PART II—

THEMATIC

Three—

The Body and the Mind, The Doctor and the Patient:

Negotiating Hysteria

Roy Porter

Diseases

A central aim of medical history must surely be to chart the history of disease, for without that, we will never fully gain a sense of people's health, sufferings, morbidity profiles, life expectations, and expectations out of life.[1] Some historians go so far as to claim that pathogens have perhaps been the most potent agents of sociopolitical change at large.[2] And without proper understanding of microbes and toxins, it has been contended, the history of hysteria will be misread. For according to Mary Matossian, what contemporaries and scholars alike have identified as eruptions of mass hysteria—the late medieval witch craze, religious revivals, la grande peur —ought properly to be read as the symptoms of ergotism.[3]

Yet, as is shown by scholarly scepticism toward such claims, identifying past diseases presents daunting challenges. With all our semiotic skills and modern clinical expertise, are we able to decode the medical texts, eyewitness accounts, and mortality records of bygone centuries and alien cultures, and trace the natural histories of diseases?[4] Was the "ague" of early modern England truly malaria, or "quinsey" a streptococcal infection? On the basis of Thucydides' description of the so-called "great plague" of Athens, scholars have come up with dozens of disease labels (though such is the debris of discarded identifications, that only fools should rush in).[5]

The hazards of retrospective diagnosis teach a salutary scepticism. After all, as epidemiologists know, microorganisms themselves mutate, following unpredictable evolutionary biogeographies. Perhaps the Athe-

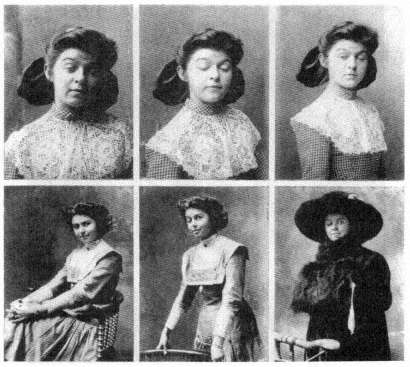

nian plague, or the decimating "great sweat" of early-Tudor England, that mysterious disorder, were due to pathogens that came and went. And, in any case, our forebears may have reacted to this or that infection in ways foreign to modern symptomatologies—to the despair of the historical epidemiologist but the delight of the shameless relativist. The former expects disease to obey laws, regularly producing predictable effects; the latter may, by contrast, luxuriate in the heterogeneity of subjective experiences of affliction.[6] Medical historians must soldier on, using what evidence they can: skeletal remains, artifacts (paintings, photographs), and written testimony, though words may be false friends: what early moderns called "cholera" was certainly not the "Asiatic" cholera that swept Europe and North America in the nineteenth century, although its identity still baffles inquiry.[7]

So what of hysteria? Are historians to think of hysteria as a true disease, whose rise and fall can, in principle, be plotted down the centuries, so long as we exercise vigilance against anachronistic translation of archaic concepts? Or is it a veritable joker in the taxonomic pack, a promiscuous diagnostic fly-by-night, never faithfully wedded to an authentic malady—or worse, a wholly spurious entity, a fancy-free disease name, like Prester John, independent of any corresponding disease-thing, a cover-up for medical ignorance? Or, worse still, may hysteria truly have been the doctors' Waterloo: a real disorder, but, as Alan Krohn hints, one so "elusive" as to have slipped our nosological nets?[8]

For reasons clear to every reader of this book, "hysteria" inevitably induces doubts. Yet why shouldn't a history of hysteria be written? Not one expecting (in the manner of Professor Matossian) to unearth a microtoxin as vera causa , nor even one tracing progress from medical confusion to medical clarification. But a history of hysteria experiences, that is, of people labeled as hysterical, or identifying themselves as suffering from the condition, and embodying it in their behavior; one taking into account all the intricate negotiations, denials, and contestations bound to mediate such multifarious sickness presentations.[9]

Such a history could be written while judgment is suspended about hysteria's ontology. Scholars, after all, habitually trace the incidence of various fevers—low, spotted, and remitting—while remaining in the dark as to their etiology; "war fever" or "gold fever" are also discussed without obligation to specify the root cause of these drives. The embossing of hysteria—perhaps unlike spotted fever—with cultural meanings does not discredit such a project, but makes it all the more inviting.

We should expect not a single, unbroken narrative but scatters of occurrences: histories of hysterias, in fact. Yet the chronological epicenter

is bound to be the nineteenth century. As Helen King has shown in chapter 1, antiquity and medieval Europe had no need of the hysteria concept.[10] And—so runs G. S. Rousseau's discussion in the previous chapter—though from Renaissance to Enlightenment physicians developed the hysteria diagnosis, it remained largely subordinate to discourses about melancholy and the nerves.

It was during the nineteenth century that hysteria moved center-stage. It became the explicit theme of scores of medical texts.[11] Its investigation and treatment made the fame and fortunes of towering medical figures—Charcot, Breuer, Janet, and Freud. Hysteria came to be seen as the open sesame to impenetrable riddles of existence: religious ecstasy, sexual deviation, and, above all, that mystery of mysteries, woman.

Moreover, people began to suffer from hysteria, or (what amounts to the same thing) to be said to suffer from hysteria, in substantial numbers. In novels[12] and newspapers, police reports and social surveys, the predicaments of mass society, crowd behavior, street life, and social pathology were endlessly anatomized in the idiom of hysteria.[13] And—often in compound forms, such as hystero-epilepsy—hysteria became traded as a common currency between the sick, their families, their medical attendants, and the culture at large: witness the repeated illness episodes undergone in the 1830s by Ada Lovelace, Byron's daughter (needless to say, the word carried deeply divergent nuances for Ada, her mother, her husband, and her flock of medical attendants).[14]

Hysteria's clientele broadened. One senses that, in the eighteenth century, the term still circulated in rather confined, indeed, refined, circles. That changed. As may be seen from Charcot's practice, hysteria became, at least by the belle epoque , established as a disorder of males as well as females,[15] of sensitive and silly alike: perhaps none was wholly immune. In his discussion in chapter 5, Sander Gilman documents the extension of "hysterical" to certain ethnic types, notably Semites.[16]

Furthermore, as Edward Shorter has emphasized, a multitude of nineteenth-century records—police, hospital, and Poor Law—testify that the terminology of hysteria shed most of its class exclusiveness. Shop girls, seamstresses, servants, street walkers, engine drivers, navvies, wives, mothers, and husbands too, were now eligible for depiction as hysterical alongside their betters, and not merely (as in Restoration comedy) as mimicry à la mode.[17] The coming of mass society evidently democratized the disorder.

Institutional evidence attests this. In the mid-nineteenth century, Robert Carter alluded to hysteria epidemics in workhouses as though such outbreaks were common.[18] Victorian asylum records show patients

sectioned with hysteria written into their diagnosis or figuring in their case notes.[19] Establishments—hydros, spas, retreats, sanatoria, nursing homes—started catering to private patients suffering from hysteriform conditions.[20] Shorter has explored the procedures that filtered invalids of a certain class or income into superior institutions (with greater freedom and privileges), under choicer diagnostic verbiage. Considerable linguistic tact was requisite. Too psychiatric a diagnosis could suggest psychosis, or downright lunacy, with connotations unacceptable for the family. An overly physicalist term might come too near the bone by suggesting a tubercular condition or syphilis and its sequelae. Dexterity with diagnostic euphemisms was at a premium: this became the age of "neurasthenia."[21]

Finally, and to us, most famously, there was the string of clients climbing the stairs at Berggasse 19. If some were "hysterics" largely by virtue of being so designated by others, Freud's patients, it seems, mainly volunteered. Freud strenuously contested his patients' "denials," but none of them, not even Dora, seems to have denied that he or she was hysterical.[22]

One could thus trace the hysteria wave (or one might say craze, epidemic, or simply spread). Its cresting at that time seems perfectly amenable to explanation, without need to resort to crass reduction-ism (vulgar labeling or social control theory, or the medical dominance model). Cultures, groups, and individuals respond in different ways to life's pains and pressures; idioms of suffering and sickness can be more or less expressive; direct or indirect; emotional, verbal, or physical; articulated through inner feelings or outward gesture. Varied repertoires clearly register the tensions, prohibitions, and opportunities afforded by the culture (or subculture) at large, reacting to expectations of approval and disapproval, legitimation and shame, to prospects of primary penalty and secondary gain.[23]

Some societies legitimize psychological presentations of suffering, while others sanction somatic expression. Affluent New Yorkers are today allowed, even expected, to act out trauma psychologically. Mao's China, by contrast, apparently condemned such performances as lapses into inadmissible subjectivism and political deviancy. Hence "feeling bad" in the Republic had to be couched in terms of a physical debility or malfunction that escaped censure and solicited sympathy and relief.[24]

In this respect, the sickness culture of nineteenth-century Europe and North America seems to have borne some resemblance to modern China. In a fiercely competitive economic world, high performance was expected, with few safety nets for failures. There were intense pressures

toward inculcating self-control, self-discipline, and outward conformity (bourgeois respectability). Personal responsibility, probity, and piety were, furthermore, internalized through strict moral training, imparted via hallowed socialization agencies like the family, neighborhood, school, and chapel. Guilt, shame, and disapproval were always nigh. In such stringent force fields, feelings of distress or resentment, anxiety or anger, were inevitable but difficult to manage; they were commonly "repressed" or rerouted into one of the rare forms of expression that were legitimate: the presentation of physical illness. Being sick afforded respite and release to those who needed temporarily or permanently to opt out.[25] And the system was skewed so that some took the strain more than others. Women were disproportionately burdened, being more isolated and incurring intenser expectations of moral and sexual rectitude; ladies often had time for reflection without outlets for their talents.[26]

Such concatenations of circumstances—high pressures, few safety valves—seem almost tailor-made for hysteria, viewed (as, of course, many nineteenth-century physicians themselves viewed it) as a disorder whereby nonspecific distress was given somatic contours.

