Grape Leafhopper

The grape leafhopper (Erythroneuraelegantuala ) (fig. 5) is the most common insect pest of grapes in the San Joaquin, Sacramento, and Napa valleys. Before the development of organic insecticides in the 1940s, severe damage occurred in some years, followed by periods of low populations. Now, with more effective pesticides, losses are primarily due to the cost of treatment plus the side effect of secondary outbreaks of other insect and spider mite pests resulting from the chemical treatment. A good example occurred in the 1960s when the leafhopper developed resistance to DDT and other chemicals. Growers began using the pesticide Sevin for leafhopper control. This material often caused severe outbreaks of spider mites, and in many cases the mites were more damaging to the grapes than the original leafhoppers.

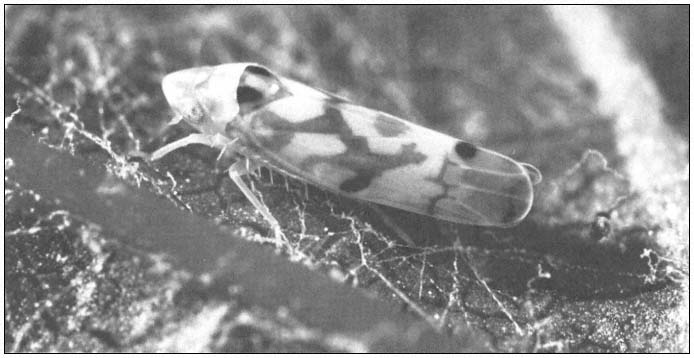

Figure 5.

Grape leafhopper (Erythroneura elegantuala ) is the most common and

most frequently treated grape pest in central and northern California.

Injury

Both adults and nymphs of the grape leafhopper have piercing mouth parts with which they puncture leaves and suck out the contents. Heavily damaged leaves lose their green color, dry up, and fall off the vine. In addition, in table grapes excessive fruit spotting from the leafhopper excrement can lead to unmarketable fruit before any effect on yield is noted. The crop is then sold for crushing, which is far less profitable than table grapes.

Natural Control

The important natural enemy of the grape leafhopper is a tiny, almost microscopic wasp Anagrusepos (fig. 6). This tiny wasp lays its eggs in the eggs of the grape leafhopper, resulting in the death of the leafhopper egg. These parasitic wasps are particularly valuable because of their amazing ability to locate and attack grape leafhopper eggs. Also, their short life cycle permits them to increase far more rapidly than can leafhopper populations. Their nine to 10 generations during the grape season make them capable of parasitizing 90–95% of all leafhopper eggs that are laid after July (Jensen and Flaherty 1981).

Anagrusepos overwinters on wild blackberries (Rubus spp.) on which it parasitizes the eggs of noneconomic, harmless leafhoppers (Dikrella spp.). These overwintering wasp populations tend to be along rivers that have an overstory of trees sheltering both wild grapes and wild blackberries. When the blackberries leaf out in February, the lush, new foliage apparently stimulates heavy oviposition by the Dikrella leafhoppers. The Anagrus populations increase enormously in these eggs, so that by late March and early April there is widespread dispersal of the newly produced Anagrus adult females. Fortunately, their dispersal occurs at the same time that grape leafhopper females begin to lay eggs. Vineyards located within an 8- to 16-km.

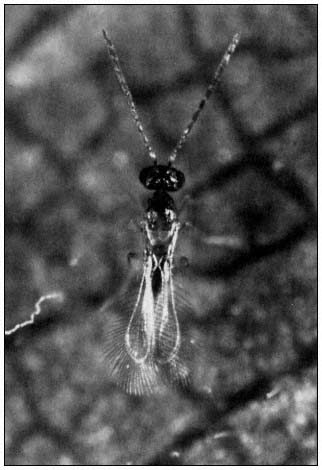

Figure 6.

Adult parasite (Anagrus epos ) of grape leafhopper eggs.

The male, shown above, is blackish-brown, while the

female is straw colored. This microscopic wasp often

reduces the grape leafhopper to nonpest status in

vineyards adjacent to riparian systems.

(5- to 10-mi.) range of an overwintering population will usually benefit immediately from the immigrant parasites. Vineyards distant from actual blackberry refuges may not show Anagrus activity until midsummer or later.

Efforts to establish blackberry refuges near vineyards in Tulare County have been only partially successful. This is attributed to the lack of a sheltering overstory of trees as would normally occur in riparian zones. In full sun, blackberry plantings gradually become dry thickets, with only surface foliage that becomes tough and leathery. Dikrella , wintertime host of Anagrusepos , is a shade- and moisture-loving insect that breeds on leaves inside blackberry vines were it is generally cooler and more humid. Old mature thickets, therefore, become less desirable Dikrella habitats and are, consequently, poor producers of Anagrus . A vineyard located within a natural dispersal area will, therefore, receive early important activity from the Anagrus parasites.

Where blackberries occur naturally, the commercial vineyards in the vicinity are not seriously troubled by grape leafhopper populations, and parasitism by Anagrus begins early in the season. This situation was first evident from studies in the Napa Valley, where blackberries are common, as well as in vineyards near the Stanislaus River, in the northern San Joaquin Valley. Certain locations along the Kings, Kaweah, and St. Johns rivers are also excellent sites for Anagrus where blackberries are common.

By contrast, the vineyards in the southern San Joaquin Valley are established in locations that are virtually reclaimed desert. They are miles from naturally occurring blackberries and chronically suffer from excessively high leafhopper populations. Parasitism by Anagrus does not occur until late in the summer, if at all.

Doutt and Nakata (1973) concluded that a vineyard situated within the predictable early dispersion range of Anagrus from overwintering sites can reasonably expect the parasite activity to be a substantial mortality factor on the first two broods of leafhoppers. This element is important in pest management programs of vineyards in the area, and any practice disruptive to this particular host/parasite system should be avoided.