8—

The Prince's Parliament

Charles reached Portsmouth on October 5 and, despite rough weather, disembarked immediately. He spent a short night at the house of Viscount Annand at Guildford and long before dawn was on his way. News of his arrival had reached the City at midnight and his first sight of London, after six months' absence, was a dull red glow in a northern sky from hundreds of bonfires lit in joy at his return. As he crossed the Thames by Lambeth Stairs at daybreak the fires were paling but the bells of London were pealing out their greeting. He partook of hurried refreshment at Buckingham's house in the Strand, briefly receiving members of the Privy Council meanwhile, and, refusing the inopportune request of the Spanish Ambassador for an audience, took carriage with Buckingham for Royston where his father waited. But such a concourse of people had collected during his brief stop that his carriage could barely proceed up the Strand. It appeared to be 'carried on men's shoulders, and, as he passed, acclamations and blessings resounded from every side'. In the general rejoicing shops remained shut and work was at a standstill, wine was dispensed freely and tables set up in the streets for general feasting. A cartload of condemned criminals who crossed his path on their unhappy way to Tyburn were reprieved at Charles's own command. As evening fell the bonfires were rekindled, anything that would burn serving as fuel. 'The very vintners burnt their bushes in Fleet Street and other places, and their wine was burnt all over London and Westminster into all colours of the rainbow', while the cross in St Paul's churchyard was festooned with as many burning links as the Prince had years. The dull, wet weather made little difference. One hundred and eight bonfires were counted that night between St Paul's and London Bridge alone, and as light departed every window had its candle to illuminate the scene. But Charles and Buckingham had pressed on, pausing only to change coaches at Ware.

At Royston James came down from his room to welcome them. As they met on the stairs the Prince and the Duke fell on their knees before the old King and they all wept. Nothing more was seen by the courtiers as the three passed into the privacy of James's room. Apart from Charles's boast, 'I am ready to conquer Spain, if you will allow me to do it!', no details of that first meeting were allowed to penetrate the outer world. Low voices, occasional more emphatic tones and frequent bursts of laughter were all that could be heard. When at last they emerged James was saying that he liked not to marry his son with a portion of his daughter's tears — a remark which, in varying form, would be heard frequently in the following weeks. Once more the emphasis had changed. Little had been heard of the Palatinate during the marriage negotiations. Now that these had failed the three men made a virtue of necessity, attributing the breakdown to Spain's attitude to the German war.

The staging of the reunion at Royston was sound, for the place was distant from London, the roads wretched and the accommodation limited. The weather also helped to keep people away, and for a couple of weeks the three men were able to preserve their privacy, Secretary Conway probably being the only person in their full confidence. Meanwhile nothing could stem the continued rejoicing at the Prince's arrival without the Infanta. At Cambridge every college had a speech and an extra dish for supper, while at St Paul's a solemn service gave thanks for his safe return.[1]

Charles himself had little inclination to celebrate. Letters from Bristol informed him that the Infanta had no intention of going into a convent and could not be forced because after marriage she would be 'her own woman'; she seemed, indeed, the Ambassador reported, more loving towards the Prince than she had been while he was in Spain, she continued her English lessons, was called the Princess of England still, and was weary of the junta and all its restrictions. The Pope's dispensation was expected daily. A misunderstanding had already put Bristol in possession of Charles's cancellation of his proxy but in the circumstances Bristol decided to ignore it until he had heard further from England. Charles now panicked at the thought of being married by proxy to the Princess who, a few weeks earlier, he had so ardently desired. James once more brought in the restoration of the Palatinate as a condition of the marriage while Charles rushed off a series of urgent notes to Bristol: 'Make what shifts or fair excses you will, but I command you, as you answer it upon your peril, not to

deliver my proxy'; 'Whatever answer ye get, ye must not deliver the proxy till ye make my father and me judge of it.' But the Pope's approval of the marriage was delivered to King Philip in Madrid on November 19 while the courtiers bringing these despatches were still pounding their way across Europe. Bristol had only his own reading of the situation to guide him. In accordance with the proxy agreement the date of the wedding was fixed for November 29 and he and Aston ordered clothes for themselves and thirty rich liveries for their attendants. The Spanish erected a tapestry-covered terrace between the royal palace and the church, and invitations were sent out both for the wedding and for the christening of a baby Spanish princess, which was to take place on the same day. Then with preparations at their height, there arrived on the 25th, four days before the ceremonies, the four emissaries from England countermanding the proxy. If Charles's object had been the humiliation of Spain, he could not have succeeded better. The decorations were taken down, the Infanta's English lessons ceased, she was once more the Infanta of Spain and ceased to be the Princess of England.[2]

