, and is derived from the principal theme of the first movement (example 11). Thereafter, appear four-measure blocks of this same melody treated in different ways, a development of an individual sort. This lasts for thirty measures and leads to a repetition of the movement's principal theme, extended and working up to a fermata, and a pause. The movement ends with the introductory material given to muted strings and muffled tympani, here extended to eight measures.

Example 12.

Principal theme, third movement (Scherzo), Afro-American

Symphony .

Used by permission.

Example 13.

Transformation of the symphony's main theme, Coda

of third movement.

Used by permission.

Example 14.

Principal theme, fourth movement, Afro-American Symphony .

Used by permission.

The form of the third movement, or Scherzo (the humorous aspect of religious fervor) is also unusual. The Introduction, in E Flat Minor, is derived from the principal theme, yet resembles in a general way the episodic material. The principal theme is in A Flat Major (example 12). Just before the Coda there appears a transformation of the blues theme of the first movement, as an accompanying figure (example 13).

The fourth movement, Lento con Risoluzione, has a decidedly free form. The principal theme is announced at the outset by strings accompanied by clarinets, trombones and tuba (example 14). The subordinate theme in A Major is derived from the blues theme (example 15). This theme is presented again in C Major and is then developed, the development being extended and presenting, during its course, the blues theme in a different form. Much later in the score, there is a new development in 6/8 time which enters abruptly. In

Example 15.

Subordinate theme, fourth movement, Afro-American

Symphony .

Used by permission.

this, the blues theme reappears in still another form. Just before the coda brings the movement to its close, the principal theme of the movement is re-stated.

The harmonies employed in the Symphony are quite conventional except in a few places. The use of this style of harmonization was necessary in order to attain simplicity and to intensify in the music those qualities which enable the hearers to recognize it as Negro music. The orchestration was planned with a view to the attainment of effective simplicity.[6]

Third in the trilogy is the Symphony in G Minor which, at the earnest request of Dr. Leopold Stokowski, who introduced it with the Philadelphia Orchestra in Philadelphia in December of 1937 and then played it twice in New York City a few days later, was subtitled Song of a New Race . This music, too, was composed as abstract music, with no thought of a program. Its creation occupied the composer for more than a year. Measure by measure, phrase by phrase, the work grew slowly, until it became one of the finest of his symphonic works to date. The theme of the second movement alone is masterly in its inspiration (example 16).

Of this Symphony (dedicated to Isabel Morse Jones), the composer has written the following:

This Symphony in G Minor is related to my Afro-American Symphony being, in fact, a sort of extension or evolution of the latter. This relationship is implied musically through the affinity of the principal theme of the first movement of the Symphony in G Minor to the principal theme of the fourth, or last, movement of the Afro-American .

It may be said that the purpose of the Symphony in G Minor is to point musically to changes wrought in a people through the progressive and transmuting spirit of America. I prefer to think of it as an abstract piece of music, but, for the benefit of those who like interpretations of their music, I have written the following notes:

The Afro-American Symphony represented the Negro of days not far removed from the Civil War. The Symphony in G Minor represents the

Example 16.

Symphony in G Minor (No. 2), "Song of a New Race," second

movement, opening.

Used by permission.

American colored man of today, in so many instances a totally new individual produced through the fusion of White, Indian and Negro bloods.

The four movements in the Afro-American Symphony were subtitled "Longing," "Sorrow," "Humor" (expressed through religious fervor) and "Sincerity," or "Aspiration." In the Symphony in G Minor, longing has progressed beyond a passive state and has been converted into active effort; sorrow has given way to a more philosophic attitude in which the individual has ceased pitying himself, knowing that he can advance only through a desire for spiritual growth and by nobility of purpose; religious fervor and the rough humor of the folk have been replaced by a more mundane form of emotional release that is more closely allied to that of other peoples; and aspiration is now tempered with the desire to give to humanity the best that their African Heritage has given them.

Linton Martin, writing in the Philadelphia Inquirer for December 11, 1937, said "Song of a New Race by the Negro composer, William Grant Still, was of absorbing interest, unmistakably racial in thematic material and rhythms, and triumphantly articulate in expression of moods, ranging from the exuberance of jazz to brooding wistfulness." A few days later, Olin Downes wrote: "It is interesting to perceive how far Mr. Still can go in a purely melodic manner, without resort to many of the traditional symphonic devices to fill out his tonal design." Leopold Stokowski, however, wrote to the composer that the new work was a

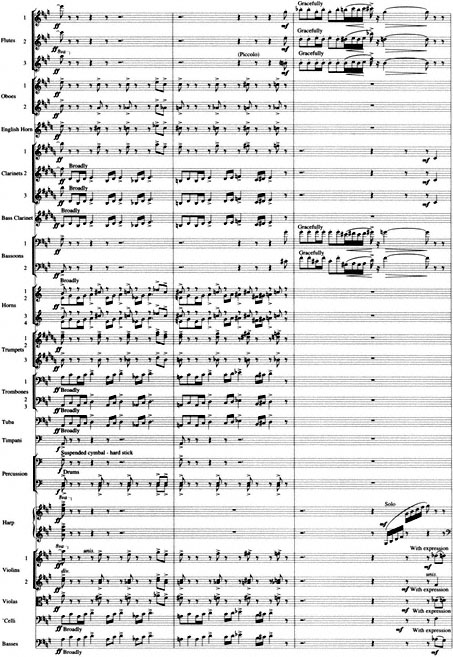

Example 17.

Symphony in G Minor , page from the composer's score.

Used by permission.

tremendous advance over the former symphony, beautiful and vital though that was.