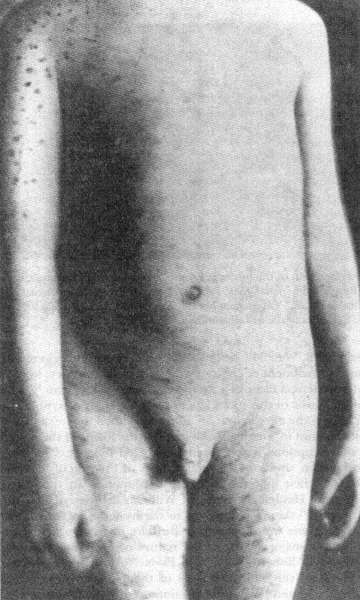

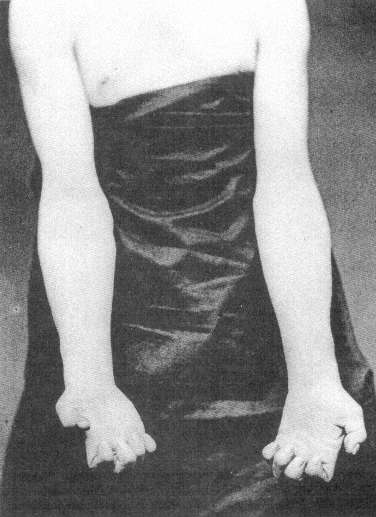

Symptom choice involves complex learning and imitative processes. Picking up hysteria was aided by the fact that nineteenth-century public life put on view an abundance of physical peculiarities: gait disorders, paralyses, limps, palsies, and other comparable handicaps. Such conditions were the effects of birth defects and inherited diseases, of syphilis, lead and mercurial poisons at the workplace, of overdosing with unsafe drugs, industrial accidents, and high levels of alcoholism with consequent delirium tremens . The visibility of real biomedical neurological disorders enticed and authenticated those seeking a sickness stylistics for expressing inner pains.

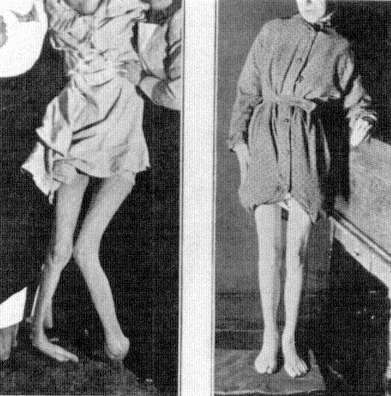

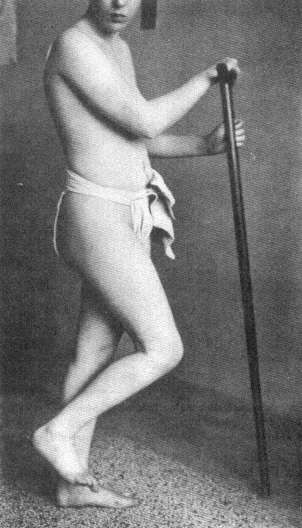

Shorter has further argued, as have many feminist scholars, that a certain rhyme and reason may be discerned in the symptom selection.[27] The gastric disorders men widely "adopted" were compatible with continuing an active life, and hence with a certain model of masculinity. Being a hysterical woman, by contrast, meant exhibiting a battery of incapacitating symptoms emblematic of helplessness, enfeeblement, and (with lower limb paralyses) immobilization, acting out thereby, through sickness pantomime, the sufferer's actual social condition. Hysteria was thus mock escape by self-mutilation (a male analogue finally emerged in the First World War with shell shock).

We need detailed a history "from below" of rank-and-file nineteenth-century hysterics, and not just of such "immortals" as Blanche Wittmann, Léonie B., and Anna O. It would enhance our grasp of the elec-

tive affinities between disease and culture, confirming the adage that every society gets the disorders it deserves. Alongside epidemiology, medical history needs to study the history of illness, that is, of sufferers' conditions, regardless of science's judgment upon their authenticity. Aside from metaphysical questions (is hysteria a real disease?), it is clear that our great grandparents suffered from hysteria, no less than Elizabethans underwent the "sweat" or we succumb to "depression," "stress," or low-back pain; it is the job of historians to explain how and why.[28]

This grass-roots history of hysterics, this social history of symptoms, should be high on the agenda. But it is not what the remainder of this chapter tackles. Instead, I shall explore the medical profession's attempts to resolve the hysteria mystery, a disorder enigmatic because it hovered elusively between the organic and the psychological, or (transvaluating that ambivalence) because it muddled the medical and the moral, or (put yet another way) because it was ever discrediting its own credentials (were sufferers sick or shamming?). In this, I have in mind several larger goals. I want to explore the opportunities hysteria offered, and the puzzles it posed, for the medical profession: was it to be their finest hour or their Waterloo? I shall probe how differential readings of hysteria suited diverse sectors of a profession increasingly specialized and divided. Not least, I wish to gauge hysteria's symbolic replay (parody even) of the interactions between doctors and patients, suggesting how, in psychoanalysis, it launched a wildly new and deeply aberrant script of doctor-patient interplay.

Hysteria/Mysteria

Nineteenth-century doctors habitually represented hysteria as a challenge, a tough nut to crack. Chameleonlike in its manifestations, and often aggravated by their ministrations, it did not fight by the Queens-bury Rules.

Medicine's flounderings suggest that hysteria proved something "other," the one that got away. Consensus never crystallized as to its nature and cause. In recent years, it has waltzed in and out of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual , the English-speaking world's authoritative psychiatric handbook. Disgruntled doctors have often proposed conceptual slum clearance and a fresh terminological start: Josef Babinski wanted to rename it "psychasthenia" or "pithiatism," Janet suggested "psychasthenia," and certain contemporary physicians prefer "Briquet's syndrome,"[29] all in the, surely vain, hope that old confusions were but word deep. As the shrewd reassessments of Alec Roy, Harold Merskey, Alan

Krohn, and others have made clear, medicine today remains deeply divided as to whether hysteria is a skeleton in the cupboard or a ghost in the machine; a phantom like "the spleen," or a bona fide disorder. And if authentic, is it organic or mental? A disease that has largely died out or been cured, or one camouflaging itself in colors ever new?[30]

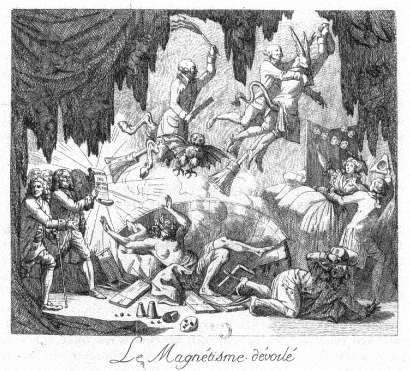

Such battles long since spilled over time's border into the terrain of history. A cast of heroes and villains from the past has been recruited to play key roles. Indeed, as Helen King established earlier in this volume, when Renaissance doctors first needed to develop the hysteria concept, high priority was given to manufacturing a pedigree going all the way back to Hippocrates.[31] Physicians have also turned to the past to exercise their skills in retrospective diagnosis: preferred readings of hysteria will, it is assumed, be vindicated if they lead to the identification of former outbreaks. After all (so argued nineteenth-century bio-medics), what is medical science if not an engine for discovering nature's universal laws, operating uniformly through time and space, in the past, present, and future? Thus Charcot declared in ringing tones that "L'Hystérie a toujours existé, en tous lieux et en tous temps."[32] In Les Demoniaques dans l'art (1887), jointly written with his colleague Antoine Richer, he contended that what benighted ages had mistaken for mystics and demoniacs were archetypically hysterics. By thus exposing the hysteria so long hidden from history, Charcot strengthened his claim to be, in the there-and-then as well as the here-and-now, the all-conquering "Napoleon of the neuroses." Further medical demystification of religious enthusiasm by D.-M. Bourneville and other intimates of the charcoterie helped mobilize the radical, anticlerical medical politics of the Third Republic.[33]