When he instructed Bristol to withhold his proxy Charles may not have envisaged a situation which worked out with quite so much public humiliation to the Infanta and her family. He did write to her, but his letters were returned unopened. He was then convinced that the Spanish Court had been deceiving him from the beginning and that she was as guilty as anyone else. This was particularly humiliating to a Prince who had wooed as ardently, and as publicly, as Charles. It was, moreover, virtually his first love affair and in the bitterness of his own rejection he had little thought for the feelings of the lady. It was left for the English Ambassador Extraordinary to make the only human comment. The lapse of the proxy, wrote Bristol, would not only put 'great scorn' upon the Spanish King but would be a 'great dishonour' for the Infanta. And, he added, 'whosoever else may have deserved it, she certainly hath not deserved disrespect nor discomfort'. Though her attitude and her feelings remain as remote as those of her family and friends, she was, perhaps, the greatest sufferer in the whole unhappy episode. But her marriage in 1631 to her cousin Ferdinand, the Emperor's son, was more than ordinarily happy. In due course she became Queen of Bohemia and Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, in strange contrast to Charles's sister, the exiled Queen of Bohemia, whose cause had been the origin of Charles's wooing. Maria died in 1646 in childbed of her fourth child with

knowledge of the deep strife that wracked the country which might have been her own: whether events would have moved differently if she had been Queen of England neither she nor Charles could conjecture.

The close conference of the three men at Royston and the posting of couriers to and from Spain had occasioned the utmost speculation, and by the middle of October loyalty and curiosity could no longer be restrained, even by the state of the roads and the execrable weather, and everyone was flocking out to Royston to pay their respects. James and his son moved another thirty miles to Hinchinbrook and enjoyed some hunting. They moved next to Newmarket. Then, at the end of the month, with James suffering from undefined pains which made movement difficult, Charles posted to London with Buckingham and at a brief meeting of the Privy Council gave a short account of the Spanish business. As always, physically tireless, rising early and travelling hard in bitter weather, he merely gave himself time to relax in his own palace of St James's on November 1 to see the King's Company perform The Mayd of the Mill by Beaumont and Fletcher, and then posted back to Newmarket.

He was in London again on the 5th where, as part of the anniversary observance of the Gunpowder Plot, he saw the Cockpit Company at Whitehall perform The Gipseys by Middleton and Rowley. On the 9th he received the Spanish Ambassadors, doing so 'with . . . no more capping nor courtesie then must needs, a lesson belike he learned in Spaine', as Chamberlain noted. In this, and in the way he disposed ostentatiously to his servants of presents he had received from the Spaniards, he set the general tone. Archie, the jester, fooled around in a suit given him by the Condé d'Olivarez, the tongues of courtiers who had been in Spain were loosed, and stories of ill-usage, scant food, discourtesies, bigotry, as well as of the general poverty of the country outside the capital, were soon circulating. There was even talk of the Spaniard's design on Charles — it was a marvel he got away so easily — he had only his sister to thank for that, her succession being infinitely more to be feared by the Spaniards than his own. To emphasize the difference between the two countries, as well as to celebrate their return, Buckingham gave a feast of 'superabundant plenty' on November 18 of which the centre piece consisted of twelve pheasants piled on one dish, forty dozen partridges, and forty dozen quail. James and Charles partook and the three of them attended a

masque by John Maynard, the main theme of which was congratulation to the Prince on his return.

In the general obsession with Spanish affairs the burning of Alderman Cockayne's house in Cheapside on November 15 created but a passing diversion, even though he lost £10,000 in goods and merchandise. He was a hard man, who had retained his own wealth in spite of the ruin of thousands of poor cloth workers through his unhappy project of dyeing cloth, and there was little interest and no pity to spare for him. More serious were the smallpox and a contagious, spotted fever which were raging as the year drew to a close, claiming their victims by death and by the dreaded pock marks. In spite of so many unpropitious circumstances, attempts were made by the Court to enjoy Christmas and to rehearse the Twelfth Night masque as usual. Neptune's Triumph for the Return of Albion by Ben Jonson had to be postponed and finally abandoned on the excuse of the King's indisposition, but rumour had it that the French and Spanish Ambassadors would not attend together, and it was difficult to give precedence to either. Charles, continuing to evince his pleasure in the drama, attended all the Christmas plays, which included The Bondman by Massinger and Middleton's The Changeling .

James was still struggling to maintain his policy of friendship with Spain. Charles, on the other hand, could see no alternative but war to recover the Palatinate and bring Spain to her knees. Buckingham agreed with him. He was not only stung by the failure of what he expected to be his greatest triumph, he was humiliated by the knowledge that his charm had not succeeded against the gravitas of the Spanish nobility. His measure of pique and irritation overflowed when he learned that his name had not been inscribed upon the commemorative pillar erected at the Escurial. But one thing was certain. If there was to be war there must be money. And to obtain supplies it was necessary to call a Parliament.

James accepted the situation reluctantly and on December 28, sorely against his will, signed the warrant for the issue of writs for the new Parliament. The dilemma he was in possibly accounts for the fact that there is almost no evidence of James's direct intervention in the elections. Charles and Buckingham, on the other hand, exerted themselves to the utmost to obtain the return of pro-war and anti-Spanish members who would support them. It was Charles's first experience of attempting to 'manage' a Parliament and he made no bones about using his patronage and pressing his candidates wherever he could.

On his Cornish estates, for example, letters went out in his name recommending candidates for at least thirteen boroughs, though only five were returned, including Sir Richard Weston for Bossiney and Thomas Carey, son of Robert, for Helston. At Chichester in Sussex Sir Thomas Edmondes's success was probably due to the Prince's support; Sir Henry Vane, Charles's cofferer, was returned for Carlisle — without patronage though he was a known friend of the Prince. Francis Finch, Charles's nominee, was returned for Eye in Suffolk and Ralph Clare, of the Prince's Privy Chamber, for Bewdley — but he was also lord of the manor and was supported by local loyalty. On the Prince's Yorkshire estates another second generation Carey, Sir Henry, was returned on Charles's nomination for Beverley. But there were also distinct refusals. In Boroughbridge Sir Edmund Verney, supported by the Prince, was turned down in favour of Ferdinando Fairfax. In Plymouth and Coventry the Prince's nominees were passed over in favour of the City recorders, John Glanville and Sir Edward Coke, while Cottington was turned down three times, possibly because of his Catholic affiliations, before being returned for Camelford. Obviously, apart from direct intervention, there were friendships, connections, and general goodwill which secured the return of candidates favourable to Charles.

Buckingham had less territorial patronage to exercise, but his network of family connections and office dependencies was vast and he was able to ensure the return of members who would support his policy. So the Parliament of 1624, although by no means 'packed', was an assembly in which there was considerable support for Charles and Buckingham. But although it was likely to be anti-Spanish, it was not so certain that it would also be pro-war. Members came to Parliament with many interests to serve. On the whole they were hard-headed and kept their purse-strings tight. Charles begged his father to act with decision, to think of his sister and her children. Elizabeth herself was full of hope; 'my brother', she wrote to Sir Thomas Roe, 'doth show so much love to me in all things, as I cannot tell you how much I am glad of it.' She had particular hope from the Parliament for it began on their dear dead brother's birthday.

On that day, February 19, after two postponements because of plague, James opened what was to be his last Parliament with considerable pomp. He told the members how sadly he had been deceived by Spain, how he wanted peace but was forced to admit that the omens were otherwise. He asked their advice: 'I assure you ye may freely

advise me, seeing of my princely fidelity you are invited thereto.' This was an innovation, indeed, the King delivering to them, unsolicited, the right to discuss both foreign policy and, by implication, his son's marriage. He dealt briefly with the Spanish visit, explaining that Charles had gone to find out in the quickest way what the Spaniards intended. This was a good resolution, James asserted, clinching the matter with an aphorism: 'I had general hopes before, but Particulars will resolve matters, Generals will not'. The details of the Spanish journey, he told them, would be communicated by Buckingham supported by Charles. The Speaker, Sir Thomas Crew, indicated at once the anti-Papist feeling of the House by desiring the strict execution of the recusancy laws. On the question of the Palatinate he was cool: 'God, in His due Time, will restore the distraught Princess.'