Psychiatrists such as Gregory Zilboorg subsequently developed these retrospective diagnoses of early modern demoniacs as sick people possessed, not by the devil, but by disease, as people fit, not for the flames, but for the couch. In propagating such views, analysts from Freud to present psychohistorians have presented themselves as pioneers of therapeutic methods and historical readings both enlightened and scientific.[34]

Historiography

And historians of hysteria have characteristically followed in their footsteps: it was no accident that the first substantial chronicles of hysteria were written by Charcotian protégés.[35] Such works have assumed that the annals of medical history, down the centuries and across the cul-

tures, point to outcrops of a disorder now identifiable as hysteria, and that the medical mission of understanding, classifying, and treating it can be recounted as a progression from superstition to science, ignorance to expertise, prejudice to psychoanalysis. The standard English-language history, Ilza Veith's Hysteria: The History of a Disease (1965), is wholly cast within this mold.[36]

As her title indicates, Veith's premise is that hysteria is an objective disease, the same the whole world over. It had been known to doctors—East and West—at least from 1800 B.C ., Veith contended, though it was the Greeks who had given it its name. Medieval Christendom's gestalt switch, treating psychosomatic symptoms as the stigmata of Satan, had entailed a gigantic regression.[37] Fortunately, far-sighted Renaissance physicians such as Johannes Weyer had recaptured hysteria from the theologians, seeing it as a disease, not a sin.

Even so, true understanding (and treatment) continued to be hamstrung by a fallacious medical materialism misconstruing hysteria as organic—standardly, an abnormality of the womb, or, in later centuries, of the nervous system and brain stem. Veith particularly deplored the "increasingly sterile and repetitive neurological basis that had emanated from Great Britain for nearly two hundred years," sparked, above all, by George Cheyne's "nervous" theory, whose "affectation and absurdities are such that it scarcely merits elaborate discussion"—even the Scottish iatromechanist's "references to his own distress," Veith uncharitably grumbled, "seem inconsequential."[38] Not least, she argued, somatic hypotheses had been marred by misogyny. Overall, such ideas were precisely the obstacles that, in Freud's view, had "so long stood in the way of [hysteria] being recognized as a psychical disorder."[39]

Fortunately, according to Veith, a counterinterpretation had emerged, albeit by fits and starts. Brave spirits such as Paracelsus, Edward Jorden, Thomas Sydenham, Franz Anton Mesmer, Philippe Pinel, Ernst von Feuchtersleben, and Robert Carter began to develop "an amazing amount of anticipation" of the insight—finally triumphant with Freud—that hysteria was psychogenic, the monster child of emotional trauma aggravated by bourgeois sexual repression, especially of females.[40] Thanks principally to Freud, this libidinal straitjacket had finally been flung off, leading to the disorder's demise in the present century: Veith's narration concluded with Freud.

It says something for the vitality of medical history that, twenty-five years later, Veith's recension appears hopelessly outdated. For one thing, hers was heroes-and-villains history, being particularly free with bouquets for those who "anticipated" Freud's psychosexual theory. Among these,

the mid-Victorian practitioner Robert Carter received her most fulsome floral tributes, for having effected "a greater stride forward" than "all the advances made since the beginning of its history."[41] This rosy interpretation of Carter grates, however, upon a modern generation primed on antipsychiatry and feminism. After all, it was precisely his judgment that hysteria was psychogenic that enabled Carter to indict hysterical women as not sick but swindlers, sunk in "moral obliquity," cynically exploiting the sick role to manipulate their families and getting perverse sexual kicks out of the repeated vaginal examinations they demanded. Carter, however, saw through their tricks and advocated subjecting them to ordeal by psychiatric exposure.[42] With Dora's case in mind, we might wryly agree with Veith that Carter did indeed "anticipate" Freud, but such a compliment would, of course, be backhanded, underlining that Freud too could be a misogynistic victim blamer and therapeutic bully. Faced with the deviousness of hysterics, Freud confided to Wilhelm Fliess his sympathy for the "harsh therapy of the witches' judges."[43]

More generally, Veith's "history of a disease"—indeed, of a "mental disease"[44] —conceived as a joust between benighted (somatic) theorists, who "retarded" comprehension, and their forward-looking psychological rivals, suffers from the stock shortcomings of wise-after-the-event Whiggism.[45] Past theorists are graded by the yardstick of Freud, whose theory is taken as the last word. With hindsight derived from the psychodynamic revolution, Veith organizes her history of hysteria around an essential tension between (wrong) somatogenic and (valid) psychogenic claims.

A radically different reading is offered by Thomas Szasz. For Szasz, hysteria is not a real disease, whose nature has been progressively cracked, but a myth forged by psychiatry for its own greater glory. Freud did not discover its secret; he manufactured its mythology.[46] Drawing upon varied intellectual traditions—logical positivism, Talcot Parsons's theory of the sick role, ethnomethodology, and the sociology of medical dominance—Szasz has made prominent, in his The Myth of Mental Illness ,[47] psychoanalysis's "conversion" of hysteria into a primary psychogenic "mental illness" marked by somatic conversion, the translation, as William R. D. Fairbairn put it, of a "personal problem" into a "bodily state."[48] "I was inclined," reflected Freud, "to look for a psychical origin for all symptoms in cases of hysteria."[49]

Exposing this as a strategy integral to a self-serving "manufacture of madness," Szasz counters with a corrosive philosophical critique. By thus privileging the psyche, Freud was in effect breathing new life into the

obsolete Cartesian dualism, resurrecting the old ghost in the machine, or rather, in the guise of the Unconscious, inventing the ghost in a ghost.[50] For Szasz, on the other hand, the expectation of finding the etiology of hysteria in body or mind, above all in some mental underworld, must be a lost cause, a dead end, a linguistic error, and an exercise in bad faith. For the "unconscious" is not a place or an organ but, at most, a metaphor; Freud stands arraigned of rather naively pictorializing the psyche in hydraulic and electrical terms, of reifying the fictive substance behind the substantive.[51]

Properly speaking, contends Szasz, hysteria is not a disease with origins to be excavated, but a behavior with meanings to be decoded. Social existence is a rule-governed game-playing ritual. The hysteric bends the rules and exploits their loopholes. Not illness but idiom (gestural more than verbal), hysteria pertains not to a Cartesian ontology but to a semiotics, being communication by complaints . Since the hysteric is engaged in social performances that follow certain expectations so as to defy others, the pertinent questions are not about the origins, but the conventions, of hysteria.[52]

Sidestepping mind/body dualisms, Szasz thus recasts hysteria as social performance, presenting problems of conduct, communication, and context. Freud believed mind/body dichotomies were real, though typically mystified, and attempted to crack them. Szasz dismisses these as questions mal posées , deriving (like Freud's "discovery" of the unconscious) from linguistic reification or bad faith, and he aims to reformulate them.

If idiosyncratic, Szasz's analysis is also a child of its time. Modern linguistic philosophy, behaviorism, and poststructuralism all depreciate the etiological quest: origins, authors, and intentions are discounted, systems, conventions, and meanings forefronted. Szasz does not, of course, expect that his paradigm-switch will magically switch off all the uncontrollable sobbing, fits, tantrums, and paralyses. But it offers alternative readings of such acts, while undermining expectations that tracking hysteria will lead to the source of the Nile, that is, the solution of the riddle of mind and body.[53]

Szasz's resolution of hysteria is bracing, but it is achieved at the cost of reducing its past to pantomime: his adoption of the language of game-playing turns everyone, sufferers and medics alike, into manipulative egoists. Illness is just a counter in a contest. So why embrace this dismissive, belittling view? It is because Szasz is at bottom an old-school medical materialist: disease is really disease only if it is organic.[54] Were hysteria—were any so-called mental illness—somatically based, it would have a real history (afflicting people, being investigated by physicians). Lacking organic "papers," its past, rather like those of transubstantiation

or of perpetual-motion engines, is a blot, a disgrace, a fiction, a tale of knaves and fools worthy of some philosophe's pen.

Thus, for equal but opposite reasons, Veith and Szasz both short-circuit hysteria's history. Veith (oddly like Charcot) feels obliged to trace it from the pharoahs to Freud; Szasz thinks the history of hysteria begins with Freud's psychodynamic empire building. Believing hysteria psychogenic, Veith recounts her "history of a disease" as the road to Freud. Believing disease must be somatic, Szasz paints hysteria's history as the pageant of a dream. Both approaches trivialize the intricate texture of hysteria down the ages, the true understanding of which must respect, not explain away, the enigmas of multifaceted, evanescent pain in a culture within which mind/body relations have been supercharged and devilishly problematic.