On February 24, in the great hall of Whitehall Palace, where it was usual for kings to preside, Buckingham in robes of state held the centre of the stage while he gave his account to the Lords of the Spanish adventure, supported and supplemented by Charles. Three days later Weston, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, repeated the tale to the Commons. The detailed story made bitter hearing. The Duke was now at the height of his power and, next to the Prince, the most popular man in England. When the Spanish Ambassador complained that he had slandered the Spanish king Parliament promptly retaliated by declaring that Buckingham deserved commendation as good patriot and loyal minister. Even his former enemies now joined the anti-Spanish and pro-war group which he led. No wonder it was said 'that never before did meet in one man . . . so much love of the King, Prince and People. He sways more than ever for whereas he was before a favourite to the King, he is now a favourite to the Parliament, people, and city, for breaking the match with Spain'.[3]

Observers noted at the same time Charles's assumption of power, 'entering into command of affairs by reason of the King's absence and sickness, and all men address themselves unto him'. The 'brave Prince' never missed a day at the Parliament, he was frequently in the Council Chamber, he organized affairs tirelessly and with care, riding backwards and forwards between Royston or Newmarket and London, rebuking any who opposed him, keeping the reins firmly in his hands. He had grown a beard while in Spain, he was 'somewhat stouter' and the Spanish experience had matured him. One observer was so impressed by his bearing that he thought 'he had concealed himself before'. To some he seemed a little too popular. 'The Prince

his carriage at this Parliament', wrote the Earl of Kellie to the Earl of Mar in May, 'has been lytill too populare, and I dout his father was lytill of that mynd.' As a result there was 'not the harmonye betwyxt the Kings Majestie and the Prince' as could be wished.

A surprising development, considering his speech defect, was the frequency with which he spoke in Parliament; his slight stammer persisted, but it never deterred him, and he knew how to use his youth and his rank to the best advantage. On March 12, for example, he reported to the House of Lords on the findings of a committee which had met the previous day. In supplying money for war, he reported, 'it was fit to use Expedition, and so to provide, that we might not only shew our Teeth and do no more; but also be able to bite, when there should be Cause'. 'And', he added,

Gentlemen, I pray you think seriously of this Business: take it to Heart, and consider in it, First, my Father's Honour, Secondly mine, and more particularly mine, because it is my new entering into the world: If in this ye shall fail me, ye shall not only dishonour and discourage me, but bring Dishonour upon yourselves. But, if ye go with Courage, and shew Alacrity and Readiness in this Business, ye shall so oblige me unto you now, that I will never forget it hereafter; and, when Time doth serve, ye shall find your Loves and your Labours well bestowed.

The peroration was, perhaps, hardly adroit. But Charles had judged his audience well, and the immature words from the young Prince were strangely disarming. 'This Conclusion did so take us', wrote one who was present, 'That we all prayed God to bless him, as we had just Cause to honour him.' He was now, indeed, 'the glorious prince' of Conway's letter to Carleton, and the session began to be called 'the Prince's Parliament'.[4]

It was the considered policy of Charles and Buckingham to keep James away from Westminster, for they feared the influence of his basically pacific policy upon the basically parsimonious members. Conversely they wanted to keep away from James anyone who would encourage his lingering desire for peace with Spain. The two men whose influence they had most cause to fear were Lionel Cranfield, Earl of Middlesex, James's Lord Treasurer, and John Digby, Earl of Bristol, James's Ambassador Extraordinary in Madrid. Bristol they endeavoured to keep out of the country for as long as possible, Middlesex they turned upon immediately. Middlesex, James's most successful Treasurer, who 'had built up a surplus out of a deficit',

wanted the Spanish dowry as much as James himself did. He was shocked at the expenditure incurred by the Spanish journey and in Council he spoke against all warlike proposals from the point of view of one who has to find the money. On Charles's return from Madrid he was the only Privy Councillor to maintain that the Prince ought to continue with the Spanish marriage, whereupon Charles lost his temper and 'bade him judge of his merchandise, for he was no arbiter in points of honour'. But Middlesex could not be dismissed in this way. His success as Treasurer and his position close to James made him dangerous. Yet he was also vulnerable. In removing financial malpractices, in sweeping away graft and unnecessary expenditure, in his attitude to monopolies, Middlesex, like Bacon before him, had made enemies. Like Bacon, he had swum a little too near the edge in his own financial practices, and his own fortune was considerable. It was not difficult for his enemies to build up a case against him. It came to a head on 18 April 1624 in charges of bribery, extortion, oppression and 'other grievous misdemeanours', which were laid before the House of Lords by Sir Edward Coke and Sir Edwin Sandys, who used for the purpose the old practice of impeachment which had been used for Bacon's trial three years earlier.

James did what he could to save Middlesex but was hampered by the knowledge that Charles was deeply involved. It hardly needed Williams, his Lord Keeper, to write to him, 'your Son, the Prince, is the main Champion that encounters the Treasurer; whom, if you save, you foil your Son. For, though Matters are carried by the whole Vote of Parliament, and are driven on by the Duke, yet they that walk in Westminster Hall, call this the Prince's Undertaking.' In the absence of Buckingham through illness it was, indeed, Charles himself who led the attack upon Middlesex, disregarding his father's advice 'that he should not take part with a Faction in either House . . .' and should 'take heed, how he bandied to pluck down a Peer of the Realm by the Arm of the Lower House, for the Lords were the Hedge between himself and the People; and a Breach made in that Hedge, might in time perhaps lay himself open.'

James made a good speech in the defence of Middlesex. 'I were deceived, if he were not a good officer', he said. 'He was Instrument, under Buckingham, for the Reformation of the Household, the Navy, and the Exchequer.' 'All Treasurers', he asserted in one of his telling generalizations, 'if they do good service to their Master, must be generally hated.' He emphasized the point that, apart from Bacon's

impeachment, there was no precedent for informers being in the Lower House while the Judges were in the Upper House.

If the Accusations come in by the Parties wronged, then you have a fair Entrance for Justice; if by Men that search and hunt after other Men's Lives and Actions, beware of it; it is dangerous; it may be your own Case another Time. . . . Let no Man's particular ends bring forth a Precedent that may be prejudicial to you all, and your Heirs after you.

The question was not publicly asked — but was James thinking of any particular man's 'particular ends', and could that man have been Buckingham? In private he turned upon the Duke with the fury of a Hebrew prophet: 'By God, Steenie!', he exclaimed, 'you are a fool, and will shortly repent this folly!' while to Charles he burst out in anger that he would live to have his bellyfull of impeachments. 'When I am dead', he continued with even more prophetic insight, 'you will have too much cause to remember how much you have contributed to the weakening of the Crown by the two expedients you are now so fond of — war, and impeachment!'.

The sentence against Middlesex, delivered on May 13, was severe. He was to lose all his offices, to be incapable of holding any state office in future, to be fined £50,000, prohibited from taking his seat in Parliament or even coming within the verge of the Court, and to be imprisoned in the Tower during the King's pleasure. His prison sentence was remitted, his fine reduced, but he had been rendered powerless.[5]

On March 8 an Address of Both Houses had recommended that the treaty with Spain should be broken, and on March 20 the Commons voted three subsidies and three fifteenths (about £300,000) to be in the Exchequer within one year of the breaking of the treaty. The pill was sweetened and James had to swallow it. On March 22 he agreed to annul the Spanish treaty although it was not until April 6 that he permitted the departure of the courier carrying the information to Spain. Even then a separate letter to the English Ambassador at Madrid directed him to inform the Spanish King that, although James had listened to the advice of his Parliament, he was not bound to take it. But if James was slipping from his part of the bargain, Parliament put a bite in theirs by electing a Council of War, the first of its kind, to administer the taxes raised under Parliamentary supervision.

For the time being there was general agreement that the subsidy should be used for the repair of fortifications, for fitting out the fleet,

reinforcing troops in Ireland (England's 'back door'), and helping the Dutch Republic. Clashes with the Dutch in the East Indies, even the so-called massacre of Amboyna on February 11, seemed so little relevant to the European situation that in June England agreed to pay 2000 troops for two years to help the Dutch maintain their independence against Spain. Mansfeld came to London in April in an interval of the fighting. Charles made much of him; and the London populace, who fully approved his lodging in state in the apartments which had been prepared for the Infanta, gave him an enthusiastic welcome. On the 16th he went to Theobalds to see James who promised him 13,000 men and £20,000 a month if the French would do likewise. Charles was jubilant. Now, he declared, he had something worth writing to his sister about and she would hear tidings better and better every day!

Yet when Bristol arrived home on April 24 there was bound to be some anxiety. James had called him home on December 30, ostensibly as a reprimand, but it was possible that he hoped for the support of his pro-Spanish Ambassador against his Parliament. It took Bristol some time to assemble his own household goods, the possessions which Charles had left behind, and the jewels which the Spanish royal family had returned. He also had difficulty in raising funds for the journey, having lent profusely to Charles to pay for the Prince's farewell presents. In the end he pawned his plate, but it was not until March 17 that he left Madrid, the Spaniards expressing the utmost sorrow at his departure. He hardly realized the strength of the forces against him until he reached the French coast and found no vessel waiting to bear him home. Such delay was in keeping with the endeavours of Charles and Buckingham to keep him out of the country until Parliament had risen, for they feared nothing more than a fresh appraisal of the situation under Bristol's guidance. When he landed in England on April 24 he was put under house arrest and refused access to the King. Although Buckingham was ill, Charles pressed the case against the Ambassador with vindictiveness: 'I fear if you are not with us to helpe charge him', he wrote to the Duke, 'he may escape with too slight a charge.' Bristol was still under restraint when the Parliamentary session ended on May 29. The only reply to his reiterated demand for a hearing had been the appointment of a commission who presented him with a series of interrogatories which, in substance, were the charges made against him by Charles and Buckingham: that he had expected, even encouraged, the Prince to change his religion on his first coming to Spain; that he advised the Prince to stay longer in Spain