Yet Veith's and Szasz's polarized readings are, in their own way, highly exemplary, for they both highlight mind/body disputes in hysteria's etiology. Down the centuries, physicians long lamented how hysteria remained sphinxlike, because mind/body relations themselves proved a conundrum. Veith's desire to divide her protagonists into ("retarding") materialist and ("progressive") psychological camps is, however, misguided, for it freezes the rhetoric of the Freudian era and anachronistically backprojects it. Yet Szasz's mythic history, subserving his own debunking and liberating polemic, also cuts corners, above all by seemingly denying any significant developments before Freud. Many recent historians, especially Mark Micale,[55] have, by contrast, insisted on the enormous intricacy and indeterminacy of the story of hysteria. Above all, as will be explored below, it would be simplistic to imply that early theories were exclusively either somatogenic or psychogenic; most commonly they were attempts to dissect and plot the puzzling entente between the passions of the mind and the constitution of the body. Our story is thus not a matter of either/or but of both/and. And it is, above all, a history in which the very notions of mind and body, and the boundaries and bridges between them, were constantly being challenged and reconstituted.

Hence this chapter will focus on medical theorizings of mind/body pathologies. It will thus engage the metaphysics of hysteria, examining the theoretical underpinnings that made possible a succession of puzzles, problems, and solutions. The story of hysteria (I will argue) makes scant sense if restricted to internal, technical skirmishings over nerves and neurons, passions and pathogens. Far more was at stake, not least because, as Szasz has insisted, hysteria became an exemplary disease, the disorder that single-handedly launched psychoanalysis.

Small wonder this wider history is requisite, for the biomedical doc-

trines of body and brain, psyche and soma, have never been neutral post-mortem findings, hermetically sealed from the symbolic meanings accreting around sickness in daily experience, meanings of utmost significance for doctrines of human nature, gender relations, moral autonomy, legal responsibility, and the dignity of man.[56] Medicine's authority, its prized scientificity, may have rested upon its vaunted monopoly of expertise over the human organism, but its public appeal has equally hung upon its ability to attune its terms and tones to the popular ear. The historian of hysteria must, in short, bear in mind the wider determinants: changing ideas of man, morality and culture, and the politics of medicine in society.

Mind and Body: Medical Materialism and Hegemonic Idealism

I wish to explore a further dichotomy—Charcot's historical metaphysics juxtaposed against Freud's—to show its exemplary status for understanding the mind/body politics of hysteria.

To secure their credentials, many nineteenth-century medics proclaimed a powerful metahistory: Auguste Comte's scheme of the rise of thought, from the theological, via the metaphysical, up to the scientific plane.[57] As embraced by positivists, par excellence those in Charcot's circle, such a progressive schema implied that sickness had, at the dawn of civilization, been misattributed to otherworldly agencies (spirit possession, necromancy, etc.), subsequently being mystified into formulaic verbiage (humors, animal spirits, complexions) dissembling as explanations. Growing out of such mumbo jumbo, physicians had finally learned to ground their art in the nuts-and-bolts real-world of anatomy, physiology, and neurology.[58] Through abandoning myths for measurement, words for things, metaphysics for metabolism, medicine had at long last grasped the laws of nature, which would prove the prelude to effective therapeutics. According to Charcot (as will further be explored below), hysteria would be solved by pursuing the science of the body.

Freud, however, though Charcot's sometime student, cuts across the grain of this explanatory strategy—indeed, presents a case of ontogeny reversing phylogeny. The young Freud had been inducted into the Germanic school of neurophysiology, whose creed (paralleling the positivist) espoused the triple alliance of scientific method, medical materialism, and intellectual progress: explanations of the living had to be somatically grounded or they weren't science. Though initially endorsing this neurological idiom, Freud, in his own theorizings of neuroses and hysteria,

eventually adopted a thoroughgoing psychodynamic stance, eventually formulating a battery of mentalist neologisms—the unconscious, ego, id, super ego, death wish, and so on—which logical positivists have ever since derided as throwbacks to Comte's "metaphysical" stage.[59] In tandem, Freud's therapeutics moved from drugs (e.g., cocaine), through hands-on, pressure-point hypnosis, to the purely psychical (free speech associations).[60] Freud, some would say, was a kind of mental recidivist.

In thus privileging the mind as primum mobile , Freud challenged biomedicine's bottom line—and regarded himself as victimized for his pains, while energetically milking his self-image as a persecuted heretic.[61] Yet, by so doing, he has won a standing ovation from twentieth-century high culture, predisposed to believe that explanations of human behavior predicated upon the workings of the mind , however dark and devious, must be more profound, humane, insightful, true, and titillating even, than any formulated in biochemical or genetic categories.[62] As we have seen, Veith herself assumed that once Freud finally discovered hysteria to be psychogenic , the curtain could be brought down to rapturous applause. Psychoanalysis's "discovery of the unconscious,"[63] unlocking the secrets of human desires, both normal and pathological, remains one of the foundation myths of modernity.

In addressing the rival paradigms of fin de siècle hysteria, we thus find a cross fire—the one scientific, ratifying positivist laws of the organism; the other convinced that meaningful explanations of action must derive from an ontology of the psyche. This is an instructive dichotomy (biologism/mentalism), reproducing in a nutshell two clashing configurations of Western thought.

On the one hand, psychoanalysis's mentalism is underpinned by the pervasive and prestigious Idealism, philosophized by Platonism and the Cartesian cogito , long underwritten by Christian theology, and, in secular garb, still the informal metaphysical foundations of the humanities in C. P. Snow's "two cultures" dichotomy. Such hierarchical, dualistic models programmatically set mind over matter, thinking over being, nurture over nature, head over hand, as higher over lower, the mental being ontologically superior to the corporeal. Macrocosmically, brute matter was subordinate to the Divine Mind or Idea, acting through immaterial agencies; likewise, microcosmically, the achievement of mens sana in corpore sano required that mind, will, or spirit must command base flesh—and, as Theodor Adorno, Norbert Elias, Foucault, and others have argued, the civilizing process, that celebrated march of mind demanded by capitalism, long entailed the intensification of body-disciplining techniques.[64] Within this view, sickness is regarded (like crime, vice, or sin)

as the aftermath of reason losing control, either because the metabolism itself has been highjacked (for instance, in the delirium of fever), or when civil war erupts within the mind itself, leading to the "mind forg'd manacles" of mental illness.[65]

Freud torpedoed theology, wrestled with philosophy, but loved science. His views of the drives and the unconscious naturally could not countenance the Christian-Platonic divine-right monarchy of Pure Reason: it is, after all, the mission of psychoanalysis to debunk such illusions (purity indeed!) as projections, sublimations, and mystifications.[66] Nor could he accept at face value the doctrinaire distinctions between freedom and necessity, virtue and appetite, love and libido, and so on postulated by philosophical Idealism. These—like so many other values—were not eternal verities, gifts from the gods, but problematic, sublimated, even morbid, constructs ("defences"). Nevertheless, the thrust of Freudian psychodynamics—his point of departure from Wilhelm Brücke, Charcot, and Fliess, and then from some of his own epigoni such as Wilhelm Reich—lay in denying the sufficiency of biology or heredity to explain complexities of behavior, healthy or morbid. In the case of complexes, the body becomes the battleground for struggles masterminded elsewhere.[67]

Freud was deeply torn. Clinical experience led to his giving sovereignty to the psyche. Yet herein lay a profound irony, for he was also, as Peter Gay has aptly emphasized, a child of the old Enlightenment itch to smash Idealism, unveiling it as the secret agent of false consciousness, repression, and priestcraft.[68] He was, moreover, heir, by training and temper, to the crusading medical materialism and biophysics of his youthful heroes—Hermann Helmholtz, Theodor Meynert, and his mentor, Brücke, not to mention Charcot himself. For such luminaries, as for the Freud of the abandoned 1895 Project, doing science meant translating behavior into biology, consciousness into neurology, random experience into objective laws. And in pursuing such positivist approaches, nineteenth-century bioscientists were, as Lain Entralgo has stressed, further endorsing the disposition, from the Greeks onward, in what was significantly titled "physick," to enshrine the body as the ultimate "reality principle."[69]

The body provides sufficient explanation of its own behavior. Diseases are in and of the organism. They are caused by some fluid imbalance, physical lesion, internal dislocation, "seed" (or foreign body), excess, deficiency, or blockage; material therapeutics—drugs and surgery—will relieve or cure. Abandon such home truths, such professional articles of faith, and the autonomy and jurisdiction of biomedical science and clinical practice melt like May mist. Once it were admitted that

sickness could not be sufficiently explained in and through the body—unless it could be said, at some level, "in the beginning, was the body"—medicine would forfeit its title as a master discipline, grounded upon prized clinicoscientific expertise. Unless sickness is translatable into the lingo of lesions and laws, why should not anyone—priests, philosophers, charlatans, sufferers—treat it as well as a doctor? Herein lies the explanation of why scientific medicine committed itself, from the Renaissance, to evermore minute anatomical and physiological investigations, even though the therapeutic payoffs long remained unconvincing.