1

Charles shortly after coming to England, aged about four, by Robert Peake. The

haunted look of the sick child is in pathetic contrast to the richly embroidered robes.

2

Charles, Duke of York, aged probably eight or nine, showing the bright little face of

a happy and well-balanced child in good health. Artist unknown.

3

Charles at the age of ten or eleven proudly wearing the ribbon of the Garter. The fair

hair and skin are apparent in all these early portraits. From the miniature by Isaac Oliver.

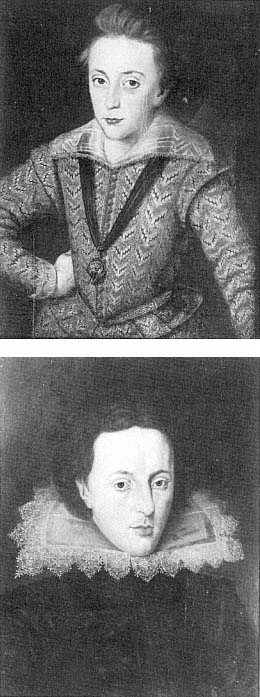

4, 5

Charles and his brother, shortly before Henry's death

in 1612. No. 4 is now generally identified as Henry

(Strong, English Icon ; Toynbee, Bodleian Library

Record , vol. 9, pt. 1, p. 22). The appearance of the sitter

still inclines me to the view of the 1952 Bodleian Picture

Book No. 6, since amended, that it is Charles.

than he should have done; that he had never insisted upon the restitution of the Palatinate to Frederick; that, overall, he was dilatory in getting a conclusion to the marriage treaty; and that, in the end, he did not obey the Prince's instructions concerning the proxy. In short, everything that had been misconceived, everything that had gone wrong, all the mistakes made by Charles himself, were laid on Bristol's shoulders.

The Earl's reply to the charges, which he reiterated in many letters to the King and to his friends, was always the same: on the matter of religion he had done no more than ask the Prince to make his position clear, he had been at one with James in hoping to receive from the match a worthy lady for Charles, a portion three times as large as had ever before been given, and the restitution of the Palatinate — for which, Bristol asserted, 'a daughter of Spain and two million had been no ill pawne'. He maintained that three months more would have decided the matter one way or another, yet he had been forced to see 'the whole state of affairs turned upside down' through no fault of his own. As for the proxy, he had acted as he thought proper, and in accordance with the Prince's honour, until he received a direct cancellation from England, when he withdrew it immediately.

The replies were straightforward, the Commission declared itself satisfied, the King was willing to see Bristol. Yet the Earl had hardly been tactful: he had questioned Charles's honour over the business of the proxy, he had implied that Charles had not been forthright in maintaining his religion, that Charles's decision to leave was taken at the wrong time and, overall, that it would have been better if the whole affair had been left in his hands. Yet such was Bristol's loyalty that he could hardly be touched. 'Whilst I thought the King desired the match I was for it against all the world', he wrote to Cottington. 'If his Majestye and the Prince will have a warr', he continued, 'I will spende my life and fortunes in it.' Buckingham and Charles suggested that if Bristol would retire to his country house all proceedings against him would be dropped. Bristol, with calm, exasperating integrity, continued to assert that if he had done anything wrong let his case be investigated, for he required only justification or death. House confinement continued, mainly on his manor of Sherborne, but he was not allowed at Court and he never saw James again.[6]

Parliament meantime coupled the Subsidy Act with a promise from James that no immunity for English Catholics would be included in any treaty for his son's marriage, and it called for an oath

from Charles, which he swore in Parliament on 5 April 1624, that 'whensoever it should please God to bestow upon him any lady that were Popish, she should have no further liberty but for her own family, and no advantage to recusants at home'. In calling for these assurances the Houses were not unmindful of rumours that another marriage treaty with another Catholic Princess was already under consideration. Perhaps they did not realize how far the considerations had already gone.