Yet this strategy for ratifying professional credentials through a science of the body naturally ran the risk of counterproductivity. For, in a culture-at-large in which Idealism was hegemonic, medicine thereby exposed itself to the charge that its incomparable organic expertise was purchased at the price of higher dignity: a liability perfectly summed up in Coleridge's damnation of the doctors for their debasing somatism: "They are shallow animals," judged the ardent Platonist, "having always employed their minds about Body and Gut, they imagine that in the whole system of things there is nothing but Gut and Body."[70]

The program widely, if tacitly, adopted by medicine since the scientific revolution of locating disease explanations within the body seemed unexceptionable when addressing conspicuous conditions—tumors or dropsy, for instance—involving physical abnormalities. It has proved more problematic, however, where pain flares seemingly independently of manifest external lesions: even today medicine is embarrassed when faced with common complaints such as nervous exhaustion, stress, or addiction. And medicine's claims encounter special strain in cases where disturbances are sporadic and seemingly irrational. It is in these borderland areas, the fields of so-called functional and nervous disorders where sickness experience wants secure somatic anchorage, that medical credit is least convincing. If suffering lacks lesions and localizations, why should it be medicine's province at all? After all, leading critics from within the profession, notably Thomas Szasz, have invoked medicine's cherished criteria (logical positivism and methodological materialism) to contend that, since physick's kingdom is the body, and medicine is thus definitionally organic (else it is a chimera), the very idea of primary mental illness should be struck off the register as a category error, a misleading metaphor—or, worse, a pious fraud, smacking of professional bad faith.[71] Medicine has jurisdiction over the somatic, but who authorized its writ to run one step beyond? As G. S. Rousseau's essay has shown, physicians long ago hoisted their flag over hysteria; but the terra incognita has ever proved remarkably resistant to assured colonization.

Thus ours has been a civilization in which, in an ideological shadow

play of the sociopolitical order, hegemonic Idealism has traditionally enthroned mind over what theology denigrated as the "flesh," forever too, too solid and sullied.[72] At the same time, medicine, by embracing (proto)-positivist notions of science and professional territorial imperatives, has espoused a praxis affording it control over the organic. Superficially it might seem that these two drives—enshrining spirit, yet making matter the foundation stone of science—are radically incommensurable. Yet doctors live in the world and medicine needs to be credit-worthy; or, in other words, accommodations have ever been reached, or ensure that cultural idealism and medical materialism work in broad harmony, rather than on a collision course.[73]

Medicine, philosophy, and theology developed thought-packages designed to demarcate the domains and specify the pathways of mind and matter. Thus, so ran long-standing prescriptions, the rules of health required that mind must be in the saddle, enacting the precepts of philosophers and preachers. Whenever the reign of reason is challenged, when brute flesh mutinies, the resultant state is sickness, and then the mentor makes way for the doctor. In any case, and giving the lie to Coleridge's slur, physicians themselves, time out of mind, have prescribed. liberal doses of willpower as the recipe for "whole person" well-being: be healthy-minded, think positive, exercise self-control. As Michael Clark has brilliantly shown, late Victorian doctors characterized the sound, responsible person as one who tempered the will and disciplined the body, channeling the energies, like a true Aristotelian, into healthy public activity. By contrast, the hypochondriac or degenerate was trapped in morbid introspection, prisoner, in Henry Maudsley's graphic phrase, of the "tyranny of organization."[74]

So cultural Idealism and medical materialism, though perhaps worlds apart, have rarely been daggers drawn. Each assigned roles to the other within its own play. Even medical materialists such as Julien de La Mettrie recognized that, taken to extremes, to reduce man to nothing but l'homme machine would be self-disconfirming, while no less an idealist than Bishop George Berkeley did not hesitate to tout tar-water as a panacea.[75] Thus cultural Platonism and medical materialism are best regarded as uncomfortable matrimonial partners, who have engaged in partial cooperation to frame images of the constitution of man, the dance of soma and psyche, the triangle of sanity, salubrity, and sickness, and, not least, of the politics of the moral/physical interface.[76]

For doctors have to operate in the public domain, jostling with rivals in expertise and authority, and their services ultimately have to please paying patients. So medicine cannot afford to bury itself in sprains and pains but must engage with wider issues—religious, ethical, social, and

cultural. The public wants from doctors explanations no less than medications; society looks to the profession for exhortation and excuses. Medicine is called upon to supply stories about the nature of man and the order of things. Moreover, because medicine has never enjoyed monopoly—nor has it been monolithic; it has been divided within itself—it has developed multiple strategies for securing its place in the sun.

It would, in fine, be myopic to treat medicine as a limited technical enterprise. This is especially so when we are faced with interpreting the peculiarities of hysteria, a disorder that, as indicated, dramatically rose and fell between the Renaissance and the First World War, a trajectory indubitably linked to larger cultural determinants affecting patients and practitioners alike.

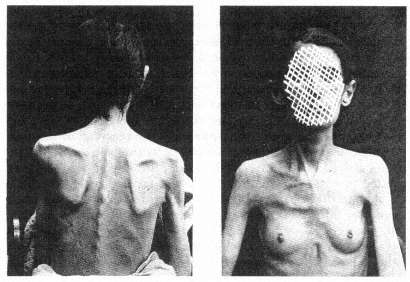

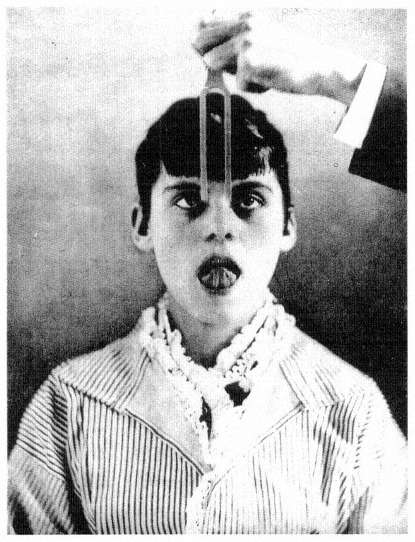

Hysteria presented doctors with a tease, a trial, and a break. The hysteria diagnosis, critics griped, was the most egregious medical hocus-pocus, attached to symptom clusters physicians could not impute to some more regular cause. The symptoms were heterogeneous, bizarre, and unpredictable: pains in the genitals and abdomen, shooting top to toe, or rising into the thorax and producing constrictions around the throat (globus hystericus ); breathing irregularities; twitchings, tics, and spasms; mounting anxiety and emotional outbursts, breathlessness, and floods of tears; more acute seizures, paralyses, convulsions, hemiplagias, or catalepsy—any or all of which might ring the changes in dizzying succession and often with no obvious organic source. Faced with such symptoms, what was to be done? The mystery condition (spake the cynics) was wrapped up as "hysteria." Such, according to the mid-seventeenth-century neurologist Thomas Willis, was the physicians' fig leaf worn to hide their cognitive shame:

[W]hen at any time a sickness happens in a Woman's Body, of an unusual manner, or more occult original, so that its causes lie hid, and a Curatory indication is altogether uncertain. . . . we declare it to be something hysterical . . . which oftentimes is only the subterfuge of ignorance.[77]

Evidently, things did not improve. A full century later, William Buchan still felt obliged to dub hysteria the "reproach of medicine," since the "physician . . . is at a loss to account for the symptom."[78] Was hysteria then just a will-o'-the-wisp, a fabulous beast or phantom? Or was it an authentic malady, whose essence lay in having no essence, being prodigiously protean, the masquerading malady, mimicking all others?[79] And if hysteria were such a desperado, was it truly not a disease at all, but some kind of Frankenstein's monster, a brain-child of the medical imagination finally turned upon its own creators?

In the light of these grander issues—the problems of medicine's continued attempt to confirm its place within the wider culture, the mind/body ambivalence of hysteria, the brevity of hysteria's heyday, and the construal of hysteria as an anomalous monster disease—it can hardly be illuminating to write, as did Veith, about the "history of a disease" in the same manner that one might sensibly survey smallpox and its medical eradication. It would be doubly misleading to imply that medical advances successively laid bare the true roles played in the etiology of hysteria by mind and body; for, as just suggested, mind and body are not themselves cast-iron categories, but best seen as representations negotiated between culture, medicine, and society.[80] Hence, in the remainder of this chapter, I shall explore some different meanings successively assumed by hysteria, in a world in which medicine was battling to extend its sway.

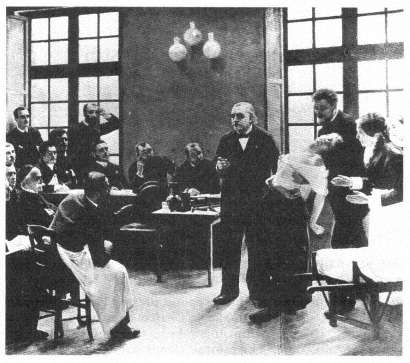

My account will emphasize the initiatives of medicine. Not because I believe that doctors had unique special insight into the condition,[81] or, contrariwise, that hysteria was cynically manufactured by a malign medical mafia. I do so, rather, believing that, like invisible ink when heat is applied, hysteria was a condition chiefly rendered visible by the medical presence. Without the calling of medical witnesses to witch trials, early modern physicians would rarely have pronounced upon these bizarre behaviors. Without the leisured sufferer whose purse spelled good times for private practice, Enlightenment physicians would not have had a tale to tell of nervousness. Without confinement in the Salpêtrière hospital in the proximity of epileptics, and, above all, without the electric atmosphere of Charcot's clinic, Blanche Wittmann and other stars of hysteria would have wasted their swoonings on the desert air.[82] Robert Carter, who was cynical about those "actresses," reflected that nature knew no such being as a solitary hysteric: hysteria was a public complaint presupposing an audience—mass hysteria definitionally so.[83] Was hysteria, then, purely iatrogenic, or, at least, as Eliot Slater would put it, "a disorder of the doctor-patient relationship"?[84] Maybe, though it would be more judicious to say that the nineteenth century was hysteria's golden age precisely because it was then that the moral presence of the doctor became normative as never before in regulating intimate lives.

Continuities: Toward Nineteenth-Century Nervousness

As Rousseau showed in the previous chapter, Enlightenment sensibilities were confronted with actions and sufferings not easily compatible with

vaunted paradigms of conduct or classifications of disease. The appearance of such alienation and irrationality has commonly been blamed, by modern countercultural critics, upon the dualistic doctrine of man proclaimed by the new philosophy, above all the Cartesian severed head and divided self, derived from the absolute rule of the cogito in the age of reason.[85] It is possible to take a view more sympathetic to eighteenth-century structures of feeling. The new availability of a plurality of models of living (Christian, civic humanist, individualist, scientific, and so forth) perhaps afforded welcome psychological Lebensraum to those—for instance, members of the newly emergent intelligentsia—who did not fit easily into rigid prescriptions. Dualistic models and multiple prototypes allowed a certain indeterminacy, or psychological je ne sais quoi , to be built into the makeup of modern man, allowing the accommodation of eccentricity and difference.[86]

Such margins of tolerance were sorely needed. For, as the Enlightenment era relaxed religious requirements, it was also applying intenser personal strains. Its exhausting commitment to the life of intelligence, its demand for politeness, and its relentless pressures for self-awareness and-realization, spelled more stressful standards of behavior, and hence highlighted their obverse: abnormality. In the rarefied atmospheres of sophisticated courtliness and brilliant urbanity, the body was required to be disciplined and drilled, yet also displayed. Inner sensibilities had to find expression at the tea table or in the salon through refined, subtle, and often veiled codes of etiquette, revealing but concealing through actions compelled to speak louder than words. The lingua franca for negotiating such repression-expression tensions lay in nervousness, a body language ultra flexible, nuanced, and ambivalent, yet brittle and fitful.

For life lived through the idioms of nervous sensibility carried high risks. Want of nerve betrayed effeminacy; want of nerves , by contrast, exposed plebeian dullness; yet volatile excitability could be too much of a good thing, a lapse of tact, culminating in hysterical crises. A golden mean—poised decorum spiced with idiosyncratic difference—was the goal. Achievement of this hazardous role adjustment, this accommodation between the hypervisible narcissistic individual and a society demanding Chesterfieldian conformism, was perhaps facilitated by precisely that divided Cartesian self so often berated by modern critics. Such a dualism—the man-behind-the-mask playing out the ontology, of the ghost in the machine—allowed a certain distance, a disowning, a usable tension between self and body. Diderot, Sterne, Casanova, and Rousseau all demonstrated, through their lives and writings, the rich potential for

dramatic self-expression afforded to the "new person" by the novel polysemic idioms of impulse, feeling, imagination, nerves, and, ultimately, hysteria.[87]

Enlightenment thinkers professed bafflement at the Sphinxian riddles of psyche/soma affinities. "The action of the mind on the body, and of the body on the mind," noted a leading authority on madness, "after all that has been written, is as little understood, as it is universally felt."[88] This ontological equivocation, this suspension of judgment, surely enhanced that respect with which the post-Sydenham hysteric was treated in a private practice milieu in which, as Nicholas Jewson has stressed, some rough-and-ready parity governed patient/practitioner relationships.[89] Thus, that great clinician, William Heberden, a man utterly au fait with the symptoms, saw hysteria as a condition all too readily provoked by the "slightest affection of the sense or fancy, beginning with some uneasiness of the stomach or bowels." "Hypochondriac men and hysteric women" suffered acidities, wind, and choking, leading to "giddiness, confusion, stupidity, inattention, forgetfulness, and irresolution," all proof that the "animal functions are no longer under proper command."[90] But, a man of his time, he was loath to dogmatize as to the root cause. For,

our great ignorance of the connexion and sympathies of body and mind, and also of the animal powers, which are exerted in a manner not to be explained by the common laws of inanimate matter, makes a great difficulty in the history of all distempers, and particularly of this. For hypochondriac and hysteric complaints seem to belong wholly to these unknown parts of the human composition.[91]

Like most contemporary clinicians, Heberden was prepared to live with the mystery visitor. "I would by no means be understood, by any thing which I have said, to represent the sufferings of hypochondriac and hysteric patients as imaginary; for I doubt not their arising from as real a cause as any other distemper."[92]

In other words, the historical sociology of Enlightenment hysteria is defined by the clinical encounter between the sensitive patient and the sympathetic physician. The ambience was elitist, and it was, in principle at least, unisex. Ridiculing uterine theories of hysteria as anatomical moonshine, Richard Blackmore had concluded that "the Symptoms that disturb the Operations of the Mind and Imagination in Hysterick Women"—and by these symptoms he meant "Fluctuations of Judgment, and swift Turns in forming and reversing of Opinions and Resolutions, Inconstancy, Timidity, Absence of Mind, want of self-determining

power, Inattention, Incogitancy, Diffidence, Suspicion, and an Aptness to take well-meant Things amiss"—these, he insisted, "are the same with those in Hypochondriacal Men."[93] How could an age nailing its colors to the mast of universal reason, a culture whose moral vocabulary turned upon sense and sensibility, define hysteria as the malaise of the mucous membrane?

This clinical rapport forged in the century after Sydenham between fashionable doctor and his moneyed patients did not cease in 1800: far from it. Nineteenth-century medicine presents a Frithian panorama of well-to-do, time-to-kill, twitchy types of both sexes being diagnosed as hysterical, or perhaps by one of its increasingly used euphemistic aliases, such as "neurasthenic,"[94] and being treated, by general practitioners and specialist nerve doctors alike, with a cornucopia of drugs and tonics, moral and behavioral support, indulgence, rest, regimen, and what-you-will—in ways that surely would have won the imprimatur of Samuel Tissot, Theodore Tronchin, or Heberden.[95] Such continuity may show that Victorian medicine failed in its quest for the promised specific for hysteria. But it would be more to the point to emphasize that, from Giorgio Baglivi to George Beard, the canny clinician knew that the hysteric's prime needs were for attention, escape, protection, rest, recuperation, reinforcement—physical, moral, and mental alike. The least plausible indictment against either Mandeville or Weir Mitchell is that they tried to force hysteria onto some Procrustean bed. For them, the protean language of nerves permitted the sufferer to bespeak his or her own hysteria diagnosis as a nonstigmatizing cloak of disorder. It was Mitchell who was wont to speak of "mysteria."[96]

In the nineteenth century, the rest home, clinic, and sanatorium supplemented the spa-resort to provide new recuperative sites for the familiar nervous complaints of the rich. Their therapeutic rationale, however, was old wine in new bottles. Nerve doctors continued to emphasize the force field of the physical, emotional, and intellectual in precipitating hysteria (or, later, neuropathy, neurasthenia, etc.); they defined hysteria, formally at least, as gender nonspecific, independent of gynecological etiology. There was life still in the old Enlightenment idiom of the nerves. Above all, by cushioning neurasthenic patients within a somatizing diagnostics of nervous collapse, nervous debility, gastric weakness, dyspepsia, atonicity, spinal inflammation, migraine, and so forth, fashionable doctors could forestall suspicions that their respectable patients were either half mad or malingering sociopaths.[97]

Not least, "nerves" precluded moral blame, by hinting at a pathology not even primarily personal, but social, a Zeitgeist disease. Eighteenth-

century nerve doctors tended to indict cultural volatility: salon sophisticates were victims of exquisitely vertiginous life-styles that sapped the nerves. By contrast, in later recensions of the diseases of civilization, High Victorian therapists on both sides of the Atlantic pointed accusing fingers at the pitiless competition of market society. As Francis Gosling has shown, George Beard and Weir Mitchell argued that career strains in the business rat race devitalized young achievers; brain-fagged by stress and tension in the cockpit of commerce, they ended up nervous wrecks, their psychological capital overtaxed. Cerebral circuits suffered overload, mental machinery blew fuses, batteries ran down, brains were bankrupted: such metaphors, borrowed from physics and engineering, were reminders that disorders were physical, offering convincing explanations why go-getting all-American Yale graduates like Clifford Beers should suffer nervous breakdowns no less than their delicate and devoted sisters.[98]

Such decorous somatizing also permitted physicians to exhibit dazzling therapeutic machineries, targeted at bodily recuperation: baths and douches, passive "exercise," massage, custom-built diets programmed to make weight, fat, and blood; regimes of walking, games, and gym; occupational therapy, water treatments, electrical stimuli, relaxation, routine, and so forth. This paraphernalia of remedial technologies obviously spelled good business for residential clinical directors. Strategically, such routines were said to benefit patients by deflecting them from morbid self-awareness, training attention more beneficially elsewhere.

For nineteenth-century physicians began to voice fears of morbid introspection, that hysterical spiral arising from patients dwelling upon their disorders.[99] Precepts for healthy living widely canvassed—by sages such as John Stuart Mill and Thomas Carlyle no less than medical gurus—deplored egoistic preoccupation as the road to ruin, to suicide even, and advised consciousness-obliterating, outgoing activity.[100] For the hysteric was typically regarded as the narcissist or introvert. From her Freudian viewpoint, Veith has blamed Weir Mitchell for not encouraging his rest-cure convalescents to talk their psychosexual problems through, implying that this silence may have been due to prudery. One suspects, in truth, the doctor's reticence reflects neither puritanism nor shallowness, but savvy: a conviction that some matters were better left latent, lest they inflame morbid tendencies.[101]

"Only when bodily functions are deranged," warned the mid-Victorian British physician Bevan Lewis, do "we become . . . conscious of the existence of our organs."[102] In his caution about consciousness, Lewis was of a mind with the leaders of British practice—Charles Mercier,

David Skae, Henry Maudsley, and Thomas Clouston—who saw hysteria as the penalty for excessive introspection, especially when accompanied by a- or anti-social dispositions and, worse still, by auto-erotism.[103] It was, consequentially, dangerous to discuss such dispositions freely with patients, lest this encourage further morbid egoism and attention-seeking, and all the attendant train of self-absorption, daydreaming, reverie, and solitary and sedentary habits. Prompted to dwell upon herself, Maudsley feared, the hysteric would most likely sink into solipsistic moral insanity or imbecility;[104] for, as the patient progressively abandoned her power of will—"a characteristic symptom of hysteria in all its protean forms"—she would fall into "moral perversion," losing

more and more of her energy and self-control, becoming capriciously fanciful about her health, imagining or feigning strange diseases, and keeping up the delusion or the imposture with a pertinacity that might seem incredible, getting more and more impatient of the advice and interference of others, and indifferent to the interests and duties of her position.[105]

For their own sakes, therefore, patients must be taken "out of themselves"—through therapeutic hobbies, exercise, and sociability. Thus Sir William Bradshaw, the society physician in Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway , notoriously instructs the shell-shocked war victim Septimus Smith to pull himself together and cultivate a sense of proportion. Through the caricature of this pompous ass, Woolf expressed her contempt for such London physicians as Sir George Savage and Maurice Craig, who treated her own nervous collapses with the moral anodyne of the rest cure. Yet Woolf herself was no less scathing, in a terribly English way, about the asininities of sex-on-the-brain Germanic psychiatrists. There is no sign that she favored having Freudian "mind doctors" open Freud-ian windows onto her psyche.[106]

In short, powerful currents through the nineteenth century and beyond continued to class hysteria as a disease of nervous organization. Doctors fixed upon physical symptoms, and treated them with physical means, steering clear of too much skirmishing with, or stirring up, the mind. If blinkered and complacent, such approaches were not necessarily obtuse. The contrasting protocols of Charcot's Tuesday Clinic[107] and the Freudian couch arguably hysterized hysteria, as one might douse a fire with gasoline. Yet if continuities with the Enlightenment may be seen, there are gear shifts too; above all, perhaps, a certain waning of medical sympathy for the nervous hysteric in the generations after 1800, thanks to a sterner Evangelical prizing of self-reliance.[108] If the Enlightenment indulged a certain fascination for idiosyncracy, Victorian

mores took their stand against the egoistic sociopath. To these sociopaths we turn.

Change: Women, Body, and Scientific Medicine

Concentrating on continuities with the past risks skewing nineteenth-century outlooks on hysteria. It was, all agree, hysteria's belle epoque , thanks above all to the startling emergence and convergence of mutually reinforcing conditions: a profound accentuation of the "woman question," coterminous with an evidently not unrelated expansion in organized medicine.

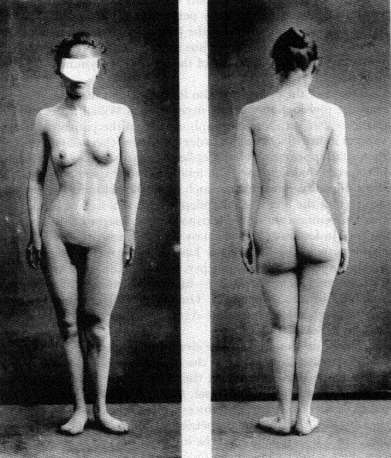

As Elaine Showalter fully explores in chapter 4, the question of feminine nature became a burning issue. Romanticism rang the changes on the paradoxes: wife and whore, femme fragile and femme fatale , weak but wanton—woman, it seemed, was an appallingly irresistible cocktail of innocence and morbid sexuality.[109] Bram Dijkstra, among others, has traced the sensationalization of that mythology toward the turn of the century.[110] In the shadow of such stereotypes, women experienced profound conflicts over rival ideals and expectations.[111] To hook a husband, a woman had to be childlike and dependent, yet also a tower of strength as the household manager of that great moral engine, the family, and robust enough to survive innumerable pregnancies. Wives had to be pure, yet pleasing, or risk being supplanted by the "other woman." Hence they had to develop their talents, yet intellectual aspirations were censured as unnatural, imperiling their manifest biological destiny as willing wombs. And if, stupefied by such pressures, paradoxes, and prohibitions, women showed signs of bewilderment or bridling, what did this prove but that they were spoiled, difficult, and capricious, further proof of the necessity for male and medical control? When proto-feminist protest mounted, it gave further evidence to those who saw hysteria as the root of all female activism. History, anatomy, destiny, evolution—all were conscripted to clamp women in their place.[112]

And so, of course, as fine feminist scholarship has shown, was medicine.[113] Yet the medical profession itself was in the toils of traumatic transformation. Space limits here preclude any adequate exploration of the upheavals in the internal organization and public facade of medicine during the nineteenth century, but a few developments must be mentioned, playing as they did key parts in reshaping hysteria.

Amid the throng of professional groups competing for recognition and rewards, medicine contributed noisily to the clangor, frantically asserting its own unique vocation. Doctors sought fighter professional orga-

nization and public privileges. Teaching and research assumed greater institutionalization in university and laboratory. And, thanks to such developments, medical discourse became increasingly directed to professional peers. With new ladders of advancement, and the expansion of research schools and scientific circles, professional esprit de corps grew commensurably, entailing a certain displacement of the patient, who was increasingly downgraded to an object of "the medical gaze." All such changes had, as we shall see, profound implications for the hysteric.[114]

Overpopulated, insecure, but ambitious, medicine fractured into a proliferation of subdisciplines, with new specialties multiplying and vying for funds and fame. As Ornella Moscucci has demonstrated, obstetrics and gynecology pioneered identities of their own, staking out the new terrain of women's medicine. Neurology took shape as a specialty; Russell Maulitz has traced the rise of pathology. Public health came of age, and alliances between the social sciences and the emergent specialties of organic chemistry and bacteriology helped to forge modern epidemiology. Psychiatry blossomed, colonizing its own locations, above all, the asylum and the university polyclinic.[115]

And all such heightened division of labor led to different schools, national groups, and subspecialisms vaunting their own cognitive claims: in some cases, basic science, in others, clinical experience or laboratory experimentation, keyed to the microscope. L. S. Jacyna has stressed the espousal by professional medics of ideologies of scientific naturalism, centered on the laws of life.[116]

Nineteenth-century medicine reoriented itself beyond the sickbed into the clinic: the vast, investigative teaching hospital, equipped with advanced patho-anatomical facilities and a never-failing supply of experimental subjects. At the same time, with the emergence of the industrial state, medicine also found itself enjoying greater interaction with sociopolitical institutions. Examining vast disease populations in their new public capacity, physicians had to confront fresh questions: latency, disposition, contagion, diathesis, constitution, and inheritance.[117]

In short, scientific medicine flexed its muscles and spread its wings. It was courted by the public; it craved official authorization. Hence, doctors made bold to become scientific policymakers for the new age. The questions they addressed—matters of hygiene, efficiency, sanity, race, sexuality, morality, criminal liability, and so forth—were inevitably morally charged; many physicians claimed medicine as the very cornerstone of public morals. And so physicians shouldered an ever greater regulatory role, acting as brokers and adjudicators for state, judiciary, and the family. Turning technical expertise into social and moral directives,

medicine spoke out upon social order and social pathology, progress, and degeneration. As will now be seen, new medical specialties claimed jurisdiction over hysteria, and made it yield moral messages to slake, or stoke, Victorian anxieties.[118]

Problem Women: Gynecology and Hysteria

As Thomas Laqueur has contended, research in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries into human sexuality did not resolve the mystery of woman, but deepened it. The more that was discovered, however tentatively and tardily, about menstruation and conception, the more medical science confirmed the truth that hegemonic male culture was independently affirming: women were different .[119] Traditional Greek-derived biomedical teachings had represented the female reproductive apparatus as an inferior, imperfect inversion of the male. But during the eighteenth century and beyond, medicine and culture were abandoning that view and combining to reconstruct women as radically other .[120] And not merely other, but bizarre.

It had become acknowledged that, contradicting medical teachings going back to Hippocrates, female orgasm was unnecessary for conception. Investigations into ovulation also appeared to show that menstruation in women, unlike other mammals, occurred independently of libidinal excitation. In short, the relationship between erotic stimulus on the one hand, and conception on the other, became utterly (and uniquely) problematic. Female sexuality thus seemed, from the viewpoint of research into generation, a mystery, apparently biologically superfluous, and perhaps even pathological.[121]

Pontificating upon the riddles of female sexuality became the stock-in-trade of emergent gynecology. Elbowing aside "ignorant midwives" and the much-mocked accoucheurs , specialist surgeon-gynecologists made their bid to pass themselves off as more than mere operators: being rather experts, qualified to hold forth on the overpowering role of reproduction in determining female life patterns, in a set of scientific discourses in which womb became a synecdoche for woman.[122] Nineteenth-century medicine, claimed Foucault, forged a new hysterization of women's bodies. This was precisely the achievement of gynecology, largely backed by the equally junior disciplines of sexology and psychological medicine, against the backdrop, just sketched, of the establishment of specialized, scientific medicine.[123]

In a context of patriarchal values ultra-suspicious of female sexuality,[124] gynecologists set about designating the physiology and pathology

of this perplexing being. Once the chasm between arousal and conception had been established, female libido—so volatile, capricious, even rampaging—was revealed as inherently dysfunctional, dangerous even. So why the peculiar sensitivities of clitoris and vagina, all too susceptible to physiological and emotional disturbance? Was not even the uterus itself troublesome beyond the demands of childbearing? Were not women enslaved by their generative organs? And if so, what was to be done? Confronted with streams of female patients—many tortured with internal pain, others dejected, still others "delinquent"—these were the problems upon which the growing corps of women's disease specialists built their platform.

The answers offered by emergent gynecology portrayed women's health as desperately womb-dependent. Since the very raison d'être of the female lay in procreation,[125] properly directed thereto, erotic arousal had a certain value, within the walled garden of matrimony. Yet what of the risk of arousal among adolescent girls, spinsters, and widows? Abstinence was socially expected, yet continence had its quandaries, leading to chlorosis, wasting conditions, and emotional waywardness.[126] Frustration fueled fantasies and could lead to masturbation, an activity imperiling health—physical, moral, and mental.[127] In short, the female reproductive system was so precariously poised that almost any irregularity, whether excitation or repression, was sure to provoke hysteriform disorders.

Hysteria had ever been regarded as the charade of disease.[128] Now doctors feared it as eros in disguise. Its swoonings, jerks, convulsions, and panting blatantly simulated sexuality, affording surrogate outlets and relief, while the sufferer escaped the stigma of lubricity. Not least, in the throes of a fit, the hysteric was bound to be touched, pampered, and subjected to medical examination and treatment, all of which nineteenth-century doctors regarded as erotically gratifying.[129]

Gynecology and psychophysiology thus joined forces to make female sexuality problematic, highlighting the role of the sexual organs in provoking hysterical conditions widely believed to precipitate moral insanity. "Convulsions . . . in early life," judged the top late Victorian psychiatrist, Henry Maudsley, were indices of the "insane temperament," even in subjects not yet actually insane.[130] Such precocious, displaced eroticism could trigger long-term disturbances.

Early in the century, psychiatrists had pinpointed the links between menstrual abnormalities and hysteria. John Haslam, apothecary at Bethlem Hospital, observed that in "females who become insane, the disease is often connected with the peculiarities of their sex."[131] In a similar

vein, the influential psychiatric spokesman, George Man Burrows, drew attention to "various sanguiferous discharges, whether periodical, occasional, or accidental," all of which "greatly influence the functions of the mind."[132] Herein, argued Burrows, lay the key to female troubles, for "every body of the least experience must be sensible of the influence of menstruation on the operations of the mind"—it was, he judged, no less than the "moral and physical barometer of the female constitution."[133] Burrows tendered a physiological explanation based upon "the due equilibrium of the vascular and nervous systems":

If the balance be disturbed, so likewise will be the uterine action and periodical discharge; though it does not follow that the mind always sympathises with its irregularities so as to disturb the cerebral functions. Yet the functions of the brain are so intimately connected with the uterine system, that the interruption of any one process which the latter has to perform in the human economy may implicate the former.[134]

Ripeness for childbearing was the mark of the healthy woman. Hence, Burrows emphasized, were menstruation interrupted, "the seeds of various disorders are sown; and especially where any predisposition obtains, the hazard of insanity is imminent."[135]

Equally, he judged, local genital and uterine irritations would generate "those phantasies called longings, which are decided perversions or aberrations of the judgment, though perhaps the simplest modifications of intellectual derangement."[136] What was the explanation?

These anomalous feelings have been referred to uterine irritation from mere gravitation, and so they may be; but they first induce a greater determination of blood to the uterus and its contents, and then to the brain, through the reciprocal connexion and action existing between the two organs.[137]

It was two-way traffic. Amenorrhea was sometimes "a cause of insanity,"[138] but, reciprocally, "cerebral disturbance" could itself cause "menstrual obstruction,"[139] further exacerbating mental disorder, for "terror, the sudden application of cold, etc., have occasioned the instant cessation of the menses, upon which severe cerebral affections, or instant insanity, has supervened."[140]

In line with the times, Burrows also blamed menopause for severe female disturbance. Once again, he emphasized, the primary change was physiological:

The whole economy of the constitution at that epoch again undergoes a revolution. . . . There is neither so much vital nor mental energy to resist

the effects of the various adverse circumstances which it is the lot of most to meet with in the interval between puberty and the critical period.[141]

Yet, in the opinion of the less-than-gallant Burrows, sociopsychological forces were also at work:

The age of pleasing in all females is then past, though in many the desire to please is not the less lively. The exterior alone loses its attractions, but vanity preserves its pretensions. It is now especially that jealousy exerts its empire, and becomes very often a cause of delirium. Many, too, at this epoch imbibe very enthusiastic religious notions; but more have recourse to the stimulus of strong cordials to allay the uneasy and nervous sensations peculiar to this time of life, and thus produce a degree of excitation equally dangerous to the equanimity of the moral feelings and mental faculties.[142]

Double jeopardy surrounded the menopausal crisis.

Overall, Burrows judged hysteria intrinsic to the female sexual constitution: "Nervous susceptible women between puberty and thirty years of age, and clearly the single more so than the married, are most frequently visited by hysteria."[143] Its root, he emphasized, was organic: "Such constitutions have always a greater aptitude to strong mental emotions, which, on repetition, will superinduce mental derangement, or perhaps epilepsy."[144]

Unlike Enlightenment physicians, though prefiguring later Victorian opinion, Burrows feared hysteria, because it was always liable to flare into a dangerous, even incurable, condition. "Delirium is a common symptom of hysteria," he warned, "and this symptom is prolonged some-times beyond the removal of the spasm of paroxysm."[145] Thus, in the event of a repetition of hysterical fits, "the brain at length retained the morbid action, and insanity is developed." Indeed, because "hysteria is of that class of maladies which, wherever it is manifested, betrays a maniacal diathesis," it followed that "habitual hysteria clearly approximates to insanity."[146]

This prognosis (uterine disturbances lead to hysterical conditions that precipitate insanity proper) became standard to nineteenth-century medicine. "The reproductive organs . . . when unduly, unseasonably, or exorbitantly excited," argued Alfred Beaumont Maddock, are not only "necessarily subject to the usual advent of those physical diseases which are the inheritance of frail humanity, but are also closely interwoven with erratic and disordered intellectual, as well as moral, manifestations."[147] Such female disorders were, Maddock judged, the direct result of "the peculiar destiny that [woman] is intended by nature to fulfil, as

the future mother of the human race."[148] Others concurred. "Mental derangement frequently occurs in young females from Amenorrhoea," argued John Millar, "especially in those who have any strong hereditary predisposition to insanity."[149]